3

3

Breathing

THE MAGIC that I work with voices is built on a fundamental rhythm: the movements of the body as you inhale and exhale. Breathing smoothly and deeply works wonders for the body in general. It gives you more energy. It can center and calm your mind. And it will give your voice power and consistency. Once you learn to breathe as calmly and steadily as a child does, you are on your way to fabulous vocal reaches.

So how’s your breathing? Let’s find out right now.

Stand comfortably in front of a mirror and take a deep breath, inhaling through your nose. Fill up your lungs as completely as you can, then blow the air slowly out through your mouth. Take a mental snapshot of what you just saw and felt. What parts of your body were involved? What moved? How did it feel? The details are important here, so really focus on what you’re doing. Breathe in through your nose, fill up your lungs, breathe out. We’re all born knowing how to do this perfectly. But how easily we forget. To the smooth in-and-out movement of natural breathing, we add bells and whistles, superchargers, and huge dollops of effort.

When I stand in front of a group of new students and ask them to take a deep breath, giving them the same instructions I just gave you, amazing things happen. Chests puff up, and all over the room, shoulders pop up like bread from a toaster. Here and there, I’ll see an occasional Buddha belly, from a person who’s been told in the past that deep breathing involves filling up the lower abdomen. There’s a strong sense of people actively pushing their bodies open to make space for more air, as though they’re pulling on the sides of an empty balloon and holding them apart to make room for more breath.

The exhale is sometimes very forceful, another powerful push, as though they’re trying to give birth to a beautiful sound by putting all their strength behind it. You can sometimes see the tension in their faces as they contract their stomach muscles to propel the air out of their lungs.

Does this picture look or feel familiar? Did you notice the toaster effect with your shoulders when you inhaled? Did you feel yourself actively pushing your ribs apart and trying to make your chest larger? How was the exhale? Did you tighten your stomach to get the last bit of air out and keep the stream strong? Did your stomach tense and remain locked while the air was trying to get out of your mouth?

The funny thing is, in breathing there’s no extra credit for putting all your will, effort, and muscle into getting it right. In fact, all those elements get in the way. Forcing and pushing your breath is a bit like tap dancing on a five-mile hike. You expend a lot of energy, feel like you’re giving it your all—and wind up way too exhausted to finish your speech or song with the same power you had when you started. Breathing with physical tension is exhausting, and it wreaks havoc on your stamina. But solid, effective diaphragmatic breathing is just the opposite. It isn’t flashy. When you’re doing it, air glides easily in and out. And you can do it forever.

In this chapter I’d like to show you how to strip off the layers of unconscious habits and misguided techniques that stand between you and perfect diaphragmatic breathing, that sheathed-in-mystery process that so many teachers have made complicated over the years. Breathing, as they say in California, is a Zen thing to experience: we have to allow it to happen instead of forcing it. We’re meant to float through this kind of breathing instead of turning it into a grueling, athletic butterfly stroke. By paying attention to when it gets difficult, or when it seems to take special effort, you’ll be able to relax and let the breathing be steady, smooth, and even, the perfect foundation for beautiful speaking and singing.

Natural Breathing

To understand how tension and effort get in the way of correct breathing, you need to know a little about what’s happening inside your body. We’re lucky enough not to have to think about how to make all the parts mesh when we inhale and exhale, but bringing some consciousness into this automatic process will help you step in and make the adjustments you need.

In a nutshell, this is what the essential breathing equipment looks like and how it works: Your lungs rest on your diaphragm, a large muscular sheet that separates the chest cavity from the abdomen. The diaphragm is attached to your spinal column, lower ribs, and breastbone. It naturally arches upward, but when you inhale, it contracts, moving down an inch or two. That little movement sounds insignificant, but it powers the breathing process. It not only gives the lungs more room to expand; it also changes the pressure within the lungs. Imagine that the lungs are a container with a false bottom. When the diaphragm drops, the “false bottom” falls out and air rushes in to fill the vacuum. When the diaphragm relaxes and begins to rise, the air in the lungs becomes more compressed in its smaller space, and it rushes out.

