Plugged in at Home

Vietnamese American Technoculture in Orange County

Deborah Wong

It’s all so hard to explain! But through the book, and through the CD-ROM, you can understand me. (Pham Duy in conversation, 1995)

It is no longer possible for a social analysis to dispense with individuals, nor for an analysis of individuals to ignore the spaces through which they are in transit.

(Marc Augé [1995: 120])

This chapter is an extremely localized consideration of one musician and a representation of one piece of music. Ethnographies of the particular offer special rewards as well as a corrective to certain habits in cultural studies. My consideration of the Vietnamese composer Pham Duy1 in the context of Vietnamese American2 technoculture is self-consciously placed at the intersection of cultural studies and ethnography, i.e., I work within an expectation of cultural construction amidst the free flow of power, but I believe that the best way to get at its workings is through close, sustained interaction with the people doing it and an obligation to address their chosen self-representations.

I begin with the assumption that technology is a cultural practice and that an examination of technological practices in context is the only way to get at what technology “does.” Until recently, far too much of the literature on technology has treated it as something outside of or beyond culture, or has simply valorized technology as a force with specific effects and outcomes (such as cultural gray-out). I assume, on the other hand, that any technology is not only culturally constructed but that its uses are culturally defined as well; the “same” technology can thus have very different applications and/or evocative associations in different societies. A certain body of thought has viewed technology as inherently destructive to “tradition,” but I regard this too as a historicized cultural belief system rather than a given; if anything, I err in the other direction, assuming that technology carries with it the potential for democracy and community building.3

Current work on communication and technology is increasingly informed by cultural studies and anthropology, and “the hypodermic needle theory” of mass communication and its effects is now routinely cited and discarded. In a discussion of audience studies and its contentious interface with cultural studies and ethnography, communications theorists James Hay, Lawrence Grossberg, and Ellen Wartella (1996: 3) note that “the one general area of consensus across this range of shifting, occasionally contradictory positions was their rejection of the ‘hypodermic needle’ conception of communication which assumed (some long time ago) that audiences were passive receptors—tablets on which were written media messages.” Cultural studies provides effective tools for getting at agency without ruling out the possibility of coercion, rather treating it as one dynamic among many. Undoubtedly, technology and the media have effects, but new theoretical models enable considerations of multidirectional results in which production and reception are no longer constructed as binaries or as mutually exclusive. Constance Penley and Andrew Ross address these matters (and their historical background) with a keen sense for how theories of technology are bifurcated, noting that editing their groundbreaking collection Technoculture led them to be “wary, on the one hand, of the disempowering habit of demonizing technology as a satanic mill of domination, and weary, on the other, of postmodernist celebrations of the technological sublime” (1991: xii).

I focus here on an example of localized production that raises interesting questions about reception. In his groundbreaking book on Chinese American karaoke, Casey Man Kong Lum notes that most media studies have focused on texts “such as television programs, popular magazines, and romance novels [that] do not involve their audiences in the process whereby their semiotic resources are produced” (1996: 16). Without ruling out the possibility that audiences can read against a text, Lum argues that “audiences are certainly limited in the extent to which they can negotiate meaning because they interpret on the grounds built by others” (ibid.). While I think one can locate the production of semiotic resources nearly anywhere, it is not helpful to simply level the field in reaction to earlier models that locked making and receiving into particular sites. There are always reasons for locating cultural production in particular places, and the Vietnamese composer Pham Duy has reasons for turning so single-mindedly to local, family-based output.

Television is one of the major forms of technoculture that has undergone extended crosscultural study. In the West, theorists have argued that television causes social isolation and alienation, but the American anthropologist Conrad Kottak has countered that considerable ethnocentrism lies behind studies like the Annenberg School of Communication’s project finding that heavy television watching leads to the “cultivation effect,” wherein viewers begin to believe that the real world is similar to whatever they see on television (1990: 11). While this may be true for Americans watching American programming, Kottak maintains that television watching in Brazil follows different patterns, whether in the cities or in remote rural areas. He and his research team found, among other things, that many Brazilians watch TV in groups—not alone in their homes—and that, in rural areas, people with TV sets in their homes are expected to open their windows so that neighbors can watch from the street (Pace 1993). Furthermore, television clearly expanded Brazilians’ understandings of regional and social differences within their own country as well as their knowledge of the rest of the world; Kottak concludes (1990: 189) that “Brazilian televiewing expresses and fuels hunger for contacts and information…. Our village studies confirmed that television can (1) stimulate curiosity and a thirst for knowledge (2) increase skills in communicating with outsiders (3) spur participation in larger-scale cultural and socioeconomic systems, and (4) shift loyalties from local to national events.” Overall, Kottak finds that “TV is neither necessarily nor fundamentally an isolating, alienating instrument” (1990: 189). If it is isolating and alienating in the United States, then this is a particular cultural response to the technology.

Similarly, ethnomusicologists have addressed particular technomusical artifacts as expressions of localized community issues and concerns. Mark Slobin’s work on sheet music as a cultural technology for Jewish immigrants (1982) was an important first step toward conceptualizing the physical products of music cultures as expressions of local conflicts and challenges. More recently, cassette culture has attracted a lot of attention. One line of work treats cassettes as physical texts that can undergo cultural analysis (Wong 1989/1990, Manuel 1993); another follows Slobin’s lead and focuses on localized cassette industries for issues of identity work (Sutton 1985, Castelo-Branco 1987). The shifting space between production and consumption has also been redefined. Popular music theorist Steve Jones (1990) addresses how the accessibility of cassette recording puts production into the hands of nearly anyone, thus generating a “cassette underground” of popular music that rejects the values of the music industry. Ethnomusicologist Amy Catlin refers to Hmong American practices of recording young women’s courtship songs on cassette (a traditional practice maintained in the diaspora) and circulating them widely—between Rhode Island and California, for instance—and notes that some young women no longer rely on matchmakers but make and distribute the tapes themselves (1992: 50, 1985: 85 for a photograph). Anthropologist Susan Rodgers (1986) considers the role of cassette recordings of music drama for the Batak of northern Sumatra, concluding that the tapes are “cultural texts” in which the Batak both confront and mediate issues of kinship and ethnic identity. More recently still, some ethnomusicologists have begun to consider how cassettes are used, regarding them as sites for social action based in local concerns (see Greene 1995 and 1999 for detailed ethnographies of cassette use in a Tamil Nadu village). In short, the physical byproducts of certain music technocultures—cassettes in particular—have been treated rather differently over time in response to changing theoretical landscapes. Significantly, research has addressed urban popular musics as well as rural “traditional” musics, finding redefinition through local use in both contexts.

Locating Little Saigon

I have been fascinated by Little Saigon ever since I first visited it in 1991. Little Saigon is the largest Vietnamese community outside of Vietnam and is the unofficial capital of the Vietnamese diaspora.4 Located in the contiguous suburban towns of Westminster, Garden Grove, Midway City, and Santa Ana in Orange County, California, it is a site of intense mediation. By mediation, I refer to all the forms of technoculture found in everyday life, and I use the term to point to the ways technology is culture; culture is always mediated (i.e., dialogically shaped and filtered), but I am here concerned with the roles of technology in shaping Vietnamese American memory and political resistance. Driving along the broad suburban thoroughfares of Little Saigon, you can’t miss these characteristics of the community: its strip malls are full of video and music stores devoted to Vietnamese American singers and songs. Every mall has at least one if not several stores stuffed full of cassettes, CDs, videotapes, and laser disks.5 I have discussed the centrality of mediated music to Little Saigon elsewhere, in an article on the social importance of Vietnamese American karaoke (Wong 1994), and I consider this essay a companion piece—a look at a rather intense site of production that complements my consideration of karaoke as both consumption and production.

