A Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery

Transnational Music Sampling and Enigma’s “Return to Innocence”

Timothy D. Taylor

Globalization as we currently discuss it and theorize it cannot be conceived of without taking into consideration digital technologies that have sped up the movement of information. It is for this reason that Manuel Castells prefers to label this era both global and informational, not simply one or the other.1 This essay, therefore, takes off from Castells to examine the ways that music moves around the world, and the consequences that this movement can sometimes have, with respect to a specific case of the German band Enigma and their appropriation of a song by aboriginal musicians in Taiwan.

Globalization/“Glocalization”

Much has been made in the last few years of the new globalized, transnational world that we all live in, a world with flows of “technoscapes,” “ideoscapes,” “ethnoscapes,” “mediascapes,” and “finanscapes” that Arjun Appadurai has so influentially labeled and theorized.2 To this list I would add, or tease out, another, an “infoscape,” which to some extent is the atmosphere in which the others exist, made possible by the computer, the Internet, and other digital technologies.3

With the rise of these recent “–scapes,” however, and terms such as transnational or global economy, it has become important to wonder just how new this “new” global economy is, for claims about the new global economy are almost never historically informed. There is a good deal of evidence that, in terms of overseas investment, we aren’t really any more global than we were at the height of the imperial era early in the twentieth century. Doug Henwood has written that in terms of exports as a share of the gross domestic product, the United Kingdom—the biggest imperial power among developed nations—was only a little more globalized in 1992 than in 1913; Mexico exported more than twice as much in 1929 as in 1992; and today, the United Kingdom exports almost twice as much as Japan, which most people think is the biggest exporter. The U.S. economy is more internationalized now than it was at the turn of the century, but it nonetheless exports far less than the United Kingdom and Japan and is in fact closer to Mexico in these terms.4

If we step further back in history we affirm that people—and thus their cultures, and more specifically, for my purposes here, their musics—have always interacted. Historian Jerry H. Bentley asserts that “cross-cultural encounters have been a regular feature of world history since the earliest days of the human species’ existence.”5 Asian, African, and European peoples regularly traveled and interacted, he argues, via trade routes that crossed the Eurasian landmass; religions such as Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam influenced people far from their points of origin.6

Bentley distinguishes three main periods of travel and intercultural exchange, beginning with the Roman and Han empires (he begins in this moment because of the scarcity of historical sources before). He first identifies the era of the ancient silk roads, which he dates at roughly 400 to 200 B.C., as the first major period of intercultural contact. The next major period began around the sixth century; crosscultural exchange was fostered by the foundation of large imperial states such as the Tang, Abbasid, and Carolingian empires and relied on the cooperation of nomadic peoples, who provided transportation links between settled regions. In this period, there was also more frequent sea travel across the Indian Ocean. This second era blended into the third, the last pre-Columbian one, from roughly 1000 to 1350 A.D.; long-distance trade increased dramatically over both sea and land and was marked by the rise of nomadic peoples, namely the Turks and the Mongols, into political power and expansion. The bubonic plague in the later fourteenth century disrupted trade until the fifteenth, leading to a fourth and more studied colonial expansion of European powers.7

Immanuel Wallerstein has written of a period a little later than this, the expansion of European empires after Columbus’s “discovery,” and he coined the term “modern world-system” to describe the establishment of regular contact around most parts of the world. For Wallerstein, modernity itself is this rise of capitalism and world trade that began in the sixteenth century. This expansion, he tells us, wasn’t just a geographic (that is, colonial) expansion but also an economic one, accompanied by demographic growth, increased agricultural productivity, and what he calls the first industrial revolution. It was also, he notes, the period in which regular trade between Europe and the rest of the inhabited world was established.8

At one level, then, while some of the foregoing may resonate with today’s headlines, it’s still old news. Today’s globalization is less something new than a continuation of global processes that have been in place since the late fifteenth century and were themselves preceded by precapitalist forms of crosscultural exchange. To think in binary terms—as if we are now in a moment of “globalization” that renders the past a monolithic moment of “pre-globalization”—doesn’t get us very far.

And yet, of course, some things are different today. Today’s globalization, as people in the so-called developed countries are experiencing it, would not be happening without digital and other technologies; the exchange of information is faster, information travels further, and there’s thus more of it. The main difference, though, isn’t merely the speed of dissemination, or even the seeming glut of forms and signs, but rather the fact that there are more and more signs from elsewhere coming to the developed countries. What we are in the midst of today isn’t simply a globalization in which forms flow everywhere but rather a moment in which forms from elsewhere are coming to the West with increasing frequency; it was this increase in recordings from other places to European and American metropoles that prompted the invention of the term “world music” over a decade ago.9 As Stuart Hall writes, “our lives have been transformed by the struggle of the margins to come into representation.”10 It is thus a bit Euro- and Americentric to think that the world is newly globalized, since Western forms have been globalized for decades, through colonialism, imperialism, and the movement, as Wallerstein writes, from economic cores to peripheries (and the subsequent extraction of materials to the core).

So why is the term “globalization” so frequently used if it describes processes that have been ongoing since the beginning of recorded history? Because it obfuscates, as Doug Henwood, Timothy Brennan, and others have argued.11 The hype surrounding the new global economy covers up to a certain extent the fact that capitalism is as exploitative as it ever was—perhaps more so—and is constantly seeking new people around the world to use as cheap labor, which, according to Wallerstein, has been the impetus behind global expansion for centuries.12 The term also helps preserve an old binary opposition that is increasingly waning, the binary between “global” and “local” that has been much theorized lately.13

Perhaps a better term than globalization is “glocalization,” a word that originated in Japanese business in the late 1980s and was quickly picked up by American business.14 Glocalization emphasizes the extent to which the local and the global are no longer distinct—indeed, never were—but are inextricably intertwined, with one infiltrating and implicating the other. Indeed, it may now be difficult or impossible to speak of one or the other.15 Older forms and problems of globalization continue but are increasingly compromised, challenged, and augmented by this newer phenomenon of glocalization.

Beginnings

Now let me turn to the specific musical case of this article. In May 1988, the cultural ministries of the French and Taiwanese governments brought roughly thirty Taiwanese residents of different ethnic groups to France to give some concerts. These musicians ultimately performed in Switzerland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy for a month, earning a stipend of fifteen dollars per day. Unbeknownst to the musicians, some of their concerts were recorded, and the following year, the Ministère de la Culture et de la Francophonie/Alliance Française issued a CD called Polyphonies vocales des aborigènes de Taïwan that contained some music from these concerts. A Taiwanese ethnomusicologist, Hsu Ying-Chou, says that the musicians signed a contract before the tour and that the Chinese government approved the French recording.16 Pierre Bois, of the Maison des Cultures du Monde, told me that it was his understanding that the musicians did in fact know they were being recorded, and that the Chinese Folk Arts Foundation was in regular contact with the musicians, whom he assumed were paid for an earlier recording.17 (This CD also included music recorded a decade earlier by a Taiwanese ethnomusicologist and was accompanied by liner notes by two Taiwanese ethnomusicologists, one who had made the original field recordings and another who had issued them in Taiwan.)

In the meantime, Michael Cretu, a Rumanian émigré to Germany (also known as “Curly M.C.”) and his band Enigma were busy scoring a colossal international hit with their album MCMXC A.D. This recording came out of nowhere to sell seven million copies worldwide, which made it the most successful German production abroad ever; the single from the album, “Sadeness Pt. 1” (after the Marquis de Sade) became the fastest-selling single in German recording history. MCMXC A.D. went to number one in several European countries, including the U.K., and peaked at number six with a run of 150 weeks on the Billboard 200 chart in the United States. The gimmick (or combination of gimmicks) that proved so salable was Cretu’s mixing of sampled Gregorian chants with dance beats, which resulted in a kind of sped-up New Age litany.18

A few years later, in 1992, Michael Cretu sat in the studio he built with the proceeds from MCMXC A.D. on the island of Ibiza off the coast of Spain. Cretu, in the words of one fan, took “3 years [to] work his way through hundreds of CD’s of native song, sampling, cataloguing and synchronising many sounds before he began his songwriting process.”19 Cretu himself said, “I’m always looking for traces of old and forgotten cultures and I’m listening to hundreds of records and tapes.”20 Stumbling upon Polyphonies vocales des aborigènes de Taïwan, Cretu found what he wanted in the first track, called “Jubilant Drinking Song.” Cretu’s publishing company, Mambo Musik, paid 30,000 francs (about $5,300) to license the vocals from the French Maison des Cultures du Monde; half of this money went to the Chinese Folk Arts Foundation. The resulting single—the most successful single from Enigma’s second album, The Cross of Changes—is called “Return to Innocence,” and it went to number two in Europe, number three in United Kingdom, and number four in the United States. The Cross of Changes went to number two in Europe, number 1 in the United Kingdom, number nine in the United States, and number two in Australia in 1993. Because of Enigma’s earlier success, 1.4 million advance orders were made for this album, which ultimately sold five million copies and was on Billboard’s Top 100 chart for thirty-two straight weeks.

