Chapter Five

An Age of Disasters, 1300–1399

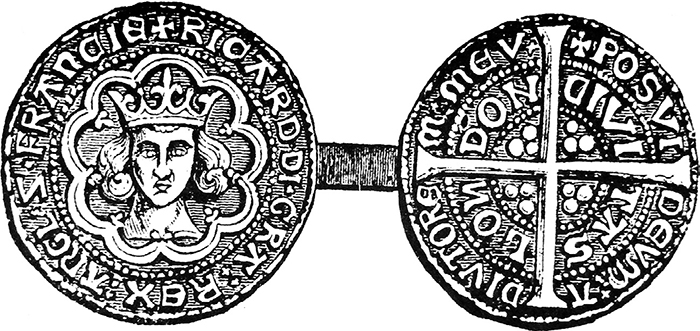

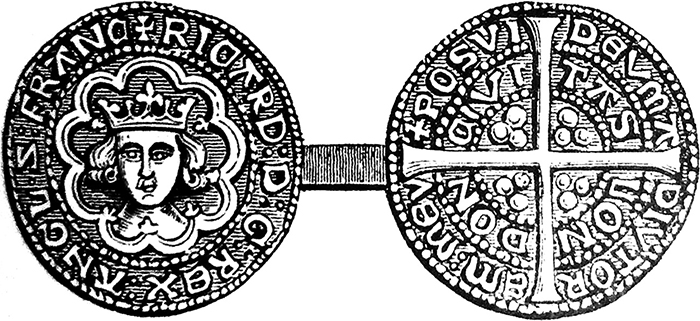

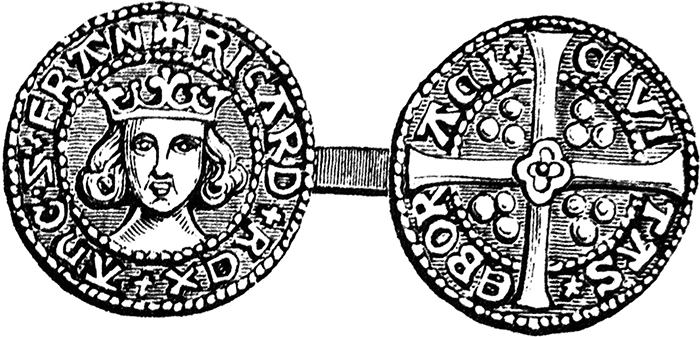

Fig. 35. Coins of Richard II. Through the twelfth century, the only coins minted in England were silver pennies. Larger denominations were introduced in the thirteenth century and became standard in the fourteenth. The groat was worth four pence; half-groats and gold coins worth 6s. 8d. (half a mark) were also used. These coins of Richard II, shown in nineteenth-century engravings, have the usual portrait of the current king on the front; the inscription on the obverse identifies the town or city where the coin was minted. The smallest is a penny minted at York; the others are a half-groat and groat minted at London.

67. Parish Life in the Diocese of Exeter

The religious lives of medieval laypeople focused on the parish church, where they attended mass with kin and neighbors, baptized their children, buried their dead, and celebrated feast days with processions and communal meals. The clergy were required to keep the church’s chancel (the east end which housed the altar) in good repair, while the parishioners maintained the nave (the west end) and churchyard, and furnished the service books, vestments, and mass implements necessary for the liturgy and sacraments. Each parish was under the authority of a bishop, who (at least in theory) sent out representatives to visit the parishes in his diocese. The following excerpts are from such a visitation to the diocese of Exeter in 1301.

Source: trans. G.G. Coulton, Social Life in Britain from the Conquest to the Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1918), pp. 260–62; revised, with additional material trans. K.A. Smith from The Register of Walter de Stapeldon, Bishop of Exeter (A.D. 1307–1326), ed. Rev. F.C. Hingestone-Randolph (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1892), pp. 107, 111.

Clyst Honiton. There is no psalter or antiphonary [a book containing chants for the divine office], the lectionary [a book of scriptural readings for the office] is badly bound, and the missal is in poor condition. There is no chalice, and the rest of what is in the church is insufficient for the service. The chancel is in terrible condition; a large portion of it has collapsed, so that the divine office cannot be celebrated properly at the high altar.

They [the parishioners] say that their parish priest is of honest life and good conversation, and has been there 22 years, honestly fulfilling his priestly office in all that pertains to a parish priest; but he is now broken with age and unable to carry out his duties in the parish. They further say a certain Alice, wife of Simon Luke, is a known adulteress, who freely gives herself to all who desire her, and that she often gave herself to a certain official on the manor of Poltimor. When this man arrived in the village there was a great uproar, so that Alice’s husband, fearing him, would not remain. Nor has the local firmarius [the official who collected rents due to the church on behalf of an ecclesiastical landlord, such as a bishop, and acted on the landlord’s behalf] corrected her, so that the parishioners fear that great harm will arise from their association with her, and appeal to the firmarius that Alice be corrected or removed.

Colyton. In the main church there is an adequate psalter, with a prayer book and capitulary [a book of readings for the office] for the use of the vicar, and another psalter for the use of the parishioners, which is old and of no value. . . . [The visitors list eight additional liturgical books in the church’s collection.] There is a large chalice, partly gilded, and another chalice of the same size for the altar of the Blessed Virgin, as well as a third, smaller one. There are five complete sets of vestments, and one which is lacking a stole, as well as one adequate cope [a cloak worn by a priest] and another that is old and in poor condition, and a tunic with a silk dalmatic. There are seven frontals [decorative cloth hangings] for the altar, as well as other ornaments: three banners, a hanging for use during Lent . . . two processional crosses made of metal, two small candelabra for processions, one worn surplice [a long tunic worn by a priest], another of no value, and a third in good condition, a lidded ivory pyx [a container for the consecrated host] missing its closure, a lead chrismarium [container for holy oil], and four ampullae. There is no lantern-tower, and the chancel lacks a proper roof.

They say that Sir Robert [Blond], their vicar, is an honest man and preaches to them as best he knows how, but not sufficiently, as they think. They say also that his predecessors were accustomed to call in the preaching friars to instruct them for the salvation of their souls; but this vicar does not care for them, and if by chance they do come, he will not receive them, nor give them any help; for which reason they beseech that he may be reprimanded. They further assert that all of the chaplains and clerks are of honest life, as well as chaste.

Dawlish. They say that the vicar, whom they hold to be a good man, does not reside personally in the parish, but has in his place Sir Adam, a chaplain, who bears himself well and honestly and teaches them excellently in spiritual things. But Randolph the Chaplain has kept his concubine for ten years or more, and though often rebuked, he persists incorrigibly. The parish clerk is continent and honest.

St. Mary’s Church. The parishioners say that, until the time of the present vicar, they were accustomed to keep the chancel in good repair and were immune from paying tithes for the restoration of the church; but the present vicar, though he does not maintain the chancel, still receives the tithe and compels them to pay. Item, they say that Agnes Bonatrix left 5 shillings in pollard coin [a coin worth half its face value] for the upkeep of St. Mary’s church, which the vicar received and still keeps. Item, Master le Roger left a certain sum of money to the same end, which the said vicar is said to have received in part. Item, they say that the vicar feeds his beasts in the churchyard, so that it is evilly trodden down and vilely defouled. Item, the said vicar takes for his own use the trees blown down in the churchyard. Item, he causes his malt to be malted in the church, where he also stores his wheat and other goods; and as a result his servants go in and out and leave the church door open, so that when it is stormy the wind blows into the church and damages the roof. They say, moreover, that he preaches well and exercises his office laudably in all things, when he is present. But often he goes to stay at Moreton-Hamptead for a week or two, so that they have no chaplain, except when Sir Walter, the archdeacon’s chaplain, is present, or some other casual chaplain is procured.

Questions: What did parishioners expect of their clergy? What tensions existed in these parishes? How different were the material conditions of wealthier churches and poorer ones? How might these differences have affected medieval parishioners’ experiences?

68. Correspondence of the Queen with London

The records of London include transcripts of many letters received, such as this one from Edward II’s queen, Isabel of France, announcing the birth of the future Edward III in 1312. The records also describe the celebrations that resulted.

