Before the Deluge

The Technoculture of Song-Sheet Publishing Viewed from Late-Nineteenth-Century Galveston

Leslie C. Gay, Jr.

In 1884 the Galveston music publisher Thos. Goggan & Bro. published, as part of this company’s routine activities, a rather ordinary song sheet, entitled “Longing,” by a scarcely known German American composer, a Mr. A. Jungmann.1 Sometime after this song’s publication, one copy of this song sheet—a copy found today in the archives of Galveston’s Rosenberg Library—became a point of social interaction, for one notable aspect of this song sheet is a hastily penned inscription to “Lou Bonnot comp[liment]s of Mr. Reitmeyer.” Like the song’s composer, not much is known about these persons. Starting with the 1888–89 Galveston City Directory and continuing in directories well into the twentieth century, Mr. William F. Reitmeyer is listed as a piano tuner working for the Thos. Goggan & Bro. music store, a necessary complement to Goggan’s music-publishing business. And Miss Louise Bonnot appears in the city directory of 1891–92, identified as a music teacher. This inscription, this trace of human interaction, and these bits of information about the lives of a young piano tuner and a music teacher suggest relationships and motivations about which I can only guess—an exchange of friendship or courtship, or just business savvy—nonetheless, possible relationships to which I shall return.

This inscription draws these two people together around the song sheet and the piano. The scenario, and the communications it implies, anchors to specific technological adaptations and cultural institutions. Its communication emerges from the technoculture of this time and place, carried in part on the technologies of writing, printing, and publishing, like the more obvious high-tech symbol of the late nineteenth century—the railroad—rides on the technologies of “gears and girders.”2 My focus here is on how song-sheet publishing, viewed from late-nineteenth-century Galveston, constitutes a technocultural community, loosely bound by specific technological adaptations, uses, and meanings. I am particularly concerned with how those within this community were supported, while those outside, namely newly arrived immigrants and long-established minority groups in Galveston, were excluded. In this sense, song sheets and the technologies they encompass helped to incorporate an emerging transregional public culture and point to tensions among ethnic and class-based social groups, working to accommodate some while resistant to others.

My research on this technoculture follows studies of technologies that encompass more than examination of an isolated technological artifact. Rather, my approach necessarily includes associated cultural practices—a shift “from the instrument to the drama in which existing [social] groups perpetually negotiate power, authority, representation, and knowledge,” as Carolyn Marvin puts it.3 Most studies concerned with the nexus of music, culture, and technology exist, however, within a frame defined almost exclusively by the historical span of electronic media technologies. This study looks across this conceptual barrier.

Late-nineteenth-century Galveston serves as an especially well-suited locale for research into these issues. Located in a transitional zone, Galveston existed as a liminal place—geographically and historically—where predominately English- and Spanish-speaking cultures came together, where the memory of immigration and settlement was strong for many of its citizens, even as the notion of “frontier” began to wane, and at a time when technologies, among other factors, were transforming the United States. Yet, although it existed before the deluge of the omnipresent electronic media that so define our existence today, this Galveston shows cultural practices and social organizations surprisingly familiar to many of us.

A Technocultural Institution

Throughout the nineteenth century, sheet-music publishing and availability expanded dramatically in the United States. In the first quarter of the century some 10,000 pieces of music were published by U.S. commercial publishers.4 By 1866 the Boston publisher Oliver Ditson alone had a catalog of 33,000 pieces of music, and within ten years, Russell Sanjek estimates, there were some 200,000 published compositions for piano and piano and voice.5 Furthermore, with the growth of transcontinental railroads after the U.S. Civil War, in addition to long-established shipping routes, publishers could deliver sheet music cheaply and efficiently to individuals and other music businesses throughout the country.6 Equally important, and corresponding to the growth of sheet-music publications, are increases in the sheer number of music-publishing houses. Beginning with a handful of active businesses after the American Revolution, music publishing expanded to at least sixty-five firms by 1869.7 Significantly, rather than becoming centralized among a few publishers in New York City—as in the twentieth century’s Tin Pan Alley—music publishing in the previous century became important in cities small and large throughout the country, from Boston to Cincinnati and San Francisco, and from Chicago to St. Louis and New Orleans.8 A house publication of Chicago’s Lyon & Healy makes the extent of music publishing clear: “Here [in Illinois] … every town of 20,000 inhabitants has its music publisher, and some have catalogues of a hundred or two.”9 Music publishing, not surprisingly then, was a part of the everyday activities of some folks in Galveston, Texas.

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the city of Galveston gained prominence as the most important trading and banking center in Texas. As a seaport on the Gulf of Mexico it rivaled New Orleans.10 Throughout this period it was a major city of the state, consistently greater in population than the older Spanish-Mexican San Antonio and nineteenth-century urban rivals of Austin, Houston, Dallas, and Waco.11 Moreover, Galveston’s shipping lines to New Orleans, Mobile, Havana, New York, Boston, and Europe made it not only a center of trade but also one of immigration, especially German immigration.

As a component of this commercial activity and immigration, Thomas and John Goggan, a pair of immigrants from County Kerry, Ireland, established Galveston’s first music store, Thos. Goggan & Bro. Thomas set up shop in Galveston in 1866, just after the U.S. Civil War, and his brother joined him in the business in 1868. Although Thomas’s route to Galveston remains unknown, John immigrated first to New York in 1862 and then on to Cincinnati, where he learned music printing and retailing with the William C. Peters Piano Company. Emulating the model of Peters’s business, Goggan, nearly since its inception as a music-instrument retailer, also published song sheets. The brothers’ store, located first in the Pix Building on 22nd and Post Office Streets, moved in 1877 to its own three-story building at the corner of 22nd and Market Streets, both of which were near the center of Galveston’s commercial activities.13 In both locations they sold pianos, organs, and other musical instruments besides song sheets, instrumental music, and pedagogical piano pieces. The store acquired stock from U.S. instrument makers; notably, they also imported instruments directly from European manufacturers. The Galveston store sold its first Chickering piano in 1866 (also the first sold in Texas), and early on Thos. Goggan and Bro. became the sole selling agent for Steinway pianos in Texas.14

The Goggans expanded greatly in the area. They engaged at least twenty employees, who included salespersons but also technicians, such as three piano tuners, one of whom was Mr. Reitmeyer. At John Goggan’s death in 1908 (Thomas died in 1903 while on a visit to Ireland), in addition to the Galveston main office, five branch offices were located throughout the state, in Dallas, San Antonio, Waco, Austin, and Houston. Other Galveston business persons partly credited the brothers’ success to their aggressive advertising in newspapers and circulars, and to the use of traveling salespersons working throughout the state, with the arrival of the railroads in Texas. Even as Goggan’s music publishing in Galveston ended in 1930, the Houston branch continued as a music jobber through the early 1940s, and a few of the branch stores continued their retail business through the mid-twentieth century.15