Two years later, Kuo Ying-nan, a seventy-six-year-old betel nut farmer and musician in Taiwan of Ami ethnic ancestry, received a phone call from a friend in Taipei. “‘Hey! Your voice is on the radio!’ And sure enough,” said Kuo, “it was me.”21 “I was really surprised,” he said elsewhere, “but I recognized our voices immediately.”22 Kuo and his wife, Kuo Shin-chu, were two of the musicians who had toured Europe in 1988, and they were also on the earlier recordings collected on the Polyphonies vocales recording.23

Cut to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1996, where the International Olympic Committee was selecting music to showcase at the games their city was to host that summer. They commissioned ex–Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart, a leader in the “world music” genre, and winner of the first Grammy award for that music in 1991, and Hart duly composed “A Call to Nations,” a work that featured many different kinds of drumming as well as Tibetan Buddhist chanting and other sounds, asserting the notion that we’re all one world. Other composers were commissioned, and, relevant to this discussion, previously recorded works were also made official songs of the Olympics. Enigma’s “Return to Innocence” was named one of these. It thus appeared on a collection featuring official Olympics music and was used by CNN and NBC in advertisements for their coverage of the Olympics, though I have been unable to locate this album.24 (Some press reports say that this Olympics exposure is how Kuo learned of the use of his voice.)25 Gill Blake, assistant producer of the project that produced the promotional video for the Olympics, wrote, “We listened to several pieces we felt had something spiritual and timeless about them. It was then purely a matter of making a subjective choice…. In addition, ‘Return to Innocence’ seemed to work in conjunction with the ideas expressed in the video of fair play, peace, unity, etc.”26

On July 1, 1996, just before the beginning of the Olympics, Magic Stone Music, a record label in Taipei, issued a press release that said they were representing the Kuos in a lawsuit against EMI (presumably as the parent company of Virgin, Enigma’s record company), and that they were also producing a new album by them, an album of their traditional music mixed with pop sounds.27 On July 26, 1996, it was announced that the president of the International Olympic Committee, Juan Antonio Samaranch, had decided to send an official thank-you to the Ami couple, following a report to the committee by Wu Ching-Kuo of Taiwan.28 The Kuos’ attorney claimed that the original use of their voices was illegal, and thus all subsequent uses were also.29 Their attorney also said that this was not just an intellectual property case, but that the Kuos’ human rights had been violated: the musicians “think EMI is ignoring the human rights of the Ami people.”30 “Minority peoples around the world have been treated unfairly over and over in this way,” Magic Stone said in their press conference. “In the 17th century, people cheated the aborigines out of their land, but why are the basic rights of aboriginal peoples still being ignored today?”31

At some point (a date has not been mentioned), Enigma was reported to have sent a check for $2,000 (another report said 15,000 francs, which is almost $3,000) to Hsu Tsang Houei, who had made the original field recordings in 1978.32 Professor Hsu deposited the check in an Ami community trust fund. Some reports said that this money was sent to Kuo himself. One account said that Enigma suggested the possibility of further collaborations with Kuo. The Taiwanese government said that the higher figure was paid by the French Maison des Cultures du Monde, which was responding to a letter from Hsu Tsang Houei, and that the money was paid to the Chinese Folk Arts Foundation, which had brought the singers from Taiwan to Europe in the first place. To date, however, the money appears to have remained in the hands of the foundation and has not been paid out to the Kuos or anyone else.33

As far as I can tell, this threatened lawsuit went nowhere for nearly two years. I sent a few faxes to Magic Stone inquiring about its status but received no reply; in the last of these I volunteered my professional services as a musicologist, but still nothing. Finally, in March 1998, two press reports clarified matters. This lawsuit had indeed stalled, because the Kuos’ “representatives” were told by the (presumable) defendants in the suit that it could cost about $1 million to bring suit. Attorneys willing to take on the suit pro bono could not be found until, finally, a Chinese-American intellectual property lawyer agreed to take the case.34

This lawyer, Emil Chang of Oppenheimer, Wolff, and Donnelly in San Jose, California, posted a plea to the Internet newsgroup <alt.music.enigma-dcd-etc> in June 1998 headed “HELP STOP EXPLOITING ABORIGINAL CULTURES! ABORIGINES SUE FOR JUSTICE AND RECOGNITION: JUSTICE FOR THE KUOS!”35 Chang included more explicit information about the suit that demonstrates the chain of ownership in today’s multinational music world, for the suit was filed against a variety of music production and recording companies, including EMI and Sony. The basis of the suit was copyright infringement and “failure to attribute the plaintiffs as the original creators and performers of their work.”

In the middle of the suit, Emil Chang left the firm, and the case was taken over by E. Patrick Ellisen, who told me early in 1999 that the judge was anxious that the case be settled out of court before the scheduled court date of midsummer 1999.36 But mediation in the spring of 1999 failed to produce results, and Ellisen then expected to go to court. The failure of this mediation meant that another lawsuit was filed, against various licensees of EMI, since “Return to Innocence” appeared on many compilation albums as well as in films, television programs, and television advertisements. Ellisen’s office also considered another lawsuit, against EMI in France and Maison des Cultures du Monde, that was not filed.37 Ellisen and his staff faced an uphill battle, for most traditional music is not copyrighted, so it is easy for defendants in such cases to rely on that fact or claim that any usage of it constitutes fair use. For this reason, Robin Lee, director of Taiwan’s Association of Recording Copyright Owners, said that Kuo had no legal case: “The original authors of traditional folk chants have long been dead. And since performers are not authors, they have no copyrights.”38 Lee was wrong, though: it isn’t true that folk music can’t be copyrighted. It has become standard for folk musicians to list the music as traditional, but the “arrangement” of it as copyrighted, as in “All music traditional, arranged by X.” The defendants’ attorneys also claimed that the Kuos knew that they were signing away rights to the concert recordings made in France in 1988, as Pierre Bois of the Maison des Cultures du Monde maintained.

Finally, in June of 1999, the parties reached an out-of-court settlement, most of which is confidential. What is known is that the Kuos will be given written credit on all future releases of the “Return to Innocence” song and would receive a platinum copy of The Cross of Changes album. Additionally, the Kuos would be able to establish a foundation to preserve their group’s culture, particularly its music, an act that Ellisen says was “not to be construed as implying there was any money” in the settlement terms. For its part, Virgin Records America thanked the Kuos “for the important contribution that their arrangement and performance of the vocal chant ‘Jubilant Drinking Song’ made to the song ‘Return to Innocence.’ ”39 The careful use of the word “arrangement” here indicates that Virgin never altered its position on the Kuos’ music—it is an “arrangement,” that is, a version of a work for which they do not hold the copyright.

