Chapter Two

The Norman Era, 1066–1154

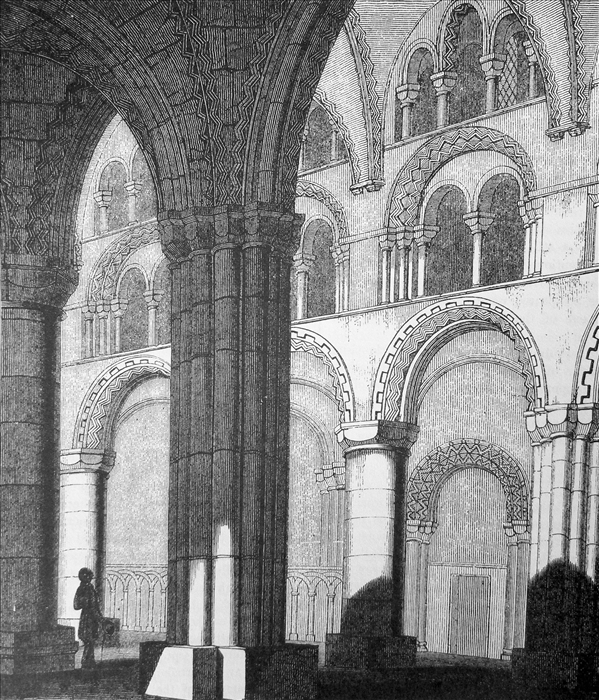

Fig. 7. The Nave of Durham Cathedral. Begun in the late eleventh century, the Romanesque cathedral at Durham remains a dramatic statement of Norman power.

19. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle on the Norman Conquest

From the late ninth century into the twelfth, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle provides a contemporary record of events in England, updated annually by monks whose identities are unknown to us. The excerpt below tells the story, some of it in alliterative verse (i.e., verse in which common sounds are frequently repeated at the beginnings of words), of the momentous Norman Conquest, from the perspective of the conquered. This version was written at Peterborough Abbey in eastern England. The “hides” referred to in the entry for 1085 are measures of land, but the size of a hide could vary from roughly 60 to 120 acres.

Source: trans. J. Ingram, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1912), pp. 144–54, 162–68; revised.

[A.D. 1065] . . . About midwinter [25 December] King Edward came to Westminster, and had the minster [church] there consecrated, which he had himself built to the honor of God, and Saint Peter, and all God’s saints. This church-hallowing was on Childermas day [28 December]. He died on the eve of twelfth-day [5 January]; and he was buried on twelfth-day in the same minster; as it is hereafter said.

Here Edward king,

of Angles lord,

sent his steadfast

soul to Christ.

In the kingdom of God

a holy spirit!

He in the world here

abode awhile,

in the kingly throng

of council sage.

Four and twenty

winters wielding

the scepter freely,

wealth he dispensed.

In the tide of health,

the youthful monarch,

offspring of Æthelred!

ruled well his subjects;

the Welsh and the Scots,

and the Britons also,

Angles and Saxons—

relations of old.

So apprehend

the first in rank,

that to Edward all

—the noble king—

were firmly held

high-seated men.

Blithe-minded, aye,

was the harmless king;

though he long ere,

of land bereft,

abode in exile

wide on the earth;

when Cnut overcame

the kin of Ethelred,

and the Danes wielded

the dear kingdom

of Engle-land.

Eight and twenty

winters’ rounds

they wealth dispensed.

Then came forth

free in his chambers,

in royal array,

good, pure, and mild,

Edward the noble;

by his country defended—

by land and people.

Until suddenly came

the bitter Death

and this king so dear

snatched from the earth.

Angels carried

his soul sincere

into the light of heaven.

But the prudent king

had settled the realm

on high-born men—

on Harold himself,

the noble earl;

who in every season

faithfully heard

and obeyed his lord,

in word and deed;

nor gave to any

what might be wanted

by the nation’s king.

This year also was Earl Harold consecrated as king; but he enjoyed little peace while he ruled the kingdom.

A.D. 1066. This year King Harold came from York to Westminster, on the Easter after the midwinter when the king (Edward) died. Easter was then on the sixteenth day before the calends of May [16 April]. Then over all England such a sign was seen as no man ever saw before. Some men said that it was the comet-star, which others call the long-haired star. It appeared first on the eve called Litania major, that is, on the eighth before the calends of May [25 April]; and so it shone all the week. Soon after this Earl Tostig came in from beyond the sea into the Isle of Wight, with as large a fleet as he could get; and he was there supplied with money and provisions. From there he proceeded, and committed outrages everywhere by the seacoast where he could land, until he came to Sandwich. When King Harold, who was in London, was told that his brother Tostig had come to Sandwich, he gathered so large a force, both naval and military, as no king before collected in this land; for it was credibly reported that Earl William from Normandy, King Edward’s cousin, would come here and gain this land; just as afterward happened. When Tostig understood that King Harold was on the way to Sandwich, he departed from there, and took some of the boatmen with him, . . . and went north into the Humber with sixty ships; from there he plundered in Lindsey, and there slew many good men. When the Earls Edwin and Morcar understood that, they came here, and drove him from the land. And the boatmen forsook him. Then he went to Scotland with twelve smacks [single-masted boats]; and the king of the Scots entertained him, and aided him with provisions; and he lived there all the summer. There Harald, king of Norway, met him with three hundred ships. And Tostig submitted to Harald, and became his man.

Then came King Harold [of England] to Sandwich, where he awaited his fleet; for it was long before it could be collected: but when it was assembled, he went into the Isle of Wight, and there lay all the summer and the autumn. There was also a land force everywhere by the sea, though it was worth nothing in the end. It was now the nativity of Saint Mary [8 September], when the provisioning of the men began; and no man could keep them there any longer. They therefore had leave to go home: and the king rode up, and the ships were driven to London; but many perished before they came there. When the ships had come home, then came Harald, king of Norway, north into the Tyne, unexpectedly, with a very great sea-force—no small one; with perhaps three hundred ships or more; and Earl Tostig came to him with all those that he had got; just as they had before said: and they both then went up with all the fleet along the River Ouse toward York.

When King Harold was told in the south, after he had come from the ships, that Harald, King of Norway, and Earl Tostig had come up near York, then he went northward by day and night, as soon as he could collect his army. But, before King Harold could get there, the Earls Edwin [of Mercia] and Morcar [of Northumbria] had gathered from their earldoms as great a force as they could get, and fought the enemy. They made a great slaughter, too; but there was a good number of the English people slain, and drowned, and put to flight, and the [invading] Northmen had possession of the field of battle. It was then told Harold, king of the English, that this had thus happened. And this fight was on the eve of Saint Matthew the apostle, which was Wednesday [20 September]. Then after the fight Harald, king of Norway, and Earl Tostig went into York with as many followers as they thought fit; and having procured hostages and provisions from the city, they proceeded to their ships, and proclaimed full friendship, on condition that all would go southward with them, and gain this land. In the midst of this came Harold, king of the English, with all his army, on the Sunday, to Tadcaster; where he collected his fleet. From there he proceeded on Monday throughout York. But Harald, king of Norway, and Earl Tostig, with their forces, had gone from their ships beyond York to Stamford Bridge, because it was given them to understand that hostages would be brought to them there from all over the shire. There Harold, king of the English, came unexpectedly against them beyond the bridge; and they clashed together there, and continued long in the day fighting very severely. There were slain Harald, king of Norway, and Earl Tostig, and a multitude of people with them, both of Norwegians and English; and the Norwegians that were left fled from the English, who slew them hotly behind; until some reached their ships, some were drowned, some burned to death, and thus variously destroyed, so that there were few left, and the English gained possession of the field. But there was one of the Norwegians who withstood the English, so that they could not pass over the bridge, nor complete the victory. An Englishman aimed at him with a javelin, but it achieved nothing. Then came another under the bridge, who pierced him terribly under the coat of mail. And Harold, king of the English, then came over the bridge, followed by his army; and there they made a great slaughter, both of the Norwegians and of the Flemings. But Harold let the king’s son, Edmund, go home to Norway with all the ships. He also spared Olaf, the Norwegian king’s son, and their bishop, and the earl of the Orkneys, and all those that were left in the ships, who then went up to our king and took oaths that they would ever maintain faith and friendship with this land. Whereupon the king let them go home with twenty-four ships. These two general battles were fought within five nights.

Meantime Earl William came up from Normandy into Pevensey on the eve of Saint Michael’s mass [28 September], and soon after his landing was complete, [he and his Normans] constructed a castle at the port of Hastings. This news was then told to King Harold; and he gathered a large force and came to meet him at the estuary of Appledore. William, however, came against him by surprise, before King Harold’s army was collected; but the king, nevertheless, fought very hard against him with the men that would support him, and there was a great slaughter on either side. There were slain King Harold, and Leofwin his brother, and Earl Girth his brother, with many good men: and the Frenchmen gained the field of battle, as God granted them for the sins of the nation. Archbishop Aldred and the corporation of London then wanted to have the child Edgar as king, as he was quite familiar to them; and Edwin and Morcar promised them that they would fight with them. But the more quickly things were done, the worse they were done; and so in the end it turned out. This battle was fought on the day of Pope Calixtus [14 October], and Earl William returned to Hastings and waited there to know whether the [English] people would submit to him. But when he found that they would not come to him, he went up with all his force that was left and that came to him from over sea since the battle, and ravaged all the country that he overran, until he came to Berkhampstead, where Archbishop Aldred came to meet him, with the child Edgar, and Earls Edwin and Morcar, and all the best men from London, who submitted then because they had no choice, although the most harm had already been done. It was very ill-advised that they did not so before, seeing that God would not improve things for our sins. And the English leaders gave William hostages and took oaths: and William promised them that he would be a faithful lord to them; though in the midst of this the Normans plundered wherever they went.

