7

When Ashikaga Yoshimasa first made his home at the Higashiyama retreat in 1483, the two main buildings were the tsunenogosho, his living quarters, and the kaisho, the “meeting place.” These two buildings have since disappeared, but we know from surviving diaries and other documents not only their external dimensions but how they were divided into rooms with different purposes. We know even which paintings embellished the walls and the fusuma. These and the rest of the buildings of the retreat must have constituted one of the loveliest sites in all Japan: buildings, gardens, and superb natural surroundings.

The tsunenogosho, the first structure to be completed, was a small building,1 measuring about forty-two feet north–south and thirty-six feet east–west. These dimensions were not accidental but were modeled on those of the Seiryo Pavilion in the imperial palace.2

According to the reconstructed plan of the tsunenogosho, Yoshimasa’s sleeping place, a six-mat room, was in the very center of the building. Perhaps it was believed that surrounding his bedroom with other rooms would afford protection in case of an attack, but it is surprising that Yoshimasa, who loved gardens, should have agreed to sleep in a room that did not open out onto a garden or another view.

East of the bedroom was an eight-mat room that during the day served as Yoshimasa’s office, and to the northeast was a four-mat study. Other rooms were intended variously as a dining room, a room where the dōbōshū would await Yoshimasa’s commands, and reception rooms for guests. The modesty of the structure indicates that it was designed as a retreat for a man who was weary of worldly pomp.

Yoshimasa encountered many setbacks in carrying out his plans, mainly in finding money, but they did not swerve him from his resolve of building a retreat that exactly accorded with his tastes. He refused to allow modifications made in the interests of economy that might mar the beauty of the retreat. A perfectionist in architecture, no less than in painting, he studied other famous buildings before deciding what would be built at the retreat. While planning the kaisho, he paid visits in 1484 and 1485 to the Kinkakuji and spent several days there. Even more than the Golden Pavilion itself, he was impressed by the ensemble of temple buildings that met his eyes after climbing to the top of the pavilion.

Yoshimasa’s study of the Kinkaku-ji did not tempt him to imitate its splendor. Compared with the Golden Pavilion, the Silver Pavilion would be no more than a shy sibling. Rather, his purpose in visiting the Kinkaku-ji was not to find architectural features to incorporate in the Ginkaku but to immerse himself in the beauty of great architecture. He probably did not hope that his Silver Pavilion would be the equal of the Golden Pavilion but that it would create a feeling of architectural harmony, the most one could hope for in a world that had sadly declined from Yoshimitsu’s day.

During the years that Yoshimasa was busily erecting one palace after another inside the city of Kyoto, he had always borne in mind the surroundings of the new buildings and tried to improve them with gardens. There was a limit, however, to what could be done to beautify a site with other buildings nearby. But at Higashiyama he was free to do with the landscape what he chose, and his settings for earlier palaces were dwarfed by the scope of his vision when he set about planning the retreat. It would be flawlessly proportioned, and the buildings would be surrounded by magnificent gardens. Best of all, they would have for their background the lovely Higashiyama hills.

Although he had been ineffectual in performing his duties as shogun, Yoshimasa was resolute in carrying out the plans for his retreat. Having decided, for example, that the gardens must contain imposing trees and ornamental rocks, he commanded that suitable trees and rocks be removed from the gardens of the palaces of Kyoto and brought to Higashiyama. It seems not to have bothered him that the residents of the old palaces might not wish to have their gardens plundered. That was not his only problem. With the primitive means available, a great many laborers were needed to move the heavy trees and rocks from the city to the hills. Luckily for Yoshimasa, in 1488 the daimyo of Echizen offered him three thousand laborers, including a thousand of samurai status, to help dig up, move, and replant at Higashiyama trees that had stood in the garden of the retired emperor’s palace.

Construction of the kaisho, begun in 1486, was completed in the following year. Funds for erecting the building had been sought throughout the country, but the response was poor. New taxes, said to be temporary, were imposed on the peasants, who were promised that they would be levied on only one occasion, but in fact, they were repeatedly renewed. Whether the tax demands were directed at the peasants or the landowners, they were most often for corvée labor, needed to erect the buildings.3 In 1485 local samurai (kokujin) and peasants, angered by the incessant demands for their labors, rose in a large-scale revolt that was put down only with difficulty.

Yoshimasa officially opened the kaisho on November 19, 1487. Three days later, he granted audiences to various nobles who had come to congratulate him on its completion. The kaisho, a more impressive building than the tsunenogosho,4 probably stood on the site of the present sand garden of the Ginkaku-ji, surrounded by gardens and looking out over ponds in two directions.