While the lawsuit was in progress, an established Taiwanese pop band called Xin Baodao Kangle Dui (or New Formosa Band) released an album on which they sing in two local dialects: Minnan Holo, also known as Taiwanese Minnan, and Hakka Kejia.40 The first track is described by a Taiwanese fan as an “Enigma-like song reminding a person most strongly of ‘Return to Innocence.’ The only thing is that it’s done in a mix of Kejia and Taiwanese. It definitely bewildered me the first time I played it.”41 Think of this: a Taiwanese group singing music in local languages in the style of Enigma’s song which had extensively sampled music by an Ami couple singing in their native language. New Formosa Band’s song was compiled and remixed on a later release and advertised as a dance tune with world music rhythms, entitled, in English, “Song for Joyous Gathering.” The band also added a new member on this compilation album: an Aboriginal musician from Taiwan. Bobby Chen, a pop star in Taiwan, has recorded yet another version of this song.42

Twists

That’s the story as clearly and as simply as I can now put it, though there are some interesting twists. Enigma’s fans responded to the claims by the Kuos that they had not been consulted or recompensed, and I am going to turn now to discussing fans’ reactions to this case, for they, too, are no less a part of this “infoscape” surrounding the case of the Kuos and Enigma. The press release mentioned above provoked some angry responses from fans on the Enigma Internet mailing list; a few posters were concerned about the incident, but for the most part Enigma’s fans were angry that someone was, in effect, questioning their hero’s creativity. The most vociferous (and most loudly agreed with) statement was this:

Wow, foreign greed, tis but strange since most greed comes from the States. Now I’ve raved about this before, but I’m sad to say “screw this guy”. He took his cut, and now that his voice is famous people are getting him to cash in on it. There should definately be a statute of limitations on stuff like this, espically if the suits come _after_ the song is a big hit. I shall participate in my very small “one man boycott” (OHHH AHHH :)). And be sure not to help these people profit in any way. But not that it matters to anyone.

Still, why didn’t they sue 3 years ago eh? Ya gotta wonder …

PS Enigma is still the best _where-ever_ and _how-ever_ they get the samples!!!

And so forth. The gist of this and most subsequent posts was that the Kuos had been paid (though, as I indicated, it isn’t clear if they actually received any money) and that they had no right to ask for anything else.

Another post by this same user, slightly mollified by a calm call for fairness, wrote back, saying that

anything he [Kuo] deserves should not have anything to do with Enigma and/or its management. Let the people they bought it from deal with this guy. Also, you have to wonder if it had been some other band and/or the song made little money would anyone care? The only thing left that would make this perfectly _American_ is if this guy claimed some sort of racism or something. eheh :) Seriously though, I think the original party who sold to Enigma should have to be responsible if anyone is going to take the fall. I mean if this original anthro guy made this recording and such then it is kinda public domain stuff. Enigma basically paid the society for their “efforts” and that’s about all that was neccessary. Now if the guy’s original recording had a bunch of dance beats and other vocals then we’d have a problem ;)

This user’s view seems to be that the original recording was of raw material in the public domain, but if the original recording had been refined by the addition of “dance beats and other vocals,” that would indicate that their music had been produced in a studio and thus copyrighted.

After this flurry of responses, lawyer Emil Chang’s later posting, quoted above, generated some rather nasty responses; most Enigma fans (the vast majority of whom subscribe to the mailing list and do not frequent the newsgroup that Chang posted to) were not sympathetic. Most argued that, even though the Kuos contributed something, “Return to Innocence” simply did not exist before Michael Cretu worked his magic. One person wrote, “As so far as ‘Recognition’ goes, an almost 80-year old Taiwanese singer is not credited on each and every copy of Enigma2’s album because Michael Cretu **is** the creator of RTI [“Return to Innocence”]. Period.”

It is clear that Enigma’s fans are heavily invested in their highly romantic perceptions of Michael Cretu’s genius; they view Cretu as a supremely gifted maker of meanings and speak of him in heroic terms. Their denunciations of, and impatience for, the Kuos’ lawsuit makes this clear: they don’t like Cretu’s claim to genius and originality questioned at all. Or, if they admit that Cretu took somebody else’s music, he is described as refining it, turning some raw material into art.43 Here’s one post to the Enigma mailing list during discussions of the Kuos’ lawsuit: “OK, so Cretu probably realized that he could afford (and it would be well worth) a hell of a lot more than $2000 for the recording he made. But look; who else do you know who can take a two thousand dollar recording and make it into a multimillion dollar recording? Do you see that Andy guy who sang part of the chorus complaining? Let’s not forget that even though the dude from Taiwan has a great voice, it was Cretu[’s] creativity that made the real music happen.”

Clearly invoking Romantic ideas of the genius as a person driven to work, and working in isolation, the Enigma FAQ on the Internet describes Cretu working alone in the studio at all hours, sorting through hundreds of CDs to sample: “He is a self-confessed night owl, and also a workaholic, this being seen by the fact that the production phase for The Cross of Changes took 7 months with the computer log of his sound bridge often stating that recording sessions from 10pm to 11am occurred. During this whole period he rarely saw the sun.”44

One of the ways Westerners appropriate other music is to construct the original makers of that appropriated music as anonymous. Anthropologist Sally Price was told by a French art dealer that “If the artist isn’t anonymous, the artist isn’t primitive.”45 Cretu positions Kuo as anonymous and timeless in order to advocate his “return to innocence,” a return to a spiritualized past. But when the makers of the original sounds talk back, Cretu’s originality is called into question.

Kuo and his wife are assumed to be “primitives,” but they’re inconveniently privy to the rest of the world via the various “–scapes” mentioned earlier. At the same time, though, there’s a refusal to recognize this. The Kuos’ music is constructed as “pure,” primitive, and thus infantilized, by Enigma, but by attempting to get credit and remuneration Kuo is behaving too much as a contemporary, worldly person: the subaltern speaks.

Enigma contributes to perceptions of their originality and the “primitive” and/or ancient nature of their music iconographically. The cover art on the single is faux “native” art, the Persian mystic poet Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Din ar-Rumi (1207–1273) is quoted, and more. Enigma also uses a typeface on the cover of the “Return to Innocence” single that looks as though it were made by a manual typewriter, as though Enigma is just a small band who make and sell their own recordings, inviting a degree of credibility with listeners.

One last wrinkle concerns the reticence of Michael Cretu and the people behind Enigma; they claim, through their unnamed manager, that they want to avoid cheap imitations of their music, that is, people who take the samples in an attempt to make music like Enigma’s, and so they rarely disclose where their samples come from, unless, as we saw, they are forced to.46 The keeper of the Enigma FAQ on the Internet, Gavin Stok, met with Enigma’s manager, who works in Mambo Musik based in Munich, and asked him about Enigma’s sampling problems. The manager claimed that license agreements state that they don’t have to credit some samples. It became clear in the course of this interview that Mambo Musik was more worried about other musicians who track down Enigma’s samples in order to make cheap imitations of Enigma. Here are Stok’s words: “Their major concern is of commercial rip-off artists who steal the samples and try to quickly release a song to ‘cash in’ on the popularity of the first single from a new album. Evidence of this was apparent with the release of MCMXC A.D. and Mambo does not want to see it happen again.”47

This is quite an interesting statement. On the one hand, Mambo Musik adheres to the letter of the law, listing sampled musicians only when required to do so; on the other hand, by not crediting other musicians, they are thus making it much harder for people to find those samples. In practices such as these, Mambo is asserting a kind of de facto ownership over Enigma’s samples in these cases. Simon Frith writes that “Samplers have adopted the long established pop rule of thumb about ‘folk music’—a song is in public domain if its author is unlikely to sue you. And so sample records make extensive use of sounds lifted from obscure old tracks and from so-called (far away) ‘world’ music; lifted, it seems, without needing clearance.”48

Without the benefit of an attribution in the liner notes (except in the first European pressing of the album), several people came forward with very different statements about the origins of the sampled music in “Return to Innocence.” Ellie Weinert wrote in Billboard that “the archaicsounding vocals on ‘Return to Innocence’ are not sung in any particular language but represent a sequence of vowels.”49 A later Billboard article referred to the “Indonesian voices” on the album.50 An online review by a Norwegian Enigma fan, keeper of one of the Enigma webpages on the Internet, said that “this track cleverly blends the joik (Lapp chant) with modern rhythms and song structure. The joik is used as the chorus. This track gives me a feeling of pleasure and happiness, and some of the reason is that Enigma has turned to the ancient Nordic musical culture, the Lapps living in the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.”51 (I should point out that the preferred term for “Lapp” is now Saami.) A Finnish Internet user also thought that the music was joik.

But the song is perhaps most frequently heard as Native American. The video that accompanied the song uses images of “Indians in some tropical jungle,” as one fan writes.52 In a class discussion, a student presented this sampled music as Native American, and it has been used as a Native American song on television and in films. One Enigma fan, who claimed to be “part Native American,” heard the song as Native American. And “Return to Innocence” appears in the Jonathan Taylor Thomas/Chevy Chase film Man of the House, a 1995 Disney release about a boy and a man attempting to bond while in the Indian Guides together.

