Why does the eye see a thing more clearly in dreams than the imagination when awake?

[1]

[1]

And the mountains will seem few in number, for only those will be seen that are farthest apart from each other, since at such distances the increases in the density creates a brightness so pervading that the darkness of the hills is divided, and quite disappears towards their summits. In the small adjacent hills it cannot find such foothold, and therefore they are less visible and least of all at their bases.

Those who are in love with practice without knowledge are like the sailor who gets into a ship without rudder or compass and who never can be certain whither he is going. Practice must always be founded on sound theory, and to this, perspective is the guide and the gateway; and without this nothing can be done well in the matter of drawing.

Perspective is the best guide to the art of painting.

Perspective is of such a nature that it makes what is flat appear in relief, and what is in relief appear flat.

The perspective by means of which a thing is represented will be better understood when it is seen from the view point at which it was drawn.

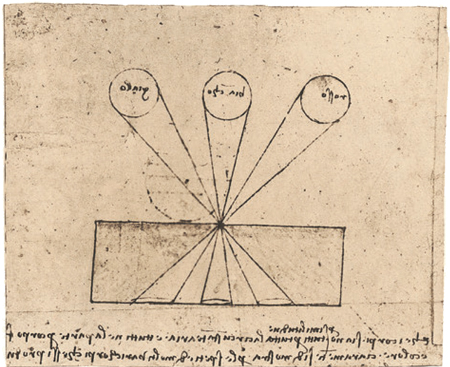

Perspective is nothing else than the seeing of an object behind a sheet of glass, smooth and quite transparent, on the surface of which all the things may be marked that are behind this glass; these things approach the point of the eye in pyramids, and these pyramids are cut by the said glass.

Perspective is a rational demonstration whereby experience confirms how all things transmit their images to the eye by pyramidal lines. By pyramidal lines I mean those that start from the extremities of the surface of bodies, and by gradually converging from a distance arrive at the same point; the said point being, as I shall show, in this particular case located in the eye, which is the universal judge of all objects. I call a point that which cannot be divided up into any parts; and as this point, which is situated in the eye is indivisible, no body can be seen by the eye that is not greater than this point, and this being the case it is necessary that the lines which extend from the object to the point should be pyramidal.

All the cases of perspective are expressed by means of the five mathematical terms, to wit: point, line, angle, surface, and body.

Of these the point is unique of its kind, and this point has neither height nor breadth, nor length nor depth, wherefore we conclude that it is indivisible and does not occupy space.

A line is of three kinds, namely straight, curved, and bent, and it has neither breadth, height nor depth, consequently it is indivisible except in its length; its ends are two points.

An angle is the ending of two lines in a point, and they are of three kinds, namely right angles, acute angles, and obtuse angles.

Surface is the name given to that which is the boundary of bodies, and it is without depth, and in such depth as it has it is indivisible as is the line or point, being divided only in respect of length or breadth. There are as many different kinds of surfaces as there are bodies that create them.

Body is that which has height, breadth, length, and depth, and in all these attributes it is divisible. These bodies are of infinite and varied forms.

If you wish to represent a thing near, which should produce the effect of natural things, it is impossible for your perspective not to appear false, by reason of all the illusory appearances and errors in proportion of which the existence may be assumed in a mediocre work, unless whoever is looking at this perspective finds himself surveying it from the exact distance, elevation, angle of vision or point at which you were situated to make this perspective.

Therefore it would be necessary to make a window of the size of your face or in truth a hole through which you would look at the said work. And if you should do this, then without any doubt your work will produce the effect of nature if the light and shade are correctly rendered, and you will hardly be able to convince yourself that these things are painted. Otherwise do not trouble yourself about representing anything, unless you take your view point at a distance of at least twenty times the maximum width and height of the thing that you represent; and this will satisfy every beholder who places himself in front of the work at any angle whatever.

There are three branches of perspective; the first deals with the reasons of the [apparent] diminution of the volume of opaque bodies as they recede from the eye, and is known as Diminishing or Linear Perspective.

The second contains the way in which colors vary as they recede from the eye. The third and last is concerned with how the outlines of objects [in a picture] ought to be less finished in proportion as they are remote.

