APPENDIX 2

A MISCELLANY OF NUMBERS AND FORMS

THIS SECTION PRESENTS MORE EXAMPLES OF MATERIAL from the text including sculptural and architectural analyses, lunar notes, vesica constructions, and the golden proportion, all subjects that have been explored throughout the book. There is also additional information on the technique of diagonal geometry and ideas on the creation of harmonious forms from the vesica including pottery figures, book page layouts, and irregular shapes similar to seeds and eggs. This appendix also gives several examples of the sculptural and architectural use of the crossed-vesica constructions in several ancient cultures that we briefly mentioned in the text. The history of the gothic arch, a half-vesica shape, is considered along with some geometric arch constructions. In general, this appendix is meant to add a few practical examples to the text of the book for the use of the designer of spaces and for the philosophers and students of art and nature who are drawn to symbolic expression and to the many possibilities for creation offered by sacred geometry.

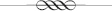

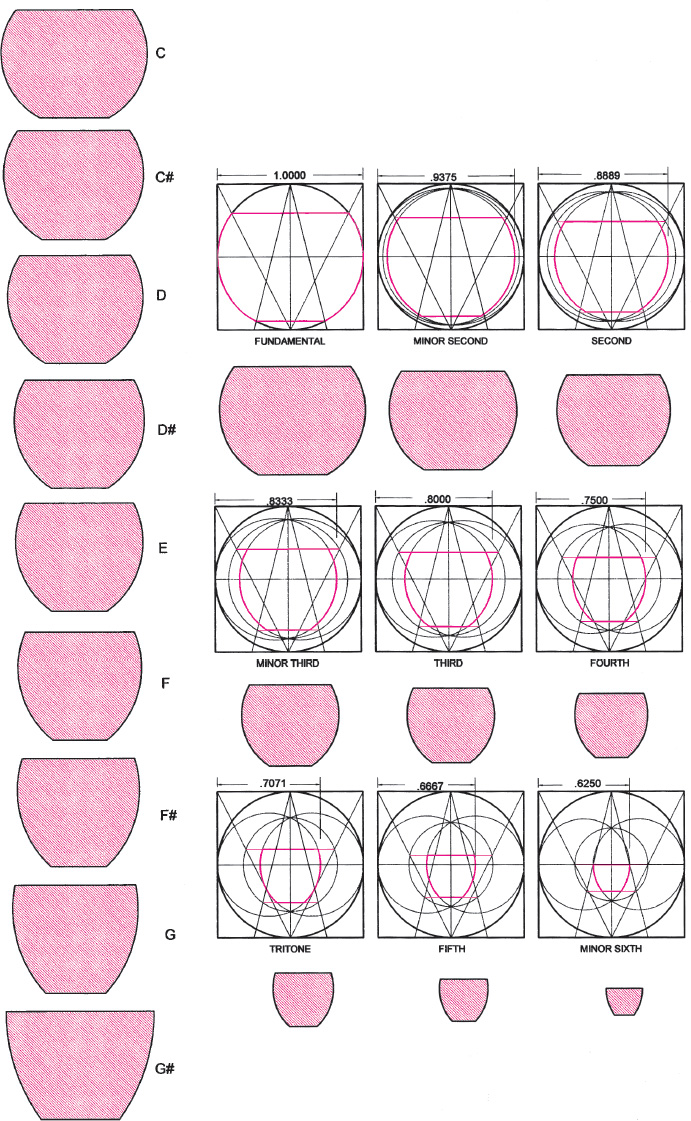

Drawing A2.1. A drawing showing the circles of the vesica construction with a table containing the property values of the vesica circles for twelve standard tones of a just-intonation scale as well as some other tones that are relevant to the geometry of vesica construction. This is a summation of the numerical aspect of the vesica construction.