Then on midwinter’s day [25 December] Archbishop Aldred consecrated William as king at Westminster, and gave him possession [of the kingdom] with the books of Christ, and also had him swear, before he would set the crown on his head, that he would govern this nation as well as any before him best did, if the English would be faithful to him. Nevertheless William laid very heavy tribute on men, and in Lent he went over sea to Normandy, taking with him Archbishop Stigand, and Abbot Aylnoth of Glastonbury, and the child Edgar, and the Earls Edwin, Morcar, and Waltheof, and many other good men of England. Bishop Odo and Earl William lived here afterward, and built castles widely through this country, and harassed the miserable people, and ever since then evil has increased very much. May the end be good, when God wills! . . .

A.D. 1067. This year the king came back again to England on Saint Nicholas’s day [6 December]; and on the same day the church of Christ at Canterbury was burned. Bishop Wulfwy also died, and is buried at his see in Dorchester. The child Edric and the Welsh were unsettled this year, and fought with the castlemen at Hereford, and did them much harm. The king this year imposed a heavy geld [tax] on the wretched people, but, notwithstanding, let his men always plunder all the country that they went over, and then he marched to Devonshire, and besieged the city of Exeter for eighteen days. Many of his army were slain there, but he had promised them well, and performed ill, and the citizens surrendered the city because the thegns [English nobles] had betrayed them. . . . This year Githa, Harold’s mother, and the wives of many good men with her, went out to the Flat-Holm, and stayed there some time, and so departed from there over the sea to Saint-Omer. This Easter the king came to Winchester. . . . Soon after this [King William’s wife] the Lady Matilda came here to this land; and Archbishop Aldred consecrated her as queen at Westminster on Whit Sunday [27 May].

Then the king was told that the people in the north had gathered themselves together and would stand against him if he came. Whereupon he went to Nottingham, and built there a castle, and so advanced to York, and there built two castles, and did the same at Lincoln, and everywhere in that region. Then Earl Gospatric and the best [English] men went into Scotland. Amidst this one of Harold’s sons came from Ireland with a naval force into the mouth of the River Avon unexpectedly, and soon plundered over all that region; from there they went to Bristol, and would have stormed the town, but the people bravely withstood them. When they could gain nothing from the town, they went to their ships with the booty which they had acquired by plunder; and then they advanced upon Somersetshire, and landed there; Ednoth, [the king’s] master of the horse, fought with them, but he was slain there, as were many good men on either side, and those that survived departed.

A.D. 1068. This year King William gave Earl Robert the earldom over Northumberland; but the local English attacked him in the town of Durham, and slew him, and nine hundred men with him. Soon afterward Edgar Etheling came with all the Northumbrians to York; and the townsmen made a treaty with him. But King William came from the south by surprise against them with a large army, and put them to flight, and slew on the spot those who could not escape, which were many hundred men, and plundered the town. He desecrated Saint Peter’s minster, and he also despoiled and trampled upon all other places; and the etheling [prince] went back again to Scotland. After this Harold’s sons came from Ireland, about midsummer [24 June], with sixty-four ships into the mouth of the River Taft, where they stealthily landed. Earl Breon came suddenly against them with a large army, and fought with them, and slew there all the best men that were in the fleet; and the others, being small forces, escaped to the ships, and Harold’s sons went back to Ireland again.

A.D. 1069. This year Aldred, archbishop of York died; and he is buried there, at his see. He died on the day of Protus and Hyacinthus [11 September], having held the see with much dignity ten years minus only fifteen weeks. Soon after this three of the sons of King Swein came from Denmark with two hundred and forty ships, together with Earl Esborn and Earl Thurkill, into the River Humber; where they were met by the child Edgar, and Earl Waltheof, and Merle-Sweyne, and Earl Gospatric with the Northumbrians, and all the local English; riding and marching in good spirits with an immense army: and so they all unanimously advanced to York, where they stormed and demolished the castle, and won innumerable treasures. They slew there many hundreds of Frenchmen [the Normans], and led many with them to the ships, but, before the shipmen came there, the Frenchmen had burned the city and entirely plundered the holy minster of Saint Peter and destroyed it with fire. When the king heard this, then he went northward with all the forces that he could collect, despoiling and laying waste the shire everywhere, while the [Danish] fleet lay all the winter in the River Humber, where the king could not come at them. The king was in York on Christmas Day, and so all the winter on land, and came to Winchester at Easter. Bishop Egelric, who was at Peterborough, was betrayed this year, and was led to Westminster; and his brother Egelwine was outlawed. This year also Brand, abbot of Peterborough, died on the fifth before the calends of December [27 November].

A.D. 1070. This year Lanfranc, who was abbot of Caen, came to England; and after a few days he became archbishop of Canterbury. He was invested [officially made archbishop] on the fourth before the calends of September [29 August] in his own see by eight bishops, his suffragans [subordinate bishops]. The other bishops who were not there declared by messenger and by letter why they could not be there. The same year Thomas, who was chosen archbishop of York, came to Canterbury, to be invested there after the ancient custom. But when Lanfranc asked for confirmation of Thomas’s obedience with an oath, Thomas refused, and said that he did not owe an oath of obedience. Whereupon Archbishop Lanfranc was angry, and ordered the bishops, who had come there by Archbishop Lanfranc’s command to do the service, and all the monks to unrobe themselves [to take off the vestments they had put on for Thomas’s investment ceremony]. And they did so at his order. Therefore Thomas departed without consecration for the time being. Soon after this, it happened that Archbishop Lanfranc went to Rome, and Thomas accompanied him. When they arrived there, and had spoken about other things concerning which they wished to speak, then Thomas began his speech: how he came to Canterbury, and how the archbishop required obedience from him with an oath, but he declined it. Then began Archbishop Lanfranc to show with clear distinction, that what he asked he asked by right; and with strong arguments he confirmed the same before Pope Alexander, and before all the council that was collected there; and so they went home. After this Thomas came to Canterbury, and humbly fulfilled all that the archbishop required of him, and afterward received consecration. . . .

A.D. 1085. In this year men reported, and truthfully asserted, that Cnut, king of Denmark, son of King Swein, was coming in this direction, and was resolved to win this land with the assistance of Robert, earl of Flanders; for Cnut had married Robert’s daughter. When William, king of England, who was then resident in Normandy (for he ruled both England and Normandy), understood this, he went into England with so large an army of mounted troops and footsoldiers from France and Brittany as never before sought this land, so that men wondered how this land could feed all that force. But the king left the army to shift for themselves through all this land among his subjects, who fed them, each according to his quota of land. Men suffered much distress this year, and the king caused the land to be laid waste about the seacoast, so that, if his foes landed, they would not have anything on which they could very readily seize. But when the king truly understood that his foes were impeded, and could not further their expedition, then he let some of his army go home to their own land; but some he held in England over the winter.

Then, at midwinter, the king was in Gloucester with his council, and held his court there for five days. And afterward the archbishop and clergy held a synod for three days. There Mauritius was chosen bishop of London, William bishop of Norfolk, and Robert bishop of Cheshire. These were all the king’s clerks. After this the king had a large meeting, and very deep consultation with his council, about this land—how it was occupied and by what sort of men. Then he sent his men over all England into each shire, commissioning them to find out how many hundreds of hides were in the shire, what land the king himself had, and what livestock upon the land, or what income he ought to have annually from the shire. Also he commissioned them to record in writing, how much land his archbishops had, and his diocesan bishops, and his abbots, and his earls; and though I may be prolix and tedious, [he also wanted to know] what or how much each man had, who was an occupier of land in England, either in land or in livestock, and how much money it was worth. So very specifically, indeed, did he order them to trace it out, that there was not one single hide, nor a yard of land, no, moreover (it is shameful to tell, though he thought it no shame to do it), not even an ox, nor a cow, nor a swine was left, that was not set down in his record. And all the written particulars were afterward brought to him.

A.D. 1086. This year the king wore his crown and held his court in Winchester at Easter, and he so arranged it that he was at Westminster by Pentecost [24 May], and dubbed his son Henry a knight there. Afterward he moved about so that he came to Salisbury by Lammas [1 August], where he was met by his councilors; there all the local English that were of any importance over all England became this man’s [King William’s] vassals, . . . and they all bowed before him, and became his men, and swore him oaths of allegiance that they would be faithful to him against all other men. From there he proceeded into the Isle of Wight, because he wished to go into Normandy, and so he afterward did, though first, according to his custom, he collected a very large sum from his people, wherever he could make any demand, whether with justice or otherwise. Then he went into Normandy, and Edgar Etheling, the relation of King Edward, revolted against him, for he received not much honor from him; but may the almighty God give him honor hereafter. And Christina, the sister of [Edgar] the etheling, went into the monastery of Romsey, and received the holy veil. And the same year there was a very heavy season, and a troublesome and sorrowful year in England, in murrain of cattle, and corn and fruits did not grow, and so much trouble in the weather, as you might not believe; so tremendous was the thunder and lightning, that it killed many men; and it continually grew worse and worse for men. May almighty God improve things whenever he wills it.

A.D. 1087. 1087 winters after the birth of our Lord and Savior Christ, in the twenty-first year after William began to govern and direct England, as God granted him, there was a very heavy and pestilent season in this land. Such a sickness came on men, that nearly every other man had the worst disorder, that is, diarrhea, and that so dreadfully, that many men died from the disorder. Afterward, through the badness of the weather as we mentioned before, such a great famine came over all England that many hundreds of men died a miserable death through hunger. Alas! how wretched and how rueful a time it was! When the poor wretches lay nearly driven to death prematurely, and afterward came sharp hunger and dispatched them altogether! Who will not be full of grief at such a season? Or who is so hardhearted as not to weep at such misfortune? Yet such things happen for folks’ sins, because they will not love God and righteousness. So it was in those days, that little righteousness was in this land with any men except the monks alone, wherever they lived well. The king and the head-men were far too greedy for gold and silver and did not care how sinfully it was acquired, provided it came to them. The king leased out his land at as high a rate as he possibly could; then came some other person, and offered more than the first one gave, and the king leased it out to the man who offered him more. Then came the third, and offered yet more; and the king handed it over to the man that offered him most of all. And he cared not how very sinfully the stewards got it from wretched men, nor how many unlawful deeds they did; but the more men spoke about right law, the more unlawfully they acted. They exacted unjust tolls, and they did many other unjust things that are difficult to reckon.