Among objects of equal size, that which is most remote from the eye will look the smallest.

The thing that is nearer to the eye always appears larger than another of the same size that is more remote.

Small objects close at hand and large ones at a distance, being seen within equal angles, will appear of the same size.

There is no object so large but that at a great distance from the eye it does not appear smaller than a smaller object near.

A second object as far distant from the first as the first is from the eye will appear half the size of the first, though they be of the same size really.

Equal things equally distant from the eye will be judged by the eye to be of equal size. Equal things through being at different distances from the eye come to appear of unequal size. Unequal things by reason of their different distances from the eye may appear equal.

Among opaque bodies of equal magnitude, the diminution apparent in their size will vary according to their distance from the eye that sees them; but it will be in inverse proportion, for at the greater distance the opaque body appears less, and at a less distance this body will appear greater, and on this is founded linear perspective. And show secondly how every object at a great distance loses first that portion of itself which is the thinnest.

Thus with a horse, it would lose the legs sooner than the head because the legs are thinner than the head, and it would lose the neck before the trunk for the same reason. It follows therefore that the part of the horse that the eye will be able last to discern will be the trunk, retaining still its oval form, but rather approximating to the shape of a cylinder. It will lose its thickness sooner than its length from the second conclusion aforesaid.

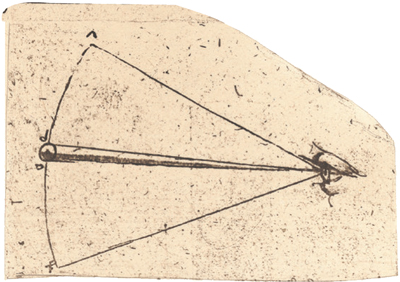

If the eye is immovable the perspective terminates its distance in a point; but if the eye moves in a straight line the perspective ends in a line, because it is proved that the line is produced by the movement of the point, and our sight is fixed upon the point. Consequently it follows that as the sight moves, the point moves, and as the point moves, the line is produced.

Of things of equal size situated at an equal distance from the eye, that will appear the larger which is whiter in color.

Of things which are the same in size and color that which is farther away will seem lighter and less in bulk.

Many things of great bulk lose their visibility in the far distance by reason of their color, and many small things in the far distance retain their visibility by reason of the said color.

An object of a color similar to that of the air retains its visibility at a moderate distance, and an object that is paler than the air retains it in the far distance, and an object which is darker than the air ceases to be visible at a short distance.

But of these three kinds of objects, that will be visible at the greatest distance of which the color presents the strongest contrast to itself.

[2]

[2]

In order to put into practice this perspective of the variation and loss or diminution of the essential character of colors, observe at every hundred braccia some standing in the landscape, such as trees, houses, men, and particular places.

Then in front of the first tree have a very steady plate of glass and keep your eye very steady, and then, on this plate of glass, draw a tree, tracing it over the form of that tree. Then move it on one side so far as that the real tree is close by the side of the tree you have drawn; then color your drawing in such a way as that in color and form the two may be alike, and that both, if you close one eye, seem to be painted on the glass and at the same distance.

Then, by the same method, represent a second tree, and a third, with a distance of a hundred braccia between each. And these will serve as a standard and guide whenever you work on your own pictures, wherever they may apply, and will enable you to give due distance in those works. But I have found that as a rule the second is 4/5 of the first when it is 20 braccia beyond it.

[3]

[3]

There is another kind of perspective which I call Aerial Perspective, because by the atmosphere we are able to distinguish the variations in distance of different buildings, which appear placed on a single line; as, for instance, when we see several buildings beyond a wall, all of which, as they appear above the top of the wall, look of the same size, while you wish to represent them in a picture as more remote one than another and to give the effect of a somewhat dense atmosphere. You know that in an atmosphere of equal density the remotest objects seen through it, as mountains, in consequence of the great quantity of atmosphere between your eye and them—appear blue and almost of the same hue as the atmosphere itself when the sun is in the East. Hence you must make the nearest building above the wall of its real color, but the more distant ones make less defined and bluer. Those you wish should look farthest away you must make proportionately bluer; thus, if one is to be five times as distant, make it five times bluer. And by this rule the buildings which above a [given] line appear of the, same size, will plainly be distinguished as to which are the more remote and which larger than the others.