The kaisho was an architectural innovation of the Muromachi period. Originally a part of the private house of a member of the aristocracy or the warrior class, it was used mainly for social gatherings. In 1401 Ashikaga Yoshimitsu built the first kaisho that was a separate building, and from then on each shogun who lived in the Muromachi Palace built his own kaisho. In the days of Yoshimasa’s predecessors, the kaisho sometimes served as the site of conferences between the shogun and his ministers, so often, in fact, that bakufu politics were often referred to as “kaisho politics.”5

Yoshimasa, however, had no intention of using the kaisho at his Higashiyama retreat for political conferences with advisers. He had abdicated as shogun in order to get away from the bickering of politicians. He had hated having to listen to his advisers debate opposing views, but (because he was the shogun) he was obliged to endure the boredom. Now he was a free man. None of the retreat buildings would be used for political or other public purposes; they were variously intended instead as Yoshimasa’s residence, as temple buildings where he would worship, or as rooms where he might indulge in aesthetic pursuits.6

The kaisho, was not, however, intended to be a hermitage where Yoshimasa, renouncing ties with other human beings, gave himself to solitary contemplation of the sorrows of the world. Other buildings at the Higashiyama retreat were suitable for Zen meditation or for recitation of the nenbutsu, but the kaisho provided the pleasure of human company that even a recluse sometimes desires.

Portrait of Ikkyū Sōjun by Bokusai Shōtō, Ikkyū’s appointed successor and the compiler of the official chronology of Ikkyū’s life. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum)

Portrait of Ashikaga Yoshihisa by Kanō Masanobu. (Courtesy Jizō-in)

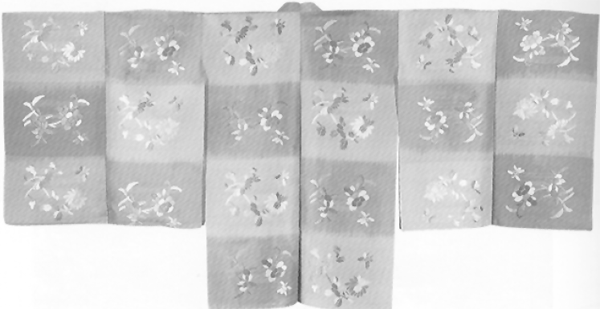

Above. Chōken, a kind of jacket worn by actors in nō plays, especially those that take place in autumn. The pattern shows flowers and insects of the season. Originally a gift from Ashikaga Yoshimasa to a nō actor who had pleased him, the garment has been rewoven in recent times. (Courtesy Kongo School Collection; photograph by Keizō Kaneko)

Below. Interior of the Dōjinsai, a four-and-a-half-mat room where Ashikaga Yoshimasa drank tea with friends. The square pillars, shōji, staggered shelves, writing desk, and tatami-covered floor would become typical of tea ceremony rooms. The garden is an integral part of the room. (Courtesy Jishō-ji, Kyoto)

The Ginkaku, or Silver Pavilion. (Courtesy Jishō-ji, Kyoto; photograph by Akira Nakata)

Yoshimasa invited to the kaisho men like himself who could quietly appreciate paintings and other works of art and who were devoted to such refined activities as the composition of poetry and the formal drinking of tea. Poetry making was probably the main purpose of the kaisho.

Yoshimasa was an accomplished waka poet. He probably first learned how to compose waka as a small boy, as waka composition, along with calligraphy, was a basic part of his education. Like the Heian aristocrats, the military rulers of Japan considered the ability to produce a poem whenever the circumstances required one to be an indispensable social accomplishment. Even though relatively few poems by Yoshimasa have survived, we may assume that during his lifetime he composed a great many.

The poetic style favored by Yoshimasa (and by most poets of his day) was that of the Nijō school. Those who followed the traditions of this school believed that the most important task for a poet when composing waka was to express himself with simplicity and clarity. He also had to observe with great care the rules of waka composition that had evolved over the centuries. Allusion to the poetry of the past was considered to be essential. For this reason, an aspiring waka poet, regardless of his school, had to be thoroughly acquainted with the major anthologies of waka poetry and was expected not only to refer to older poems but also to restrict himself to their vocabulary. At all costs, he had to avoid anything that might make his poems seem ugly, whether because of words that were not in the approved poetic diction or allusions that seemed inappropriate.