Also in the same year, before harvest, the holy minster of Saint Paul, the episcopal see in London, was completely burned, with many other minsters, and the greatest and richest part of the whole city. So also, about the same time, almost every major port in all England was entirely burned. Alas! rueful and woeful was the fate of the year that brought forth so many misfortunes.

In the same year also, before the Assumption of Saint Mary [15 August], King William went from Normandy into France with an army, and made war upon his own lord Philip, the king [of France], and slew many of his men, and burned the town of Mantes, and all the holy minsters that were in the town; and two holy men that served God, leading the life of anchorites, were burned therein. This being thus done, King William returned to Normandy. Rueful was the thing he did, but a more rueful befell him. How was it more rueful? He fell sick, and it dreadfully ailed him. What shall I say? Sharp death, which passes by neither rich men nor poor, seized him also. He died in Normandy, on the day after the nativity of Saint Mary [9 September], and was buried at Caen in Saint Stephen’s minster, which he had formerly built, and afterward endowed with manifold gifts. Alas! how false and how uncertain is this world’s wealth! He who was before a rich king, and lord of many lands, had not then of all his land more than a space of seven feet! And he that was formerly clothed in gold and gems, lay there covered with mold! He left behind three sons: the eldest, called Robert, who was earl in Normandy after him; the second, called William, who wore the crown after him in England; and the third, called Henry, to whom his father bequeathed immense treasure.

If any person wishes to know what kind of man [William] was, or what honor he had, or of how many lands he was lord, then will we write about him as well as we understand him: we who often looked upon him, and lived sometime in his court. This King William that we speak about was a very wise man, and very rich, more splendid and powerful than any of his predecessors. He was mild to the good men that loved God, and severe beyond all measure to the men who opposed his will. On that same spot where God granted him that he should gain England, he built a mighty minster [Battle Abbey], and set monks in it, and well endowed it. In his days the great monastery in Canterbury was built, and also very many others over all England. This land was moreover well filled with monks, who modeled their lives after the rule of Saint Benedict. . . . He was also very dignified. He wore his crown three times each year, as often as he was in England. At Easter he wore it in Winchester, at Pentecost in Westminster, at midwinter in Gloucester. And then all the rich men from over all England were with him, archbishops and diocesan bishops, abbots and earls, thegns and knights. So very stern was he also and hot-tempered, that no man dared do anything against his will. He took into custody earls who acted against his will. Bishops he hurled from their bishoprics, and abbots from their abbacies, and thegns into prison. Eventually he did not spare even his own brother Odo, who was a very rich bishop in Normandy. Odo’s episcopal stall was at Bayeux, and he was the foremost man of all to glorify the king. He had an earldom in England, and when the king was in Normandy, then was Odo the mightiest man in England. William confined Odo in prison. But among other things we must not forget the good peace that he made in this land, so that a man of any account might go over his kingdom unhurt with his bosom full of gold [carrying a bag of gold inside his shirt]. No man dared slay another, no matter how much evil he had done to the other; and if any peasant had sex with a woman against her will, he soon lost the limb that he played with. He truly reigned over England, and by his authority so thoroughly surveyed it, that there was not a hide of land in England that he knew not who had it, or what it was worth, and afterward set it down in his book. The land of the Welsh was in his power, and he built castles there, and ruled Anglesey altogether. So also he subdued Scotland by his great strength. As to Normandy, that was his native land, but he also reigned over the earldom called Maine, and if he had yet lived two years more, he would have won Ireland by his valor, and without any weapons.

Assuredly in his time men had much distress, and very many sorrows. He let men build castles and miserably oppress the poor. The king himself was so very rigid and extorted from his subjects many marks of gold and so many hundred pounds of silver, which he took from his people for little need, by right and by unright. He fell into covetousness, and he loved greediness excessively. He made many deer-parks, and he established laws for them, so that whoever slew a hart or a hind [a male or female deer] should be deprived of his eyesight. As he forbade men to kill the harts, so also the boars, and he loved the tall deer as if he were their father. Likewise he decreed that the hares should go free. His rich men bemoaned it, and the poor men shuddered at it. But he was so stern that he did not care about the hatred of them all, for they must follow the king’s will entirely, if they would live, or have land or possessions or even his peace. Alas! that any man should presume so to puff himself up, and boast over all men. May the Almighty God show mercy to his soul, and grant him forgiveness of his sins! These things have we written concerning him, both good and evil that men may choose the good after their goodness, and flee from the evil altogether, and follow the way that leads us to the kingdom of heaven. . . .

Questions: How does the author present Kings Edward, Harold, and William? How did the Norman Conquest affect England, according to this source? Are there any indications of the author’s political sympathies? What events other than national political ones are of interest to the chronicler, and why? What impact did national events have locally?

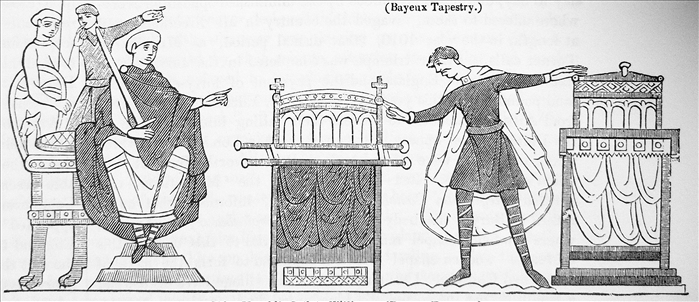

20. The Text of the Bayeux Tapestry

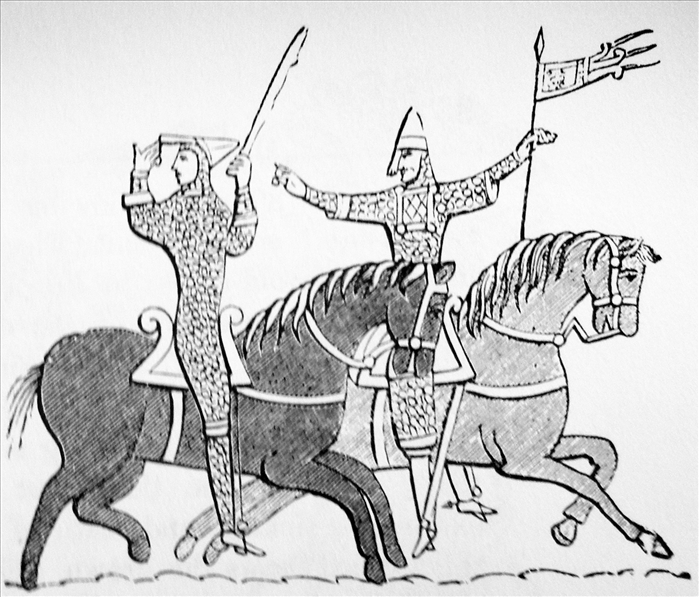

The Bayeux Tapestry, a unique pictorial narrative, is a series of scenes embroidered on linen with a running Latin commentary above. Although we do not know who designed or executed the embroidery, historians think it was created sometime in the last third of the eleventh century, perhaps at, or in association with, the monastery of Saint Augustine in Canterbury. It presents a Norman version of the story of King Harold and William the Conqueror. The entire text, and some of the scenes, are reproduced here.

Source: trans. E. Amt from The Bayeux Tapestry, ed. D.M. Wilson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), plates 1–73.

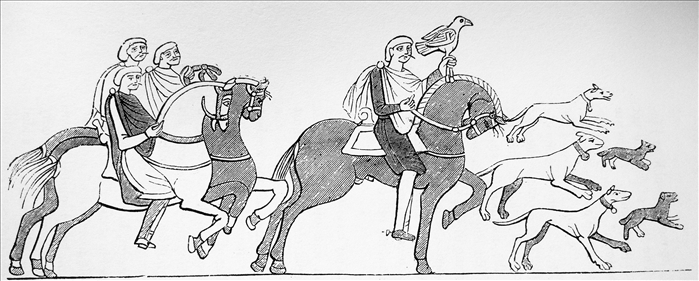

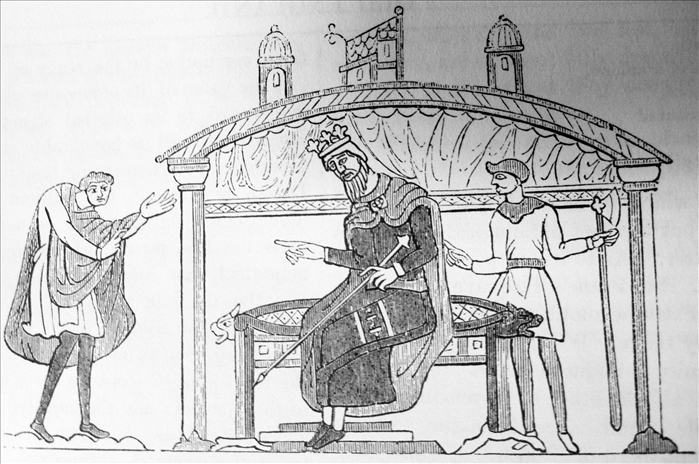

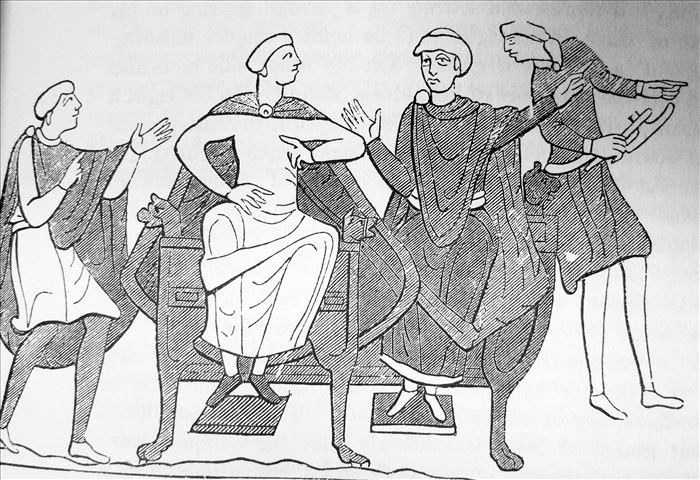

King Edward ( figure 8). Where Harold, duke of the English, and his knights are riding to Bosham church ( figure 9). Where Harold sails the sea ( figure 10) and, with sails full of wind, comes to the land of Count Guy [of Ponthieu]. [Here is] Harold. Where Guy is arresting Harold and has led him to Beaurain and has held him there. Where Harold and Guy are conversing.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10.