Whenever a figure is placed at a considerable distance you lose first the distinctness of the smallest parts; while the larger parts are left to the last, losing all distinctness of detail and outline. What remains is an oval or spherical figure with confused edges.

That dimness that occurs by reason of distance, or at night, or when mist comes between the eye and the object, causes the boundaries of this object to become almost indistinguishable from the atmosphere.

When the sun rises and drives away the mists, and the hills begin to grow distinct on the side from which the mists are departing, they become blue and seem to put forth smoke in the direction of the mists that are flying away, and the buildings reveal their lights and shadows. Where the mist is less dense they show only their lights, and where it is denser nothing at all. Then it is that the movement of the mist causes it to pass horizontally and so its edges are scarcely perceptible against the blue of the atmosphere, and against the ground it will seem almost like dust rising.

Buildings that face the west only show their illuminated side, the rest the mist hides.

In proportion as the atmosphere is denser, the buildings in a city and the trees in landscapes will seem more infrequent, for only the most prominent and the largest will be visible.

If the true outlines of opaque bodies become indistinguishable at any short distance, they will be still more invisible at great distances. And since it is by the outlines that the true shape of each opaque body becomes known, whenever because of distance we lack the perception of the whole we shall lack yet more the perception of its parts and outlines.

I say that the reason that objects appear diminished in size is because they are remote from the eye; this being the case it is evident that there must be a great extent of atmosphere between the eye and the objects, and this air interferes with the distinctness of the forms of the object. Hence the minute details of these objects will be indistinguishable and unrecognizable.

Therefore, O Painter, make your smaller figures merely indicated and not highly finished, otherwise you will produce effects the opposite to nature, your supreme guide. The object is small by reason of the great distance between it and the eye, this great distance is filled with air, that mass of air forms a dense body which intervenes and prevents the eye seeing the minute details of objects.

Experience shows us that the air must have darkness beyond it and yet it appears blue. If you produce a small quantity of smoke from dry wood and the rays of the sun fall on this smoke, and if you then place behind the smoke a piece of black velvet on which the sun does not shine, you will see that all the smoke that is between the eye and the black stuff will appear of a beautiful blue color. And if instead of the velvet you place a white cloth, smoke that is too thick hinders, and too thin smoke does not produce, the perfection of this blue color. Hence a moderate amount of smoke produces the finest blue.

Water violently ejected in a fine spray and in a dark chamber where the sunbeams are admitted produces these blue rays and the more vividly if it is distilled water, and thin smoke looks blue. This I mention in order to show that the blueness of the atmosphere is caused by the darkness beyond it.

In the morning the mist is thicker up above than in the lower parts because the sun draws it upwards; so with high buildings the summit will be invisible although it is at the same distance as the base. And this is why the sky seems darker up above and towards the horizon, and does not approximate to blue, but is all the color of smoke and dust.

The atmosphere when impregnated with mist is altogether devoid of blueness and merely seems to be the color of the clouds, which turn white when it is fine weather. And the more you turn to the west the darker you will find it to be, and the brighter and clearer towards the east. And the verdure of the countryside will assume a bluish hue in the half mist, but will turn black when the mist is thicker.

I say that the blueness we see in the atmosphere is not intrinsic color, but is caused by warm vapor evaporated in minute and insensible atoms on which the solar rays fall, rendering them luminous against the infinite darkness of the fiery sphere that lies beyond and includes it. Hence it follows, as I say, that the atmosphere assumes this azure hue by reason of the particles of moisture which catch the rays of the sun.

Again, we may note the difference in particles of dust, or particles of smoke, in the sunbeams, admitted through holes into a dark chamber, when the former will look ash grey and the thin smoke will appear of the most beautiful blue. It may be seen again in the dark shadows of distant mountains when the air between the eye and those shadows will look very blue, though the brightest parts of those mountains will not differ much from their true colors.