Poetry making was essentially a social activity. No doubt many poets polished their verses in the solitude of their quarters, but beginning in the Heian period, members of the court were accustomed to participate in poem competitions known as uta-awase. Two “teams” of poets were required to prepare poems on set topics, and a judge decided which side was the more successful or whether there was a tie. Strict rules of composition were formulated for the uta-awase. Although these rules are apt to seem trivial and even arbitrary, they imparted literary value to what might otherwise have been no more than a game. Without rules, there would have been no objective way of deciding which of two similar waka on a given theme was superior. The judge of an uta-awase had to be a recognized expert, familiar with all the rules; otherwise, his decision on the relative merits of two poems might become an occasion for recriminations. Only a master of the art could be sure that his decisions would be accepted without dispute.

Yoshimasa seems to have enjoyed taking part in uta-awase sessions. It is hard to imagine that any judge would have dared not to award the palm to a waka composed by the shogun, but surviving examples indicate that even without benefit of favoritism, Yoshimasa could have held his own. He was familiar enough with the rules of poetry to avoid committing any obvious fault, and even though his poems are seldom memorable, he took poetry making seriously.

Yoshimasa’s private collection of waka includes a poetic dialogue between him and Asukai Masachika, a poet who often served as a judge of uta-awase. Before quoting a waka by Masachika, Yoshimasa wrote the following headnote:

When I sent Asukai Masamichi one hundred poems I had myself composed and asked him to rate them, he affixed his seal of approval to fifty-two of them, then wrote at the end of the scroll, In reply, Yoshimasa sent a poem in which he declared that his “flowers,” poor things though they were, had come from the heart.7

| momokusa ni | None of the hundred |

| niowanu iro wa | Grasses is without fragrance, |

| nakeredomo | But I gaze with even |

| hana aru wo koso | Greater, unending pleasure |

| nao akazu mireō | On those that bear flowers. |

Yoshimasa’s waka rarely displayed the individuality we might expect of so unusual a man, but his “poems of complaint” (jukkai) are sometimes effective. The following poem suggests dissatisfaction with himself and hints at his difficulty in governing the country:

| ukiyo zo to | “What a sad world it is!” |

| nabete iedomo | Everyone says the same, but |

| osameenu | I’m the only one, |

| wagami hitotsu ni | Unable to control it, |

| nao nageku kana | Whose grief keeps on growing.8 |

Yoshimasa also wrote some poetry in Chinese. The Higashiyama period was one of the high points—perhaps the highest—of the composition of kanshi in Japan.9 Many of the best kanshi were written by Zen monks attached to one of the Five Mountains (gozan), the major Zen monasteries in Kyoto. Yoshimasa had frequent contacts with these monks and undoubtedly knew their poetry and sometimes joined with them in composing kanshi, but he was more interested in waka than in kanshi. After Shotetsu’s death in 1459, there were no outstanding waka poets for Yoshimasa to emulate, but this probably did not disturb him. Poets who occupy only a minor place in the history of waka were important in their day, and Yoshimasa turned to them for comments and praise.

The most important form of Japanese poetry in the Higashiyama culture was undoubtedly renga. During the first centuries of its existence (the oldest example goes back to the eighth century), renga was little more than a test of whether a second poet was clever enough to complete a poem after someone else had composed a puzzling seventeen syllables. The more obscure the opening verse, the greater the achievement of the man who managed to make sense of it in his response. Sometimes, as in the following example, fourteen syllables were followed by seventeen:

| abunaku mo ari | It is frightening |

| medetaku mo ari | But also brings us joy |

| muko iri no | The log bridge |

| yube ni wataru | We cross in the evening |

| hitotsubashi | To welcome the groom.10 |

The first verse presents the elements of a riddle: What is at once dangerous and felicitous? The answer: the members of a family cross a shaky single-log bridge to welcome the young man they will take into their family. The reply to the puzzling first link was clever, but the exchange does not make a satisfactory whole. Renga was still hardly more than a game.

The breakthrough in the creation of renga as a serious poetic art occurred when sequences in more than two links came into fashion at the end of the twelfth century. The “chain renga” (kusari renga), as it was called, developed eventually into a long poem composed by several persons responding by turns to one another’s “links” in accordance with rules evolved by poets at the court. Sensing the literary possibilities of a poetic form that had previously been mainly a display of quick wit, they gave it dignity by providing it with rules.

Nijō Yoshimoto (1320–1388) was the first to write perceptively of the art of the renga. He considered it to be a form of waka, thereby exalting it to the level of a sacred art. The distinctive feature of renga at this time, apart from the fact that a single poem was composed by several poets, was that its language was not restricted to the poetic vocabulary of the imperially sponsored collections. It also could be more contemporary in subject matter, sometimes touching on current situations rather than the eternal themes preferred by waka poets in the bulk of their poems. Minase sangin (Three Poets at Minase), the most famous renga sequence, includes this link by Sōgi, the great master of renga, evoking the misery of Kyoto during the Ōnin War:

| kusaki sae | Even plants and trees |

| furuki miyako no | Share the bitter memories |

| urami ni te | Of the old capital.11 |

The rules of renga multiplied in the attempt to make a game into a refined literary art. Finally, so many rules were created that there was a need for specialists who knew them all, and sessions of renga were presided over by experts who were ready to disqualify a link if it broke even the most obscure rule.

