Chapter Four

The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1299

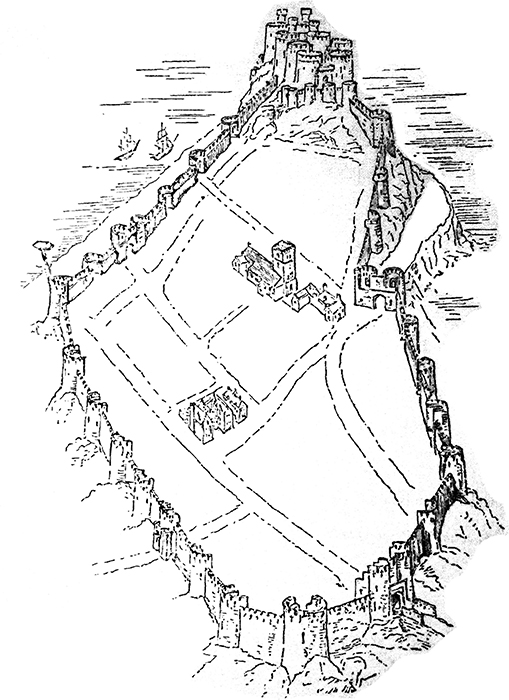

Fig. 32. Conwy Castle and Town. Built in northwest Wales by Edward I (r. 1272–1307) on the site of a monastery favored by the native Welsh princes, the complex at Conwy included a walled town and a formidable curtain-walled castle. The project cost £15,000, a sum equal to over half of the English crown’s annual tax revenues at that time.

51. Letters of Queen Isabella of Angoulême

King John died shortly after issuing Magna Carta, to be succeeded by his nine-year-old son, Henry III (r. 1216–72). The young king’s widowed mother was a southern French noblewoman who had been betrothed to a neighboring Frenchman, Hugh de Lusignan the Elder, before King John managed to marry her instead. She was unpopular at the English royal court and was excluded from her son’s regency government, to her chagrin. At the time she wrote these letters, she had returned to France, where her young daughter Joanna, sister of the little king, was betrothed to Hugh de Lusignan the Younger, son of Isabella’s former fiancé.

Source: trans. A. Crawford, Letters of the Queens of England, 1100–1547 (Dover, NH: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1994), pp. 51–53.

Isabella, Queen of England, to Her Son, Henry III [ca 1218–19]

To her dearest son, Henry, by the grace of God, the illustrious king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, count of Anjou, I Isabella, by the same grace of God, his humble mother, queen of England, always pray for your safety and good fortune.

Your Grace knows how often we have begged you that you should give us help and advice in our affairs, but so far you have done nothing. Therefore we attentively ask you again to dispatch your advice quickly to us, but do not just gratify us with words. You can see that without your help and advice, we cannot rule over or defend our land. And if the truces made with the king of France were to be broken, this part of the country has much to fear. Even if we had nothing to fear from the king himself, we do indeed have such neighbors who are as much to be feared as the said king of France. So without delay you must formulate such a plan which will benefit this part of the country which is yours and ours; it is necessary that you do this to ensure that neither you nor we should lose our land through your failure to give any advice or help. We even beg you to act on our behalf, that we can have for the time being some part of those lands which our husband, your father, bequeathed to us. You know truly how much we owe him, but even if our husband had bequeathed nothing to us, you ought by right to give us aid from your resources, so that we can defend our land, since on this your honor and advantage depend.

Wherefore we are sending over to you Sir Geoffrey de Bodeville and Sir Waleran, entrusting to them many matters which cannot be set down in writing to you, and you can trust them in what they say to you on our behalf concerning the benefit to you and us.

Isabella, Queen of England, to Pandulph, Bishop-Elect of Norwich [ca June 1219]

Dearest father and lord Pandulph, by the grace of God, bishop-elect of Norwich, chamberlain of our lord the pope and legate of the apostolic see, I Isabella, by the same grace, queen of England, lady of Ireland, duchess of Normandy and Aquitaine, and countess of Anjou, greetings.

You will know that we have offered to restore to Bartholomew de Podio, at the entreaty of our son, the king of England, and of his Council, in entirety all his land, his possessions and the rents he received before we came here, with the exception of our castles, and also all his hostages, save for his two sons, whom we desire to hold in fair and fitting custody until we are without fear that he will seek to do us wrong, as he once sought to wrong the count of Augi and the other barons of the land in spite of us. If he refused this offer of ours, we offered him the sure judgment of our court, but he totally rejected all this. We are very surprised that our son’s Council should have instructed Sir Hugh de Lusignan and Sir Geoffrey Neville, seneschal of Poitou, to support the said Bartholomew against us. Granted that the king our son, or his Council, does not order that we be attacked, nevertheless we know many who will trouble us on Bartholomew’s behalf, and our son’s Council should be aware lest it issues any instructions which result in our being driven away from our son’s Council and affairs. It will be very serious if we are removed from our son’s Council. You should know that we have been reliably informed that the aforesaid Bartholomew came into the presence of the king of France and made it known to him that our land was part of his fief; he asked that the king order us to reinstate him in his lands. I certainly think he does not regard our son the king of England very highly, in as much as Bartholomew himself, running hither and thither, is working to harm the king and his people. You should know that Sir Hugh de Lusignan and the seneschal are more eager to carry out this order against us, than they would be if ordered to help us. For if indeed they have been so ordered, until now they have done very little. So we ask you to have orders given, by a letter from the king our son, to Sir Hugh de Lusignan and the seneschal of Poitou to help us and to take counsel for our land and the land of our lord the king. Please write back to us what your will is.

Isabella, Queen of England, Countess of March and Angoulême, to Her Son, Henry III [1220]

To her dearest son, Henry, by the grace of God, king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, count of Anjou, Isabella, by the same grace queen of England, lady of Ireland, duchess of Normandy and Aquitaine, countess of Anjou and Angoulême, sends health and her maternal benediction.

We hereby signify to you that when the counts of March and Eu departed this life, the lord Hugh de Lusignan remained alone and without heirs in Poitou, and his friends would not permit that our daughter should be united to him in marriage, because her age is so tender, but counseled him to take a wife from whom he might speedily hope for an heir; and it was proposed that he should take a wife in France, which if he had done, all your land in Poitou and Gascony would be lost. We, therefore, seeing the great peril that might accrue if that marriage should take place, when our counselors could give us no advice, ourselves married the said Hugh, count of March; and God knows that we did this rather for your benefit than our own. Wherefore we entreat you, as our dear son, that this thing may be pleasing to you, seeing it conduces greatly to the profit of you and yours; and we earnestly pray you that you will restore to him his lawful right, that is, Niort, the castles of Exeter and Rockingham, and 3500 marks, which your father, our former husband, bequeathed to us; and so, if it please you, deal with him, who is so powerful, that he may not remain against you, since he can serve you well—for he is well-disposed to serve you faithfully with all his power; and we are certain and undertake that he shall serve you well if you restore to him his rights, and, therefore, we advise that you take opportune counsel on these matters; and when it shall please you, you may send for our daughter, your sister, by a trusty messenger and your letters patent, and we will send her to you.

Questions: What concerns does Isabella express? How politically active does she seem to have been? What were her goals? What cards did she hold? How do you explain her surprising course of action as described in the final letter? How do these letters compare with those of Eleanor of Aquitaine (doc. 38)?

52. Henry de Bracton’s Notebook: Cases from the Royal Courts

One of the works of Henry de Bracton, a prolific thirteenth-century legal writer, is a collection of summaries of cases from the royal courts. The following cases, all from the year 1230, have been selected to show women as plaintiffs and defendants in civil cases in the royal courts. They can usefully be read in conjunction with the twelfth-century legal treatise by Glanville (doc. 36).

Source: trans. E. Amt from Bracton’s Note-Book, ed. F.W. Maitland (London: C.J. Clay & Sons, 1887), vol. 2, pp. 315–16, 325, 331–32.