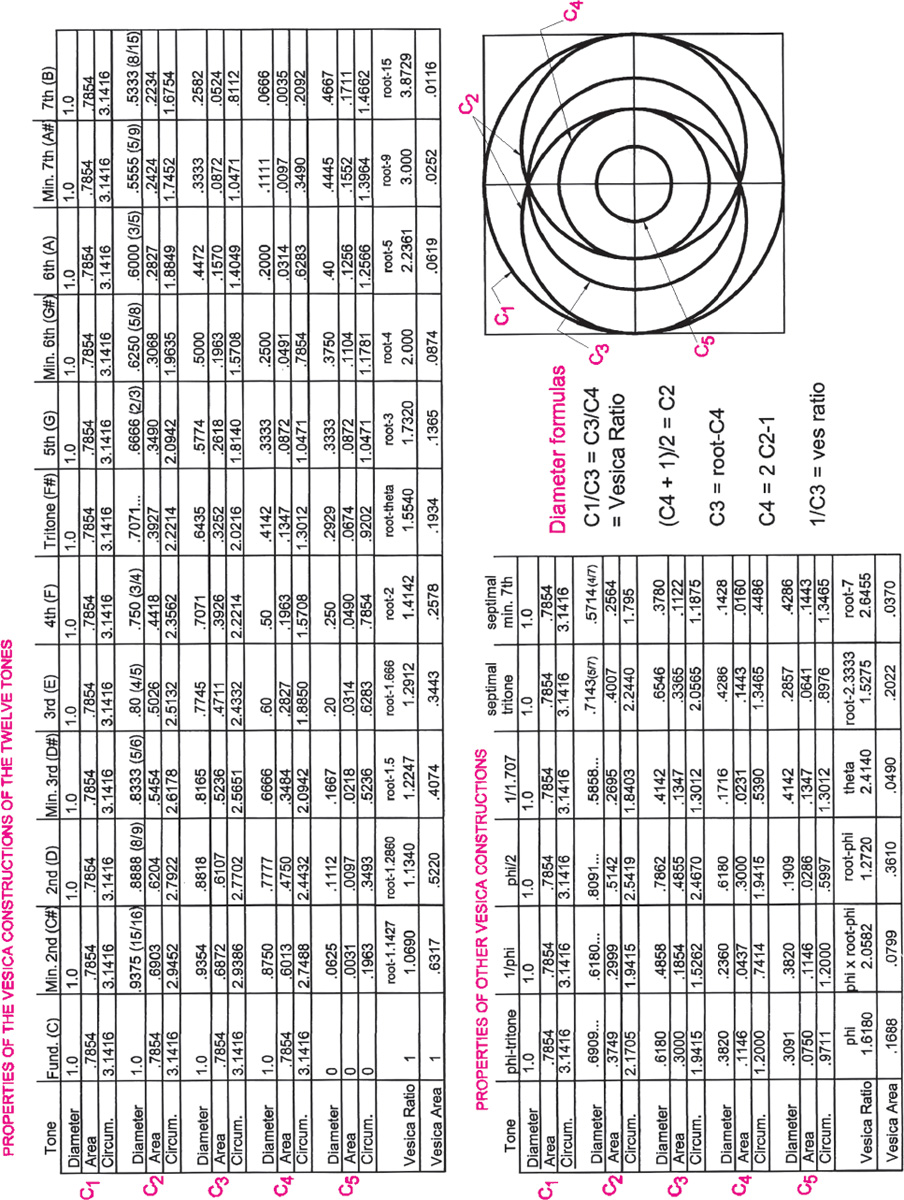

Drawing A2.2. The square possesses an unlimited wealth of rational ratios generated from the crossing of its mostly irrational diagonals. The most well-known diagonals are those of the full square, half-square, and quarter-square. The half-square diagonal is frequently used in sacred geometry as a generator of the golden rectangle and the √5 rectangle. Crossings of these principal diagonals can generate, at their crossing points, tonal ratios when the points are projected to the main string/ diameter—that is, to the horizontal diameter of the circle-in-the-square or, here, to the horizontal axis of the square. Examples of this phenomenon are demonstrated in the present drawing—a division-by-2 “diagonal weaving” where the main consonances of the scale are generated from the crossings of these basic diagonals. Furthermore, the 1/3, 1/4, 1/5, and 1/6 segments, left over from the 2/3, 3/4, 4/5 and 5/6 tonal ratios on the string/diameter, provide the lengths that we may step off on the side of a square to produce division-by-three, four, five, and six diagonal weavings from which a great many more tones may be generated. Several of these are demonstrated in the drawings A2.3, A2.4, and A2.5. Similarly, the geometrically produced 1/ϕ length when applied to the sides of a square, as in drawing A2.6, provides a generating matrix for phi-family numbers.

In this drawing the square has been divided in half both horizontally and vertically by the axes of the circle-in-the-square, and the following tones are produced from the generated diagonals 3/5 (.60), the sixth; 2/3 (.667), the fifth; 3/4 (.75), the fourth; 4/5 (.80), the third; and 5/6 (.833), the minor third.

While the diagonals are constructed without measurement we must measure the resulting string-length to determine their ratios and hence their intervals. I do this with a computer drawing program, which facilitates the exact measurement of the generated string-lengths.

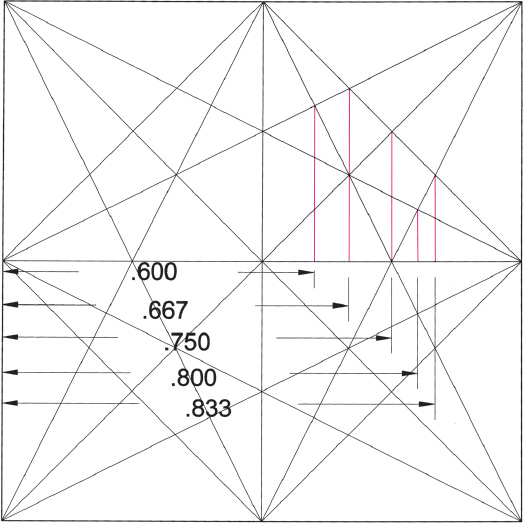

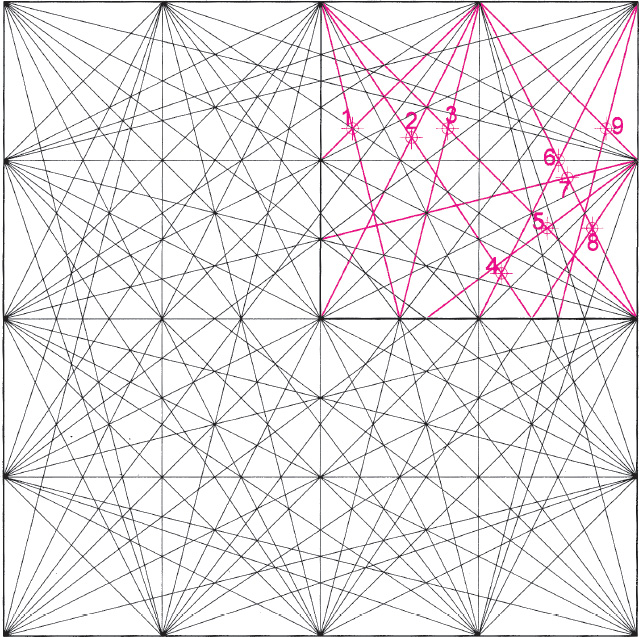

Drawing A2.3. A division-by-three diagonal weaving. The numbered points are located by the crossings and when projected (by dropping perpendiculars) onto the horizontal diameter (considered to be a musical string) produce the following tones. (1) 8/15 (.5333), just major seventh; (2) 7/13 (.5385), septimal seventh; (3) 6/11 (.5455), neutral seventh; (4) 5/9 (.5556), acute minor seventh; (5) 4/7 (.5714), just minor seventh; (6) 7/12 (.5833), septimal sixth; (7) 5/8 (.6250), just minor sixth; (8) 5/7 (.7143), septimal tritone; (9) 8/11 (.7273), undecimal flattened tritone; (10) 11/15 (.7333), undecimal augmented fourth; (11) 7/9 (.7778), septimal third; (12) 4/5 (.8000), just third; (13) 9/11 (.8182), undecimal neutral third; (14) 9/10 (.9000), minor whole tone; (15) 11/12 (.9167), undecimal neutral second.

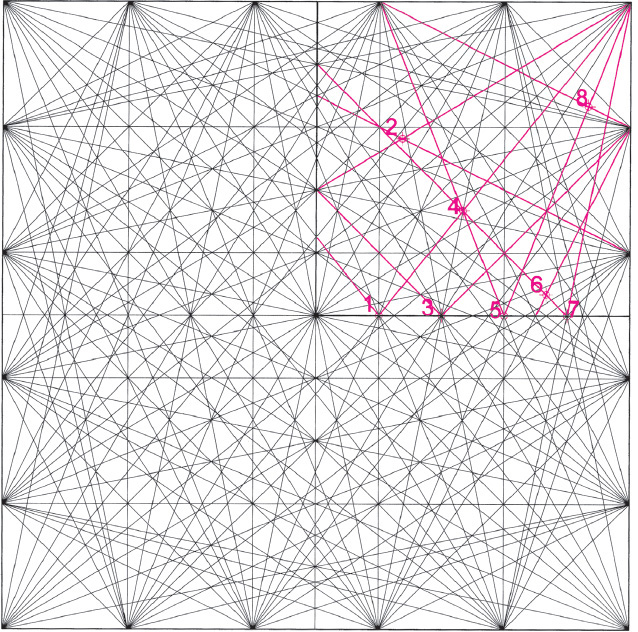

Drawing A2.4. A division-by-four diagonal weaving. (1) 11/20 (.5500), acute minor seventh; (2) 9/14 (.6429), septimal minor sixth; (3) 7/10 (.7000), Euler’s tritone; (4) 11/14 (.7857), undecimal diminished fourth; (5) 6/7 (.8571), septimal minor third; (6) 7/8 (.8750), septimal whole tone; (7) 8/9 (.8889), just whole tone; (8) 13/14 (.9286), septimal semitone; (9) 19/20 (.9500), an ancient semitone.

