The sun gives spirit and life to plants, and the earth nourishes them with moisture.

Landscapes ought to be represented so that the trees are half in light and half in shadow; but it is better to make them when the sun is covered by clouds, for then the trees are lighted up by the general light of the sky and the general shadow of the earth; and these are so much darker in their parts, in proportion as these parts are nearer to the middle of the tree and to the earth.

[1]

[1]

The landscape has a finer azure [tone] when, in fine weather the sun is at noon than at any other time of the day, because the air is purified of moisture; and looking at it under that aspect you will see the trees of a beautiful green at the outside and the shadows dark towards the middle; and in the remoter distance the atmosphere that comes between you and them looks more beautiful when there is something dark beyond. And still the azure is most beautiful.

The objects seen from the side on which the sun shines will not show you their shadows. But, if you are lower than the sun, you can see what is not seen by the sun and that will be all in shade. The leaves of the trees, which come between you and the sun are of two principal colors that are a splendid luster of green, and the reflection of the atmosphere that lights up the objects that cannot be seen by the sun, and the shaded portions that only face the earth, and the darkest which are surrounded by something that is not dark.

The trees in the landscape that are between you and the sun are far more beautiful than those you see when you are between the sun and them; and this is so because those that face the sun show their leaves as transparent towards the ends of their branches, and those that are not transparent—that is, at the ends—reflect the light; and the shadows are dark because they are not concealed by anything.

The trees, when you place yourself between them and the sun, will only display to you their light and natural color, which, in itself, is not very strong, and, besides this, some reflected lights which, being against a background that does not differ very much from themselves in tone, are not conspicuous; and if you are lower down than they are situated, they may also show those portions on which the light of the sun does not fall and these will be dark.

[1]

[1]

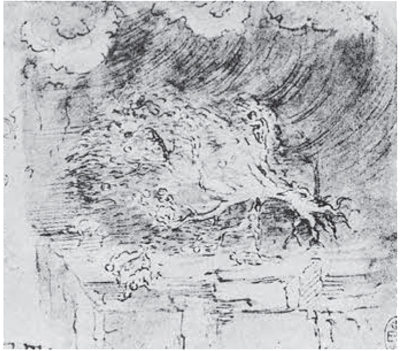

But, if you are on the side whence the wind blows, you will see the trees look very much lighter than on the other sides, and this happens because the wind turns up the under side of the leaves, which, in all trees, is much whiter than the upper sides; and more especially, will they be very light indeed if the wind blows from the quarter where the sun is, and if you have your back turned to it.

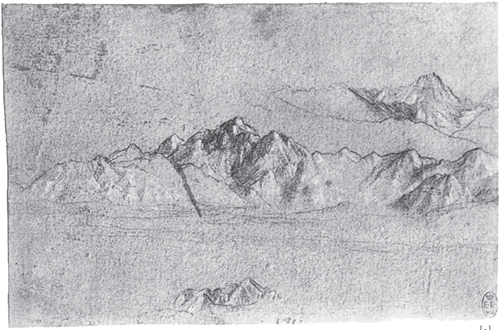

In landscapes that represent [a scene in] winter, the mountains should not be shown blue, as we see in the mountains in the summer.

Among mountains seen from a great distance those will look of the bluest color that are in themselves the darkest; hence when the trees are stripped of their leaves, they will show a bluer tinge that will be in itself darker. Therefore, when the trees have lost their leaves they will look of a gray color, while, with their leaves, they are green. And in proportion as the green is darker than the gray hue, the green will be of a bluer tinge than the gray.

And also, the shadows of trees covered with leaves are darker than the shadows of those trees that have lost their leaves in proportion as the trees covered with leaves are denser than those without leaves—and thus my meaning is proved.

[1]

The definition of the blue color of the atmosphere explains why the landscape is bluer in the summer than in the winter.

I once made the experiment of leaving only one small root on a gourd and keeping this nourished with water; and the gourd brought to perfection all the fruits that it could produce, which were about sixty gourds of the long species. I set myself diligently to consider the source of its life, and I perceived that it was the dew of the night, which steeped it abundantly with its moisture through the joints of its great leaves, and thereby nourished the tree and its offspring, or rather the seeds that were to produce its offspring.