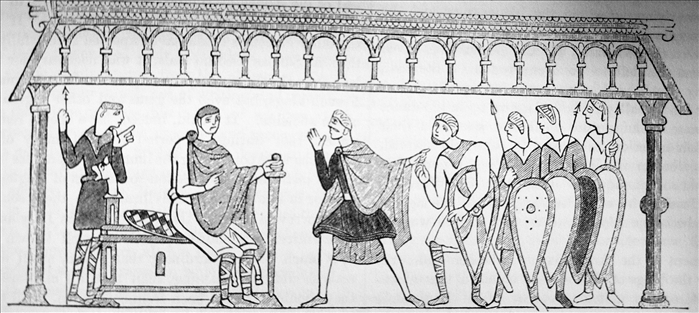

Here Duke William’s messengers have come to Guy. Turold. William’s messengers. Here a messenger has come to Duke William. Here Guy has brought Harold to William, duke of the Normans. Here Duke William has come to his palace with Harold ( figure 11). Here [is] a certain clerk and Ælfgyva. Here Duke William and his army have come to Mont-Saint-Michel. And here they have crossed the River Couesnon. Here Duke Harold has pulled them out of the sands. And they have come to Dol [to attack Duke Conan of Brittany], and Conan turns and flees. Rennes. Here Duke William’s knights are fighting against Dinan, and Conan has offered them the keys. Here William has given Harold arms. Here William comes to Bayeux, where Harold takes an oath to Duke William ( figure 12).

Fig. 11.

Fig. 12.

Fig. 13.

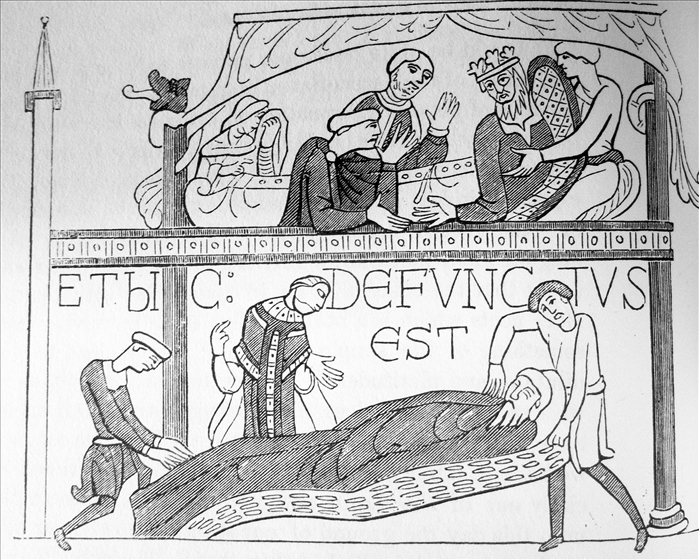

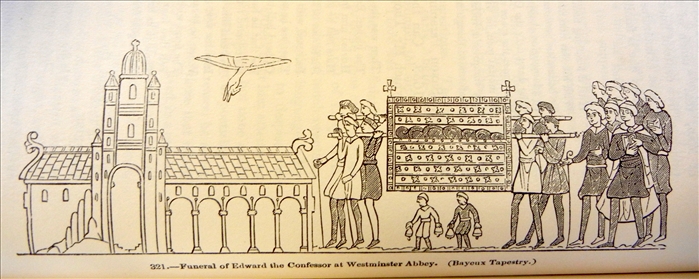

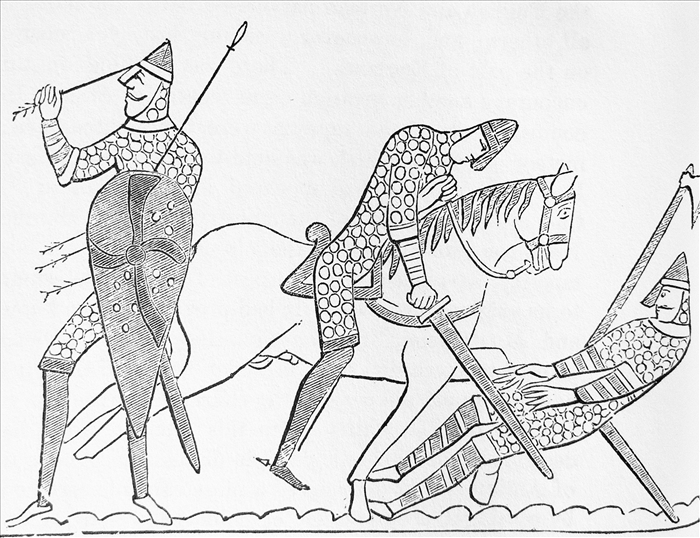

Here Duke Harold has returned to the land of England and comes to King Edward ( figure 13). Here King Edward, on his deathbed, addresses his trusty friends. And here he has died ( figure 14). Here the body of King Edward is carried to the church of Saint Peter the apostle [Westminster Abbey] (figure 15). Here they have given the king’s crown to Harold.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 15.

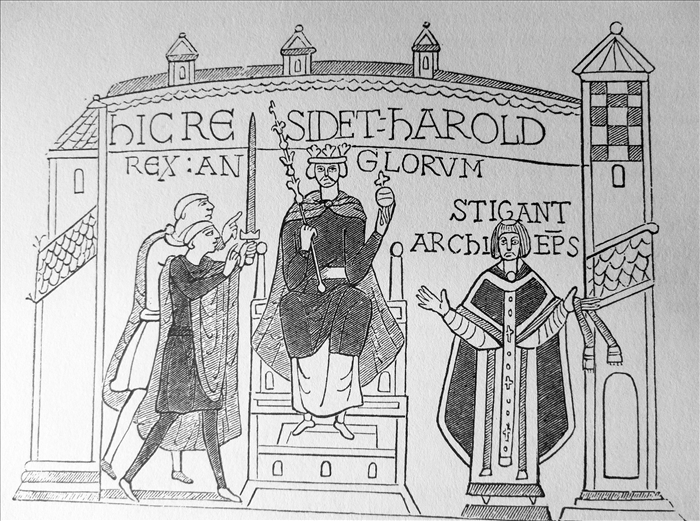

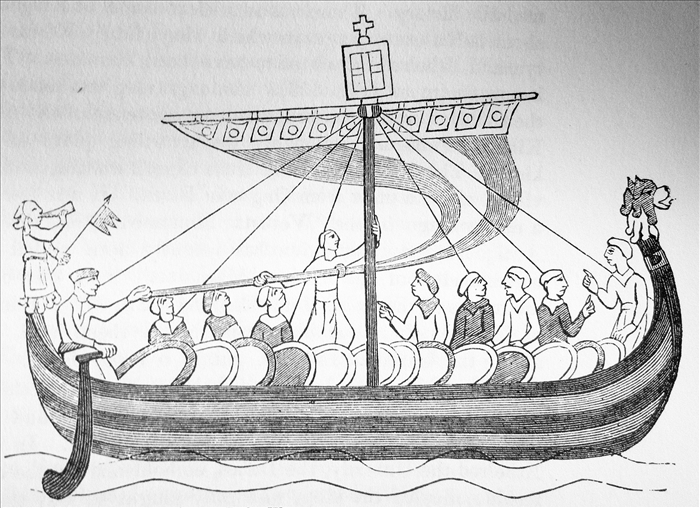

Here sits Harold, king of the English (figure 16). (Archbishop Stigand.) These men are marveling at the star [Halley’s Comet]. [Here is] Harold. Here an English ship comes to the land of Duke William. Here Duke William has ordered ships to be built (figure 17).

Fig. 16.

Fig. 17.

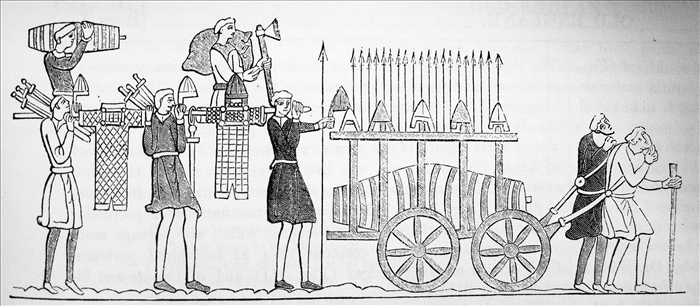

Here they are dragging the ships to the sea. These men are carrying arms to the ships. And here they are pulling a cart with wine and arms ( figure 18). Here Duke William, in a great ship, has crossed the sea and comes to Pevensey ( figure 19).

Fig. 18.

Fig. 19.

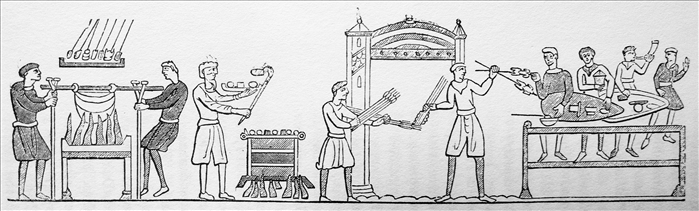

Fig. 20.

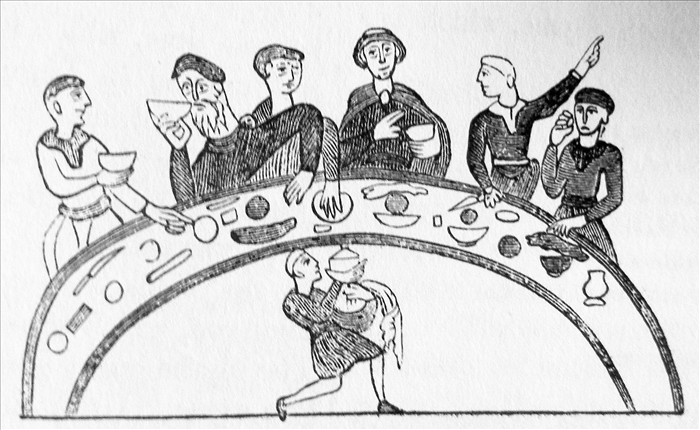

Here the horses are getting out of the ships. And here the knights hurry to Hastings to seize supplies. Here is Wadard. Here meat is being cooked. And here the servants have been preparing, and here they have served, the midday meal ( figure 20). And here the bishop [William’s brother Odo, bishop of Bayeux] blesses the food and drink ( figure 21). [Here is] Bishop Odo. [Here is] William. [Here is] Robert. This man has ordered that a castle be constructed at Hastings. Here reports about Harold have been brought to William. Here a house is being burned.