Drawing A2.5. A division-by-five diagonal weaving. (1) 3/5 (.6000), just major sixth; (2) 7/11 (.6364), undecimal augmented fifth; (3) 7/10 (.7000), Euler’s tritone; (4) 11/15 (.7333), undecimal augmented fourth; (5) 4/5 (.8000), just major third; (6) 13/15 (.8667), tridecimal 5/4 tone; (7) 9/10 (.9000), minor whole tone; (8) 14/15 (.9333), semitone.

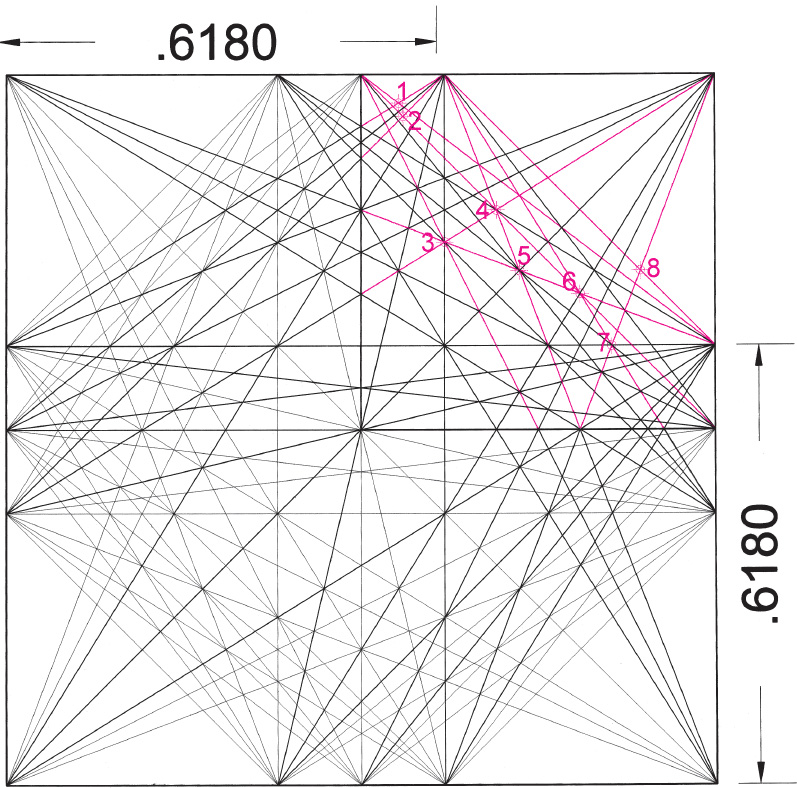

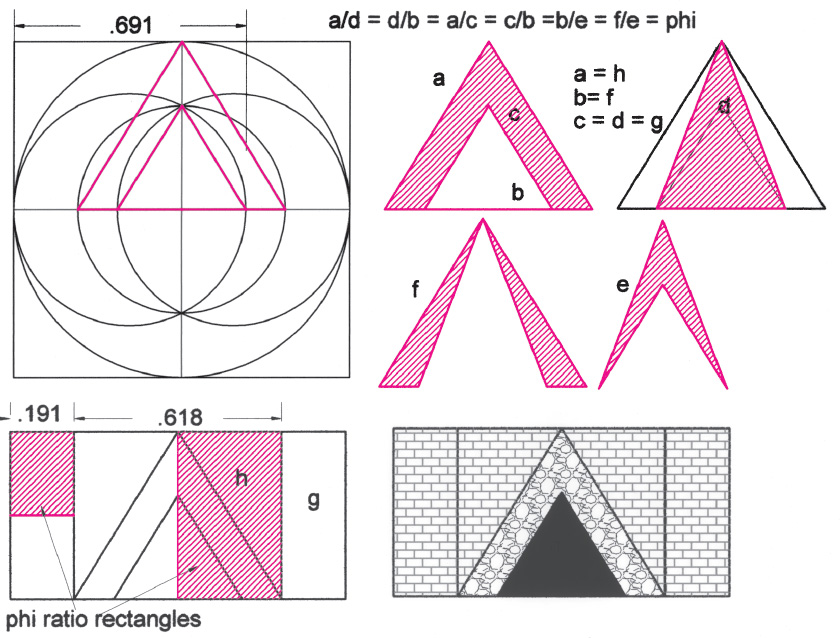

Drawing A2.6. A ϕ weaving containing several ϕ-family numbers. These reciprocals and their ratios expressed as ϕ numbers are as follows:

| Reciprocal | Ratio | |||

| (1) .5528 | 2/√5 x ϕ | |||

| (2) .559 | 4/√5 | |||

| (3) .618 | ϕ | |||

| (4) .691 | 1 + 1/√5 | |||

| (5) .7236 | 1 + 1/ϕ2 | |||

| (6) .809 | 2/ϕ | |||

| (7) .8542 | ϕ2/√5 | |||

| (8) .8944 | 2/√5 |

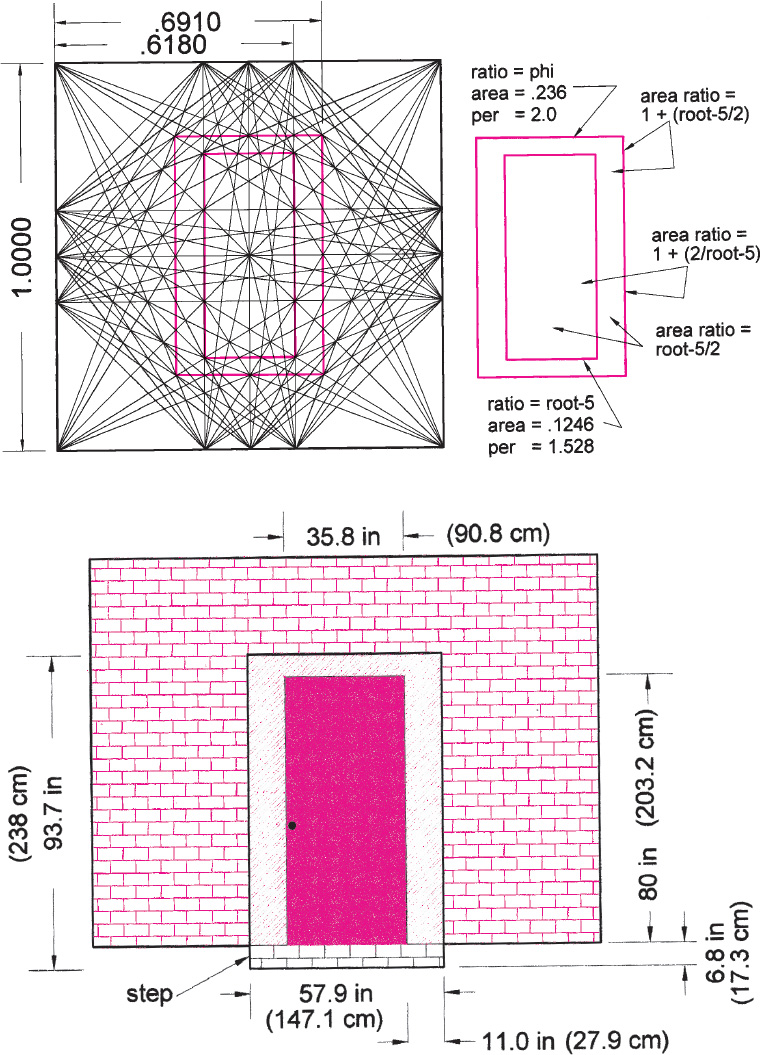

Drawing A2.7. This drawing demonstrates another use of the diagonal weavings. Here we have used the full phi weaving as our design template in order to layout a doorway. Using crossing points we have generated a golden rectangle surrounding a √5 rectangle. These closely related figures—(√5 + 1) / 2 = ϕ )—form a harmonious doorway with the √5 rectangle as the door surrounded by trim and step composed of the ϕ rectangle. Further harmonies are noted in the drawing on the right.

Drawing A2.8. On the upper left the ϕ tritone construction is made with two nested triangles. On the upper right the relations among the parts demonstrate the ϕ harmonies that pervade the structure. On the lower left we consider how the nested triangles also create ϕ harmonies in their matrix, the upper half-square. On the lower right is the completed wall opening, perhaps an entrance to a harmonic workshop.

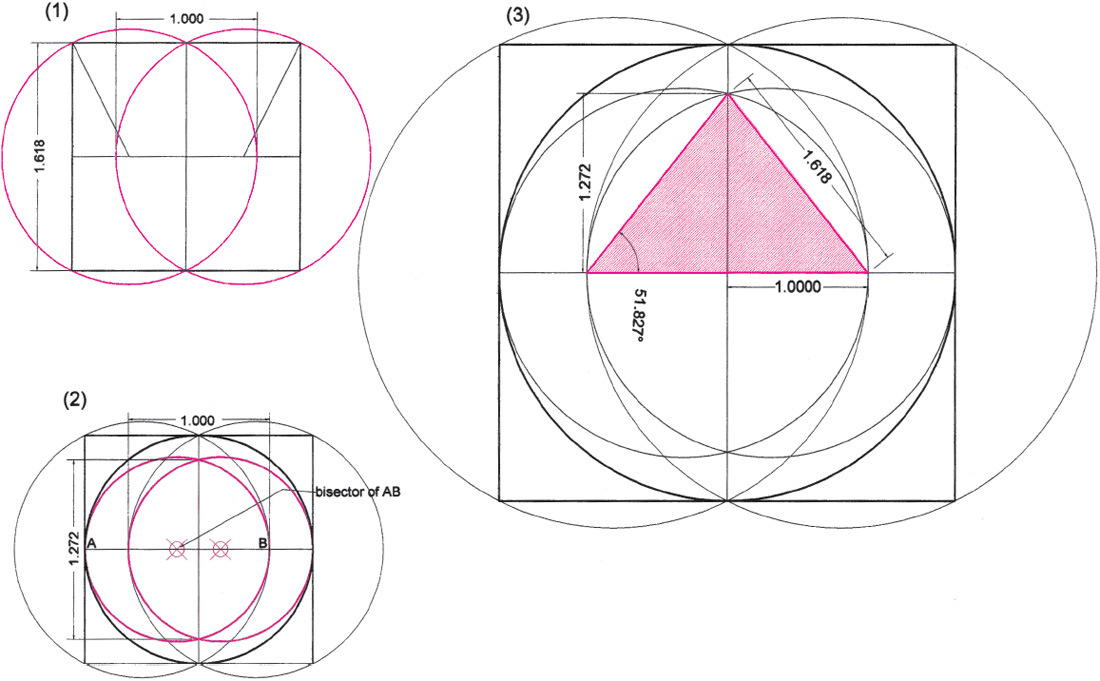

Drawing A2.9. A √ϕ vesica construction of the cross section of the Great Pyramid. Pictured in (1) is the construction of the ϕ vesica from the half-square diagonals; (2) shows the construction of the √ϕ vesica within the ϕ vesica: the bisection point of AB and its mirror point are the centers of the vesica-forming circles that generate the √ϕ vesica. In (3) the pyramid cross section is placed within the √ϕ vesica, which is surrounded by the ϕ vesica.

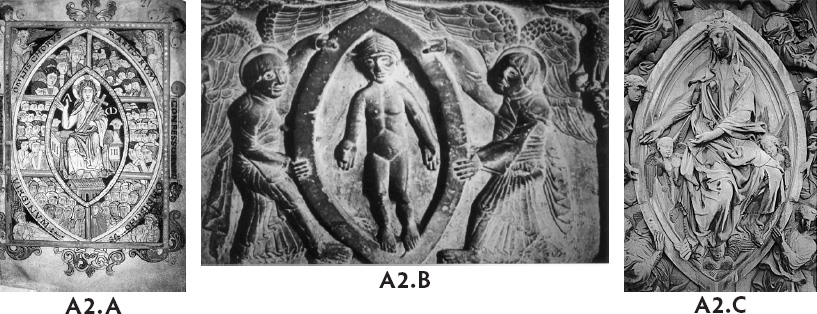

Figure A2.A–C. (A2.A) a page from the psalter of King Athelstan of England (924–940), reputed to have established the first guild of stonemasons in England; (A2.B) a carving from the tomb of Dona Sancha (ca. 1110, Jaca Monasterio de las Benedictinas) showing angels lifting the vesica-shaped soul of the deceased; (A2.C) Virgin in the vesica from the Porta della Mandorla at the cathedral of Florence.

