The ancient architects, beginning with the Egyptians, were the first to build and construct large cities and castles, public and private buildings of fine form, large and well proportioned.

[1]

An arch is nothing other than a strength caused by two weaknesses; for the arch in buildings is made up of two segments of a circle, and each of these segments being in itself very weak desires to fall, and as the one withstands the downfall of the other the two weaknesses are converted into a single strength.

When once the arch has been set up it remains in a state of equilibrium, for the one side pushes the other as much as the other pushes it; but if one of the segments of the circle weighs more than the other the stability is ended and destroyed, because the greater weight will subdue the less. Next to giving the segments of the circle equal weight it is necessary to load them equally, or you will fall into the same defect as before.

[2]

[2]

That part of the arch that is nearer to the horizontal offers least resistance to the weight placed on it.

The arch that is doubled to four times of its thickness will bear four times the weight that the single arch could carry, and more in proportion as the diameter of its thickness goes a smaller number of times into its length. That is to say that if the thickness of the single arch goes ten times into its length, the thickness of the doubled arch will go five times into its length. Hence as the thickness of the double arch goes only half as many times into its length as that of the single arch does, it is reasonable that it should carry half as much more weight as it would have to carry if it were in direct proportion to the single arch. Hence as this double arch has four times the thickness of the single arch, it would seem that it ought to bear four times the weight; but by the above rule it is shown that it will bear exactly eight times as much.

[3]

[3]

[3]

The way to give stability to the arch is to fill the spandrels with good masonry up to the level of its summit.

[4]

[4]

{a} The inverted arch is better for giving a shoulder than the ordinary one, because the former finds below it a wall resisting its weakness, whilst the latter finds in its weak part nothing but air.

[5]

[5]

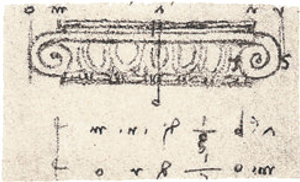

{a} The plinth must be as broad as the thickness of the wall against which the plinth is built.

[6]

[6]

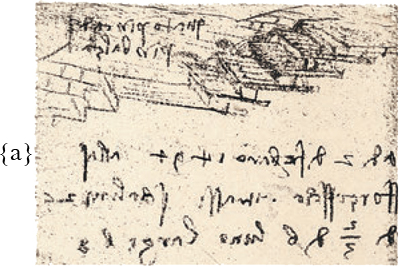

{a} On the second day of February 1494. At Sforzesca I drew twenty-five steps, 2/3 braccia to each, and eight braccia wide.

[7]

[7]

{a} The construction of the stairs: The stairs c d go down to f g, and in the same way f g goes down to h k.

[8]

[8]

{a} The way in which the poles ought to be placed for tying bunches of juniper on to them. These poles must lie close to the framework of the vaulting and tie the bunches on with osier withes, so as to clip them even afterwards with shears.

{b} Let the distance form one circle to another be half a braccia; and the juniper [sprigs] must lie top downwards, beginning from below.

{c} Round this column tie four poles to which willows about thick as a finger must be nailed and then begin from the bottom and work upwards with bunches of juniper sprigs, the tops downwards, that is, upside down.

[9]

[9]

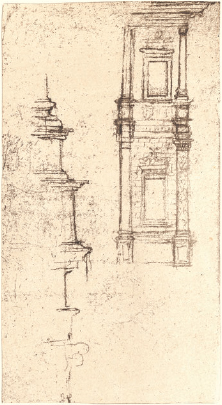

{a} It never looks well to see the roofs of a church; they should rather be flat and the water should run off by gutters made in the frieze.

[10]

[10]

{a} This building is inhabited below and above; the way up is by the campaniles, and in going up one has to use the platform, where the drums of the four domes are, and this platform has a parapet in front, and none of these domes communicate with the church, but they are quite separate.

[11]

[11]

{a} This edifice would also produce a good effect if only the part above the lines a b, c d were executed.

[12]

[12]

{a} The main division of the façade of this palace is into two portions; that is to say, the width of the court-yard must be half the whole façade.

{b} In the angle a may be the keeper of the stable.

{c} Jousting in boats, that is, the men are to be in boats.

The rooms that you mean to use for dancing or to make different kinds of jumps or various movements with a crowd of people should be on the ground floor, for I have seen them collapse and so cause the death of many. And above all see that every wall, however thin it may be, has its foundations on the ground or on well planted arches.

Let the mezzanines of the dwellings be divided by walls made of narrow bricks, and without beams because of the risk of fire.

All the privies should have ventilation openings through the thickness of the walls, and in such a way that air may come in through the roofs.

