Chapter Three

The Angevin Era, 1154–1216

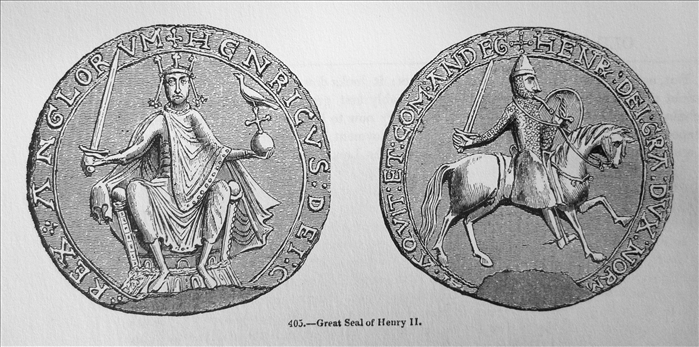

Fig. 29. Seal of Henry II. A nineteenth-century engraving of the great seal of King Henry II (r. 1154–89). Seals were used by medieval kings, and increasingly by other individuals, to authenticate documents, much as signatures are used today. In a pattern typical of the Norman and Angevin kings, Henry is shown enthroned as king of England on the front and mounted as duke of Normandy on the reverse.

33. Gerald of Wales’s Description of Henry II

One of the dominant figures in twelfth-century Europe, Henry II (r. 1154–89), the son of the empress Matilda, left multiple legacies to England: in law and justice, in finance and administration, in relations between the king and his vassals, and between the royal government and the Church. Here the Welsh-Norman historian Gerald of Wales, who served as Henry’s chaplain for years and thus knew him well, describes the king.

Source: trans. E.P. Cheyney, Readings in English History Drawn from the Original Sources (Boston: Ginn and Company, 1922), pp. 137–39, with additional material trans. E. Amt from Giraldi Cambrensis Opera, ed. J.F. Dimock (London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1867), pp. 303–6.

Henry II, king of the English, was a man of ruddy complexion, with a large, round head, piercing, blue-gray eyes, fierce and glowing red in anger, a fiery face and a harsh voice. He was short of neck, square of chest, strong of arm, and fleshy in body. By nature rather than from over-indulgence he had a large paunch, yet not such as to make him sluggish. For he was temperate in food and drink, sober and inclined to be prudent in all things so far as this is permitted to a leader. And so that he might overcome this unkindness on the part of nature by diligence, and lighten the fault of the flesh by greatness of spirit, often by an internal warfare, as it were conspiring against himself, he exercised his body with unbounded activity. Besides, wars frequently occurred; in these he was preeminent in action and gave himself not a moment of rest. In times of peace as well, he took no rest or quiet for himself. Immoderately devoted to hunting, he went out at dawn on a swift horse. Now descending into the valleys, now penetrating the forests, now ascending the peaks of mountains, he spent his days in activity; when he returned to his home in the evening, either before or after the meal one rarely saw him seated. Then after such strenuous exertion on his part he used to weary the whole court by continual marches. But since this is most useful in life: “nothing to excess,” and no remedy is purely good, so he accelerated other problems in his body with frequent swelling of his hands and feet, increased by abuse to these limbs sustained in riding; and if nothing else, he certainly hastened old age, the mother of all ills.

He was a man of medium height, a thing which could not be said of any of his sons—the two elder a little exceeding medium height, while the two younger remained below that stature. Setting aside the activities of his mind and his impulse to anger, he was chief among the eloquent, and—a thing which is most conspicuous in these times—he was most skilled in letters; a man easy to approach, tractable, and courteous; in politeness second to none. As a leader he had so strong a sense of duty that, as often as he conquered in arms, he himself was more often conquered by his sense of justice. Strenuous in war, in peace he was cautious. Often in martial affairs he shrank from the possible disasters of war, and wisely tried all else before resorting to arms. He wept over those lost in the line of battle more than their leader; he was more gentle to the dead soldier than to the living, mourning with much greater grief over the dead than winning the living with his love. When disasters threatened, none was kinder; when security was gained, no one was more severe. Fierce toward the unconquered, merciful toward the conquered; strict toward those at home, easy toward strangers; in public lavish, in private prudent. If he had once hated a man, rarely afterward would he be fond of him, and scarcely ever would he hate one whom he had once loved. He was especially fond of hawking; he was equally delighted with dogs, which followed wild beasts by sagacity of scent, taking pleasure as well in their loud sonorous barkings as in their swift speed. Would that he had been as much inclined to devotion as he was to hunting!

Fig. 30. Effigies of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. King Henry II (r. 1154–89) and Queen Eleanor are shown here in nineteenth-century engravings drawn from their tomb effigies at the Abbey of Fontévrault in Anjou. From the time of William the Conqueror until the early thirteenth century, most English kings were buried in religious establishments in their French, rather than their English, territories.

After the grave enmity with his sons, instigated, it is said, by their mother, he was a public violator of his marriage vows. With a natural inconstancy, he often and freely broke his word. For whenever matters became difficult, he preferred to break his promise rather than turn from what he was doing, and he would sooner hold his words invalid than abandon his deeds. In all his actions he was prudent and moderate; and on account of this, the remedy going somewhat too far, he was dilatory in doing right and justice, and, to the great harm of his people, he was slow to respond in such matters. And justice should be freely granted, according to God, but justice which is priceless came at a price, and everything available was for sale at a high price and for a profit. . . .

He was a most diligent maker and keeper of peace; he was incomparable in giving alms, especially for the support of the land of Palestine. He was a lover of humility, an enemy of fame and pride. “He filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he sent empty away. He exalted the meek and cast down the mighty from their seats (Luke 1:53).”

He detestably presumed to usurp things which are God’s; zealous for justice, though not from knowledge, he joined the rights of the kingdom to those of the Church, gathering both to himself. Although he was a son of the Church and had drawn from her the honor of his position, either unmindful or inattentive to the holy power which had been conferred upon him, he devoted scarcely any time to divine services; and even this little time, perhaps on account of great affairs of state and for the sake of the public welfare, he consumed more in plans and talk than in true devotion. The revenues of the vacant sees he diverted into the public treasury. The mass became corrupted by the working of the leaven, and while the royal purse kept receiving that which Christ demands as his own, new troubles kept arising. In the meantime he kept pouring out the universal treasure, giving to a wicked soldiery what ought to have been given to the priesthood.

Very wisely he planned many things, arranging them carefully. These affairs did not always result in success—in fact, they often turned out quite the opposite. But never did any great disaster occur which did not spring from causes connected with his family. As a father he enjoyed the childhood of his children with natural affection; through their elder years, however, he treated them more as a stepfather. And although great and famous sons were his, nevertheless they were a hindrance to his perfect happiness. Perhaps this was according to his deserts, since he always pursued his successors with hatred. . . . Whether because of some fault in marriage, or as punishment for some parental misdeed, there was never peace between the father and his sons or among the sons themselves. But having summarily subdued the foes of the kingdom and the disturbers of peace, brothers and sons, natives and foreigners, he saw all that followed went according to his will. If only he had also, by the proper service of good works, finally recognized this ultimate divine favor.

Questions: Which elements of this portrait seem to be standard traits associated with any king? Which have the ring of reality? What does Gerald admire in the king, and what does he criticize? Why? What aspects of Henry’s character would most appeal to the twelfth-century public?

34. The Constitutions of Clarendon

Since one of Henry II’s projects was the standardization of legal procedures, he wished to assert more authority over the Church, whose ecclesiastical courts were felt to offer excessive protection to clergy who broke the law. In 1164 Henry sought the agreement of church leaders to the Constitutions of Clarendon, which had been drafted by royal officials and which Henry, somewhat disingenuously, claimed were merely a restatement of well-established customs governing relations between the English Church and government. But Thomas Becket, Henry’s former chancellor and now archbishop of Canterbury, balked at approving the Constitutions, and thus began his famous quarrel with the king.