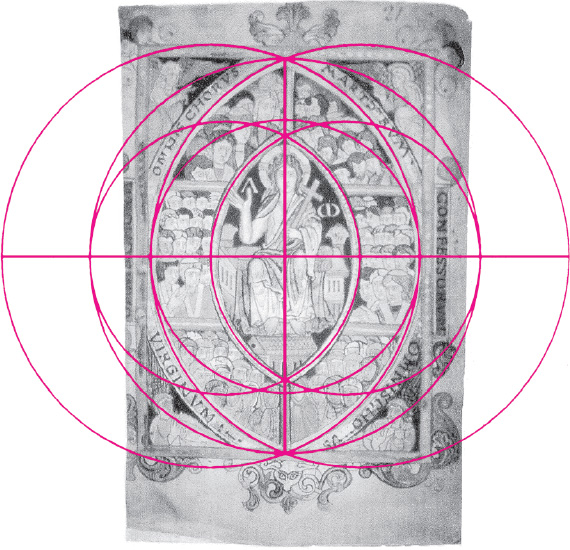

Figure A2.D

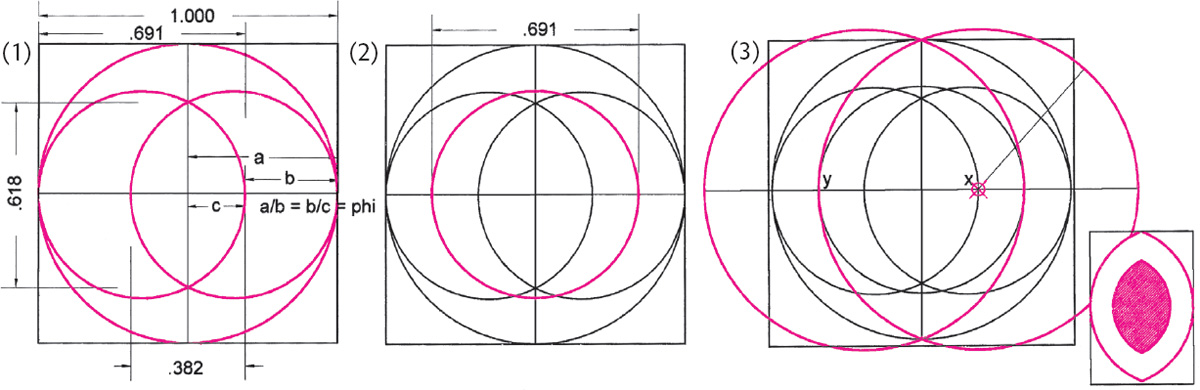

Drawing A2.10. An analysis of the construction of the Athelstan psalter (figure A2.D, above) in which, an initial ϕ section of the half square (1) is made (drawing 2.8 gives a simple geometric method of finding the .691 point) and transformed into a vesica construction with a vesica with ϕ ratio. (2) One of the vesica-forming circles is copied and centered on the construction. (3) With a radius centered on x and extending to y another circle is drawn and mirrored, giving an enclosing vesica with a ratio of 1.4472 = 1/.691.

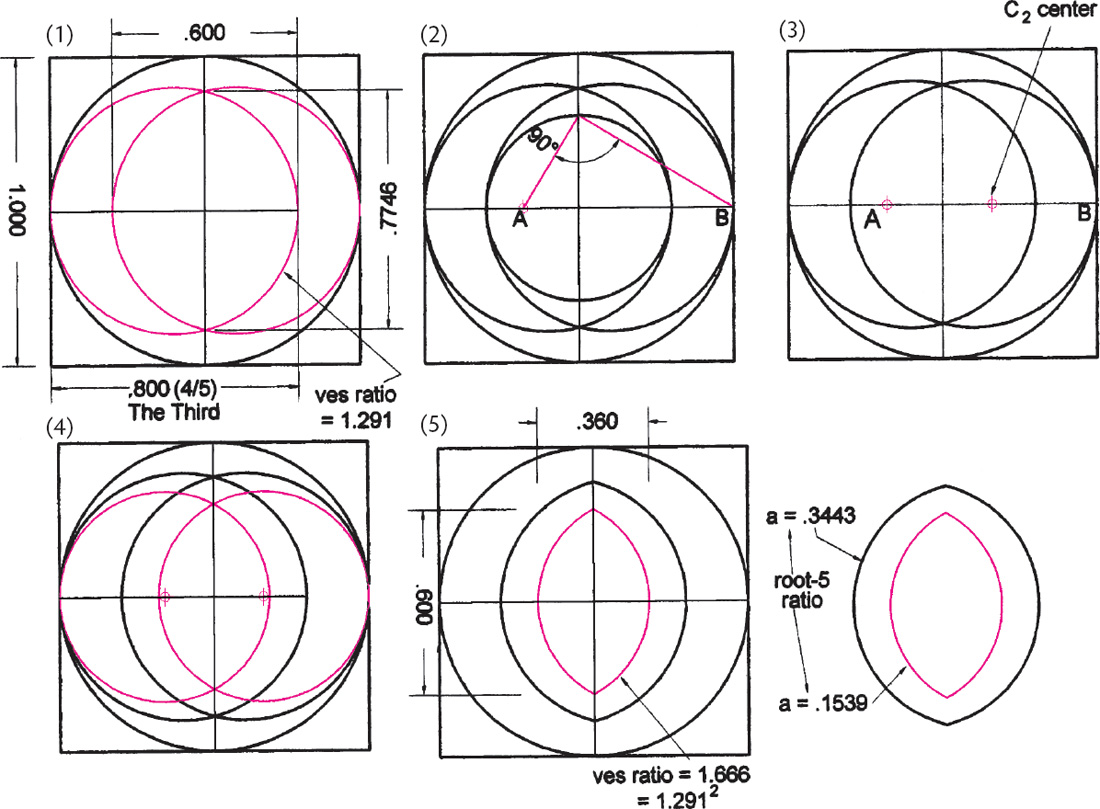

Drawing A2.11. A variation on the vesica-within-a-vesica ring concept as illustrated in the Athelstan psalter in drawing A2.10. In this example we generate a vesica within another vesica whose axis ratio is the square of the original. (1) A vesica construction is made. (2) A C4 circle is inscribed within the vesica. A line is drawn from the horizontal axis end B to the intersection of the C4 circle and the vertical axis. Another line is drawn perpendicular to this line to intersect the horizontal axis. (3) Line AB is bisected giving a C2 center. (4) This center is mirrored on the other side of the axis, and the C2 circles are drawn generating the new vesica. (5) The two vesicas have axis ratios in square relation. In this case the vesica areas happen to be in √5 relation.

Drawing A2.12. Continuing our vesica-within-a-vesica theme leads us to a structure in which both the inner and outer vesicas have the same ratio. The enclosing ring would then be the gnomon of the original vesica, a shape that Hero of Alexandria defined as “that form which when added to another form results in a new form similar to the original.”

