Light is the chaser away of darkness. Shade is the obstruction of light.

[1]

[1]

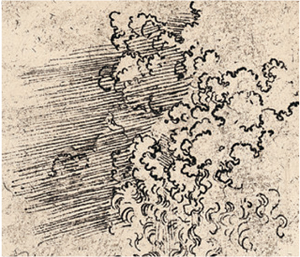

Shadow partakes of the nature of universal matter. All such matters are more powerful in their beginning and grow weaker towards the end, I say at the beginning, whatever their form or condition may be and whether their form or condition may be and whether visible or invisible. And it is not from small beginnings that they grow to a great size in time; as it might be a great oak which has a feeble beginning from a small acorn. Yet I may say that the oak is most powerful at its beginning; that is, where it springs from the earth, which is where it is largest.

Darkness, then, is the strongest degree of shadow and light is its least. Therefore, O Painter, make your shadow darkest close to the object that casts it, and make the end of it fading into light, seeming to have no end.

Shadow is the absence of light, merely the obstruction of the luminous rays by an opaque body. Shadow is of the nature of darkness. Light [on an object] is of the nature of a luminous body; one conceals and the other reveals. They are always associated and inseparable from all objects. But shadow is a more powerful agent than light, for it can impede and entirely deprive bodies of their light, while light can never entirely expel shadow from a body, that is, from an opaque body.

Every visible body is surrounded by light and shade.

An object represented in white and black will display stronger relief than in any other way; hence I would remind you, O Painter! To dress your figures in the lightest colors you can, since, if you put them in dark colors, they will be in too slight relief and inconspicuous from a distance. And the reason is that shadows of all objects are dark. And if you make a dress, there is little variety in the lights and shadows, while in light colors there are many grades.

[2]

If the sun is in the East and you look towards the West you will see every thing in full light and totally without shadow, because you see them from the same side as the sun.

And if you look towards the South or North you will see all objects in light and shade, because you see both the side towards the sun and the side away from it; and if you look towards the coming of the sun all objects will show you their shaded side, because on that side the sun cannot fall upon them.

The image of the sun will show itself brighter in the small waves than in the large ones. This happens because the reflections or images of the sun occur more frequently in the small waves than in the large ones, and the more numerous brightnesses give a greater light than the lesser number.

The waves that intersect after the manner of the scales of a fir cone reflect the image of the sun with the greatest splendor; and this occurs because there are as many images as there are ridges of the waves seen by the sun, and the shadows that intervene between these waves are small and not very dark; and the radiance of so many reflections is blended together in the image that proceeds from them to the eye, in such a way that these shadows are imperceptible.

[3]

[3]

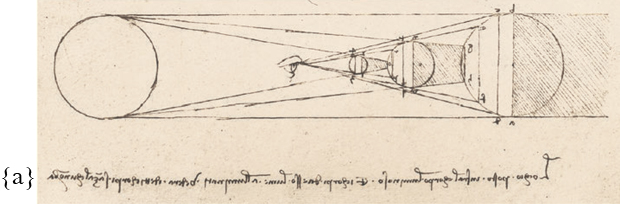

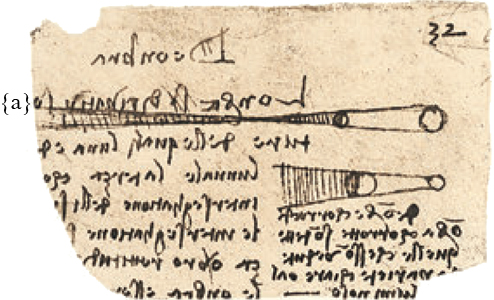

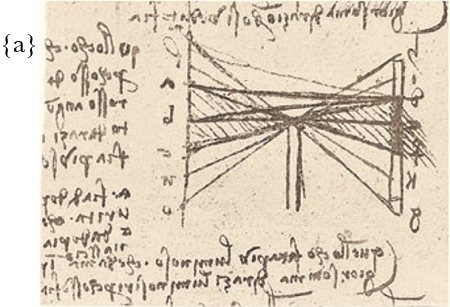

{a} When the eye is placed between the luminous body and the objects illuminated by it, these objects will be seen without any shadow.