Source: trans. H. Gee and W.G. Hardy, Documents Illustrative of the History of the English Church (London: Macmillan, 1910), pp. 68–72; revised.

In the year 1164 from our Lord’s incarnation, the fourth of the pontificate of Alexander [III], the tenth of Henry II, most illustrious king of the English, in the presence of the same king, was made this remembrance or acknowledgment of a certain part of the customs, liberties, and dignities of his ancestors, that is, of King Henry [I] his grandfather, and of others, which ought to be observed and held in the realm. And owing to strifes and dissensions which had taken place between the clergy and justices of the lord king and the barons of the realm, in respect of customs and dignities of the realm, this recognition was made before the archbishops and bishops and clergy, and the earls and barons and nobles of the realm. And these same customs were recognized by the archbishops and bishops, and earls and barons, and by those of high rank and age in the realm, namely, Thomas, archbishop of Canterbury, and [12 other bishops] conceded, and by word of mouth steadfastly promised on the word of truth, to the lord king and his heirs, should be kept and observed in good faith and without evil intent, these being present: [38 barons and royal servants, listed by name], and many other magnates and nobles of the realm, clerical as well as lay.

Now of the acknowledged customs and dignities of the realm a certain part is contained in the present document, of which part these are the chapters:

1. If controversy shall arise between laymen, or clergy and laymen, or clergy, regarding advowson [the right to appoint clergy to particular positions] and presentation to churches, let it be treated or concluded in the court of the lord king.

2. Churches belonging to the fee of the lord king [churches on the royal demesne] cannot be granted in perpetuity without his own assent and grant.

3. Clerks cited and accused of any matter shall, when summoned by the king’s justice, come into his own court to answer there concerning what it shall seem to the king’s court should be answered there, and in the church court for what it shall seem should be answered there; yet so that the king’s justice shall send into the court of holy Church to see in what way the matter is there treated. And if the clerk be convicted, or shall confess, the Church must no longer protect him.

4. Archbishops, bishops, and parish clergy of the realm are not allowed to leave the kingdom without license of the lord king; and if they do leave, they shall, if the king so please, give security that neither in going nor in staying nor in returning, will they seek to harm the lord king or realm.

5. Excommunicate persons are not to give pledge for the future, nor to take oath, but only to give security and pledge of abiding by the Church’s judgment that they may be absolved.

6. Laymen are not to be accused except by proper and legal accusers and witnesses in the presence of the bishop, so that the archdeacon does not lose his right nor anything due to him thence. And if the accused be such that no one wills or dares to accuse them, the sheriff, when requested by the bishop, shall cause twelve lawful men from the neighborhood or the town to swear before the bishop that they will show the truth in the matter according to their conscience.

7. No one who holds of the king as a tenant in chief, and none of his demesne officers are to be excommunicated, nor are the lands of any one of them to be put under an interdict unless first the lord king, if he be in the country, or his justice if he be outside the kingdom, be applied to in order that he may do right for him; and so that what shall appertain to the royal court be concluded there, and that what shall belong to the church court be sent to the same to be treated there.

8. If appeals shall occur, they must proceed from the archdeacon to the bishop, and from the bishop to the archbishop. And if the archbishop fails to deliver justice, they must come at last to the lord king, that by his command the dispute be concluded in the archbishop’s court, so that it must not go further without the assent of the lord king.

9. If a dispute shall arise between a clerk and a layman, or between a layman and a clerk, as to whether a given tenement is held in free alms or as a lay fee, it shall be concluded by the consideration of the king’s chief justice on the award of twelve lawful men . . . before the king’s justiciar himself. And if the judgment be that it is held in free alms, it shall be pleaded in the church court, but if [the judgment be that it is held as a] lay fee, unless both claim under the same bishop or baron, it shall be pleaded in his own court, so that for making the award he who was first seised [in possession] will not lose his seisin until the matter is settled by the plea.

10. If anyone living in a city, or castle, or borough, or a demesne manor of the lord king, is cited by archdeacon or bishop for any offense for which he ought to answer, and he refuses to give satisfaction at their citations, it is lawful to place him under interdict; but he must not be excommunicated before the chief officer of the lord king of that town be applied to, in order that he may adjudge him to come for satisfaction. And if the king’s officer fails to do this, he shall be at the king’s mercy, and thereafter the bishop shall be able to restrain the accused by ecclesiastical justice.

11. Archbishops, bishops, and all persons of the realm who hold of the king as tenants in chief, have their possessions from the lord king as a barony, and are therefore answerable to the king’s justices and ministers, and must follow and do all royal rights and customs, and like all other barons, must be present at the trials of the court of the lord king with the barons until it comes to a judgment of loss of limb, or death.

12. When an archbishopric or bishopric is vacant, or any abbey or priory of the king’s demesne, it must be in his own hand, and from it he shall receive all revenues and rents as demesne. And when it is time to install a clergyman in that church, the lord king must cite the chief clergy of the church, and the election must take place in the chapel of the lord king himself, with the assent of the lord king, and the advice of the persons of the realm whom he has summoned to do this. And the person elected shall there do homage and fealty to the lord king as to his liege lord for his life and limbs and earthly honor, saving his order, before he is consecrated.

13. If any of the nobles of the realm forcibly prevent the archbishop or bishop or archdeacon from doing justice in regard of himself or his people, the lord king must bring them to justice. And if by chance anyone should deprive the lord king of his rights, the archbishops and bishops and archdeacons must judge him, so that he gives satisfaction to the lord king.

14. No church or cemetery is to detain the goods of those who are under forfeit of the king against the king’s justice, because they belong to the king himself, whether they be found inside churches or outside.

15. Pleas of debts due under pledge of faith or without pledge of faith are to be in the king’s justice.

16. Sons of villeins ought not to be ordained without the assent of the lord on whose land they are known to have been born.

Now the record of the aforesaid royal customs and dignities was made by the said archbishops and bishops, and earls and barons, and the nobles and elders of the realm, at Clarendon, on the fourth day before the Purification of the Blessed Mary [29 January], ever Virgin, the lord Henry the king’s son with his father the lord king being present there. There are, moreover, many other great customs and dignities of holy mother Church and the lord king and the barons of the realm which are not contained in this writing. And let them be safe for holy Church and the lord king and his heirs and the barons of the realm, and be inviolably observed.

Questions: What are the potential areas of disagreement? What are the implications of the king’s assertions of authority over the English Church? What precedents have you encountered, in earlier documents, for the king’s position? What are the implications of Becket’s resistance to the Constitutions?

35. The Murder and Miracles of Thomas Becket

The quarrel between Henry II and Archbishop Thomas Becket, in which the Constitutions of Clarendon (doc. 34) featured prominently, quickly escalated and resulted in Becket’s exile overseas. Years of bitter argument and tense negotiation followed. In 1170 a compromise allowed the archbishop to return home, which he did in December, the point at which the excerpt below takes up the story. The clerk Edward Grim, author of the biographical extract below, was an eyewitness of and participant in the events at Canterbury, though not those at the royal court in France. The miracles that follow were selected from over four hundred such stories collected by William of Canterbury within five years of Becket’s death.

Source: Grim, trans. W.H. Hutton, S. Thomas of Canterbury, An Account of His Life and Fame from the Contemporary Biographers and Other Chroniclers (London: David Nutt, 1899), pp. 233–45, revised; additional material trans. E. Amt from Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, ed. J.C. Robertson (London: Rolls Series, 1875–83), vol. 1, pp. 145, 147, 154, 207, 213–14, 326, 362, 393; vol. 2, pp. 428–30; miracles, trans. E.P. Cheyney, Readings in English History Drawn from the Original Sources (Boston: Ginn and Company, 1922), pp. 160–64; revised.