This scramble for attribution provides one example of what this glocalized/informationalized world is bringing. Information may be moving about, but it is not always true or accurate. The Internet is essentially a giant word-of-mouth network, which means that ascertaining “truth” can be problematic, difficult, or impossible. Anyone who paid attention to the Pierre Salinger fiasco (in which the former White House press secretary claimed that a U.S. Navy missile brought down TWA flight 800 over Long Island, based on “proof” obtained on the Internet) knows what I mean. Salinger clearly approached Internet-disseminated texts as journalistic sources (i.e., more conventional texts), only to discover that he had made a rather large mistake.53 For ethnographers and fellow travelers like myself, this is less of a problem, since we are interested less in “truth” than in (re)presentations of truth. But we are also information gatherers, and more than once I have felt stymied by the absence of information—or, just as frequently, the welter of contradictory information—about a particular musician, recording, incident, or what have you.

This is not to say that ours is the Misinformation Age but that the rapid movement of information around the planet does result in mistakes and, sometimes, bizarre forms of relativization. As an example of the latter, take Microsoft’s Encarta encyclopedia CD-ROM. The most recent edition (as of this writing in 1999) was issued in nine versions, each of which was aimed at a particular regional/linguistic market. In the American version, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone; in the Italian version, it was invented by a little-known candlemaker named Antonio Meucci five years earlier. In the American Encarta, Thomas Alva Edison invented the light bulb at the same time as the Briton Joseph Swan, who is credited in the British Encarta as having been first. While such a strategy identifies Microsoft as more of a marketing corporation than one concerned with knowledge, its Encarta staff insists it is attempting to be responsive to different viewpoints. “We’re not changing facts,” says the editor of the U.K. edition, “we’re changing emphasis.”54 But because these changes in “emphasis” can travel beyond their intended audience, others can learn of them, as the spate of publication about this new Encarta illustrates.55

Now let’s move to a discussion of Enigma’s music itself. The song on the original recording of Ami music that Enigma sampled is the first of “Two Weeding and Paddyfield Songs” (called by the couples’ lawyer, Emil Chang, “Jubilant Drinking Song,” and on a later album, “Elders Drinking Song”—the title changes with the use) with the following text:

Friends, we need this hard work, we the people of the land

Let us not despise it!

Friends, we will undertake this difficult task with joy,

So that we may live off the fruits of our labours.

Friends, have no fear of the difficulties, nor the burning sun,

For we are only doing our duty!56

Enigma doesn’t manipulate the Ami song at all, save for the addition of a little reverberation. The fact that Enigma leaves this music largely unchanged points to their usage of it as a kind of artifact, not as something to be ripped apart and scattered throughout their track, as has happened in other cases. The Ami music we hear in “Return to Innocence” is clearly used not as “material” or as “local color” but rather as a largely intact sign of the ethnic/exotic unspoiled by technology or even modernity. This use of identifiably “ethnic” music samples is part of a growing trend in popular musics, and dance musics in particular, even giving rise to a new genre name: “ethnotechno.”57 Some of Enigma’s fans credit Cretu with spawning this new genre with “Return to Innocence.”

Enigma’s song is four minutes sixteen seconds in length, and samples the Kuos’ voices for over two minutes of this time, as shown in table 1. Cretu effectively takes the Kuos’ pentatonic melody and undergirds it with lush, synthesized, diatonic harmonies. The song concludes with a wash in the dominant seventh that takes us to the tonic in minor, which then segues directly into the next track, entitled “I Love You … I’ll Kill You.” The stop-and-start quality of the original Ami music is echoed by the drum track in the Enigma song, an effect that compels the listener’s attention. It also announces the song as one without a practical function, that is, to allow for dancing; you couldn’t dance to it easily with the drum track starting and stopping as it does. Cretu is making another kind of point with this song, moving away from dance and physical pleasure toward something more introspective. The beat isn’t fodder for discotheque music here; it is recoded by Cretu as something primal and timeless, in keeping with the partly “spiritual” orientation of the album, and the band’s style and image more generally.

What Enigma fans seem to like about the song is its homogeneity, its consistency, and its refusal to make the Kuos’ music markedly distinct from the music by Enigma. Enigma experts and fans have commented on the simple formal structure of the song—the Norwegian webpage owner mentioned above calls it their most traditional song—it is a verse-chorus arrangement, with the Ami music serving as the chorus. Some fans like this simplicity, but others find it too simple, too traditional. Other fans believe it to be conservative because the vocals are too intelligible—in other words, too much like what they derisively call “pop music.”

TABLE 1. Enigma: “Return to Innocence,” Lyrics and Events

Time |

Lyrics/Event |

0:00 |

[Kuo Ying-nan sampled voice] |

0:26 |

Love—Devotion |

|

Feeling—Emotion |

0:49 |

Don’t be afraid to be weak |

|

Don’t be too proud to be strong |

|

Just look into your heart, my friend |

|

That will be the return to yourself |

|

The return to innocence. |

1:09 |

[Kuo Ying-nan sampled voice] |

1:29 |

The return to innocence. |

1:31 |

If you want, then start to laugh |

|

If you must, then start to cry |

|

Be yourself, don’t hide |

|

Just believe in destiny. |

1:42 |

Don’t care what people say |

|

Just follow your own way |

|

Don’t give up and use the chance |

|

To return to innocence. |

1:53 |

[Kuo Ying-nan sampled voice] |

2:08 |

[Kuo Hsin-Chu joins sample] |

2:26 |

[drum track stops] |

2:28 |

Spoken: |

|

That’s not the beginning of the end |

|

That’s the return to yourself |

|

The return to innocence. |

2:37 |

[drum track starts] |

2:59 |

[both Kuos sampled] |

3:53 |

[drum track stops] |

3:56 |

Spoken: |

|

That’s the return to innocence. |

4:02 |

[V7, modulation to minor] |

[4:16/0:00] |

[beginning of next track] |

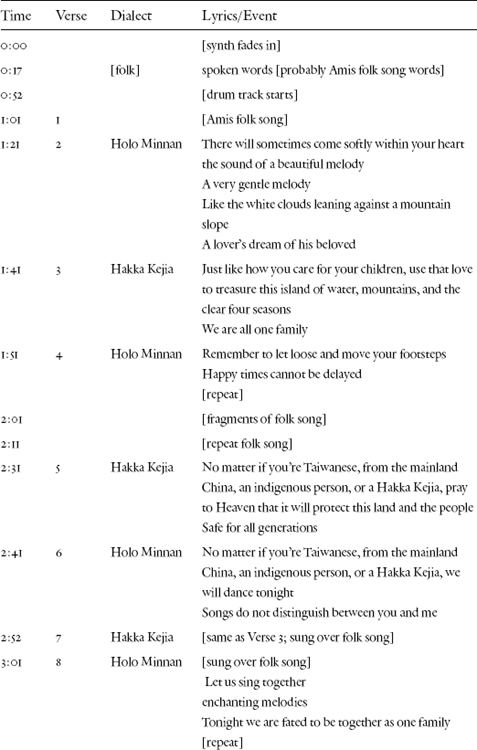

The similar version by the New Formosa Band, however, sounds like pop music. It’s called “Song of Joyous Gathering,” makes use of an Amis folk song from an indigenous group in Taiwan, and is sung or spoken in several dialects, a folk dialect as well as the Holo Minnan and Hakka Kejia dialects. The mention in verse 5 of the Chinese mainland refers to those Chinese who followed Chiang Kai-shek in 1949; the song is generally about setting aside differences. Table 2 includes the lyrics with musical events.

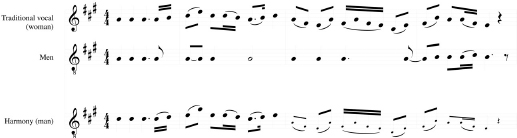

The main similarities with Enigma’s song concern the use of the folk music as a chorus, though the New Formosa Band sings the chorus themselves; it isn’t sampled. The message of unity is made partly in this way, but in other ways as well. The song is almost a study in the possibilities of harmonious, egalitarian combinations and juxtapositions. First, the two singers alternate between the Minnan and Kejia dialects; second, at 3:12 and 5: 03 the folk song is sung first in Minnan and then in the folk dialect, making the earlier idea of juxtaposing languages even more localized; third, the folk song is mixed with the music of verse three; and fourth, the folk song itself is harmonized in thirds for the first two bars (see fig. 1).