382. Muriel, who was the wife of William de Ros, presented herself on the fourth day versus John Marshal concerning a plea to be heard about one third of 60 acres with appurtenances in Wilton, and one third of the pasture of Stanhale, and one third of 16 acres of meadow with appurtenances in the same vill of Wilton, and one third of 4 acres of land and three dwellings with appurtenances in the same vill of Wilton, which thirds she claims versus John Marshal, and she calls to warrant Hugh de Ros, who responds that he is not obliged to warrant that land and meadow to her, because his father William de Ros, by whose gift she claims that land, died and a jury was impaneled previously by assent of the same John and Hugh concerning the 7 virgates [one quarter of a hide, a variable unit] of land with appurtenances in Wilton, to review whether the said William died seised [in possession] of that land or not.

And the jurors said that the same William died seised of the 7 virgates with appurtenances, by which she recovered seisin of one third of the said 7 virgates with appurtenances as her dower. And because no mention was then made in the oath of the said jurors of the aforementioned 60 acres of land nor of the pasture nor of the meadow nor of the 4 acres, and this was omitted by the forgetfulness of the clerks of the bench, provision was made that the said jurors would be re-summoned to certify whether the said William died seised of the aforesaid 60 acres, the meadow, and the pasture, like the 7 virgates of land concerning which they previously swore. The jurors say that the said William died seised of them, just as of the said 7 virgates. And therefore it was decided that Muriel should recover her seisin and John should be in mercy. And be it known that John did not come and had a day at the bench after the jury was re-summoned, and therefore a jury was impaneled for his default, just as in the principal plea. . . .

395. Matilda, abbess of Romsey, was summoned to respond to Roger Wascelin as to how she prevented the same Roger from appointing a suitable clergyman for the church of Stokes, which was vacant, etc., and the right of appointment belongs to the said Roger because the same abbess has granted and handed over to Roger the manor of Stokes with all its appurtenances, except certain things which were specifically excepted in her charter, for a term of seven years.

And the abbess, through Richard the clerk, her attorney by the king’s writ, . . . comes and acknowledges her charter and that she granted the said manor to him to farm for the said term, with all its appurtenances except aids and tallages of men, and except that no one holding land on that manor could marry his daughter outside the fief without first making a fine with the same abbess, and except fines and reliefs of free men, which she withholds for herself with certain other things, no mention being made of the advowson, and [she acknowledges] that the advowson belongs to that manor. And therefore it has been decided that Roger should recover his right of presentation to the same church as tenant, and the abbess is in mercy, and Roger should have a writ of non obstante [a writ defending his right] to the officer of the bishop of Winchester.

403. Alicia, countess of Eu, seeks versus Emma de Belfou 2 carrucates [a plowland, a variable unit] of land with appurtenances in Gunthorpe and in Judham as her right, of which a certain Beatrice her ancestor was seised in her demesne by fee and inheritance, in the time of King Henry [II], grandfather of the lord king, in the year and on the day when he was alive and dead, . . . and the right to that land descended from Beatrice to a certain Henry as son and heir, and from the said Henry to a certain John as son and heir, and from the said John to a certain Henry as son [and heir], and from the said Henry to the same Alicia as daughter and heir. . . .

And Emma comes and defends her right now in all times and places, and she says that she does not have to respond to this writ because at another time the plea about this land was in the lord king’s court, so that a fine was made between Hubert de Burgh, earl of Kent and justiciar of England, plaintiff, and the same Emma, by a chirograph [a handwritten document made in duplicate or triplicate from the same piece of parchment and cut or marked so as to prove its veracity], and that neither she nor anyone on her behalf has made a claim, etc.

And the countess comes and says that this ought not to disadvantage her, because she was then overseas, so that she could not make her claim. And Emma cannot deny this. And therefore it has been decided that she should respond.

And Emma says that she holds this land only for her lifetime, and that this land ought to revert to the said Hubert de Burgh after her death, by the charter made between them, and that this is attested both by the chirograph between them in the lord king’s court and by the charter of the lord king which testifies to this, and she calls the same Hubert de Burgh to warrant this for her.

The same countess through her words and by the same right seeks versus Oliva de Montbegon two carrucates of land with appurtenances in Tuckford as her right [by descent from the same Beatrice.]

And Oliva comes and defends her right now, etc., and she says that she does not have to answer, because the same countess seeks 2 carrucates of land with their appurtenances, and the advowson of the church of the same vill is among the appurtenances, and the same countess makes no exception of the advowson, and therefore she does not want to answer this writ, unless the court so decides.

And the countess says that she claims nothing in that advowson, and she did not put it in her writ, and her ancestors were enfeoffed with 7 carrucates in the same vill without the advowson because those who enfeoffed her ancestors kept that advowson for themselves, and therefore it seems to her that she ought to be answered. Afterward they made an agreement, saving the right of the lord king, if it please the lord king, without whom no agreement can stand. The agreement is that the said Oliva and her heirs will hold the said land with appurtenances from the said countess, etc., for that same service which she previously did for it to the lord king, and both of them will do all in their power to keep the accord.

Questions: What kinds of land tenure are claimed or enforced? What standards of proof are maintained? What is the role of the jury in the first case? How did women use the courts? How do these cases fit with Glanville’s treatise (doc. 36)?

53. Persecution and Expulsion of English Jews

Hostility toward the Jewish minority became more active in the thirteenth century. The following chronicle extracts and royal documents show official and unofficial discrimination against the Jews, culminating in their expulsion from England in 1290. The focus on those Jews who were moneylenders is obvious and clearly contributed to anti-Semitism, but it is important to note that Christians too practiced and profited from usury, even though it was forbidden by canon law.

Sources: ed. A.E. Bland, English Economic History: Select Documents (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1914), pp. 45–47, 50–51; Trokelowe, trans. E.P. Cheney, Readings in English History Drawn from the Original Sources (Boston: Ginn & Company, 1922), pp. 230–31.

Ordinances of Henry III, 1253

The king has provided and decreed . . . that no Jew may dwell in England unless he do the king service, and that as soon as a Jew is born, whether male or female, in some way he shall serve the king. And that there shall be no communities of the Jews in England except in those places where such communities were in the time of the lord king John, the king’s father. And that in their synagogues the Jews, one and all, shall worship in subdued tones according to their rite, so that Christians hear it not. And that all Jews shall answer to the rector of the parish in which they dwell for all parochial duties belonging to their houses. And that no Christian nurse shall hereafter suckle or nourish the male child of any Jew, and that no Christian man or woman shall serve any Jew or Jewess, nor eat with them, nor dwell in their house. And that no Jew or Jewess shall eat or buy meat in Lent. And that no Jew shall disparage the Christian faith, nor publicly dispute touching the same. And that no Jew shall have secret intercourse with any Christian woman, nor any Christian man with a Jewess. And that every Jew shall wear on his breast a conspicuous badge. And that no Jew shall enter any church or any chapel save in passing through, nor stay therein to the dishonor of Christ. And that no Jew shall in any way hinder another Jew who is willing to be converted to the Christian faith. And that no Jew shall be received in any town without the special license of the king, except in those towns where Jews have been accustomed to dwell.

Threatened Expulsion of Salle of Canterbury, 1253

The king, etc., to the sheriff of Kent, etc. Know that we caused to be assessed before us upon Salle [Solomon], a Jew, a tallage to be rendered on Wednesday next before Whitsunday in the thirty-seventh year of our reign, and because the same Jew did not render his tallage on the same day he received a command on our behalf before the justices [appointed to the guardianship of the Jews] that within three days after the aforesaid Wednesday he should make his way to the port of Dover to go forth with his wife and never to return, forfeiting his lands to the king. We command you that by oath of twelve good and lawful men you make diligent enquiry what lands he had on the same day, and who holds them, and how much they are worth . . . and that you enquire also by oath, what chattels he had in all chirographs outside the chest, and what they are worth, and to whose hands they have come, and that you have it proclaimed that none of Salle’s debtors shall hereafter render a penny to him—let the proclamation be made in every hundred, city, etc.—and that you take into our hand all the lands, rents and tenements and chattels aforesaid, and safely. . . . [Salle avoided deportation by paying the tallage, and the following year successfully petitioned Henry III to lower his tallage.]