Edward Grim’s Life of Thomas Becket

Having returned [to England], therefore, with the highest purity and devotion of spirit, the archbishop celebrated the holy nativity of the Savior, cheerfully reminding his people that his own way did not lie among men. On the day of the Lord’s nativity, as soon as he had finished his sermon to the people, with a terrible sentence he condemned [Robert de Broc,] one of the king’s men, who, had attacked some of the archbishop’s servants the day before and, to insult them, had shamefully cut off their horses’ tails. And he laid a similar penalty on Ralph de Broc too, who was [Robert’s] blood relative and no gentler in character, the originator of all malice, who raged like a wild beast against the archbishop’s men and household. And he made it clear to the people that the three bishops [of York, Salisbury, and London] lay under the same sentence, lest anyone communicate with such men, who had dared to challenge the injunction of kings, against the ancient statutes of Christ Church, Canterbury. In conclusion he declared, “Whoever sows hatred and discord between me and my lord the king, let them be accursed by Jesus Christ, and let the memory of them be blotted out from the assembly of the saints.” But those whom malice had already armed against the Lord’s anointed one were not at all afraid of the declaration of this terrible sentence.

Then the above-named bishops, entrusting themselves to the indignation of the king rather than to the judgment of God and the Church, quickly crossed the sea and went to the king, and bowing at his feet, with enough complaining speech to turn a hard heart, they deplored their suspension, telling how they had been treated by their lord of Canterbury . . . to the disgrace of the king and the kingdom. The accusers added that he would dare even more than he had so far, if the king were to bear such presumption patiently. Beset by such things, as if driven mad, scarcely containing himself in his frenzy, and not realizing what he was exclaiming, the king in the midst of repeated exchanges is said to have spoken thus: “I have nourished and promoted in my realm sluggish and wretched knaves who are faithless to their lord, and permit him to be tricked thus infamously by a low clerk!” He spoke, and withdrew from the midst of the colloquy, seeking a private place, to see whether solitude might ameliorate the madness he had conceived, and reflection might better cast out the raging poison he had swallowed. But his words were heard by four knights, distinguished in birth and members of the king’s own household, who fatally interpreted the meaning of the king’s words. Permitting no delay, and certainly urged on by one who was a murderer from the beginning, they conspired with one accord in the death of an innocent. And he who inspired the deed made it easy to perpetrate. For, leaving the king utterly ignorant, and embarking on a ship, at their prayer by favorable winds they were transported to England, landing at the “port of dogs” [Dover], and from then on they should be called miserable dogs, not knights. But the king did not know that the knights had departed. . . . But they were carried across the sea with such speed that they could not be recalled or caught by messengers before the sin was committed. It is clear enough from the consequences that their accursed and rash action was contrary to the king’s plan and will. For when the martyrdom of the venerable pontiff was announced, such confusion seized his mind, such sadness disturbed him, such unheard-of horror of the deed at the same time swallowed him up and possessed him, that no words can describe it. He tried to determine, since he was ignorant, whether in fact he might have called them back to thwart their purpose, either by custody in prison or any other method. But sometimes God’s providence, using evil men for good, thereby honors his beloved one more highly, whence human malice believes in this humility. In fact, human talent and skill are useless against the purpose of the Divinity. Surely it pleased the Savior to snatch from this misery, by martyrdom, one whom fullness of faith had made worthy of martyrdom.

As soon as they landed the said persons, who were not knights but miserable wretches, summoned the king’s officials whom the archbishop had excommunicated, and by dishonestly declaring that they were acting on the king’s orders and in his name they got together a band of followers. They gathered together, ready for any impious deed, and on the fifth day after the Nativity of Christ, that is on the day after the festival of the Holy Innocents [29 December], gathered together against the innocent. The hour of dinner being over, the saint had withdrawn with some of his household into an inner room to transact some business, leaving a crowd waiting outside in the hall. The four knights entered with one attendant. They were received with respect as the servants of the king and well known, and those who had waited on the archbishop, being now themselves at dinner, invited them to table. They scorned the food, thirsting rather for blood. By their order the archbishop was informed that four men had arrived from the king and wished to speak with him. He consented and they entered. They sat for a long time in silence and did not salute the archbishop or speak to him. Nor did the man of wise counsel salute them immediately when they came in, that according to the Scripture, “By your words you shall be justified” (Matthew 12:37), he might discover their intentions from their questions. After awhile, however, he turned to them, and carefully scanning the face of each one he greeted them in a friendly manner, but the wretches, who had made a treaty with death, answered his greeting with curses, and ironically prayed that God might help him. At this speech of bitterness and malice the man of God colored deeply, now seeing that they had come to harm him. Whereupon Fitz Urse, who seemed to be the chief among them and the most eager for crime, breathing fury, broke out in these words, “We have something to say to you by the king’s command: say if you wish us to say it here before everyone.” But the archbishop knew what they were going to say, and replied, “These things should not be spoken in private or in the chamber, but in public.” Now these wretches so burned for the slaughter of the archbishop that if the door-keeper had not called back the clerks—for the archbishop had ordered them all to go out—they would have killed him, as they afterward confessed, with the shaft of his cross which stood nearby. When those who had gone out returned, he, who had before thus reviled the archbishop, said, “When peace was made between you and all disputes were ended, the king sent you back free to your own see [the bishop’s area of jurisdiction], as you demanded: but you on the other hand, adding insult to your former injuries, have broken the peace and done evil to your lord. For those by whose ministry the king’s son was crowned and invested with the honors of sovereignty, you, with obstinate pride, have condemned by sentence of suspension, and you have also bound with the chain of anathema those servants of the king by whose prudent counsels the business of the kingdom is transacted. From this it is manifest that you would take away the crown from the king’s son if you could. Now the plots and schemes you have laid to carry out your designs against the king are known to all. Say, therefore, if you are ready to answer for these things in the king’s presence, for this is why we have been sent.” The archbishop answered them, “Never was it my wish, as God is my witness, to take away the crown from my lord the king’s son, or diminish his power; rather would I wish him three crowns, and would help him obtain the greatest realms of the earth with right and equity. But it is not just for my lord the king to be offended because my people accompany me through the cities and towns, and come out to meet me, when they have for seven years been deprived of the consolation of my presence; and even now I am ready to satisfy him wherever my lord pleases, if I have done anything wrong; but he has forbidden me with threats to enter any of his cities and towns, or even villages. Moreover, the prelates were suspended from their office not by me, but by the lord pope.” “It was through you,” said the madmen, “that they were suspended. Absolve them.” “I do not deny,” he answered, “that it was done through me, but it is beyond my power, and utterly incompatible with my position that I should absolve those whom the pope has bound. Let them go to him, on whom reflects the contempt they have shown toward me and their mother, the church of Christ at Canterbury.”

“Now,” said these butchers, “the king commands you to depart with all your men from the kingdom, and the land which lies under his sway: for from this day on there can be no peace with you, or any of yours, for you have broken the peace.” Then he said, “Let your threats cease and your wranglings be stilled. I trust in the king of heaven, who for his own suffered on the Cross: for from this day no one shall see the sea between me and my church. I did not come here to flee; he who wants me shall find me here. And it does not befit the king to so command me; the insults which I and mine have received from the king’s servants are sufficient, without further threats.” “Thus did the king command,” they replied, “and we will make it good, for whereas you ought to have shown respect to the king’s majesty, and submitted your vengeance to his justice, you have followed the impulse of your passion and basely thrust from the church his ministers and servants.” At these words Christ’s champion, rising in fervor of spirit against his accusers, exclaimed, “Whoever shall presume to violate the decrees of the sacred Roman see or the laws of Christ’s church, and shall refuse to make satisfaction, I will not spare him, whoever he may be, nor will I delay to inflict ecclesiastical censures on the delinquents.”