The New Formosa Band has recently released a collection that introduces a new member of the band. The track on the collection that they highlight is the one I have just analyzed, but this time in a new guise. It’s a remix of the earlier version, but, despite that, it’s described as a dance tune with world music rhythms, and “world music” is written in English. (There is virtually no English anywhere else, save production and copyright information and descriptions of two other songs, one as “Acid Jazz” and the other as “Techno.”) This remix version cuts a few parts of the original, but the main difference is the addition of a drum track that sounds much more hip hop– influenced than the earlier version.

Fig. 1. New Formosa Band: “Song of Joyous Gathering,” folk melody.

TABLE 2. New Formosa Band: “Song of Joyous Gathering,” Lyrics/Events

The primary significance of the New Formosa Band’s music, for my purposes here, is that it demonstrates the ways in which musics are increasingly caught up in the global flow of sounds, images, ideas, and ideologies made possible by digital technology. Even though this Taiwanese band doesn’t expressly address Enigma’s appropriation of Ami music, they nonetheless critique the blockbuster German band both by asserting a native perspective and working with an indigenous performer, and by scrupulously sharing the spotlight in the song.

Since the onset of this controversy, Difang (Kuo Ying-nan’s Ami name) released the promised recording on Magic Stone in 1998. Circle of Life (the title is in English) shows Kuo on the cover (see fig. 2) and features many traditional songs sung by the Kuos. This album topped the charts in both Taiwan and Japan.

The songs on Circle of Life were mixed in the studio with drum machines and synthesizers and sound much like Enigma’s “Return to Innocence.” But the difference, of course, is that all of this was done with the Kuos’ knowledge, permission, and cooperation. And as a way of further critiquing Enigma’s treatment of them, the penultimate track is a version of the song that Enigma sampled that is far less intrusive. The final track is the original version of their song without any added studio sounds at all.

The Ami music in Circle of Life was recorded in a studio in Taipei. The resulting tapes were then sent to the Belgian musician and producer Dan Lacksman, who had produced the album Deep Forest. The resulting band of the same name is Enigma’s main competitor in the realm of ethnotechno/New Age pop.58 Lacksman also released his own ethnotechno album in 1996, entitled Pangea. He was reportedly recruited via the Internet and has said that Circle of Life represents a crossover between traditional and contemporary music.59 Lacksman’s contribution helps explain the contemporary electronic sound of the album, which may also explain its popularity in Japan, where it was one of the topselling world music albums.

But Lacksman’s presence on Circle of Life also helps illustrate the circle of musical sounds possible under new regimes of glocalization. Lacksman, who credits only one sample on all of Pangea (presumably because that’s the only one the copyright holders were likely to hear), occupies a different structural relationship within the music industry for Circle of Life but at the same time lends his prestige to it, for the words “Deep Forest” (in English) appear on a cardboard slip on the cover.

Fig. 2. Difang: Circle of Life, cover.

That cover was reportedly designed by a Japanese magazine that had sent people to visit Kuo for an interview: “They were so touched by the Ami singers’ songs that they volunteered to do the photography and design work for the record.”60 Kuo thus appears alone on the cover—a true world music star—surrounded by a sea of green grass that situates him and his music in the realm of the “natural,” thus justifying Lacksman’s refinement of this natural musical resource. Photographs inside, and even the picture on the CD itself, continue this theme. The Kuos and the other singers are photographed in their natural habitat, completely exoticized.

This self-exoticization is abetted by the liner notes, which begin in the form of a fable (in fact, the first line is “This is a fable”).61

There was a great eagle, circling in the sky for several generations. Its eyes gazed relentlessly on a flock of people on the ground who had, for many generations, been worshiping the eagle. They night and day, ceaselessly, sung the legends of the eagle. Because of this the eagle was immortal.

But with the passage of time, little by little, the great eagle was no longer able to hear the singing of these ballads. They were being replaced by a catastrophic flood of love stories and wild, violent cryings. The large eagle lost its direction of flight. From then on, the eagle disappeared.

Fortunately, there are still people on the ground who remember those songs, those brave legends—the honesty and purity passed down for generations. Like prophets, they continued to sing and pass them on. But the ignorant have viewed it as a new sound, causing at first apprehension and fear. Later, they blindly followed, plagiarizing. The value of those singing (and passing on) the songs was overlooked.62

The notes then continue to tell Kuo Ying-nan’s story and also relate the story of Enigma’s appropriation of their song, though only obliquely mentioning the lawsuit by referring to “an explosion of international controversy over the authorship and rights of native peoples’ music.”

While it may seem as though the opening of the liner notes perpetuates an old notion of the natural primitive, writing the notes thus has another, clever, aspect, for this style allows Enigma to be accused of plagiarism, a charge that, in the absence of a settlement of the lawsuit, could not be straightforwardly made at the time of the release of the recording. The musical-rhetorical strategy employed by Cretu in “Return to Innocence” to convey feelings of mysticism and timelessness has been used against him to advance the Kuos’ and other Ami viewpoints.

The Enigma and Kuo story is illustrative of older “globalizations” competing with this newer “glocalization,” facilitated mainly by new digital technologies of communication and the dissemination of (mis)information in the “infoscape.”

Enigma’s success with “Return to Innocence” and the entire Cross of Changes album has awakened the music industry to the potential of “indigenous cultures,” to which royalties are almost never paid. This, to recall Wallerstein, is definitely cheap labor. Roger Lee, senior marketing director of Sony Music Taiwan, persuaded Sony’s huge worldwide hit band, Deep Forest, to sample music from the Ami, as they did on their 1995 album Boheme, which won the Grammy award for best world music album in 1995.63 (This album is also popular with Enigma fans, judging by the response on the Enigma Internet mailing list). According to Lee, “This era has revealed the infinite business potential of indigenous culture. We shouldn’t just passively go with the flow of the predominant cultural mechanism. Mainstream needs to be countered by non-mainstream, and any non-mainstream influence may turn out to be tomorrow’s mainstream.”64 The kind of appropriation Lee is advocating has roots, of course, in much older appropriations, as pointed out above, and such a statement points to the kinds of old and continuing problems currently occurring under the rubric of globalization, or, for that matter, postmodernism.

The term globalization can hide old forms of exploitation dressed up in contemporary business language like Roger Lee’s. Capitalism in this global/informational economy is finding new ways of splitting sonic signifiers from their signifieds and from their makers in a process Steven Feld has called “schizophonia.” This newer phenomenon of “glocalization” helps us understand the ways that there may be at the same time new forms of resistance to this process.65 Digitized sounds move to the centers in ways they didn’t before, but, for the first time, the original makers of these musical signs are finding ways of bringing them back home again.

Notes

An earlier version of this essay appears in Timothy D. Taylor, Strange Sounds: Music, Technology and Culture (New York: Routledge, 2001).

1. Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, vol. 1 of The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1996), 66.

2. Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Public Worlds, vol. 1 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

3. This term is derived from Paul Virilio’s idea of the “infosphere,” a kind of information-scape that he believes will assume biological proportions in the near future (Virilio, Open Sky, trans. Julie Rose [London and New York: Verso, 1997]), 84.

4. Doug Henwood, “Post What?” Monthly Review 48 (September 1996), 6–7.

5. Jerry H. Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

6. Ibid., 5.

7. Ibid., 26–27.

8. Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century, Studies in Social Discontinuity (New York: Academic Press, 1974), 102.

9. For more on this point, see Timothy D. Taylor, Global Pop: World Music, World Markets (New York: Routledge, 1997).

10. Stuart Hall, “The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity,” in Culture, Globalization and the World-System, ed. Anthony D. King, Current Debates in Art History, vol. 3 (Binghamton, N.Y.: Department of Art and Art History, State University of New York at Binghamton, 1991), 34.

11. Timothy Brennan, At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now, Convergences: Inventories of the Present (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997).

12. Immanuel Wallerstein, Historical Capitalism (London: Verso, 1983), 39. Some have argued that global expansion has been driven not by the search for cheap labor but new markets (see, most famously, V. I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism: A Popular Outline [New York: International, 1939]).

13. See, for just two examples, Jocelyne Guilbault, “On Redefining the ‘Local’ through World Music,” World of Music 32 (1993): 33–47; and Rob Wilson and Wimal Dissanyake, eds., Global/Local: Cultural Production and the Transnational Imaginary, Asia-Pacific: Culture, Politics, and Society (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996).