Fig. 1. Little Saigon strip mall with karaoke store. (Photograph by Deborah Wong.)

Adelaida Reyes (1999a: 152) suggests that the Vietnamese American music industry has changed culture practices, writing that “for most Vietnamese, the love for music has been deflected from performing to listening. As one Vietnamese put it, their musical life is now lived largely through audiocassettes.” She looks briefly at the Orange County industry and finds that most recording artists were their own producers, doing all their own marketing and distribution (1999a: 157). She describes the process as follows (ibid.):

Once the recording and duplicating are finished, they contact the dealers to announce the availability of the new product. Some of the dealers are large audio stores but many are small establishments—bookstores or specialty shops. Artists distribute and sell locally, nationally and internationally. It is a tremendous amount of work and Pham Duy considers himself lucky because he has family members who share the work: he “creates”; his son [Duy Cuong] is the “fabricateur,” running the publishing and recording enterprises; his daughters are singers; and his daughter-in-law travels abroad to manage the distribution which is worldwide.

Reyes also provides a fascinating glimpse of the crosscultural negotiations she witnessed between a Vietnamese singer and an American sound engineer during a recording session in a professional studio (1999a: 153–55). The singer was there to overdub a pre-prepared tape of American instrumental musicians playing the accompaniment and was thus locked into given tempos, unless the tape was played faster (thus raising the overall register). At one point, the sound engineer tried to dissuade her from the expected Vietnamese practices of sliding into pitches and ornamenting her line. Reyes suggests that their interaction mirrored Vietnamese/American cultural negotiation more broadly, noting that “There were no overt conflicts. There was considerable but not total loss of control on the part of the recording artist” (1999a: 154).

Little Saigon has a fascinating immigrant mass media industry in its own right, but it is also a terrific site through which to consider theories of mass communication. To oversimplify, one of the perennial questions in media studies is who drives whom? Does the mass media drive people, or vice-versa? Neo-Marxist theorists assert that media technologies create and sustain hegemonic holds over communities and populations, but cultural studies theorists look for fissures that suggest otherwise. I fall into the latter camp, not so much out of any romantic, totalizing belief that the lumpen proletariat ought to have a voice, but because I think both theoretical stances help us to see certain political realities: they help us to understand the consequences of certain technologies as well as to see how envoicing can happen (when it does), sometimes despite tremendously powerful counter-assertive forces. In Big Sounds from Little Peoples, Wallis and Malm argue that the multinational music industry has been very difficult to resist, noting that “Governments will … have to create systems for redistributing money to cover the expenses involved in keeping local music life alive and flourishing” (1984: 322). While issuing a stern warning about the might of multinational industry, Wallis and Malm maintain great optimistic belief in cultural response, taking pains to avoid demonizing technology: “Whichever way it goes, technology will play an important role. But technology alone will not determine the outcome. People and governments do that” (1984: 324). I will follow their lead and start by discarding the equation that technology equals hegemony: technology is culture, and culture is shaped by resistance as well as acceptance. We also need to look hard at what we call resistance, to be sure we see the messy internal politics that can grant resistance an even more interesting profile.

I consider a single technocultural artifact here as an example of these issues, and turn now to Pham Duy, one of Vietnam’s preeminent composers; any Vietnamese or Vietnamese American would not only know his name but would probably be able to sing at least one of his songs. Adelaida Reyes (1999a: 68) writes, “I have not met a Vietnamese who did not know the name, Pham Duy, Vietnam’s best known composer, and his use of folk and traditional materials in the music he created and performed—music subsequently heard all over Vietnam as a powerful rallying cry around Vietnamese nationalism during the war against the French.” Pham Duy was born in North Vietnam in 1921 and emigrated to the United States in 1975; he is seventy-seven years old at the time of this writing and lives in Little Saigon (Midway City). He is a noted composer of songs as well as a folklorist: his book, Musics of Vietnam (1975), is one of the few extended English-language overviews of Vietnamese music. Pham Duy’s life covers all of the momentous events of twentieth-century Vietnamese history. He fought against the French in the 1950s as a member of the Viet Minh (the Vietnamese resistance) and later fell out with the Communists over ideological matters;6 his songs are still banned in Vietnam as a result. His name is inextricably linked to the creation of Vietnamese “new music” (nhac cai cach, “reformed music,” or tan nhac, “modern music”), created from the 1920s to the 1940s by Vietnamese composers well versed in Western musical vocabularies and instruments but wanting to reinvigorate Vietnamese music. Ethnomusicologist Jason Gibbs (1997: 9–10) notes that “this reformed music was not clearly defined, but was generally used to denote the new western-style music composed by Vietnamese” and suggests that it led to the Vietnamese adoption of the artistic figure of the composer. Gibbs also notes that many of the Vietnamese composers associated with this movement made a point of studying traditional Vietnamese folk musics (Gibbs 1998) and that part of their motivation was to change the rather low regard in which many traditional musics were then held.7

Pham Duy is an outgoing, energetic man, fluent in French and English as well as in Vietnamese; he constantly goes on lecture tours to Vietnamese communities in the United States and in Western Europe to promote new projects. He is very comfortable making public presentations, and he clearly enjoys talking about his work; he is well known and admired for his promotional skills. He has lived in the Little Saigon area for almost twenty years: he is extremely resourceful and has continued to compose and to make sure that his music gets disseminated. A fiend for music technology, his home on a quiet residential street near the main drag of Little Saigon is also his studio and his business. He has state-of-the-art computers (a PC, a Macintosh, and a PC laptop), several MIDI keyboards, and any number of DAT recorders. At one point I asked him why he thought that the older generation generally doesn’t explore new forms of technology, and he retorted, “Because they are fools! But I am a workaholic, a computerholic.” A self-taught computerholic, he composes using a synthesizer and creates computer-generated sheet music that he publishes; he is well versed in HTML software and designed his own webpage, which is constantly growing (<http://www.kicon.com/Music.html>, then follow the links to Pham Duy’s pages). With the help of his wife and their adult children, he records and packages cassettes and CDs of his works, which are distributed to countless shops in Orange County and far beyond.

Pham Duy’s is one of many Vietnamese American home music businesses in Little Saigon, though it is certainly among the most technologically sophisticated. This is significant because Little Saigon is the center of the Vietnamese American mass media: if you buy a Vietnamese American cassette anywhere in the United States, it was almost certainly produced in Westminster, Garden Grove, or any of the townships that constitute Little Saigon. Vietnamese American newspapers, videos, and television news programs are also disseminated nationwide out of Little Saigon. The community is marked by a stunningly varied local mass media that permeates the area.

