Wisdom is the daughter of experience.

[1]

[1]

Of the selection of beautiful faces: it seems to me to be no small charm in a painter when he gives his figures a pleasing air, this grace, if he have it not by nature, he may acquire by incidental study in this way.

Look about you and take the best parts of many beautiful faces, of which the beauty is confirmed rather by public fame than by your own judgment; for you might be mistaken and choose faces that have some resemblance to your own. For it would seem that such resemblances often please us; and if you should be ugly, you should select faces that were not beautiful and you would then make ugly faces, as many painters do. For often a master’s work resembles himself. So select beauties as I tell you, and fix them in your mind.

If you, who draw, desire to study well and to good purpose, always go slowly to work in your drawing; and discriminate in the lights, which have the highest degree of brightness, and to what extent and likewise in the shadows, which are those that are darker than the others and in what way they intermingle; then their masses and the relative proportions of one to the other. And note in their outlines, which way they tend; and which part of the lines is curved to one side or the other, and where they are more or less conspicuous and consequently broad or fine. And finally, that your light and shade blend without strokes and borders [but] looking like smoke. And when you have thus schooled your hand and your judgment by such diligence, you will acquire rapidity before you are aware.

Of a method of learning well by heart: when you want to know a thing you have studied in your memory proceed in this way: when you have drawn the same thing so many times that you think you know it by heart, test it by drawing it without the model; but have the model traced on flat thin glass and lay this on the drawing you have made without the model, and note carefully where the tracing does not coincide with your drawing, and where you find you have gone wrong; and bear in mind not to repeat the same mistakes. Then return to the model, and draw the part in which you were wrong again and again till you have it well in your mind. If you have no flat glass for tracing on, take some very thin kidskin parchment, well oiled and dried. And when you have used it for one drawing you can wash it clean with a sponge and make a second.

Of the order of learning to draw: first draw from drawings by masters done from works of art and from nature and not from memory. And having acquired that practice, under the criticism of his master, he should next practice drawing objects in relief of a good style.

Of studying in the dark, when you wake, or in bed before you go to sleep: I myself have proved it to be of no small use, when in bed in the dark, to recall in fancy the external details of forms previously studied, or other noteworthy things conceived by subtle speculation; and this is certainly an admirable exercise, and useful for impressing things on the memory.

In objects of minute size the extent of error is not so perceptible as in large ones; and the reason is that if this small object is a representation of a man or of some other animal, from the immense diminution the details cannot be worked out by the artist with the finish that is requisite. Hence it is not actually complete; and, not being complete, its faults cannot be determined.

For instance: look at a man at a distance of 300 braccia and judge attentively whether he be handsome or ugly, or very remarkable or of ordinary appearance. You will find that with the utmost effort you cannot persuade yourself to decide. And the reason is that at such a distance the man is so much diminished that the character of the details cannot be determined. And if you wish to see how much this man is diminished [by distance] hold one of your fingers at a span’s distance from your eye, and raise or lower it till the top joint touches the feet of the figure you are looking at, and you will see an incredible reduction. For this reason we often doubt as to the person of a friend at a distance.

[2]

To draw a head in which the features shall agree with the turn and bend of the head, pursue this method. You know that the eyes, eyebrows, nostrils, corners of the mouth, and sides of the chin, the jaws, cheeks, ears and all the parts of a face are squarely and straightly set upon the face.

Therefore when you have sketched the face draw lines passing from one corner of the eye to the other; and so for the placing of each feature; and after having drawn the ends of the lines beyond the two sides of the face, look if the spaces inside the same parallel lines on the right and on the left are equal. But be sure to remember to make these lines to the point of sight.

If you want to acquire facility for bearing in mind the expression of a face, first make yourself familiar with a variety of [forms of] several heads, eyes, noses, mouths, chins and cheeks, and necks and shoulders. And to put a case, noses are of 10 types: straight, bulbous, hollow, prominent above or below the middle, aquiline, regular, flat, round, or pointed. These hold good as to profile. In full face they are of 11 types; these are equal, thick in the middle, thin in the middle, with the tip thick and the root narrow, or narrow at the tip and wide at the root; with the nostrils wide or narrow, high or low, and the openings wide or hidden by the point.

And you will find an equal variety in the other details; which things you must draw from nature and fix them in your mind. Or else, when you have to draw a face by heart, carry with you a little book in which you have noted such features; and when you have cast a glance at the face of the person you wish to draw, you can look, in private, which nose or mouth is most like, or there make a little mark to recognize it again at home.

[3]

[3]

Of a mode of drawing a place accurately: have a piece of glass as large as a half sheet of royal folio paper and set thus firmly in front of your eyes that is, between your eye and the thing you want to draw; then place yourself at a distance of 2/3 of a braccia from the glass, fixing your head with a machine in such a way that you cannot move it at all. Then shut or entirely cover one eye and with a brush or red chalk draw upon the glass that which you see beyond it. Then trace it on paper from the glass, afterwards transfer it on to good paper, and paint it if you like, carefully attending to the aerial perspective.