If the lungs are allowed to hang freely in the chest, and if the diaphragm is allowed to drop and rise, you’ll be breathing like a baby, fully and naturally. That’s the goal.

Now you try it. The instructions that follow are aimed at removing the obstructions that many of us allow to get in the way of deep and easy breathing. I’ll stop to explain each basic step of the process, so you’ll be aware of any “extras” you’re unconsciously adding.

Step One: Good Posture

To begin, we’ll need to create an unobstructed pathway for the inhaled air to travel to the lungs. First, stand up straight, with your feet shoulder width apart. Roll your head around to ease any tension in your neck, then hold your head level, with your chin parallel to the ground, not tipped up or down. Let your shoulder blades slide toward the center of your back so that they’re back and down. If you do this, your chest will be open instead of collapsed, which is just what we want.

Slumping, or even rounding your shoulders forward slightly, partly collapses the upper rib cage and keeps the muscles between the ribs from being able to expand to accommodate the lungs as they fill with air. What we’re looking for is the physical ease that comes from good alignment.

Now bend your knees slightly—just relax and unlock them—and tuck your pelvis under. This slight adjustment helps ensure that the diaphragm can function at maximum capacity. You could think of these movements as taking the kinks out of a garden hose so water can flow out easily. You’re creating an open pathway for the movement of air.

Sure, it’s possible to keep talking or singing if you slump, but it takes a lot more effort than you’re probably aware of. If you’d like a vivid demonstration of what happens to the voice when the rib cage is obstructing air, try this:

Sit with your chest in proper alignment, with back straight and shoulders down. Begin to count aloud slowly to ten, and as you count, round your shoulders and move them toward your knees, as if you were doing a sit-up. Move slowly. You’ll notice that as you get farther and farther down, your voice will begin to close, finally reduced to a squelched wisp of sound. Try to take a deep breath in this position and you’ll feel the air physically blocked. Slight slumping and slouching won’t constrict your voice this much—but they definitely put a pinch on the pipes.

Paying attention to alignment will help you eliminate much of the muscle tension that impedes good singing and speaking. I’m impressed by the ideas developed by movement specialists like those practicing the Alexander Technique, and I think they have definite applications for the work we’re doing here. Alexander Technique experts believe that our bodies were designed to move and perform easily. Watch a healthy toddler in action and you will see an erect spine, free joints, and a large head balancing effortlessly on a small neck. Our natural posture is incredible. But without knowing it, we put unwanted pressure on the body, exerting more force than we need for even the simplest act—standing, sitting, or, I would add, singing. Paying attention to the alignment of the head and the spine can help correct the body’s overall coordination and bring us back into balance. So can being aware of how much force we’re putting into simple actions like lifting a book, opening a jar—or breathing. Balance, once we find it, is essentially effortless, and so is the flow of air into and out of our bodies. Discovering a way of standing that opens and lines you up may seem incidental to singing and speaking, but it frees space and energy for producing beautiful sounds.

Step Two: Inhale

Now I’d like you to put your hand on your stomach, with your middle finger on your belly button. All the action that follows should take place in the space between the base of your ribs and just below your belly button. Keeping your shoulders in that beautiful, open position, back and down, imagine that your stomach is a balloon, and as you inhale, let it fill with air. Concentrate on filling this “balloon” only. And when it’s full, blow the air gently out through your mouth.

Try this for a few minutes, remembering that you just want to blow up the balloon without lifting your shoulders or puffing up your chest. How does this feel? Did you find that it was the opposite of what you usually do? Raising your chest and shoulders as you inhale is called accessory breathing, and it’s the surest way to get the least amount of air into the body with the least amount of control. Often, people not only pull their shoulders and chest up as they inhale, but they also feel they should pull in their stomachs. That combination—I think of it as the Hercules breath, because when you do it, you take on the strained look of a guy in the gym lifting heavy weights—keeps all of the movement in the upper part of the body and results in very shallow breathing. Both of these styles of breathing, of course, can be so habitual that they feel completely natural.