In fact, a major Internet project in Garden Grove has a central role in the Vietnamese diaspora. Some work in cultural studies has questioned whether virtual space is “real” social space, but this simply is not an issue for many Vietnamese Americans (and indeed for other immigrant communities, especially those created by forced migration). The Vietspace website (<http://www.kicon.com>) was created in 1996 and was logging over 10,000 hits a day in 1998; it has become “one of the premier meeting places—a 21st-century town square—for a worldwide community of refugees spread across thousands of miles,” according to an article in the Los Angeles Times (Tran 1998). The site was created and is maintained by Kicon, a multimedia software company in Garden Grove that is owned and run by Vietnamese Americans. Although there are dozens of other websites devoted to the Vietnamese community in diaspora, Vietspace is certainly the most extensive and up-to-date, as it is revised daily. It contains postings of articles from Vietnamese newspapers, wire reports from Vietnam, and radio broadcasts from the Vietnamese station in Westminster, all downloadable for free via audio and video hookups; samples of music videos, film clips, and songs by Vietnamese artists (including Pham Duy) are available, as well as a virtual art gallery of paintings by well-known Vietnamese artists. Most importantly, a missing-persons page allows Vietnamese to search for parents, children, friends, and colleagues who were separated after 1975: some people post photographs along with their personal information, and a number of reunions have resulted. In short, the site creates real connectedness, not simply imagined community, and is a vital link between farflung members of the Vietnamese community in the United States and beyond.

Fig. 2. Pham Duy in his kitchen, with CD packaging in progress. (Photograph by Deborah Wong.)

Still, questions of access and its relationship to socio-economic class must be asked for any form of technology, including the web. In some ways, the web is remarkably open and democratic; in other ways, it is linked to hardware that is not widely available in public institutions and that still requires a significant outlay of money. The Vietnamese American community is markedly differentiated and does not have unilateral access to mass communication forms. The major line of demarcation in Vietnamese American identity is relative generation and, after that, arrival date in the United States: the refugees who arrived between 1975 and about 1979 were largely middle- to upper-class Vietnamese whose connections to U.S. government officials facilitated their emigration; some were able to bring financial reserves with them. These immigrants founded Little Saigon and continue to play a leading role in (especially) the business life of the community. The second wave of emigration was characterized by many so-called boat people, who left Vietnam under dire circumstances, often enduring years of relocation camps (in the Philippines, Thailand, and Hong Kong) before resettlement in the United States or elsewhere; this group has found it harder to find a foothold in relocation, as many left Vietnam with few personal resources. Other differences include religion; Vietnamese can be Catholic, Buddhist, or Methodist, and the churches have become community centers for distinct groups of Vietnamese. Finally, respective generation creates fundamental lines of difference within the Vietnamese community, as the second generation and members of the 1.5 generation (those who were born in Vietnam but emigrated to the United States as children or young adults) are often more acculturated to American society and will ideally have different opportunities available to them. All these factors have effects on access to new forms of mass communication technologies. The newspaper article cited above contains a telling anecdote about an elderly Vietnamese man in Toronto who “made a ritual” (Tran 1998) of going to his son’s home each morning and waiting for the son to log on to the computer so that he could listen to a radio program from Little Saigon posted to Vietspace; his son was his link to Internet access. Missing from the picture of a mediated Vietnamese America are the Vietnamese who can’t yet afford a computer or the monthly fee for a browser (like several Vietnamese American undergraduates I know in nearby Riverside, California, where I teach). The community is thus heavily mediated (and mediating), but unilateral contact and participation in new forms of technology cannot be assumed.

Voyage through the Motherland on CD-ROM

Pham Duy has consistently experimented with different technological forms. Indeed, he has participated in virtually all of the major forms of twentieth-century mass communication. As a young man, he left his home in North Vietnam to travel as a cai luong8 singer in a troupe called the Duc Huy Group, touring Vietnam from north to south from 1943 to 1945. He was the first to sing the so-called “new music” (nhac cai cach) for Radio Indochine in Saigon in 1944 on a twice-weekly program. Indochine was the first radio station in Vietnam, established by the French but featuring programs in French and Vietnamese from the beginning. Pham Duy was thus in on the ground floor of this fundamentally important form of mass media, and he quickly became well known through it. He joined the Vietnamese resistance in 1945, and broadcasts in which he sang his songs, many about a free Vietnam, were a regular feature of the Viet Minh clandestine radio, transmitted from a cave just outside Hanoi in the north. He writes, “a gun in one hand and a guitar in the other, I went to war with songs as my weapon” (1995: 25).

He is very forthright about the role of the political in his life and work, and he doesn’t see its centrality as unusual. He said to me, “In Vietnam, everything—music, poetry—has to do with politics. You cannot avoid it. If you didn’t have this situation in Vietnam, you wouldn’t have me.”9 The “modern music” style in which he writes has an inherently political base, as its genesis was in Vietnamese intellectuals’ rejection of French cultural hegemony. Although its Western influence is obvious to a Western ear, the fact that it was written by Vietnamese for Vietnamese listeners means everything for its followers. Its anticolonial ideological foundation had a powerful effect on Vietnamese audiences in the 1930s, as Pham Duy has written in his autobiography (1995: 18): “Modern music … had [a] strong psychological impact upon the mentality of Vietnamese youth. Gone were the patriotic songs written to ancient Chinese or French tunes, poorly made up, too simple and very much unpolished. The new musical language provided musicians with better means to express emotions and sophisticated feelings. Many realised how powerful music can be and used their songs to stir patriotic sentiment especially among the youth, who would play the key role in the fight against the French colonialists.”

Fig. 3. Pham Duy in the 1940s. (Photograph reproduced with the permission of Pham Duy.)

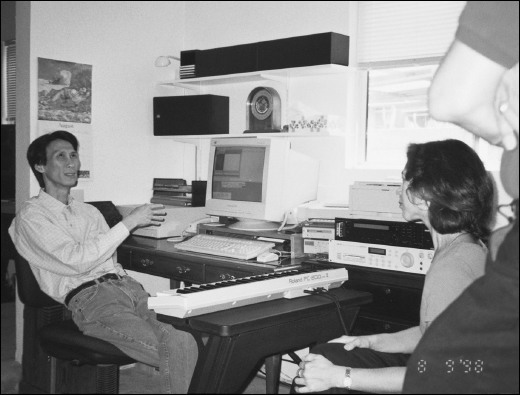

Since his arrival in the United States, he has formed several production companies, including “Pham Duy Enterprises” and “PDC Productions,” named for himself and his son (Pham + Duy + Cuong). Duy Cuong came to the United States at the age of twenty-one in 1975; he is very adept with new forms of music technology (even more than his father, as Pham Duy readily admits), and the two have collaborated extensively. I have long been fascinated by musicians’ home studios as actual sites of cultural production. Duy Cuong’s skill with music software is the other half of Pham Duy Productions, their joint business. He works in a Macintosh platform, using Sample Cell II as his main program for mapping and numerous other programs for sound editing, including Sound Designer II, Alchemy, Hyper-Prism, Infinity Looping, Wave Convert, TimeBandit (for changing a tempo without changing pitch), HyperEngine, Medicine (which allows him to see sound waves and to visually edit them), and Sound Edit. His rack-mounted hardware, set up in his study at Pham Duy’s home, lines one wall of the room and includes lots of MIDI sampling processors, e.g. Proteus I and II, Proteus World (for samples of non-Western instruments), two versions of Rack Mount with numerous piano samples, Vintage Keys (with samples of other kinds of keyboards), Music Workstation, a CD writer, and his latest purchase, a 24-bit mixer with a fiberoptic cable connecting it to his computer’s CPU. He creates the finished albums, working closely with his father; no mere sound engineer, he is a collaborator of the closest kind.