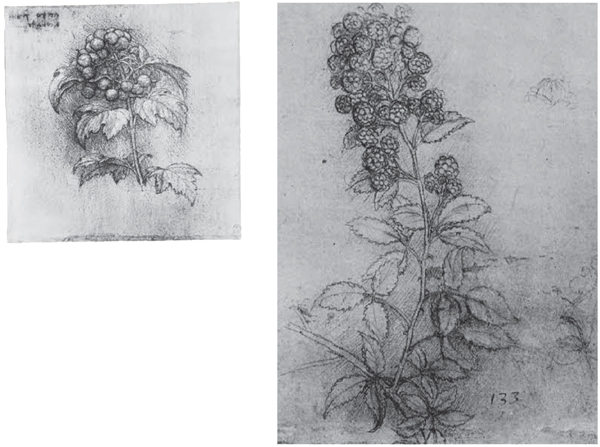

The rule as to the leaves produced on the last of the year’s branches is that on twin branches they will grow in a contrary direction, that is, that the leaves in their earliest growth turn themselves round towards the branch, in such a way that the sixth leaf above grows over the sixth leaf below; and the manner of their turning is that if one turns towards its fellow on the right, the other turns to the left.

The leaf serves as a breast to nourish the branch or fruit that grows in the succeeding year.

Describe landscapes with the wind, and the water, and the setting and rising of the sun.

All the leaves that hung towards the earth by the bending of the shoots with their branches, are turned up side down by the gusts of wind, and here their perspective is reversed; for, if the tree is between you and the quarter of the wind, the leaves that are towards you remain in their natural aspect, while those on the opposite side that ought to have, by being turned over, their points turned towards you.

Of the lights of dark leaves, the lights on such leaves that are darkest in color will most closely resemble the color of the atmosphere reflected in them. And this is due to the fact that the brightness of the illuminated part mingling with the darkness forms of itself a blue color. This brightness proceeds from the blue of the atmosphere, which is reflected in the smooth surface of these leaves, thereby adding to the blueness that this light usually produces when it falls upon dark objects.

But leaves of yellowish green do not, when they reflect the atmosphere, create a reflection that verges on blue; for every object when seen in a mirror takes in part the color of this mirror; therefore the blue of the atmosphere reflected in the yellow of the leaf appears green, because blue and yellow mixed together form a most brilliant green, and therefore the luster on light leaves that are yellowish in color will be a greenish yellow.

If m is the luminous body that lights up the leaf s, all the eyes that see the underside of the leaf will see it of a very beautiful light green because it is transparent. There will be many occasions when the positions of the leaves will be without shadows, and they will have the underside transparent and the right side shining.

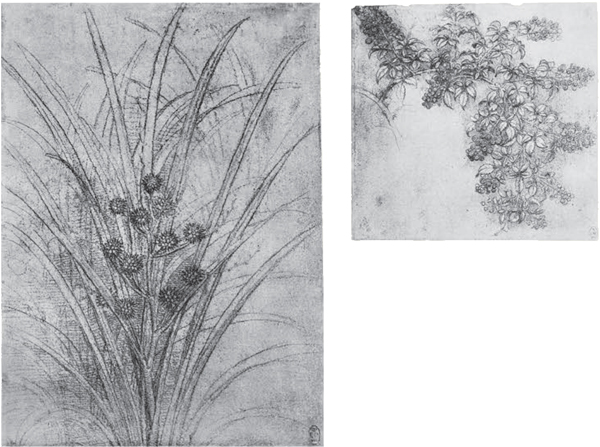

The willow and other similar trees, which are pollarded every third or fourth year, put out very straight branches. Their shadow is towards the center where these branches grow, and near their extremities they cast but little shade because of their small leaves and few and slender branches.

Therefore the branches that rise towards the sky will have but little shadow and little relief, and the branches that point downwards towards the horizon spring from the dark part of the shadow. And they become clearer by degrees down to their extremities, and show themselves in strong relief being in varying stages of brightness against a background of shadow.

That plant will have least shadow which has fewest branches and fewest leaves.

