2

2

How Do I Sound?

WITH YOUR goals and dreams firmly in mind, you’re ready to take what I know will be an eye-and ear-opening trip toward your best voice. Let’s start by addressing the questions that I know are at the front of your mind, the very personal questions that every student I meet, beginner or professional, wants answered: What’s really happening in my voice? If it’s already damaged, can it be fixed? And my favorites: On a scale of bad to excellent, how’s my voice? How good is my voice? How far can I go with it—really?

I try not to think in terms of “good” and “bad,” and I’d like you to put those judgments aside too. For one thing, I’ve learned that they’re too subjective to be useful. Over the years, I’ve asked some of the biggest stars the same question: Putting ego aside, do you like the sound of your voice? And I’ve never found one famous singer who bragged about the way he or she sounded. Generally they admit to me that their voices are full of flaws—and luckily, the public hasn’t picked up on them yet. People who aren’t professional speakers or singers often think that once you reach a certain level, you have great confidence, but the truth is, the voice is always a work in progress, with higher levels to achieve. So instead of good and bad, I’d like to shift our orientation to the two primary questions we’ll be working with in this session:

What is actually going on in my body when I make sounds?

What is actually going on in my body when I make sounds?

How does that translate into the qualities I hear in my voice?

How does that translate into the qualities I hear in my voice?

With the diagnostic tests and exercises in this chapter, we’ll get to know where your voice is at this moment. This will be our starting point for your vocal makeover. The idea is not to accentuate the negative but to get an honest sense of what you’re doing, to get a clear picture of your vocal strengths, and to pinpoint your weak spots—so that we can fix them. Don’t worry—in the course of this book, I’ll give you concrete ways to solve every problem we highlight here.

How Your Voice Works

It will help a lot, as we begin, for you to have a basic idea of how your voice works. We all know that to play a violin you have to press down the strings on the neck with one hand and draw a bow over the lower part of the strings with the other. Playing an oboe involves blowing over a vibrating reed into a tube with holes we cover to create different tones. But the voice is often a mystery. For one thing, we can’t really see our vocal apparatus, and there’s no orchestral equivalent of the strange combination-wind-and-string instrument that resides in our throats and uses our whole bodies as a resonating, sound-shaping container. All we know is that we open our mouths and out comes our sound.

The relationships and dynamics that go into making music and words flow effortlessly from our throats are complex and fascinating. But for our purposes right now, you just need to know the bare-bones basics, which will help you visualize what’s going on as you run through the exercises.

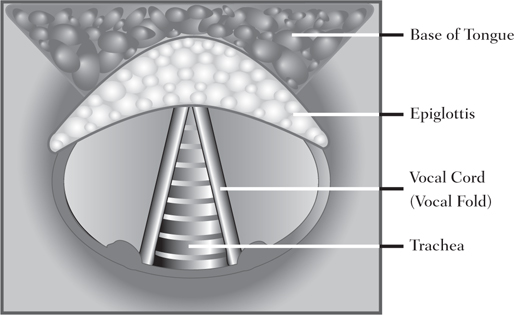

You’ve got a stringed instrument that you blow through. Inside your neck, two passages run side by side. At the front is the one that carries air from the nose and mouth into the lungs. And at the back is the tube that carries food and liquid to the stomach. Resting at the top of the air passage is the cartilage box called the larynx, which contains the vocal cords. The pair of cords responsible for producing the sounds we make are strong, fibered bands of mucous membranes. They move apart and together and vibrate in response to the air we push through them, making this odd little voice box a bit like a violin that you need to blow through to manipulate its pitch, tone, and volume.

You’ve got a stringed instrument that you blow through. Inside your neck, two passages run side by side. At the front is the one that carries air from the nose and mouth into the lungs. And at the back is the tube that carries food and liquid to the stomach. Resting at the top of the air passage is the cartilage box called the larynx, which contains the vocal cords. The pair of cords responsible for producing the sounds we make are strong, fibered bands of mucous membranes. They move apart and together and vibrate in response to the air we push through them, making this odd little voice box a bit like a violin that you need to blow through to manipulate its pitch, tone, and volume.