Let the mezzanines be vaulted, and these will be so much the stronger as they are fewer in number.

Let the bands of oak be enclosed in the walls to prevent them from being damaged by fire.

Let the privies be numerous and be connected one with another, so that the smell may not spread through the rooms, and their doors should all close automatically.

[13]

{a} The front a m will give light to the rooms.

a e will be 6 braccia—a b 8 braccia—b e 30 braccia, in order that the rooms under the porticoes may be lighted. c d f is the place where the boats come to the houses to be unloaded.

In order to render this arrangement practicable, and in order that the inundation of the rivers may not penetrate into the cellars, it is necessary to chose an appropriate situation, such as a spot near a river that can be diverted into canals in which the level of the water will not vary either by inundations or drought. The construction is shown below; and make choice of a fine river, which the rains do not render muddy, such as the Ticino, the Adda and many others.

The construction to oblige the waters to keep constantly at the same level will be a sort of dock, situated at the entrance of the town; or better still, some way within, in order that the enemy may not destroy it.

[14]

[14]

[14]

[14]

The main underground channel does not receive turbid water, but that water runs in the ditches outside the town with four mills at the entrance and four at the outlet, and this may be done by damming the water above Romorantin.

There should be fountains made in each piazza.

[15]

[15]

{a} 30 braccia wide on each side; the lower entrance leads into a hall 10 braccia wide and 30 braccia long with four recesses, each with a chimney.

[16]

[16]

{a} The first story [or terrace] must be entirely solid.

[17]

[17]

{a} Steps at [the castle of] Urbino.

[18]

[18]

The manner in which one must arrange a stable. You must first divide its width in three parts, its depth matters not; and let these three divisions be equal. The middle part shall be for the use of the stablemasters; the two side ones for the horses. Now, in order to attain to what I promise, that is to make this place, contrary to the general custom, clean and neat: as to the upper part of the stable, i.e., where the hay is, that part must have at its outer end a window through which by simple means the hay is brought up to the loft, as is shown by the machine E. And let this be erected in a place six braccia wide, and as long as the stable, as seen at k p.

The other two parts, which are on either side of this, are again divided; those nearest to the hay-loft are p s, and only for the use and circulation of the servants belonging to the stable; the other two, which reach to the outer walls, are seen at s k, and these are made for the purpose of giving hay to the mangers, by means of funnels, narrow at the top and wide over the manger, in order that the hay should not choke them. They must be well plastered and clean. As to the giving the horses water, the troughs must be of stone and above them [cisterns of] water. The mangers may be opened as boxes are uncovered by raising the lids.

[4]

[19]

{a} On St. Mary’s day in the middle of August, at Cesena, 1502.

[20]

[20]

{a} The bridge of Pera at Constantinople, 40 braccia wide, 70 braccia high above the water, 600 braccia long; that is 400 over the sea and 200 on the land, thus making its own abutments.

[21]

[21]

The roads m are six braccia higher than the roads p s, and each road must be 20 braccia wide and have 1/2 braccio slope from the sides towards the middle; and in the middle let there be at every braccio an opening, one braccio long and one finger wide, where the rain water may run off into hollows made on the same level as p s. And on each side at the extremity of the width of the said road let there be an arcade, six braccia broad, on columns; and understand that he who would go through the whole place by the high level streets can use them for this purpose, and he who would go by the low level can do the same.

By the high streets no vehicles and similar objects should circulate, but they are exclusively for the use of gentlemen. The carts and burdens for the use and convenience of the inhabitants have to go by the low ones.

One house must turn its back to the other, leaving the lower streets between them. Provisions, such as wood, wine, and such things are carried in by the doors n, and privies, stables, and other fetid matter must be emptied away underground.

From one arch to the next must be 300 braccia, each street receiving its light through the openings of the upper streets, and at each arch must be a winding stair on a circular plan because the corners of square ones are always fouled. They must be wide, and at the first vault there must be a door entering into public privies and the said stairs lead from the upper to the lower streets and the high level streets begin outside the city gates and slope up till at these gates they have attained the height of six braccia. Let such a city be built near the sea or a large river in order that the dirt of the city may be carried off by the water.

[A plan for laying out a water garden:]

The staircase is one braccio and three quarters wide and it is bent like a knee, and altogether it is sixteen braccia with thirty-two steps half a braccio wide and a quarter high; and the landing where the staircase turns is two braccia wide and four long, and the wall that divides one staircase from the other is half a braccio; but the breadth of the staircase will be two braccia and the passage half a braccio wider; so that this large room will come to be twenty-one braccia long and ten and half braccia wide, and so it will serve well; and let us make it eight braccia high, although it is usual to make the height tally with the width; such rooms however seem to me depressing for they are always somewhat in shadow because of their great height, and the staircases would then be too steep because they would be straight.