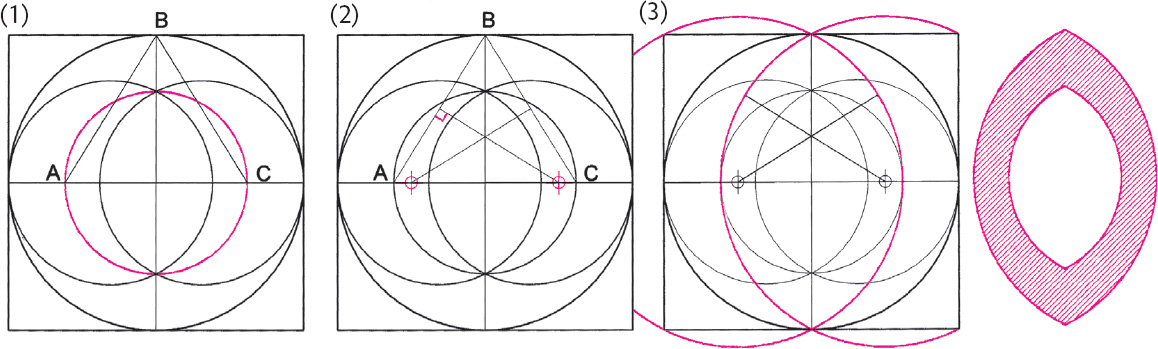

(1) A vesica construction is drawn. A C3 circle is drawn, and lines AB and CB are drawn connecting the C3 diameter ends with the end of the vertical axis. (2) Perpendicular bisectors of AB and CB intersect the horizontal diameter. (3) These intersection points are the centers of the new C2 circles that generate a new vesica with the same shape as the original vesica. The gnomon is the colored area between the concentric vesicas.

“Pointed arches as such were not new. Even in prehistoric ornament they appear automatically as the product of intersecting circles. The Treasury of Atreus has a dome whose section is a pointed arch. Greek mathematicians and Roman architects must have known the form. The important factor, however, was not knowledge of the form but the decision to use it in architecture. The Egyptians made use of it in sections of canals, but they, and after them the Romans and the Byzantines, would not have thought of using in in an exposed position. Islamic architects were the first to recognize its aesthetic and stylistic value.”

PAUL FRANKL, GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE.1

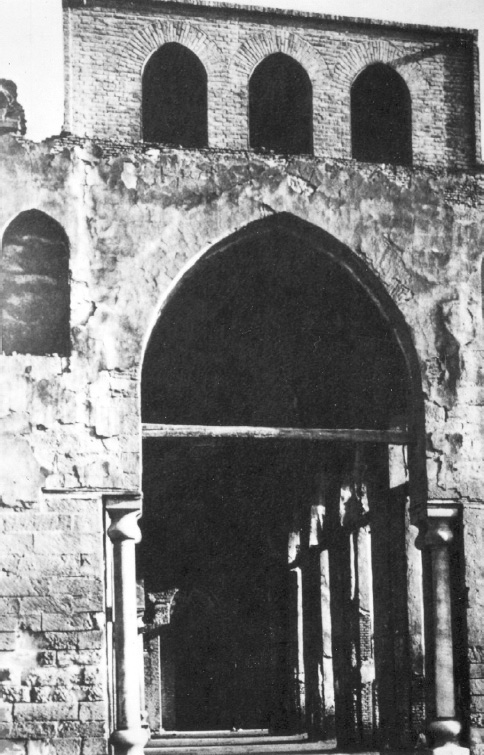

Figure A2.E. The Cairo Mosque of al-Hakim ca. 690 CE

Drawing A2.13. A design for an arch whose distance between centers is 1/5th the width of the arch. (1) The 6/7 point is located, and (2) the center point of the 6/7 length is found and mirrored, and the two C2 circles are constructed. The width of the resulting vesica = 5/7 (.7143) and the centers are at a distance of 1/7 from each other. We note that 6/7 (a septimal minor third) is an ancient tonal ratio cited by Ptolemy that has been used in Arabic scales.

“A new element was brought—the pointed arch, a geometrical revolution originating in Islamic sacred architecture. The origin of the pointed arch in Europe has been determined as being at the Italian Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassini, built 1066–71. . . . It was only a matter of time until all the geometric secrets of the Arab masons were incorporated into Western sacred architecture to form a new transcendent style—now known universally by its eighteenth-century derogatory name, Gothic.”

NIGEL PENNICK, SACRED GEOMETRY: SYMBOLISM AND PURPOSE IN RELIGIOUS STRUCTURES.2

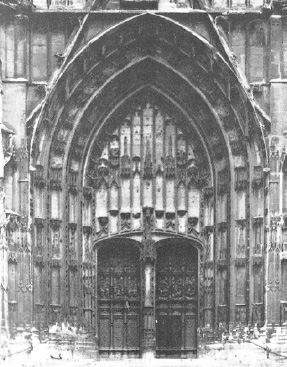

Figure A2.F. Portal of Amiens Cathedral, thirteenth century

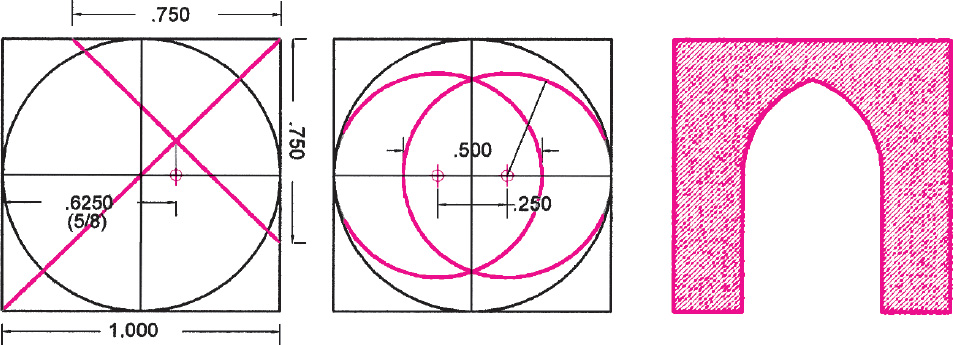

Drawing A2.14. The construction of a “drop arch” a type of Gothic arch in which the distance between arch centers is 1/2 the width of the arch. This arch is generated from the vesica construction at the minor-sixth tone resulting in a vesica with ratio = 2.

Drawing A2.15. Pottery constructions for nine tones generated from half- and quarter-square diagonals within vesica constructions. On the left, the pots are scaled so that their heights are equal.