Confounded by these words the knights sprang up, for they could bear his firmness no longer, and coming close to him they said, “We declare to you that you have spoken in peril of your head.” “Do you come to kill me?” he answered, “I have committed my cause to the judge of all; and so I am not moved by threats, nor are your swords more ready to strike than my soul is for martyrdom. Seek him who flees from you; me you will find foot to foot in the battle of the Lord.” As they went out with tumult and insults, he who was fitly surnamed Ursus [meaning bear], called out in a brutal way, “In the king’s name we order you clerks and monks to take and hold that man, lest he escape by flight before the king has full justice on his body.” As they went out with these words, the man of God followed them to the door and exclaimed, “Here, here you shall find me,” putting his hand over his neck as though showing the place where they were to strike. He returned then to the place where he had sat before, and consoled his clerks, and exhorted them not to fear; and, as it seemed to us who were present, waited as unperturbed—though they sought to slay him alone—as though they had come to invite him to a wedding. Before long back the butchers returned with swords and axes and falchions [single-edged swords] and other weapons fit for the crime which their minds were set on. When they found the doors barred and they were not opened to their knocking, they turned aside by a private way through the orchard to a wooden partition which they cut and hacked till they broke it down. The servants and clerks were horribly frightened by this terrible noise, and, like sheep before the wolf, dispersed here and there. Those who remained called out that he should flee to the church, but he did not forget his promise not to flee from his murderers through fear of death, and refused to go. . . . He who had long sighed for martyrdom now saw that, as it seemed, the occasion had now come, and feared lest he should delay it or put it away altogether if he went into the church. But the monks were insistent, declaring that it were not fit for him to be absent from vespers, which were at that moment being performed. He remained immoveable in that place of less reverence, for he had now in his mind caught a sight of the hour of happy consummation for which he had sighed so long, and he feared lest the reverence of the sacred place should deter even the impious from their purpose, and cheat him of his heart’s desire. . . . But when he would not be persuaded by argument or prayer to take refuge in the church, the monks caught hold of him in spite of his resistance, and pulled, dragged, and pushed him, not heeding his protests, and brought him to the church. . . .

When the holy archbishop entered the church, the monks stopped the vespers which they had begun and ran to him, glorifying God at the sight of their father, whom they had heard was dead, alive and safe. They hastened, by bolting the doors of the church, to protect their shepherd from the slaughter. But the champion, turning to them, ordered the church doors to be thrown open, saying, “It is not meet to make a fortress of the house of prayer, the Church of Christ: even if it is not shut up, it is still able to protect its own, and we shall triumph over the enemy in suffering rather than in fighting, for we came to suffer, not to resist.” And straightway, they entered the house of peace and reconciliation with swords sacrilegiously drawn, striking horror in the beholders’ hearts by their very looks and the clanging of their arms. . . .

Inspired by fury the knights called out, “Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the king and realm?” When he did not answer, they cried out the more furiously, “Where is the archbishop?” At this, intrepid and fearless, as it is written, “the just, like a bold lion, shall be without fear” (cf. Proverbs 28:1) he descended from the stair where he had been dragged by the monks in fear of the knights, and in a clear voice answered, “I am here, no traitor to the king, but a priest. Why do you seek me?” And whereas he had already said that he did not fear them, he added, “So I am ready to suffer in his name, who redeemed me by his blood: far be it from me to flee from your swords, or to depart from justice.” Having spoken thus, he turned to the right, under a pillar, having on one side the altar of the blessed Mother of God and ever Virgin Mary, on the other that of Saint Benedict the Confessor, by whose example and prayers, having crucified the world with its lusts, he bore all that the murderers could do with such constancy of soul as if he were no longer in the flesh. The murderers followed him. “Absolve,” they cried, “and restore to communion those whom you have excommunicated, and restore their powers to those whom you have suspended.” He answered, “There has been no satisfaction, and I will not absolve them.” “Then you shall die,” they cried, “and receive what you deserve.” “I am ready,” he replied, “to die for my Lord, that in my blood the Church may obtain liberty and peace. But in the name of almighty God, I forbid you to hurt my people, whether clerk or lay.” Thus piously and thoughtfully did the noble martyr ensure that no one near him should be hurt, nor the innocent be brought to death, whereby his glory should be dimmed as he hastened to Christ. . . . Then they laid sacrilegious hands on him, pulling and dragging him so that they might kill him outside the church, or carry him away as a prisoner, as they afterward confessed. But when he could not be forced away from the pillar, one of them pressed on him and clung to him more closely. He pushed him off calling him “pimp,” and saying, “Touch me not, Reginald, you who owe me fealty and subjection; you and your accomplices are acting like madmen.” The knight, fired with terrible rage at this severe repulse, waved his sword over the sacred head. “No faith,” he cried, “nor subjection do I owe you against my fealty to my lord, the king.” Then the unconquered martyr, seeing the hour at hand which should put an end to this miserable life and straightaway give him the crown of immortality promised by the Lord, inclined his neck as one who prays and joining his hands he lifted them up, and commended his cause and that of the Church to God, to Saint Mary, and to the blessed martyr Saint Denis. Scarce had he said the words than the wicked knight, fearing lest he should be rescued by the people and escape alive, leapt upon him suddenly and wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God on the head, cutting off the top of the crown which the sacred unction of the chrism had dedicated to God, and by the same blow he wounded the arm of him who tells this. For he [Edward Grim], when the others, both monks and clerks, fled, stuck close to the sainted archbishop and held him in his arms until the one he interposed was almost severed. Behold the simplicity of the dove, the wisdom of the serpent, in the martyr who opposed his body to those who struck that he might preserve his head, that is his soul and the Church, unharmed, nor would he use any means to escape from those who destroyed his body. O worthy shepherd, who gave himself so boldly to the wolves that his flock might not be torn! Because he had rejected the world, the world, wishing to crush him, unknowingly exalted him. Then he received a second blow on the head but still stood firm. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows, offering himself a living victim, and saying in a low voice, “For the name of Jesus and the protection of the Church I am ready to embrace death.” Then the third knight inflicted a terrible wound as he lay, by which the sword was broken against the pavement, and the crown which was large was separated from the head, so that the blood, white with the brain, and the brain, red with blood, dyed the surface of the virgin mother Church with the life and death of the confessor and martyr in the colors of the lily and the rose. The fourth knight prevented anyone from interfering so that the others might freely perpetrate the murder. As for the fifth, no knight but that clerk who had entered with the knights, so that the martyr who was in other things like Christ would not lack a fifth blow, he put his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr, and, horrible to say, scattered his brains and blood over the pavement, calling out to the others, “Let us away, knights, he will rise no more.”

Miracles of Saint Thomas, by William of Canterbury

Of a matron who on the seventh day spoke with the martyr in her sleep

Seven days had passed since the death of the martyr. A certain freeborn woman, wife of one Ralph, a man of honor according to this world, was resting on her bed at home. This woman, hearing of the death of the martyr, began to be somewhat sad, mourning as a good sheep for the death of a kind shepherd, for the dishonor to the Church and the wickedness of the crime. Because of this sorrow she obtained the honor of seeing a vision in her sleep. Upon entering her place of prayer she found a man standing before the altar, wearing a hood and clad in white, as though he were performing the divine service. When he saw her he seated himself near the southern part of the room, nodding familiarly to her as if seeking to ask that she draw nearer. She asked what she could do to gain salvation for her soul. He replied, “Every week the sixth day must be observed as a fast day by you, and when you have passed a year in this way come to me.” Then he added, “Do you know who it is with whom you are conversing?” “You are the one,” she answered, “whom those four wicked men presumed to murder with such insolent boldness.”