Source: trans. H.T. Riley, Memorials of London and London Life in the XIIIth, XIVth, and XVth Centuries (London: Longmans, Green, & Company, 1868), pp. 105–7; revised.

“Isabel, by the grace of God, queen of England, lady of Ireland, and duchess of Aquitaine, to our well beloved, the mayor, and aldermen, and the commonalty of London, greeting. Since we believe that you would willingly hear good tidings of us, we make known to you that our Lord, of his grace, has delivered us of a son on the thirteenth day of November, with safety to ourselves, and to the child. May our Lord preserve you. Given at Windsor, on the day above-named.”

The bearer of this letter was John de Falaise, tailor to the queen; and he came on [14 November,] the Tuesday next after the feast of Saint Martin, in the sixth year of the reign of King Edward [II], son of King Edward [I]. But as the news had been brought by Robert Oliver on the Monday before, the mayor and the aldermen, and great part of the commonalty, assembled in the guildhall at the hour of Vespers [about six in the evening], and danced, and showed great joy at the news, and so passed through the city with great glare of torches, and with trumpets and other minstrelsies.

And on the Tuesday next, early in the morning, it was announced throughout all the city that there was to be no work, labor, or business in shop on that day, but that every one was to apparel himself in the most becoming manner that he could, and come to the guildhall at the hour of Prime [about six in the morning], ready to go with the mayor, together with the [other] good folks, to St. Paul’s, there to make praise and offering, to the honor of God, who had shown them such favor on earth, and to show respect for this child that had been born. And after this, they were to return all together to the guildhall, to do whatever might be enjoined.

And the mayor and the aldermen assembled at the guildhall, together with the good folks of the commonalty; and from there they went to St. Paul’s, where the bishop chanted mass with great solemnity on the same day; and there they made their offering. And after mass, they led carols in the church of St. Paul, to the sound of trumpets, and then each returned to his house.

On the Wednesday following, the mayor, by assent of the aldermen, and of others of the commonalty, gave to the said John de Falaise, bearer of the letter aforesaid, £10 sterling and a cup of silver, 4 marks in weight. And on the morrow, this same John de Falaise sent back the aforesaid present, because it seemed to him too little.

On the Monday following, the mayor was richly costumed, and the aldermen arrayed in like suits of robes; and the drapers, mercers, and vintners were in costume; and they rode on horseback from there to Westminster, and made their offering there, and then returned to the guildhall, which was excellently well tapestried and dressed out, and there they dined. And after dinner, they went out caroling throughout the city for all the rest of the day, and a great part of the night. And on the same day, the Conduit in Cheap ran with nothing but wine, for all those who chose to drink there. And at the cross just by the church of Saint Michael in West Cheap, there was a pavilion extended in the middle of the street, in which was set a tun of wine, for all passers-by to drink of, who might wish for any.

On [5 February, 1313,] the Sunday after Candlemas . . . , the fishmongers of London were costumed very richly, and they caused a boat to be fitted out like a great ship, with all manner of tackle belonging to a ship; and it sailed through Cheap as far as Westminster, where the fishmongers came, well mounted, and presented the same ship unto the queen. And on the same day, the queen set out for Canterbury, on a pilgrimage to that shrine; and the fishmongers, all thus costumed, escorted her through the city.

Questions: What kinds of activities are part of the celebrations? In what other ways is the city’s joy expressed? How are the people of London organized? Why is the celebration so large?

69. The Manner of Holding Parliament

This early fourteenth-century treatise is an interesting but not entirely accurate description of how Parliament operated. Though well informed on details of procedure, the anonymous author portrays Parliament as more standardized than it was in practice, and the first paragraph, on the origins of this thirteenth-century institution, is entirely fictitious. In an age when custom often had the force of law, claiming antiquity for current (or favored) practices was an effective way of promoting them. This author reveals himself as a supporter of broad representation and the power of Parliament as opposed to that of the king.

Source: trans. T.D. Hardy, Modus tenendi parliamentum; An Ancient Treatise on the Mode of Holding the Parliament in England (London: Eyre & Spottiswood, 1846), pp. 2–46; revised.

Here is described the way the Parliament of the king of England and his Englishmen used to be held in the time of King Edward [the Confessor], the son of King Æthelred; which method was recited by the more select men of the kingdom before William, duke of Normandy, both conqueror and king of England, the Conqueror himself commanding it, and it was approved by him and used in his own times, and also in the times of his successors, kings of England.

The Summoning of the Parliament

The summoning of the Parliament ought to precede the first day of the Parliament by forty days. . . .

Concerning Difficult Cases and Judgments

When any dispute, question, or difficult case, whether of peace or war, shall arise in or out of the kingdom, the case shall be related and recited in writing in full Parliament, and be dealt with and debated there among the peers of the Parliament, and if it be necessary it shall be enjoined by the king, or on his behalf if he is not present, to each rank of peers, that each rank proceed by itself, and the case shall be delivered in writing to its clerk, and in an appointed place they shall cause him to recite the case before them, so that they may order and consider among themselves how it may be better and more justly proceeded in as they shall be willing to answer before God for the king’s person and their own persons, and for the persons of those whom they represent; and they shall report their answers and advice in writing, so that, all their answers, counsel, and advice being heard on all sides, it may be proceeded in according to the best and soundest counsel, and where at least the major part of Parliament agrees. . . .

Concerning the Business of the Parliament

The business for which the Parliament is held ought to be deliberated on according to the calendar of Parliament, and according to the order of petitions delivered and filed, without respect to persons, but who first proposes shall first act. In the calendar of Parliament all business of the Parliament ought to be regarded in the following order: first, concerning war, if there be war, and other affairs touching the persons of the king and queen and their children; secondly, concerning the common affairs of the kingdom, such as making laws against the defects of original laws, judicial and executorial, after judgments rendered, which are chiefly common affairs; thirdly, private business ought to be considered, and this according to the order of the filing of petitions as is aforesaid.

Concerning the Days and Hours of Parliament

The Parliament ought not to be held on Sundays, but it may be held on all other days, except three, namely All Saints [1 November], All Souls [2 November], and the nativity of Saint John the Baptist [24 June]. And it ought to begin at midprime on each day, at which hour the king and all the peers of the realm are bound to be present at the Parliament; and the Parliament ought to be held in a public and not in a private or obscure place. On festival days the Parliament ought to begin at the hour of prime [the first hour of daylight] on account of divine service.

Concerning the Ranks of Peers

The king is the head, beginning, and end of Parliament, and he has no peer in his rank, and so the first rank consists of the king alone; the second rank is that of the archbishops, bishops, abbots, and priors holding by barony; the third rank is of the procurators of the clergy; the fourth is of the earls, barons, and other magnates and nobles, holding land to the value of a county or barony . . . ; the fifth is of the knights of shires; the sixth is of the citizens and burgesses. And so Parliament is composed of six ranks. But it must be known that even if any of the said ranks, below the king, is absent, if they have been summoned by reasonable summonses of Parliament, the Parliament shall nevertheless be considered complete.

Concerning the Opening of the Parliament

The lord king shall sit in the middle of the larger bench, and is bound to be present at prime, on the sixth day of the Parliament. And the chancellor, treasurer, barons of the exchequer, and justices are accustomed to record defaults made in Parliament in the following order: on the first day the burgesses and citizens of all England shall be called over, on which day if they do not come, a borough shall be amerced 100 marks and a city £100; on the second day the knights of shires of all England shall be called, on which day if they do not come, their county shall be amerced £100; on the third day of the Parliament the barons of the Cinque Ports shall be called, and afterward the barons, and afterward the earls, when, if the barons of the Cinque Ports do not come, the barony from which they were sent shall be amerced 100 marks; in the same manner a baron by himself shall be amerced 100 marks, and an earl £100; in like manner shall be done with those who are peers of earls and barons . . . ; on the fourth day the procurators of the clergy shall be called, on which day if they do not come, their bishops shall be amerced 100 marks for every archdeaconry making default; on the fifth day the deans, priors, abbots, bishops, and lastly the archbishops, shall be called, who, if they do not come, shall be amerced each archbishop £100, a bishop holding an entire barony 100 marks, and in like manner with respect to the abbots, priors, and others. On the first day proclamation ought to be made, first in the hall or monastery, or other public place where the Parliament is held, and afterward publicly in the town or village that all who wish to deliver petitions and complaints to the Parliament may deliver them from the first day of the Parliament for the next five days.