John of Trokelowe’s Chronicle

At this time [in 1290] there were Jews dwelling among the Christians in every city and famous town in England. King Edward [I], with the advice of his nobles, ordered them to leave the country, and to depart without fail on one day, and this was the decree: that whatever Jew should be found in England after the first warning should either be plunged in the baptismal font and thus faithfully acknowledge Christ, the son of God, or should have his head cut off. Immediately the Jews, struck with the fear of death, left England, carrying all their possessions with them. When their vessels had set sail and been carried out to sea, storms arose, severe winds blew, their ships were shattered, and many were drowned. Certain ones driven upon the shores of France, by the judgment of God, perished miserably. At length the king of France was touched with pity, although these were enemies of God, and since they were God’s creatures, although ungrateful ones, he permitted them to dwell in his kingdom for a short time, and to settle in Amiens. When this was reported in Rome, and reached the ears of the pope, he burned with rage and bitterly denounced the king.

Edward I’s Order, 1290

Edward . . . to the treasurer and barons of the exchequer, greeting. Whereas formerly in our Parliament at Westminster on the quinzaine of Saint Michael in the third year of our reign, to the honor of God and the profit of the people of our realm, we ordained and decreed that no Jew thenceforth should lend anything at usury to any Christian on lands, rents or other things, but that they should live by their commerce and labor; and the same Jews, afterward maliciously deliberating among themselves, contriving a worse sort of usury called “courtesy,” have depressed our people aforesaid on all sides under the color thereof, the last offense doubling the first; whereby, for their crimes and to the honor of the crucified [Christ], we have caused those Jews to go forth from our realm as traitors: We, wishing to swerve not from our former choice, but rather to follow it, do make totally null and void all manner of penalties and usuries and every sort thereof, which could be demanded by actions by reason of the Jewry from any Christians of our realm for any times whatsoever; wishing that nothing be in any wise demanded from the Christians aforesaid by reason of the debts aforesaid, save only the principal sums which they received from the Jews aforesaid; the amount of which debts we will that the Christians aforesaid verify before you by the oath of three good and lawful men by whom the truth of the matter may be better known, and thereafter pay the same to us at terms convenient to them to be fixed by you. And therefore we command you that you cause our grace so piously granted to be read in the aforesaid exchequer, and to be enrolled on the rolls of the same exchequer, and to be carefully guarded, according to the form above noted. . . .

Questions: What seem to be Christian concerns about Jews? What evidence is there of a shift in English attitudes toward Jews over time? Are there any hints of sympathy for the Jews, any softening of older defamations, slanders, and crude caricatures (as seen in docs. 42, 50)?

54. The Ancrene Wisse

The monastic life was not the only way to dedicate oneself to religion; many men and even more women became anchorites and anchoresses, or hermits. While early Christian hermits had usually dwelt in near total isolation and very harsh conditions, the hermits of medieval England lived rather different lives. The following excerpts come from a set of guidelines produced for a small group of anchoresses, sometime in the first half of the thirteenth century.

Source: trans. J. Morton, The Nun’s Rule, Being the Ancren Riwle Modernised (London: De La More Press, 1905), pp. 164–65, 237–39, 278–79, 312–20; revised.

2. Of Temptations

. . . An anchoress thinks that she shall be most strongly tempted in the first twelve months after she shall have begun her monastic life, and in the twelve thereafter; and when, after many years, she feels them so strong, she is greatly amazed, and is afraid lest God may have quite forgotten her, and cast her off. No, it is not so! In the first years, it is nothing but ball-play; but now, observe well, by a comparison, how it fares. When a man has brought home a new wife, he, with great gentleness, observes her manners. Though he sees in her some thing that he does not approve, yet he takes no notice of it, and puts on a cheerful countenance toward her, and carefully uses every means to make her love him, affectionately in her heart; and when he is well assured that her love is truly fixed upon him, he may then, with safety, openly correct her faults, which he previously bore with as if he knew them not: he becomes very stern, and assumes a severe countenance, in order still to test whether her love toward him might give way. At last when he perceives that she has been completely instructed—that for nothing that he does to her does she love him less, but more and more, if possible, from day to day, then he shows her that he loves her sweetly, and does whatever she desires, as for one whom he loves and knows—then all that sorrow becomes joy. If Jesus Christ, your spouse, acts thus to you, my dear sisters, it should not seem strange to you. For in the beginning it is only courtship, to draw you into love; but as soon as he perceives that he is on a footing of affectionate familiarity with you, he will have less forbearance with you; but after the trial—in the end—then is the great joy. . . .

3. Confession shall be complete, that is, all said to one man, from childhood. When the poor widow would clean her house, she gathers into a heap, first of all, all the largest sweepings, and then shovels it out; after this, she comes again and heaps together all that was left before, and shovels it out also; again, upon the small dust, if it is very dusty, she sprinkles water, and sweeps it quite away after all the rest. In like manner must he that confesses himself, after the great sins, shovel out the small, and if the dust of light thoughts fly up too much, sprinkle tears on them, so they will not blind the eyes of the heart. Whoever hides anything has told nothing. . . . We are told of a holy man who lay on his deathbed, and was unwilling to confess a particular sin from his childhood, and his abbot urged him by all means to confess it. He answered and said that it was not necessary, because he was only a child when he did it. Reluctantly, however, at last, through the searching exhortations of the abbot, he told it, and died soon thereafter. After his death, he came one night and appeared to his abbot in snow-white garments, as one who was saved, and said that if he had not fully confessed that particular thing which he did in childhood, he should certainly have been condemned among those who are lost. . . .

4. Confession must also be candid, that is, made without any concealment, and not palliated by comparisons, nor gently touched upon. But the words should be spoken plainly according to the deeds. It is a sign of hatred when men reprehend severely a thing that is greatly hated. If you hate your sin, why do you speak of it in gentle terms? Why do you hide its foulness? Speak out its shame reproachfully, and rebuke it very sharply, if you would indeed confound the devil. “Sir,” says the woman, “I have had a lover,” or, “I have been foolish.” This is not plain confession. Put no cloak over it. Take away the accessories, that is, the circumstances. Uncover yourself and say, “Sir, I beg the mercy of God, and thine! I am a foul stud mare: a stinking whore.” Give your enemy a foul name, and call your sin by its name without disguise, that is, conceal nothing at all that is connected with it. Yet what is too foul may not be spoken. The foul deed need not be named by its own foul name. It is sufficient to speak of it in such a manner that the father confessor may clearly understand what you mean. . . .

6. Of Penance

. . . Let not anyone handle herself too gently, lest she deceive herself. She will not be able, for her life, to keep herself pure, nor to maintain her chastity without two things, as Saint Aelred [of Rievaulx] wrote to his sister. The first thing is giving pain to the flesh by fasting, by watching, by flagellations, by wearing coarse garments, by a hard bed, with sickness, and with much labor. The second thing is the moral qualities of the heart, such as devotion, compassion, mercy, pity, charity, humility, and other virtues of this kind. “Sir,” you answer me, “does God sell his grace? Is not grace a free gift?” My dear sisters, although purity is not bought from God, but is given freely, ingratitude resists it, and renders those who will not cheerfully submit to labor for it unworthy to possess so excellent a thing. Who was ever chaste amidst pleasures and ease, and carnal abundance? Who ever carried fire within her that did not burn? Shall not a pot that boils rapidly be emptied of some of the water, or have cold water cast into it, and the burning fuel withdrawn? The pot of the belly that is always boiling with food, and especially with drink, is such a near neighbor to that ill-disciplined member that it imparts to it the fire of its heat. Yet many anchoresses, more is the harm, are of such fleshly wisdom, and so exceedingly afraid lest their head ache, and lest their body be too enfeebled, and are so careful of their health, that the spirit is weakened and sickens in sin, and they who ought alone to heal their soul with contrition of heart and mortification of the flesh, become physicians and healers of the body. Did Saint Agatha do so? She who answered and said to our Lord’s messenger who brought her salve to heal her breasts, “Fleshly medicine I never applied to myself.” . . . Wisdom is the mother and the nurse of all virtues; but we often call that wisdom which is not wisdom. For it is true wisdom to prefer the health of the soul to that of the body, and, when we cannot have them both, to choose bodily hurt rather than, by too powerful temptations, the destruction of the soul. . . .

8. Of Domestic Matters

I said at the outset that you should not, like unwise people, promise to keep any of the external rules. I say the same still; nor do I write them down for any but you alone. I say this in order that other anchoresses may not say that I, by my own authority, am making new rules for them. Nor do I command that they observe them, and you may even change them, whenever you wish, for better ones. In regard to things of this kind that have been in use before, it matters little.

Enough has been said about sight, and of speech, and of the other senses. Now this last part, as I promised you at the commencement, is divided and separated into seven small sections.