By means of the mill I shall be able at any time to produce a current of air; in the summer I shall make the water spring up fresh and bubbling, and flow along in the space between the tables. The channel may be half a braccio wide, and there should be vessels there with wines always of the freshest, and other water should flow through the garden, moistening the orange trees and citron trees according to their needs. These citron trees will be permanent, because their situation will be so arranged that they can easily be covered over, and the warmth that the winter season continually produces will be the means of preserving them far better than fire, for two reasons: one is that this warmth of the springs is natural and is the same as warms the roots of all the plants; the second is that the fire gives warmth to these plants in an accidental manner, because it is deprived of moisture and is neither uniform nor continuous, being warmer at the beginning than at the end, and very often it is overlooked through the carelessness of those in charge of it.

The herbage of the little brooks ought to be cut frequently so that the clearness of the water may be seen upon its shingly bed, and only those plants should be left that serve the fishes for food, such as watercress and other plants like these.

The fish should be such as will not make the water muddy, that is to say, eels must not be put there nor tench, nor yet pike because they destroy the other fish.

By means of the mill you will make many water conduits through the house, and springs in various places, and a certain passage where, when anyone passes, from all sides below the water will leap up, and so it will be there ready in case anyone should wish to give a shower-bath from below to the women or others who shall pass there.

Overhead we must construct a very fine net of copper that will cover over the garden and shut in beneath it many different kinds of birds, and so you will have perpetual music together with the scents of the blossom of the citrons and the lemons.

With the help of the mill I will make unending sounds from all sorts of instruments, which will sound for so long as the mill shall continue to move.

[22]

[22]

{a} Let the width of the streets be equal to the average height of the houses.

[23]

[23]

{a} First write the treatise on the causes of the giving way of walls and then, separately, treat of the remedies.

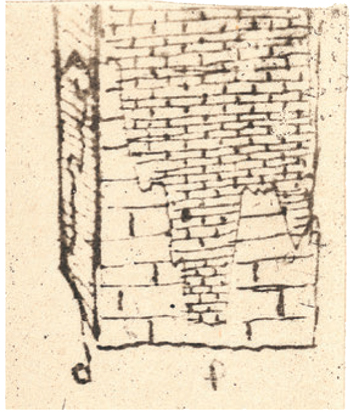

Parallel cracks are constantly appearing in buildings erected in mountainous places where the rocks are stratified and the stratification runs obliquely, for, in these oblique seams, water and other moisture often penetrates, bearing with it a quantity of greasy and slimy earth; and, since this stratification does not continue down to the bottom of the valleys, the rocks go slipping down their slope, and never end their movement until they have descended to the bottom of the valley, carrying with them after the manner of a boat such part of the building as they have severed from the rest.

{b} The remedy for this is to build numerous piers under the wall that is slipping away, with arches from one to another, and well rooted. And let the pillars have their bases firmly set in the stratified rock so that they may not break away.

{c} In order to find the solid part of these strata, it is necessary to make a shaft at the foot of the wall of great depth through the strata; and in this shaft, on the side from which the hill slopes, smooth and flatten a space one palm wide from the top to the bottom; and after some time this smooth portion made on the side of the shaft, will show plainly which part of the hill is moving.

[24]

{a} The window a is the cause of the crack at b; and this crack is increased by the pressure of n and m, which sink or penetrate into the soil in which foundations are built more than the lighter portion at b. Besides, the old foundation under b has already settled, and this the piers n and m have not yet done. Hence the part b does not settle down perpendicularly; on the contrary, it is thrown outwards obliquely, and it cannot on the contrary be thrown inwards, because a portion like this, separated from the main wall, is larger outside than inside and the main wall, where it is broken, is of the same shape and is also larger outside than inside; therefore, if this separate portion were to fall inwards the larger would have to pass through the smaller—which is impossible. Hence it is evident that the portion of the semicircular wall when disunited from the main wall will be thrust outwards, and not inwards as the adversary says.

{b} When a dome or a half-dome is crushed from above by an excess of weight the vault will give way, forming a crack that diminishes towards the top and is wide below, narrow on the inner side and wide outside; as is the case with the outer husk of a pomegranate, divided into many parts lengthwise; for the more it is pressed in the direction of its length, that part of the joints will open most, which is most distant from the cause of the pressure; and for that reason the arches of the vaults of any apse should never be more loaded than the arches of the principal building. Because that which weighs most, presses most on the parts below, and they sink into the foundations; but this cannot happen to lighter structures like the said apses.