[2]

[2]

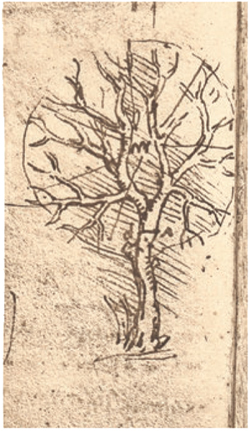

All the branches of a tree at every stage of its height, when put together, are equal in thickness to the trunk [below them].

All the branches of a water [course] at every stage of its course, if they are of equal rapidity, are equal to the body of the main stream.

That portion of a tree which is farthest from the force that strikes it is the most injured by the blow because it bears most strain. Thus nature has foreseen this case by thickening them in that part where they can be most hurt; and most in such trees as grow to great great heights, as pines and the like.

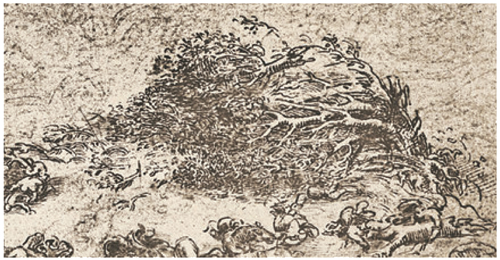

In the composition of leafy trees be careful not to repeat too often the same color of one tree against the same color of another [behind it]; but vary it with a lighter, or a darker, or a stronger green.

[3]

[3]

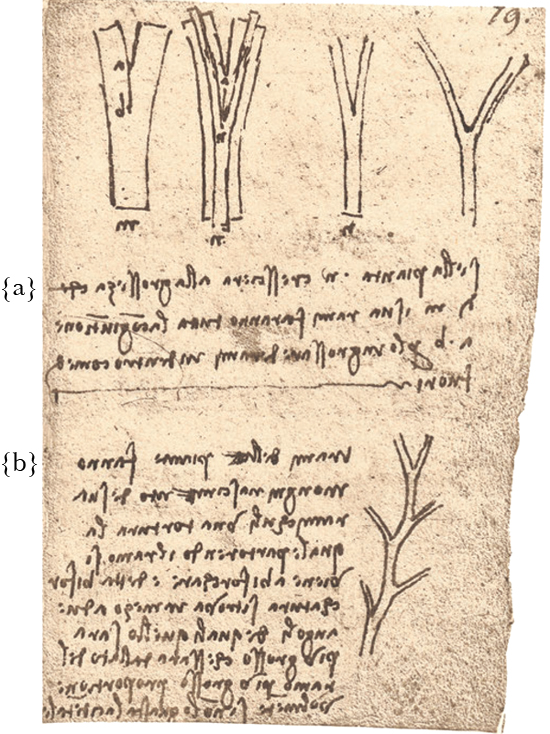

Every year when the boughs of a plant [or tree] have made an end of maturing their growth, they will have made, when put together, a thickness equal to that of the main stem; and at every stage of its ramification you will find the thickness of the said main stem; as: i k, g h, e f, c d, a b, will always be equal to each other; unless the tree is pollard—if so the rule does not hold good.

All the branches have a direction that tends to the center of the tree m.

[4]

[4]

Every branch participates of the central shadow of every other branch and consequently [of that] of the whole tree. The form of any shadow from a branch or tree is circumscribed by the light that falls from the side whence the light comes; and this illumination gives the shape of the shadow, and this may be of the distance of a mile from the side where the sun is.

[5]

[5]

{a} Such as the growth of the ramification of plants is on their principal branches, so is that of the leaves on the shoots of the same plant. These leaves have four modes of growing one above another. The first, which is the most general, is that the sixth always originates over the sixth below; the second is that two third ones above are over the two third ones below; and the third way is that the third above is over the third below. [The last is shown in the fourth sketch.]

[6]

[6]

When the branches that grow the second year above the branch of the preceding year, are not of equal thickness above the antecedent branches, but are on one side, then the vigor of the lower branch is diverted to nourish the one above it, although it may be somewhat on one side.

But if the ramifications are equal in their growth, the veins of the main stem will be straight [parallel] and equidistant at every degree of the height of the plant.

{a} Wherefore, O Painter! you, who do not know these laws! In order to escape the blame of those who understand them, it will be well that you should represent every thing from nature, and not despise such study as those do who work [only] for money.