Men esteem a thing to be less precious when they have it often, and therefore you should be, as lay brethren are, partakers of the holy communion only fifteen times a year: at midwinter [25 December]; Candlemas [2 February]; Twelfth-day [6 January]; on Sunday halfway between that and Easter, or our Lady’s day [25 March], if it is near the Sunday, because of its being a holiday; Easter day; the third Sunday thereafter; Holy Thursday [Ascension Day, forty days after Easter]; Whitsunday [Pentecost, six weeks after Easter]; and midsummer day [24 June]; Saint Mary Magdalen’s day [22 July]; the Assumption [15 August]; the Nativity [of the Virgin Mary, 8 September]; Saint Michael’s day [29 September]; All Saints’ day [1 November]; Saint Andrew’s day [30 November]. And before all these days, see that you make a full confession and undergo discipline; but never from any man, only from yourselves. And forego your pittance for one day. And if any thing happens out of the usual order, so that you cannot receive the sacrament at these set times, you may make up for it on the next Sunday, or if the other set time is near, you may wait till then.

You shall eat twice every day from Easter until the later Holyrood day [14 September], which is during harvest time, except on Fridays, and ember days [days of fasting and prayer in each season of the year], and procession days and vigils. In those days, and in the Advent, you shall not eat anything white, except when necessity requires it. The other half year you shall fast always, except on Sundays.

You shall eat no flesh nor lard except if you are gravely ill, and whoever is infirm may eat potage without scruple, and accustom yourselves to little drink. Nevertheless, dear sisters, your meat and your drink have seemed to me less than I would have it. Fast no day upon bread and water, unless you have permission. There are anchoresses who make their meals with their friends outside the convent. That is too much friendship, because, of all orders, this is most contrary to the order of an anchoress, who is quite dead to the world. . . . Make no banquetings, nor encourage any strange vagabond fellows to come to the gate; though no other evil may come of it but their immoderate talking, it might sometimes prevent heavenly thoughts.

It is not fit that an anchoress should be liberal with other men’s alms. Would we not laugh out loud to scorn a beggar who should invite men to a feast? Mary and Martha were two sisters, but their lives were different. You anchorites have taken to yourselves Mary’s part, whom our Lord himself commended. . . . Housewifery is Martha’s part, and Mary’s part is quietness and rest from all the world’s din, that nothing may hinder her from hearing the voice of God. And observe what God says, “that nothing shall take away this part from you.” Martha has her office; leave her alone, and sit with Mary stone-still at God’s feet, and listen to him alone. Martha’s office is to feed and clothe poor men, as befits the mistress of a house. Mary ought not to intermeddle in it, and if anyone blames her, God himself defends her for it, as holy writ bears witness. On the other hand, an anchoress ought to take sparingly only that which is necessary for her. How, then, can she be generous? She must live upon alms as frugally as she can, and not gather that she may give it away afterward. She is not a housewife. . . .

You shall not possess any beast, my dear sisters, except a cat. An anchoress that has cattle appears as Martha was, a better housewife than anchoress; nor can she in any wise be Mary, with peacefulness of heart. For then she must think of the cow’s fodder, and of the herdsman’s hire, flatter the hayward, defend herself when her cattle are shut up in the pinfold, and moreover pay the damage. . . . An anchoress ought not to have anything that draws her heart outward. Carry on no business. An anchoress that is a buyer and seller sells her soul to the chapman of hell. Do not take charge of other men’s property in your house, nor of their cattle, nor their clothes, neither receive under your care the church vestments, nor the chalice, unless force or great fear compels you, for much harm has often come from such caretaking. Let no man sleep within your walls. If, however, great necessity should cause your house to be used, see that, as long as it is used, you have inside there with you a woman of blameless life day and night.

Because no man sees you, nor do you see any man, you may be well content with your clothes, be they white, be they black; only see that they be plain, and warm, and well made, of skins well tawed; and have as many as you need, for your bed as well as for your back.

Next to your flesh you shall wear no flaxen cloth, unless it be of hard and coarse canvas. . . . You shall sleep in a garment and with a belt. Wear no iron, nor haircloth, nor hedgehog-skins; and do not beat yourselves with a scourge of leather thongs, nor a leaded one; and do not cause yourselves to bleed with holly nor with briars without leave of your confessor; and do not use too many flagellations at any time. Let your shoes be thick and warm. . . . Have neither ring, nor brooch, nor ornamented girdle, nor gloves, nor any such thing that is not proper for you to have. . . .

You shall not send, nor receive, nor write letters without leave. You shall have your hair cut four times a year to unburden your head, and be bled as often, and oftener if it is necessary; but if anyone can dispense with this, I will permit it. When you are bled, do nothing that may be irksome to you for three days, but talk with your maidens, and divert yourselves together with instructive tales. You may often do so when you feel dispirited, or are grieved about some worldly matter, or sick. Thus wisely take care of yourselves when you are bled, and keep yourselves in such rest that long thereafter you may labor the more vigorously in God’s service, and also when you feel any sickness, for it is great folly, for the sake of one day, to lose ten or twelve. Wash yourselves wheresoever it is necessary, as often as you please.

When an anchoress does not have her food at hand, let two women be employed, one who stays always at home, another who goes out when necessary; and let her be very plain, or of sufficient age. . . . Let neither of the women either carry to her mistress or bring from her any idle tales, or new tidings, nor sing to one another, nor speak any worldly speeches, nor laugh, nor play, so that any man who saw it might turn it to evil. . . . No servant of an anchoress ought, properly, to ask stated wages, except food and clothing, with which, and with God’s mercy, she may do well enough. . . . Whoever has any hope of so high a reward will gladly serve, and easily endure all grief and all pain. With ease and abundance men do not arrive at heaven. . . .

Questions: How hermit-like were anchoresses? Which aspects of the Ancrene Wisse would be relevant to ordinary laypeople? Which are specific to female anchoresses? What was the appeal of such a life? Why might it appeal more to women than to men?

55. Thomas of Eccleston on the Coming of the Friars Minor to England

The religious ferment of the High Middle Ages gave rise to many new religious orders, including the mendicant or “begging” orders, the Dominicans and Franciscans, in the early thirteenth century. In the extracts below, the Franciscan brother Thomas, later called “of Eccleston,” tells of the arrival of the Franciscans in England in 1224.

Source: trans. H. Rothwell, English Historical Documents, Vol. 3: 1189–1327 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), pp. 680–83.

Of the First Coming of the Friars Minor to England

In A.D. 1224, in the time of the lord pope Honorius [III], in the same year, that is, in which he confirmed the Rule of the blessed Francis, the eighth year of the reign of the lord king Henry [III], son of John, on [10 September,] the Tuesday after the feast of the nativity of the Blessed Virgin, which in that year fell on a Sunday, the friars minor first arrived in England at Dover, being four clerks and five laymen.

The clerks were these: first, Brother Agnellus of Pisa, in orders a deacon, in age about thirty, who had at the last general chapter been designated by the blessed Francis [of Assisi] as minister provincial for England: he had been custodian at Paris and had borne himself so discreetly as to win the highest favor among the brethren and lay folk alike by reason of his renowned holiness.

The second was Brother Richard of Ingworth, an Englishman by birth, a priest and preacher, and an older man. He was the first of the order to preach to people north of the Alps. In course of time, under Brother John Parenti of happy memory, he was sent to Ireland to be minister provincial; he had been Brother Agnellus’s vicar in England while Agnellus himself went to the general chapter in which the translation was effected of the remains of Saint Francis and had set a notable example of exceeding holiness. When he had fulfilled a ministry faithful and well pleasing to God, he was absolved in the general chapter by Brother Albert of happy memory from holding any further offices among the brethren, and, fired by zeal for the faith, set out for Syria [on pilgrimage] and there, making a good death, fell on sleep.

The third was Brother Richard of Devon, also an Englishman by birth, in orders an acolyte, in age a youth; he left us many examples of long-suffering and obedience. For after he had traveled through diverse provinces under obedience, he lived, though frequently worn out by quartan fevers, for eleven whole years at the place [a small Franciscan house] at Romney.

