Force arises from dearth or abundance; it is the child of physical motion, and the grandchild of spiritual motion, and the mother and origin of gravity.

[1]

[1]

Force I define as an incorporeal agency, an invisible power, which by means of unforeseen external pressure is caused by the movement stored up and diffused within bodies that are withheld and turned aside from their natural uses; imparting to these an active life of marvelous power it constrains all created things to change of form and position, and hastens furiously to its desired death, changing as it goes according to circumstances.

When it is slow its strength is increased, and speed enfeebles it. It is born in violence and dies in liberty; and the greater it is, the more quickly it is consumed. It drives away in fury whatever opposes its destruction. It desires to conquer and slay the cause of opposition, and in conquering destroys itself. It waxes more powerful where it finds the greater obstacle. Everything instinctively flees from death. Everything, when under constraint, itself constrains other things. Without force nothing moves.

The body in which it is born grows neither in weight nor in form. None of the movements that it makes are lasting.

It increases by effort and disappears when at rest. The body within which it is confined is deprived of liberty. Often also by its movement it generates new force.

Gravity is limited to the elements of water and earth; but this force is unlimited, and by it infinite worlds might be moved if instruments could be made by which the force could be generated.

Force, with physical motion, and gravity, with resistance are the four external powers on which all actions of mortals depend.

The earth is not in the center of the Sun’s orbit nor at the center of the universe, but in the center of its companion elements, and united with them. And any one standing on the moon, when it and the sun are both beneath us, would see this, our earth, and the element of water upon it just as we see the moon, and the earth would light it as it lights us.

No movement can ever be so slow that a moment of stability is found in it.

That movement is slower which covers less distance in the same time.

That movement is swifter which covers a greater distance in the same time.

Movement can extend to infinite degrees of slowness.

And the power of the movement can extend to infinite degrees of slowness and likewise to infinite degrees of swiftness.

I say that the blue that is seen in the atmosphere is not its own color, but is caused by the heated moisture having evaporated into the most minute imperceptible particles, which the beams of the solar rays attract and cause to seem luminous against the deep intense darkness of the region of fire that forms a covering above them.

Weight, force, a blow, and impetus are the children of movement because they are born from it.

Weight and force always desire their death, and each is maintained by violence.

Impetus is frequently the cause why movement prolongs the desire of the thing moved.

Force is nothing else than a spiritual capacity, an invisible power that is created and implanted by accidental violence by sensible bodies in insensible ones, giving to these a semblance of life; and this life is marvelous in its workings, constraining and transforming in place and shape all created things, running with fury to its own destruction, and producing different effects in its course as occasion requires.

Tarrying makes it great and quickness makes it weak.

It lives by violence and dies from liberty.

It transforms and constrains every body with change of position and form.

Great power gives it great desire of death.

It drives away with fury whatever opposes its destruction.

Transmuter of various forms.

Lives always in hostility to whoever controls it.

Always sets itself against natural desires.

From small beginnings it slowly becomes larger, and makes itself a dreadful and marvelous power.

Always it desires to grow weak and to spend itself.

Itself constrained it constrains every body.

Without it nothing moves.

Without it no sound or voice is heard.

Its true seed is in sentient bodies.

If a power can move a body through a certain space in a certain time it does not necessarily follow that the half of this power will move the whole of the body over half the space in the whole of that time, or over the whole of the space in double the time.

If a power moves a weight a certain distance in a certain time the same power will move the half of this weight double the distance in the same time.

Or this whole power [will move] all the weight half the distance in half the time, or the whole power in the same time will move double the weight half the distance, or the whole power in half the time [will move] the whole weight half the distance.

[2]

[2]

{a} Why does not the weight o remain in its place? It does not remain because it has no resistance. Where will it move to? It will move towards the center [of gravity]. And why by no other line? Because a weight that has no support falls by the shortest road to the lowest point, which is the center of the world. And why does the weight know how to find it by so short a line? Because it is not independent and does not move about in various directions.