Of a townsman whom the martyr suddenly snatched from this world, because he had snatched a poor woman’s sheep

A rich man named Ralph, of the town of Nottingham, detained some few sheep of a poor woman. This latter begged to be permitted to buy them back, saying, “Grant this kindness, I beg, my master, to your handmaid, that I may receive back my sheep, provided I pay eight pieces of silver for each one.” He refused, since he wished to keep those sheep she owned for himself. Hear what happened, in order that you may not be enticed to become rich from the goods of another. He was riding along on his pacer, snapping a switch which he was carrying in his hand. The woman pressed him that she might have the property which was really hers by paying for it. “Do not hinder my journey, my master,” said she; “I have planned to go to the holy martyr Thomas, and I have destined the wool of my sheep to pay my expenses on the way. Show mercy to me, that the martyr may do the same to you.” Hearing this he looked down at her, calling out in terrible tones, “Depart, you low and worthless slave, I shall do nothing for you.” She kept urging him, adding prayers to her money; but seeing that she gained nothing either from prayers or money, she ended with a curse. “May the curse of God and of the martyr Thomas fall on this man who has robbed me of my own property.” At this word the rich man, struck by the divine hand, fell heavily forward on the pommel of his saddle, where, groaning, he moaned, “I die,” for the blow had stopped his breath.

Of a girl who had sunk in some water

Thanks be to God, who glorifies his martyr Thomas everywhere. In Normandy there was a little girl, Hawisia, daughter of a peasant of the village of Grochet, who, as she was wandering along in her thoughtless childish way, fell into a pond. She was only two years and three months old. When she was not found by her mother the next day or the day following that, she was sought for and found in the pool. The mother, crying out, ran to her, while the father hastened to her all dripping as she was, and, seizing her, held her by the feet. The neighbors came running up and she was pronounced dead. But at the advice of a priest she was dedicated to the holy martyr Thomas, and she was restored to life the instant the vow was made.

Questions: How did Becket’s death come about? What was his own role in it? How did contemporaries view him, both before and after his death? What is Edward Grim’s attitude toward the archbishop and toward the king? How would Thomas of Canterbury’s stories have helped spread devotion to Thomas’s cult? What do the miracles tell us about medieval life and beliefs?

36. Glanville’s Treatise on the Laws and Customs of the Kingdom of England

In the 1180s a treatise describing English civil law was written by someone familiar with the procedures of the royal courts and with Henry II’s reforms; the name of the then-justiciar Ranulf Glanville has traditionally been attached to this work, though there is little evidence supporting his authorship. By far the greatest concern of the civil law was title to land. The excerpts below describe some traditional aspects of land law (dower and inheritance customs) and some of Henry II’s innovations (the Grand Assize). The sample writs that the author includes in the treatise have been omitted.

Source: trans. J. Beames, A Translation of Glanville, ed. J.H. Beale (Washington: John Byrne & Company, 1900), pp. 31, 35–37, 39–42, 44–46, 48–55, 91–105, 113–16, 124–28, 133–36, 138–47, 149–50; revised.

Book 2. . . . Of Those Things Which Appertain to the Duel or Grand Assize

3. . . . The demand and claim of the demandant being thus made, the tenant shall have the choice of either defending himself against the demandant by the duel, or putting himself upon the king’s Grand Assize, and requiring a recognition to ascertain which of the two has the greater right to the land in dispute.

. . . But here we should observe, that after the tenant has once waged the duel he must abide by his choice, and cannot afterward put himself upon the Assize. . . . All the delays which can with propriety be resorted to having expired, it is requisite that before the duel can take place, the demandant should appear in court, accompanied by his champion armed for the contest. Nor will it suffice, if he then produce any other champion than one of those whom he has engaged to prove his claim: neither, indeed, can any other contend for him, after the duel has been once waged. . . .

The duel being finished, a fine of 60s. shall be imposed upon the conquered party, in the name of recreantise [acknowledgment of defeat], besides which he shall lose his law; and if the champion of the tenant should be conquered, his principal shall lose the land in question, with all the fruits and produce found upon it at the time of the seisin of the fee, and never again shall a complaint concerning the same land be heard in court. For those matters which have been once determined in the king’s court by duel remain forever after unalterable. Upon the determination of the suit, let the sheriff be commanded by the following writ to give possession of the land to the successful party. . . .

6. But, if the tenant should prefer putting himself upon the king’s Grand Assize, the demandant must either adopt the same course or decline it. If the demandant has once conceded in court that he would put himself upon the Assize, and has so expressed himself before the Justices of the Common Pleas, he cannot afterward retract, but ought either to stand or fall by the Assize.

If he objects to putting himself upon the Grand Assize, he ought in such case to show some cause why the Assize should not proceed between them. . . .

7. The Grand Assize is a certain royal benefit bestowed upon the people, and emanating from the clemency of the prince, with the advice of his nobles. So effectually does this proceeding preserve the lives and civil condition of men, that every one may now possess his right in safety, at the same time that he avoids the doubtful event of the duel. Nor is this all: the severe punishment of an unexpected and premature death is avoided, or at least the opprobrium of a lasting infamy, of that dreadful and ignominious word that so disgracefully resounds from the mouth of the conquered champion.

This legal institution flows from the most profound equity. For that justice, which after many and long delays is scarcely, if ever, elicited by the duel, is more advantageously and expeditiously attained through the benefit of this institution. This Assize, indeed, allows not so many delays as the duel, as will be seen in the sequel. And by this course of proceeding, both the labor of men and the expenses of the poor are saved. Besides, by so much as the testimony of many credible witnesses, in judicial proceedings, preponderates over that of only one, by so much greater equity is this institution regulated than that of the duel. For since the duel proceeds upon the testimony [the combat] of one juror, this constitution requires the oaths of at least twelve lawful men.

These are the proceedings which lead to the Assize. The party who puts himself upon the Assize should, from the first, . . . sue out a writ for keeping the peace. . . .

10. By means of such writs, the tenant may protect himself, and may put himself upon the Assize, until his adversary, appearing in court, pray another writ, in order that four lawful knights of the county, and of the neighborhood, might elect twelve lawful knights from the same neighborhood, who should say, upon oath, which of the litigating parties has the greater right to the land in question. . . .

12. . . . [Because of the large number of possible delays,] a certain just constitution has been passed, under which the court is authorized to expedite the suit, upon the four knights appearing in court on the appointed day, and being prepared to proceed to the election of the twelve knights. . . . But, if the tenant himself be present in court, he may possibly have a just cause of exception against one or more of the twelve knights, and concerning this he should be heard in court. It is usual, indeed, for the purpose of satisfying the absent party, not to confine the number to be elected to twelve, but to comprise as many more as may incontrovertibly satisfy such absent party, when he returns to court. . . .

Indeed, if the object is to expedite the proceedings, it will more avail to follow the direction of the court, than to observe the accustomed course of the law. It is, therefore, committed to the discretion and judgment of the king or his justices, to temper the proceeding so as to render it more beneficial and equitable. . . .

14. The election of the twelve knights having been made, they should be summoned to appear in court, prepared upon their oaths to declare which of them, namely, the tenant or the demandant, possesses the greater right to the property in question. Let the summons be made by the following writ. . . .

16. On the day fixed for the attendance of the twelve knights to take the recognition, whether the tenant appears or absent himself, the recognition shall proceed without delay. . . .

17. When the Assize proceeds to make recognition, the right will be well known either to all the jurors, or some may know it and some not, or all may be alike ignorant concerning it. If none of them are acquainted with the truth of the matter, and this be testified upon their oaths in court, recourse must be had to others, until such can be found who do know the truth of it. Should it, however, happen that some of them know the truth of the matter, and some not, the latter are to be rejected, and others summoned to court, until twelve, at least, can be found who are unanimous. But, if some of the jurors should decide for one party, and some of them for the other, then others must be added, until at least twelve can be found who agree in favor with one side. Each of the knights summoned for this purpose ought to swear that he will neither utter that which is false, nor knowingly conceal the truth. With respect to the knowledge requisite on the part of those sworn, they should be acquainted with the merits of the cause, either from what they have personally seen and heard, or from the declarations of their fathers or other equally creditable sources, as if falling within their own immediate knowledge.

18. When the twelve knights . . . entertain no doubt about the truth of the thing, then the Assize must proceed to ascertain whether the demandant or the tenant has the greater right to the subject in dispute.