This synopsis of Goggan’s history points to institutional affinities with other song-sheet publishers. Research on publisher histories in the United States portrays important similarities and connections among publishers and links America’s publishers with London models.16 Like Goggan, most publishers began through the combination of a small-scale engraver or printer and someone with music interests, such as piano manufacturing, musical instrument sales, music performance, or all three. Generally, from an urban location favoring trade, publishers established themselves as, or emerged from, a music shop offering music instruction and the sale of instruments along with song sheets, instrumental dance music for the piano, and instruction manuals. Frequently, music publishers began sheet-music sales by first offering music of distant publishers. Those publishers that flourished developed close and long-standing working relationships with numerous selling agents and publishers elsewhere in the geographic region and beyond to tender their materials.17

These similarities among song publishers illustrate elements of a recognizable transregional technoculture. Corresponding operation histories point to shared technological adaptations, an aspect that helps unify song-sheet publications. Similar engraving and printing techniques inevitably dispersed a familiar “look.” Moreover, business relationships among publishers strengthened these connections. Not only was it common for publishers to acquire one another’s music plates outright and thus reproduce exact copies of song sheets, publishers also shared publications through selling-agent agreements among distant publishers across a wide geographic area.18 Hence, many song sheets published by Galveston’s Thos. Goggan & Bro. appear in other publishers’ catalogs—including Boston’s Oliver Ditson and Company and Peters in Cincinnati. The reverse also occurred.

I choose to highlight the technological basis of this cultural institution with the designation “technoculture.” However, such predictable social organizations and operations of music publishers could also identify a unified “industry,” what Howard Becker labels an “art world.”19 Such worlds, in Becker’s sense, each with its own well-defined and often restrictive modes of working, have been associated with the large entertainment and “culture” industries of this century, not those of the past, and often have been assumed to be related to, if not wholly products of, twentieth-century capitalist models of production. Goggan’s business concerns also compare to other aspects of late-twentieth-century market capitalism. The transectorial interdependence between song-sheet publishing and music instrument retailing remains today as a familiar alliance between music publishers, manufacturers, and recorded-music retailers. Yet, its very familiarity obscures the importance of such interdependencies to Goggan and other song-sheet publishers within this emerging technoculture in the United States. Paul Théberge argues that recent innovations in musical instrument and recording technologies depend upon a technical interdependence among often-disparate industry firms, multinational corporations, and manufacturing sectors.20 Rather than a new phenomenon, however, broadly based transectorial interdependencies long ago linked printing and instrument-manufacturing technologies with marketing and retailing. Moreover, just as recent innovations in communications technologies, such as computer user groups, have helped shape communities of music consumers,21 newly expanded transportation routes after the U.S. Civil War, especially the railroad, accelerated print communications and helped draw some nineteenth-century Galvestonians into the public culture of song sheets and song performance.

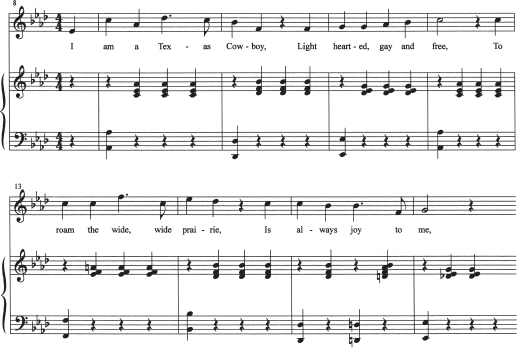

Publishers of this technoculture also disperse similar musical styles. Within the United States, song sheets published in the latter half of the nineteenth century are surprisingly homogeneous; with few exceptions, they are similar in form and content. Goggan’s song publications illustrate familiar song types of this period, including waltz songs, Scotch and Irish songs, and minstrel or “coon” songs.22 Thomas M. Bowers’s “Trilby and Little Billie,” published by Goggan in 1895 and subtitled “Waltz Song and Chorus,” illustrates conventions that mark this song type: triple meter, solo strophic song with chorus, clearly framed tonality in a major key with a few diatonic harmonies, and reserved and regular melodic phrases with formulaic nonharhomic tones. Moreover, its limited vocal range, straightforward text setting of a somewhat exotic, sentimental text, and predominant rhythmic pattern consisting mostly of strings of dotted-half notes suggest this song was meant for home consumption (see fig. 1, mm. 9–25).

Fig. 1. “Trilby and Little Billie”

While the use of duple meter and, at times, more complex rhythms distinguished the other common song types from waltz songs, the bulk of all Goggan’s song publications show the simplified structural, harmonic, and melodic practices that, according to Charles Hamm, most U.S. song composers used from the middle of the century on to accommodate “an even wider range of listeners and performers.”23 The very straightforwardness of this song, its lack of overtly technical or extravagant passages, makes it a music for amateur performance. The shared stylistic similarities of these songs across a wide geography suggest links among communities of performers and listeners, consumers of this public culture. Thus, despite existing well outside the major music-publishing centers of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, Goggan participated in this public culture, selling music that largely conforms to that published in other distant cities. Shared song-sheet styles, coupled with predictable organizations and operations of publishers across the country, identify a unified technocultural institution.

The exchange between Mr. Reitmeyer and Miss Bonnot, the piano tuner and the music teacher, emerges from the technological space defined in part by the song sheet and the piano. In nineteenth-century Galveston, as elsewhere, the performance of song sheets achieved a level of activity and musicianship that sustained publishers, piano technicians, and music teachers. Moreover, with the sales of song sheets and the requisite pianos, music publishers and educators encouraged music performance in the home, especially among women. These technologies thus imply activities, socially and musically performative, that illuminate aspects of this space, from broad practices of publishers and teachers to notions of self and place for women.

In this context, Mr. Reitmeyer’s gift to Miss Bonnot could have been intended as an act of courtship, an exchange that references the relationship among domestic life, women, and the piano. Mary Burgan argues that for women in nineteenth-century England the piano functioned as “an emblem of social status,” providing “a gauge of a woman’s training in the required accomplishments of genteel society.”24 An 1856 publication in New York suggests a similar association in the United States. The etiquette book’s title literally tells it all: The lady’s guide to perfect gentility in manners, dress and conversation, in the family, in company, at the piano forte, the table, in the street, and in gentlemen’s society…. 25 Skilled performance at the piano for women thus demonstrated the virtue of “gentility,” a model of “cultivated” personal excellence and social display.26 Moreover, along with other furnishings in the parlors of nineteenth-century homes, the piano and the song sheet helped define a space of “culture” and “comfort” for women and their families, says Katherine Grier,27 one that further illustrates a cosmopolitanism, marking associations and knowledge beyond the local even while contained by this domestic space.