In general almost all the upright portions of trees curve somewhat turning the convexity towards the South; and their branches are longer and thicker and more abundant towards the South than towards the North. And this occurs because the sun draws the sap towards that surface of the tree which is nearest to it.

And this may be observed if the sun is not screened off by other plants.

[7]

[7]

The space between the insertion of one leaf to the rest is half the extreme length of the leaf or somewhat less, for the leaves are at an interval that is about the third of the width of the leaf.

The elm has more leaves near the top of the boughs than at the base; and the broad [surface] of the leaves varies little as to [angle and] aspect.

A leaf always turns its upper side towards the sky so that it may the better receive, on all its surface, the dew which drops gently from the atmosphere. And these leaves are so distributed on the plant as that one shall cover the other as little as possible, but shall lie alternately one above another as may be seen in the ivy that covers the walls. And this alternation serves two ends. The first is to leave intervals by which the air and sun may penetrate between them. The second reason is that the drops that fall from the first leaf may fall onto the fourth or—in other trees—onto the sixth.

[8]

[8]

In the position of the eye which sees that portion of a tree illuminated which turns towards the light, one tree will never be seen to be illuminated equally with the other. To prove this, let the eye be c which sees the two trees b d that are illuminated by the sun a; I say that this eye c will not see the light in the same proportion to the shade, in one tree as in the other. Because, the tree that is nearest to the sun will display so much the stronger shadow than the more distant one, in proportion as one tree is nearer to the rays of the sun that converge to the eye than the other; etc.

You see that the eye c sees nothing of the tree d but shadow, while the same eye c sees the tree b half in light and half in shade.

When a tree is seen from below, the eye sees the top of it as places within the circle made by its boughs.

Remember, O Painter! that the variety of depth of shade in any one particular species of tree is in proportion to the rarity or density of their branches.

[9]

[9]

[9]

Trees struck by the force of the wind bend to the side towards which the wind is blowing; and the wind being past they bend in the contrary direction, that is, in reverse motion.

[10]

[10]

The shadows of trees placed in a landscape do not display themselves in the same position in the trees on the right hand and those on the left; still more so if the sun is to the right or left. Opaque bodies placed between the light and the eye display themselves entirely in shadow.

{a} The eye when placed between the opaque body and the light sees the opaque body entirely illuminated. When the eye and the opaque body are placed between darkness and light, it will be seen half in shadow and half in light.

[11]

[11]

{a} If the plant n grows to the thickness shown at m, its branches will correspond [in thickness] to the junction a b in consequence of the growth inside as well as outside.

{b} The branches of trees or plants have a twist wherever a minor branch is given off; and this giving off the branch forms a fork; this said fork occurs between two angles of which the largest will be that which is on the side of the larger branch, and in proportion, unless accident has spoilt it.

When a tree has had part of its bark stripped off, nature in order to provide for it supplies to the stripped portion a far greater quantity of nutritive moisture than to any other part. So that because of the first scarcity which has been referred to the bark there grows much more thickly than in any other place. And this moisture has such power of movement that after having reached the spot where its help is needed, it raises itself partly up like a ball rebounding, and makes various buddings and sproutings, somewhat after the manner of water when it boils.

Many trees planted in such a way as to touch, by the second year will have learnt how to dispense with the bark that grows between them and become grafted together; and by this method you will make the walls of the gardens continuous, and in four years you will even have very wide boards.

When many grains or seeds are sown so that they touch and are then covered by a board filled with holes the size of the seeds and left to grow underneath it, the seeds as they germinate will become fixed together and will form a beautiful clump. And if you mix seeds of different kinds together this clump will seem like jasper.

[12]

[12]

The willow and other similar trees, which have their boughs lopped every three or four years, put forth very straight branches, and their shadow is about the middle where these boughs spring; and towards the extreme ends they cast but little shade from having small leaves and few and slender branches.

Hence the boughs that rise towards the sky will have but little shade and little relief. And the branches that are at an angle from the horizon, downwards, spring from the dark part of the shadow and grow thinner by degrees up to their ends, and these will be in strong relief, being in gradations of light against a background of shadow.