When Pham Duy first began releasing his music in California (shortly after 1975), he used cassettes, and he continues to do so, but he was also the first Vietnamese American to issue his music on CD; CDs are now ubiquitous in the community, as other production companies picked up the medium once it became clear that they sold. His first CD-ROM appeared in 1995 and is centered on a song cycle whose title is variously translated as either The Mandarin Road, The National Road, or Voyage through the Motherland (Truong Ca Con Duong Cai Quan) and that contains elaborate discussions of his life and work. Voyage through the Motherland is arguably Pham Duy’s most famous composition. It was composed between 1954 (the year that the Geneva Accord divided Vietnam into two countries) and 1960 and has since come to symbolize a united Vietnam, especially for the Vietnamese now abroad. The work features three large sections (titled “North,” “Central,” and “South,” for the regions of Vietnam) and a total of nineteen songs; the piece depicts a traveler journeying from north to south Vietnam along the Mandarin Road, a highway that runs the entire length of the country. Each movement draws on regional folk melodies, giving the work tremendously strong affective power for Vietnamese Americans, who thus hear it as a nostalgic affirmation of a single Vietnam and, simultaneously, as a strong statement against Communism. When I played Duy Cuong’s symphonic arrangement of his father’s piece for the undergraduates in my course on Southeast Asian musics in 1992, for instance, the three young Vietnamese American women in the class all asked if they could copy the tape, saying that they wanted to listen to it again and again. The work is deeply symbolic, but it arose from Pham Duy’s personal experiences. He writes (1995: 68) that he has walked the length of the route four times: “In my life, … I have walked on “the mandarin route” four times. The first time when I was a singer of a drama and music troupe [cai luong] touring from Hanoi to Saigon. The second time when I left the south to come home after the return of the Expeditionary French Corps in Vietnam in 1945. The third time when, after a few months of training in Hanoi, I went back to the South, joining the resistance. Then in the fall of 1946, when I was slightly wounded, I left … to return to Hanoi.”

Fig. 4. Duy Cuong in his studio. (Photograph by Deborah Wong.)

Fig. 5. Cover of the CD-ROM version of Voyage through the Motherland (Truong Ca Con Duong Cai Quan). (Reproduced with the permission of Pham Duy and Coloa, Inc.)

He notes that he began work on the piece in 1954, just after “the great nations of the two capitalist and communist forces agreed, through the Geneva Conference, to divide Vietnam in two parts” (1995: 68). He heard the news while on a ship, en route to Paris to study at the French Institut de Musicologie. He writes in his autobiography that he “decided to protest” this political outcome with his music, through the piece that eventually became Voyage through the Motherland.

This work is well known in the different Vietnamese American communities. Adelaida Reyes (1999a: 84–88) describes its performance during a New Year (Tet) celebration in the Vietnamese American community of Woodbridge, New Jersey, in 1984, recounting its arrangement by a local Vietnamese musician into a musical, complete with costumes, scenery, and slides of Vietnam projected onto a screen. Working from the melodies alone (the event took place before the creation and dissemination of Pham Duy’s published score), this musician harmonized it and created a production that emulated Broadway musicals, particularly Nicholas Nickleby, which he had studied closely through tapes. This example—let alone Pham Duy and Duy Cuong’s numerous rearrangements and reissues of the work—suggests that “the piece” has undergone repeated reimagining, and that this process often takes place through other forms of the media and technology.

The CD-ROM of this work is remarkable in a number of ways: it surrounds a single musical work with a number of other histories and leaves it (like all CD-ROMs) up to the user to choose his or her own route through it. It is a profoundly historical document, and it is also intensely multimedia. Among other things, it represents a web of mass-mediated histories and exemplifies Little Saigon’s status as the mass media center of Vietnamese America.

The CD-ROM album was a group effort, the first of a partnership that may result in five to ten more CD-ROMs of Pham Duy’s work. The music and the entire content of the CD-ROM are Pham Duy’s, including the choice of images. The actual programming and design was done by Bui Minh Cuong, a staff member at Coloa, Inc., the company that produced the album.10 The music was arranged for MIDI by Duy Cuong, who has arranged most of his father’s albums after Pham Duy has written the lyrics, melody, and harmonic progressions.

The web site for Coloa, Inc., includes the following description of the contents of the CD-ROM:

• A multimedia presentation of the 11 pieces in the “Con Duong Cai Quan” cycle in which images of historic Vietnamese landmarks, beautiful scenery, bustling cities, quaint towns, and the Vietnamese people and their multifaceted character, will guide the user through the flowing lyrics of the songs.

• Included are multilingual musical narration and song lyrics presented in Karaoke form, in Vietnamese, English and French.

• The adaptation by Duy Cuong of this musical work “Con Duong Cai Quan,” recorded in high fidelity stereo audio. Also included are other Pham Duy’s songs in MIDI formats.

• Video clips of 1954 division of the country

• Several of Pham Duy’s songs performed by Thai Thanh, Khanh Ly, Ngan Khoi Chorus, Bich Lien …

• Commentaries and critiques on Pham Duy’s work by Tran Van Khe, Nguyen Ngoc Bich, Annie Cochet.

• Moments with Pham Duy

• An autobiography of Vietnam’s prolific composer Pham Duy that will have rare insight into his life from the Khang Chien period, through his Tinh Ca works, up to his latest “Hat Cho Nam Hai Ngan” (Songs for the 21st Century). The presentation will be in Vietnamese, English and French.

• Press footage and reviews of “CDCQ” beginning from the ’60’s to present day. Some of the articles are translated to Vietnamese, English and French.

• Glimpses at many famous Vietnamese composers, poets and writers who were Pham Duy’s contemporaries and how they influenced his music. Included in this section are photos of Van Cao, Vu Hoang Chuong, Dinh Hung, Duong Thieu Tuoc, Han Mac Tu, and many more along with their selected works.

• A short electronic book of “My Country Once Upon a Time,” in which PD describes in depth his life journey from his involvement in Khang Chien to his travels throughout VN. Photos of historical landmarks and significant places and cities provide a colorful pictorial guide through VN’s past.

• Complete index and references with hypertext jumps that allow quick and easy access to authors, cities, publications, etc….

• Complete music notes of the whole CDCQ work that is printable.

• Bibliography and discography of other works by PD provided.

Though centered around the one long work, the CD-ROM obviously contains extensive related information. It is all in Vietnamese, but many sections are available in English and French translation (accessed by clicking). An extensive biography of Pham Duy, featuring lots of photographs, provides a colorful look at his life. The short biographies of his musical contemporaries (both singers and composers) offer an overview of the most famous Vietnamese musicians of the twentieth century. Voyage through the Motherland appears in two different mediums. First, the complete musical score in Western notation (done in music notation software) affords the possibility of playing the piece oneself (e.g., on piano). Second, a MIDI karaoke version of the work invites the viewer to participate by singing along while looking at photographs of Vietnamese landscapes and historical sites that fade in and out while song lyrics unfold with the music.