TOP VIEW OF VOCAL CORDS

The cords have a unique way of vibrating. Small amounts of air build up behind them, and when the pressure of that air becomes greater than the air pressure above the cords, the cords open to release the air, then close. This process happens an astonishing number of times, creating the cords’ vibration. For example, when you sing the note A above middle C, the cords open and close 440 times a second to produce that frequency.

The quality of your voice depends primarily on the way you position the cords and the amount of air you move through them, and great singing or speaking happens when the right amount of air meets the right amount of cord. Remember that phrase because it’s the basis of just about everything we’ll be doing together.

The quality of your voice depends primarily on the way you position the cords and the amount of air you move through them, and great singing or speaking happens when the right amount of air meets the right amount of cord. Remember that phrase because it’s the basis of just about everything we’ll be doing together.

You’ll find that I’ll be explaining many of the sounds you make, particularly problematic sounds that cause you (and your listeners) discomfort, in terms of what’s happening in the crucial relationship between the vocal cords and the air passing through them.

The Spoken You

Whether you’re mainly concerned about your speaking or your singing, I’d like to look first at the speaking voice, because even if we’re professional singers, we spend far more time talking than we do singing. We draw sharp distinctions between what’s spoken and what’s sung, but interestingly, our brains don’t. To the brain, speaking and singing feel almost like the same thing. They use the same body parts, the same muscles, and when you sing, your brain simply thinks you’re speaking but sustaining words an unusually long time and using more pitch variation. Speaking is the jumping-off point for larger leaps into song, so it’s vital to be sure that this foundation is strong.

If you are primarily interested in singing, please don’t skip the tests that focus on how you speak. As I’ve mentioned, one of the greatest dangers to the singing voice isn’t singing but using your voice badly when you talk. By taking time to listen carefully to your speech habits, and correcting any problems, you are protecting your voice against some of its most insidious enemies.

Let a Recording Be Your Second Set of Ears

I strongly recommend that you get out your smartphone and record each of the tests and exercises we do here. Why record? The voice that other people hear doesn’t sound like the one you hear when you speak and sing because you’re feeling the vibrations in your tissues and bones and hearing sounds as they bounce around the “cave” of your body. Your own voice rings and vibrates inside you. But a listener hears only what emerges into the air, and that version of your voice may seem stripped down or flat compared with the richness you feel yourself producing. On top of that, sound traveling away from you actually sounds different from sound traveling toward you. Because of the gap between our inner perception and the listener’s, it helps many students to give themselves an “objective” ear by recording some of the exercises they do.

Take out your phone or other convenient recording device and get ready to make part one of your progress recording. This will be an example of where you began and a powerful motivator along the way, allowing you to look back periodically and see how far you’ve come. It will make your growth visible to you, and especially as you start out, it will be the easiest way for you to listen to your own voice and assess it.

The Overview

Please read the preceding passage aloud into your recorder.

As you read the paragraph, you may have noticed a number of things happening with your voice, if not at the beginning of your reading, then as you got closer to the end. Get out a pencil, and as you play the recording back, look through the following list and mark the items that you think apply to you. Did you

Start strong but peter out by the end, feeling strained?

Start strong but peter out by the end, feeling strained?

Have to clear your throat frequently?

Have to clear your throat frequently?

Sound too soft?

Sound too soft?

Notice that your voice felt too low, and gravelly, especially at the ends of sentences?

Notice that your voice felt too low, and gravelly, especially at the ends of sentences?

Hear your voice breaking in spots?

Hear your voice breaking in spots?

Sound nasal?

Sound nasal?

Sound monotonous?

Sound monotonous?

Sound squeaky?

Sound squeaky?

Sound breathy?

Sound breathy?

Did you hear anything else that sticks out or bothers you?

I believe that people generally have a sense of what they don’t like about their voices, but they may not be able to put it into technical terms. Don’t worry—this is as technical as it gets. Look over the list and notice how many checks you made. It’ll give us a sense of how you hear yourself now and where your problems might be.

Now let’s take a deeper look by doing some specific tests for the most common vocal “flaws”—qualities in the voice that detract from its power by drawing attention to themselves rather than to what’s being said. As you do the tests and exercises, have fun with the interesting sounds that pop up. Some of them may seem a little funny to you, but believe me, I have a specific reason for asking you to make each sound.