Fig. 21.

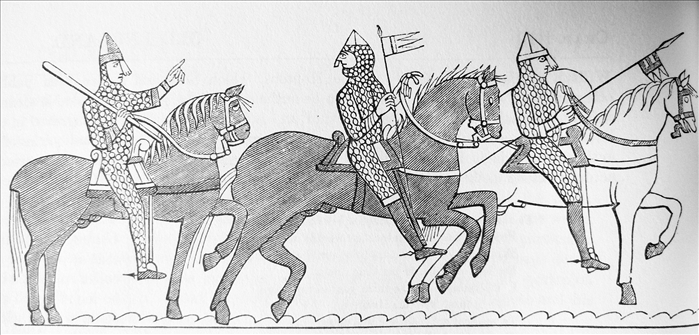

Here the knights have left Hastings and have come to the battle against King Harold. Here Duke William asks Vital whether he has seen Harold’s army.

Fig. 22.

Fig. 23.

Fig. 24.

Fig. 25.

Fig. 26.

This man reports to Harold about Duke William’s army. Here Duke William exhorts his knights to prepare themselves manfully and wisely for battle against the English army ( figures 22, 23).

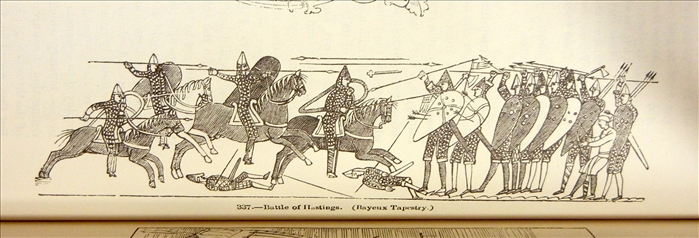

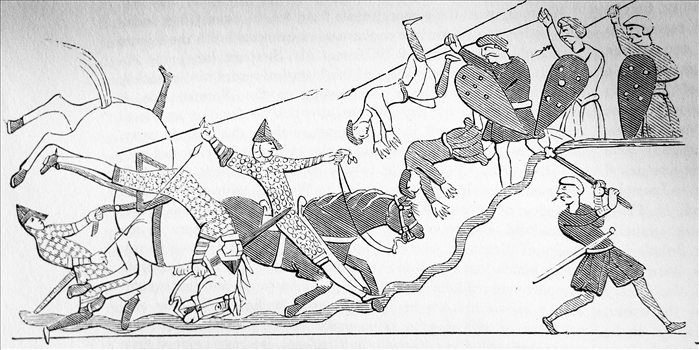

Here Leofwine and Gyrth, King Harold’s brothers, have been killed.

Here English and French together have been killed in battle ( figure 24).

Here Bishop Odo, holding a staff, encourages the young men. Here is Duke William [showing his face to the troops] ( figure 25). [Here is] Eustace. Here the French are fighting.

And those who were with Harold have been killed. Here King Harold has been killed ( figure 26). And the English have turned in flight.

Questions: Why would the tapestry’s designer(s) have included Harold’s adventures in Normandy? How is the Norman viewpoint evident? Compare this account with that in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (doc. 19). What does the tapestry reveal about warfare, everyday life, and material culture in the eleventh century?

21. Doing Penance for the Norman Victory

While pro-Norman historians presented the Norman Conquest as a just war sanctioned by the papacy, the eleventh-century Church felt a deep ambivalence about warfare between Christians. Issued by Norman bishops about four years following the Conquest, the following ordinances set forth the spiritual penalties to be paid by followers of Duke William of Normandy, now William I of England (r. 1066–87) for their role in the bloodbath at Hastings and the ravaging of the English countryside in the months afterward.

Source: ed. R. Allen Brown, The Norman Conquest of England: Sources and Documents (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1984; repr. 1995), pp. 156–57.

This is the institution of penance according to the decrees of the bishops of the Normans, confirmed by the authority of the supreme pontiff by his legate Ermenfrid, bishop of Sion, to be imposed upon those whom W[illiam] duke of the Normans by his command . . . [text missing] and who before this decree were his men and owed him military service as their duty.

1. Whoever knows that he has killed in the great battle is to do one year’s penance for each man slain.

2. Whoever struck another but does not know if that man was thereby slain, is to do forty days penance for each case, if he can remember the number, either continuously or at intervals.

3. Whoever does not know the number of those he struck or killed shall, at the discretion of his bishop, do penance for one day a week for the rest of his life, or, if he is able, make amends either by building a church or by giving perpetual alms to one.

4. Those who struck no one yet wished to do so are to do penance for three days.

5. Clerks who fought, or were armed for the purpose of fighting, because they are forbidden to fight are to do penance according to the institutions of canon law as if they had sinned in their own country. The penance of monks is to be determined according to their rule and the judgment of their abbot.

6. Those who fought motivated only by gain are to know that they owe the same penance as for homicide; but because they fought in a public war the bishops out of mercy have assigned them three years’ penance.

7. Archers who do not know how many they killed or wounded without killing are to do penance for three Lents.

8. That battle aside, whoever before the consecration of the king [William I] killed anyone offering resistance as he moved through the kingdom in search of supplies, is to do one year’s penance for each person so slain. Anyone, however, who killed not in search of supplies but in looting, is to do three years’ penance for each person so slain.

9. Whoever killed a man after the king’s consecration is to do penance as for wilful homicide, with this exception, that if the person killed or struck was in arms against the king the penance shall be as above.

10. Those who committed adulteries or rapes or fornications shall do penance as though they had sinned in their own countries.

11. Similarly concerning the violation of churches. Things taken from a church are to be restored to the church from which they were taken if possible. If this is not possible, they are to be given to some other church. If such restoration is refused, the bishops have decreed that no one is to sell or buy the property.

Questions: In what ways does this text add to our knowledge about the Norman Conquest? What do we learn about the Church’s attitude toward war and related acts of violence? Did the author(s) of this document regard the Conquest as a just war?

22. Castles in Norman England

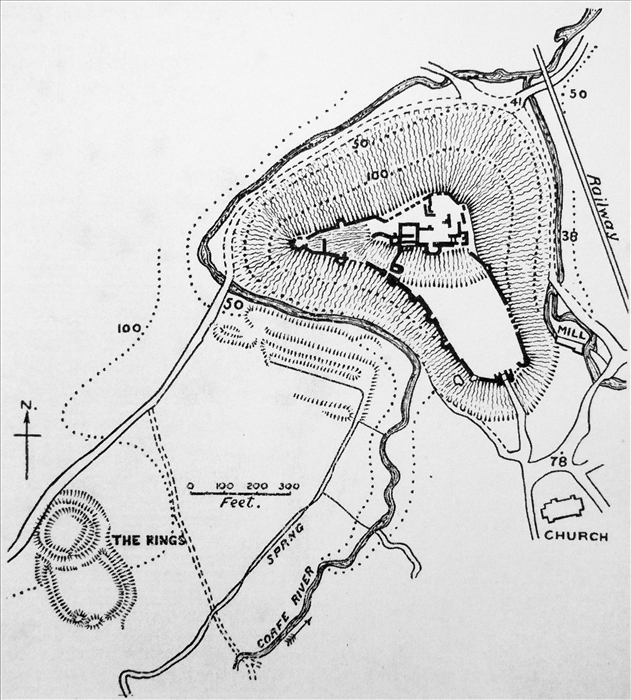

The Norman kings and their vassals transformed England’s landscape by building hundreds of castles. Most early castles featured a steep-sided motte, or earthen mound surmounted by a wooden or (less commonly) stone keep and protected by a wall, and a lower outer ward, or bailey, also protected by a defensive wall. In the decades after the Conquest, castles served as reminders of Norman might and deterrents to rebels. Many castle sites begun under William I and his sons continued to be defended and expanded for centuries, their wooden towers and palisades replaced by more permanent stone structures and periodically updated with new strategic features such as round towers, fortified gatehouses, and arrow-slits.

The plan below shows the defenses of Corfe Castle in Dorset, begun by William I on a natural hill that commanded the main route through the Purbeck Hills. The site’s strategic importance was such that the original castle (on the hilltop’s northeastern corner) was partially constructed of stone. Henry I had a massive stone keep added to the motte, and the site’s defenses were further expanded in the following centuries. In 1139, Corfe withstood a siege by King Stephen, who raised a siege castle, a motte-and-bailey structure (marked as “The Rings” on the plan), but abandoned the assault when his rival, the empress Matilda, landed in England. We lack a detailed account of this siege, but the story of King Stephen’s successful three-month siege of Exeter Castle in 1136, as told in the anonymous Deeds of Stephen, describes twelfth-century castle warfare and reminds us that the siege of Corfe could have turned out differently.

Sources: E. Armitage, The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles (London: J. Murray, 1912), fig. 13 (facing p. 128); Gesta Stephani, ed. and trans. K.R. Potter (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976), pp. 33, 39, 41, 43.

Fig. 27. Plan of Corfe Castle.