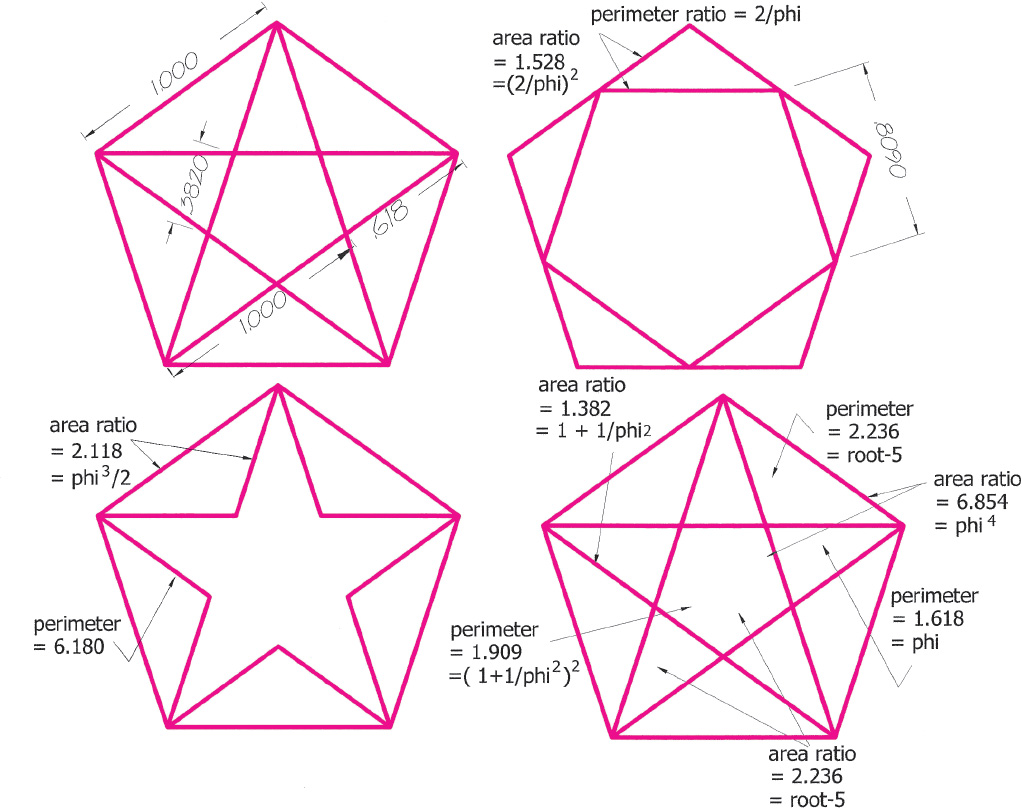

Drawing A2.16. An illustration of some of the many ϕ-family properties that are contained within the pentagon, the vessel of the golden ratio. On the upper left: the diagonals cross other diagonals at ϕ points. The base of the small triangles are .382 = 1/ϕ2. Upper right: the internal pentagon within the main pentagon has sides of .809 = ϕ/2. Perimeters and area ratios all have ϕ-family values. Lower left: the perimeter of the star = 6.180 = 10/ϕ. Lower right: the perimeters of all the elements are related to ϕ as are the area ratios.

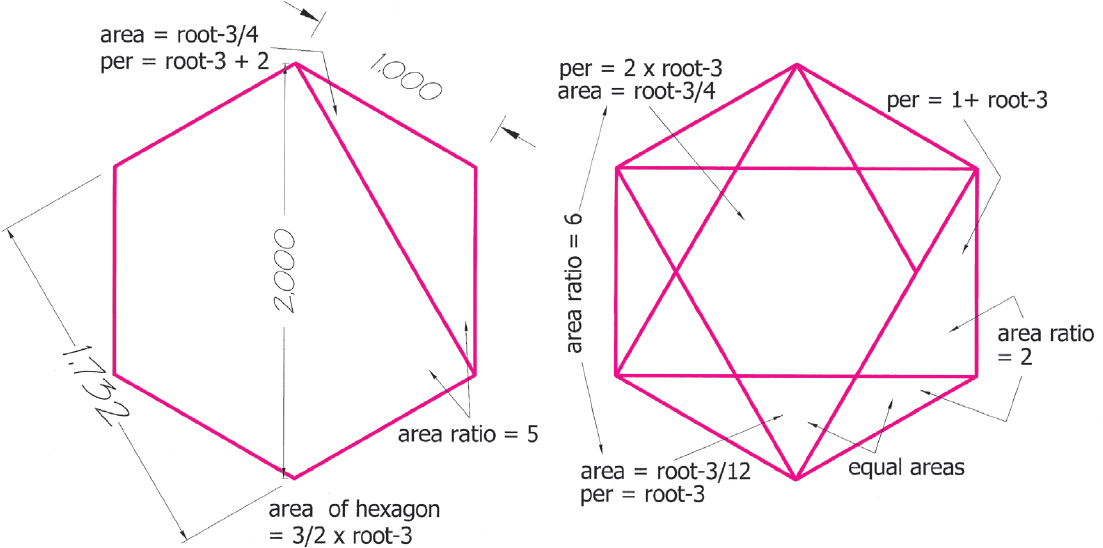

Drawing A2.17. An analysis of the hexagon in which some of its √3 (1.732) properties are shown. On the left we see how √3, or 1.732, is derived from the hexagon. The hexagon, while containing many √3 harmonies, also, as shown in both drawings, includes the ratios of 2, 5, and 6, which gives it a more universal quality than the pentagon whose inner dimensions seem to be completely dominated by ϕ. This universal quality becomes evident in the unfoldment of the vesica piscis (see chapter 11) from which all the polygons, including the pentagon, take form.