The conditions of shadow and light [as seen] by the eye are three. Of these the first is when the eye and the light are on the same side of the object seen; the second is when the eye is in front of the object and the light is behind it. The third is when the eye is in front of the object and the light is on one side, in such a way as that a line drawn from the object to the eye and one from the object to the light should form a right angle where they meet.

If the eye, when [out of doors] in the luminous atmosphere, sees a place in shadow, this will look very much darker than it really is. This happens only because the eye when out in the air contracts the pupil in proportion as the atmosphere reflected in it is more luminous. And the more the pupil contracts, the less luminous do the objects appear that it sees. But as soon as the eye enters into a shady place the darkness of the shadow suddenly seems to diminish. This occurs because the greater the darkness into which the pupil goes, the more its size increases, and this increase makes the darkness seem less.

The eye that turns from a white object in the light of the sun and goes into a less fully lighted place will see everything as dark. And this happens either because the pupils of the eyes that have rested on this brilliantly lighted white object have contracted so much that, given at first a certain extent of surface, they will have lost more than 3/4 of their size; and, lacking in size, they are also deficient in [seeing] power.

Though you might say to me: A little bird [then] coming down would see comparatively little, and from the smallness of his pupils the white might seem black! To this I should reply that here we must have regard to the proportion of the mass of that portion of the brain that is given up to the sense of sight and to nothing else.

Or—to return—this pupil in Man dilates and contracts according to the brightness or darkness of [surrounding] objects; and since it takes some time to dilate and contract, it cannot see immediately on going out of the light and into the shade, nor, in the same way, out of the shade into the light, and this very thing has already deceived me in painting an eye, and from that I learnt it.

[4]

[4]

[4]

The first of the lights with which opaque bodies are illumined is called particular, and it is the sun or other light from a window or flame. The second is universal, as is seen in cloudy weather or in mist or the like. The third is the composite, that is, when the sun in the evening or the morning is entirely below the horizon.

Among bodies in varying degrees of darkness deprived of the same light, there will be the same proportion between their shadows as there is between their natural degrees of darkness, and you have to understand the same of their lights.

Primary light is that which falls on objects and causes light and shade. And derived lights are those portions of a body which are illuminated by the primary light.

The lights that may illuminate opaque bodies are of four kinds. These are: diffused light as that of the atmosphere, within our horizon. And direct, as that of the sun, or of a window or door or other opening. The third is reflected light; and there is a fourth which is that which passes through [semi] transparent bodies, as linen or paper or the like, but not transparent like glass, or crystal, or other diaphanous bodies, which produce the same effect as though nothing intervened between the shaded object and the light that falls upon it.

[5]

[5]

That portion of a body in light and shade will be least luminous which is seen under the least amount of light. That part of the object which is marked m is in the highest light because it faces the window a d by the line a f; n is in the second grade because the light b d strikes it by the line b e; o is in the third grade, as the light falls on it from c d by the line c h; p is the lowest light but one as c d falls on it by the line d v; q is the deepest shadow for no light falls on it from any part of the window.

{a} In proportion as c d goes into a d so will n r s be darker than m, and all the rest is space without shadow.

That portion of an illuminated object which is nearest to the source of light will be the most strongly illuminated. Every perfectly round body, when surrounded by light and shade, will seem to have one of its sides greater than the other, in proportion as the one is more lighted than the other.

That place will be most luminous from which the greatest number of luminous rays are reflected.