But if anyone wishes for a final proof let him paint a board with various colors, among them an intense black; and over all let him lay a very thin and transparent [coating of] white. He will then see that this transparent white will nowhere show a more beautiful blue than over the black, but it must be very thin and finely ground.

Darkness steeps everything with its hue, and the more an object is divided from darkness the more it shows its true and natural color.

All colors, when placed in the shade, appear of an equal degree of darkness, among themselves. But all colors, when placed in a full light, never vary from their true and essential hue.

Since we see that the quality of color is known [only] by means of light, it is to be supposed that where there is most light the true character of a color in light will be best seen. Where there is most shadow the color will be affected by the tone of that [shadow]. Hence, O Painter! Remember to show the true quality of colors in bright lights.

Colors seen in shadow will display more or less of their natural brilliancy in proportion as they are in fainter or deeper shadow. But if these same colors are situated in a well-lighted place, they will appear brighter in proportion as the light is more brilliant.

Colors seen in shadow will display less variety in proportion as the shadows in which they lie are deeper. And evidence of this is to be had by looking from an open space into the doorways of dark and shadowy churches, where the pictures that are painted in various colors all look of uniform darkness.

Hence at a considerable distance all the shadows of different colors will appear of the same darkness. It is the light side of an object in light and shade that shows the true color.

Of various colors, none of which are blue, that which at a great distance will look bluest is the nearest to black; and so, conversely, the color that is least like black will at a great distance best preserve its own color.

Hence the green of fields will assume a bluer hue than yellow or white will, and conversely yellow or white will change less than green, and red still less.

Of several [patches of] color, all equally white, that [patch] will look whitest which is against the darkest background. And black will look most intense against the whitest background.

And red will look most vivid against the most yellow background; and the same is the case with all colors when surrounded by their strongest contrasts.

Every opaque and colorless body assumes the hue of the color reflected on it; as happens with a white wall.

The hue of an illuminated object is affected by that of the luminous body [that illuminates it].

The surface of every opaque body is affected by the [reflected] color of the objects surrounding it. But this effect will be strong or weak in proportion as those objects are more or less remote and more or less strongly [colored].

Every object devoid of color in itself is more or less tinged by the color [of the object] placed opposite. This may be seen by experience, inasmuch as any object that mirrors another assumes the color of the object mirrored in it. And if the surface thus partially colored is white, the portion that has a red reflection will appear red, or any other color, whether bright or dark.

A shadow is always affected by the color of the surface on which it is cast.

An image produced in a mirror is affected by the color of the mirror.

Every body that moves rapidly seems to color its path with the impression of its hue. The truth of this proposition is seen from experience; thus when the lightning moves among dark clouds the speed of its sinuous flight makes its whole course resemble a luminous snake. So in like manner if you wave a lighted brand its whole course will seem a ring of flame. This is because the organ of perception acts more rapidly than the judgment.

Just as a stone flung into the water becomes the center and cause of many circles, and as sound diffuses itself in circles in the air: so any object, placed in the luminous atmosphere, diffuses itself in circles, and fills the surrounding air with infinite images of itself. And is repeated, the whole everywhere, and the whole in every smallest part.

[4]

[4]

All bodies together, and each by itself, give off to the surrounding air an infinite number of images that are all-pervading and each complete. Each conveying the nature, color and form of the body that produces it.

{a} It can clearly be shown that all bodies are, by their images, all-pervading in the surrounding atmosphere, and each complete in itself as to substance, form, and color. This is seen by the images of the various bodies that are reproduced in one single perforation through which they transmit the objects by lines that intersect and cause reversed pyramids, from the objects, so that they are upside down on the dark plane where they are first reflected.

The air is filled with endless images of the objects distributed in it; and all are represented in all, and all in one, and all in each, whence it happens that if two mirrors are placed in such a manner as to face each other exactly, the first will be reflected in the second and the second takes to it the image of itself with all the images represented in it. Among which is the image of the second mirror, and so, image within image, they go on to infinity in such a manner as that each mirror has within it a mirror, each smaller than the last and one inside the other. Thus, by this example, it is clearly proved that every object sends its image to every spot whence the object itself can be seen; and the converse: that the same object may receive in itself all the images of the objects that are in front of it.