It’s All in the Nose

There are a lot of misconceptions about how and why our voices sound nasal. Many people imagine that too much air being expelled is going into the nose, echoing around and giving their voices a nasal quality. And that’s partly right. As you go higher in the range, a certain amount of air is supposed to be directed below the roof of your mouth, and a certain amount is supposed to go above the soft palate into the sinus area. (Anatomy lesson: Put the tip of your tongue right behind your front teeth and run it over the roof of your mouth. The hard section you feel in the front is the hard palate, and the softer area toward your throat is, you guessed it, the soft palate.)

Some nasal sounds come about when a speaker tightens the back of his or her throat, which keeps the air from freely flowing into the mouth. With that escape route from the body blocked, unnatural amounts of air are directed toward the nasal area. That produces the rather harsh, trebly nasal sound of the Nasal Professor. Listen to my demonstration on audio 2 on the website (www.setyourvoicefreebook.com). The sound is blatantly obvious here, but many people are painfully close to it without knowing.

Could that be you? Try this test. Begin to count slowly from one to ten. When you reach the number five, gently pinch your nostrils shut and keep counting. How do you sound on numbers six through ten? Did the sound drastically change?

It might surprise you to learn that there should be no severe change after you pinch your nose. Just listen to how I sound on audio 3. There’s no huge shift when I reach the number six. Why? If you’re speaking correctly, only a tiny amount of air goes into your nose. So when you pinch your nostrils, the amount of air you’re restricting should barely affect the way you sound, though you may hear a slightly blocked sound on the numbers that contain ns—that’s normal. If you noticed a drastic change, it’s a sure indication that you’ve got too much air going toward the nasal area.

The Other Nasal Voice

There’s another very common cause of the “too nasal” voice, and it’s the opposite of what we just saw: too little air in the nose. Think of Sylvester Stallone as Rocky, with a low, blocked nasal sound that was most certainly the result of one too many run-ins with a boxing glove.

Listen to the demonstration on audio 4 on the website. Once again, my examples are extreme because I want you to recognize easily what I’m after. Unless you currently have a severe cold, your voice probably doesn’t sound like this. But toward the light end of this nasal spectrum, you might recognize something of yourself.

It’s entirely possible that you have mild, unwanted nasal tones in your voice and won’t be aware of them until you hear your voice played back to you. So right now, go back to your recordings and listen specifically for the two nasal sounds I’ve demonstrated. If you’re hearing them, you’re not alone. Nasality is common because it’s so easy to send too much or too little air into the nasal passages until your voice is completely aligned.

Once your voice becomes nasal, for whatever reason, it may get stuck in that nasal place. Why? One prominent reason is “sound memory.” Your brain remembers what you sound like every day, and it’s constantly reassessing what the qualities of “you” are. It hears the sounds you make and tries to duplicate them the next time you speak.

Say you spend a couple of weeks with a cold. The brain begins to associate that plugged-up sound with you and subtly prods you to hold on to that sound—even when you can breathe again. The cold ends but your voice stays nasal. Your brain is misguidedly telling you that this is what you sounded like yesterday, so this is what you should sound like today.

Fortunately, you can use the same sound memory to help lead you out of the problem. Practicing new ways of making sounds not only teaches you how to do it—it also tells the brain, repeatedly, this is how I sound. This is the voice I want, and when I get off track, this is the way to get back.

The Sound of Gravel

You may have noticed that as you were reading the text for your progress recording, the quality of your voice varied. Sometimes it felt smooth, and at others the smooth, mellifluous tones seemed to break up into particles that crackled like a creaky old door hinge. I describe this sound as gravelly, and to be sure we’re on the same wavelength as we try to diagnose it, please listen to audio 5 on the website.

You’ll notice that as I read, using my gravelly voice, I seem to fall into a consistent pattern. I start out strong at the beginning of a phrase, as full of fuel and power as a jet at takeoff. But as I go on, the sound seems to peter out and get harsh. This tonality can actually take on a dark, even sinister, edge. If I use it through the entire course of a sentence, it’s about as appealing as the sound of paper being crumpled. It’s problematic, too, because the process of producing it makes the vocal cords red and swollen.