{c} Which of these two cubes will shrink the more uniformly: the cube A resting on the pavement, or the cube b suspended in the air, when both cubes are equal in weight and bulk, and of clay mixed with equal quantities of water?

{d} The cube placed on the pavement diminishes more in height than in breadth, which the cube above, hanging in the air, cannot do. Thus it is proved. The cube shown above is better shown here below.

{e} The final result of the two cylinders of damp clay that is a and b will be the pyramidal figures below c and d. This is proved thus: The cylinder a resting on block of stone being made of clay mixed with a great deal of water will sink by its weight, which presses on its base, and in proportion as it settles and spreads, all the parts will be somewhat nearer to the base, because that is charged with the whole weight, etc.; and the case will be the same with the weight of b, which will stretch lengthwise in proportion as the weight at the bottom is increased, and the greatest tension will be the neighborhood of the weight that is suspended by it.

[25]

{a} Of cracks in walls, which are wide at the bottom and narrow at the top, and of their causes.

That wall which does not dry uniformly in an equal time, always cracks.

{b} A wall though of equal thickness will not dry with equal quickness if it is not everywhere in contact with the same medium. Thus, if one side of a wall were in contact with a damp slope and the other were in contact with the air, then this latter side would remain of the same size as before; that side which dries in the air will shrink or diminish and the side which is kept damp will not dry. And the dry portion will break away readily from the damp portion because the damp part not shrinking in the same proportion does not cohere and follow the movement of the part that dries continuously.

Of arched cracks, wide at the top, and narrow below.

{c} Arched cracks, wide at the top and narrow below are found in walled-up doors, which shrink more in their height than in their breadth, and in proportion as their height is greater than their width, and as the joints of the mortar are more numerous in the height than in the width.

{d} The crack diminishes less in r o than in m n, in proportion as there is less material between r and o than between n and m.

{e} Any crack made in a concave wall wide below and narrow at the top; and this originates, as is here shown at bed, in the side figure.

{f} 1. That which gets wet increases in proportion to the moisture it imbibes.

{g} 2. And a wet object shrinks, while drying, in proportion to the amount of moisture that evaporates from it.

[26]

[26]

{a} The cracks in walls will never be parallel unless the part of the wall that separates from the remainder does not slip down.

That is to say that the walls must be all built up equally, and by degrees, to equal heights all round the building, and the whole thickness at once, whatever kind of walls they may be. And although a thin wall dries more quickly than a thick one it will not necessarily give way under the added weight day by day and thus, although a thin wall dries more quickly than a thick one, it will not give way under the weight that the latter may acquire from day to day. Because if double the amount of it dries in one day, one of double the thickness will dry in two days or thereabouts; thus the small addition of weight will be balanced by the smaller difference of time. The adversary says that a, which projects, slips down. And here the adversary says that r slips and not c.

The part of the wall which does not slip is that in which the obliquity projects and overhangs the portion that has parted from it and slipped down.

When the crevice in the wall is wider at the top than at the bottom, it is a manifest sign that the cause of the fissure in the wall is remote from the perpendicular line through the crevice.

[27]

[27]

The first and most important thing is stability.

{a} As to the foundations and other public buildings, the depths of the foundations must be at the same proportions to each other as the weight of material that is to be placed upon them.

That beam which is more than 20 times as long as its greatest thickness will be of brief duration and will break in half; and remember, that the part built into the wall should be steeped in hot pitch and filleted with oak boards likewise so steeped. Each beam must pass through its walls and be secured beyond the walls with sufficient chaining, because in consequence of earthquakes the beams are often seen to come out of the walls and bring down the walls and floors; whilst if they are chained they will hold the walls strongly together and the walls will hold the floors.

Again I remind you never to put plaster over timber. Since by expansion and shrinking of the timber produced by damp and dryness such floors often crack, and once cracked their divisions gradually produce dust and an ugly effect. Again remember not to lay a floor on beams supported on arches; for, in time the floor that is made on beams settles somewhat in the middle while that part of the floor that rests on the arches remains in its place; hence, floors laid over two kinds of supports look, in time, as if they were made in hills.

[28]

[28]

Stones laid in regular courses from bottom to top and built up with an equal quantity of mortar settle equally throughout, when the moisture that made the mortar soft evaporates.

[29]

[29]

{a} In the courtyard, the walls must be half the height of its width, that is, if the court be 40 braccia, the house must be 20 high as regards the walls of the said courtyard; and this courtyard must be half as wide as the whole front.

[30]

{a} A building should always be detached on all sides so that its form may be seen.