The fourth was Brother William of Ashby, still a novice wearing the hood of a probationer, likewise English by birth, young in years and in standing. For a long time he endured various offices in praiseworthy fashion, the spirit of Jesus Christ aiding him, and he showed us examples of humility and poverty, love and gentleness, obedience and patience and every perfection. For when Brother Gregory, minister in France, asked him if he willed to go to England, he replied that he did not know. And when the minister marveled at this reply, Brother William at length said the reason he did not know what he wished was that his will was not his own but the minister’s. For this reason he willed whatsoever the minister willed him to will. Brother William of Nottingham testified of him that he was perfect in obedience, for when he offered him the choice of the place where he would live, he said that that place best pleased him which it pleased the brother to appoint for him. And because he was specially gifted with charm and a most prepossessing gentleness, he called forth the goodwill of many layfolk toward the order. Moreover, he brought into the way of salvation many persons of diverse positions, ages and ranks, and in many ways he gave convincing proof that sweet Jesus knew how to do marvelous things. . . . At a time of fleshly temptation he mutilated himself in his zeal for chastity. After which he sought the pope, who, though severely reproving him, granted him a dispensation so that he might celebrate the divine offices. After many years this same William died peacefully in London. . . .

These nine [members of the Franciscan mission] were out of charity conveyed across to England and courteously provided for in their need by the monks of Fécamp. When they reached Canterbury, they stayed for two days at the priory of the Holy Trinity, then without delay four of them set off to London, namely Brother Richard of Ingworth, Brother Richard of Devon, Brother Henry and Brother Melioratus. The other five went to the priests’ hospital, where they remained until they had found somewhere to live. In fact, a small room was soon afterward granted them underneath the schoolhouse, where they sat all day as if they were enclosed. But when the scholars returned home in the evening they went into the schoolhouse in which they had sat and there made themselves a fire and sat beside it. And sometimes they set on the fire a little pot containing dregs of beer when it was time to drink at the evening collation, and they put a dish in the pot and drank in turn, and one by one they spoke some edifying words. And one who was their associate in this unfeigned simplicity and holy poverty, and merited to be a partaker in it, bore witness that their drink was sometimes so thick that when it had to be heated they put water in and so drank it joyfully. . . .

Of the First Separation of the Brethren

Now when they reached London, the four brethren already named went to the Friars Preachers [the Dominicans], and were graciously received by them. They remained with them for fifteen days, eating and drinking what was set before them quite as if they were members of the house. After this, they rented a house for themselves in Cornhill and made cells for themselves in it, stuffing grasses into gaps in the cells. And they remained in that simple state until the following summer, with no chapel, for they had not yet been granted the privilege of setting up altars and celebrating the divine offices in their own places.

And without delay, before the feast of All Saints [1 November], and even before Brother Agnellus came to London, Brother Richard of Ingworth and Brother Richard of Devon set out for Oxford and there were similarly received in the friendliest manner by the Friars Preachers; they ate in their refectory and slept in their dormitory like members of their house for eight days. After that they rented a house for themselves in the parish of St. Ebbe’s, and there remained without a chapel until the following summer. There sweet Jesus sowed a grain of mustard-seed that afterward became greater than all herbs. From there Brother Richard of Ingworth and Brother Richard of Devon set out for Northampton and were taken in at the hospital there. Afterward they rented a house for themselves in the parish of St. Giles, where the first guardian was Brother Peter the Spaniard, he who wore an iron corselet next to his skin and gave many other examples of perfection. . . .

Sir John Travers first received the brethren in Cornhill and rented a house for them, and a certain Lombard, a layman, Henry by name, was made its guardian. He then for the first time learned to read, by night, in the church of Saint Peter, Cornhill. Afterward he was made vicar of the English province while Brother Agnellus was going to the general chapter. In the vicariate he had, however, as coadjutor Brother Richard of Ingworth. But he did not support such a high state of happiness unto the end, rather growing luxurious in these honors and estranged from his true self, and he apostatized from the order in pitiable fashion.

It is worthy of record that in the second year of the administration of Brother Peter, the fifth minister in England, in the thirty-second year, to wit, from the coming of the brethren to England, the brethren living in England in forty-nine places were numbered at twelve hundred and forty-two.

Questions: How was the Franciscan mission organized? What role does divine intervention play in Thomas’s story? What do we learn about the organization of the order in general? What characteristics of the Franciscan brothers were most highly prized? What signs are there of the absolute poverty promoted by the order?

56. The Baronial Cause: The Song of Lewes

Despite his early reaffirmation of Magna Carta, King Henry III (r. 1216–72) found his reign plagued by clashes with his barons, which eventually ended in civil war. The main issue was the barons’ insistence that the king should be guided by their advice rather than that of his “foreign favorites”—a problem foreshadowed in Magna Carta. Earl Simon de Montfort, formerly a close friend of the king, emerged as the leader of the rebellious barons in the 1260s and led them to an important victory over the king at the Battle of Lewes in 1264. A number of political songs supporting the baronial cause survive from this era; the excerpts below come from one such song, written shortly after the battle.

Source: trans. T. Wright, The Political Songs of England, from the Reign of John to That of Edward II (London: The Camden Society, 1839), pp. 72–73, 75–77, 96–101, 102, 103–6, 108–9, 110–11, 112–14, 114–17, 117–18, 120–21; revised.

Write quickly, O pen of mine, for, writing such things as follow, I bless and praise with my tongue thee, O right hand of God the Father, Lord of virtues, who gives prosperity at thy nod to thine own, whenever it is thy will. Let all those people now learn to put their trust in thee, whom they, who are now scattered, wished to destroy—they of whom the head is now taken, and the members are in captivity; the proud people is fallen; the faithful are filled with joy. Now England breathes in the hope of liberty; may the grace of God grant this land prosperity! The English were despised like dogs; but now they have raised their head over their vanquished enemies.

In the year of grace 1264, and on [14 May,] the Wednesday after the festival of Saint Pancras, the army of the English bore the brunt of a great battle at the castle of Lewes: for reasoning yielded to rage, and life to the sword. They met on the fourteenth of May, and began the battle of this terrible strife; which was fought in the county of Sussex, and in the bishopric of Chichester. The sword was powerful; many fell; truth prevailed; and the false men fled. For the Lord of valor resisted the perjured men, and defended those who were pure with the shield of truth. . . .

May the Lord bless Simon de Montfort! and also his sons and his army! who, exposing themselves magnanimously to death, fought valiantly, condoling the lamentable lot of the English who, trodden under foot in a manner scarcely to be described, and almost deprived of all their liberties, nay, of their lives, had languished under hard rulers, like the people of Israel under Pharaoh, groaning under a tyrannical devastation. . . . They call Simon a seducer and a traitor, but his deeds prove him to be a true man. Traitors fall off in time of need; they who do not fly from death are those who stand for the truth. . . .

The earl [Simon] had few men used to arms; the royal party was numerous, having assembled the disciplined and greatest warriors in England, such as were called the flower of the army of the kingdom; those who were prepared with arms from among the Londoners were three hundred set before several thousand, so they were contemptible to those, and were detested by those who were experienced. Much of the earl’s army was raw; fresh in arms, they knew little of war. The tender youth, only now girded with a sword, stands in the morning in battle accustoming himself to arms; what wonder if such an unpracticed tyro [a beginner] would fear, and if the powerless lamb dread the wolf? Thus those who fight for England are inferior in military discipline, and they are much fewer than the strong men who boasted in their own valor, because they thought they would safely, and without danger, swallow up, as it were, all of the earl’s helpers. Moreover, of those whom the earl had brought to the battle, and from whom he hoped for no little help, many soon withdrew from fear, and took flight as though they were amazed; and of three parts, one deserted. But the earl with a few faithful men never yielded. . . .