Perhaps, too, Mr. Reitmeyer’s gift of the song sheet gently encouraged romance, a means to woo Miss Bonnot, one function of popular song familiar to us in this century. Some scholars, notably Donald Horton, have argued that popular song in the twentieth century offers “conventional conversational language” for dating and courtship, a ready-made script to support such social interactions.28 This was also the case in the late nineteenth century. For example, Russell Sanjek explains how the composer and Harlem Renaissance writer James Weldon Johnson shifted his emphasis from musical theater to the larger popular song market, writing songs that “young men took along when courting, to be played by their girls, giving both sexes an opportunity to vent their sentiments decorously.”29

The gift equally could have been simple business savvy by Mr. Reitmeyer, encouraging or maintaining a relationship between a local piano teacher and his firm. Music education, piano sales, and music publishing were increasingly important careers or business concerns at the time, and they were substantially linked. The period from the Civil War through the Great Depression was a golden age for the piano business in the United States. In 1866, the founding year for Thos. Goggan & Bro., piano sales reached $15 million, accounting for some 25,000 new instruments. And in the 1900 census, the first time such information becomes available, music careers employed 92,000 Americans, Moreover, piano instruction established itself as an economically rewarding career at this time. In 1887 the Music Teachers National Association (founded 1876) reports that its members taught a half-million piano pupils. Connections between music publishers and teachers were tight, with the most successful piano teachers as active salespersons of music sheets, which they purchased at a 50 percent discount from most firms. Somewhat controversial is the fact that teachers realized almost half as much income from their music sales as from teaching, even as publishers profited 500 to 600 percent on each music sheet.30

For Thos. Goggan & Bro. as well as other piano retailers and song-sheet publishers, women certainly were important customers, both as teachers and general consumers who helped shape the firm’s activities. Théberge notes that the marketing of pianos to women points to the home as “the center of family life and locus of individual consumption.”31 This connection finds correlates in other aspects of women’s lives: for instance, music periodicals of this period at times overlap music with other household technologies, as seen in one periodical from 1880, the Musical and Sewing Machine Gazette.32 Thus, it is not surprising that as tastes included other household technologies, the offerings at Goggan’s retail stores changed to match them. Eventually, the stores sold all sorts of home appliances besides music wares, everything from sewing machines and toasters to gas ranges and freezers. Equally significant, after establishing the first radio station on Galveston Island in the early 1920s, Goggan also sold radios, reflecting shifts in home music consumption away from song sheets and pianos.

Looking at Boundaries

The circumscribed spectrum of musical styles seen in song sheets, beyond illustrating close ties among publishers, also reflects relationships between publishers and audience communities. Consideration of these complex relationships requires questions about how audience boundaries are marked and maintained: how do the publications help define this public culture, in what ways are they directed toward and away from specific communities, and what communities are represented or not represented? Goggan’s publications reveal the publisher and the local song-sheet audience working to define itself, to draw some Galveston citizens in while restricting others. The gift from Mr. Reitmeyer to Miss Bonnot exists within a social area of shifting and blurred boundaries. Technological aspects of song sheets, from musical and lyrical content to literacy (both English and music literacy), and the socioeconomic requirements to obtain such technologies define and support this community while excluding others.

Minstrel songs, what Hamm calls “the first distinctly American genre,”33 began to outline the boundaries of this technocultural community. Minstrelsy emerged in the United States from those public spaces such as markets, historic and geographic points where in the tangent of European and African cultures “there was an eagerness to combine, share, join, draw from opposites, play on opposition,” W. T. Lhamon shows us in his book, Raising Cain.34 As a theatrical performance, minstrelsy became a public expression of racial relationships between European and African Americans. “Minstrelsy,” writes Eric Lott, “brought to public form racialized elements of thought and feeling, tone and impulse, residing at the very edge of semantic availability, which Americans only dimly realized they felt, let alone understood.”35 This relationship was largely an expression of white middle-class men toward African Americans and thus points to a particular junction of gender, ethnicity, and class. As published song sheets—that is, without their multidimensional theatrical context—minstrel songs, and the later form “coon” songs, are less clearly gendered male but remain focused at intersections of ethnicity and class.

Minstrel songs published in Galveston and elsewhere make explicit a boundary between black and white. Music and song performance within minstrel shows, especially in early minstrelsy, has been characterized by its connections to oral traditions—based loosely on melodic and rhythmic gestures derived from African American dance and song with heterophonic renditions with banjo, fiddle, tambourine, and bones accompaniment.36 The difficult translation of this theatrical musical style to song sheets reflects these roots in oral traditions. In an analysis by Katherine Reed-Maxwell, early minstrel publications, often not attributed to any composer, illustrate African American characteristics of asymmetrical rhythmic and melodic groupings structured by call-and-response patterns. Later minstrel-song publications, those clearly meant for parlor performance with named, if not well known, composers, show more conventional groupings of notated, printed European American music—more rationalized rhythms and uniform melodic repetition with “correct” harmonic progressions within a formalized song structure.37

Fig. 2. “Paint All de Little Black Sinners White”

Fred Lyons’s “Paint All de Little Black Sinners White,” published by Thos. Goggan & Bro. in 1887, exhibits these print-music characteristics (see fig. 2, mm. 9–16). The song features a simple accompaniment with rigid rhythmic patterns, each beat of the quadruple meter squarely reinforced. Harmonically, its skillful modulation from the key of D minor to F major on each melodic phrase allows for a unique harmonic progression. Its use of syncopation and dotted rhythms in the vocal melody gives a rhythmic bounce, distinct from most waltz and other parlor songs, which, however, could just as easily derive from European American oral traditions as African American ones. Strophic verses with chorus, framed by a piano introduction and piano “dance” ending section, organize this piece. In sum, Lyons’s piece bears few musical similarities to earlier minstrel publications and the more oral-based forms common to the minstrel stage.

Moreover, through its cover iconography of racist caricatures and lyrics in minstrel dialect, Lyons’s more-than-ironic song portrays a transformation of African American “sinners” into what I can only interpret as “good white citizens.” The lyrics begin:

Oh! My troubles gone and my heart is feeling gay,

Dey gwine to paint all de little black sinners.

We’ll have a happy time, and we’ll celebrate the day …

The first verse continues after some repetition:

We’ll all mix together no matter where we go,

When dey paint all de colored people white.38

The cover-page illustration, also shared with another Lyons song, “Dem Chickens Roost Too High,” reflects the scenario of the lyrics by showing a railyard in which African Americans are unloaded from one train, literally given a paint job, and placed on another train (identified as the “T. G. & Bro.” line; see fig. 3).

Such textual and visual aspects surely reference class and ethnic divisions—especially the way in which white workers used the minstrel show to distinguish themselves from blacks.39 These divisions eventually mutated the “Jim Crow” stage character into a gloss for the apartheid-like segregation codified by law in the late-nineteenth-century United States. But the “redemptive” aspects of Lyons’s text, the ultimate resolution made by transforming these caricatured persons into white citizens, coupled with its lack of overtly derogatory lyrics, made it acceptable for performance in the home while maintaining social divisions. All these aspects distinguish minstrel song sheets from risqué theatrical performances and moved minstrel song sheets away from traditional African American expressive forms. This boundary, however, was neither rock solid nor invariably fixed.