The Siege of Exeter, 1136

Exeter is a large town, with very ancient walls. . . . There is a castle in it raised on a very high mound surrounded by an impregnable wall and fortified with towers of hewn limestone. . . . In it, Baldwin de Redvers had placed a very strong force, no less than the flower of all England, chosen to resist the king. Bound by fealty and an oath never to yield to the king at all, they were shut up with his wife and children, ready for anything, and encircling the castle in close array with glittering arms they kept on hurling insults at the king and his men. Sometimes, too, sallying unexpectedly from secret posterns, they made violent charges with intent to inflict loss on the king’s army; frequently they shot arrows or flung javelins from the battlements and showed an aggressive spirit in many other ways as occasion required. However, the king, with a number of barons who had either come with him when he arrived or followed him speedily when they had gathered their forces, labored by many means to annoy them. For with a body of foot-soldiers, very completely equipped, he resolutely drove the enemy back and took an outwork raised on a very high mound to defend the castle, and he manfully broke the inner bridge, affording access from the castle to the city, and with wondrous art built great erections of timber as a hindrance to those trying to fight from the battlements. Also, day and night, he vigorously pressed on with the siege of the garrison; sometimes he joined battle with them by means of armed men crawling up the rampart; sometimes, by the aid of countless slingers, who had been hired from a distant region, he assailed them with an unendurable number of stones; at other times he summoned those who had skill in mining underground and ordered them to search into the bowels of the earth with a view to demolishing the wall; frequently, too, he devised engines of different sorts, some rising high in the air, others low on the ground, the former to spy out what was going on in the castle, the latter to shake or undermine the wall. The garrison on its side, offering a resolute and ready defense, cared nothing for all his engines, on which the cunning of the craftsmen had spent vast labor, so that with both parties putting vigor and resource into the struggle it was a great test of their shrewdness and quickness to act. . . .

In the meantime, while it was doubtful whether besiegers or defenders would prevail, and the king had stayed nearly three months there, with an expenditure on various items of as much as fifteen thousand marks, God, the disposer of all things, wishing to put an end to these great toils, so dried up the bountiful springs of the two wells in the castle, which had always bubbled with unfailing rills of water, that whereas formerly they had been fully enough for the daily needs of men and horses they were now hardly equal to allaying one man’s thirst. . . . So, burdened beyond what could be thought possible by undending watchfulness, brought to utter exhaustion by the different kinds of warfare they waged on the enemy from the wall, and finally parched and wasted by violent and unendurable thirst, they took counsel for their common interest. [The defenders agreed to surrender the castle, and chose representatives to seek favorable terms from the king.] At once two of them, the first in rank and dignity of the whole castle, were sent to the king, men already skilled to adorn their speech with charm and give their words, whenever it suited them, the turn that wisdom and eloquence most required. But he, under the persuasion of his brother the bishop of Winchester’s advice, showed them a front of iron. . . . Baldwin’s wife, too, unable to bear this harsh rejection of her companions, came to the king to offer entreaty on their behalf, barefooted, with her hair loose on her shoulders, and shedding floods of tears. He received her kindly, without haughtiness, both on account of the piety he felt for one of her sex in such wretched affliction and because of the high-born woman’s relations and friends who were toiling there with him in the siege, but after listening to her mournful and piteous supplications about the surrender of the castle he hardened his heart inexorably yet again and at last sent her back to her companions with nothing accomplished. [Eventually, Stephen’s advisors convinced him to accept the surrender of the garrison.] The king, encircled by a great number of barons, who not only besought him with entreaties but also influenced him by advice, at last gave way and granted their requests, and that he might win their closer attachment and have them more devoted to his service he allowed the besieged not only to go forth in freedom but also to take away their possessions and be the followers of any lord they willed. When they finally came forth you could have seen the body of each individual wasted and enfeebled with parching thirst, and once they were outside they hurried rather to drink a draught of any sort than to discharge any business whatsoever.

Questions: What are the strengths and weaknesses of Corfe Castle’s defenses? What challenges did attackers and defenders face in the siege of Exeter? How was the castle finally taken? Apart from its military function, what roles (political, social, economic, symbolic) might a castle have served?

23. Domesday Book

In 1086 William the Conqueror ordered a far-reaching census to be taken of the lands and resources in England (as described above in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for the year 1085, the anomaly in years being due to different ways of calculating the “new year” in the Middle Ages). The resulting returns were condensed and compiled into the large volume known to later generations as “Domesday Book,” because its testimony as to certain historical matters of status and tenure was the final authority and judgment. For historians, William’s census is an incomparable snapshot of almost the entire kingdom, providing a wealth of statistical detail that we have for no other part of Europe at this time.

Source: trans. E. Amt from Domesday Book 15: Gloucestershire, ed. J.S. Moore (Chichester: Phillimore, 1982), sections 162a G, 162d [1], 166c 28, 167a, 167b 34.

Gloucestershire

In the time of King Edward the city of Gloucester paid £36 (in counted coin), twelve sesters of honey (by the measure of that borough), 36 dickers of iron, 100 iron rods for nails for the king’s ships, and certain other minor customary payments in the king’s hall and chamber. Now the city itself pays the king £60 at the rate of 20d. per ora. And the king receives £20 from the mint.

In the demesne land of the king, Roger de Berkeley holds one house and one fishery in the town itself, and it is outside the king’s hand. Baldwin held this in the time of King Edward.

Bishop Osbern holds the land and dwellings which Edmar held; he pays 10s. with another customary payment.

Geoffrey de Mandeville holds six dwellings. In the time of King Edward these paid 6s. 8d. with another customary payment.

William Baderon holds two dwellings at 30d.

William the scribe holds one dwelling at 51d.

Roger de Lacy holds one dwelling at 26d.

Bishop Osbern holds one dwelling at 41d.

Berner holds one dwelling at 14d.

William Bald holds one dwelling at 12d.

Durand the sheriff holds two dwellings at 14d.

The same Durand holds one dwelling at 26d. and also one dwelling which renders no customary payment.

Hadwin holds one dwelling which pays rent but keeps back another customary payment.

Gosbert holds one dwelling; Dunning holds one dwelling; Widard holds one dwelling.

Arnulf the priest holds one dwelling which pays rent and keeps back another customary payment.

All these dwellings paid the royal customary payments in the time of King Edward. Now King William receives nothing from them, nor does Robert his official. These dwellings were in King Edward’s farm [his assets producing a fixed income] on the day he was alive and dead. But now they have been removed from the farm and from the king’s customary payments.

In the time of King Edward the king’s demesne in the city supplied all lodging and clothing. When Earl William took it into his farm it continued to supply clothing.

Sixteen houses used to be where the castle stands; now they are gone. And in the borough of the city fourteen houses have been destroyed. . . .

The King’s Land

King Edward held Cheltenham. There were eight and a half hides. One and a half hides belong to the Church; Reinbald holds them. In demesne were three plows, and twenty villeins and ten bordars [unfree peasants] and seven slaves with eighteen plows. The priests had two plows. There were two mills at 11s. 8d. King William’s reeve added to this manor two bordars and four villeins and three mills, of which two are the king’s and the third the reeve’s, and one additional plow there. In the time of King Edward it paid £9 5s., and 3,000 loaves of bread for dogs. Now it pays £20, twenty cows, 20 pigs, and 16s. for loaves of bread.

In King’s Barton King Edward had nine hides. Of these, seven were in demesne, where there are three plows, and fourteen villeins and ten bordars with nine plows. There are seven slaves. Two free men hold two hides from this manor and have there nine plows. They cannot separate themselves or their land from the manor. There was a mill at 4s. King William’s reeve added eight bordars and two mills and one plow. In the time of King Edward it paid £9 5s., and 3,000 loaves of bread for dogs. Now it pays £20, twenty cows, twenty pigs, and 16s. for loaves of bread.

Archbishop Ældred leased Brawn, a part of this manor. There were three virgates of land and three men there. Miles Crispin holds it now.

Alwin the sheriff leased another part, by the name of Upton. There was one hide of land and there are four men. Humfrey holds it now.

The same Alwin leased another part, by the name of Murrells. There are three virgates of land there. Nigel the physician holds it now. . . .

In Botloe Hundred

King Edward held Dymock. There were twenty hides and two plows in demesne there, and forty-two villeins and ten bordars and eleven freedmen having forty-one plows. There is a priest holding twelves acres there. There are four radknights [tenants owing escort duty] with four plows. There is woodland three leagues long and one league wide. The sheriff paid what he wished from this manor in the time of King Edward. King William held it in his demesne for four years. After that Earl William and his son Roger had it; on what terms, the men of the county do not know. Now it pays £21. . . .

Earl Hugh’s Land

In Bisley Hundred

Earl Hugh holds Bisley, and Robert holds it from him. There are eight hides there. In demesne there are four plows, and twenty villeins and twenty-eight bordars with twenty plows. There are six male slaves and four female slaves. There are two priests and eight radknights who have ten plows, and twenty-three other men who pay 44s. and two sesters of honey. There are five mills there at 16s. and woodland at 20s. And in Gloucester there are eleven burgesses who pay 66d. It was worth £24; now it is worth £20.

In Longtree Hundred

The same earl holds Westonbirt. Alnoth held it in the time of King Edward. There are three hides there which pay geld. In this hundred Leofwin held one hide.

In the same place the earl himself holds one hide at Througham. Leofnoth held it from King Edward and could go where he wished. This land pays geld. There are four bordars there with one plow and four acres of meadow. It is worth 20s.

In the same place the earl himself holds half a hide which Roger de Lacy claims at Edgeworth, as the county testifies. It is worth 10s. and pays geld.

In Witley Hundred

The earl himself holds Chipping Camden. Earl Harold held it. Fifteen hides pay geld there. In demesne are six plows, and fifty villeins and eight bordars with twenty-one plows. There are twelve slaves and two mills at 6s. 2d. There are three female slaves there. It was worth £30; now it is worth £20.

In Longtree Hundred

The earl himself holds two manors of four hides which pay geld, and two of his men hold them from him. Alnoth and Leofwin held them in the time of King Edward. There was no one who could answer for these lands, but they are valued by the men of the county at £8. . . .

Land of William Goizenboded

In Chelthorn Hundred

William Goizenboded holds Pebworth from the king. Wulfgeat and Wulfward held it in the time of King Edward as two manors. There are six hides and one virgate there. In demesne there is one plow, and one bordar and one slave. It was worth £7; now it is worth £4 10s.

The same William holds Ullington. One thegn held it in the time of King Edward. There are five hides there. In demesne are two plows, and two villeins and one Frenchman hold one and a half hides with one plow. Earl Algar made this manor part of Pebworth. It was worth 100s.; now it is worth 40s.