If you’re in the habit of dramatically involving your chest and shoulders in your breathing, you’re only partially filling your lungs, and if you pull in your stomach as you do that, your diaphragm has no chance to drop. The quieter, much more subtle way of breathing we’re using here may make you feel like nothing’s happening, but rest assured—subtle is fine.

Diaphragmatic breathing is supposed to be completely relaxing to the body. But on occasion, in the early stages of learning, people can create all kinds of pressure and muscle tension. A few students, for example, say they feel a bit of tension in their stomach or lower back as they inhale. Some have even mentioned that the pain made diaphragmatic breathing an unpleasant experience. This kind of discomfort is not too common, but when it occurs, it’s usually because the student is using the muscles of the stomach improperly.

As you expand the “balloon,” you’re not helping if you apply huge amounts of physical and mental force to push your stomach muscles out and distend your belly. All that pushing can cause you to tighten up, and with enough pushing, you’ll feel like a bomb ready to explode. It may be that you’re trying to fill your lungs too much, thinking that you have to cram every available space with air. It’s a bit like trying to top off the tank at the gas station. It doesn’t make sense, as the lungs will naturally let you know when they’re filled to capacity. Going for unnatural expansion can put huge amounts of pressure on your back and even show up as pain there or in other parts of the body. Stop doing this, and see what happens as you consciously let your abdominal muscles relax while you fill your body with air.

Don’t feel alarmed if you see only a small movement of your stomach when you quit pushing breath in and just let it flow. Many people experience only a small expansion in the front of their bodies as they inhale this way—but they feel their lower back area expand far more, because the diaphragm extends from the front of the body to the back, and its full motion affects the whole core of the body. You can detect the movement at the back of your body by putting your hands just above your waist on your back as you inhale.

When I worked with the actor and director Angelina Jolie, I couldn’t see her stomach come that far forward when she breathed in, so I asked her to focus on filling up the lower part of her back area, as if air were going in there. That worked for her. Then, when she felt comfortable with that placement, we were able to shift more of the movement to the front of her body and she was able to let her stomach expand forward more.

In a very short time, your breathing should be free of chest and shoulder action, and you ought to be able to inhale without stomach tension. Don’t worry if you get a little light-headed at first. People tell me that they sometimes feel a tiny bit dizzy as they begin to learn diaphragmatic breathing. That’s because you’re bringing more air into your system than you’re used to, pushing more air out than before, and possibly hyperventilating. This will pass—and your body will appreciate all the life-giving oxygen you’re feeding it.

Step Three: Focus on the Exhale

This is supposed to be the easy part, the release. As we exhale, the body is designed to allow the stomach to fall easily back to its normal position. It doesn’t take muscle to exhale, just relaxation. But about 85 percent of the singers I work with, and many of the speakers, feel they have to try hard to push the air out. For them, exhaling is more like wringing the air out of their bodies, or straining to give birth, than stepping out of the way as the breath whooshes smoothly out of their mouths.

When we exhale, many of us use force. We tighten. We make it a hundred times harder than it’s supposed to be, thinking, mistakenly, that to get the volume we want, and to hit the high notes, the best thing to do is to fire our voices out a cannon. We all know how forcefully we can make air leave our bodies because we’ve all coughed or sneezed. When our body tries to clear its air passages of obstructions, we automatically tighten the group of muscles located at the top part of the stomach area in the center of the chest where the ribs come together. Tensing this spot can create pressure strong enough to expel a foreign object from the body with more than ten times the force of a normal exhalation. It’s very similar to what you might feel when you strain to force a bowel movement. It wreaks havoc on the body, and the reason we’re discussing it here is this: Tensing these muscles blocks your access to the full use of your voice. When people have trouble with my technique, this tension is the cause about half the time.