In yet another section, extensive cultural and historical information appears about each of the regions and cities referenced in The Mandarin Road—and, as the piece covers virtually the entire country, this section is essentially an introduction to the culture and history of Vietnam (all in Vietnamese). The bibliography and phonography of Pham Duy’s work maps out a career that spans Southeast Asia, Europe, and the United States. Last but not least, the section offering numerous reviews and discussions of Voyage through the Motherland is staggeringly transnational in scope: the magazine and newspaper articles are in Vietnamese, English, and French; the video excerpt from a television interview with Pham Duy was originally broadcast on Little Saigon TV (showing Pham Duy and a commentator strolling through a park while chatting in Vietnamese); the videotaped excerpt of musicologist Tran Van Khe talking about Pham Duy was shot in Paris; and finally, the video clips of Voyage through the Motherland being performed by Vietnamese Americans were filmed in San Jose and Little Saigon in 1993–94.

This overview is only an indication of the kinds of items found on the CD-ROM album—there is much more, and it would take a viewer many hours to go through the entire document. I am particularly fascinated by the choice of a karaoke version rather than something more “complete,” though vocabulary is a problem in trying to articulate the difference between this and any version not requiring participation. A karaoke version builds in the expectation of interactive involvement, much like CD-ROM technology in itself: both are “activated” by participation. As I argued elsewhere (Wong 1994), karaoke is central to many Vietnamese American social events, from weddings and other parties to informal socializing in restaurants; the Vietnamese American music industry produces hundreds of karaoke videotapes (and many, though fewer, laser disks) every year. One of my Vietnamese American students once invited me to his home for lunch, and the meal was followed by a karaoke session featuring a videotape from Little Saigon that alternated songs in English and Vietnamese, though all were American pop songs; we passed around a microphone that both amplified and added reverberation. Karaoke is central to Vietnamese American social life, so it is no surprise to find it on Pham Duy’s CD-ROM, a strategy meant to encourage interaction beyond clicking the mouse.

Furthermore, the CD-ROM is replete with references to other forms of media—television, radio, etc.—and this is no surprise, as twentieth-century forms of mass communication tend to refer back to or even subsume the forms preceding them, thus creating links both metaphorical and actual. For instance, when CD-ROM drives are used to play audio CDs, the software is designed to look like a CD player on the monitor screen. In this case, the references link Pham Duy’s work to the bigger mediated picture presented by Little Saigon: clips taken from the Little Saigon television station’s programs are part of the connection to a community that exists partly in geographic and social space (in Orange County) and partly in virtual and mass-mediated space. However, I don’t want to call this an imagined community, as much as it lends itself to Benedict Anderson’s powerful construction, because Vietnamese Americans don’t seem to see it as imagined but rather as part of a larger political stance of resistance to the current Vietnamese government.

On the CD-ROM, Pham Duy addresses the importance of computer technology to his work in the United States. Voyage through the Motherland was released on CD in a symphonic version on synthesizer, and an interview with Pham Duy about this earlier release is included on the CD-ROM. The interviewer asks him under what circumstances the work was composed, and after some explanation about the historical context, Pham Duy turns to its new, resourceful arrangement in an American context, saying:

My son (Duy Cuong) and I completed Con Duong Cai Quan in eighteen months using computer technologies. It would not have been a feasible task had it not been for the use of the Music Sequencer software. It is very costly to use a real symphony orchestra concert to compose. An orchestra can cost 260,000 dollars to perform. As a refugee, I don’t have that kind of money, and therefore, had no choice but to use computer as a means to compose. The software help us to acquire all acoustic sounds, ethnic sounds and electronic sounds. One may deem these sounds are artificial, but it could not be done otherwise since I have only limited monetary resources. Had I been a musician in a prosperous country with strong cultures, I would have had an symphony orchestra concert at my disposal.

And yet, Pham Duy and Duy Cuong’s commitment to exploring new forms of media technology is more than just financial resourcefulness. Pham Duy and Duy Cuong each said to me several times that they regard computer and sound technology as a means to cross over generational interests and concerns, to “bridge the gap” between the Vietnamese who grew up in Vietnam and those who grew up in the United States. Duy Cuong said that they rely on the computer and its associated technologies both “to preserve the musics of the past and to bring that music into the present.” Clearly, Pham Duy and Duy Cuong don’t use technology only as a means to an end; rather, they reflect on its cultural role in their community and make the most of its possibilities.

Pham Duy’s CD-ROM in the Vietnamese American Community

Looking at a product alone provides a limited picture. By itself, a product is not a technoculture; it comes to life only when it is used and thus embedded in particular practices; any technological object—a cassette, a musical instrument, a computer, etc.—only has meaning in the context of praxis. Considering any of these things as autonomous objects is in itself a cultural practice, e.g., the turn-of-the-century Sachs-Hornbostel organological scheme for classifying instruments tells one more about the German scholars trying to organize a basement full of musical instruments from all over the world than about the people who actually played the instruments. Understanding Pham Duy’s motivations and intentions in authoring the CD-ROM is certainly part of the picture but not all of it, and yet getting at reception is one of the most difficult and untheorized areas of ethnomusicology and performance studies (and it is completely overemphasized in marketing and advertising, both dominated by the late-twentieth-century aesthetic of overdetermination). John Mowitt is one of few critical theorists to focus on electronic reproduction and reception. He argues that focusing solely on production obscures the shaping force of reception (1987: 177):

If recording organizes the experience of reception by conditioning its present scale and establishing its qualitative norms for musicians and listeners alike, then the conditions of reception actually precede the moment of production. It is not, therefore, sufficient merely to state that considerations of reception influence musical production and thus deserve attention in musical analysis. Rather, the social analysis of musical experience has to take account of the radical priority of reception, and thus it must shift its focus away from a notion of agency that, privileging the moment of production, preserves the autonomy of the subject.

In the case of Pham Duy’s CD-ROM, the conditions and “radical priority” of reception are a diasporic Vietnamese community that believes it will return home and that is dedicated to reproducing the place itself and its metonymic relationship to cultural memory. Mowitt points out that in electronic reproduction, “the production and reception of all music is mediated by the same reproductive technologies” (1987: 194), i.e., electronic media carries with it political implications for control and channeling. The Kicon website and Pham Duy’s CD-ROM are clearly dedicated to the cultural maintenance of memory and are predicated on the expectation of similar priorities on the part of its audience, but that audience produces, in turn, Pham Duy and the Vietnamese web specialists who create mediated community. Mowitt argues for an “emancipatory dialectic of contemporary music reception” (1987: 174) that acknowledges the institutions that generate social memory and experience, describing a “socio-technological basis of memory” that has certain political ramifications; I suspect that this is taken for granted by the Vietnamese American cultural producers who work so passionately to reestablish community through technoculture.

In June 1995, just after the CD-ROM was released, Pham Duy invited me to come watch him present the album to the members of a Vietnamese music club in Little Saigon, less than a mile from his home. Completely in his element, Pham Duy talked to some fifty Vietnamese American audience members ranging in age from their twenties to fifties and including an approximately equal number of men and women; he addressed the process of putting this well-known work onto CD-ROM and then the room was darkened and a computer projector threw the monitor image of the CD-ROM program onto a large screen at the front of the room. Pham Duy sat in the front row, watching the screen and commenting through a microphone on what went by; Bui Minh Cuong, the engineer from Coloa, Inc., who designed the CD-ROM, sat at the computer and silently ran through the contents of the album, clicking the mouse in response to Pham Duy’s narration and commentary. The presentation took about forty-five minutes; when the lights were turned on, Pham Duy and Bui Minh Cuong went up to the front of the room and took questions from the audience.