[6]

[6]

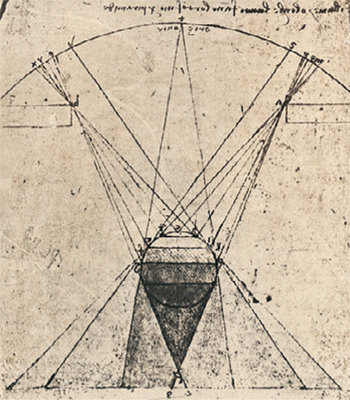

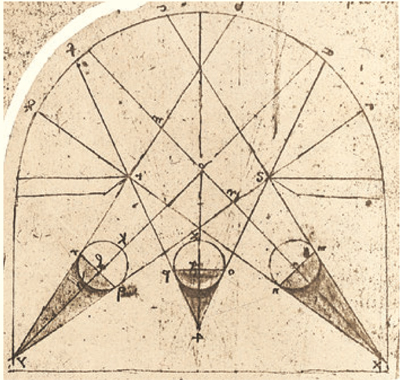

{a} The Proof and Reason Why among the Illuminated Parts Certain Portions Are in Higher Light than Others:

{b} [This] shows how light from any side converges to one point.

{c} Although the balls a b c are lighted from one window, nevertheless, if you follow the lines of their shadows you will see they intersect at a point forming the angle n.

{d} Since it is proved that every definite light is, or seems to be, derived from one single point, the side illuminated by it will have its highest light on the portion where the line of radiance falls perpendicularly; as is shown above in the lines a g, and also in a h and in l a; and that portion of the illuminated side will be least luminous where the line of incidence strikes it between two more dissimilar angles, as is seen at b c d. And by this means you may also know which parts are deprived of light, as is seen at m k.

{e} I will make further mention of the reason of reflections.

{f} Where the angles made by the lines of incidence are most equal there will be the highest light, and where they are most unequal it will be darkest.

[7]

[7]

The light which falls on a shaded body at the acutest angle receives the highest light, and the darkest portion is that which receives it at an obtuse angle and both the light and the shadow form pyramids. The angle c receives the highest grade of light because it is directly in front of the window a b and the whole horizon of the sky m x. The angle a differs but little from c because the angles which divide it are not so unequal as those below, and only that portion of the horizon is intercepted which lies between y and x. Although it gains as much on the other side, its line is nevertheless not very strong because one angle is smaller than its fellow.

The angles e i will have less light because they do not see much of the light m s and the light v x and their angles are very unequal. The angle k and the angle f are each placed between very unequal angles and therefore have but little light, because at k it has only the light p t, and at f only t q; o g is the lowest grade of light because this part has no light at all from the sky; and thence come the lines which will reconstruct a pyramid that is, the counterpart of the pyramid c; and this pyramid l is in the first grade of shadow; for this too is placed between equal angles directly opposite to each other on either side of a straight line that passes through the center of the body and goes to the center of the light.

The several luminous images cast within the frame of the window at the points a and b make a light that surrounds the derived shadow cast by the solid body at the points 4 and 6. The shaded images increase from o g and end at 7 and 8.

[8]

[8]

{a} All bodies, in proportion as they are nearer to, or farther from, the source of light, will produce longer or shorter derived shadows.

{b} Among bodies of equal size, that one which is illuminated by the largest light will have the shortest shadow.

Experiment confirms this proposition. Thus the body m n is surrounded by a larger amount of light than the body p q, as is shown above. Let us say that v c a b d x is the sky, the source of light, and that s t is a window by which the luminous rays enter, and so m n and p q are bodies in light and shade as exposed to this light.

[The body] m n will have a small derived shadow, because its original shadow will be small and the derivative light will be large, again, because the original light c d will be large and p q will have more derived shadow, because its original shadow will be larger, and its derived light will be smaller than that of the body m n because that portion of the hemisphere a b which illuminates it is smaller than the hemisphere c d which illuminates the body m n.

When there are several bodies of equal size which are equally distant from the eye, that will appear the smaller which is against a more luminous background.

[9]

[9]

You will note in drawing how among shadows some are indistinguishable in gradation and form; and these spherical surfaces have as many different degrees of light and shadow as there are varieties of brightness and darkness reflected from the objects round them.

That part of an opaque body will be more in shadow or more in light which is nearer to the dark body that shades it, or to the luminous body that gives it light.