Throughout the last decades of the nineteenth century, African Americans began to appear regularly and in significant numbers on the minstrel stage and even to rival in popularity their white counterparts. As Robert Toll has shown in his book, Blacking Up, minstrelsy was an avenue for mobility to African Americans not available elsewhere, a domain in which black men found their “first chance to become entertainers.”40 Indeed, Fred Lyons was such an entertainer, a noted, if not well known, banjo player and comedian, and a song-sheet composer.41 Minstrelsy also offered to African Americans avenues of moral, political, and economic discourse, what Dale Cockrell views as an agitating social “noise.” Such discourse from the stage played a role in the fight against slavery.42 Yet by mid-century minstrelsy had largely lost this capacity, according to some researchers. “Dialect blackface,” writes Cockrell, “had become more a form of gross mockery.”43

Fig. 3. “Paint All de Little Black Sinners White,” cover illustration. Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Department of Special Collections, the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, The Johns Hopkins University.

The widely exposed and standardized form and content of the minstrel stage, especially the derogatory stock characters, imposed a racist archetype upon all who chose to perform there, black or white. Such an archetype effectively delineated minstrel performance as a product primarily of white America and for white America, regardless of its performers. As song-sheet publications, minstrel songs perpetuated this segregation and marked a boundary that, like the minstrel stage, African Americans did not cross easily or without some self-consciousness.

There were, of course, African Americans in Galveston presumably involved with a range of other musics. The city directories from mid-century on list a minimum of two “colored” churches, implying a significant population of African Americans. Yet Goggan apparently directed no publications toward this audience; their musical interests existed outside this publisher’s purview. For instance, there are no examples of black religious music, what had become known as “Negro spirituals,” in Goggan’s catalog. Within the nation, too, few publishers dealt with such music, mostly connected with the abolitionist movement.44 This disregard certainly was due in part to the currents of increasing segregation throughout the country. Goggan, however, was also responding to commercial interests based on demographics: this audience was largely illiterate.

Exact knowledge of how socioeconomic and technological restraints effected literacy rates of African Americans in this period of Galveston’s history is difficult to estimate. Through 1870 general literacy was higher in the nonslave states than in the South. Within the slave states, literacy was greater for white families holding slaves, that is, for wealthier families. Thus, throughout much of the southern United States, good reading skills were uncommon for working-class people, black and white, especially in the more remote, rural areas. In urban areas with the highest concentrations of commercial and manufacturing activity, however, literacy was consistently higher. In this light, Soltow and Stevens show areas of the Texas Gulf coast near Galveston with some of the highest illiteracy rates in the country.45 Literacy in Galveston was probably higher, especially among wealthier whites. Between the 1870 and 1900 censuses, white illiteracy in the country as a whole had declined from 11.5 to 6.2 percent. For African Americans, while illiteracy remained high, the change was dramatic, from 81.4 to 44.5 percent.46 If we make the uneasy assumption that music literacy correlates with general literacy, it is probable that only a few African Americans in Galveston could claim such “higher order” literacy skills as music reading, restricting many from song-sheet performance.

The technologies of literacy and language demarcate this community for the publisher Thos. Goggan & Bro. in Galveston. Texas’s heritage as a former Mexican state, Coahuila y Tejas through 1836, coupled with the number of Spanish surnames found in Galveston city directories between 1861 and 1881, imply that a segment of its population, probably a large one, spoke Spanish rather than English. That Goggan’s publications center on an English-language audience, with little regard for Spanish speakers, ties to deep prejudices of this public culture in Texas. Texas-Mexican populations in the brief period of the Texas Republic endured discrimination from their white neighbors that included the atrocities of forced migration, land dispossession, and random violence.47 Texas Mexicans fared little better than African Americans during the period of increasing segregation after the U.S. Civil War, as Arnoldo De León makes clear: “Mexicans were held in no higher esteem than blacks and Indians…. Jim Crow signs read ‘for Mexicans’ instead of ‘for Negroes’ in South Texas. Though the idea was no longer vocalized as often as before the Civil War, it was understood that only minor differences separated ‘greasers’ from ‘redskins’ and ‘niggers.’ ”48 Yet Goggan did publish a series of piano pieces called Choicest Mexican Music, and one song with Spanish lyrics, “La Golondrina.”49 And, while the publications are decidedly directed to an English-language audience, not a Spanish one, such publications suggest relations and accommodations between whites and Texas Mexicans more complex than the strict segregation that Jim Crow signs and racist terms denote.

“La Golondrina,” Goggan’s one Spanish-language song, was published for an English-speaking audience to advertise the Mexican National Railroad and its connections within Texas. All text on its cover and back-page advertisement is in English, with the Spanish lyrics given in English translation. While this advertisement primarily shows transportation ties between Mexico and Texas, it also emphasizes other boundaries and connections between the United States and Mexico: first in a map on the back page, then in its cover illustration of the Mexican and U.S. flags, and finally with a statement comparing the song’s Mexican popularity with the popularity of “Home, Sweet Home” in the United States (see figs. 4 and 5).

Goggan’s instrumental series, Choicest Mexican Music, is no less directed toward an English-language audience. Mexican songs of this series are virtually stripped of Spanish-language referents, arranged for piano only, with titles often given in English translation with the original Spanish displayed secondarily, if at all. Such song-sheet publications support the case that relations between whites and Texas Mexicans in the late nineteenth century were often inconsistent and contradictory, especially when they concerned “Castilian” and landed elites.50 Song publications reveal complex ethnic prejudices that distanced working-class Texas Mexicans while acknowledging elites, even promoting their commercial concerns.

German immigrants in Galveston are no better represented in the music publications of Thos. Goggan & Bro. than Texas Mexicans, although German Americans crossed over as song composers—including our Mr. Jungmann. German immigrants (mostly farmers and craftspeople) and first- and second-generation German Americans were a significant segment of Galveston’s population; by the mid-1850s, from one-third to one-half of Galveston’s population was German. Local publications often cited these immigrants for their musicianship. The historian Earl Fornell notes that German immigrants’ “proficiency in the use of musical instruments … inspired both admiration and chagrin among” non-German craftspeople in Galveston; German wind bands also were regular and important contributors to civic celebrations.51 Moreover, German singing societies were active in the numerous German communities of the state, formally organized and concertizing statewide as the Texas Sängerbund by 1853.52 Yet, although Goggan’s city directory advertisement list German accordions for sale in the music shop, no song-sheet publications are in German or refer to Germans at all.

Fig. 4. “La Golondrina,” cover illustration. Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Department of Special Collections, the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, The Johns Hopkins University.

Fig. 5. “La Golondrina,” back illustration. Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Department of Special Collections, the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, The Johns Hopkins University.

As stated already, many working-class Galvestonians likely found their lack of musical literacy a deterrent to participating in this technoculture. The portrayal of rural working-class Texans in Goggan’s song sheets further suggests a border that contains a genteel urban class while also excluding farm- and ranch-hands. One published song about Texas cowboys, rather than embracing the experiences of rural life, presents a removed, romanticized picture of rural Texas. Comparisons between published “cow-boy” songs and those collected at the turn of this century from working ranch-hands show few similarities.