Concerning the Preaching before the Parliament

An archbishop, or bishop, or eminent, discreet, and eloquent clerk, selected by the archbishop in whose province the Parliament is held, ought to preach on one of the first five days of the Parliament in full Parliament, and in the presence of the king, and this when the greater part of the Parliament is assembled and congregated, and in his discourse he ought in due order to enjoin the Parliament that they with him should humbly beseech God and implore him for the peace and tranquility of the king and kingdom. . . .

Concerning the Declaration in Parliament

After the preaching the chancellor of England, or the chief justice of England, that is, he who holds pleas before the king, or some fit, honorable, and eloquent justice or clerk elected by the chancellor and chief justice, ought to declare the causes of the Parliament, first generally, and afterward specially, while standing. And it is to be observed that all in Parliament, whoever they are, shall stand while they speak, except the king, so that all in Parliament may be able to hear the speaker. And if he speaks obscurely or in a low voice he shall speak over again and louder, or another shall speak for him.

Concerning the King’s Speech after the Declaration

The king, after the declaration for the Parliament, ought to entreat the clergy and laity, naming all their degrees, that is, the archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors, archdeacons, procurators, and others of the clergy, the earls, barons, knights, citizens, burgesses, and other laymen, that they diligently, studiously, and cordially will labor to deal with and deliberate on the affairs of Parliament as they shall think and perceive how this may best and principally be done, in the first place according to God’s will, and afterward for the king’s and their own honor and welfare.

Concerning the King’s Absence from Parliament

The king is bound by all means to be personally present in Parliament, unless hindered by bodily infirmity, and then he can keep to his chamber, as long as he does not lie out of the manor or at least the town where Parliament is held, and then he ought to send for twelve of the greater and better persons who are summoned to Parliament, that is, two bishops, two earls, two barons, two knights of shires, two citizens, and two burgesses to visit him and testify about his condition. . . . The reason is that clamor and murmurs used to arise in Parliament on account of the king’s absence, because it is a hurtful and dangerous thing for the whole commonalty of Parliament, and also for the realm, when the king is absent from the Parliament. . . .

Concerning the Places and Seats in the Parliament

First, as is aforesaid, the king shall sit in the middle place of the greater bench, and on his right hand shall sit the archbishop of Canterbury, and on his left hand the archbishop of York, and immediately after them the bishops, abbots, and priors in rows, with the ranks and places always so arranged that each one sits among his peers; and the steward of England is bound to attend to this, unless the king appoint another person. At the king’s right foot shall sit the chancellor of England and the chief justice of England, and his associates, and their clerks who are of Parliament, and at his left foot shall sit the treasurer, chamberlain, barons of the Exchequer, justices of the bench, and their clerks who are of Parliament. . . .

Concerning the King’s Aid

The king is not accustomed to ask aid from his kingdom except for approaching war, or making his sons knights, or marrying his daughters, and then such aids ought to be asked in full Parliament, and delivered in writing to each rank of peers of the Parliament, and answered in writing. . . .

Concerning the Breaking Up of the Parliament

The Parliament ought not to disband as long as any petition remains which has not been discussed, or at least to which the answer is not determined on, and if the king permits the contrary he is perjured. And no single one of the peers of the Parliament can or ought to retire without having obtained the permission of the king and all his peers, and this in full Parliament, and a record of this permission shall be entered in the roll of the Parliament. And if any one of the peers is sick during the Parliament, so that he cannot attend, then for three days he shall send excusers to the Parliament. And if he does not come on the third day, two of his peers shall be sent to see and testify to his sickness, . . . and if it be found that he has feigned illness he shall be amerced as if for default, and if he has not feigned then he shall appoint some sufficient person before them to be present at the Parliament for him. . . .

The separation of the Parliament used to be in this manner: it ought first to be asked and publicly proclaimed in the Parliament, and within the palace of the Parliament, if there be anyone who shall have delivered a petition to the Parliament to which no answer has yet been given, or at least been answered as far as can be rightly done, and if no one shall answer, it is to be supposed that remedy has been afforded to everyone, and then, that is, when no one who at that time has exhibited his petition shall answer, [the king shall say,] “We will release our Parliament.”

Questions: What political beliefs and sympathies underlie this description? What is the balance of power between Parliament and the king? Between the different groups that make up Parliament? What practical matters are dealt with here? What role does religion play?

70. A Chronicle of the Great Famine

In the early fourteenth century a terrible natural disaster overtook northern Europe when several years of inordinately rainy weather led to repeated massive crop failures and widespread famine. Marginal farmland had to be abandoned, animals could not be fed, many people starved, and a long period of population growth came to an end. In these brief extracts from the anonymous Life of Edward the Second, the chronicler pauses in his account of wars and politics to comment on the catastrophe and its effects.

Source: trans. N. Denholm-Young, The Life of Edward the Second by the So-Called Monk of Malmesbury (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons., 1957), pp. 59, 64, 69–70, 90.

Then at the Purification of the Blessed Mary [2 February, 1315] the earls and all the barons met at London, . . . and [the meeting] dragged on almost to the end of Lent [in the middle of March].

In this Parliament, because merchants going about the country selling victuals charged excessively, the earls and barons, looking to the welfare of the state, appointed a remedy for this malady; they ordained a fixed price for oxen, pigs and sheep, for fowls, chickens, and pigeons, and for other common foods. . . . These matters were published throughout the land, and publicly proclaimed in shire courts and boroughs. . . .

By certain portents the hand of God appears to be raised against us. For in the past year there was such plentiful rain that men could scarcely harvest the corn or bring it safely to the barn. In the present year worse has happened. For the floods of rain have rotted almost all the seed, so that the prophecy of Isaiah might seem now to be fulfilled; for he says that “ten acres of vineyard shall yield one little measure and thirty bushels of seed shall yield three bushels” (Isaiah 5:10), and in many places the hay lay so long underwater that it could neither be mown nor gathered. Sheep generally died and other animals were killed in a sudden plague. It is greatly to be feared that if the Lord finds us incorrigible after these visitations, he will destroy at once both men and beasts; and I firmly believe that unless the English Church had interceded for us, we should have perished long ago. . . .

After the feast of Easter [in 1316] the dearth of corn was much increased. Such a scarcity has not been seen in our time in England, nor heard of for a hundred years. For the measure of wheat sold in London and the neighboring places for 40d., and in other less thickly populated parts of the country 30d. was a common price. Indeed, during this time of scarcity a great famine appeared, and after the famine came a severe pestilence, of which many thousands died in many places. I have even heard it said by some, that in Northumbria dogs and horses and other unclean things were eaten. For there, on account of the frequent raids of the Scots, work is more irksome, as the accursed Scots despoil the people daily of their food. Alas, poor England! You who once helped other lands from your abundance, now poor and needy are forced to beg. Fruitful land is turned into a salt marsh; the inclemency of the weather destroys the fatness of the land; corn is sown and tares are brought forth. All this comes from the wickedness of the inhabitants. Spare, O Lord, spare thy people! For we are a scorn and a derision to them around us. Yet those who are learned in astrology say that these storms in the heavens have happened naturally; for Saturn, cold and heedless, brings rough weather that is useless to the seed; in the ascendant now for three years he has completed his course, and mild Jupiter duly succeeds him. Under Jupiter these floods of rain will cease, the valleys will grow rich in corn, and the fields will be filled with abundance. For the Lord shall give that which is good and our land shall yield her increase. . . .

[In 1318] the dearth that had so long plagued us ceased, and England became fruitful with a manifold abundance of good things. A measure of wheat, which the year before was sold for 40d., was now freely offered to the buyer for 6d. . . .

Questions: What explanations for the disaster are offered? What were the effects of the poor weather? What attempts were made to limit the damage? After weather conditions returned to normal in 1318, might there have been any long-term effects for individuals and for society?

71. The Royal Response to the Famine

As indicated in the previous piece, price controls were the royal government’s response to the inflation caused by the scarcity of food.

Source: trans. C.W. Colby, Selections from the Sources of English History (New York: Longmans, Green & Company, 1913), pp. 92–93.