The surface of every opaque body partakes of the color of its object, but the impression is greater or less in proportion as this object is nearer or more remote, and of greater or less power.

Objects seen between light and shadow will appear in greater relief than those that are in the light or in the shadow.

The smaller the light that falls upon an object the more shadow it will display. And the light will illuminate a smaller portion of the object in proportion as it is nearer to it; and conversely, a larger extent of it in proportion as it is farther off.

A light that is smaller than the object on which it falls will light up a smaller extent of it in proportion as it is nearer to it, and the converse, as it is farther from it. But when the light is larger than the object illuminated it will light a larger extent of the object in proportion as it is nearer and the converse when they are farther apart.

Darkness is the absence of light.

Shadow is the diminution of light.

A primary shadow is that which is attached to shaded bodies; it is that side of a body on which the light cannot fall.

Derived shadow is that which separates itself from shaded bodies and travels through the air.

Repercussed shadow is that which is surrounded by an illuminated surface.

The simple shadow is that which does not see any part of the light that causes it.

The simple shadow commences in the line that parts it from the boundaries of the luminous bodies.

[10]

[10]

It seems to me that the shadows are of supreme importance in perspective, seeing that without them opaque and solid bodies will be indistinct, both as to what lies within their boundaries and also as to their boundaries themselves, unless these are seen against a background differing in color from that of the substance; and consequently I say in this connection that every opaque body is surrounded and has its surface clothed with shadows and light. Moreover these shadows are in themselves of varying degrees of darkness, because they have been abandoned by a varying quantity of luminous rays; and these I call primary shadows, because they are the first shadows and so form a covering to the bodies to which they attach themselves.

From these primary shadows there issue certain dark rays, which are diffused throughout the air and vary in intensity according to the varieties of the primary shadows from which they are derived; and consequently I call these shadows derived shadows, because they have their origin in other shadow.

Moreover these derived shadows in striking upon anything create as many diVerent, effects as are the different places where they strike. And since where the derived shadow strikes, it is always surrounded by the striking of the luminous rays, it leaps back with these in a reflex stream towards its source and meets the primary shadow, and mingles with and becomes changed into it altering thereby somewhat of its nature.

Shadow is the diminution of light by the intervention of an opaque body. Shadow is the counterpart of the luminous rays which are cut off by an opaque body.

This is proved because the shadow cast is the same in shape and size as the luminous rays were that are transformed into a shadow.

[11]

[11]

Every shaded body that is larger than the pupil and that interposes between the luminous body and the eye will be seen dark.

That place is most shaded on which the greatest number of shaded rays converge.

That place which is smitten by the shaded rays at the greatest angle is darkest.

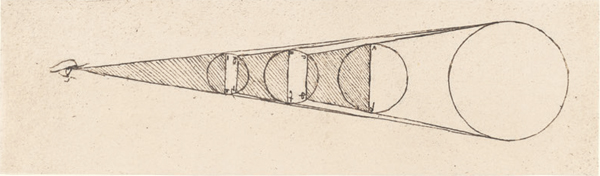

The simple derived shadows are of two kinds, that is to say, one finite in length and two infinite. The finite is pyramidal, and of those that are infinite one is columnar and the other expanding. And all three have straight sides, but the convergent, that is, the pyramidal shadow, proceeds from a shaded body that is less than the luminous body, the columnar proceeds from a shaded body equal to the luminous body, and the expanding from a shaded body greater than the luminous body.

[12]

[12]

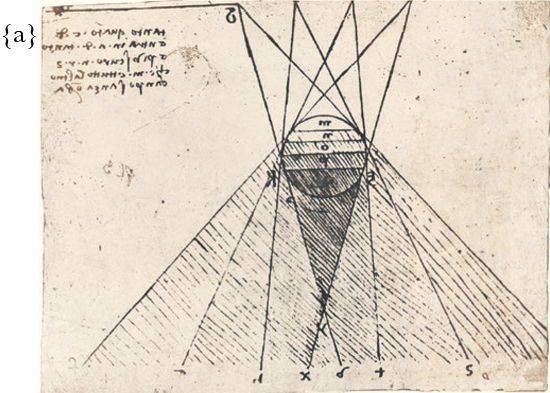

Of shadow:

{a} Derived shadows are of three kinds of which one is spreading, the second columnar, the third converging to the point where the two sides meet and intersect, and beyond this intersection the sides are infinitely prolonged or straight lines.