The art of renga reached its height during the late fifteenth century. The two greatest poets of renga—Sōgi (1421–1502) and Shinkei (1406–1475)—were active at this time, and other poets of almost equal distinction took part with them in creating renga sequences in a hundred or even a thousand links. Renga were composed not just by the relatively few masters but by innumerable people all over the country, including illiterates, as we can infer from these remarks by Shinkei:

The renga verses I have heard recently in country districts have none of the earmarks of a disciplined, conscious art. The poets seem to be in a state of complete confusion. Indeed, ever since amateurs have grown so numerous the art of composing noble, deeply felt poetry seems to have come to an end. Renga has become nothing more than a glib chattering, and all mental discipline has vanished without a trace. That is why when one passes along the roads or by the marketplaces one’s ears are assaulted by the sounds of thousand-verse or ten-thousand-verse compositions, and even the rare persons who have real familiarity with the art employ it solely as a means of earning a living. Day after day, night after night, they engage in indiscriminate composition together. Our times would seem to correspond to the age of stultification and final decline of the art.12

Why, one may wonder, was renga so popular in the Higashiyama era? The simplest answer, though it is difficult to prove, is that at a time of warfare and hostilities that separated man from man, renga was popular because it brought people together in convivial circumstances. From this time, there are frequent mentions of friends gathering to eat a simple meal and then enjoying the pleasure of composing renga or waka together. Or the same people might, after drinking saké, sing ballads to dissipate the gloom of their daily lives. In the midst of the violent conflicts of the Ōnin War, people yearned for and found comradeship and peace in such gatherings. As Haga Kōshirō wrote, “Communality was definitely one of the notable characteristics of the Higashiyama culture.13

Renga was ideal entertainment for a small group of friends who gathered in an evening in what may have seemed like an island of peace and goodwill, the spiritual refuge of each. By its very nature, a renga session was not a suitable place for controversy. A clash of political views or of economic interests would fatally impair the harmony necessary for men who gathered to create renga together. In the interests of harmony, certain subjects were banned from the conversation at these gatherings, including discussions of politics or religion, mention of household matters, and criticism of other people.14

Unlike the uta-awase, which pitted one poet against another, each competing for recognition as superior to the other, renga was a cooperative effort. It was rather like the ancient kemari (kickball), a game in which the players do not attempt to kick the ball so far that no one can retrieve it or to kick it into a net in order to win a point. Instead, they help one other in keeping the ball from falling to the ground; there is no competition and no winner. The same is true of renga. A participant in a renga session who tried to prove that he was better at composing renga than anybody else, in this way destroying the unity of mood that the other poets were trying to create, would not be invited to another session.

The participants often thought of themselves as belonging to a za, a group of people who shared a communality of spirit. This did not necessarily involve any loss of individuality by the members of the za, though it is true that nobody deliberately tried to be unlike the others. Nijō Yoshimoto compared renga with nō, another art perpetuated by a za. The nō actors who perform a play belong to the same za and are accustomed to working with and supporting one another, but this does not include suppressing their individual characteristics as actors. The ideal members of a renga session were men who knew one another well and could respond easily to one another’s poems but who never merely echoed.

The art of renga was so highly esteemed that some thought it partook of the divine. In 1471 a hokku (the opening verse of a renga sequence) offered by Sōgi to the Mishima Shrine in Izu was credited with effecting the miraculous cure of a child. And in 1504 Sōgi’s disciple Sōchō offered at the same shrine a renga sequence in a thousand links by way of prayer for the victory in battle of the daimyo he served.

No doubt participants in the renga sequences composed by amateurs in the countryside, the kind of poets for whom Shinkei displayed contempt, sometimes forgot the spirit of joint composition and contributed a verse that brought momentary applause, even if it broke the rules. The kind of renga practiced by Sogi, Shinkei, and their peers was too lofty for average amateurs to approximate, but amateurs were just as eager as the masters to take part in renga, crude though their compositions might be.