Lo! we are touching the root of the perturbation of the kingdom of which we are speaking, and of the dissension of the parties who fought the said battle. The objects at which these two parties aimed were different. The king, with his [supporters], wished thus to be free: . . . and they said he would cease to be king, deprived of the rights of a king, unless he could do whatever he pleased; they said it was no part of the duty of the magnates of the kingdom to determine whom he should prefer to his earldoms, or on whom he should confer the custody of castles, or whom he would have to administer justice to the people, and to be chancellor and treasurer of the kingdom. He wanted to have everyone at his own will, and counsellors from whatever nation he chose, and all ministers at his own discretion; while the barons of England were not to interfere with the king’s actions, the command of the prince having the force of law, and what he may dictate binding upon everybody at his pleasure. For [they argued that] every earl also is thus his own master, giving to every one of his own men both as much as he will, and to whom he will; he commits castles, lands, revenues, to whom he will; and although he be a subject, the king permits it all. Which, if he do well, is profitable to the doer; if not, he must himself see to it; the king will not hinder him from injuring himself. Why is the prince worse in condition, [they asked,] when the affairs of the baron, the knight, and the freeman, are thus managed? Therefore, [the king’s supporters argued,] they who wish to diminish the king’s power aim at making the king a slave, taking away his princely dignity; they wish by sedition to make the royal power captive and reduce it into guardianship and subjection, and to disinherit the king, making him unable to reign as fully as the kings who preceded him have done, who were in no way subjected to their people, but administered their own affairs at will, and conferred what they had to confer according to their own pleasure. This is the king’s argument, which has an appearance of fairness, and this is alleged in defense of the right of the kingdom.

But now let my pen turn to the other side: let me describe the object at which the barons aim; and when both sides have been heard, let the arguments be compared, and then let us come to a final judgment, so that it may be clear which side is the truest. The people are more prone to obey the truer party. Let therefore the party of the barons speak for itself, and proclaim in order by what zeal it is led. In the first place, this party protests openly that it has no designs against the kingly honor; no, it seeks the contrary, and tries to reform and magnify the kingly condition, just as if the kingdom were ravaged by enemies, for then it would not be reformed without the barons, who would be the most capable and proper persons for this purpose; and should anyone then hang back, the law would punish him as a perjurer and traitor to the king, who owes to his lord, when he is in danger, all the aid he can give to support the king’s honor, when the kingdom is, as it were, near its end by devastation.

The adversaries of the king are enemies who make war upon him, and counsellors who flatter the king, who seduce their prince with deceitful words, and who lead him into error by their double tongues: these are adversaries worse than those who are obstinate; it is these who pretend to be good while they are seducers, and procurers of their own advancement; they deceive the incautious, whom they render less vigilant by means of things that please them, whereby they are not provided against, but are considered as prudent advisers. Such men can deceive more than those who act openly, as they are able to make an outward appearance of being not hostile. What if such wretches, and such liars, should haunt the prince, capable of all malice, of fraud, of falsehood, excited by the spurs of envy, and should seek to do that extreme wickedness, by which they should sacrifice the privileges of the kingdom to their own ostentation, and they should contrive all kinds of hard reasons, which by degrees should confound the commonalty, should bruise and impoverish the mass of the people, and should subvert and infatuate the kingdom, so that no one could obtain justice, except he who would encourage the pride of such men as these by large supplies of money? Who could submit to the establishment of such an injury? And if such men, by their conduct, should change the state of the kingdom; if they should banish justice to put injustice in its place; if they should call in strangers and trample upon the natives; and if they should subdue the kingdom to foreigners; if they should not care for the magnates and nobles of the land, and should place contemptible persons over them; and if they should overthrow and humiliate the great; if they should pervert and turn upside down the order of things; if they should leave the measures that are best, to advance those which are worst—do not those who act thus devastate the kingdom? Although they do not make war upon it with foreign arms, yet they fight with diabolical arms, and they violate the constitution of the kingdom in a lamentable manner. . . .

Thus, in order that none of the aforesaid things may happen, which may hinder peace and good customs, but that the zeal of the experienced men may find what is most expedient for the utility of the many, why is a reform not permitted, with which no corruption shall be mixed? For the king’s mercy and the king’s majesty ought to approve the endeavors which amend grievous laws so that they may be milder, and become less onerous to men but more pleasing to God. . . .

Since it is clear that the barons have a right to do all this, it remains to answer the king’s arguments. The king wishes to be free by the removal of his guardians, and he wishes not to be subject to his inferiors, but to be placed over them; he wishes to command his subjects and not be commanded; he wishes to be humiliated neither to himself nor to those who are his officers. For the officers are not set over the king; on the contrary, they are rather the noble men who support the law. Otherwise there would not be one king of one state, but they to whom the king was subject would reign equally. Yet this inconvenience also, though it seems so great, is easily solved with the assistance of God: for we believe that God wills truth, and it is through him that we dissolve this doubt as follows. He by whom the universe is ruled in pure majesty is said to be, and is in truth, one king alone, who wants neither help whereby he may reign, nor even counsel, in as much as he cannot err. Therefore, all-powerful and all-knowing, he excels in infinite glory all those whom he has appointed to rule and, as it were, to reign under him over his people, who may fail, and who may err, and who cannot avail by their own independent strength, and vanquish their enemies by their own valor, nor govern kingdoms by their own wisdom, but in an evil manner wander in the track of error. They require help and counsel which should set them right. The king says, “I agree to your reasoning; but the choice of these must be left to my option; I will associate with myself whom I will, by whose support I will govern all things; and if my ministers should be insufficient, if they lack sense or power, or if they harbor evil designs, or are not faithful, but are perhaps traitors, I desire that you will explain, why I ought to be confined to certain persons, when I might succeed in obtaining better assistance?” The reason of this is quickly declared, if it be considered what the constraint on the king is: constraint does not necessarily deprive of liberty, nor does every restriction take away power. Princes desire free power; those who reign decline miserable servitude. To what will a free law bind kings?—to prevent them from being stained by an adulterated law. And this constraint is not one of slavery, but is rather an enlargement of the kingly faculty. . . .

It is hard to love one who does not love us; it is hard not to despise one who despises us; it is hard not to resist one who ruins us; we naturally applaud him who favors us. It is not the part of a prince to bruise, but to protect; neither is it the part of a prince to oppress, but rather to deserve the favor of his people by numerous benefits conferred upon them, as Christ by his grace has deserved the love of all. If a prince love his subjects, he will necessarily be repaid with love; if he reign justly, he will of necessity be honored; if the prince err, he ought to be recalled by those whom his unjust denial may have grieved, unless he be willing to be corrected; if he is willing to make amends, he ought to be both raised up and aided by these same persons. Let a prince maintain such a rule of reigning, that it may never be necessary for him to avoid depending on his own people. The ignorant princes who confound their subjects will find that those who are unconquered will not thus be tamed. If a prince thinks that he alone has more truth, more knowledge, and more intelligence than the whole people, that he abounds more in grace and the gifts of God, if it be not presumption, but it be truly so, then his instruction will visit the true hearts of his subjects with light, and will instruct his people with moderation. . . .