[13]

[13]

{a} The greatest depth of shadow is in the simple derived shadow, because it is not lighted by either of the two lights a b, c d.

{b} The next less deep shadow is the derived shadow e f n; and in this the shadow is less by half, because it is illuminated by a single light, that is c d.

{c} This is uniform in natural tone because it is lighted throughout by one only of the two luminous bodies. But it varies with the conditions of shadow, inasmuch as the farther it is away from the light the less it is illuminated by it.

{d} The third degree of depth is the middle shadow. But this is not uniform in natural tone; because the nearer it gets to the simple derived shadow the deeper it is, and it is the uniformly gradual diminution by increase of distance which is what modified it: that is to say, the depth of a shadow increases in proportion to the distance from the two lights.

The fourth is the shadow k r s and this is all the darker in natural tone in proportion as it is nearer to k s, because it gets less of the light a b, but by the accident [of distance] it is rendered less deep, because it is nearer to the light c d, and thus is always exposed to both lights.

The fifth is less deep in shadow than either of the others because it is always entirely exposed to one of the lights and to the whole or part of the other; and it is less deep in proportion as it is nearer to the two lights, and in proportion as it is turned towards the outer side x t; because it is more exposed to the second light a b. {e}

[14]

[14]

The forms of shadows are three: for if the substance that casts the shadow is equal in size to the light, the shadow is like a column which has no end; if the substance is greater than the light, its shadow is like a pyramid that grows larger as it recedes and of which the length has no end; but if the substance is smaller than the light, the shadow resembles a pyramid and comes to an end, as is seen in the eclipses of the moon.

A shaded body will appear of less size when it is surrounded by a very luminous background, and a luminous body will show itself greater when it is set against a darker background: as is shown in the heights of buildings at night when there are flashes of lightning behind them. For it instantly appears, as the lightning flashes, that the building loses a part of its height.

And from this it comes to pass that these buildings appear larger when there is mist, or by night, than when the air is clear and illumined.

[15]

{a} A luminous body that is long and narrow in shape gives more confused outlines to the derived shadow than a spherical light, and this contradicts the proposition next following: A shadow will have its outlines more clearly defined in proportion as it is nearer to the primary shadow or, I should say, the body casting the shadow; the cause of this is the elongated form of the luminous body a c, etc.

[16]

[16]

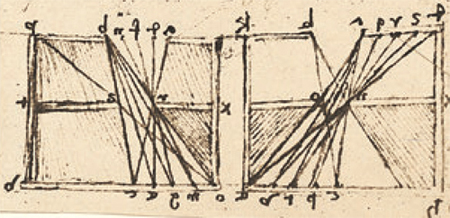

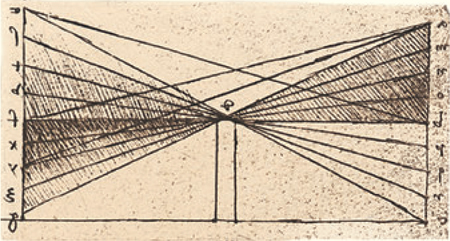

The surroundings in shadow mingle their derived shadow with the light derived from the luminous body. The derived shadow of the dark walls on each side of the bright light of the window are what mingle their various degrees of shade with the light derived from the window; and these various depths of shade modify every portion of the light, except where it is strongest, at c.

To prove this, let d a be the primary shadow that is turned toward the point e, and darkens it by its derived shadow; as may be seen by the triangle a e d, in which the angle e faces the darkened base d a e; the point v faces the dark shadow a s, which is part of a d, and as the whole is greater than a part, e, which faces the whole base [of the triangle], will be in deeper shadow than v, which only faces part of it.