Every heavy substance not held back out of its natural place desires to descend more by a direct line than by an arc. This is shown because every body, whatever it may be, that is away from its natural place, which preserves it, desires to regain its first perfection in as brief a space of time as possible. And since the chord is described in a less time than the arc of the same chord it follows from this that every body that is away from its natural place desires to descend more speedily by a chord than by an arc.

A heavy substance of uniform thickness and weight, placed in a position of equilibrium, will have a straight descent with equal height in each of its parts without ever deviating from the position of its first equilibrium, if the air be motionless and of uniform resistance, and this movement will be very slow as will be proved.

But if the heavy substance of uniform thickness be situated slantwise in air of uniform resistance then its descent will be made slantwise and it will be more rapid than the first aforesaid.

I ask if a weight of a pound falling two braccia bury itself in the earth the depth of a hand, how deeply will it bury itself if it falls forty braccia, and how far a weight of two pounds will bury itself if it falls two braccia?

Impetus is that which under another name is termed derived movement, which arises out of primary movement, that is to say, when the movable thing is joined to its mover.

In no part of the derived movement will one ever find a velocity equal to that of the primary movement. This is proved, because at every stage of movement as with the cord of the bow there is a loss of the acquired power that has been communicated to it by its mover. And because every effect partakes of its cause the derived movement of the arrow goes lessening its power by degrees, and thus participates in the power of the bow which as it was produced by degrees is so destroyed.

The impetus impressed by the mover on the movable thing is infused in all the united parts of this movable thing.

If two balls strike together at a right angle one will deviate more from its first course than the other in proportion as it is less than the other.

The part of a log first severed from the end of it by the stroke of the axe flies off to a greater distance than any other part carried away by the same blow.

This is because the part of the log that first receives the blow receives it in the first stage of its power and consequently goes farther. The second part flies a less distance because the fury of the blow has already subsided, the third still less, and so also the fourth.

A body with a thicker, harder surface will cause the objects that strike against it to separate from it with a more powerful and rapid rebound.

An arrow shot from the prow of a ship in the direction in which the ship is moving will not appear to stir from the place at which it was shot if the ship’s movement be equal to that of the arrow.

But if the arrow from such a ship be shot in the direction from whence it is going away with the above mentioned rate of speed, this arrow will be separated from the ship with twice its movement.

[3]

[3]

The heavier the thing the more power attends its movement.

This is seen with jumpers who have their feet joined, who in order to make a greater jump throw back their clenched hands and then move them forward violently as they take off for the jump, finding that by this movement the jump becomes greater.

And there are many who to increase this jump take two heavy stones in their two hands and use them for the same purpose as they used to use their fists; their leap becomes much greater.

If someone descends from one step to another by jumping from one to the other and then you add together all the forces of the percussions and the weights of these jumps, you will find that they are equal to the entire percussion and weight that such a man would produce if he fell by a perpendicular line from the top to the bottom of the height of this staircase.

Furthermore if this man were to fall from a height, striking stage by stage upon objects that would bend in the manner of a spring, in such a way that the percussion from the one to the other was slight, you will find that at the last part of his descent this man will have his percussion as much diminished by comparison with what it would have been in a free and perpendicular line, as it would be if there were taken from it all the percussions joined together that were given at each stage of the said descent upon the aforesaid springs.

Many small blows cause the nail to enter into the wood, but if you join these blows together in one single blow it will have much more power than it had separately in its parts. But if a power of percussion drives a nail entirely into a piece of wood, this same power can be divided into ever so many parts, and though the percussion of these occur on the nail for a long time they can never penetrate to any extent in the said wood.

If a ten-pound hammer drives a nail into a piece of wood with one blow, a hammer of one pound will not drive the nail altogether into the wood in ten blows. Nor will a nail that is less than the tenth part [of the first] be buried more deeply by the said hammer of a pound in a single blow although it may be in equal proportions to the first named, because what is lacking is that the hardness of the wood does not diminish the proportion of its resistance, that is, that it is as hard as at first.

If you wish to treat of the proportions of the movement of the things that have penetrated into the wood when driven by the power of the blow, you have to consider the nature of the weight that strikes and the place where the thing struck buries itself.