[4]

[4]

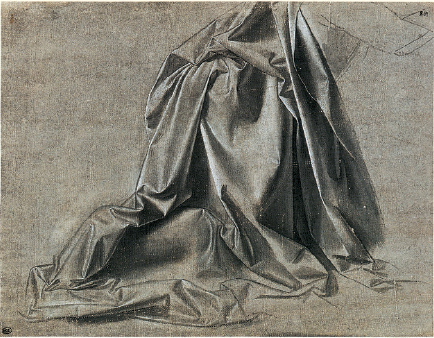

Of the nature of the folds in drapery: that part of a fold which is farthest from the ends where it is confined will fall most nearly in its natural form. Every thing by nature tends to remain at rest. Drapery, being of equal density and thickness on its wrong side and on its right, has a tendency to lie flat; therefore when you give it a fold or plait forcing it out of its flatness note well the result of the constraint in the part where it is most confined; and the part that is farthest from this constraint you will see replaces most into the natural state; that is to say, lies free and flowing.

[5]

[5]

You ought not to give to drapery a great confusion of many folds, but rather only introduce them where they are held by the hands or the arms; the rest you may let fall simply where it is its nature to flow; and do not let the nude forms be broken by too many details and interrupted folds.

How draperies should be drawn from nature: that is to say, if you want to represent woolen cloth draw the folds from that; and if it is to be silk, or fine cloth or coarse, or of linen or of crepe, vary the folds in each and do not represent dresses, as many do, from models covered with paper or thin leather, which will deceive you greatly.

[6]

[6]

[6]

When you draw from nature stand at a distance of 3 times the height of the object you wish to draw.

Compose subjects, the studies for which should be taken from natural actions and made from time to time, as circumstances allow; and pay attention to them in the streets and piazza and fields, and note them down with a brief indication of the forms. Thus for a head make an O, and for an arm a straight or a bent line, and the same for the legs and the body, and when you return home work out these notes in a complete form.

[7]

[7]

[7]

Let your sketches of historical pictures be swift and the working out of the limbs not be carried too far, but limited to the position of the limbs, which you can afterwards finish as you please and at your leisure.

On the site of the studio: small rooms or dwellings discipline the mind, large ones weaken it.

[8]

[8]

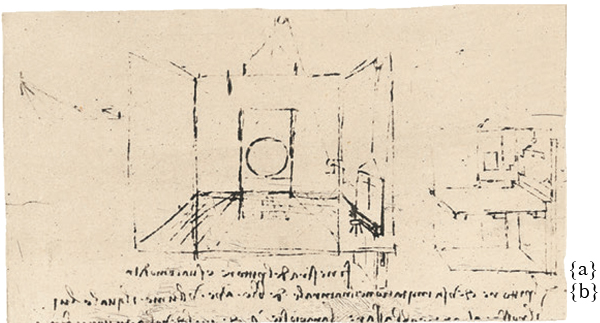

{a} The painter’s window and its advantage.

{b} The painter who works from nature should have a window, which he can raise and lower. The reason is that sometimes you will want to finish a thing you are drawing close to the light.

Let a b c d be the chest on which the work may be raised or lowered, so that the work moves up and down and not the painter. And every evening you can let down the work and shut it up above so that in the evening it may be in the fashion of a chest, which, when shut up, may serve the purpose of a bench.

A broad light high up and not too strong will render the details of objects very agreeable.

The light for drawing from nature should be high up, and come from the North in order that it may not vary. And if you have it from the South, keep the window screened with cloth, so that with the sun shining the whole day the light may not vary. The height of the light should be so arranged as that every object shall cast a shadow on the ground of the same length as itself.

In selecting the light that gives most grace to faces, if you should have a courtyard that you can at pleasure cover with a linen awning that light will be good. Or when you want to take a portrait, do it in dull weather, or as evening falls, making the sitter stand with his back to one of the walls of the courtyard. Note in the streets, as evening falls, the faces of the men and women, and when the weather is dull, what softness and delicacy you may perceive in them. Hence, O Painter! Have a court arranged with the walls tinted black and a narrow roof projecting within the walls. It should be 10 braccia wide and 20 braccia long and 10 braccia high and covered with a linen awning. Or else paint a work towards evening or when it is cloudy or misty, and this is a perfect light.

An object will display the greatest difference of light and shade when it is seen in the strongest light, as by sunlight, or, at night, by the light of a fire. But this should not be much used in painting because the works remain crude and ungraceful.

An object seen in a moderate light displays little difference in the light and shade; and this is the case towards evening or when the day is cloudy, and works then painted are tender and every kind of face becomes graceful. Thus, in everything extremes are to be avoided. Too much light gives crudeness; too little prevents our seeing. The medium is best.

To the end that well-being of the body may not injure that of the mind, the painter or draughtsman must remain solitary, and particularly when intent on those studies and reflections that will constantly rise up before his eye, giving materials to be well stored in the memory.