Edward [II], by the grace of God, king of England, lord of Ireland, and duke of Aquitaine, to the mayor and sheriffs of London, greeting. We have received a complaint of the archbishops, bishops, earls, barons, and others of the commonalty of our kingdom, presented before us and our council, that there is now a great and intolerable dearth of oxen, cows, sheep, hogs, geese, hens, capons, chickens, pigeons, and eggs, to the great damage and grievance of them and all others living within the said kingdom. For this reason, they have urgently beseeched us to provide a fit remedy for this situation. We therefore, for the common benefit of the people of the said kingdom, assenting to the aforesaid supplication, as seemed meet, have ordained, by the advice and assent of the prelates, earls, barons, and others, being of our council, in our last Parliament held at Westminster, that a good saleable fat live ox, not fed with grain, be henceforth sold for 16s. and no more; and if he have been fed with corn, and be fat, then he may be sold for 24s. at the most; and a good fat live cow for 12s. A fat hog of two years of age for 40d. A fat sheep with the wool for 20d. A fat sheep shorn for 14d. A fat goose in our city aforesaid for 3d. A good and fat capon for 2½d., . . . and three pigeons for 1d., and twenty eggs for 1d. And that if any person or persons are found unwilling to sell the said goods at the settled prices, then let the goods be forfeited to us. And since we will that the foresaid ordinance be henceforth firmly and inviolably kept in our said city and its suburbs, we strictly order and command you to have the foresaid ordinance proclaimed publicly and distinctly in our foresaid city and its suburbs, where you think fit, and to be henceforth inviolably kept, in all and each of its articles, throughout your whole liberty, under penalty of the foresaid forfeiture. By no means fail to do this if you wish to avoid our indignation and save yourselves from harm. Witness ourself at Westminster, the fourteenth day of March, in the eighth year of our reign.

Questions: What are the king’s reasons for making this proclamation? What specific effects of the poor weather are cited? What provisions are made for the enforcement of the order? How severe are the proposed penalties?

72. Manor Court Rolls

On every manor in England, the manor court enforced the lord’s rights over his tenants, dealt with disputes between residents, and tried minor criminal cases; thus the records kept of these sessions during the late Middle Ages provide a window onto medieval rural societies and economies. The extracts below come from Great Cressingham in Norfolk, in the years 1328–29.

Source: trans. H.P. Chandler, Five Court Rolls of Great Cressingham, in the County of Norfolk (privately printed, 1885), repr. in Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History, Series 1, vol. 3, ed. E.P. Cheyney (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Department of History, n.d.) no. 5, pp. 20-24; revised.

A Court in [Great Cressingham], on [12 September, the] Monday next after the feast of the nativity of the Blessed Mary in the year of the reign of King Edward above mentioned [1328].

Excuse. William of Glosbridge, attorney of Sir Robert de Aspale by the common excuse through W. Prat. [He came afterward.]

Order. It was ordered, as before, to distrain [seize some of his property in order to compel] Master Firmin to show by what right, etc., concerning the tenement Walwayn. Likewise to distrain Sir John Walwayn for fealty.

Amercement [a monetary penalty], 3d. From Petronilla of Mintling for leave to agree with William Attewent, concerning a plea of trespass.

Order. It was ordered to distrain Peter the Cooper for 15d. which he owed to Roger the Miller, at the suit of William Attestreet, who proved against him 4s. in court.

Fine [payment to settle a dispute], 12d. From Walter Orengil for his term of four years to hold 6 acres of land rented from Gilbert Cloveleek, for which grant the said Walter is to pay annually, at the feast of All Saints [1 November], to the said Gilbert four quarters and four bushels of barley, during the said term. Pledges Nally and John Buteneleyn.

Amercement, 2d. From John Brichtmer because he was summoned to do one boon-work [work owed to the lord by an unfree peasant] in autumn and did not come. Therefore he is to be amerced.

Amercement, 2d. From Alice, wife of Richard of Glosbridge, for the same.

Amercement, 2d. From William Robin for the same.

Order. From Walter Page and Margaret his wife, because they cannot deny that they are keeping back from John of Enston 3d., and therefore it was ordered that the said 3d. should be levied from the said Walter to the use of the said John. (Reversed, because he is poor.)

Fine, 4d. Martin the son of Basil and Alice his wife having been examined by the bailiff, surrendered into the lord’s hand one rood of land with a cottage upon it, to the use of Isabel daughter of John Fayrsay and their heirs, to hold in villeinage at the will of the lord, doing etc., all rights being saved [not making any change in basic status and obligations]. And she gives, etc.

Fine, 4d. Isabel Fayrsay surrendered into the lord’s hands one rood and one quarter of a rood of land and one rood of meadow and half of a cottage to the use of Martin Basil’s son and Alice his wife and their heirs, to hold in villeinage at the will of the lord, doing etc. All rights being saved. And he gives to the lord [etc.].

Fine, 4d. From John Pye for his term of five years to hold in three roods of land rented from Hugh Holer. The term begins at the feast of Saint Michael [29 September].

Fine, £4. It is to be remembered that the lord out of his seisin delivered and gave to Vincent of Lakenham one messuage [a dwelling], 7 acres, and 2½ roods of land of the villeinage of the lord, which had been taken into the lord’s hand after the death of William the son of Hugh because the aforesaid William was a bastard son and died without heirs, to hold of him to the aforesaid Vincent and his heirs, in villeinage at the will of the lord, doing the services and customs due for it. All rights being saved. And he gives to the lord for his entry. And saving to Alice who was the wife of Hugh the son of Lawrence half of the said tenements to hold in dower for the term of her life.

Note, 1 beast; price 10s. The jury says John Bassisson has died seized of one messuage, 16 acres and 1 rood of land in villeinage, and that John his son is his next heir, and is nine years of age. And because the said heir has not come, therefore it is ordered that seisin be in the whole villeinage until, etc.

Order. To distrain the tenants of the tenement Sowle for one boon-work withheld in autumn.

Fine, 40s. All the jury says that Thomas Ode has died seised of a cottage and 5 acres and one rood of land of the villeinage of the lord, and that they know him to have no surviving heir, and therefore the whole tenement was taken into the lord’s hand. And the lord out of his seisin delivered and gave the whole of the said tenement to a certain Simon Maning of Walton and his heirs to hold in villeinage at the will of the lord, doing the service and customs due for it. Saving all kinds of rights. And he gives to the lord to have entry.

Order. Ordered to distrain Henry Cook, John Maggard, chaplain, and John Ingel, because they withhold from the lord 3d. rent now for five years for the parcel tenement Merchant.

Likewise to distrain Richard of the River for fealty for the tenement formerly of Reyner Attechurch.

Election. The whole homage elect the tenement of Geoffrey Attechurchgate for the office of reeve this year, and the tenants are Nally, Buteneleyn, Martin, Bassisson, and others. . . .

Amercement, 12d. From William Hubbard for damage in the lord’s meadows.

Amercement, 6d. From John Aylmer for damage in the fields in autumn.

Amercement, 2d. From Hugh Holer because he did not do his boon-work in autumn, as he was summoned to do.

12d. From Isabel Syapping for license to have a fold of her own sheep.

Memorandum. Of 4 bushels of barley taken from Roger the miller, etc., by the Reaper; and let them be handed over to Thomas Pawe for a debt recovered against the said Roger.

Total £6 4s. 11d., besides a heriot [death tax] valued at 10s.

Total of all the courts for the whole year, £8 16s. 8d.

Cressingham. A court and leet [a manorial court] there on [3 July 1329, the] Monday next after the feast of the apostles Peter and Paul, in the third year of the reign of King Edward, the third from the Conquest. . . .

Fine, 18d. Gilbert de Sedgeford surrendered into the hands of the bailiff, in the presence of the whole homage, a cottage to the use of John Putneys and his heirs, to hold in villeinage at the will of the lord, doing the services and customs due for it; saving rights of all kinds. And he gives for entry, etc.

Order. It was ordered to retain in the lord’s hand one messuage and one acre of land of which John Belesson was seized when he died, because it is not known of what condition he was; and therefore the rolls of the 34th and 32nd [years] of King Edward [II] are being examined.