Therefore, let the community of the kingdom advise; and let it be known what the generality thinks to whom their own laws are best known. Nor are all those of the country so uninstructed, as not to know better than strangers the customs of their own kingdom, which have been bequeathed from father to son. They who are ruled by the laws know those laws best; they who experience them are best acquainted with them; and since it is their own affairs which are at stake, they will take more care, and will act with an eye to their own peace. They who want experience can know little; they who are not steadfast will profit the kingdom little. Hence it may be concluded that it concerns the community to see what sort of men ought justly to be chosen for the utility of the kingdom; they who are willing and know how, and are able to profit it, such men should be made the councilors and coadjutors of the king, to whom are known the various customs of their country, who feel that they suffer themselves when the kingdom suffers; and who will guard the kingdom, lest, if hurt be done to the whole, the parts have reason to grieve while they suffer along with it; who rejoice, when it has cause to rejoice, if they love it. . . . Therefore, let a prince seek such [councilors] as may condole with the community, who have a motherly fear lest the kingdom should suffer. But if anyone be not moved by the ruin of the many . . . he is not fit to rule over the many, since he is entirely devoted to his own interest, and to none other. A man who feels for others is agreeable to the community; but a man who does not feel for others, who possesses a hard heart, cares not if misfortunes fall upon the many—such walls are no defense against misfortunes. Therefore, if the king lacks the wisdom to choose by himself those who are capable of advising him, it is clear, from what has been said, what ought to be done. For it is a thing which concerns the community to see that miserable wretches not be made the leaders of the royal dignity, but the best and chosen men, and the most approved that can be found. For since the governance of the kingdom is either the safety or perdition of all, it is of great consequence who they are that have the custody of the kingdom, just as it is in a ship: all things are thrown into confusion if unskilled people guide it; if any one of the passengers belonging to it who is placed in the ship abuse the rudder, it matters not whether the ship be governed prosperously or not. So those who ought to rule the kingdom, let the care be given to them, if any one of the kingdom does not govern himself rightly; he goes on a wrong path which perhaps he has himself chosen. The affairs of the generality are best managed if the kingdom is directed in the way of truth. And, moreover, if the subjects labor to dissipate their property, those who are set over them may restrain their folly and temerity, lest by the presumption and imbecility of fools, the power of the kingdom be weakened, and courage be given to enemies against the kingdom. For whatever member of the body be destroyed, the strength of the body is diminished thereby. So if it be allowed even that men may abuse what belongs to themselves, when it be injurious to the kingdom, many others, immediately repeating the injurious liberty, will so multiply the wildness of error, that they will ruin the whole. Nor ought it properly to be named liberty, which permits fools to govern unwisely; but liberty is limited by the bounds of the law, and when those bounds are despised, it should be known as error. . . . Therefore the king’s argument concerning his subjects, who are ruled at their own choice by whom they will, is by this sufficiently answered and overthrown; since every one who is subject is ruled by one who is greater. For we say that no man is permitted to do all that he wishes, but that everyone has a lord who may correct him when he errs, and aid him when he does well, and who sometimes lifts him up when he falls. We give the first place to the community: we say also that the law rules over the king’s dignity; for we believe that the law is the light, without which we conclude that he who rules will wander from the right path. . . . If the king lacks this law, he will wander from the right track; if he does not hold it, he will err foully; its presence gives the power of reigning rightly, and its absence overturns the kingdom. . . . It is commonly said, “As the king wills, so goes the law,” but the truth is otherwise, for the law stands, but the king falls. Truth and charity and the zeal of salvation, this is the integrity of the law, the regimen of virtue: truth, light, charity, warmth, zeal. . . . Whatever the king may ordain, let it be consonant with these; for if it be otherwise, the commonalty will be made sorrowful; the people will be confounded, if either the king’s eye lacks truth, or the prince’s heart lacks charity, or he does not always moderately fulfill his zeal with severity.

These three things being supposed, whatever pleases the king may be done; but by their opposites the king resists the law. However, kicking against it does not hurt the spur; thus the instruction which was sent from heaven to Saint Paul teaches us. Thus the king is deprived of no inherited right, if there be made a provision in concordance with just law. For dissimulation shall not change the law, whose stable reason will stand without end. For this reason, if anything that is useful has been long put off, it is not to be criticized when adopted late. And let the king never set his private interest before that of the community, as if the salvation of all yields to him alone. For he is not set over them in order to live for himself; but that his people who are subject to him may be in safety. . . . Therefore if the prince will be warm with charity as much as possible toward the community, if he shall be solicitous to govern it well, and shall never rejoice at its destruction; wherefore if the king will love the magnates of the kingdom, although he should know alone, like a great prophet, whatever is needful for the ruling of the kingdom, whatever is becoming in him, whatever ought to be done, truly he will not conceal what he will decree from those without whom he cannot effect that which he will ordain. He will therefore negotiate with his people about bringing into effect the things which he will not think of doing by himself. . . . Oh! if princes sought the honor of God, they would rule their kingdoms rightly, and without error. If princes had the knowledge of God, they would exhibit their justice to all. Ignorant of the Lord, as though they were blind, they seek the praises of men, delighted only with vanity. . . . From all that has been said, it may be evident that it becomes a king to see, together with his nobles, what things are convenient for the government of the kingdom, and what things are expedient for the preservation of peace; and that the king have natives for his companions, not foreigners or favorites for his councillors or for the great nobles of the kingdom, who supplant others and abolish good customs. For such discord is a stepmother to peace, and produces battles, and plots treason. For as the envy of the devil introduced death [into the world], so hatred divides the troop. The king shall hold the natives in their rank, and by this governance he will have joy in reigning. But if he seeks to degrade his own people, if he perverts their rank, it is in vain for him to ask why, thus deranged, they do not obey him; in fact they would be fools if they did.

Questions: How is the account of the battle used to support the rightness of the barons’ cause? What does the baronial party want? What are the royalist arguments, and how does the author refute them? How is the political argument related to religious belief? How does this text compare with earlier articulations of royal power and its limits in the Policraticus (doc. 45) and Magna Carta (doc. 50)?

Fig. 33. Seals of Simon de Montfort and Eleanor de Montfort. Simon’s seal shows him engaged in the aristocratic pursuit of hunting, carrying a horn and accompanied by a hound. The seal of his wife Eleanor, which identifies her as countess of Leicester, likewise signals her high status through the inclusion of her family coat of arms.

57. The Miracles of Simon de Montfort

When Simon de Montfort was killed in battle at Evesham in 1265, royalists dismembered his body and distributed those grisly trophies to the earl’s enemies. The local canons of Evesham buried what remained of Simon’s corpse in their church, which became a shrine to the rebel leader; within a short time Simon was credited with hundreds of miracles, and many regarded him as a martyr. At the same time, as is clear from the miracles below, opinion about Simon’s cult remained divided, since he had died an excommunicate and rebel. As pilgrims began traveling to Evesham to take earth from the battlefield or visit the earl’s grave, Henry III moved to quash his adversary’s cult in the Dictum of Kenilworth, which forbade anyone to regard Simon as a saint or repeat stories of his “vain and fatuous marvels . . . on pain of bodily punishment.”

Source: trans. K.A. Smith from The Chronicle of William de Rishanger of the Barons’ Wars; The Miracles of Simon de Montfort, ed. J.O. Halliwell (London: Camden Society, 1840), pp. 69, 81, 84, 89–90, 92–93, 99–100, 109–10.

A sick woman from Elmley sent her daughter to draw water from the earl’s well [a spring said to have miraculously appeared on the battlefield at Evesham on the site of the earl’s death]. Returning from the well, the girl met some servants from the castle who asked what she had in her pitcher. She told them it was new beer from Evesham, but they replied, “No, you have water from the earl’s well.” They insisted on drinking some, whereupon they discovered that it was beer, as she had said, and let the girl go. But when she returned to her sick mother, it once again changed into water, which the infirm woman drank and was healed.

A certain miracle recounted to us by William, the rector of Werinton, is worthy of remembrance. After the Battle of Evesham, he collected some earth from the spot where the earl’s body had lain on the battlefield, and put it with some bread he had with him, and then gave the mixture as a holy sacrament to a mortally wounded layman. After the man had lain unconscious for two days, Earl Simon appeared to him in a dream and told him to ask the said William to take some of the hallowed earth and mix it with water for the wounded man to drink. And when this was done, the wounded man recovered.

John of Coventry, surnamed Farber, fell ill and died. When his wife saw the dead man, she cried out, “O Simon de Montfort, if you have done any good for God, and just as we believe you were martyred in the name of justice, show your power and restore this man!” And at once the dead man began to breathe again, and miraculously recovered after he had bent a penny [a symbolic promise to visit Simon’s shrine and offer a coin there]. The whole village of Coventry can attest to this.

William de la Horste of Bulne told the following story about his neighbor, Robert the deacon. In the second year after the Battle of Evesham, it happened that the said William held a great banquet. A quarrel broke out among the guests concerning the late earl, and Robert slandered the earl excessively, saying all manner of evil things about him. His host, William, warned him not to speak ill of the earl. At this moment Robert lost the power of speech and became paralyzed, so that he could only sit there like a corpse. After the other guests prayed for him, he began once again to breathe, and, taking William’s advice, promised to say nothing further against the earl. Thus he escaped from danger.

Stephen of Hull, Nicholas of Hull, John Good, and Walter Sygard, citizens of Hereford, recounted a miraculous story about Philip, chaplain of Brentley, who slandered the earl. This Philip declared, among other insulting things, “If Earl Simon is a saint, as they claim, let the devil break my neck, or some other miracle happen before I arrive home.” And so it happened just as he had asked, for as he was returning home by chance he saw a hare, and while chasing it he fell from his horse. He had been seized by a demon as punishment for insulting the earl; his sanity gone, he was seized and bound, and so has remained in chains from the feast of Saint John the Baptist to the translation of Saint Benedict, as the citizens of Hereford can attest.