What’s happening here? It’s fairly accurate to compare a voice at the beginning of a sentence with a car that’s just had the gas tank filled. As you begin to read aloud or speak, you take a breath—the fuel of the voice—and the words ride out on a solid cushion of air. At that moment, the vocal cords are wonderfully content, vibrating beautifully and evenly. But just as a car sputters to a stop when it runs out of fuel, when you are speaking and run out of air, the cords continue to vibrate without their air “cushion,” and as they do, they rub together aggressively. If you push on anyway, they become irritated, and the voice creaks to a stop.

Listen to the demonstration once more and imitate me. Close your lips, say mmmmmmm,… and feel vibration in back of your throat. Now read a couple of sentences on your own and see if you notice that same type of vibration as you reach the end of your breaths. Try it one more time, this time holding your hand about a half inch from your mouth. Pay attention to how much air you feel hitting your fingers. If your sentences end in that gravelly sound, you’ll notice that almost no air is reaching your fingers. Read again and try to keep a consistent flow of air hitting the fingers; when the air stops or greatly diminishes—take another breath.

This incorrect use of the voice affects a large percentage of the population. Fortunately, it’s one of the easiest problems to correct. Simple changes in how you breathe, which we’ll cover in the next chapter, will give you almost immediate relief. Many people are reluctant to breathe more. We have a sense of urgency about getting words out, making us press on instead of pausing to refuel. But there’s an acceptable middle ground, somewhere between panting and talking till we’re blue in the face and gasping for air. We’ll learn how and where to take in the right amount of air and what exactly to do with it.

The Breathy Voice: Sexy but Deadly

I always used to laugh when I called my friend Jeff at his office and got his answering machine. He’d gotten his secretary to record a short message in breathy, Marilyn Monroe–like tones, and when she said, “Jeff can’t come to the phone right now,” it was easy to imagine that the reason had something to do with what was going on in the bedroom instead of the boardroom.

I became interested in studying the effects of using the breathy side of the voice in junior high, when a friend and I decided to make a documentary at a religious retreat in the mountains. As I interviewed the monks, I was immediately aware of how calming their light, airy voices were. They spoke so softly that the sound of my camera often seemed to drown them out, but they still somehow commanded attention.

What is it about this kind of speaking that’s so appealing? Maybe it’s the vulnerability it seems to hint at. Perhaps we find it attractive because instead of asserting itself, it tends to invite us in. In more than a few instances, this quality seems useful and positive, and we choose it because we think it’s the best way to convey certain qualities we want other people to sense. But some people end up breathy because of overcompensation. It’s not unusual for a person who’s been told that his or her voice is harsh, irritating, abrasive, or loud to swing far in the other direction and to tone it down with breathiness. The problem is, no matter how you arrive at this way of speaking, it’s incredibly hard on your vocal cords.

Listen to the demonstration of this sound on audio 6. Now try reading a couple of sentences this way yourself. When you speak like this, only a small portion of the vocal cords is vibrating at all. So much air is pushing through them that much of their natural vibration stops. They begin to move out of the way and begrudgingly let too much air pass. The result is something like windburn. The vocal cords get dry, red, and irritated, and their natural lubrication all but disappears. The irritation makes them swell, a condition called edema, and if you don’t step in to give them relief, it’s possible that soon no sound will come out at all.

I’d like you to keep in mind that while you may find a breathy voice inviting, the lover or mystic who’s flirting with laryngitis is less than appealing, and laryngitis is definitely on the menu if you don’t find alternatives to this way of speaking. You think breathy is the only way to sound sexy, approachable, gentle, or romantic? That’s just not the case. A healthy voice that has command of all the sound possibilities will eventually be more than enough to seduce anyone.

Attaaaaaack of the Brassy Voice

What would a band be without its horn section adding bright, concentrated sound? In the mix of vocal qualities, a little bit of brass provides a jolt of energy that can make you memorable. But when your voice is all brass, the effect can be just a wee bit… irritating.

What exactly do I mean by a brassy voice? Say the word brassy. Now say it again, this time holding the aaa sound. When you do that, you’ll probably get a rendition that has too much extra buzz. Listen to audio 7 on the website and you’ll hear my over-the-top demonstration of various brassy renditions that sound as though I’m hitting a buzzer when I speak. It’s the sound of a bratty kid or a person who can’t, or won’t, soften her sharp edges.