Amercement, 3d. From Alice, daughter of Geoffrey Attenewhouse, for marrying without leave.

Amercement, 4d. From John, son of Martin, for the same.

Postponement. A suit between Thomas Attetunsend, plaintiff, and Adam Attewater, defendant, concerning a plea of agreement, was postponed till the next court by consent of the parties on account of arbitration.

Postponement. A distraint taken from John Maggard and Henry Cook for arrears of rent was postponed till the next court. And it was ordered to distrain John Ingel, their joint-tenant, etc.

Chief Pledges: John Buteneleyn, John Hardy, William Robin, Thomas Hardy, Henry Pawe, Nicholas, son of Roger, Laurence Smith, Roger Attehallgate, Roger Gumay, William le Warde, William Attestreet, Robert Gemming. These were sworn and say:

Fine, 3d. From William Hubbard for license to put his grain, growing in the lord’s villeinage, out of villeinage.

Amercement. From Silvester Smith, for blood drawn from John Marschal. [Erased.] Because he was elsewhere.

Amercement, 6d. From John Barun for the same from William, son of Sabina.

Amercement, 3d. From Margaret Millote for the same from Agnes, daughter of Martin Skinner.

Amercement, 6d. From the rector for an encroachment on the common at Greenholm, 12 perches long and 2 feet wide.

Amercement, 6d. From the same rector for an encroachment made at Caldwell, 20 perches long and 11 feet wide.

Amercement, 3d. From Roger of Drayton because he made an encroachment at the Strete 3 perches [49½ feet] long and 1 foot wide. . . .

Amercement, 6d. From Hugh Reff and Hugh Holer for license to resign the office of ale-taster.

Election. Alan Cook and Alan Spicer were elected to the office of ale-taster, and sworn.

Amercement, 2d. From Christiana Punt because she has sold ale and bread contrary to the assize.

Amercement, 2d. From William, son of Clarissa, because he broke into the house of John son of Geoffrey Brichtmer.

Amercement, 2d. From Adam son of Matilda Thomas because he is not in the tithing.

Amercement, 2d. From John son of Thomas Brun for the same.

Amercement, 6d. From Peter Miller for a hue and cry justly raised against him by the wife of William Fuller.

Questions: What different ranks of people and their occupations appear in the record? How do women figure in these proceedings? What laws and legal obligations are mentioned? What kinds of disputes are brought to the court?

73. A Proof of Age Inquest

Beginning in the late twelfth century, heirs to lands held directly from the king could not inherit until they proved they had reached the age of majority: twenty-one for men, fourteen for women. In the absence of standardized birth records, an heir’s age was determined through an inquest overseen by a royal official called an escheator, who heard testimony by kin, servants, and neighbors who claimed to remember the birth of the young man or woman. Such testimonies are rich sources for everyday life, and demonstrate the continued value of oral traditions in a society moving toward a greater emphasis on written records.

Source: trans. J.E.E.S. Sharp, Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem and Other Analogous Documents Preserved in the Public Record Office, Vol. 7: Edward III (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1909), pp. 139–41; revised.

Richard Henriz, son and heir of Richard Henriz, deceased, who held of King Edward II, [as a tenant] in chief. Writ to the escheator to take the proof of age of the said Richard, whose lands are in the wardship of John de Mounteney by the said king’s commission . . . November, 2 Edward III [1329, the second year of Edward’s reign].

Proof of age inquest held Thursday next before Christmas, 2 Edward III, at Derby.

John de Brokestouwe, aged 50 years and more, says that on the morrow of Saint Leonard, 1 Edward II [1307, the first year of Edward II’s reign], the said Richard was born at Stapelford, Derbyshire, in the manor-house of the said town, in the large stone chamber by the hall, and was baptized in the church of St. Helen’s there, and that Sir Richard, then prior of Newstead in Sherwood, and William de Cobbeleye, then chaplain of the parish, lifted him from the sacred font. On the morrow of Saint Leonard last, the aforesaid Richard was 21 years of age, and this he knows because King Edward II was crowned at Westminster on Sunday next after the Purification next before the aforesaid feast of Saint Leonard.

Geoffrey de Brinsley, aged 48 years, says the same, and knows it because, on Sunday next after the Purification, 1 Edward II, before the said feast of Saint Leonard, the same king married Isabella, queen of England, at Westminster, and the witness passed the night before the celebration of the said nuptials at the Tower of London.

Roger de Manchester, aged 50 years and more, says the like, and knows it because on Saturday next after the feast of Saint Mark in the same year, Roger Hare slew Robert Daubeney in Stapelford, and on Saturday next before the feast of Saint Mark last 21 years will have elapsed.

John de Burton, aged 42 years, says the same, and knows it because on Wednesday the next before Saint Nicholas, 1 Edward II, he left the school of Nottingham by the advice of Thomas de Stapelford, rector of the church of Trowell, and became clerk with the said Thomas from the aforesaid day to the same day 7 years later, on which day he married Joan, daughter of Nicholas de Sandiacre, with whom he has now lived for 14 years.

John de Strelley, aged 60 years, agrees, and knows it because at that time he was bailiff for Robert de Strelley, knight, of the manor of Shipley, Derbyshire, and on Thursday next before the feast of Saint Edmund, king and martyr, 1 Edward II, there came robbers by night to the said manor, and made assault, and while he was defending the manor one of the robbers struck him through the middle of the arm with an arrow.

Hugh Abbot, aged 50 years, agrees, and knows it because on Sunday next after the feast of Saint Leonard, 1 Edward II, he had a son, Robert, born and baptized and dead on the same day, 21 years ago.

William Torcard, aged 60 years, agrees with the said Hugh, and knows it because his mother Margery died on Saint Swithun’s day in the year following, and on the same feast it will be 22 years ago.

William Esthwaite, aged 40 years, agrees with the same William Torcard, and knows it because on the day after the feast of Saint Andrew, 1 Edward II, his daughter Alice was espoused to Robert de Bilburgh, and at the feast of Saint Andrew last 21 years had elapsed since then.

Geoffrey, son of Richard, aged 50 years, agrees with the said William Esthwaite, and knows it because on the day on which the said Richard Henriz was born, namely on the morrow of Saint Leonard, 1 Edward II, the said Geoffrey had a son named Richard, who celebrated his first mass in the parish church of Stapelford on the same day.

John Gerveys, of Chilwell, aged 40 years, agrees with Geoffrey, son of Richard, and knows it because on the third day after the birth of the said Richard, viz., on the fourth day after the feast of Saint Leonard, 1 Edward II, his wife Cecily was engaged for the nourishment of the aforesaid Richard, and stayed three days as his wet-nurse. But the stay did not please her, for on the fourth day she withdrew from her service and returned home to her husband.

Robert, son of Thomas of Bramcote, aged 52 years, agrees with the said John, and knows it because on the Sunday before Saint Leonard, 1 Edward II, his firstborn son Roger was born, and on Sunday before the said feast last past the said Roger was 21 years of age.

Stephen Paule, aged 43 years, agrees with the said Robert, and knows it because on the morrow of Saint Leonard, 1 Edward II, he received the office of bailiff of the honor of Peverell, by the demise of Richard Martel, and by the date of his commission he has knowledge of the age of the said Richard.

John de Mounteney, being warned to be present at the taking of this proof, did not appear, nor did any one on his behalf, to show cause why the said lands and tenements should not be restored to the aforesaid Richard Henriz, as of full age.

Questions: How were witnesses able to recall dates over two decades in the past? What role did written records play in the inquest? What do we learn about how medieval people situated themselves in time?

74. London Craft Guild Ordinances

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, urban practitioners of each craft or industry banded together in craft guilds that regulated their businesses, set quality standards and prices, and determined who was eligible to work in the craft.

Source: trans. H.T. Riley, Memorials of London and London Life in the XIIIth, XIVth, and XVth Centuries (London: Longmans, Green, & Company, 1868), pp. 226–28, 372–73; revised.