While you are alone you are entirely your own [master] and if you have one companion you are but half your own, and the less so in proportion to the indiscretion of his behavior. And if you have many companions you will fall deeper into the same trouble. If you should say: “I will go my own way and withdraw apart, the better to study the forms of natural objects,” I tell you, you will not be able to help often listening to their chatter.

And so, since one cannot serve two masters, you will badly fill the part of a companion, and carry out your studies of art even worse. And if you say: “I will withdraw so far that their words cannot reach me and they cannot disturb me,” I can tell you that you will be thought mad. But, you see, you will at any rate be alone.

And if you must have companionship find it in your studio. This may assist you to have the advantages that arise from various speculations. All other company may be highly mischievous.

A painter needs such mathematics as belong to painting. And the absence of all companions who are alienated from his studies; his brain must be easily impressed by the variety of objects that successively come before him, and also free from other cares. And if, when considering and defining one subject, a second subject intervenes—as happens when an object occupies the mind—then he must decide which of these cases is the more difficult to work out, and follow that up until it becomes quite clear, and then work out the explanation of the other.

And above all he must keep his mind as clear as the surface of a mirror, which assumes colors as various as those of the different objects. And his companions should be like him as to their studies, and if such cannot be found he should keep his speculations to himself alone, so that at last he will find no more useful company [than his own].

I say and insist that drawing in company is much better than alone, for many reasons. The first is that you would be ashamed to be seen behindhand among the students, and such shame will lead you to careful study. Secondly, a wholesome emulation will stimulate you to be among those who are more praised than yourself, and this praise of others will spur you on. Another is that you can learn from the drawings of others who do better than yourself; and if you are better than they, you can profit by your contempt for their defects, while the praise of others will incite you to further merits.

A painter ought to be curious to hear the opinions of everyone on his work. Certainly while a man is painting he ought not to shrink from hearing every opinion. For we know very well that a man, though he may not be a painter, is familiar with the forms of other men and very capable of judging whether they are humpbacked, or have one shoulder higher or lower than the other or too big a mouth or nose, and other defects. And as we know that men are competent to judge of the works of nature, how much more ought we to admit that they can judge of our errors, since you know how much a man may be deceived in his own work.

And if you are not conscious of this in yourself study it in others and profit by their faults. Therefore be curious to hear with patience the opinions of others, consider and weigh well whether those who find fault have ground or not for blame, and if so, amend. But if not, make as though you had not heard, or if he should be a man you esteem show him by argument the cause of his mistake.

We know very well that errors are better recognized in the works of others than in our own; and that often, while reproving little faults in others, you may ignore great ones in yourself. To avoid such ignorance, in the first place make yourself a master of perspective, then acquire perfect knowledge of the proportions of men and other animals, and also as far as concerns the forms of buildings and other objects that are on the face of the earth. These forms are infinite, and the better you know them the more admirable will your work be.

And in cases where you lack experience, do not shrink from drawing them from nature. But, to judge your own pictures I say that when you paint you should have a flat mirror and often look at your work as reflected in it, when you will see it reversed, and it will appear to you like some other painter’s work, so you will be better able to judge of its faults than in any other way.

Again, it is well that you should often leave off work and take a little relaxation, because when you come back to it you are a better judge; for sitting too close at work may greatly deceive you. Again, it is good to retire to a distance, because the work looks smaller and your eye takes in more of it at glance and sees more easily the discords or disproportion in the limbs and colors of the objects.

Those who are in love with practice without knowledge are like the sailor who gets into a ship without rudder or compass and who never can be certain whether he is going. Practice must always be founded on sound theory, and to this, perspective is the guide and the gateway. And without this nothing can be done well in the matter of drawing.

I know that many will call this useless work; and they will be those of whom Demetrius declared that he took no more account of the wind that came out their mouth in words, than of that they expelled from their lower parts. Men who desire nothing but material riches and are absolutely devoid of that wisdom which is the food and the only true riches of the mind. For so much worthier as the soul is than the body, so much nobler are the possessions of the soul than those of the body. And often, when I see one of these men take this work in his hand, I wonder that he does not put it to his nose, like a monkey, or ask me if it is something good to eat.

I am fully conscious that, not being a literary man, certain presumptuous persons will think that they may reasonably blame me, alleging that I am not a man of letters. Foolish folks! Do they not know that I might retort as Marius did to the Roman Patricians by saying that they, who deck themselves but in the labors of others will not allow me my own. They will say that I, having no literary skill, cannot properly express that which I desire to treat of, but they do not know that my subjects are to be dealt with by experience rather than by words. And [experience] has been the mistress of those who wrote well. And so, as mistress, I will cite her in all cases.

Though I may not, like them, be able to quote other authors, I shall rely on that which is much greater and more worthy: on experience, the mistress of their Masters. Why go about puffed up and pompous, dressed decorated with [the fruits], not of their labors, but of those of others. And they will not allow me my own. They will scorn me as an inventor; but how much more might they—who are not inventors but vaunters and declaimers of the works of others—be blamed.