All seas have their flow and ebb in the same period, but they seem to vary because the days do not begin at the same time throughout the universe; in such wise as that when it is midday in our hemisphere, it is midnight in the opposite hemisphere; and at the Eastern boundary of the two hemispheres the night begins which follows on the day, and at the Western boundary of these hemispheres begins the day, which follows the night from the opposite side. Hence it is to be inferred that the above mentioned swelling and diminution in the height of the seas, although they take place in one and the same space of time, are seen to vary from the above mentioned causes.

Let the earth make whatever changes it may in its weight, the surface of the sphere of waters can never vary in its equal distance from the center of the world.

If the sea bears down with its weight upon its bed, a man who lay on this bed and had a thousand braccia of water on his back would have enough to crush him.

Quality of the sun:

The sun has substance, shape, movement, radiance, heat, and generative power; and these qualities all emanate from itself without its diminution.

Some say that the sun is not hot because it is not the color of fire but is much paler and clearer. To these we may reply that when liquefied bronze is at its maximum of heat it most resembles the sun in color, and when it is less hot it has more of the color of fire.

[4]

[4]

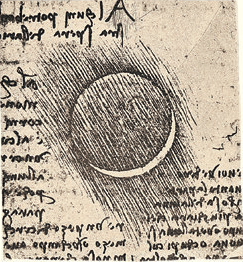

Some might say that the air surrounding the moon as an element catches the light of the sun as our atmosphere does, and that it is this which completes the luminous circle on the body of the moon.

Some have thought that the moon has a light of its own, but this opinion is false, because they have founded it on that dim light seen between the homes of the new moon, which looks dark where it is close to the bright part. And this difference of background arises from the fact that the portion of that background which is conterminous with the bright part of the moon, by comparison with that brightness looks darker than it is; while at the upper part, where a portion of the luminous circle is to be seen of uniform width, the result is that the moon, being brighter there than the medium or background on which it is seen by comparison with that darkness it looks more luminous at that edge than it is.

If you want to see how much brighter the shaded portion of the moon is than the background on which it is seen, conceal the luminous portion of the moon with your hand or with some other more distant object.

The moon has no light in itself; but so much of it as faces the sun is illuminated, and of that illumined portion we see so much as faces the earth. And the moon’s night receives just as much light as is lent it by our waters as they reflect the image of the sun, which is mirrored in all those waters that are on the side towards the sun. The outside or surface of the waters forming the seas of the moon and of the seas of our globe is always ruffled little or much, or more or less. And this roughness causes an extension of the numberless images of the sun that are repeated in the ridges and hollows, the sides and fronts of the innumerable waves; that is to say, in as many different spots on each wave as our eyes find different positions to view them from.

This could not happen if the aqueous sphere that covers a great part of the moon were uniformly spherical, for then the images of the sun would be one to each spectator, and its reflections would be separate and independent and its radiance would always appear circular; as is plainly to be seen in the gilt balls placed on the tops of high buildings. But if those gilt balls were rugged or composed of several little balls, like mulberries, which are a black fruit composed of minute round globules, then each portion of these little balls, when seen in the sun, would display to the eye the luster resulting from the reflection of the sun, and thus, in one and the same body many tiny suns would be seen; and these often combine at a long distance and appear as one.

The stars are visible by night and not by day, because we are beneath the dense atmosphere, which is full of innumerable particles of moisture, each of which independently, when the rays of the sun fall upon it, reflects a radiance. And so these numberless bright particles conceal the stars; and if it were not for this atmosphere the sky would always display the stars against its darkness.

If you look at the stars, cutting off the rays (as may be done by looking through a very small hole made with the extreme point of a very fine needle, placed so as almost to touch the eye), you will see those stars so minute that it would seem as though nothing could be smaller; it is in fact their great distance that is the reason of their diminution, for many of them are very many times larger than the star which is the earth with water. Now reflect what this, our star, must look like at such a distance, and then consider how many stars might be added—both in longitude and latitude—between those stars that are scattered over the darkened sky.

What is that thing which does not give itself, and which if it were to give itself would not exist?

It is the infinite, which if it could give itself would be bounded and finite, because that which can give itself has a boundary with the thing that surrounds it in its extremities, and that which cannot give itself is that which has no boundaries.