Articles of the Spurriers, 1345

In the first place, that no one of the trade of spurriers shall work longer than from the beginning of the day until curfew is rung out at the church of St. Sepulcher [at nine or ten at night], outside Newgate, by reason that no man can work so neatly by night as by day. And many persons of the said trade, who know how to practice deception in their work, desire to work by night rather than by day: and then they introduce false iron, and iron that has been cracked, for tin, and also, they put gilt on false copper, and cracked. And further, many of the said trade are wandering about all day, without working at all at their trade; and then, when they have become drunk and frantic, they take to their work, to the annoyance of the sick and of all their neighborhood, as well by reason of the fights that arise between them and the strange folk who are dwelling among them. And then they blow up their fires so vigorously, that their forges begin all at once to blaze, to the great peril of themselves and of all the neighborhood around. And then too, all the neighbors are much in dread of the sparks, which so vigorously issue forth in all directions from the mouths of the chimneys in their forges. By reason whereof, it seems unto them that working by night [should be ended,] in order to avoid such false work and such perils. . . . And if any person shall be found in the said trade to do to the contrary, let him be amerced, the first time for 40d., one half thereof to go to the use of the chamber of the guildhall of London, and the other half to the use of the said trade; the second time, in half a mark, and the third time, for 10s., to the use of the same chamber and trade; and the fourth time, let him forswear the trade forever.

Also, that no one of the said trade shall keep a house or shop to carry on his business, unless he is free of the city; and that no one shall cause to be sold, or exposed for sale, any manner of old spurs for new ones; or shall garnish them, or change them for new ones.

Also, that no one of the said trade shall take an apprentice for a term of less than seven years; and such apprentice shall be enrolled, according to the usages of the said city. . . .

Also, that no one of the said trade shall receive the apprentice, serving-man, or journeyman of another in the same trade, during the term agreed between his master and him, on the pain aforesaid.

Also, that no alien of another country, or foreigner of this country, shall follow or use the said trade, unless he is enfranchised before the mayor, aldermen, and chamberlain; and that, by witness and surety of the good folks of the said trade, who will undertake for him as to his loyalty and his good behavior.

Also, that no one of the said trade shall work on Saturdays, after Nones has been rung out in the city; and not from that hour until the Monday morning following.

Ordinances of the Court-Hand Writers, or Scriveners, 1373

Unto the honorable lords, the mayor and aldermen of the city of London, the writers of court-hand of the same city pray that, whereas their craft is very much in demand in the city, and as it is especially necessary that it should be ruled and followed lawfully and wisely and by persons instructed therein, and seeing that, for lack of good rule, many mischiefs and defaults are, and have often been committed in the said craft, by those who hailing from various countries, both chaplains and others, have no knowledge of the customs, franchises, and usages of the city, and who cause themselves to be called “scriveners,” and undertake to make wills, deeds, and all other things touching the said craft; the fact being that they are foreigners and unknown, and also are less skilled than the aforesaid scriveners who are free of the said city, and who for long have been versed in their craft, and have largely given of their means for their instruction and freedom therein: to the great damage and disinheritance of many persons, as well of the said city as of many countries of the realm, and to the great damage and scandal of all the good and lawful men of the said craft—therefore the good scriveners pray that it may please your honorable and discreet lordships, to grant to them, and to establish for the common profit of the said city, and of many other countries, and for the well-being and amendment of their condition, that they, and their successors for all time, may be ruled and may enjoy their franchise in their degree in manner as other folks of diverse trades of the said city are ruled and do enjoy their franchise, in their degree; according to the following points.

In the first place, they pray that no person shall be suffered to keep shop of the said craft in the city, or in the suburb thereof, if he be not free of the city, made free in the same craft, and that, by men of the craft.

Also, that no one shall be admitted to such freedom, if he be not first examined and found able by those of the same craft who shall, for the time being, by you and your successors be assigned and deputed to do the same, and to be wardens of the said craft.

Also, that every scrivener of the said city, and of its suburbs, shall put his name to the deeds which he makes, so that it may be known who has made the same.

Also, that every one who shall act against this ordinance and enactment, shall pay to the chamber the first time 40d.; the second time, half a mark; and the third time, 10s.

Also, that these articles shall be enrolled in the said chamber, as being firm and established forever.

Questions: What do we learn about the London economy and the functions of craft guilds? How did the crafts present themselves? In what ways did the guilds both support and restrict their members?

75. Urban Environmental Problems and Regulations

Crowded conditions and industrial processes led to serious environmental problems in medieval English towns like London. The concentration of human and industrial wastes caused particular problems for both inhabitants and authorities, who had to balance economic, safety, and quality-of-life concerns through legislation, litigation, and other means.

Source: trans. H.T. Riley, Memorials of London and London Life in the XIIIth, XIVth, and XVth Centuries (London: Longmans, Green, & Company, 1868), pp. 171–72, 225–26, 295–96, 339–40; revised.

Unlawful Nets Condemned to Be Burned, 1329

. . . [On 19 April], in the third year of the reign of King Edward III, there came Estmar Coker and John Wychard, citizens of London, together with Ralph Bourghard, serjeant of the chamber of guildhall, and brought before the mayor and aldermen at the guildhall, John Jacob of Rith [and seven other] fishermen, because they had been found fishing in the water of Thames with twelve nets which are known as “tromkeresnet,” and are a kind of kidel: the meshes of which nets—which are called mascles—ought to be one inch and a half in size, whereas these were hardly half an inch; and with which nets the said fishermen caught every fish, and even every little fish that entered such nets. Thus the small fish, which are called fry, were unable to escape from the said nets, to the great damage of all the people of the city, and also, of others resorting to the same city.

And the said John Jacob and others, being questioned as to this, did not deny it, nor could they deny that they had done as before stated. . . . It was therefore ordered by the mayor and aldermen that the said nets should be burned at the cross in Cheap, and the said fishermen committed to prison, until they should have paid a fine. . . . And they were accordingly delivered to the sheriff . . . and taken to Newgate.

Afterward, on [19 May], they were brought to the guildhall, before the mayor and aldermen, and by special favor and for charity’s sake, seeing that they were but poor men, the fines were remitted to them for the present, on the understanding that they should behave themselves well for the future, and no longer presume to fish with such nets.

Ordinance That Brewers Shall Not Waste the Water of the Conduit in Cheap, 1345

At a husting of pleas of land, held on [20 July] in the nineteenth year of the reign of King Edward III . . . it was shown by William de Iford, the common serjeant, on behalf of the commonalty, that whereas of old a certain conduit was built in the midst of the city of London, that so the rich and middling persons living there might have water for preparing their food, and the poor have water to drink, the aforesaid water was now so wasted by brewers, and persons keeping brewhouses, and making malt, that in these modern times it will no longer suffice for the rich and middling, or for the poor, to the common loss of the whole community.

And in order to avoid such common loss, it was agreed by the mayor and aldermen, with the assent of the commonalty, that such brewers, or keepers of brewhouses, or makers of malt, shall in future no longer presume to brew or make malt with the water of the conduit. And if anyone shall hereafter presume to make ale with the water of the conduit, or to make malt with the same, he is to lose the tankard or tyne with which he shall have carried the water from the conduit, as well as pay 40d., the first time, for the use of the commonalty; he shall lose the tankard or tyne, and pay half a mark, the second time; and the third time, he is to lose the tankard or tyne, and pay 10s., and further, he is to be committed to prison, to remain there at the discretion of the mayor and aldermen.

It was also agreed at the same husting, that the fishmongers at the stocks, who wash their fish [with that water], shall incur the same penalty.

Royal Order for Cleaning the Streets of the City, and the Banks of the Thames, 1357

The king to the mayor and sheriffs of our city of London, greeting. Considering how the streets, and lanes, and other places in the aforesaid city and its suburbs, in the times of our forefathers and our own, were accustomed to be cleansed from dung, refuse heaps, and other filth, and . . . to be protected from the corruption arising from this waste, from which practice much honor accrued to the said city and its residents; and whereas now, when passing along the water of the Thames, we have beheld dung, and refuse heaps, and other filth accumulated in various places in the said city, upon the bank of the river, and have also perceived the fumes and other abominable stenches arising from these; from the corruption of which, if tolerated, great peril, both to the persons dwelling within the said city and to the nobles and others passing along the said river, will, it is feared, ensue, unless indeed some fitting remedy be speedily provided for the same. . . .