14. Roland Robertson, “Globalisation or Glocalisation?” Journal of International Communication 1 (1994): 33. See also Roland Robertson, “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity,” in Global Modernities, ed. Mike Featherstone et al., Theory, Culture and Society (London and Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage, 1995). Virilio, Open Sky, also uses the term. For just two examples of the term in business discourse, see Christopher Conte, “A Special News Report on People and Their Jobs in Offices, Fields and Factories,” Wall Street Journal, May 21, 1991, sec. A, p. 1; and Martha H. Peak, “Developing an International Style of Management,” Management Review, February 1991, 32–35; a recent scholarly article that considers the term is Marwan M. Kraidy, “The Global, the Local, and the Hybrid: A Native Ethnography of Glocalization,” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 16 (December 1999): 456–76. For other uses of the term, as well as alternatives to it, see Philip Hayward, “Cultural Tectonics,” Convergence 6 (spring 2000): 39–47. Lastly, see Timothy D. Taylor, “World Music in Television Ads,” American Music 18 (summer 2000): 162–92, for a discussion of American and European business attitudes toward the global and the local.

15. For a discussion of the false dichotomy of “global” and “local,” see Charles Piot, Remotely Global: Village Modernity in West Africa (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). I would like to thank Louise Meintjes for this reference.

16. “IOC President to Thank Ami Singers,” Free China Journal,<http://ww3.sinanet.com/heartbeat/fcj/0726news/16_E.html>. This URL is no longer active.

17. Pierre Bois, email communication, March 29, 1999. He reiterates this rather defensively in a later email, April 7, 1999.

18. By “New Age” I’m referring to a middle-class rejection of mainstream religions and a turn to other forms of spirituality. See Wouter J. Hanegraaff, New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought, Studies in the History of Religions, vol. 72 (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996); Paul Heelas, The New Age Movement: The Celebration of the Self and the Sacralization of Modernity (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1996); and Deborah Root, “Conquest, Appropriation, and Cultural Difference,” chap. 3 in Cannibal Culture: Art, Appropriation, and the Commodification of Difference (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996). I should note that there has been a good deal of discussion on the Enigma Internet mailing list concerning the New Age category; some liked it, but the majority didn’t.

19. Enigma FAQ, <http://www.spikes.com/enigma/faq/faq5.htm>. All quotations from the Internet appear with their original spelling and punctuation unless otherwise indicated.

20. Enigma Live Chat Event on the Internet, December 13, 1996.

21. Renata Huang, “Golden Oldie,” Far Eastern Economic Review, November 2, 1995, 62.

22. Ashley Esarey, “An Ami Couple Seeks Recognition for Their Music,” <http://www.sinica.edu/tw/tit/special/0996_Innocence.html>. This URL is no longer active.

23. There is also another story that Kuo tells: “Two years ago, my granddaughter brought a tape home and played me the song on the Enigma record. That’s the first time I heard that Enigma had used my voice. I was very surprised and happy. It felt good to have people using my voice, but I was also surprised because I never sang such a song with all those other sounds, I wondered how it was made” (Lifvon Guo [Kuo Ying-nan], interview by Frank Kohler, All Things Considered, National Public Radio, June 11, 1996).

24. “Olympic Music from Taiwan,” <http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/smlpp/enigma.htm>. This URL is no longer active. “Return to Innocence” has appeared on many other compilations, however, including Dance Mix USA, vol. 2, Quality Music 3902, n.d.; Dance Mix USA, vol. 3, Quality Music 6727, 1995; First Generation: 25 Years of Virgin, Virgin 46589, 1998; High on Dance, Quality Music 6741, 1995; Loaded, vol. 1, EMI America 32393, 1995; and Pure Moods, Virgin 42186, 1997.

25. “Ami Sounds Scale Olympian Heights,” <http://www.gio.gov.tw/info/sinorama/8508/508006e1.html>. This URL is no longer active.

26. Ibid.

27. “From Betelnuts to Billboard Hits,” <http://pathfind.com/@@CkDcMAcA0VE9Uaiw/Asiaweek/96/1122/feat5.html>. This URL is no longer active. The new recording, called Circle of Life (Magic Stone MSD030), was released in October of 1998.

Lost in the shuffle in the lawsuits and new recordings are the other singers on this original Ami song, Panay, Afan, and Kacaw, according to “True Feelings from the Bosom of Nature,” Sinorama Magazine, <http://www.gio.gov.tw/info/sinorama/8508/5080/161e.html>. This URL is no longer active.

28. “IOC President to Thank Ami Singers.”

29. “Ami Sounds Scale Olympian Heights.”

30. “From Betelnuts to Billboard Hits.”

31. “Ami Sounds Scale Olympian Heights.”

32. “Olympic Music from Taiwan.” This is the figure also reported on the Internet newsgroup <misc.activism.progressive> by someone who seems to be an activist on behalf of the Kuos.

33. “Ami Sounds Scale Olympian Heights.”

34. Deborah Kuo, “Taiwan Aborigines Sue Enigma, Music Companies,” Central News Agency, March 28, 1998; and “Taiwan Couple Sue Enigma Over Vocals on International Hit,” Associated Press, March 27, 1998.

35. “dcd” refers to the Australian band Dead Can Dance.

36. E. Patrick Ellisen, telephone communication, February 16, 1999.

37. E. Patrick Ellisen, telephone communication, April 21, 1999.

38. Quoted in Huang, “Golden Oldie,” 62.

39. Brenda Sandburg, “Music to Their Ears,” Recorder, June 24, 1999, 1. See also Victor Wong, “Taiwan Aboriginal Singers Settle Copyright Lawsuit,” Billboard, July 31, 1999, 14.

40. The Hakka people were a migratory group who were persecuted at various times by the native peoples in whose territories they settled.

41. From <http://www.mpath.com/~piaw/bunny/shinbao.htm>. This URL is no longer active.

42. It is included on the soundtrack to the film Chinese Box, Blue Note 93285, 1998.

43. This is a common discourse by Western musicians and fans about non-Western musics—they are simply raw material for the genius of the Western star. See, for example, Paul Simon’s discussion of his work with black South African musicians on Graceland in the documentary Paul Simon: Born at the Right Time (Warner Reprise Video, 1992), in which he clearly narrates himself as an adventurer/explorer going into the heart of darkest Africa to bring back natural, unrefined materials that he transforms into something valuable and worthy. See also Timothy D. Taylor, Global Pop, chap. 1, for a more general discussion of this assumption.

44. Enigma FAQ, <http://www.spikes.com/enigma/>.

45. Quoted in Sally Price, Primitive Art in Civilized Places (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 100.

46. <http://www.spikes.com/enigma/Mambo1.html>. This URL is no longer active.

47. Ibid. Cretu and Enigma were sued for a sample on their earlier recording. An interview with Cretu published in Norway in 1990 says that “the Gregorian church chant is recorded in Rumania, and [Cretu] answers frenetically affirmative when we wonder if the singing monks have received their share of all the D-marks he gets” (Catharina Jacobsen, “Michael’s Mystical Music,” Verdens Gang (Oslo, Norway), December 19, 1990 [trans. Joar Grimstvedt], available at <http://www.stud.his.no/~joarg/Enigma/articles/verdensGang1290.html>). But it later transpired that the recording was made in the 1970s by the Munich-based choir Kapelle Antiqua, which recognized its recording of chant sampled on the Enigma album. Even though this recording is in the public domain (and it is not clear why), the group sued, claiming that Cretu had infringed on its “right of personality.” The group settled out of court. Billboard’s report on the suit says that “it is understood that the bulk of the money paid to Kapelle Antiqua is in recognition of the infringement of its ‘right of personality.’ Lesser sums have been paid to the record companies Polydor and BMG/Ariola for the unauthorized use of master recordings” (Ellie Weinert, “‘Sadeness’ Creator Settles Sample Suit,” Billboard, September 14, 1991, 80).

48. Simon Frith, “Music and Morality,” in Music and Copyright, ed. Simon Frith, Edinburgh Law and Society Series (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993), 8.

49. Ellie Weinert, “‘Changes’ in Works for Enigma,” Billboard, January 8, 1994, 10.

50. Dominic Pride, “Virgin Stays with Proven Marketing for Enigma,” Billboard, November 23, 1996, 1.

51. Review of The Cross of Changes, <http://www.hyperreal.com/music/epsilon/reviews/enigma.cross>. This URL is no longer active.