Brassiness happens when your vocal cords are vibrating fully, like the long strings of a piano. Under the right circumstances, that kind of vibration is the basis of a wonderfully resonant tone. Here, however, there’s not enough airflow to produce great resonance. Instead, your body is actually swallowing up the richness before it can come out.

Remember that there are two passages in your throat, one for air and one for food. When you swallow, one function of the larynx, the house of the vocal cords, is to rise, blocking the air passage so no food or liquid gets in your lungs. You can feel this happening if you put your finger on your chin and slide it backward down your throat until you get to the first bump, your Adam’s apple, which is the front part of the larynx. As you swallow, you’ll feel how it goes way above your finger and then back down. At certain times that “swallow, rise, block-the-throat” motion may be a lifesaver—none of us needs food in the windpipe—but when it happens at the wrong time, it cuts off the air passage and stops the production of great vocal sounds.

To find out if your larynx is rising too high, closing up your throat as you speak, try this. Put your index finger back on your Adam’s apple and read the next few sentences aloud. If the larynx jumps substantially above your finger, as it did when you swallowed, that’s too much movement. The larynx is allowed to move up and down between one-quarter and one-third of an inch as you speak, but any more than that places it in a blocking position.

A high larynx is one of the most common problems affecting speakers and singers, but it’s very simple to get the larynx to its proper position with a series of low-larynx exercises. Let me give you a quick hint here of how easy it is to lower your larynx. Listen to audio 8 on the website. The exercise I’m doing here is specifically designed to move your larynx down. As you imitate my sounds, you should feel your Adam’s apple move to a very low spot in your neck. You’ll be happy to know that the larynx is one of the parts of the body that has great sense memory. Once it gets used to sitting in its normal position, it stays there, even if you aren’t doing an exercise. And with the larynx in its normal, healthy speaking position, you will have effectively turned down the excess brassiness of your voice.

The Husky Voice

Less common than the qualities we’ve seen so far, but an occasional standout in the sea of troublesome vocal traits, is the guttural, raspy, Louis Armstrong sound. My demonstration of this sound is on audio 9 on the website. Grating and often unpleasant, it’s produced when the forces that produced the breathy voice and the ones that produced the brassy voice come together. For this sound to happen, the larynx must rise and partially block the windpipe. At the same time, a tremendous amount of air must be pushed through the vocal cords, forcing them apart so that only their outer edges vibrate. As the excess air pushes through, it combines with phlegm and natural moisture and begins to rumble. This sound is a cord killer. When I demonstrate it for even a few seconds, I feel my throat start to hurt and the cords beginning to dry and swell.

But if it’s your habitual sound, you probably don’t even notice the constriction of your throat or the irritation in the cords. It’s a sure bet, though, that you have a little trouble with hoarseness and occasionally lose your voice. If you hear even small traces of this quality in your voice when you listen to yourself, pay close attention to the sections of this book that deal with breathing, larynx work, and reducing phlegm. All of them will move you out of the vocal danger zone that the husky voice places you in.

Too High? Too Low?

It’s always disconcerting to hear someone speaking a range that doesn’t seem to suit the person—like a David Beckham with a high, childlike voice, for example. Our voices naturally want to fall into a particular pitch range as we speak, but often we’ve developed bad habits, or made unconscious choices, that force our voices into uncomfortable areas of the range, the equivalent of a shoe that doesn’t really fit.

How do you know if you’re too high or too low? First try this: Go to the lowest note you can comfortably hit with a certain amount of volume (your rendition of “Ol’ Man River” might help you get there). From that place, say “Hello,” holding out the o sound. If you’re doing it right, you should hear and feel a low, rumbling voice coming out of your mouth. Recognize it? If this is anywhere near the normal sound and placement of your speaking voice, it’s way too low. I’ll show you how to reset it in a more comfortable, and natural, range.

Now listen to audio 10. You’ll hear me repeating my first low hello and talking you through the following exercise. Put your four fingers (no thumb) on your stomach right below your sternum, the area at the top of the stomach where your ribs come together. As you say that drawn-out “hellooooooo,” press with your fingers in a rapid, pulsating motion that pushes your stomach in. As you do this, your voice should jump from the low pitch to a note that is much higher. Concentrate on the higher pitch and try to let go of the low one altogether.