In Holmford Hundred

The same William holds Farmcote. Alwin held it. There are three hides which pay geld there. In demesne there are two plows, and four villeins with four plows, and thirteen male and female slaves. Geoffrey holds it from William. It was worth £10; now it is worth £3.

The same William holds Guiting Power. King Edward held it and leased it to Alwin his sheriff to have for his lifetime. But he did not give it as a gift, as the county testifies. When Alwin died, King William gave his wife and lands to a young man named Richard. Now Richard’s successor William holds this land thus. There are ten hides, of which nine pay geld. In demesne there are four plows, and four villeins and three Frenchmen and two radknights and a priest, with two bordars; all the men have five plows between them. There are eleven male and female slaves and two mills at 14s. Five salt-houses there pay twenty loads of salt. In Winchcombe two burgesses pay 11s. 4d. It was worth £16; now it is worth £6.

Questions: How is Domesday Book organized? How are people classified? What differences between towns and the countryside are evident? Which properties are most valuable? What kinds of revenue do the king and lords receive? What changes have occurred since the time of King Edward?

24. Orderic Vitalis’s Account of his Life

Orderic Vitalis (1075–ca 1142), one of the great historians of the Anglo-Norman world, ended his lengthy history with the following brief account of his own life. It is included here as an example of the experience of a child born after the Conquest, to an English mother and Norman father, and of a common type of monastic career, that of a child oblate, in the last quarter of the eleventh century.

Source: trans. M. Chibnall, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, 6 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969–80), vol. 6, pp. 551, 553, 555, 557.

Now indeed, worn out with age and infirmity, I long to bring this book to an end, and it is plain that many good reasons urge me to do so. For I am now in the sixty-seventh year of my life and service to my lord Jesus Christ, and while I see the princes of this world overwhelmed by misfortunes and disastrous setbacks I myself, strengthened by the grace of God, enjoy the security of obedience and poverty. . . . I give thanks to you, supreme king, who freely created me and ordained my life according to your gracious will. For you are my king and my God, and I am your servant and the son of your handmaid, one who from the beginning of my life has served you as far as I was able. I was baptized on Holy Saturday at Atcham, a village in England on the great river Severn. There you caused me to be reborn of water and the Holy Spirit by the hand of Orderic the priest, and imparted to me the name of that priest, my godfather. Afterward when I was five years old, I was put to school in the town of Shrewsbury, and performed my first clerical duties for you in the church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul the apostles. There Siward, an illustrious priest, taught me my letters for five years, and instructed me in psalms and hymns and other necessary knowledge. Meanwhile you honored this church on the River Meole, which belonged to my father, and built a holy monastery there through the piety of Earl Roger. It was not your will that I should serve you longer in that place, for fear that I might be distracted among kinsfolk, who are often a burden and a hindrance to your servants, or might in some way be diverted from obeying your law through human affection for my family. And so, O glorious God, who commanded Abraham to depart from his country and from his kindred and from his father’s house, you inspired my father Odelerius to renounce me utterly, and submit me in all things to your governance. So, weeping, he gave me, a weeping child, into the care of the monk Reginald, and sent me away into exile for love of you and never saw me again. And I, a mere boy, did not presume to oppose my father’s wishes, but obeyed him willingly in all things, for he promised me in your name that if I became a monk I should taste the joys of Paradise with the Innocents after my death. So with this pact freely made between me and you, for whom my father spoke, I abandoned my country and kinsfolk, my friends and all with whom I was acquainted, and they, wishing me well, with tears commended me in their kind prayers to you, O almighty God, Adonai. Receive, I beg thee, the prayers of these people and, O compassionate God of Sabaoth, mercifully grant what they asked for me.

And so, a boy of ten, I crossed the English Channel and came into Normandy as an exile, unknown to all, knowing no one. Like Joseph in Egypt, I heard a language which I did not understand. But you suffered me through your grace to find nothing but kindness and friendship among strangers. I was received as an oblate monk in the abbey of Saint-Évroul by the venerable Abbot Mainer in the eleventh year of my age, and was tonsured as a clerk on Sunday, 21 September. In place of my English name, which sounded harsh to the Normans, the name Vitalis was given me, after one of the companions of Saint Maurice the martyr, whose feast was being celebrated at that time. I have lived as a monk in that abbey by your favor for fifty-six years, and have been loved and honored by all my fellow monks and companions far more than I deserved. I have labored among your servants in the vineyard of the choice vine, bearing heat and cold and the burden of the day, and I have waited knowing that I shall receive the penny that you have promised, for you keep faith. I have revered six abbots as my fathers and masters because they were your vicars: Mainer and Serlo, Roger and Warin, Richard and Ralph. . . . On 15 March, when I was sixteen years old, at the command of Serlo, abbot elect, Gilbert, bishop of Lisieux, ordained me subdeacon. Then two years later, on 26 March, Serlo, bishop of Séez, laid the stole of the diaconate on my shoulders, and I gladly served you as a deacon for fifteen years. At length in my thirty-third year William, archbishop of Rouen, laid the burden of priesthood on me on 21 December. On the same day he also blessed two hundred and twenty priests, with whom I reverently approached your holy altar, filled with the Holy Spirit; and I have now loyally performed the sacred offices for you with a joyful heart for thirty-four years. . . .

Questions: How does Orderic’s account of his life reflect the times he lived in and his profession? What is his attitude toward his childhood? What does the text suggest about the rationale of child oblation to monastic houses?

25. Anselm of Canterbury on His Feud with William Rufus

In 1070 William I appointed his spiritual advisor, Lanfranc, archbishop of Canterbury and tasked him with the administrative and physical reconstruction of the Anglo-Saxon Church. At Lanfranc’s death in 1089, William I’s son, William II, left the see of Canterbury vacant for years while he pocketed its income. In 1093, believing himself near death, William II consented to the election of Lanfranc’s protégé, the ardent reformer Anselm, as archbishop of Canterbury. William recovered, but he and Anselm soon clashed: they backed different candidates in the ongoing papal schism and disagreed about how much control kings should exercise over the Church. Anselm fled England in 1097 and spent three years on the continent. In this letter the exiled Anselm recounts his falling-out with the king and pleads his case to the newly elected pope Paschal II.

Source: trans. W. Fröhlich, The Letters of Saint Anselm of Canterbury (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1993), vol. 2, pp. 156–59.

Anselm to Pope Paschal II (late 1099 or early 1100)

To his reverend lord and father Paschal, supreme pontiff: Anselm, servant of the church of Canterbury, sending due subjection from the bottom of his heart and the devotion of his prayers, for what they are worth.

The reason why I delayed so long sending a message to your highness after we thanked God and rejoiced at the certain news of your elevation [to the papal throne], was that a messenger from the king of the English came to the venerable archbishop of Lyon to discuss our case, yet without offering anything which could be accepted. Having heard the archbishop’s reply he went back to the king, promising to return to Lyon very soon. I awaited him there in order to learn something I could tell you about the king’s intention but he did not come. Therefore I shall state my case to you briefly because, when I was staying in Rome I often spoke about it to the lord Pope Urban [II, Paschal’s predecessor] and to many others, as I expect your holiness knows.

In England I saw many evils which it was my duty to correct, but I could neither correct them nor tolerate them without committing a sin. The king demanded of me that in the name of righteousness I should give my consent to his intentions which were against the law and the will of God. For he was unwilling that the pope should be acknowledged or appealed to in England without his command, or that I should send the pope a letter, or receive one sent by him, or obey his decrees. He has not permitted a council to be held in his kingdom since he became king thirteen years ago. He gave church lands to his own men. When I sought advice on all these and other similar matters, everybody in his kingdom, even my own suffragan bishops, refused to give me any counsel except that which agreed with the king’s will. Seeing these and many other things contrary to the will and law of God, I begged the king’s leave to go to the apostolic see so that there I might receive counsel for my soul and for the office laid upon me. The king replied that I had offended him solely by asking for this leave and demanded that either I should give him satisfaction for doing so, as if for an offense, and an assurance that I would never again ask for this leave or at any time appeal to the pope, or else I should leave his realm forthwith. I chose to leave rather than to consent to such an abominable thing. I came to Rome, as you know, and set the whole matter before the lord pope. No sooner had I left England than the king openly laid a tax on the food and clothing of our monks, invaded the entire archbishopric [of Canterbury] and turned it to his own use. He was admonished and entreated by the lord pope [Urban II] to put this right, but he scorned this and still persists. It is now already the third year since I left England. I have spent the little which I took with me as well as much which I borrowed and which I still owe. Thus, owing more than I have, being detained at the house of our venerable father, the archbishop of Lyon, I am supported by his kind generosity and generous kindness.

I do not say this as if longing to return to England but fearing that your highness may be angry with me if I do not notify you about my situation. Therefore I pray and beseech you, with as much fervor as I can, not to command me to return to England under any circumstances, unless in such a way that I be allowed to place the law and will of God and the apostolic decrees above the will of man, and unless the king restores to me the church lands and whatever he took from the archbishopric because I appealed to the apostolic see, or indeed offers fair compensation to the Church for all those things. Otherwise I would make it appear that I put man before God and that I was justly despoiled for wanting to have recourse to the apostolic see. It is quite obvious what an injurious and detestable example this would be for my successors.

Some ill-informed people inquire as why I do not excommunicate the king; but those who are wiser and have well-advised opinions counsel me not to do that, for it is not up to me both to lodge the complaint and to pronounce the punishment. Moreover, I have been told by my friends who are under that king that my excommunication, if pronounced, would be scorned by him and turned into ridicule. The prudence of your authority needs no advice from us on this matter.

We pray that almighty God may make all your actions pleasing to him and make his Church long rejoice about your rule and your prosperity. Amen.

Questions: What accusations does Anselm make against William II? How did William and Anselm each define the relationship between royal authority and the Church in England? How did each attempt to gain the upper hand in their dispute? What does the document suggest about why kings might have opposed some aspects of Church reform?