Feel it yourself by placing your index and middle finger on the area I just described. In short, strong bursts, say “Go! Go! Go!” Do you feel the muscles under your fingers tighten and lock up when you shoot out that syllable? What you’re doing, as you tighten, is cutting off the flow of air from your lungs.

Why do we do it? Lots of reasons. Many, many untrained singers tighten up the higher they try to go in the range because they equate high pitches with difficulty. As the singer moves up the scale, the brain and body go into what I call weight lifter mode. Believing that will, force, and effort will get them to the top, these singers push harder and harder as they go. And many people don’t realize that’s what they’re doing.

In class one day, I asked my student Kevin to try some exercises. Kevin is a strong, muscular guy whose physique could come only from hours of pumping iron. I demonstrated some sounds, getting higher and higher, and as he followed me, I could see that he was creating huge amounts of tension in his body. When I put my hand on his stomach, I could feel the muscles locking up. It was impossible to miss the additional tension in his face and neck. But he did hit the high notes, and he was all smiles when he got there.

When I told him that I would show him a way to get to the same places without so much pressure and tension, he was confused. “What pressure?” he said. “There was no pressure.” The other students burst out laughing, not quite believing that he could tense up so dramatically and not know it. I explained that when you get used to stomach spasms as you breathe, and experience other tensions in your neck and throat, those feelings become the norm. The strain is immediately apparent to others, but it may be invisible to you. Amazing, isn’t it, how much we learn to ignore this kind of pain.

The fact that he could get the notes out made Kevin’s brain think that he was fine. He hit the pitch he was aiming for, and despite what the effort was costing him, he thought he’d achieved his goal. Because he was strong and used to thinking “no pain, no gain,” his tolerance for physical discomfort was a lot higher than many people’s. So even though we all saw his eyes bulging and his stomach rippling, he didn’t perceive a problem.

Like many of us, he was telling himself: “Singing is work! I’m really high, I’m really loud, I’m calling on my body to do incredible things—and of course there’s going to be tension. That’s what it takes.”

There’s just one problem with that line of thinking: It’s baloney. There’s no connection at all between the strain of power lifting and what’s required for great speaking and singing. The more forceful the stream of air coming at the vocal cords, the harder it is for them to regulate the sounds they produce. Power, range, and consistency depend on smooth, even airflow, not bursts of supercharged breath.

Making the Exhale Easy

So how do we get from rigid to rag doll on the exhalation? A little awareness will go a long way. As you exhale, keep your hand resting on your stomach, and be conscious of when your muscles tighten. You can massage your muscles softly as you exhale to remind them to relax. And if need be, as you’re learning, you can also help your stomach in by pushing gently with your hand, which creates less pressure than using your abdominal muscles. Remember, the goal is not to pull anything in. Just let your stomach fall to its neutral position.

There’s no need to try to push every last bit of air out. There is always air in your lungs (unless one of them is punctured); when all the breathing muscles are relaxed between breaths, the lungs still contain about 40 percent of the volume of air they did when they were completely full. If you forcefully exhale as much as possible, you’ll still have 20 percent of the air left. Take a breath and then blow out all the air in your lungs until you feel they’re empty. When the stream of air stops, blow again. You’ll notice that you still have more air. It’s very difficult to get to empty, so it’s not worth the massive effort so many of us make.

Deep Doesn’t Mean Slow

Have you noticed that diaphragmatic breathing takes longer than “regular” breathing? That was a trick question. Actually, it doesn’t. Sometimes my beginning students think that in order to get air deep into their lungs, they need to take long, drawn-out breaths. After all, they figure, the air has farther to go. But that idea is a fallacy. Once you stop raising your chest and shoulders, air will rush into the lungs in record time. Remember that when the diaphragm is free to move, its movement changes the air pressure in the lungs, and that shift sucks air into your body.