It is not surprising that Shinkei, a consecrated poet of renga, should have looked with disdain on ignorant merchants and farmers who thought they were composing renga. But however much contempt renga masters might express in their writings for would-be poets who did not understand the higher reaches of the art, not even they could be wholly free of worldly concerns. The disorder and destruction during the Ōnin War caused many renga poets to flee the capital and look for patrons elsewhere. Daimyos and other rich men in remote parts of the country, eager to become proficient in composing the kind of poetry most in vogue in the capital, gladly offered renga masters hospitality in return for receiving guidance in composing renga.

Composing renga in the style of Sōgi was exhausting for daimyos, who were primarily fighting men and not poets. However eager they may have been to become proficient in the serious renga, they must have breathed a sigh of relief when the serious session ended and refreshments were served. Then the participants could unbend and indulge themselves in comic, or even ribald, renga sequences.

Ashikaga Yoshimasa was devoted to renga composition. Early in his reign as shogun, he sponsored an annual renga session in a thousand links at the Kitano Shrine, and on numerous other occasions he joined guests in composing renga. In the spring of 1465, when he was in his thirtieth year, he visited various sites in the city famed for their cherry blossoms, then at their height. Afterward, a renga session was held at Kachōyama, one of the Higashiyama hills.15 Of course, Yoshimasa was asked to compose the hokku, considered to be the most important. He wrote:

| sakimichite | Flowers in full bloom— |

| hana yori hoka no | But apart from the blossoms, |

| iro mo nashi | No color anywhere. |

Two days later, on an excursion to Oharano, he composed the hokku at another renga gathering:

| tōku kite | It was worth having |

| miru kai ari ya | Come from afar to behold |

| sakurabana | Cherries in full bloom |

These hokku convey Yoshimasa’s pleasure on seeing the masses of cherry blossoms. Perhaps the former implies that there was little to cheer one’s eyes apart from the blossoms, but this was a relatively happy year for Yoshimasa. When he went to see the blossoms at Kachōyama, he was accompanied by his wife, Hino Tomiko, who would give birth in the eleventh month of that year to his first son, Yoshihisa. In the eighth month, Yoshimasa went to Higashiyama, perhaps already thinking of building a retreat there.

When Yoshimasa decided to build the kaisho at his mountain retreat, he probably was anticipating the pleasure of composing renga with friends in those surroundings. The gardens and hills visible from the kaisho would provide inspiration for the poetry. At some point in the gathering, food and drink would be served, strengthening the feeling of belonging to a za of like-minded friends. Even the most skillful who participated in the session of renga probably did not consider themselves to be the equals of Sogi or Shinkei, and that may be why none of the texts of the poems composed on such occasions survive. The “links” of the renga sequence may have been written down by a scribe, in the manner of the sessions of professional renga poets, but the manuscripts seem not to have been treasured. The participants were probably pleased to think of themselves as amateurs, gentlemen of leisure who composed verses as a pleasure shared with intimates; they had no ambition of creating immortal poetry. In this sense, these men were the prototypes of the bunjin, the gentlemen-poets of the Edo period, an ideal for which the original inspiration came from China.

It is not clear which guests Yoshimasa invited to the kaisho to enjoy one another’s company and to share the pleasure of composing poetry, casually sketching, and drinking saké or tea together. Probably they included nobles and cultivated members of the military class but not Zen priests from the Kyoto monasteries, even though Yoshimasa enjoyed a friendly association with them. As Haga Kōshirō wrote, “The Zen priests were extremely skillful at composing linked verse in Chinese, but they were completely uninterested in composing renga; I have yet to find an example from a reliable source of a Zen priest who composed renga.”16

Yoshimasa worshiped Chinese culture, as we know from his collection of paintings and other works of art. He read not only those Chinese classics that were known to every educated Japanese of the time but less familiar works as well that he ordered from China. Reading even fairly difficult texts in Chinese was probably no problem for Yoshimasa. Chinese was probably as familiar to him as Latin was to the European intellectuals who, over centuries, composed both poetry and scientific treatises in Latin and assumed that every educated person would be able to read them. But however competent the Japanese might become in composing poems in Chinese, they could not totally forsake the customs of their own country. I find it difficult, for example, to imagine Yoshimasa and his friends seated on chairs (as Chinese would have done) while they composed renga. Also, the topics of Yoshimasa’s waka were unmistakably Japanese, in the tradition of the Heian poets, and seldom borrowed from Chinese poetry. Although his poems do not rank as masterpieces, the language reveals, as in this waka on plovers (chidori), how sensitive Yoshimasa was to the music of Japanese:

| tsuki nokoru | How the plovers rise up |

| urawa no nami no | When they see the vestiges |

| shinonome ni | Of the moon lingering |

| omokage miete | At the break of day |

| tatsu chidori kana | In the waves off the shore.17 |