Hence the eye transmits through the atmosphere its own image to all the objects that are in front of it and receives them into itself, that is to say, on its surface, whence they are taken in by the common sense, which considers them and if they are pleasing commits them to the memory. Whence I am of the opinion that the invisible images in the eyes are produced towards the object, as the image of the object to the eye. That the images of the objects must be disseminated through the air.

An instance may be seen in several mirrors placed in a circle, which will reflect each other endlessly. When one has reached the other it is returned to the object that produced it, and thence—being diminished—it is returned again to the object and then comes back once more, and this happens endlessly.

If you put a light between two flat mirrors with a distance of one braccio between them you will see in each of them an infinite number of lights, one smaller than another, to the last. If at night you put a light between the walls of a room, all the parts of that wall will be tinted with the image of that light. And they will receive the light and the light will fall on them, mutually, that is to say, when there is no obstacle to interrupt the transmission of the images. The same example is seen in a greater degree in the distribution of the solar rays that all together, and each by itself, convey to the object the image of the body which causes it.

That each body by itself alone fills with its images the atmosphere around it, and that the same air is able, at the same time, to receive the images of the endless other objects that are in it—this is clearly proved by these examples. And every object is everywhere visible in the whole of the atmosphere, and the whole in every smallest part of it; and all the objects in the whole, and all in each smallest part; each in all and all in every part.

The image of the sun will be more brightly shown in small waves than in large ones—and this is because the reflections or images of the sun are more numerous in the small waves than in large ones, and the more numerous reflections of its radiance give a larger light than the fewer.

Waves that intersect like the scales of a fir cone reflect the image of the sun with the greatest splendor; and this is the case because the images are as many as the ridges of the waves on which the sun shines, and the shadows between these waves are small and not very dark; and the radiance of so many reflections together becomes united in the image that is transmitted to the eye, so that these shadows are imperceptible.

I say that sight is exercised by all animals, by the medium of light; and if any one adduces, as against this, the sight of nocturnal animals, I must say that this in the same way is subject to the very same natural laws.

For it will easily be understood that the senses which receive the images of things do not project from themselves any visual virtue. On the contrary the atmospheric medium that exists between the object and the sense incorporates in itself the figure of things, and by its contact with the sense transmits the object to it. If the object—whether by sound or by odor—presents its spiritual force to the ear or the nose, then light is not required and does not act. The forms of objects do not send their images into the air if they are not illuminated; and the eye being thus constituted cannot receive that from the air, which the air does not possess, although it touches its surface.

If you choose to say that there are many animals that prey at night, I answer that when the little light which suffices the nature of their eyes is wanting, they direct themselves by their strong sense of hearing and of smell, which are not impeded by the darkness, and in which they are very far superior to man. If you make a cat leap, by daylight, among a quantity of jars and crocks you will see them remain unbroken, but if you do the same at night, many will be broken. Night birds do not fly about unless the moon shines full or in part; rather do they feed between sundown and the total darkness of the night.

No body can be apprehended without light and shade, and light and shade are caused by light.

If the object in front of the eye sends its image to it, the eye also sends its image to the object, so of the object and of the image proceeding from it no portion is lost for any reason either in the eye or the object. Therefore we can sooner believe that it is the nature and power of this luminous atmosphere that attracts and takes into itself the images of the objects that are within it than that it is the nature of the objects which transmits their images through the atmosphere.

If the object in front of the eye were to send its image to it, the eye would have to do the same to the object, whence it would appear that these images were incorporeal powers. If it were thus it would be necessary that each object should rapidly become less; because each body appears as an image in the atmosphere in front of it, that is, the whole body in the whole atmosphere and the whole in the part, and all the bodies in the whole atmosphere and all in the part, referring to that portion of it which is capable of receiving into itself the direct and radiating lines of the images transmitted by the objects.

For this reason then it must be admitted that it is the nature of this atmosphere which finds itself among the objects to draw to itself, like a magnet, the images of the objects among which it is situated.