26. Gilbert Crispin’s Disputation of a Jew with a Christian

Gilbert Crispin, a Norman monk and scholar, was appointed abbot of Westminster Abbey in 1085. The Disputation was written in the 1090s and inspired by discussions with Gilbert’s friend Anselm of Canterbury, as well as by contact with members of London’s Jewish community. Gilbert’s Jewish interlocutor would have belonged to the first generation of Jews brought by King William I from Normandy. By 1100 Jewish communities were established in several English towns, their members defined as the king’s property, and they were accordingly granted various privileges, including the right to travel without paying tolls and to swear oaths on the Torah rather than the Christian scriptures. The excerpts below give a good sense of the issues commonly raised in theological debates between Christians and Jews.

Source: ed. Joseph Jacobs, The Jews of Angevin England: Documents and Records (London: David Nutt, 1893), pp. 7–12; revised, with additional material trans. K.A. Smith from The Works of Gilbert Crispin, Abbot of Westminster, ed. Anna Sapir Abulafia and G.R. Evans, Auctores Britannici Medii Aevi 8 (London: Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1986), pp. 8–12, 15, 17–18, 27–29, 39–40, 50–51.

To the reverend father and lord Anselm, archbishop of the holy church of Canterbury, his servant and son, Brother Gilbert, proctor and servant of Westminster Abbey, wishes him happy longevity in this life and blissful eternity in the future one.

I send you a little work to be submitted to your fatherly prudence. I wrote it recently, putting to paper what a Jew said when formerly disputing with me against our faith in defense of his own law, and what I replied in favor of our faith against his objections. I do not know where he was born, but he was educated at Mainz; he was well versed even in our law and literature, and had a mind practiced in the scriptures and in disputes against us. He often used to come to me as a friend both for business and for the pleasure of seeing me, since in certain things I was very necessary to him, and as often as we came together we would soon begin talking in a friendly spirit about the scriptures and our faith. Now on a certain day, God granted both of us more leisure than usual, and soon we began questioning one another as we were accustomed to do. And as his objections were consistent and well-ordered, and as he explained his former objections equally well, and our reply responded to his objections point for point, and by his own admission seemed equally well supported by the testimony of the scriptures, some of the bystanders asked me to preserve our disputation, so that perhaps it might be of use to others in future. . . .

Here begins the disputation of a Jew with a Christian, as set forth by Abbot Gilbert of Westminster.

The Jew: Because Christians are accustomed to speak to you in learned letters and with eloquent speech, I ask you to bear with me in a spirit of tolerance. With what reason or by what authority do you blame us Jews because we observe the law given by God to the lawgiver Moses? For if it is a good law and given by God it should be observed. For whose command is to be observed if the orders of God are not to be obeyed? But if the law should be observed, why do you treat those who observe it like dogs, driving them away with sticks and pursuing them everywhere? . . .

The Christian: First, let us speak of the law which, we argue, is good and given by God. And therefore, everything written in scripture is to be understood in a divine sense and heeded in its season, and we confirm that it is to be observed. Indeed, we hold that the commands of the law are to be understood in a divine sense because, if men understood them in every sense and followed them to the letter, much confusion and contradiction would result. For example, when the creation of the world was complete, as Moses writes: “God saw all the things that he had made, and they were very good” (Genesis 1:31). How, then, can he later write of the separation of the animals into clean and unclean, into those which may be used and those which he orders may not even be touched under penalty of death (Leviticus 5:2, 11:24)? For how can that which is “unclean” be called “very good?” . . .

The Jew: If the word of God is to be observed at one time or another, so that it is annulled at one time and to be observed at another, and thus in the vicissitude of time the divine sanctions are changed, how stands it with the verse, “And God has spoken once” (Psalm 61:12)? Why was it said, “Forever O Lord, your word will stand firm in heaven” (Psalm 118:89)? What difference does it make, I ask, why God judged this animal to be clean and that animal to be unclean, or permitted this one to be used and forbade that one to be used? For “Who has directed the Lord’s spirit, or been his counselor” (Isaiah 40:3)? that he should permit this or forbid that? . . .

The Christian: It is true that God spoke once, and it is impossible that any word of God can be annulled: the divine sanctions are not changed by any vicissitudes of time, for Christ came not to deliver the law, but to fulfill it. As he says, “I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is fulfilled” (Matthew 5:17–18). How could Christ ever wish to condemn the law, as he threatens that “not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is fulfilled?” For he does not wish to dissolve the law but to fulfill it. The law prohibits homicide, Christ prohibits anger and hatred; the law forbids actual adultery, Christ himself even forbids carnal desire. The law forbids you to use pork, and at that time abstinence from that animal was necessary for you, since it was a symbol of future truth, and a symbol is to be preserved till the truth itself comes. But now it is necessary neither for you nor for us since the truth of the symbol is present. . . .

The Jew: What reason, what scriptural authority is there, that I should believe that God can become a man, or come forth as a man already created? If there is no transmutation in God nor any shadow of change, how could it be believed that so great a change could occur in him that God could become man, the creator a creature, and the incorruptible corrupted? How, I ask, could we accept that “In the beginning, O Lord, you founded the earth, and the heavens are the works of your hands. They shall perish but you remain, and all of them shall grow old like a garment . . . But you are always the same, and your years shall never decline” (Psalm 101:26–28). How could God be always the same if he became a man? If he is infinite how could he be circumscribed in the mean and small dimensions of human limbs? . . .

The Christian: We do not fear any opposition to this revelation, nor are we afraid of finding any disagreement in the scriptures. But meanwhile let us unloose the scriptural authorities, upon which, with God’s help, we will build a proof that God was made man and was seen by men. For openly and without any ambiguity Jeremiah the prophet speaks thus: “This is our God, and none will be likened to him. He has found the whole way of knowledge, and gave it to Jacob his son and Israel his elect: after this he was seen on earth and conversed with men” (Baruch 3:36–38). “After this,” meaning after the law was given, after ‘the way of knowledge was given to Jacob his son and Israel his elect, God was made man “and conversed with men,” born from a virgin, from the closed womb of his mother, with his divinity preserved intact. . . .

The Jew: From that very quotation of yours it can be established that the Christians should be confounded, for they “adore images and rejoice in their idols” (cf. Psalm 96:7). For you portray God himself as a wretch hanging on the beam of the cross transfixed with nails—a horrible sight, and yet you adore it. . . . Other times you depict God sitting on a lofty throne and making signs with an outstretched hand, and around him, as if for greater dignity, an eagle and a man, a calf, and a lion. Christians sculpt and paint images, and they adore them and tend them, though the God-given law forbids this in every way. For it is written in Exodus (20:4–5): “You shall not make for yourself a graven image, nor the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, nor of those things that are in the waters. You shall not adore them, nor serve them.” Therefore the law condemns any graven image and judges it abhorrent.

The Christian: If the law condemns all sculpture and nothing is to be imitated in an effigy, Moses sinned, who figured and painted the likenesses of things; indeed, the Lord himself sinned, who commanded them to be figured and painted. . . . And so, when the Christian adores the cross, with the worship due to the divine religion, he adores the passion of Christ on the cross, who on account of mankind endured the passion in the person of God. . . . The Christian worships no image with divine worship, but he cherishes with honor the representation of sacred things, and honors figures and pictures.

Questions: What does the text tell us about Jewish-Christian interactions in Norman England? What theological issues divided Jews and Christians? How does each debater use reason and scriptural evidence to support his positions? How would you describe the debate’s overall tone?

27. Church Reform: The Council of Westminster

In a process that paralleled the disenfranchisement of the Anglo-Saxon nobility, William I and his successors replaced the majority of Anglo-Saxon bishops and abbots with foreigners. Under the reforming archbishops of Canterbury Lanfranc (r. 1070–89) and Anselm (r. 1093–1109), the English Church was brought into the orbit of the reforming papacy, and new legislation was passed which outlawed simony (the buying and selling of church offices) and clerical marriage and generally required the clergy to live in a manner that distinguished them from, and underscored their spiritual superiority over, the laity. The first general council convened in England by Anselm, the Council of Westminster, echoes the agenda of the Gregorian Reform but expresses concerns particular to the English context.

Source: trans. H. Gee and W.J. Hardy, Documents Illustrative of English Church History (London: Macmillan, 1914), pp. 61–63; revised.

1. The cunning heresy of simony was condemned by the said council. The following were found guilty of this crime and deposed: Guy, abbot of Pershore, Wimund of Tavistock, and Ealdwine of Ramsey. Some others, who had not yet been consecrated, were removed from their abbacies, namely Godric of Peterborough, Hamo of Cerne, and Æthelric of Milton. . . .

2. Bishops are not to undertake the office [of judge] in secular cases, and are not to dress as laymen . . . , and are always and everywhere to have honest persons who may serve as witnesses to their conduct. . . .

5. That no archdeacon, priest, deacon, or canon is to marry or retain a wife, and that any subdeacon who is not a canon, having married after making a vow of chastity, be bound by the same rule.

6. That as long as a priest has illicit intercourse with a woman he is not a lawful priest, and so is not permitted to celebrate mass, and if he does so his mass is not to be attended.

7. That no one is to be ordained to the subdiaconate or a higher office without professing chastity.

8. That the sons of priests are not to inherit their fathers’ churches.

9. That no clerks are to be the agents or proctors of secular men, nor serve as judges in capital cases.

10. That priests are not to go on drinking bouts. . . .

12. That monks or clerks who have forsaken their order must either return or be excommunicated.

13. That clerks must have visible tonsures.

15. That churches and prebends [income from churches] are not to be bought.

16. That no new chapels are to be founded without the bishop’s consent. . . .

18. That abbots do not make knights, and that they eat and sleep in the same house with their monks except when they are prevented from doing so by necessity.

19. That monks impose no penance on any without permission of their abbot, and that abbots can give such permission only to those over whom they have spiritual charge.

20. That monks not be godfathers, nor nuns godmothers. . . .

22. That monks accept no churches except through bishops, and that when these are given to them monks must not so deprive them of their rents that the priests serving there lack what is needed for themselves and the churches.

23. That marriage vows made in secret and without witnesses are to be considered void when denied by either party.

24. That men should wear their hair short enough that part of their ears be visible and their eyes not covered.

25. That relations up to the seventh degree be not married, nor, if they are already married, should they continue to live together; and if anyone be aware of this incest and not declare it, let him know that he is a party to the same guilt.