The emcee first apologized for problems with the sound blaster on the computer used during the presentation (not the engineer’s own) and then said, “Please encourage Pham Duy’s efforts to help the Vietnamese community by buying the CD-ROM or encouraging others to buy it.” The first question from an audience member was exactly what I would have asked: “Why do you think technology is important for the Vietnamese?” Pham Duy answered at length:

I consider myself the first [Vietnamese] person to have made a CD. I did it for the community—I didn’t mean to sell thousands or millions of them. Now the different music stores, Lang Van, Lang Vo, and others have come out with a million CDs and have squashed us! But at this point I can only count five people who work on CD-ROM—it’s not too crowded.

Walking on my way to exercise, I say to a friend, “Please come see my CD-ROM this afternoon!” [He answers,] “What is a CD-ROM?” Which means he doesn’t understand what a CD-ROM is. I am really happy that I jumped in, and I guarantee that I will open up a new way for many other people to jump in, too. I think that we only need to have lived in America for two years to adopt this technology. If we lived in America for twenty years and didn’t adopt this technology, we would do better to have stayed home. If we have technology going hand-in-hand with art then we can do much better, for the sake of Vietnam. I really hope Vietnam will change quickly so I can give a hand to Vietnamese culture.

The audience member and Pham Duy each assumed that technology had a specific importance for Vietnamese Americans beyond its obvious uses and focused instead on the driving question for Vietnamese Americans of a certain generation, i.e., how can Vietnamese culture be “helped,” maintained, preserved, defined in an American context? All other questions move out from this central concern. A doctor in the audience then stood up and offered his thoughts on the relationship between technology and the Vietnamese community:

I don’t have any question, but I do have some suggestions I want to share with everyone today. About five days ago I read a San Francisco magazine article saying that we Americans should use CD-ROMs for educating the young, so I feel very happy and proud to see that Pham Duy has put his music on CD-ROM…. Pham Duy, you have filled a need of the Vietnamese people living in America with the new technology. This could be a great and effective benefit to the Vietnamese people living in America. The young will follow your CDs and thus understand Vietnamese culture and the history of our country. We will all understand it because he uses both the Vietnamese and English languages [in his CD-ROM]. In my family, I can see that the computer is not only for adults and students but also for my grandchildren, only six, seven, eight years old, who already play on the computer every day. I only use my grandchildren as an example, but I think that the thing this musician [Pham Duy] has given us will continue for a thousand generations. The musician [Pham Duy] deserves our congratulations and respect.

The doctor thus acknowledged that CD-ROM technology has the potential to bridge the perceived generation gap between those brought up in Vietnam and those not; he celebrated its new importance for its role in cultural maintenance. Pham Duy modestly acknowledged the doctor’s praise by saying that half the congratulations should go to the engineer, Bui Minh Cuong, because he wouldn’t have known what to do without him. “This is a very helpful marriage between technology and art,” he said.

The emcee then said that they were out of time but noted that Pham Duy would be going on tour to Washington, D.C., and to Paris the next week to promote his CD-ROM, and he urged the audience to learn the new technology, to “jump in.” He then announced contests for writing awards in the local newspapers and an upcoming meeting of the club to introduce the Internet. He said, “What is the Internet and how can we access its programs? What are the dangers and how can we avoid them—the good of the Internet and the bad of the Internet? A group of Vietnamese engineers will discuss this and will show us how to get on to the Internet. This is one of the fastest modern ways to make contact and to send information—it is super fast.” He then thanked everyone for coming and the session ended.

Brief though it was, I found this exchange fascinating for its assumptions: technology was not celebrated simply for what it was or for its perceived modernity. Rather, everyone tacitly agreed that it was a new way to uphold and to preserve cultural information and memory. Whereas fear of cultural gray-out is a common middle-class American intellectual response to the expanded role of technology in everyday life, the music club audience was closely focused on the specific ways emergent technologies could help them to cohere as a community with ties to another culture. Also, they did not discuss CD-ROM technology in relation to matters of cultural assimilation: if anything, a marked confidence in maintained Vietnamese identity characterized the discussion.

Places and Non-Places in the Vietnamese Diaspora

I am fascinated on two counts by French anthropologist Marc Augé’s little book (really an extended essay) Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (1995). Written in the style used by so many French intellectuals—intimate, poetic, yet assertive—the book outlines the growing presence of “non-places” in our lives, that is, supermarkets, airports, hotels, cash machines, and freeways, or sitting in front of a television set or computer, all described by Augé as having no “organic” social life. He sees these non-places as a consequence of “supermodernity,” his term for the cultural logic behind late capitalist phenomena. Non-places are distinguished by Augé from “space” (1995: 77–78): “If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place. The hypothesis advanced here is that supermodernity produces non-places, meaning spaces which are not themselves anthropological places and which … do not integrate the earlier places: instead these are listed, classified, promoted to the status of ‘places of memory,’ and are assigned to a circumscribed and specific position.”

Augé writes that supermodernity is the “obverse” of postmodernity (1995: 30)—the other side of the same coin—and that excess of time and space is its defining characteristic, an “overabundance of events” brought about, among other things, by technology run amuck in a postindustrial world. Augé is particularly bothered by the way that other social spaces are brought into the home by television, creating a “spatial overabundance” (31) of overlapping places. He has a great nostalgia for what he calls “anthropological place” even while recognizing that it is an “invention” and a “fantasy” (75–76). He provides an intellectual history of place and space (referencing de Certeau, among others) and notes that he would “include in the notion of anthropological place the possibility of the journeys made in it, the discourses uttered in it, and the language characterizing it” (81). He argues that space, however, is defined by movement and travel, even (85–86) “a double movement: the traveller’s movement, of course, but also a parallel movement of the landscapes which he catches only in partial glimpses, a series of snapshots piled hurriedly into his memory and, literally, recomposed in the account he gives of them, the sequencing of slides in the commentary he imposes on his entourage when he returns.” Spaces are thus empty, solitary, ahistorical, shifting. Augé is most of all concerned with spaces that become non-places in the context of supermodernity: over and over again, he evokes “transport, transit, commerce, and leisure” (94) as the effects of supermodernity and the forces that create certain spaces/non-places and shape an individual’s relationship to them. The user of a non-place or a traveler through it enters into a certain contractual agreement to allow his or her identity to be defined by the space. Augé sums up these conditions by asserting that “the space of non-place creates neither singular identity nor relations; only solitude, and similitude” (103).