All things transmit their image to the eye by means of pyramids; the nearer to the eye these are intersected, the smaller the image of their cause will appear.

If you should ask how you can demonstrate these points to me from experience, I should tell you, as regards the vanishing point that moves with you, to notice as you go along by lands ploughed in straight furrows, the ends of which start from the path where you are walking, you will see that continually each pair of furrows seem to approach each other and to join at their ends.

As regards the point that comes to the eye, it may be comprehended with greater ease; for if you look in the eye of anyone you will see your own image there; consequently if you suppose two lines to start from your ears and proceed to the ears of the image that you see of yourself in the eye of the other person, you will clearly recognize that these lines contract so much that when they have continued only a little way beyond your image as mirrored in the said eye they will touch one another in a point.

Nature has made the surface of the pupil situated in the eye convex in form so that the surrounding objects may imprint their images at greater angles than could happen if the eye were flat.

The images of the objects placed before the eye pass to the vitreous sphere by the gate of the pupil, and they intersect within this pupil in such a way that the vitreous sphere is struck on its left side by the right ray of the right sphere, and it does the same on the opposite side; afterwards it penetrates this vitreous sphere, and the rays contract and find themselves much closer together when they are on the opposite side of this sphere than when they strike it in the beginning.

When both eyes direct the pyramid of sight to an object, that object becomes clearly seen and comprehended by the eyes.

[5]

[5]

All the images of objects reach the senses by a small aperture in the eye; hence, if the whole horizon a d is admitted through such an aperture, the object b c being but a very small fraction of this horizon, what space can it fill in that minute image of so vast a hemisphere? And because luminous bodies have more power in darkness than any others, it is evident that, as the chamber of the eye is very dark, as is the nature of all colored cavities, the images of distant objects are confused and lost in the great light of the sky; and if they are visible at all, appear dark and black, as every small body must when seen in the diffused light of the atmosphere.

We see quite plainly that all the images of visible objects that lie before us, whether large or small, reach our sense by the minute aperture of the eye. If, through so small a passage the image can pass of the vast extent of sky and earth, the face of a man—being by comparison with such large images almost nothing by reason of the distance that diminishes it—fills up so little of the eye that it is indistinguishable.

Having also to be transmitted from the surface to the sense through a dark medium, that is to say, the crystalline lens which looks dark; no other reason can in any way be assigned. If the point in the eye is black, it is because it is full of a transparent humor as clear as air and acts like a perforation in a board; on looking into it, it appears dark and the objects seen through the bright air and a dark [medium] one become confused in this darkness.

Every object we see will appear larger at midnight than at midday, and larger in the morning than at midday.

This happens because the pupil of the eye is much smaller at midday than at any other time.

In proportion as the eye or the pupil of the owl is larger in proportion to the animal than that of man, so much the more light can it see at night than man can; hence at midday it can see nothing if its pupil does not diminish; and, in the same way, at night things look larger to it than by day.

If the eye is required to look at an object placed too near to it, it cannot judge of it well—as happens to a man who tries to see the tip of his nose. Hence, as a general rule, Nature teaches us that an object can never be seen perfectly unless the space between it and the eye is equal, at least, to the length of the face.

If the eye be in the middle of a course with two horses running to their goal along parallel tracks, it will seem to it that they are running to meet one another.

This occurs because the images of the horses that impress themselves upon the eye are moving towards the center of the surface of the pupil of the eye.

But the images of the objects conveyed to the pupil of the eye are distributed to the pupil exactly as they are distributed in the air; and the proof of this is in what follows: when we look at the starry sky, without gazing more fixedly at one star than another, the sky appears all strewn with stars; and their proportions to the eye are the same as in the sky and likewise the spaces between them.

The pupil of the eye contracts in proportion to the increase of light that is reflected in it. The pupil of the eye expands in proportion to the diminution in the daylight, or any other light, that is reflected in it. The eye perceives and recognizes the objects of its vision with greater intensity in proportion as the pupil is more widely dilated; and this can be proved by the case of nocturnal animals, such as cats, and certain birds—as the owl and others—in which the pupil varies in a high degree from large to small, when in the dark or in the light. The eye [out of doors] in an illuminated atmosphere sees darkness behind the windows of houses that [nevertheless] are light.