If you try to take in air very slowly, you’re actually restricting the flow in and most likely inhaling through your mouth. You’ll notice that your lips are partially closed and pursed, or your teeth are close together. You might even hear air get caught where your lips and teeth meet, creating the hiss of air being sucked through a tight opening. This is not diaphragmatic breathing. When you’re doing it correctly, the air flows silently in through the nose and races into your lungs.

Getting It Right

For my client Tony Robbins, concentrated practice was the key to letting go of the need to push on the exhale. Tony has a powerful physical presence, something that’s central to his ability to motivate people to be their best, and he tried to power and muscle his way through his first attempts to learn diaphragmatic breathing. Because he wanted to learn fast, we’d sometimes practice for twenty minutes at a time. He’d stand just the way I’ve told you to, and with his eyes closed and his hand on his stomach, he’d pretend to fill up the balloon in his abdomen. After five or ten minutes, it was no problem to get the air in smoothly. But he kept tightening his stomach to help the breath out of his body.

To counter that tendency, we did several breathing exercises that may help you.

The Slow Leak

Put your hand on your stomach and fill your stomach with air. Now close your teeth, placing your tongue against your bottom teeth, and release the smallest amount of air you can through your teeth. Make a tse sound as you release. Practice until you can make your breath last for thirty seconds or longer. (You can hear me demonstrate this exercise on audio 13 on the website.)

Remember that you are letting the air leak out of your lungs—you’re not pushing or using any muscles. Most of all, you’re not trying to get the last molecule of air out of your body. You’re just watching as a small, steady amount of air leaves your mouth. As I’ll show you later, your vocal cords often don’t need any more air than this for beautiful speech and singing!

Blowing Out Candles

Next, try this: Take a proper inhale with your hand on your stomach. Imagine that you’re facing a cake with a line of candles glowing on top. Imagine that the cake is level with your head, about three or four inches away from your mouth. Now softly blow out the candles one by one, opening your lips to blow, quickly closing them, and opening your lips again to blow out the next. As you do this the first time, notice what’s happening to the stomach-area muscles. Do you feel them contracting each time you blow? Do you feel your stomach pushing out against your hand when you blow? Neither of those is the effect you want.

Try blowing out the line of candles again. This time, feel your stomach move in with little pressure when you blow, then stop. Feel it move in, then stop, with each candle you blow out. It shouldn’t come out again until you take your next breath. (Feel free to inhale when you run out of breath.) Notice the difference between this “stop and start” and the more spasm-like jerks that you feel when you tighten your muscles.

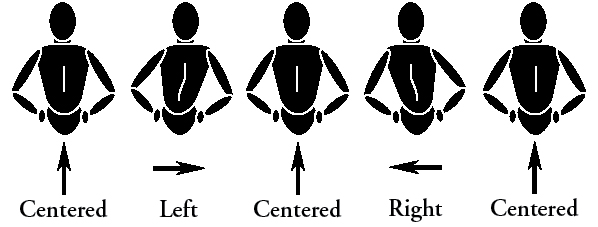

TORSO SWING

The Torso Swing

This exercise, though it’s not for everyone, because it involves a movement the body’s not used to making in its normal range of motion, is a great last resort for unlocking the stomach muscles. To do it, stand up and put your hands on your waist. Now, as the diagram above illustrates, move your rib cage from side to side without moving your hips. In other words, isolate your ribs and keep your body still from the waist down. Keep your shoulders level. I suggest that you try the “slow leak” exercise while doing the torso swing. You’ll find that it’s impossible to swing and clench your breathing muscles at the same time. And once you’ve experienced the feeling of exhaling without tension, you can find your way back to it without the movement. This will be a useful tool later if you find that your stomach tenses up when you do the general exercises.