But if they decide in favor of the tenant, or make any other declaration by which it should sufficiently appear to the king or his justices that the tenant has greater right to the subject in dispute, then, by the judgment of the court, he shall be . . . forever released from the claim of the demandant, who shall never again be heard in court concerning the matter. For those questions which have once been lawfully determined by the king’s Grand Assize cannot with propriety be revived on any subsequent occasion. But if by this Assize it be decided in court in favor of the demandant, then his adversary shall lose the land in question, which shall be restored to the demandant, together with all the fruits and produce found upon the land at the time of seisin. . . .

Book 6. Of Dower

1. The term dower is used in two senses. Dower, in the sense in which it is commonly used, means that which any free man, at the time of his being affianced, gives to his bride at the church door. For every man is bound by the ecclesiastical as well as the secular law to endow his bride at the time he is affianced to her. When a man endows his bride, he either names the dower, or not. In the latter case, the third part of all the husband’s freehold land is understood to be the wife’s dower; and the third part of all such freehold lands as her husband held at the time of affiancing, and of which he was seised in his demesne, is termed a woman’s reasonable dower. If, however, the man names the dower, and mentions more than a third part, such designation shall not avail, as far as it applies to the quantity. It shall be reduced by apportionment to the third part; because a man may endow a woman of less, but cannot endow her of more than a third part of his land.

2. Should it happen, as it sometimes does, that a man endows a woman, having but a small freehold at the time of his being affianced, he may afterward enlarge her dower to the third part or less of the lands he may have purchased.

But if upon the assignment of dower, no mention was made concerning purchases, even admitting that at the time of affiancing he possessed but a small estate, and that he afterward much increased it, the wife cannot claim as dower more than a third part of such land as her husband held at the time of being affianced, and when he endowed her. The same rule prevails if a man, not being possessed of any land, should endow his wife with his chattels, and other things, or even with money. Should he afterward make considerable purchases in land and tenements, the wife cannot claim any part of such property so acquired by purchase; it being, with respect to the quantity or quality of the dower assigned to any woman, a general principle, that if she is satisfied to the extent of her endowment at the door of the church, she can never afterward claim as dower anything beyond it.

3. It is understood that a woman cannot make any disposition of her dower during the lifetime of her husband. For since the wife herself is in a legal sense under the absolute power of her husband, . . . the dower, as well as the woman herself and all things belonging to her, should be considered to be fully at the disposal of the husband. . . .

4. Upon the death of the husband of a woman, her dower, if it has been named, will either be vacant or not.

In the former case, the woman may, with the consent of the heir, enter upon her dower, and retain the possession of it. If, however, the dower be not vacant, either the whole will be so circumstanced, or some part will be vacant, and some not. If a certain part be vacant, and a certain part not, she may pursue the course we have described, and enter into the part which is vacant; and for the residue, she shall have a writ of right, directed to her warrantor [her husband’s heir], in order to compel him to do complete justice concerning the land which she claims as appertaining to her reasonable dower. . . .

6. The plea shall be discussed in the court of the warrantor by virtue of this writ, until it be proved that such court has failed in doing justice. . . . Upon proof of this, the suit shall be removed into the county court, through the medium of which the suit may, at the pleasure of the king or his chief justiciary, be lawfully transferred to the king’s court. . . .

8. Pleas of this description, as, indeed, some others, may be transferred from the county court to the supreme court of the king for a variety of causes: as, on account of any doubt which may arise in the county court concerning the plea itself, and which that court is unable to decide. . . . Upon the day appointed in court, either both parties will be absent, or only one will be, or both will appear. . . . If both be present in court, the woman shall set forth her claim against her adversary in the following words: “I demand such land, as appertaining to such land as was named to me in dower, and of which my husband endowed me at the door of the church, the day he espoused me, as that of which he was invested and seised at the time when he endowed me.”

Various are the answers which the adverse party usually gives to a claim of this kind; in substance, however, he will either deny that she was so endowed, or concede it.

But, whatever he may allege, the suit ought not to proceed without the heir of the woman’s husband. He shall, therefore, be summoned to appear in court to hear the suit, by the following writ. . . .

Should the heir, after having been summoned, neither appear, nor essoin himself [give a legal excuse for not appearing], on the first, second, nor third day; or if, after having cast the usual essoins, he should on the fourth day neither appear nor send his attorney, there may be a question of how he ought to be, or can be, distrained, consistently with the law and custom of the realm. In the opinion of some, his appearance in court shall be compelled by distraining his fee. And [they think] that, therefore, by the direction of the court so much of his fee shall be taken into the king’s hands as may be necessary to distrain him to appear in court to show whether he ought to warrant [guarantee to the woman] the land in question or not. Others think that his appearance in court for such purpose may be obtained by attaching him with pledges.

11. When, at last, the heir of the husband of the woman, the complainant, appears in court, either he will affirm the fact, and concede that the land in question appertains to the dower of the woman, . . . or he will deny it. If the heir admits this in court, he shall then be bound to recover the land against the tenant, if [the tenant] be disposed to dispute the matter, and then deliver it to the woman; and thus the contest will be changed into one between the tenant and the heir.

If, however, the heir be unwilling to contest the point, he shall be bound to give to the woman a fair equivalent; because the woman herself shall not afterward sustain any loss. But, if the heir himself neither admit nor concede to the woman that which she alleges against the tenant, then the suit may proceed between the woman and the heir . . . [and] the matter may be decided by the duel, provided the woman produces in court those who heard and saw the endowment, or any proper witness who may have heard and seen the fact of her being endowed by the ancestor of the heir at the church door, at the time of the espousals, and be ready to prove such fact against him.

Should the woman prevail against the heir in the duel, then the heir shall be bound to deliver the land in question to the woman, or to give her an adequate recompense.

Questions: What options are available for settling a land dispute? Why would the crown encourage litigants to use the Grand Assize rather than settle disputes via trial by combat? What were the advantages and disadvantages of widowhood? Can you deduce the reasons for laws regarding wills and heirs? What do these laws reveal about the legal status of women?

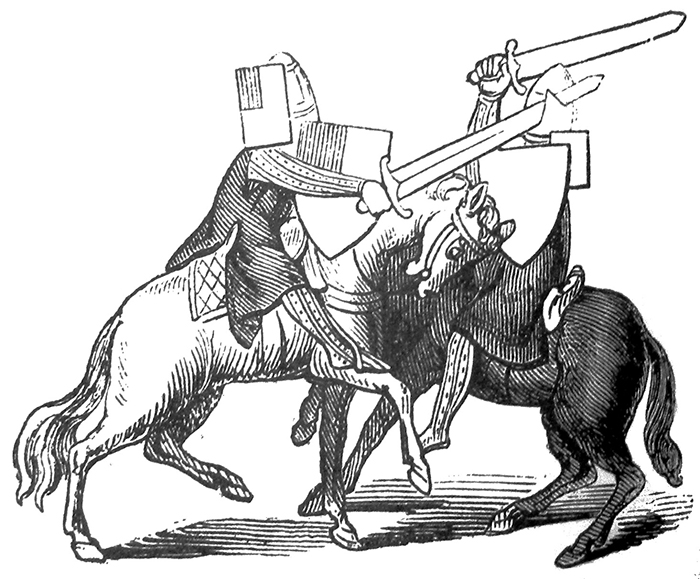

37. Jocelin of Brakelond on the Misfortunes of Henry of Essex

Henry of Essex was a locally important baron and, in the 1150s, a royal constable. While we know a fair amount about him from record sources, this narrative account of his life, found in a monastic chronicle, is unusual for a layman. Though short, it sheds light on many aspects of medieval life. The duel in this story represents the normal method of deciding a judicial dispute between two vassals in their lord’s court—in this case, two barons in the court of their lord, King Henry II, in 1163. It is perhaps relevant that Robert de Montfort, Henry of Essex’s accuser, had a competing claim to Henry’s castle and lands at Haughley, which Robert’s family had lost during the reign of Henry I.