“The Texas Cow-Boy,” by Mrs. Robt. Thomson,53 corresponds more to “cowboy” songs published elsewhere in the United States54 than to songs sung by working cowboys such as those collected by folklorist John Lomax.55 The awkward use of “cowboy” idioms, marked by Thomson in the text with quotations, show the song’s composer, singers, and audiences as anything but ranch-hands. The song only gingerly associates with cow-boys and cowboy life, not allowing them to get too close. Thomson’s first and last verses with chorus follow:

I am a Texas cowboy,

Light hearted, gay and free,

To roam the wide, wide prairie,

Is always joy to me,

My trusty little pony,

Is my compaion true;

O’er plain, thro’ woods and river,

He’s sure to “pull me thro.”

Chorus:

I am a jolly cowboy,

From Texas now I hail,

Give me my “quirt” and pony,

I’m ready for the “trail”;

I love the rolling prairie,

We’re free from care and strife,

Behind a herd of “long-horns”

I’ll journey all my life.

And when in Kansas City,

The “Boss” he pays us up,

We loaf around a few days,

Then have a parting cup.

We bid farewell to city,

From noisy marts we come

Right back to dear old Texas,

The cow-boy’s native home.56

Such gentility is lacking in Jack Thorp’s song, “Little Joe, The Wrangler,” collected by John Lomax in his Cowboy Songs.57 With its basis on an actual event, “Little Joe, The Wrangler” locates itself in a specific place—a camp on the Red River—with a real person, Little Joe.58 Compare Thomson’s text with Thorp’s (verses 8 through 11).

Little Joe the wrangler was called out with the rest

And scarcely had the kid got to the herd

When the cattle they stampeded; like a hail storm, long they flew

And all of us were riding for the lead.

’Tween the streaks of lightnin’ we could see a horse far out ahead

’Twas little Joe the wrangler in the lead;

He was ridin’ “old Blue Rocket” with his slicker ’bove his head

Trying to check the leaders in their speed.

At last we got them milling and kinder quieted down

And the extra guard back to the camp did go

But one of them was missin’ and we all saw at a glance

’Twas our little Texas stray—poor wrangler Joe.

Next morning just at sunup we found where Rocket fell

Down in a washout forty feet below

Beneath his horse mashed to a pulp his spurs had rung the knell

For our little Texas stray—poor wrangler Joe.59

Its narrative structure and the deadly reality of the tale—within a stampede, horses are powerful and dangerous tools, not cherished companions—distinguish it from Thomson’s published song.

Besides the contrast of the texts, there are other distinctions between the two cowboy songs. Thorp’s song in its earliest publication appears as lyrics only, meant to be sung to a familiar tune, “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane.”60 The tune, as published in Lomax’s collection, also shows a musical distance between the two songs, suggesting a social distance as well. Thomson’s song with its four-square meter and the tune’s consistent rhythm on the verse—which contrasts ever so slightly in the chorus with the use of dotted rhythms—bears little in common with the looser, more varying rhythms, including some syncopation—in the Lomax transcription of “Little Joe” (see fig. 6, mm. 9–16, and fig. 7, mm. 1–8). Moreover, the wide range of an octave plus a fifth of Thomson’s song, often outlining the chords of the accompaniment, and its use of a few chromatic tones, would do little to reinforce the narrative aspects of Thorp’s song. The Lomax version, with its narrow range of a sixth (an octave at one brief point), is constructed with the more limited pitch set of a hexatonic scale. Rural music of working-class life in Texas exists apart from the gentrified musical expression found within the public culture where song sheets are found.

Goggan’s publications reveal, too, a segment of this population striving to place Galveston within an emerging transregional identity of which the technologies of music publishing were part, struggling to represent Galveston not as peripheral to but as engaged with this public culture. Thus, a performance of Thomson’s “The Texas Cow-Boy,” in part because of its remoteness from working cowboys, presents Galvestonians as genteel, urban Texans, both locally knowledgeable and distantly cosmopolitan.

Other song-sheet publications also emphasize the local while connecting to cosmopolitan themes, reinforcing or transforming a civic identity for Galveston and Texas. “The Pirate Isle No More,” by W. A. Hogan and H. A. Lebermann (1889), a song written for the city’s semicentennial celebration, sensationalizes its earliest history with Spanish and French buccaneers—“once was the home of the Pirate Lafitt”—while repositioning the city as a newly arrived mercantile center—now “Texas’ proud queen of commerce.” This theme continues on its cover, shared with Eduard Holst’s “The Semi-Centennial Grand March” (1889). The illustration lauds the city’s fifty-year history of expansion through “before and after” lithographs, comparing its early existence as a seaside hamlet with a later view of Galveston’s business district. A waltz celebrating the new state capitol, the “Texas State Capitol Grand Waltz” by Leonora Rives (1888) and dedicated to Gov. L. Sullivan Ross, features a lithograph of the newly built, and here dramatically illustrated, capitol building in Austin. The architecture of the building, a rotunda flanked by opposite wings similar to the nation’s Capitol, is shown in gargantuan scale, dwarfing the carriages and pedestrians on the surrounding streets. Another Goggan publication, “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders: March—Two Step” (1898), written by L. F. Haaren for the regiment of U.S. cavalry volunteers who fought in the Spanish-American War, shows Galveston involved with an important national event along with the latest dance craze. Local interests surely influenced its publication—the regiment trained near San Antonio. However, the war signals the emergence of U.S. colonial expansion beyond its continental boundaries in the same decade as the notion of a geographic “frontier” in Texas had all but vanished, thus allowing for a more cosmopolitan Texas within an emerging public culture.

Fig. 6. “The Texas Cow-Boy”

Fig. 7. “Little Joe, the Wrangler”

Summary and Conclusion

Song-sheet publishing viewed from the perspective of Galveston’s Thos. Goggan & Bro. reveals a connected “industry” of publishers, both large and small, across the country, actively engaged in support of a technocultural community in which song sheets and pianos are important parts. This community is linked through institutions that create and support song sheets, aligning printing and instrument manufacturing technologies with transportation, marketing, and retailing.

This transregional community, moreover, accommodates those with the socioeconomic and corresponding technological wherewithal to participate while restricting those not so blessed. The song-sheet publications of Goggan, along with our piano technician Mr. Reitmeyer and our music teacher Miss Bonnot, thus exist within a social domain connecting Galveston homes and their household technologies with other music publishers and an emerging mostly white, English-speaking public culture across the United States. This technoculture deters the participation of portions of Galveston’s population through its “mechanisms”—the economic requirements to access pianos and the song sheets themselves, along with the requisite performance skills and necessary literacy, both music and English-language literacy. My analysis of Goggan’s publications suggests that for a less educated working class, and especially for immigrant and minority groups, full participation in this community was difficult. In the case of the African American population of Galveston, the explicitly racist topics and iconography of some song sheets further discouraged their participation.

In retrospect, the existence of such a technologically based public culture should surprise no one. Such social structures became more pronounced throughout the first half of the twentieth century and remain familiar, traceable still today. Song-sheet technologies, like more recent electronic ones that merge domestic spaces with a cosmopolitan world, may offer a prospect of crossing social boundaries, as the minstrel song composer Fred Lyons did, but they more often mediate among similar, like-minded folks near and far, connecting them and defining, in part, their social relationships. With their similar physical designs and unified musical styles, the technological basis of song sheets, too, seems well established,61 if less obviously high-tech as vinyl LPs or digital CDs and MP3 recordings. Like these newer technologies, the importance of song sheets and their publication, however, does not lie with the artifacts alone but, rather, with their social use. What emerges here is the way in which these technologies and access to them delineate and maintain a public culture across the United States, even for small-scale music publishers such as Goggan, in cities such as Galveston, a point that bears emphasis, lest we let our familiarity with the “nuts and bolts” obscure the social significance of such old technologies.