52. “Olympic Music from Taiwan.”

53. See Douglas Rushkoff, “Conspiracy or Crackpot? Cyberlife US,” Manchester Guardian, November 14, 1996, 13.

54. Paul Fisher, “Connected: Log and Learn Encyclopedia,” Daily Telegraph (London), December 11, 1999, 10.

55. Here are just some of the newspaper reports on the Encarta discrepancies: Charles Arthur, “How Many People Does It Take to Invent the Lightbulb?” Independent (London), June 26, 1999, 13; Kevin J. Delaney, “Microsoft’s Encarta Has Different Facts for Different Folks,” Wall Street Journal, June 25, 1999, A1; and Stephen Moss, “Your History Is Bunk, My History Is Right,” Manchester Guardian, June 29, 1999, section G2, p. 4.

56. Liner notes to Polyphonies Vocales des aboriginès de Taïwan, Inedit, Maison des Cultures du Monde, W 2609 011, 1989.

57. These “ethnotechno” musics generally display a different attitude toward the sampled material, however. It’s usually less foregrounded in the mix; the samples tend to be shorter; and the samples are not usually put to New Age ends, as in Enigma’s song. See Taylor for a discussion of the differences between these electronic musics and their uses of samples. For more on “ethnotechno,” see Erik Goldman, “Ethnotechno: A Sample Twist of Fate,” Rhythm Music, July 1995, 36– 39; Josh Kun, “Too Pure?” Option, May/June 1996, 54; and Jon Pareles, “A Small World After All. But Is That Good?” New York Times, March 24, 1996, H34.

58. Nancy Guy, email communication, March 29, 1999. See also Guy’s “Techno Hunters and Gatherers: Taiwan’s Ami tribe, Enigma’s ‘Return to Innocence’ and the Legalities of Cultural Ownership,” paper presented at the Society for Ethnomusicology, Bloomington, Indiana, October 22, 1998.

59. Juping Chang, “Ami Group Sings of Bittersweet Life in the Mountains,” Free China Journal, January 1, 1999, <http://publish.gio.gov.tw/FCJ/fcj.html>. This URL is no longer active.

60. Ibid.

61. I am very grateful to Dale Wilson for providing a translation of the liner notes. For sources on the concept of self-exoticization and self-Orientalism, see Shuhei Hosokawa, “Soy Sauce Music: Harumi Hosono and Japanese Self-Orientalism,” in Widening the Horizon: Exoticism in Post-War Popular Music, ed. Philip Hayward (Sydney: John Libby, 1999); Koichi Iwabuchi, “Complicit Exoticism: Japan and its Other,” Continuum 8 (1994): 49–82; and Joseph Tobin, Re-Made in Japan: Everyday Life and Consumer Taste in a Changing Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

62. Liner notes to Difang, Circle of Life, Magic Stone Music MSD-030, 1998.

63. Deep Forest sampled music from all over Africa. Released in Europe in 1992, it proved to be one of the bestselling albums on college campuses in 1993– 94, selling over 1.5 million copies in the United States alone. For more on Deep Forest, see Carrie Borzillo, “Deep Forest Growing in Popularity,” Billboard, February 19, 1994, 8, and “U.S. Ad Use Adds to Commercial Success of Deep Forest,” Billboard, June 11, 1994, 44; Steven Feld, “Pygmy Pop: A Genealogy of Schizophonic Mimesis,” Yearbook for Traditional Music 28 (1997): 1–35, and “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music,” Public Culture 12 (winter 2000): 145–71; René T. A. Lysloff, “Mozart in Mirrorshades: Ethnomusicology, Technology, and the Politics of Representation,” Ethnomusicology 41 (spring/summer 1997): 206–219; Andrew Ross, review of Deep Forest, Artforum 32 (December 1993): 11–13; the extensive FAQ at <http://www.spikes.com/worldmix/faq.htm>; Hugo Zemp, “The/An Ethnomusicologist and the Record Business,” Yearbook for Traditional Music 28 (1997): 36–56; and <http://www.music.sony.com/Music/ArtistInfo/DeepForest.html>.

Deep Forest took Lee’s advice. Wind Records was established in Taiwan to preserve traditional musics. But it was one of their collections that found its way onto Boheme, on which Deep Forest sampled a selection from a CD entitled The Songs of the Yami Tribe, vol. 3 of The Music of Aborigines on Taiwan Island, Wind Records, TCD-1503, 1993. According to the Deep Forest FAQ, the Ami sample on Boheme is “A Recitative for Describing Loneliness,” a title so evocative that it would seem hard to pass up (the Deep Forest FAQ is at <http://www.spikes.com/worldmix/faq.htm>). The Yami are a different group than the Ami; it isn’t a different transliteration. The program note accompanying the original Yami recording says that “A Recitative for Describing Loneliness” employs a scale uncommon in Yami music and is borrowed from the Ami. But to Roger Lee, it seems that an aborigine is an aborigine: Can I give you Ami? No? Yami? As usual, this appropriative act by Deep Forest becomes converted into a sales tactic. Next to the entry in Wind Records’ catalog for Yami recordings, there is a little blurb mentioning that “A Recitative for Describing Loneliness” was “excerpted” on Deep Forest’s Boheme.

The sampled song is “Marta’s Song,” Marta being the well-known Hungarian singer Marta Sebestyén. “A Recitative for Describing Loneliness” flits through the background when Sebestyén isn’t singing her folk song (beginning at 1:45). A Hungarian/Transylvanian reader of the Enigma Internet mailing list informs me that this is a traditional song about a woman who is lamenting being pregnant and alone.

64. Anita Huang, “Global Music, Inc.,” <http://www.gio.gov.tw/info/fcr/8/p42.htm>. This URL is no longer active. See also a more recent report on the growing popularity of music with an “Aboriginal flair” in Taiwan: Victor Wong,“Taiwan’s Power Station Brings Aboriginal Flair to What’s Music,” Billboard, July 11, 1998, 48.

65. Steven Feld, “From Schizophonia to Schismogenesis: On the Discourses and Commodification Practices of ‘World Music’ and ‘World Beat,’ ” in Charles Keil and Steven Feld, Music Grooves: Essays and Dialogues (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

DISCOGRAPHY

Chinese Box, Blue Note 93285, 1998.

Dance Mix USA, vol. 2. Quality Music 3902, n.d.

Dance Mix USA, vol. 3. Quality Music 6727, 1995.

Deep Forest. Boheme. 550 Music/Epic BK-67115, 1995.

———. Deep Forest. 550 Music/Epic BK-57840, 1992.

Difang. Circle of Life. Magic Stone Music MSD030, 1998.

Enigma. MCMXC A.D. Capitol 86224, 1991.

Enigma 2. The Cross of Changes. Charisma/Virgin 7243 8 39236 2 5, 1993.

First Generation: 25 Years of Virgin. Virgin 46589, 1998.

High on Dance. Quality Music 6741, 1995.

Lacksman, Dan. Pangea. Eastwest World 61947–2, 1996.

Loaded, vol. 1. EMI America 32393, 1995.

The Music of Aborigines on Taiwan Island, vol. 3, The Songs of the Yami Tribe. Wind Records: TCD-1503.

New Formosa Band. Best Live & New Remix. RD-1345, 1996.

Polyphonies Vocales des Aborigines de Taïwan. Inedit, Maison des Cultures du Monde, W 2609 011, 1989.

Pure Moods. Virgin 42186, 1997.

FILMOGRAPHY

Paul Simon: Born at the Right Time. Warner Reprise Video, 1992.

REFERENCES TO SITES ON THE INTERNET

ftp://ftp.best.com/pub/quad/deep.forest/DeepForest-FAQ.txt

http://www.hyperreal.com/music/episilon/reviews/enigma.cross

http://www.mpath.com/~piaw/bunny/shinbao.htm

http://www.music.sony.com/Music/ArtistInfo/DeepForest.html

http://www.spikes.com/enigma/Mambo1.html

http//www.spikes.com/worldmix/faq/

UNPUBLISHED MATERIALS

Bois, Pierre. Personal communications. 26 March 1999 and 7 April 1999.

Ellisen, E. Patrick. Personal communications. 21 April 1999, 16 February 1999, and 22 February 1999.

Guy, Nancy. Personal communication. 29 March 1999.