I have gone into Augé’s argument at some length because it offers a compelling model for misunderstanding Pham Duy’s CD-ROM. I can’t help but try to read Pham Duy’s activities through Augé’s concerns, as I am fairly certain that Augé would consider Pham Duy’s CD-ROM a non-place, presumably read in solitude and driven by supermodernity. Augé says that in non-places “there is no room for history unless it has been transformed into an element of spectacle, usually in allusive texts” (103– 104), and thus invites us to regard the CD-ROM as a collection of spectacular, nostalgic texts, inviting a certain gaze but offering little more than similitude. Augé does not address the politics of class or movement and travel: his travelers are unmarked, and his example par excellence (at the beginning of the book) is a French businessman going to his cash machine, driving along the freeway to the airport, and boarding a plane. Middle-class travel through supermodern non-places is thus presented as emblematic, but, at this point in my essay, its problematic relationship to the forced, traumatic migration of Vietnamese refugees is obvious and troubling. Pham Duy is both forthcoming and reflexive about the place of travel and movement in his life. I asked him why several of his major works are song cycles about roads and epic travel (Voyage through the Motherland, Song of the Refugee’s Road, etc.), and he answered, “I am the old man wandering, the old man on the road. It is my destiny and the destiny of my people—always moving. The Jews and the Chinese went everywhere, but slowly, gradually. The Vietnamese went all at once—in one day, one hour! Viet originally meant to cross over—like an obstacle—to overcome. So this is the essence of the Vietnamese spirit. Now Viet just means ‘people,’ though its real meaning is ‘the people who overcome, who cross over.’ ” Pham Duy thus theorizes the place of movement in his own work as well as in his culture, putting it in the context of historical comparison and the memory implicit in language. Augé renders difference invisible by flattening out travel and thus establishes universalized non-places by unthoughtfully making the businessman’s plane flight and the refugee’s journey equivalent. In a conversation with James Clifford, Stuart Hall refers to “the fashionable postmodern notion of nomadology” (Clifford 1997: 44), the theorized uprooting of peoples from fixed time and place. By inference, mass communications technologies are part of the apparatus of supermodernity that create non-places.

Music technocultures are considered “real” social spaces by many Vietnamese Americans. Arguing the matter in the abstract, or without an explicit consideration of history and cultural politics, has, it seems to me, little point; I have chosen here to work at a closely local level—some might feel overly local—but I think this is the only way to get at the social workings of any music technoculture. Pham Duy’s work could be seen as a concerted attempt to create not only places but “places of memory” that fill a particular role in Vietnamese American culture. Clifford writes (1997: 250), “People whose sense of identity is centrally defined by collective histories of displacement and violent loss cannot be ‘cured’ by merging into a new national community.” Pham Duy’s places of memory stand between four different sites: a nation-state that he and many overseas Vietnamese refuse to recognize (the Socialist Republic of Vietnam), the united but colonized nation of pre-1954 Vietnam, the divided Vietnam of 1954–75, and the diasporic communities of overseas Vietnamese in the United States, Australia, and France. Vietnam does not stay put as a spatial or temporal location in any political terms, and landfall in the United States or any other overseas Vietnamese community hasn’t resolved the problems of place for many Vietnamese, especially those of Pham Duy’s generation. Little Saigon is almost certainly a different place for the Vietnamese American undergraduates now taking my classes than it is for Pham Duy. Clifford has eloquently argued for treating travel as a major condition of the twentieth century rather than an anomaly in relation to historicized places (1997: 3):

During the course of [my] work, travel emerged as an increasingly complex range of experiences: practices of crossing and interaction that troubled the localism of many common assumptions about culture. In these assumptions authentic social existence is, or should be, centered in circumscribed places—like the gardens where the word “culture” derived its European meanings. Dwelling was understood to be the local ground of collective life, travel a supplement; roots always precede routes. But what would happen, I began to ask, if travel were untethered, seen as a complex and pervasive spectrum of human experiences? Practices of displacement might emerge as constitutive of cultural meanings rather than as their simple transfer or extension…. Virtually everywhere one looks, the processes of human movement and encounter are long-established and complex. Cultural centers, discrete regions and territories, do not exist prior to contacts, but are sustained through them, appropriating and disciplining the restless movement of people and things.

But even as I feel that I understand something better about the Vietnamese predicament by reading Clifford, I must acknowledge that this explanation would be unacceptable to Pham Duy and many overseas Vietnamese. The route to the United States would be readily traded in if possible; the route of the Mandarin Road constituted Pham Duy’s understanding of Vietnam as a place; the route chosen by a reader through the CD-ROM is understood to communicate that dedication to place. The technomusical artifact is thus metaphorical for so much, all at once, that it forces us to confront the supermodernity of the angry refugee.

Until recently, Vietnam was a non-place for overseas Vietnamese: it was not to be returned to, politically beyond reach, and morally repugnant. However, the resumption of diplomatic relations between Vietnam and the United States has changed everything. Vietnamese Americans can and do return to Vietnam, though most only for visits. Duy Cuong recently spent over two years in Vietnam (1995–97), sampling the sounds of Vietnamese instruments to bring back to Little Saigon for digital editing and reproduction;11 these sounds are an integral part of his latest project with his father, Minh Hoa Kieu (The Tale of Kieu), a song cycle telling the quintessentially Vietnamese story of the young woman Kieu. Pham Duy could not return to Vietnam for twenty-five years; indeed, the present government persists in banning his songs despite their continued circulation through pirate cassettes, often brought by overseas Vietnamese, and his visit in 1999 was controversial. Duy Cuong painstakingly weaves the sampled sounds of Vietnamese musicians into the song cycle, over and under the voices of the Vietnamese American singers who sing the main parts. The resulting pastiche could be seen as a postmodern collapsing of past and present, Here and There, but Duy Cuong’s purpose is to establish something authentically and unequivocally Vietnamese; as his father said, Duy Cuong is a “fabricateur,” but this implies not artifice but rather the technowizard who maintains the past and its places by pulling them into the present.

The proliferation of technologies and their affordability and accessibility to consumers of any sort, including immigrant communities, poses a challenge to theories of mass mediation and of travel. Localized uses of technology in Orange County are tied into a diasporic community that has increasingly strong ties to its origin country as economic relations open up again.12 We must be able to move theoretically from Pham Duy’s study and kitchen table to Little Saigon’s shops and TV stations, to Vietnamese American communities in other parts of the United States, to Paris, and indeed to Vietnam itself. This transnationalization of the local is far from coincidental—it is central to Pham Duy’s sense of purpose. This producer and his product encourage us to theorize the movement of technology, power, and agency through different registers of place.13

Notes

1. Pronounced “Fum Tzuuee.”

2. I use the term “Vietnamese American” throughout this essay in an attempt to stand outside the terminological identity politics of Vietnamese outside Vietnam. Some prefer to be called “overseas Vietnamese,” or Viet Kieu, “Vietnamese citizens residing abroad.”

3. The editors address these matters in great depth and detail in the introduction to this volume.

4. Though not incorporated as a township, the area is recognized by a highway sign reading “Little Saigon” near the exit off Route 22 in Orange County.

5. See Lull and Wallis 1992 for a discussion of the presence of popular music in the Vietnamese American community in San Jose, California.

6. As Pham Duy describes it, his songs about the personal sufferings and tragedies of the common Vietnamese people led to his parting ways with the Viet Minh. In his autobiography (1995: 40), he writes, “I had sung about the glory, now I sang about the tragedy—to the stern disapproval of the Viet Minh leaders who saw these songs as negative and potentially damaging to the spirit of the Resistance. I was let known of their disapproval in subtle but no uncertain terms, to which I simply did not agree, and did not even care. It was not my desire to be moulded [sic] into a war-glorifying propaganda machine…. My unyielding attitude had put me at odds with the Viet Minh leaders and would see me leaving the Resistance movement not long after.”