I am skeptical, though, of views that take technological developments and adaptations—even such seemingly fundamental technologies as language, literacy, and print—as deterministic, as “thunderclaps of history” that predictably transform human societies.62 Elsewhere I argue against such simplistic views by maintaining that relations between technologies and their cultural use are complex, with uses and meanings constructed and contested through the discourse of daily lives.63 Yet communication technologies like song sheets are implicated within the myriad ways we build social relations, make exchanges, and create meaning. The gift from Mr. Reitmeyer to Miss Bonnot, whatever else it might denote as a point of exchange, exists in this context to maintain and conserve rather than transcend and radicalize, to buffer rather than challenge the social domain disclosed by the song sheets.

Finally, most discussions of music, culture, and technology focus on technologies of the electronic media. While there are profound cultural implications with the application of electricity to communications, including musical communications, a focus mostly on the technological extremes of the late twentieth century obscures important transformations of the more recent past before widespread use of electricity. We often take electronic-communications technologies—from the radio and audiocassette to cable television and computer networks—as radically altering how we interact. Within this wash of often noisy electronic “texts,” it is easy to miss the ways in which technological adaptations of the past—notably writing and printing—have shaped social relations and remain critical to our lives. Not only in the old-fashioned newspapers or even stuffy, scholarly journals do these technologies remain significant. We find their influence in the film- and videotape-archive shows of VH1, which, no matter how hip or corny, rely upon written traditions of historiography. And we see them in the assumptions of literacy—I could add English literacy—modeled mostly on print specifications that, despite hypermedia claims, support the Internet’s World Wide Web. The importance of even seemingly mundane and modest technologies as those concerned with song-sheet publishing should not be overlooked in the glare of electronic technologies today.

Notes

My research on song sheets began with the support of the NEH and its Summer Seminar “American Song and American Culture in the Nineteenth Century,” support for which I remain grateful. I also wish to thank Anna Peebler and Shelly Henley of the Galveston & Texas History Center for their assistance with much of this research.

This publication comes from archival research at the Galveston & Texas History Center, Rosenberg Library, the Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins University, and the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

1. Scarcely known to us today, that is; according to the published opus number, this was Jungmann’s ninety-sixth composition.

2. Cecelia Tichi, Shifting Gears: Technology, Literature, Culture in Modernist America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987).

3. Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 5.

4. Russell Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years, vol. 2, From 1790 to 1909 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); Richard J. Wolfe, Early American Music Engraving and Printing: A History of Music in America from 1787 to 1825 with Commentary on Earlier and Later Practices (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980).

5. Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business, 348.

6. Ibid., 290; John F. Stover, “Railroads,” in The Reader’s Companion to American History, ed. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991), 906–910.

7. Harry Dichter and Elliott Shapiro, Early American Sheet Music: Its Lure and Its Lore, 1768–1889 (New York: R. R. Bowker, 1941); Dena J. Epstein, ed., Complete Catalogue of Sheet Music and Musical Works, 1870 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973); Wolfe, Early American Music Engraving and Printing.

8. Dichter and Shapiro, Early American Sheet Music; Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business; Wolfe, Early American Music Engraving and Printing.

9. Quotation from Epstein, ed., Complete Catalogue of Sheet Music and Musical Works, 1870, xi.

10. Earl Wesley Fornell, The Galveston Era: The Texas Crescent on the Eve of Secession (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1961); Howard Barnstone, The Galveston That Was (New York: Macmillan, 1966); David G. McComb, Galveston: A History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986).

11. E. Dana Durand, Thirteenth Census of the United States: Statistics for Texas (Washington, D.C.: Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census, 1913).

12. Indicative of both trade and immigration, Heller’s Galveston City Directory of 1874 lists consulates from Spain, Germany, England, the Netherlands, Sweden, Russia, and Denmark. See also Fornell, Galveston Era, 27, 89, 125–39.

13. The Pix Building, sometimes called the “old Tribune” building, was the home of the Galveston Tribune, a daily newspaper and a printer. It is not known, however, if any of Goggan’s song sheets came off the Tribune’s press.

14. Information on Goggan’s commercial history is compiled from The Industries of Galveston (Galveston, Tex.: Metropolitan Publishing Company, 1887); “Two Prominent Citizens Drowned: Messrs. John Goggan and John Moore Lost Their Lives at Redfish Reef,” Galveston Daily News, Sept. 7, 1908; “Gengler’s Fifteen Years Old When Goggan Opened First Texas Music Store,” Galveston Daily News, June 16, 1926, Special Gengler Edition; “Goggan Observes 65th Anniversary,” Galveston Daily News, Oct. 23, 1931, 14; Maury Darst, “Goggan Firm Wrote Songs about the Island,” Galveston Daily News, March 6, 1967.

15. Darst, “Goggan Firm Wrote Songs about the Island”; Dichter and Shapiro, Early American Sheet Music.

16. Nancy F. Carter, “Early Music Publishing in Denver,” American Music Research Journal 2 (1992): 53–67; Dichter and Shapiro, Early American Sheet Music; D. W. Krammel, “Music Publishing,” in Music Printing and Publishing, ed. D. W. Krummel and Stanley Sadie (New York: Norton, 1990), 79–132; Ernst C. Krohn, Music Publishing in the Middle Western States Before the Civil War, Detroit Studies in Music Bibliography (Detroit: Information Coordinators, 1972); Ernst C. Krohn, Music Publishing in St. Louis, ed. James R. Heintze, Bibliographies in American Music (Warren, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 1988); Peter A. Munstedt, “Kansas City Music Publishing: The First Fifty Years,” American Music 9, no. 4 (1991): 333– 83; H. Edmund Poole, “A Day at a Music Publishers: A Description of the Establishment of D’Almaine & Co.,” Journal of the Printing Historical Society 14 (1979/80): 59–81; Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business; Wolfe, Early American Music Engraving and Printing.

17. This pattern began in the United States with the establishment in 1793 of J. C. Moller and Henri Capron’s music shop in Philadelphia and their first subscription series of song sheets (Moller and Compton’s Monthly Numbers). It continued through the establishment of Benjamin Carr in Philadelphia in 1794, and James Hewitt and George Gilfert (both the same year) in New York, and culminated with the development of the music-publishing giants of the nineteenth century in the partnerships of Firth, Hall & Pond (1814–75) in New York and the company of Oliver Ditson in Boston (1835–1931) (Krummel, “Music Publishing,” 116).

18. Wolfe, Early American Music Engraving and Printing.

19. Howard Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982).

20. Paul Théberge, Any Sound You Can Imagine: Making Music/Consuming Technology (Hanover, N.H.: Wesleyan University Press [University Press of New England], 1997), 59.