One More Useful Breathing Trick

Lately, when working with students who are having trouble relaxing into diaphragmatic breathing, I’ve been pulling out what has proved to be a powerful prop: a large book. I find one that’s several inches thick, and I put it on the floor near a wall, asking students to stand straight with their backs against the wall, with the balls of their feet and toes elevated by the book, heels on the floor. Standing in this position tucks your pelvis into correct alignment, which makes it much easier to breathe correctly. My student Aimee was thrilled with the results she got from using this simple technique. She’d been laboring through her diaphragmatic breathing and thought she’d never discover the ease that I’d been promising her. But she felt a shift right away when we tried the posture change, and after a week of practicing on her own, she came in breathing like a diva.

Now I point anyone with difficulties to this easy, accessible tool. Any thick book, or even a rolled-up towel, will do the trick.

Classic Breathing Exercises:

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Students sometimes come to me wondering about breathing exercises they’ve heard of or learned from other teachers. We tend to trust “the experts,” and particularly if an exercise has been around a long time, we assume it must be effective. Sometimes we’re lucky—and sometimes we’ve got a real lemon on our hands.

Take, for example, the belt.

I’ve heard of many instructors who teach diaphragmatic breathing this way: They tell the student to take a deep breath, filling up the whole lower abdomen, which we know doesn’t really have much to do with breathing, and pushing the belly out. At the point of maximum expansion, the teacher takes a long belt and fastens it snugly around the extended stomach. Then the teacher tells the student to exhale, but to keep the belly expanded so that the belt doesn’t drop.

This is somehow supposed to make the breath smoother and stronger, but forcing the belly out, and holding it there, only creates stress and tension, the very factors that get in the way of great breathing.

If this exercise is something you still do, STOP. And if you meet a teacher who advises you to do it, you know what to do. Find a new teacher. The sad truth is that teachers pass on what they have learned. Often no one challenges the master, and one generation after another builds its techniques without questioning or connecting with the underlying physiology. Voice teachers don’t generally go to medical school, and doctors are often too busy to take singing lessons and correct teachers’ misconceptions.

I don’t want to weigh you down with complicated anatomy and technical information, but I do want you to understand the basic physical principles behind what we’re doing. Believe me, when we work with the body instead of against it, the results are remarkable.

I’m certainly not out to discredit techniques just because they’re old, sound weird, or were developed by someone else. Some funny-sounding exercises actually work, and they’re worth holding on to. Case in point: the book on the belly.

Exercising by the Book

Lie on your back with your legs on the seat of a chair. Put a big book on your stomach, right above your belly button. Now inhale deeply into your stomach and exhale, taking care not to use your stomach or chest muscles to “assist” the exhalation. If you’re breathing correctly, you’ll see the book rise as you inhale and sink as you exhale.

Diaphragmatic breathing is easier in this position because when you lie with your legs up, your pelvis tips into good alignment, your back and shoulders are properly set, and you don’t have to wonder if you’re in the right position. Air has easy and full access to your lungs, your lungs are free to expand, and you can experience what good diaphragmatic breathing feels like. What’s the book about? It’s not to apply pressure or to facilitate the breathing—it’s just a great visual aid. You don’t have to wonder if your stomach is moving as it should. All you have to do is look down and see the book rising and falling. The movement’s not huge, but it is easily visible.

The Bends

A final puzzling exercise that’s quite common involves bending over from the waist as you sing an ascending scale. Students are told that if they do this, their sound will somehow improve, and because they feel the exercise does something to help them, sometimes they ask me about it.

Bending over as you sing does a couple of things. It does change the way you breathe out because when you bend until your torso is parallel to the ground, the movement helps push your stomach in to artificially send air out of the lungs. Actually, though, that’s not the only reason the notes might have improved.

The real reason for the change is that as you bend, it’s easy to become afraid that you’ll lose your balance or fall. And when you’re preoccupied with what your body’s doing and how stable your position is, it’s easy to forget that you’re hitting high notes. Bending changes your focus—from “Oh my god, I’m singing higher notes” to “Uh-oh, I might fall.” Lots of students freak out at the thought of trying to go high—until something distracts them.