Source: trans. L.C. Jane, The Chronicle of Jocelin of Brakelond, Monk of St. Edmundsbury: A Picture of Monastic and Social Life in the XIIth Century (London: Chatto and Windus, 1907), pp. 108–12; revised.

When the abbot had come to Reading, and we with him, we were rightly received by the monks of that place. And among them was Henry of Essex as a professed monk, who, when he had a chance to speak to the abbot and to those who were present, told us how he had been conquered in a trial by battle, and how and why Saint Edmund confounded him in the very hour of conflict. I wrote down his tale by command of the lord abbot, and I wrote it also in these words.

Inasmuch as it is impossible to avoid unknown evil, we have thought it well to commit to writing the acts and crimes of Henry of Essex, that they may be a warning, and not an example. Stories often convey a useful and salutary warning.

The said Henry, then, while he enjoyed great prosperity, had the reputation of a great man among the nobles of the realm, and he was renowned by birth, noted for his deeds of arms, the standardbearer of the king, and feared by all men owing to his might. And when others who lived near him enriched the church of the blessed king and martyr Edmund [the monastery at Bury Saint Edmunds] with goods and rents, he on the contrary not only shut his eyes to this fact, but further violently, and wrongfully, and by injuries took away the annual rent of five shillings, and converted it to his own use.

In the course of time, moreover, when a case arose in the court of Saint Edmund concerning a wrong done to a certain maiden, the same Henry came there, and protested and declared that the trial ought to be held in his court because the place where the said maiden was born was within his lordship of Lailand. With the excuse of this affair, he dared to trouble the court of Saint Edmund for a long while with journeyings and countless charges.

But fortune, which had assisted his wishes in these and other like matters, brought upon him a cause for lasting grief, and after mocking him with a happy beginning, planned a sad conclusion for him; for it is the custom of fortune to smile, that she may rage; to flatter, that she may deceive; and to raise up only that she may cast down. For presently there rose against him Robert de Montfort, his relative, and a man not unequal to him in birth and power, and slandered him in the presence of the princes of the land, accusing him of treason to the king. For he asserted that Henry, in the course of the Welsh war [in 1157], in the difficult pass of Coleshill, had treacherously cast down the standard of the lord king, and proclaimed his death in a loud voice; and that he had induced those who were coming to the help of the king to turn in flight. As a matter of fact, the said Henry of Essex believed that the renowned King Henry II, who had been caught in an ambush by the Welsh, had been slain, and this would have been the truth, had not Roger, earl of Clare, a man renowned in birth and more renowned for his deeds of arms, quickly rushed up with his men of Clare, and raised the standard of the lord king, which revived the strength and courage of the whole army.

Then Henry resisted the said Robert in the council, and utterly denied the charge, so that after a little while, [in 1163] the matter came to a trial by battle. Then when they met at Reading to fight on an island somewhat near the abbey, a multitude of persons also gathered there to see how the affair would end. And it came to pass, that when Robert manfully made his armor ring again with hard and frequent blows, and his bold beginning promised the fruit of victory, Henry’s strength began to fail him a little. And as he looked round about, behold! on the edge of land and water, he saw the glorious king and martyr Edmund, armed and, as it were, flying through the air, and looking toward him with an angry countenance, often shaking his head in a threatening manner, and showing himself full of wrath. And Henry also saw with the saint another knight, Gilbert de Cereville, who appeared not only less than the saint in point of dignity, but also head and shoulders shorter; and he looked on him with accusing and angry glances. This Gilbert, afflicted with bonds and tortures by order of the said Henry, had died, as the result of an accusation brought against him by Henry’s wife, who cast the penalty for her own illdoing on an innocent man, and said that she could not endure the evil suggestions of the said Gilbert.

When he saw these sights, then, Henry grew alarmed and fearful, and called to mind that an old crime brings new shame. And now, giving up all hope, and abandoning skillful fighting for a blind rush, he took the part of one who attacks rather than that of one who defends himself. And when he gave hard blows, he received harder; and while he fought manfully, he was more manfully resisted. In a word, he fell conquered.

And as he was thought to be dead, in accordance with the earnest request of the magnates of England, the relatives of the said Henry, the monks of that place were allowed to give burial to his corpse. But he afterward revived, and when he had regained the blessing of health, under the regular habit of a monk, he wiped out the stain of his former life, and taking care to purify the long week of his dissolute past with at least one sabbath, he cultivated the study of the virtues, to bring forth the fruit of happiness.

Questions: What were Henry’s “crimes?” How does the monastic context shape the story of Henry’s life? From a non-religious perspective, what brought about Henry’s downfall?

38. The Political Career of Eleanor of Aquitaine

Married to the future Henry II in 1152, soon after the dissolution of her marriage to the French king Louis VII, Eleanor of Aquitaine helped rule England for decades, first as Henry’s queen and regent in Aquitaine, and later as an advisor to her sons Richard I (r. 1189–99) and John (r. 1199–1216). The first letter below is thought to have been written by Peter of Blois, a clerk in the service of Archbishop Rotrou of Rouen, at the archbishop’s behest, after Henry II’s three eldest sons, encouraged and supported by Eleanor, rose in rebellion against their father. In an interesting twist, twenty years later Peter of Blois also wrote the second letter, one of three sent in Eleanor’s name to Pope Celestine III during King Richard I’s captivity following the Third Crusade. While Eleanor (like all twelfth-century elites) did not write her own letters, this document certainly expresses her anger and frustration at what she felt to be the papacy’s inaction during her son’s thirteen-month-long captivity.

Source: trans. K.A. Smith from Patrologia cursus completus, series latina, ed. J.-P. Migne (Paris: Migne, 1844–64), vol. 207, cols. 448–49; vol. 206, cols. 1262–65.

[Peter of Blois, writing on behalf of ] Archbishop Rotrou of Rouen, to Queen Eleanor, 1173

To the queen of England, the archbishop of Rouen and his suffragen bishops send their greetings in the search for peace. It is publicly known—and indeed, no Christian can be allowed to ignore this fact—that marriage is a firm and indissoluble union. Those who have been joined together in marriage cannot be separated. This is confirmed by sacred truth, which cannot lie: as it is written, “What God has joined together, let no man put asunder (Matthew 19:6).” Just as anyone who separates spouses breaks the divine command, so, too, does the wife who separates herself from her husband and disregards the faith of this social bond. When two spouses are made one in the flesh, a spiritual union necessarily follows from their bodily union and common consent. A woman who is not subject to a man defies the natural order of things as well as the injunction of the Gospel. For “the woman’s head is the man” (1 Corinthians 11:3), from whose flesh she was made; she is joined to the man, and subject to the man’s authority. And so we are deeply grieved by the well-known and lamentable charge against you, a most prudent woman who has nonetheless abandoned her husband. [Such a woman] has forsaken his side, the body’s limb has turned against its head; even worse, you have encouraged the lord king’s children, who are also yours, to rebel against their father. It is fitting to echo the words of the prophet, who said, “I have brought up children and exalted them, but they have despised me (Isaiah 1:2).” Would that, as another prophet lamented, our life would reach its final hour and the face of the earth would swallow us so that we would not have to witness such evil! Because we know that if you do not return to your husband, there will be destruction everywhere, and what is now your sin alone will soon be shared by the entire kingdom. And so, illustrious queen, return to your husband and our lord; convert turmoil into peace through your reconciliation and restore universal happiness through your return. If you are not moved to do this by our prayers, at least take heed of the suffering of your people, the looming oppression of the Church and the destruction of the kingdom. For either truth lies, or “every kingdom divided against itself shall be brought to desolation (Luke 11:17).” The lord king himself cannot bring this desolation to an end; his sons and heirs—who have been led by your feminine hand and boyish council to rebel against this king, to whom the mightiest kings have bowed their necks. Before things get any worse, you and your sons must return to your husband, whom you are bound to obey and to live with. Repent, or you and your sons will be held in suspicion. We are very certain that he will receive you with love and ensure your safety. I beseech you to warn your sons to submit and show their love for their father, who has suffered so much anguish, so much persecution, so much illness. Lest rash actions waste and destroy what has been built up with so much sweat, we say these words to you, most pious queen, in zeal for God and with a feeling of sincere love. After all, you and your husband are both our parishioners. We cannot desert the cause of justice.