7. Since the 1950s, a further development along similar lines has emerged from the Vietnamese conservatory system, called nhac dan toc cai bien, “modernized traditional music.” Its blending of Vietnamese musics with European art music and Western pop is discussed in Arana 1994.

8. This is a form of music drama with historical relationships to Chinese opera and to other Southeast Asian forms of music drama.

9. All quotations from Pham Duy are from interviews I had with him at his home in 1995, 1996, and 1998.

10. The CD-ROM is available for $29.95 from Coloa, Inc., which can be contacted at PO Box 32313, San Jose, CA 95132; <email nxbcoloa@aol.com>; website <http://members.aol.com/nxbcoloa/page1.htm.>

11. Duy Cuong’s wife, Phoebe Pham, was sent to Vietnam by the advertising company that employs her. They lived in Hanoi from June 1995 until December 1997, and Duy Cuong set up a studio using the computer he brought from home in the United States. He sampled over eighty different Vietnamese instruments and singing styles, asking musicians to play single pitches as well as entire pieces. He recorded them on a professional DAT recorder and then edited them on the computer, taking out the sounds of street noise. He told me that he kept in the additional sounds that make the samples sound “human,” e.g., a flute player taking a breath; he even edited this back in so that the sample wouldn’t sound “too electronic,” as he put it. He has no plans to copyright or to package the samples, saying, “They’re all here [on my computer], and that’s good enough.” He emphasized that many of the musicians were old and hard to find and thus feels that his archive of samples represents a record of traditional Vietnamese musics that would be hard to match.

12. U.S. trade sanctions against Vietnam were lifted in 1994 and had begun significantly to change the Vietnamese American music scene in Orange County by 1999–2000. Popular music imported from Vietnam raised contentious issues for Vietnamese Americans. Young people flocked to it, while the older generation regarded it as an arm of the Communist government; local radio stations largely refused to play it, even though it sold very well in stores. Imported CDs cost as little as $2, whereas those locally produced were $8–12. Local companies found they couldn’t compete: whereas about thirty Little Saigon record companies dominated the diasporic Vietnamese market for many years (reaching a peak in 1995), eight companies had closed by 2000 and more were in trouble. This chapter thus depicts an ethnographic present and a historical moment that has already passed. See Marosi 2000 for more.

13. I am not a specialist in Vietnamese culture, so I am thankful for the help and advice I found along the way. Pham Duy was extraordinarily generous and patient, spending long hours over numerous interviews explaining his work to me; my thanks also to his son, Duy Cuong, for a fascinating tour of their home studios and to Duy Cuong’s wife, Phoebe Pham, for help with translation. My student Duc Van Nguyen selflessly provided a detailed translation of the question-and-answer period described above. Jason Gibbs kindly shared his work on Vietnamese popular song history and provided detailed feedback on this essay. I have learned much from Adelaida Reyes’s compassionate work on Vietnamese music in diaspora. As always, René T. A. Lysloff provided comments and feedback that made all the difference.

References

Arana, Miranda. 1994. “Modernized Vietnamese Music and Its Impact on Musical Sensibilities.” Nhac Viet: The Journal of Vietnamese Music 3 (1 and 2): 91–110.

Augé, Marc. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Trans. John Howe. London and New York: Verso.

Castelo-Branco, Salwa el-Shawan. 1987. “Some Aspects of the Cassette Industry in Egypt.” The World of Music 29 (2): 32–45.

Catlin, Amy. 1985. “Harmonizing the Generations of Hmong Musical Performance.” Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology 7: 83–97.

———. 1992. “Homo Cantens: Why Hmong Sing during Interactive Courtship Rituals.” In Text, Context, and Performance in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, ed. Amy Catlin. Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology 9: 43–60. Los Angeles: Department of Ethnomusicology, UCLA.

Clifford, James. 1997. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Gibbs, Jason. 1997. “Reform and Tradition in Early Vietnamese Popular Song.” Nhac Viet: The Journal of Vietnamese Music 6: 5–33.

———. 1998. “Nhac Tien Chien: The Origins of Vietnamese Popular Song.” Destination Vietnam, <http://www.destinationvietnam.com/dv/dv23/dv23e.htm>.

Greene, Paul. 1995. “Cassettes in Culture: Emotion, Politics, and Performance in Rural Tamil Nadu.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

———. 1999. “Sound Engineering in a Tamil Village: Playing Audio Cassettes as Devotional Performance.” Ethnomusicology 43 (3): 459–89.

Hay, James, Lawrence Grossberg, and Ellen Wartella. 1996. “Introduction,” in The Audience and Its Landscape, ed. by Hay, Grossberg, and Wartella, 1–5. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Jones, Steve. 1990. “The Cassette Underground.” Popular Music and Society 14 (1): 75–84.

Kottak, Conrad Phillip. 1990. Prime-Time Society: An Anthropological Analysis of Television and Culture. Belmont, California: Wadsworth, Inc.

Lull, James and Roger Wallis. 1992. “The Beat of West Vietnam.” In Popular Music and Communication, 2nd ed., 207–236. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Lum, Casey Man Kong. 1996. In Search of a Voice: Karaoke and the Construction of Identity in Chinese America. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Manuel, Peter. 1993. Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marosi, Richard. 2000. “Vietnam’s Musical Invasion.” Los Angeles Times, August 8, pp. A1 and A16.

Mowitt, John. 1987. “The Sound of Music in the Era of its Electronic Reproducibility.” In Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance, and Reception, ed. Richard Leppert and Susan McClary, 173–97. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pace, Richard. 1993. “First-time Televiewing in Amazonia: Television Acculturation in Gurupa, Brazil.” Ethnology 32 (2): 187–205.

Penley, Constance, and Andrew Ross. 1991. “Introduction.” In Technoculture, viii–xvii. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pham Duy. 1975. Musics of Vietnam. Edited by Dale R. Whiteside. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

———. 1995. History in My Heart/Lich Su’ Trong Tim. Edited by Nguyen Mong Thuong. Unpublished manuscript.

Reyes, Adelaida. 1999a. Songs of the Caged, Songs of the Free: Music and the Vietnamese Refugee Experience. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

———. 1999b. “From Urban Area to Refugee Camp: How One Thing Leads to Another.” Ethnomusicology 43 (2): 201–20.

Rodgers, Susan. 1986. “Batak Tape Cassette Kinship: Constructing Kinship through the Indonesian National Mass Media.” American Ethnologist 13 (1): 23–42.

Slobin, Mark. 1982. Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immigrants. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Sutton, R. Anderson. 1985. “Commercial Cassette Recordings of Traditional Music in Java: Implications for Performers and Scholars.” The World of Music 27 (3): 23–45.

Tran, Tini. 1998. “Local Link Gives Scattered Vietnamese a Meeting Place.” Los Angeles Times, June 1, pp. A1, A16.

Wallis, Roger and Krister Malm. 1984. Big Sounds from Small Peoples: The Music Industry in Small Countries. London: Constable.

Wong, Deborah. 1989/1990. “Thai Cassettes and Their Covers: Two Case Histories.” Asian Music 21 (1): 78–104. (Reprinted in Asian Popular Culture, ed. John Lent. Boulder: Westview Press, 1995.)

———. 1994. “I Want the Microphone: Mass Mediation and Agency in Asian American Popular Music.” The Drama Review [T143], 38 (2): 152–67.