21. See ibid., 131–53.

22. See Charles Hamm, Yesterdays: Popular Song in America (New York: Norton, 1983), and Hamm, Music in the New World (New York: Norton, 1983). Representative examples from Goggan’s catalog include the waltz song “Trilby and Little Billie” by Thomas M. Bowers, the Scotch song “Sweetest Lass in All the Land” by Ida Walker, and the coon song “Mr. Coon, You’se Too Black for Me” by S. H. Dudley.

23. Hamm, Yesterdays, 294.

24. Mary Burgan, “Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth-Century Fiction,” in The Lost Chord: Essays on Victorian Music, ed. Nicholas Temperly (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989), 42–67, 42.

25. Emily Thornwell, The lady’s guide to perfect gentility in manners, dress and conversation, in the family, in company, at the piano forte, the table, in the street, and in gentlemen’s society; also, a useful instructor in letter writing, toilet preparations, fancy needlework, millinery, dressmaking, care of wardrobe, the hair, teeth, hands, lips, complexion, etc. (New York: Derby and Jackson, 1856). See also Ann Douglas, The Feminization of American Culture (New York: Knopf, 1977); Leslie C. Gay Jr., “Acting Up, Talking Tech: New York Rock Musicians and Their Metaphors of Technology,” Ethnomusicology 42, no 1 (1998): 81–98; Arthur Loesser, Men, Women, and Pianos: A Social History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954); Judith Tick, “Passed Away Is the Piano Girl: Changes in American Musical Life, 1970–1900,” In Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150–1950, ed. Jane Bowers and Judith Tick (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 325–48.

26. Katherine C. Grier, “The Decline of the Memory Palace: The Parlor after 1890,” in American Home Life, 1880–1930: A Social History of Spaces and Places, ed. Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), 49–74.

27. Ibid., 53–54.

28. Donald Horton, “The Dialogue of Courtship in Popular Song,” in On Record: Rock, Pop, and the Written Word, ed. Simon Frith and Andrew Goodwin (New York: Pantheon Books, 1990), 14–26. See also Simon Frith, “Words and Music: Why Do Songs Have Words?” in Lost in Music: Culture, Style, and the Musical Event, ed. A. L. White (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987), 77–106.

29. Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business, 285.

30. Ibid., 347, 350, 370.

31. Théberge, Any Sound You Can Imagine, 99.

32. Musical and Sewing Machine Gazette (New York: Howard Rockwood, 1880).

33. Hamm, Music in the New World, 183.

34. W. T. Lhamon Jr., Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 3.

35. Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 6.

36. Dale Cockrell, Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997); Lhamon, Raising Cain; Thomas L. Riis, Just Before Jazz: Black Musical Theater in New York, 1980 to 1915 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989).

37. Kathryn Reed-Maxfield, “Emmett, Foster and Their Anonymous Colleagues: The Creators of Early Minstrel Show Songs,” paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Sonneck Society, the University of Pittsburgh, April 4, 1987, quoted in Riis, Just Before Jazz, 4–5.

38. Fred Lyons, “Paint all de little Black Sinners White” (Galveston, Tex.: Thos. Goggan & Bro., 1887).

39. David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991).

40. Robert C. Toll, Blacking Up: the Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 196.

41. Riis, Just Before Jazz, 9–10; Ike Simond, Old Slack’s Reminiscence and Pocket History of the Colored Profession from 1865 to 1891 (ca. 1891; Bowling Green, Ohio: Popular Press, Bowling Green University, 1974), 24–25.

42. Cockrell, Demons of Disorder. See also Lhamon, Raising Cain.

43. Cockrell, Demons of Disorder, 147. See also Riis, Just Before Jazz, 7. Other changes on the minstrel stage reflect the loss of subersive elements. In 1887, the publication year of Lyons’s song, Primrose and West’s Minstrels, one of the most “refined” white minstrel troupes, went on stage without blackface, signaling an important shift in popularity from blackface minstrelsy toward vaudeville-style performance (Simond, Old Slack’s Reminiscence, 48).

44. Those publishers who did publish “Negro spirituals” did so without much commercial success. Antebellum Northerners, especially abolitionists, expressed interest in the music of slaves, and accounts of African American musical expressions began to appear in periodicals and newspapers. A December 1861 edition of the New York Tribune, according to Dena Epstein, carried the first published text of a spiritual taken from runaway slaves around Hampton, Virginia (Dena J. Epstein, Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War [Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977], 45–46). Other publications followed, including a song sheet copublished by Horace Waters and Oliver Ditson entitled “The Song of the Contrabands—‘O let my People go’ ” (Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business, 270). The most extensive early publication of African American spirituals, based on music collected in the early 1860s by Lucy McKim in Port Royal, South Carolina, was Slave Songs of the United States (William Francis Allen, Slave Songs of the United States [1867; New York: Peter Smith, 1933]). Slave Songs, published by A. Simpson & Co., contains words and music of 136 “shouts” or spiritual songs. Oliver Ditson, however, declined in 1871 an offer to bring out a second edition of Slave Songs of the United States because, Russell Sanjek concludes, none of the earlier publications of black spirituals “lighted the spark of public demand” (Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business, 270–71).

45. Lee Soltow and Edward Stevens, The Rise of Literacy and the Common School in the United States: A Socioeconomic Analysis to 1870 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 148–92.

46. John K. Folger and Charles B. Nam, Education of the American Population (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1967), 113–14.

47. David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1936– 1986 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987), 27.

48. Arnoldo De León, They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821–1900 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983), 221.

49. “La Golondrina,” Thos. Goggan & Bro., Galveston, Tex., 1883.

50. Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 84.

51. Fornell, Galveston Era, 129, 133, 138.

52. Martha Fornell and Earl W. Fornell, “A Century of German Song in Texas,” The American-German Review (1957): 23–31; Lota M. Spell, “The Early German Contribution to Music in Texas,” The American-German Review 12 (1946): 8–10.

53. Mrs. Robt. Thomson, “The Texas Cow-Boy,” Thos. Goggan & Bro., Galveston, Tex., 1886.

54. For example, George Cooper and Fred A. Rothstein, “Texas Charlie,” Hitchcock’s Music Store, New York, NY, 1885.

55. John Avery Lomax, Cowboy Songs, and Other Frontier Ballads (New York: Sturgis and Walton, 1910).

56. Thomson, “The Texas Cow-Boy.”

57. Lomax, Cowboy Songs, and Other Frontier Ballads. “Little Joe” has its own literary/technological history. Jack Thorp self-published “Little Joe, the Wrangler” as part of a collection for fellow cowboys; later it was appropriated by Lomax for his collection. Thorp reports he wrote this song while on a trail ride in Higgins, Texas, 1898. See N. Howard (“Jack”) Thorp, Songs of the Cowboys, ed. Austin E. Fife, Alta S. Fife, and Naunie Gardner (1908; New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1966), 25, 29. A summary of N. Howard “Jack” Thorp’s biography appears in this edition of the collection (Thorp, Songs of the Cowboys, 3–9).