Try again, and this time, when you get to the higher pitch, change the words. Say “Helloooooo. How are you todaaaaaaaaay.” Keep pushing your stomach in with that pulsating rhythm. The pitch you are now hovering around is closer to the range where you should normally be speaking.

This is by no means a foolproof test but rather a way to give you a fast hint at a better pitch for your voice. You won’t really have to worry about actively finding the right pitch area because, as we do the vocal warm-ups I’ll show you in chapter 4, the right pitch will find you. Your voice will effortlessly fall into the correct pitch range for speaking.

At this point, don’t worry about whether you’re a soprano (the highest female voice) or a bass (the lowest male voice). If you’re curious, I’ll help you categorize your voice once you’ve worked on putting it in its most natural spot. For now, though, just try the exercise and see if you find your voice in an unaccustomed, but perhaps intriguing, new place.

Getting a Fix on Your Singing Voice

Singers, I know this is what you’ve been waiting for. Speakers, I’d really like you to stay with me and give this a try. Follow me through these exercises and you’ll gain a wealth of vocal characteristics that will immediately and forever enrich your speaking voice. It’s important for all of us to stop drawing a line between speaking and singing. Remember, your brain thinks they’re almost the same thing, and I hope you’ll regard the work we’ll be doing next as sound exercises. They’re simply vocal exercises attached to musical notes, and they’ll help you, as nothing else can, to make your voice its most resonant and beautiful.

In a moment, when you listen to audio 11 (male) or audio 12 (female) on the website, please understand that I’m using this exercise to give you detailed information about where your voice is right now. Every student I work with starts here, and students often ask me why I choose such a difficult first test. The answer is that I hate wasting time. I want to cut right to the heart of the situation, with sounds that bring all good and bad immediately to the fore. The reason I’ve chosen the ah sound is that it opens up the back part of your throat and sends a lot of air to the vocal cords. It takes great skill to control that much air, and as you try to do it, you’ll get a quick, vivid picture of the pluses and minuses in your voice.

When people come to my seminars and lectures, they’re amazed to find that I can diagnose the full potential of their voices with just one exercise. I can tell people what type of voice lessons they’ve had, what kind of techniques they might have studied, whether they smoke, probably what they eat and drink. I’m a well-trained listener, but this exercise is so revealing that it will give detailed information to anyone who’s willing to listen carefully.

Do the exercise on audio 11 (male) or audio 12 (female), record it, and then play it back. As you do, use the following checklist to help yourself listen for the same indicators I do when I’m with a student. I want you to understand what’s going on in my head so we can effectively share the same set of ears. Pay close attention, and take note of the answers to the following questions:

1. What happens in the range you normally speak in, those comfortable notes that feel as though they vibrate mostly in your chest? What is that comfortable voice like? Is it thick or kind of reedy or whispery? Does it have a nice resonance?

2. What happens as you approach the top of this range? Is there a buildup of pressure as you go higher? Do your throat muscles feel tight, as though you’re doing the equivalent of lifting weights?

Are you straining hard?

Are you getting louder, and shouting as you move higher? (Notice that in the demonstration, I am just moving up and down the range, not changing volume at all.)

3. As you try to go higher, what happens?

Does your voice seem to get thinner and less powerful?

Does your voice crack, or yodel and flip into an airy nothingness?

Does your sound change so dramatically that you sound like a completely different person?

Each of these questions will help you judge where your singing voice is today. If going higher was no problem for you, and you found that you could do it easily, with no (or small) breaks—great. If you sounded like Tarzan falling off a jungle vine—no problem. I’ll show you how to climb back on and swing.

Don’t let this test frustrate you. Use it as I do, to identify the weak spots. I promise not to expose anything that I can’t easily fix with a little bit of practice and commitment.

Freeing Yourself from the Bad Habits

I hope you’ll keep in mind that at every point you heard a sound you didn’t like, or noticed a flaw, you were actually listening to the sound of a bad habit. Our work together will be a process of making you conscious of the bad habits and directing the body toward a more natural means of expression. Step-by-step we will exchange bad for good: pressure for ease, tension for relaxation, constriction for freedom, and pain for pleasure. Without the obstacles we’ve inadvertently set in the way of the voice’s free flow, its real beauty can surface. The careful listening you’ve just done is a crucial foundation. Now follow along with me, and have a bit of faith. Your voice already sounds better.