———. “Techno Hunters and Gatherers: Taiwan’s Ami tribe, Enigma’s ‘Return to Innocence’ and the Legalities of Cultural Ownership.” Paper presented at the Society for Ethnomusicology, Bloomington, Indiana, 22 October 1998.

Kohler, Frank. Interview with Lifvon Guo [Kuo Ying-nan]. National Public Radio, All Things Considered, 11 June 1996.

MATERIALS AVAILABLE ONLY ON THE INTERNET

Enigma Live Chat Event on the Internet, 13 December 1996.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Ami Sounds Scale Olympian Heights.” Part 1. http://www.gio.gov.tw/info/sinorama/8508/508006e1.html.

“Ami Sounds Scale Olympian Heights.” Part 2. http://www.gio.gov.tw./info/sinorama/8508/508006e2.html.

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Public Worlds, edited by Dilip Goankar and Benjamin Lee, no. 1. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Arthur, Charles. “How Many People Does It Take to Invent the Lightbulb?” Independent (London), June 26, 1999, 13.

Bentley, Jerry H. Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Borzillo, Carrie. “Deep Forest Growing in Popularity.” Billboard, February 19, 1994, 8.

———. “U.S. Ad Use Adds to Commercial Success of Deep Forest.” Billboard, June 11, 1994, 44.

Brennan, Timothy. At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now. Convergences: Inventories of the Present. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of Network Society. Vol. 1 of The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1996.

Chang, Juping. “Ami Group Sings of Bittersweet Life in the Mountains.” Free China Journal, January 1, 1999. http://publish.gio.gov.tw/FCJ/fcj.html.

Conte, Christopher. “A Special News Report on People and Their Jobs in Offices, Fields and Factories.” Wall Street Journal, May 21, 1991, sec. A, p. 1.

Delaney, Kevin J. “Microsoft’s Encarta Has Different Facts for Different Folks.” Wall Street Journal, June 25, 1999, A1.

Enigma FAQ. http://www.stud.his.no/~joarg/.

Esarey, Ashley. “An Ami Couple Seeks Recognition for Their Music.” http://www.sinica.edu/tw/tit/special/0996_Innocence.html.

Feld, Steven. “From Schizophonia to Schismogenesis: On the Discourses and Commodification Practices of ‘World Music’ and ‘World Beat.’ ” In Charles Keil and Steven Feld, Music Grooves: Essays and Dialogues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

———. “Pygmy Pop: A Geneaology of Schizophonic Mimesis.” Yearbook for Traditional Music, 28 (1997): 1–35.

———. “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music.” Public Culture 12 (winter 2000): 145–71.

Fisher, Paul. “Connected: Log and Learn Encyclopedia.” Daily Telegraph (London), December 11, 1999, 10.

Frith, Simon. “Music and Morality.” In Music and Copyright, edited by Simon Frith. Edinburgh Law and Society Series. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993.

“From Betelnuts to Billboard Hits.” http://pathfind.com/@@CkDcMAcA0VE9Uaiw/Asiaweek/96/1122/feat5.html.

Goldman, Erik. “Ethnotechno: A Sample Twist of Fate.” Rhythm Music (July 1995): 36–39.

Guilbault, Jocelyne. “On Redefining the ‘Local’ Through World Music.” World of Music 32 (1993): 33–47.

Hall, Stuart. “The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity” In Culture, Globalization and the World-System, edited by Anthony D. King. Current Debates in Art History, no. 3. Binghamton, N.Y.: Department of Art and Art History, State University of New York at Binghamton, 1991.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. Studies in the History of Religions, no. 72. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996.

Hayward, Philip. “Cultural Tectonics.” Convergence 6 (spring 2000): 39–47.

Heelas, Paul. The New Age Movement: The Celebration of the Self and the Sacralization of Modernity. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1996.

Henwood, Doug. “Post What?” Monthly Review 48 (September 1996): 1–11.

Hosokawa, Shuhei. “Soy Sauce Music: Harumi Hosono and Japanese Self-Orientalism.” In Widening the Horizon: Exoticism in Post-War Popular Music, edited by Philip Hayward. Sydney: John Libby, 1999.

Huang, Anita. “Global Music, Inc.” http://www.gio.gov.tw/info/fcr/8/p42.htm. (This URL is no longer active.)

Huang, Renata. “Golden Oldie.” Far Eastern Economic Review (November 2, 1995): 62.

“IOC President to Thank Ami Singers.” Free China Journal, http://ww3.sinanet.com/heartbeat/fcj/0726news/16_E.html.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. “Complicit Exoticism: Japan and Its Other.” Continuum 8 (1994): 49–82.

Jacobsen, Catharina. “Michael’s Mystical Music.” Translated by Joar Grimstvedt. Verdens Gang (Oslo, Norway), December 19, 1990, http://www.stud.his.no/~joarg/Enigma/articles/verdensGang1290.html.

Kraidy, Marwan M. “The Global, the Local, and the Hybrid: A Native Ethnography of Glocalization.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 16 (December 1999): 456–76.

Kun, Josh. “Too Pure?” Option (May/June 1996): 54.

Kuo, Deborah. “Taiwan Aborigines sue Enigma, Music Companies.” Central News Agency, March 28, 1998.

Liner notes to Difang, Circle of Life. Magic Stone Music MSD-030, 1998.

Liner notes to Polyphonies Vocales des Aborigines de Taïwan. Inedit, Maison des Cultures Du Monde, W 2609 011, 1989.

Lysloff, René T. A. “Mozart in Mirrorshades: Ethnomusicology, Technology, and the Politics of Representation.” Ethnomusicology 41 (spring/summer 1997): 206–219.

Moss, Stephen. “Your History Is Bunk, My History Is Right.” Manchester Guardian, June 29, 1999, sec. G2, p. 4.

“Olympic Music from Taiwan.” http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/smlpp/enigma.htm.

Pareles, Jon. “A Small World After All. But Is That Good?” New York Times, March 24, 1996, H34.

Peak, Martha H. “Developing an International Style of Management.” Management Review, February 1991, 32–35.

Piot, Charles. Remotely Global: Village Modernity in West Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Pride, Dominic. “Virgin Stays with Proven Marketing for Engima.” Billboard, November 23, 1996, 1.

Robertson, Roland. “Globalisation or Glocalisation?” Journal of International Communication 1 (1994): 33–52.

———. “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity.” In Global Modernities, edited by Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash, and Roland Robertson. Theory, Culture and Society. London and Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage, 1995.

Root, Deborah. Cannibal Culture: Art, Appropriation, and the Commodification of Difference. Boulder: Westview Press, 1996.

Ross, Andrew. Review of Deep Forest. Artforum 32 (December 1993): 11. Rushkoff, Douglas. “Conspiracy or Crackpot? Cyberlife US.” Manchester Guardian, November 14, 1996, 13.

Sandburg, Brenda. “Voices in the Copyright Wilderness.” Recorder, December 7, 1998, 1.

Taylor, Timothy D. Global Pop: World Music, World Markets. New York: Routledge, 1997.

———. Strange Sounds: Music, Technology and Culture. New York: Routledge, 2001.

———. “World Music in Television Ads.” American Music 18 (summer 2001): 162–92.

“True Feelings from the Bosom of Nature.” Sinorama Magazine, http://www.gio.gov.tw/info/sinorama/8508/5080/161e.html

Virilio, Paul. Open Sky. Translated by Julie Rose. London and New York: Verso, 1997.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. Historical Capitalism. London: Verso, 1983.

———. The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. Studies in Social Discontinuity, edited by Charles Tilly and Edward Shorter. New York: Academic Press, 1974.

Weinert, Ellie. “‘Changes’ in Works for Enigma.” Billboard, January 8, 1994, 10.

———. “‘Sadeness’ Creator Settles Sample Suit; Will Compensate for Unauthorized Usage.” Billboard, September 14, 1991, 80.

Wilson, Rob, and Wimal Dissanyake, eds. Global/Local: Cultural Production and the Transnational Imaginary. Asia-Pacific: Culture, Politics, and Society. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996.

Wong, Victor. “Taiwan’s Power Station Brings Aboriginal Flair to What’s Music.” Billboard, July 11, 1998, 48.

Zemp, Hugo. “The/An Ethnomusicologist and the Record Business.” Yearbook for Traditional Music 28 (1997): 36–56.