In consequence, t will be less darkened than v, because the base of the [triangle] t is part of the base of the [triangle] v; and in the same way it follows that p is less in shadow than t, because the base of the [triangle] p is part of the base of the [triangle] t. And c is the terminal point of the derived shadow and the chief beginning of the highest light.

[17]

[17]

Among the shadows cast by bodies of equal mass but at unequal distances from the opening by which they are illuminated, that shadow will be the longest of the body which is least in the light. And in proportion as one body is better illuminated than another, its shadow will be shorter than another. The proportion n m and e v k bear to r t and v x corresponds with that of the shadow x to 4 and y.

The reason why those bodies which are placed most in front of the middle of the window throw shorter shadows than those obliquely situated is that the window appears in its proper form and to the obliquely placed ones it appears foreshortened; to those in the middle, the window shows its full size, to the oblique ones it appears smaller; the one in the middle faces the whole hemisphere that is e f and those on the side have only a strip; that is, q r faces a b; and m n faces c d; the body in the middle having a larger quantity of light than those at the sides is lighted from a point much below its center, and thus the shadow is shorter.

[18]

[18]

A shadow is never seen as of uniform depth on the surface which intercepts it unless every portion of that surface is equidistant from the luminous body. The shadow will appear lighter or stronger as it is surrounded by a darker or a lighter background. The background will be in parts darker or lighter, in proportion as it is farther from or nearer to the luminous body. Of various spots equally distant from the luminous body, those will always be in the highest light on which the rays fall at the smallest angles: The outline of the shadow as it falls on inequalities in the surface will be seen with all the contours similar to those of the body that casts it, if the eye is placed just where the center of the light was.

The shadow will look darkest where it is farthest from the body that casts it.

[19]

[19]

Although the breadth and length of lights and shadow will be narrower and shorter in foreshortening, the quality and quantity of the light and shade is neither increased nor diminished.

The function of shade and light, when diminished by foreshortening, will be to give shadow and to illuminate an object opposite, according to the quality and quantity in which they fall on the body.

In proportion as a derived shadow is nearer to its penultimate extremities the deeper it will appear. g z beyond the intersection faces only the part of the shadow [marked] y z; this by intersection takes the shadow from m n, but by direct line it takes the shadow a m hence it is twice as deep as g z. y x, by intersection takes the shadow n o, but by direct line the shadow n m a, therefore x y is three times as dark as z g; x f, by intersection faces o b and by direct line o n m a, therefore we must say that the shadow between f x will be four times as dark as the shadow z g, because it faces four times as much shadow.

Let a b be the side where the primary shadow is, and b c the primary light, d will be the spot where it is intercepted, f g the derived shadow and f e the derived light.

[20]

[20]

{a} A spot is most in the shade when a large number of darkened rays fall upon it. The spot that receives the rays at the widest angle and by darkened rays at the widest angle will be most in the dark; a will be twice as dark as b, because it originates from twice as large a base at an equal distance. A spot is most illuminated when a large number of luminous rays fall upon it. d is the beginning of the shadow d f, and tinges c but a little; d e is half of the shadow d f and gives a deeper tone where it is cast at b than at f. And the whole shaded space e gives its tone to the spot a.

[21]

[21]

That part of the surface of a body on which the images from other bodies placed opposite fall at the largest angle will assume their hue most strongly. In this diagram, 8 is a larger angle than 4, since its base a n is larger than e n, the base of 4. This diagram below should end at a n 4 8.

That portion of the illuminated surface on which a shadow is cast will be brightest which lies contiguous to the cast shadow. Just as an object that is lighted up by a greater quantity of luminous rays becomes brighter, so one on which a greater quantity of shadow falls, will be darker.

The distribution of shadow, originating in, and limited by, plane surfaces placed near to each other, equal in tone and directly opposite, will be darker at the ends than at the beginning, which will be determined by the incidence of the luminous rays.