Sir Osbert Giffard had long been suffering from a fever when, one night, Earl Simon appeared to him in a dream, telling him, “Find the armor which you took from me in battle, put it on, and you will be healed.” Upon waking, Osbert ordered his servants to search among the armor lying at the foot of his bed; they duly located the piece in question, put it on him, and so he was healed. The abbot of Evesham testifies to this, and he heard it from the mouth of Osbert himself.

Margaret, wife of William Mauncelle of Gloucester, who for some time had been an enemy of the earl, was struck by an affliction known as frenzy and went completely out of her senses for two days. Earl Simon appeared to her in a vision and asked her, “Why do you always speak ill of me?” Hearing this, that woman was moved to repent and beg his pardon for her wickedness. The earl pardoned her, and she asked him in turn what would happen to his enemies. He replied, “Some have repented, some will repent, and some will suffer an evil death without repenting.” After this, the woman was measured to Simon [so that she might offer a candle as long as her body at Simon’s shrine] and immediately recovered, as her neighbors testify.

A motet for the feast of Simon Montfort and his companions:

Save us, Simon Montfort,

Flower of all knighthood,

Who endured the harsh pains of death,

Protector of the English people.

The torments he endured while alive,

Were unheard of among the saints,

So great was his suffering!

His hands and feet cut off,

His head and body gravely wounded,

And his manly parts torn away.

Pray for us, Blessed Simon,

That we be made worthy of Christ’s promises.

Questions: What do the miracles tell us about the aftermath of the Second Barons’ War? Do these stories help explain why Henry III was so eager to suppress Simon’s cult? How do these miracles compare with those attributed to Thomas Becket (doc. 35)?

58. The Household Roll of Countess Eleanor of Leicester

The great households of medieval England were not only domestic spaces but venues for conspicuous consumption and hospitality, cultural patronage, and political maneuvering. In the thirteenth century it became customary for baronial households to keep written accounts of expenditures, and such records reveal how elites ate and drank, entertained, dressed, traveled, and maintained contact with friends and kin, while offering glimpses of humbler individuals—retainers, clerks, grooms, cooks, laundresses, messengers, and carters—whose labor kept great households running. This example details the expenditures of Eleanor, countess of Leicester and younger sister of King Henry III. In 1238 Eleanor secretly married the royal favorite Simon de Montfort, with whom she had seven children. When the Second Barons’ War broke out, Eleanor supported her husband against her royal brother. In the spring of 1265, the time period covered by these excerpts, Eleanor resided at Odiham Castle (Hampshire), a convenient base from which she remained in close contact with her husband, sons, and political allies. After her husband’s death at Evesham in August 1265, Eleanor fled to the French nunnery of Montargis, where she died a decade later.

Source: trans. M.W. Labarge, Mistress, Maids and Men: Baronial Life in the Thirteenth Century (London: Phoenix, 2003), pp. 195–201.

[Daily Expenditures]

On Saturday following [2 May], for the countess and the above-mentioned: Grain, 5 bushels of froille [wheat flour]. Wine, 2 sesters [a sester equals 4 gallons], 3 gallons. Ale, previously reckoned. Kitchen: 300 herring from the castle stores. Fish, 3s. 6d. For 600 eggs, 22½d. Stable: Hay for 30 horses. Oats, 1 quarter [a quarter equals 9 bushels]. 7 bushels from the constable’s purchase.

Sum, 5s. 4½d.

On Sunday following [3 May], for the countess and the above-mentioned: Grain, 6 bushels of froille. Wine, 3 sesters. Ale, previously reckoned. Kitchen: 1 ox and 1 pig from the castle stores; item, for 1 ox, 3 sheep, and 3 calves bought, 15s. 10d. Poultry, 5s. For 400 eggs, 15d. Milk for the week, 9 gallons from the castle. Stable: Hay for 30 horses. Oats, 2 quarters, 1 bushel from the constable’s purchase. For 4 geese bought, 16d.

Sum, 23s. 5d.

On Monday following [4 May], for the countess and the above-mentioned: Grain, 6 bushels of froille. Wine, 3 sesters; taken with Seman, ½ sester. Ale, previously reckoned. Kitchen: Meat and hens previously reckoned, and 1 fresh ox, from the castle stores. 300 eggs, 11 ¼d. Stable: Hay for 36 horses. Oats, 2 quarters, 3 bushels, from the constable’s purchase.

Sum, 11 ¼ d.

For the wages of the grooms, as appears on the back [of this roll], 15s. 2d. Grain for the poor for 8 days, ½ quarter, and 13 gallons of ale. Grain for the dogs for 10 days, 3 quarters.

Sum, 15s. 2d.

On Wednesday following [6 May], for the countess and the above-mentioned: Grain, 6 bushels of froille. Wine, 2½ sesters, ½ gallon. Ale, previously reckoned. Kitchen: Fish, 6s. 11d. Calf, 12d. For 400 eggs, 15d. Cheese for tarts, 9d. 50 herring from stores. Stable hay for 36 horses. Oats, 2 quarters, 3 bushels from the constable’s purchase.

Sum, 9s. 8d.

On Thursday following [7 May], for the countess and the above-mentioned: Grain, 6 bushels of froille. Wine, 2 sesters, 3 gallons. Ale, for 36 gallons, 17d. Kitchen: For 1 ox and 1 sheep, 7s. Calf, 10d. Hens, 2s. 6d. For 300 eggs, 11¼d. Stable: Hay for 36 horses. Oats, 2 quarters. 2 bushels from the constable’s purchase. Wax, from Friday the feast of Saint Mark [24 April; note that this is the clerk’s error; the feast fell on 25 April] until now, 13 pounds; for the chapel, 3 pounds. ½ pound of pepper for the foals.

Sum, 12s. 8¼ d.

On Friday following [8 May], for the countess and hers, and Sir Richard of Havering: Grain, 5 bushels of froille. Wine, 2 sesters, 3 gallons. Ale, for 160 gallons, 10s. at ¾d. per gallon; item, for 200 gals., 7s. 8d. at ½d. per gal. Kitchen: 250 herring from stores. Fish, 4s. 4d. Eggs, 6d. Stable: Hay for 36 horses. Oats, 2 quarters, 6 bushels from the constable’s purchase. For the carriage of ale, 4d.

Sum, 22s. 10d.

On Saturday following [9 May], for the Countess and hers: Grain, 5 bus. of froille. Wine, 2½ sesters; sent to Lady Catherine Lovel, 2 sesters; carried with Sir Richard the Chaplain, ½ sester. Ale, previously reckoned. Kitchen: 100 herring. Fish, 12s. 1d. Eggs 2s. 4d. 18 stockfish, for 3 days. Stable: Hay for 38 horses. Oats, 2 quarters, from the purchase of the constable.

Sum, 14s. 5d.

On Sunday following [10 May], for the countess, Lady Catherine Lovel being present: Grain, 6 bushels of froille. Wine, 4 sesters; sent with the above- mentioned Lady, ½ sester. Ale, previously reckoned. Kitchen: Carcasses, 6s. 8d. Lard, 16d. Poultry, 5s. 8d. Eggs, previously reckoned. For the expenses of the dogs in taking 1 stag, by Michael of Kemsing, 6d. Stable: Hay for 32 horses. Oats, 2 quarters from the constable’s purchase. For 4 geese 14 ½d.

Sum, 15s. 2½d.

For 2 quarters of malt wheat, 8 quarters, 2 bushels of malt barley, and 4 quarters of malt oats bought from Lady Wimarc of Odiham by the constable, soon after the countess’s arrival, 43s. 9½d. For the expenses of William the Carter going to Porchester with 3 horses, to obtain 1 tun [a tun equals 252 gallons] of wine, 3s.

Sum, 46s. 9½d.

Wax delivered to Sir Richard of Havering by order of the countess, 20 pounds; for the household, 3 pounds.

[Miscellaneous Payments]

By Gobion

| For 5 housings for the foals of the countess, bought by Richard Gobion | 4s. 2d. |

| For cart-clouts, grease, and small harness for the long cart | 20½d. |

| For the expenses of Robert de Conesgrave and 2 grooms with 2 horses, taking the robes of the king of Germany to Kenilworth, on Saturday after the finding of the Holy Cross [9 May] | 2s. |

By Seman

| For 1 new cart bought, bound with iron, and another repaired, by Seman, on Rogation Monday [11 May] | 34s. |

| Paid to John de Murcia, on the same day, by the same Seman | 10s. |