Is it a real breathing exercise? Not really. But it does serve an interesting purpose for students whose minds get in the way of their singing. As we shape the breath into vocal sounds, I think you’ll keep noticing the same thing: without the interference of tension and pressure (physical or mental), the body knows all about how best to release your true voice into the world. The trick is to get out of the way and let it.

The Tension Trap

The reason it’s so important to drain the strain from breathing is that if you don’t, you’ll be forcing your vocal cords to contend with uneven blasts of air. Imagine trying to play a harmonica, never knowing if a lot of air or a little air was going to come from between your lips. Yes, you might make sounds, even interesting sounds, but it would be hard to know just what was going to happen when you opened your mouth.

When you create tension, you create a tourniquet effect on the air trying to leave the lungs. It’s like putting a cork in a garden hose. Pressure builds, and the air eventually muscles its way through the restricted passage. The air that emerges under these conditions is very concentrated and pressurized, like the water you see spurting from a fire hydrant. And when it hits the vocal cords, it shocks them. The cords react by locking into a set position instead of being able to move. Believe me: for reasons I’ll explain in the next chapter, you don’t want this to happen. Gorgeous singing and speaking require you to be able to let sounds flow out without restriction. It’s the tension blocks that cause problems.

A good way to think about solid breathing is what I think of as the “great waiter” model. If you’ve ever had dinner in a restaurant with four-star service, you’ve probably noticed that your water glass is never empty. You sip, you chat, you eat, and every time you reach for your water glass, it’s full. The magic is that the refills are so unobtrusive they seem to be invisible. It takes practice to allow our breathing to be that easy and invisible as we make sounds, but once you do, you’ve got the best possible foundation for making any sound you choose.

How Long Will It Take?

For a highly motivated student like Tony Robbins, who was focusing on breathing for twenty minutes at a time, it didn’t take long to experience the feeling of just letting the exhale happen. Within a few days, he had found his way from tension to tension-free in his exhalations, and that very small step immediately gave him access to a new freedom in his voice.

It may take you hours, or days, or even weeks to disengage the habits of muscles that are accustomed to locking up as you exhale. But keep working with the exercises and I guarantee that you’ll see progress. I recommend that you stop two or three times a day and think about your breathing for five minutes.

Go for Optimum Results

Diaphragmatic breathing is part of the bedrock of the vocal technique that has made it possible for me to help every kind of person access the vast possibilities of the voice. It’s the tested, proven way of giving the voice the natural fuel it needs for strength, stamina, and experimentation. But the unfortunate truth is that only a handful of singers and speakers have great diaphragmatic breathing. It is possible to make fabulous sounds and still be oblivious to this kind of breathing. I ask you to learn this technique for only one reason: I want you to have the greatest voice available to you. I want you to see, from the beginning, all of what your body is capable of doing, rather than learning to compensate for the things you can’t do.

One notable singer who came late to the notion of diaphragmatic breathing was Luciano Pavarotti, one of the premier tenors of our time. Pavarotti, after singing for many years, was world-famous and starring in the most challenging roles ever written for the tenor voice. Yet he felt that something was missing from his technique. He’d sing like an angel one day, and the next he’d be able to perform but without the spark or the stamina. It bothered him that the quality of his voice would change so much from show to show, and he began to pay close attention to the singing of his favorite vocalists, who seemed able every day to sound as beautiful as the day before. His close observation led him to the conclusion that he had never really mastered the art of breathing. The singers he admired were breathing differently—more deeply and more fluidly.

Pavarotti emulated what he saw, and for the first time in his career, he began to use diaphragmatic breathing. When he did, he said, everything changed for him. He worried less that his voice would be strong one day and feeble the next. He felt he got a much greater level of consistency from his sound, and performing became much more pleasurable.

Taking the time to let the breathing techniques in this chapter become second nature won’t automatically turn you into the next Pavarotti or Barbra Streisand—but it will relax you, focus you, and guarantee that you have all the necessary equipment for producing the full range of sounds available to you. Consistently. Easily. Powerfully.