Unless you return to your husband we will be bound by canon law to use ecclesiastical authority to censure you. We will be bound to do this, albeit unwillingly, and with sorrow and tears, if you do not regain your senses. Farewell.

Queen Eleanor to Pope Celestine III, 1193

To the reverend father and lord Celestine, pope by the grace of God. Eleanor, by the wrath of God queen of the English, duchess of the Normans, and countess of the Angevins, begs him to show himself to be a father to her, a miserable mother.

I had determined to remain silent, lest through the fullness of my heart and the violence of my grief I might utter any imprudent word against you, the prince of the priesthood, and be blamed for my insolence and presumption. The violent onset of grief is not unlike madness: it does no homage to princes, pays no respect to allies, it defers to no one and spares no one, not even itself. No one should be surprised, then, if the strength of my grief has roughened my words, for I mourn a public loss even as a private grief has taken root in my innermost spirit. . . . The nations are divided, the peoples torn apart, lands laid waste, and the whole of the Latin Church moved in a spirit of contrition and humility to lament and beseech you, whom God has placed over the peoples and kingdoms in the fullness of power. We hope that the cries of the afflicted will reach your ears, for our troubles are multiplied beyond number (cf. Psalm 39:14). Nor can you plead ignorance of that crime and infamy, since you are the vicar of the crucified, the successor of Peter, the priest of Christ, the chosen one of God, the God even of Pharoah.

. . . If the Roman Church can sit by with clasped hands and silently bear such injuries to Christ, “let God arise” (Psalm 67:1) and judge our cause and “look on the face of Christ (Psalm 83:10).” Where is the zeal of Elias against Ahab? Of John the Baptist against Herod? Of Ambrose against Valentinian? Of Pope Alexander III who, as we saw and heard, solemnly and terribly used the full power of the apostolic see to cut off Frederick [Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor], the father of this prince [Henry VI] from the communion of the faithful? In the future such a tyrant will scorn the apostolic keys and hold the law of God to be empty words. Against such an enemy you must firmly take up “the sword of the spirit, which is the word of God (Ephesians 6:17).” For it is written, “He that despises you, despises me (Luke 10:16).” And so, if you do not wish any injury to be done to yourself or to the Roman Church, you cannot pretend not to know of Saint Peter’s shame and Christ’s injury. Do not keep the word of God prisoner in your mouth, lest through your human fear the spirit of liberty be overthrown. It is better to fall into the hands of men than to desert God’s law.

. . . How can you balance the good books of justice, you whom Henry [II] of blessed memory, father of that king [Richard], sustained with much needed aid during that schism, and supported against the hostile tyranny of Frederick [Barbarossa] when he harrassed you and your faithful supporters and threatened the possessions of the Roman Church? When Frederick, instigator of schism and author of resistance to Pope Alexander III who was, as you know, canonically elected, vowed his support for the apostate Octavian [a rival pope]. While the Church was suffering through the upheaval of that schism in every land, the kings of England and France received embassies from each party. And when the French king’s counselors wavered, doubtfully hesitating over which party they should support, King Henry, grieving that Christ’s tunic should be torn in two, was the first to favor Pope Alexander, and he brought the French king over to his side with many admonitions and words of advice; thus he delivered the ship of Saint Peter from shipwreck and brought it to a safe harbor. We witnessed these things with our own eyes. . . . If, therefore, ingratitude could ever efface the memory of such a favor, it would greatly dishonor the glory of the apostolic see.

Questions: What assumptions about gender roles and queenship are expressed in the first letter? Given the tone of the second letter, how might Eleanor have responded to the archbishop’s scolding? How does Eleanor attempt to enlist Pope Celestine III’s help in freeing her son Richard from captivity? In what ways does she assert her own authority here?

39. The Cult of King Arthur

The cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth’s hugely influential History of the Kings of Britain laid the foundation for the elaboration of Arthurian legends by later English writers. A patriotic work of myth-history, the History celebrates the heroic exploits of Arthur, greatest of Britain’s kings. Geoffrey completed his work ca 1136, dedicating it to the earl of Gloucester Robert Fitzroy, whose nephew Henry II came to rule an enormous Angevin “empire,” the parameters of which recalled Arthur’s own. In the second text, Gerald of Wales credits Henry II with inspiring the exhumation of Arthur’s body at Glastonbury Abbey. Ca 1191, at a moment of financial crisis for the abbey, its monks claimed to have discovered the skeletons of a huge man and a woman, along with a lead cross identifying these as Arthur and Guinevere. The monks interred these remains in their church, where they became a very popular and profitable attraction for pilgrims.

Sources: Geoffrey of Monmouth, Histories of the Kings of Britain, trans. Sebastian Evans (London: J.M. Dent & Company, 1904), pp. 226–27, 240, 287–92, revised; Gerald of Wales, De instructione principis, in Geraldi Cambrensis Opera, ed. George F. Werner, trans. K.A. Smith (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1891), vol. 8, pp. 126–29.

[Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Account of Arthur’s Reign]

After the death of Uther Pendragon, the barons of Britain came together from various provinces to the city of Silchester, and suggested to Dubricius, archbishop of the City of Legions, that he should crown as king Arthur, the late king’s son. For they were in dire need, seeing that when the Saxons heard of Uther’s death they had invited their fellow countrymen from Germany, and under their Duke Colgrin were bent upon exterminating the Britons. They had, moreover, entirely subdued that whole part of the island that stretches from the River Humber to the sea of Caithness. Dubricius therefore, sorrowing over the country’s calamities, assembled the other prelates, and invested Arthur with the crown of the realm. At that time Arthur was a youth of fifteen years, of a courage and generosity beyond compare, and his inborn goodness lent such grace that he was loved by nearly all the peoples in the land. After he had been invested with the royal insignia, he abided by his ancient custom, and was so prodigal with his bounty that he began to run short of largesse to distribute among the huge multitude of knights that flocked to him. But he who has a generous nature along with prowess, though he might be poor for a time, will not remain so forever. Thus Arthur, who combined valor with largesse, resolved to harry the Saxons, so that with their treasure he might enrich his own retainers. In this he was supported by his own lawful right, seeing that by right he ought to hold the sovereignty of the whole island by virtue of his hereditary claim. Assembling all his youthful retainers, he made first for the city of York. And when Duke Colgrin became aware of this, he gathered his Saxons, Scots, and Picts, and came with a mighty multitude to meet Arthur near the River Douglas, where, by the battle’s end, the greater part of both armies had been slain. Nevertheless, Arthur won the day, and after pursuing Colgrin in flight as far as York, besieged him within that city. [Arthur rallies his allies against the Saxons, who are defeated and driven from Britain, as are the Picts and Scots. Arthur rules in peace for twelve years.]

At the end of this time he invited to join him all the bravest men from far-off kingdoms and began to enlarge his household retinue, and to hold such courtly gatherings as led to rivalry among distant peoples, since the noblest in every land, eager to vie with him, would hold himself as nothing unless in the cut of his clothes and the manner of his arms he followed the pattern of Arthur’s knights. At last the fame of his bounty and his prowess was on every man’s tongue, even to the furthest ends of the earth, and a fear fell upon foreign kings lest he might attack them with arms and they might lose the nations under their dominion. Grievously tormented by these devouring cares, these kings set about repairing their cities and the towers of their cities, and built themselves strongholds in places fitting for defense, so that in case Arthur should lead an expedition against them they might find refuge there. [Arthur determines “to subdue all of Europe” and conquers Norway and parts of Gaul, but is recalled to Britain by news of his nephew Mordred’s treason.]