58. Lomax, Cowboy Songs, and Other Frontier Ballads.

59. Ibid., 31–32.

60. Ibid., 25, 29.

61. A number of authors have argued or suggested this shared technological basis to differing degrees and within different scholarly contexts: see, for example, Richard Crawford, The American Musical Landscape (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993); Jon W. Finson, The Voices That Are Gone: Themes in Nineteenth-Century American Popular Song (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Lester S. Levy, Grace Notes in American History: Popular Sheet Music from 1820 to 1900 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967); and, espcially, Hamm, Yesterdays.

62. Ruth Finnegan, Literacy and Orality: Studies in the Technology of Communication (New York: Basil Blackwell, 1988), 5–14.

63. Gay, “Acting Up, Talking Tech.”

References

Allen, William Francis. “Preface.” Slave Songs of the United States. New York: Peter Smith, 1933 [1857], i–xxxvi.

Barnstone, Howard. The Galveston That Was. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1966.

Becker, Howard. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

Burgan, Mary. “Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth-Century Fiction.” The Lost Chord: Essays on Victorian Music. Ed. Nicholas Temperly. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989, 42–67.

Carter, Nancy F. “Early Music Publishing in Denver.” The American Music Research Journal 2 (1992): 53–67.

Cockrell, Dale. Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Crawford, Richard. The American Musical Landscape. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Darst, Maury. “Goggan Firm Wrote Songs About the Island.” Galveston Daily News 6 March 1967.

De León, Arnoldo. They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821–1900. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983.

Dichter, Harry, and Elliott Shapiro. Early American Sheet Music: Its Lure and Its Lore 1768–1889. New York: R. R. Bowker Co., 1941.

Douglas, Ann. The Feminization of American Culture. New York: Knopf, 1977.

Durand, E. Dana. Thirteenth Census of the United States: Statistics for Texas. Washington: Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census, 1913.

Epstein, Dena J. Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

———, ed. Complete Catalogue of Sheet Music and Musical Works, 1870. New York: Da Capo Press, 1973.

Finnegan, Ruth. Literacy and Orality: Studies in the Technology of Communication. New York: Basil Blackwell, 1988.

Finson, Jon W. The Voices That Are Gone: Themes in Nineteenth-Century American Popular Song. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Folger, John K., and Charles B. Nam. Education of the American Population. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1967.

Fornell, Earl Wesley. The Galveston Era: The Texas Crescent on the Eve of Secession. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1961.

Fornell, Martha, and Earl W. Fornell. “A Century of German Song in Texas. The American–German Review. (1957): 24–31.

Frith, Simon. “Words and Music: Why Do Songs Have Words?” Lost in Music: Culture, Style, and the Musical Event. Ed. A. L. White. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987, 77–106.

Gay, Leslie C. Jr. “Acting Up, Talking Tech: New York Rock Musicians and Their Metaphors of Technology.” Ethnomusicology 42.1 (1998): 81–98.

“Gengler’s Fifteen Years Old When Goggans Opened First Texas Music Store.” Galveston Daily News, Wednesday, 16 June 1926: Special Gengler Edition. “Goggan Observes 65th Anniversary.” Galveston Daily News, Friday, 23 October 1931: 14.

Grier, Katherine C. “The Decline of the Memory Palace: The Parlor after 1890.” American Home Life, 1880–1930: A Social History of Spaces and Places. Eds. Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1992. 49–74.

Hamm, Charles. Music in the New World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983.

———. Yesterdays: Popular Song in America. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983.

Horton, Donald. “The Dialogue of Courtship in Popular Song.” On Record: Rock, Pop, and the Written Word. Eds. Simon Frith and Andrew Goodwin. New York: Pantheon Books, 1990, 14–26.

Krohn, Ernst C. Music Publishing in St. Louis. Bibliographies in American Music. Ed. James R. Heintze. Warren: Harmonie Park Press, 1988.

———. Music Publishing in the Middle Western States before the Civil War. Detroit Studies in Music Bibliography. Detroit: Information Coordinators, Inc, 1972.

Krummel, D. W. “Music Publishing.” Music Printing and Publishing. Eds. D. W. Drummel and Stanley Sadie. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1990. 79–132.

Levy, Lester S. Grace Notes in American History: Popular Sheet Music from 1820 to 1900. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967.

Lhamon, W. T., Jr. Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Loesser, Arthur. Men, Women, and Pianos: A Social History. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954.

Lomax, John Avery. Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads. New York: Sturgis & Walton Company, 1910.

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Marvin, Carolyn. When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

McComb, David G. Galveston: A History. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986.

Montejano, David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987.

Munstedt, Peter A. “Kansas City Music Publishing: The First Fifty Years.” American Music 9.4 (1991): 333–83.

Poole, H. Edmund. “A Day at a Music Publishers: A Description of the Establishment of D’Almaine & Co.” Journal of the Printing Historical Society 14 (1979/80): 59–81.

Riis, Thomas L. Just before Jazz: Black Musical Theater in New York, 1890 to 1915. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Roediger, David R. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. London: Verso, 1991.

Sanjek, Russell. American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years, vol. 2, From 1790 to 1909. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Simond, Ike. Old Slack’s Reminiscence and Pocket History of the Colored Profession from 1865 to 1891. Reprint ed. Bowling Green, Ohio: Popular Press, Bowling Green University, 1974.

Soltow, Lee, and Edward Stevens. The Rise of Literacy and the Common School in the United States: A Socioeconomic Analysis to 1870. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Spell, Lota M. “The Early German Contribution to Music in Texas.” The American-German Review 12 (1946): 8–10.

Stover, John F. “Railroads.” The Reader’s Companion to American History. Eds. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1991, 906–10.

Théberge, Paul. Any Sound You Can Imagine: Making Music/Consuming Technology. Hanover, N.H.: Wesleyan University Press/University Press of New England, 1997.

The Industries of Galveston. Galveston: Metropolitan Publishing Company, 1887.

Thornwell, Emily. The lady’s guide to perfect gentility in manners, dress and conversation, in the family, in company, at the piano forte, the table, in the street, and in gentlemen’s society; also, a useful instructor in letter writing, toilet preparations, fancy needlework, millinery, dressmaking, care of wardrobe, the hair, teeth, hands, lips, complexion, etc. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856.

Thorp, N. Howard (“Jack”). Songs of the Cowboys. Eds. Austin E. Fife, Alta S. Fife and Naunie Gardner. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1966 [1908].

Tichi, Cecelia. Shifting Gears: Technology, Literature, Culture in Modernist America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Prres, 1987.

Tick, Judith. “Passed Away Is the Piano Girl: Changes in American Musical Life, 1970–1900.” Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition 1150–1950. Eds. Jane Bowers and Judith Tick. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986, 325–48.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

“Two Prominent Citizens Drowned: Messrs. John Goggan and John Moore Lost Their Lives at Redfish Reef.” Galveston Daily News. Monday, 7 September 1908.

Wolfe, Richard J. Early American Music Engraving and Printing: A History of Music Publishing in America from 1878 to 1825 with Commentary on Earlier and Later Practices. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980.