We, wishing to take due precaution against such perils, and to preserve the honor and decency of the same city, in so far as we may, command you to cause both the banks of the said river, and the streets and lanes of the same city, and the suburbs thereof, to be cleansed of dung, refuse heaps, and other filth, without delay, and to keep them clean afterward; further, we command that a public proclamation be made in the aforesaid city and its suburbs, and it to be strictly forbidden on our behalf, that anyone shall, on pain of heavy forfeiture to us, place or cause to be placed dung or other filth . . . in the same. And if you find any persons doing to the contrary, after the proclamation and prohibition are so made, then you are to cause them so to be chastised and punished, that such penalty and chastisement may cause fear and dread unto others and deter them from perpetrating the like. . . .

Royal Order for the Removal of Butchers’ Bridge and the Prevention of the Slaughtering of Beasts at St. Nicholas Shambles, 1369

Edward, by the grace of God etc., to the mayor, recorder, aldermen, and sheriffs of London, greeting. Whereas of late, upon the grievous complaint of various prelates, nobles, and other persons of the aforesaid city, who have houses and buildings in the streets, lanes, and other places, between the Shambles of the butchers of St. Nicholas, near to the mansion of the friars minor of London, and the banks of the Thames near Baynard’s Castle, in the same city, shown by their petition before us and our council in our last Parliament, held at Westminster, we had heard that by reason of the slaughtering of beasts in the said shambles, and the carrying of the entrails and offal of the said beasts through the aforesaid streets, lanes, and places to the said banks of the river, at the place called “Butchers’ Bridge,” where the same entrails and offal are thrown into the water, and the dropping of the blood of such beasts between the said shambles and the waterside, the same running along the middle of the said streets and lanes, grievous corruption and filth have been generated, both in the water and in the aforesaid streets, lanes, and places, and adjacent parts in the said city; so that no one, by reason of such corruption and filth, could hardly venture to abide in his house there: and we . . . had determined, with the assent of all our Parliament, that the said bridge should be pulled down and wholly removed, before [1 August] last past, . . . and did accordingly give you our commands, that . . . you would cause some more fitting place to be ordained outside the said city, where such slaughtering might be done with the least possible nuisance and grievance of the city, . . . but you have not hitherto cared to do anything, in manifest contempt of ourselves, . . . and to the no small damage and grievance of the same prelates, nobles, and people of the city aforesaid, by which we are greatly moved—

We do therefore again command you, as distinctly as we may, and do enjoin, that you will cause some certain place outside the said city to be ordained, where the slaughtering of such beasts, to the least nuisance and grievance of the commonalty of the city aforesaid, may be done, by [15 August] next ensuing, and the bridge aforesaid in the meantime to be pulled down and wholly removed; or else you will explain to us why you have not obeyed our command aforesaid. . . . And this, on pain of paying £100, you must in no manner fail to do. . . .

Questions: What environmental problems and concerns did fourteenth-century Londoners have? How did they respond to these problems? Who had the authority to order changes, and on what grounds? What attitudes and assumptions about the urban environment underlie their actions?

76. Articles of Accusation against Edward II

Edward II (r. 1307–27) alienated many of his barons by his expensive military failures in Scotland, his deference to royal favorites, and his vindictiveness toward magnates who sought to restrain him. A rebellion led by Edward’s estranged wife Isabella of France and marcher lord Roger Mortimer succeeded in capturing and imprisoning the king, and in January 1327 Parliament convened at Westminster to approve an unprecedented proposal for Edward’s deposition. After approving the king’s deposition, parliamentary representatives offered Edward II the choice of abdication in favor of his son Edward or forcible deposition in favor of a new king selected by his enemies; he chose the former option. Thirteen-year-old Edward III was hastily crowned, and by September Edward II had died (probably murdered) in prison. The following articles show how Edward II’s enemies condemned his shortcomings as king and justified his removal to an initially divided Parliament.

Source: trans. G. Burton Adams and H. Morse Stephens, Select Documents of English Constitutional History (New York: Macmillan, 1901), p. 99; revised.

It has been decided that Prince Edward, the eldest son of the king, shall have the government of the realm and shall be crowned king, for the following reasons:

1. First, because the king is incompetent to govern in person. For throughout his reign he has been controlled and governed by others who have given him evil counsel, to his own dishonor and to the destruction of holy Church and of all his people, without his being willing to see or understand what is good or evil or to make amendment, or his being willing to do as was required by the great and wise men of his realm, or to allow amendment to be made.

2. Item, throughout his reign he has not been willing to listen to good counsel nor to adopt it, nor to give himself to the good government of his realm, but he has always given himself up to unseemly works and occupations, neglecting to satisfy the needs of his realm.

3. Item, through the lack of good government he has lost the realm of Scotland and other territories and lordships in Gascony and Ireland which his father left him in peace, and he has lost the friendship of the king of France and of many other great men.

4. Item, by his pride and obstinacy and by evil counsel he has destroyed holy Church and imprisoned some of the persons of holy Church, and brought distress upon others, and he has also put to a shameful death, imprisoned, exiled, and disinherited many great and noble men.

5. Item, wherein he was bound by his oath to do justice to all, he has not willed to do it, for his own profit and his greed and that of the evil councilors who had been about him, nor has he kept the other points of his oath which he made at his coronation, as he was bound to do.

6. Item, he has abandoned his realm, and left it without a ruler, by going out of the realm with notorious enemies, and doing all that he could to ruin his realm and his people, and what is worse, by his cruelty and lack of character, he has shown himself incorrigible without hope of amendment, which things are so notorious that they cannot be denied.

Questions: What are the main charges against Edward? How do these compare with those made against his grandfather (doc. 56)? Judging from this denunciation, how did Edward II’s contemporaries expect a capable king to rule? Why did the magnates and prelates wish to have Edward’s deposition approved by Parliament?

77. Dispute between an Englishman and a Frenchman

After the loss of Normandy in 1204, most English elites gradually lost the familial and territorial ties that had bound them to the continent; a century and a half later, many had come to regard the French as foreigners and to define their own Englishness in part as a rejection of and assertion of superiority to the French. The Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) encouraged nationalistic sentiment among all social classes. This anonymous work from the 1340s is an excellent example of the anti-French propaganda intended to encourage English support for the war in its early stages.

Source: trans. T.B. James and J. Simons, The Poems of Laurence Minot, 1333–1352 (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1989), pp. 97–99.

The Frenchman Speaks

You reproach me with well-dressed hair, pale cheeks, soft speech, and a controlled, civilized gait. If a sense of order controls the hair and insists that it be neatly dressed, a shambling step would be an abandonment of principles. If my face is pale, it is Pallas [Athena, the goddess of wisdom] who spreads the pallor over my features; this complexion does not come from Venus [goddess of love and sex]. If I utter soft sounds, it is because what was at first a harsh sound to the ears makes the words acceptable when softened in the mouth. If I walk with delicate steps, this is because my outward restraint also controls my inner self. . . .

You also charge us with meanness because we show restraint and refuse to be slaves to our gullets and nothing else. What creatures does England rear except cattle? Their bellies are their god and it is to the belly that they [Englishmen] gladly offer sacrifice. The wasteful glutton fills his gullet and stretches his stomach. He swells up and is more beast than man. To provide him with drink the very ponds are planted with crops: from the union of these two different elements nothing is produced. We drink the liquor of the vine: only the lees [dregs from the bottoms of wine barrels] are sold to England. . . .

The Englishman Speaks

I should like to know why the Frenchman presses me to fight and what effrontery prompts you to speak, Frenchman? What menaces lower from your brow? What threats rumble in your chest? What are your lips up to with their smooth utterance? Leave the men alone, let woman strive with woman: a man’s struggle with a woman is unequal. Whatever posture you take, wherever you go, there is always some element to bring you reproach. Should you look at her head while she preens herself with her neat hair, she involves all the other men on some pretext or another. If she turns her head now to one side, now to the other, you will run off thinking she does not fancy you. If the vice of Venus robs your face of its color, your fault is loudly proclaimed by your paleness. If your tongue softens its force so that your palate does not sound too loud, then it is a woman talking through a man’s lips. If your feet are swollen from walking, you hold them in the air, scarce touching the road with the forward foot. If you surrender other parts to be used like a woman, you act like a woman and pretend not to be a man. If it is because a Frenchwoman is a castrated effeminate Frenchman, then, Frenchman, take the name of French hen and the luck that goes with it.