That tree will have the least shadow which has the fewest branches and few leaves.

[13]

[13]

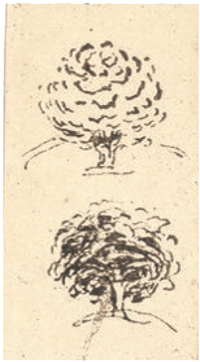

What outlines are seen in trees at a distance against the sky that serves as their background?

The outlines of the ramification of trees, where they lie against the illuminated sky, display a form that more nearly approaches the spherical on proportion as they are remote. And the nearer they are the less they appear in this spherical form; as in the first tree a which, being near to the eye, displays the true form of its ramification. But this shows less in b and is altogether lost in c, where not merely the branches of the tree cannot be seen but the whole tree is distinguished with difficulty.

The trees and plants that are most thickly branched with slender branches ought to have less dark shadow than those trees and plants that, having broader leaves, will cast more shadow.

[14]

[14]

When the leaves are interposed between the light and the eye, then that which is nearest to the eye will be the darkest, and the most distant will be the lightest, not being seen against the atmosphere. This is seen in the leaves which are away from the center of the tree; that is, towards the light.

[15]

[15]

{a} That part of the body will be most illuminated which is hit by the luminous ray coming between right angles.

The colors of the shadows in mountains at a great distance take a most lovely blue, much purer than their illuminated portions. And from this it follows that when the rock of a mountain is reddish the illuminated portions are violet and the more they are lighted the more they display their proper color.

In representing wind, besides the bending of the boughs and the reversing of their leaves towards the quarter whence the wind comes, you should also represent them amid clouds of fine dust mingled with the troubled air.

[16]

[16]

{a} The clouds do not show their rounded forms excepting on the sides that face the sun; on the others the roundness is imperceptible because they are in the shade.

{b} If the sun is in the East and the clouds in the West, the eye placed between the sun and the clouds sees the edges of the rounded forms composing these clouds as dark, and the portions that are surrounded by this dark [edge] are light. And this occurs because the edges of the rounded forms of these clouds are turned towards the upper or lateral sky, which is reflected in them.

{c} Of the redness of the atmosphere near the horizon.

[17]

{a} Both the cloud and the tree display no roundness at all on their shaded side.

I have already been to see a great variety (of atmospheric effects). And lately over Milan towards Lago Maggiore I saw a cloud in the form of an immense mountain full of rifts of glowing light, because the rays of the sun, which was already close to the horizon and red, tinged the cloud with its own hue. And this cloud attracted to it all the little clouds that were near while the large one did not move from its place; thus it retained on its summit the reflection of the sunlight till an hour and a half after sunset, so immensely large was it; and about two hours after sunset such a violent wind arose, that it was really tremendous and unheard of.

[18]

When clouds come between the sun and the eye all the upper edges of their round forms are light, and towards the middle they are dark, and this happens because towards the top these edges have the sun above them while you are below them; and the same thing happens with the position of the branches of trees; and again the clouds, like the trees, being somewhat transparent, are lighted up in part, and at the edges they show thinner.

But, when the eye is between the cloud and the sun, the cloud had the contrary effect to the former, for the edges of its mass are dark and it is light towards the middle. And this happens because you see the same side as faces the sun, and because the edges have some transparency and reveal to the eye that portion which is hidden beyond them, and which, as it does not catch the sunlight like that portion turned towards it, is necessarily somewhat darker. Again, it may be that you see the details of these rounded masses from the lower side, while the sun shines on the upper side and as they are not so situated as to reflect the light of the sun, as in the first instance they remain dark.

The black clouds, which are often seen higher up than those which are illuminated by the sun, are shaded by other clouds, lying between them and the sun.

Again, the rounded forms of the clouds that face the sun show their edges dark because they lie against the light background; and to see that this is true, you may look at the top of any cloud that is wholly light because it lies against the blue of the atmosphere, which is darker than the cloud.

[19]

Observe the motion of the surface of the water which resembles that of hair, and has two motions, of which one goes on with the flow of the surface, the other forms the lines of the eddies; thus the water forms eddying whirlpools one part of which are due to the impetus of the principal current and the other to the incidental motion and return flow.