The pupil of the eye changes to as many different sizes as there are differences in the degrees of brightness and obscurity of the objects that present themselves before it. In this case nature has provided for the visual faculty when it has been irritated by excessive light by contracting the pupil of the eye, and by enlarging this pupil after the manner of the mouth of a purse when it has had to endure varying degrees of darkness.

And here nature works as one who, having too much light in his habitation, blocks up the window halfway or more or less according to the necessity, and who when the night comes throws open the whole of this window in order to see better within this habitation. Nature is here establishing a continual equilibrium, perpetually adjusting and equalizing by making the pupil dilate or contract in proportion to the aforesaid obscurity or brightness that continually presents itself before it.

You will see the process in the case of the nocturnal animals such as cats, screech owls, long eared owls, and suchlike that have the pupil small at midday and very large at night. And it is the same with all land animals and those of the air and of the water but more, beyond all comparison, with the nocturnal animals.

And if you wish to make the experiment with a man, look intently at the pupil of his eye while you hold a lighted candle at a little distance away and make him look at this light as you bring it nearer to him little by little, and you will then see that the nearer the light approaches to it the more the pupil will contract.

The eye that is used to the darkness is hurt on suddenly beholding the light and therefore closes quickly being unable to endure the light. This is due to the fact that the pupil, in order to recognize any object in the darkness to which it has grown accustomed, increases in size, employing all its force to transmit to the receptive part the image of things in shadow. And the light, suddenly penetrating, causes too large a part of the pupil that was in darkness to be hurt by the radiance which bursts in upon it, this being the exact opposite of the darkness to which the eye has already grown accustomed and habituated, and that seeks to maintain itself there, and will not quit its hold without inflicting injury upon the eye.

One might also say that the pain caused by the sudden light to the eye when in shadow arises from the sudden contraction of the pupil, which does not occur except as the result of the sudden contact and friction of the sensitive parts of the eye.

If you would see an instance of this, observe and note carefully the size of the pupil when someone is looking at a dark place, and then cause a candle to be brought before it, and make it rapidly approach the eye, and you will see an instantaneous contraction of the pupil.

The eye, which sees all objects reversed, retains the images for some time. This conclusion is proved by the results; because, the eye having gazed at light retains some impression of it. After looking [at it] there remain in the eye images of intense brightness, that make any less brilliant spot seem dark until the eye has lost the last trace of the impression of the stronger light.

If you look at the sun or other luminous object and then shut your eyes, you will see it again in the same form within your eye for a long space of time: this is a sign that the images enter within it.

The eye will hold and retain in itself the image of a luminous body better than that of a shaded object. The reason is that the eye is in itself perfectly dark and since two things that are alike cannot be distinguished, therefore the night, and other dark objects cannot be seen or recognized by the eye. Light is totally contrary and gives more distinctness, and counteracts and differs from the usual darkness of the eye, hence it leaves the impression of its image.

Since the eye is the window of the soul, the latter is always in fear of being deprived of it, to such an extent that when anything moves in front of it which causes a man sudden fear, he does not use his hands to protect his heart, which supplies life to the head where dwells the lord of the senses, nor his hearing, nor sense of smell or taste. The affrighted sense immediately not contented with shutting the eyes and pressing their lids together with the utmost force, causes him to turn suddenly in the opposite direction; and not as yet feeling secure he covers them with the one hand and stretches out the other to form a screen against the object of his fear.

It is said that the wolf has power by its look to cause men to have hoarse voices.

The basilisk is said to have the power by its glance to deprive of life every living thing.

The ostrich and the spider are said to hatch their eggs by looking at them.

Maidens are said to have power in their eyes to attract to themselves the love of men.

O, mighty process! What talent can avail to penetrate a nature such as this? Who would believe that so small a space could contain the images of all the universe?

What tongue will it be that can unfold so great a wonder? Verily, none! This it is that guides the human discourse to the considering of divine things.