Lest the only claim on Frenchmen is Venus and her ways, blind avarice has curved their grasping fingers. . . . Be convinced by the evidence of a poor man’s table. Bacchus [the god of wine] saves some of the lees for the servants’ table and the poor man’s table is set with poor food. France harvests the chaff from the vine, England the grain [to make beer]. We drink off the liquor, the Frenchman keeps the rest. Since such French depravity stains the soul of the Frenchman, then, Frenchman, silence is best. Shut up!

Here ends a dispute between an Englishman and a Frenchman.

Questions: What stereotypes were associated with the English by the French, and with the French by the English? How might such a piece have encouraged English support for the war against France?

78. Jean Froissart on the Battle of Crécy

Under Edward III (r. 1327–77), England became involved in the Hundred Years’ War, a protracted but intermittent conflict with France, over a range of issues including English claims to lands in France, the succession to the French throne, and Flemish politics. In August 1346 the English army won its first major victory of the conflict when it defeated a significantly larger French force at Crécy in northern France. The story of the battle is told by the great French chronicler Froissart in his long chronicle of the war.

Source: trans. T. Johnes, Froissart’s Chronicles (London, 1803); repr. in F.A. Ogg, A Source Book of Mediaeval History: Documents Illustrative of European Life and Institutions from the German Invasions to the Renaissance (New York: American Book Company, 1908), pp. 428–36; revised.

The king of England, as I have mentioned before, encamped this Friday in the plain [east of the village of Crécy], for he found the country abounding in provisions; but if they should have failed, he had an abundance in the carriages which attended him. The army set about cleaning and repairing their armor; and the king gave a supper that evening to the earls and barons of his army, where they made good cheer. On their taking leave, the king remained alone with the lord of his bedchamber. He retired into his oratory and, falling on his knees before the altar, prayed to God that if he should fight his enemies on the morrow he might come off with honor. About midnight he went to his bed and, rising early the next day, he and the prince of Wales [Edward, the Black Prince] heard mass and took communion. The greater part of his army did the same. . . .

After mass the king ordered his men to arm themselves and assemble on the ground he had chosen beforehand. He had enclosed a large park near a wood, at the rear of his army, in which he placed all his baggage-wagons and horses, and this park had but one entrance. His men-at-arms and archers remained on foot. The king afterward ordered, through his constable and his two marshals, that the army should be divided into three battalions. . . .

The king then mounted a small palfrey, having a white wand in his hand, and, attended by his two marshals on each side of him, he rode through all the ranks, encouraging and entreating the army to guard his honor. He spoke this so gently, and with such a cheerful countenance, that all who had been dejected were immediately comforted by seeing and hearing him.

When he had thus visited all the battalions, it was near ten o’clock. He retired to his own division and ordered them all to eat heartily afterward and drink a glass. They ate and drank at their ease; and, having packed up pots, barrels, etc., in the carts, they returned to their battalions, according to the marshals’ orders, and seated themselves on the ground, placing their helmets and bows before them, so that they might be the fresher when their enemies should arrive.

That same Saturday, the king of France [Philip VI] arose early and heard mass in the monastery of St. Peter’s in Abbeville, where he was lodged. Having ordered his army to do the same, he left that town after sunrise. When he had marched about two leagues from Abbeville and was approaching the enemy, he was advised to form his army in order of battle, and to let those on foot march forward, so that they would not be trampled by the horses. The king then sent off four knights—the lord Moyne of Bastleberg, the lord of Noyers, the lord of Beaujeu, and the lord of Aubigny—who rode so near to the English that they could clearly distinguish their position. The English plainly perceived that they were come to reconnoiter. However, they took no notice of it, but allowed them to return unmolested. When the king of France saw them coming back, he halted his army, and the knights, pushing through the crowds, came near the king, who asked them, “My lords, what news?” They looked at each other, without opening their mouths, for no one chose to speak first. At last the king addressed the lord Moyne, who was attached to the king of Bohemia, and had performed very many gallant deeds, so that he was esteemed one of the most valiant knights in Christendom. The lord Moyne said, “Sir, I will speak, since it pleases you to order me, but with the assistance of my companions. We have advanced far enough to reconnoiter your enemies. Know, then, that they are drawn up in three battalions and are awaiting you. I would advise, for my part (submitting, however, to better counsel), that you halt your army here and quarter them for the night, for before the rear shall come up and the army be properly drawn out, it will be very late. Your men will be tired and in disorder, while they will find your enemies fresh and properly arrayed. On the morrow, you may draw up your army more at your ease and may reconnoiter at leisure to determine where will be most advantageous to begin the attack; for, be assured, they will wait for you.”

The king commanded that it should be so done; and the two marshals rode, one toward the front, and the other to the rear, crying out, “Halt banners, in the name of God and Saint Denis.” Those that were in the front halted, but those behind said they would not halt until they were as far forward as the front rank. When the front perceived the rear pushing on, they pushed forward; and neither the king nor the marshals could stop them, but they marched on without any order until they came in sight of their enemies. As soon as the foremost rank saw them, they fell back at once in great disorder, which alarmed those in the rear, who thought the fighting had begun. There was then space and room enough for them to have passed forward, had they been willing to do so. Some did so, but others remained behind.

All the roads between Abbeville and Crécy were covered with common people, who, when they had come within three leagues of their enemies, drew their swords, crying out, “Kill, kill;” and with them were many great lords who were eager to display their courage. No man who was not present can imagine, or describe truly, the confusion of that day, especially the bad management and disorder of the French, whose troops were beyond number.

Upon seeing their enemies advance, the English, who were drawn up in three divisions and seated on the ground, arose boldly and fell into their ranks. That of the prince was the first to do so, whose archers were formed in the manner of a portcullis, or harrow, and the men-at-arms in the rear. The earls of Northampton and Arundel, who commanded the second division, had posted themselves in good order on his wing to assist and succor the prince if necessary.

You must know that these kings, dukes, earls, barons, and lords of France did not advance in any regular order, but one after the other, or in any way most pleasing to themselves. As soon as the king of France came in sight of the English his blood began to boil, and he cried out to his marshals, “Order the Genoese forward, and begin the battle, in the name of God and Saint Denis.”

There were about fifteen thousand Genoese crossbowmen; but they were quite fatigued, having marched on foot that day six leagues, completely armed, and with their crossbows. They told the constable that they were not in a fit condition to do any great things that day in battle. The earl of Alençon, hearing this, said, “This is what one gets for employing such scoundrels, who fail when there is any need for them.”

During this time a heavy rain fell, accompanied by thunder and a very terrible eclipse of the sun; and before this rain a great flight of crows hovered in the air over all those battalions, making a loud noise. Shortly afterward it cleared up and the sun shone very brightly, but the Frenchmen had the sun in their faces, and the English at their backs.

When the Genoese were somewhat in order they approached the English and set up a loud shout in order to frighten them, but the latter remained quite still and did not seem to hear it. They then set up a second shout and advanced forward a little, but the English did not move. They hooted a third time, advancing with their crossbows presented, and began to shoot. The English archers then advanced one step forward and shot their arrows with such force and quickness that it seemed as if it snowed.

When the Genoese felt these arrows, which pierced their arms, heads, and through their armor, some of them cut the strings of their crossbows, others flung them on the ground, and all turned about and retreated, quite discomfited. The French had a large body of men-at-arms on horseback, richly dressed, to support the Genoese. The king of France, seeing them fall back, cried out, “Kill those scoundrels for me, for they stop up our road without any reason.” You would then have seen the above-mentioned men-at-arms lay about them, killing as many of these runaways as they could.

The English continued shooting as vigorously and quickly as before. Some of their arrows fell among the horsemen, who were sumptuously equipped, and, killing and wounding many, made them caper and fall among the Genoese, so that they were in such confusion they could never rally again. In the English army there were some Cornish and Welshmen on foot who had armed themselves with large knives. These, advancing through the ranks of the men-at-arms and archers, who made way for them, came upon the French when they were in this danger and, falling upon earls, barons, knights and squires, slew many, at which the king of England was afterward much exasperated.