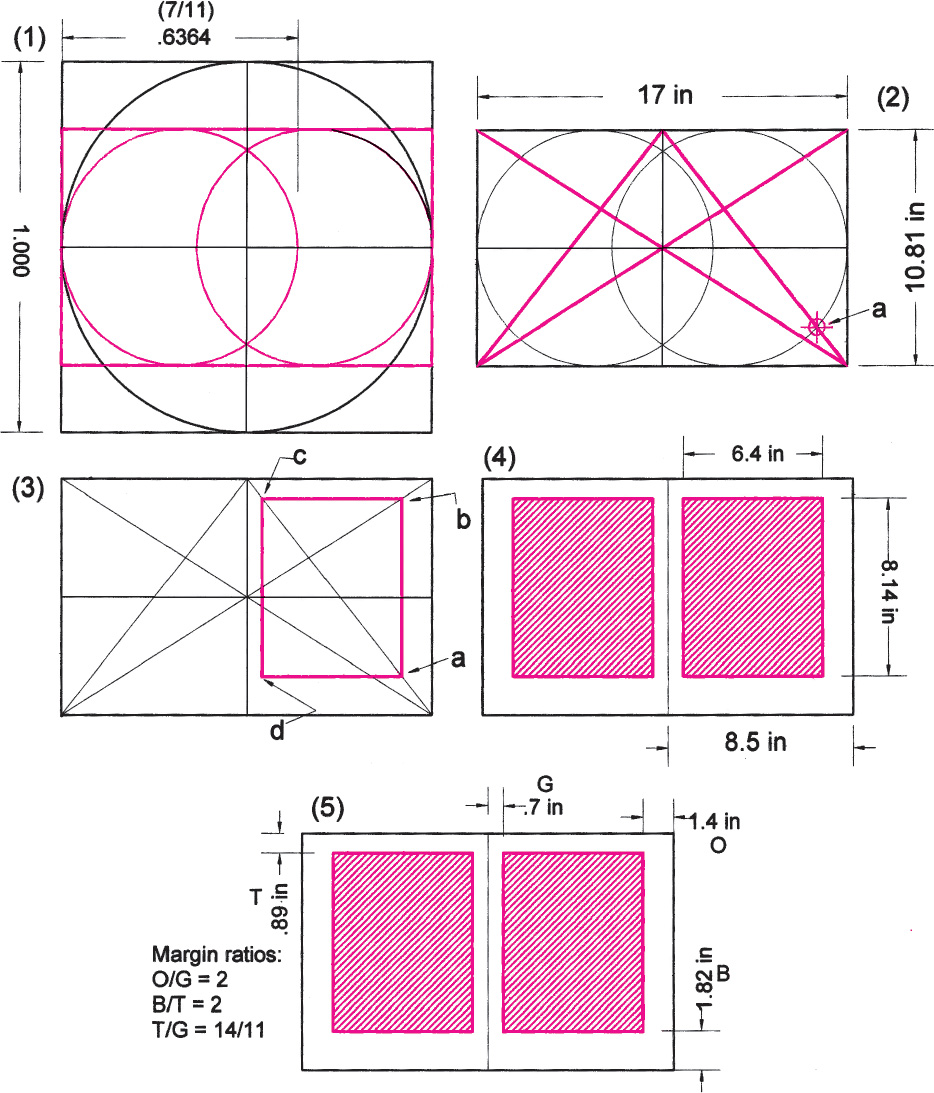

Drawing A2.18. A practical use to which rectangular space division using the vesica construction may be applied is the layout of the book page. Here is an example in which we use the 7/11 interval as the generating tone. The two-page sheet is the basic module of the book. In the context of the vesica construction the sheet becomes the rectangle that circumscribes the two C2 circles. In (2) half and full diagonals are drawn within the sheet rectangle, and a point a is located where the half-page diagonal intersects a C2 circle. (3) A vertical line is drawn from a to intersect a full diagonal at b. A horizontal is extended from b to a half-diagonal to give point c. A vertical from c intersects a horizontal from a at d, completing the text block that is then mirrored on the other page (4). In this example the ratio of the text block and the page are equal with ratios of 14/11. Margin ratios are shown in (5). While this construction uses the American standard paper sizes, the same construction could, of course, be made on metric-system paper.

Drawing A2.19. More book-page layouts based on musical tones and using the method shown in drawing A2.18.

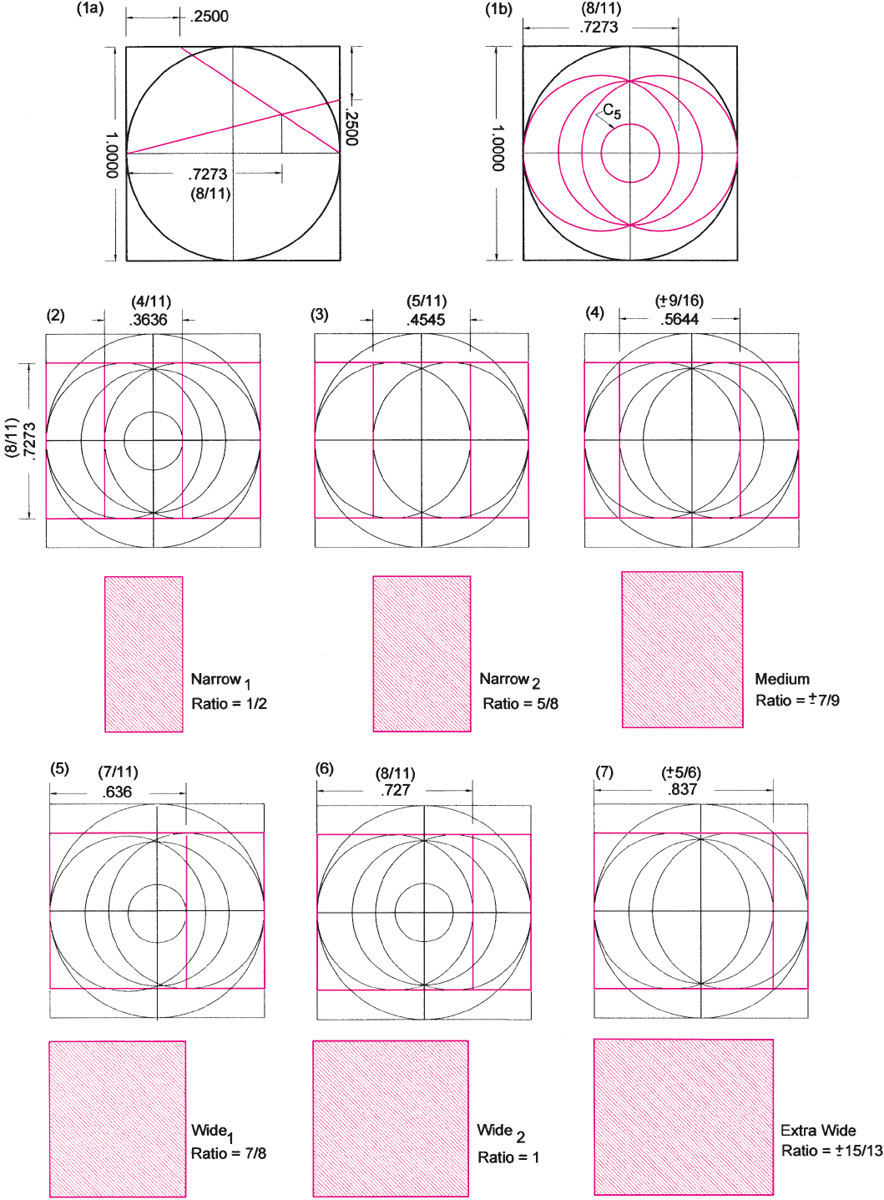

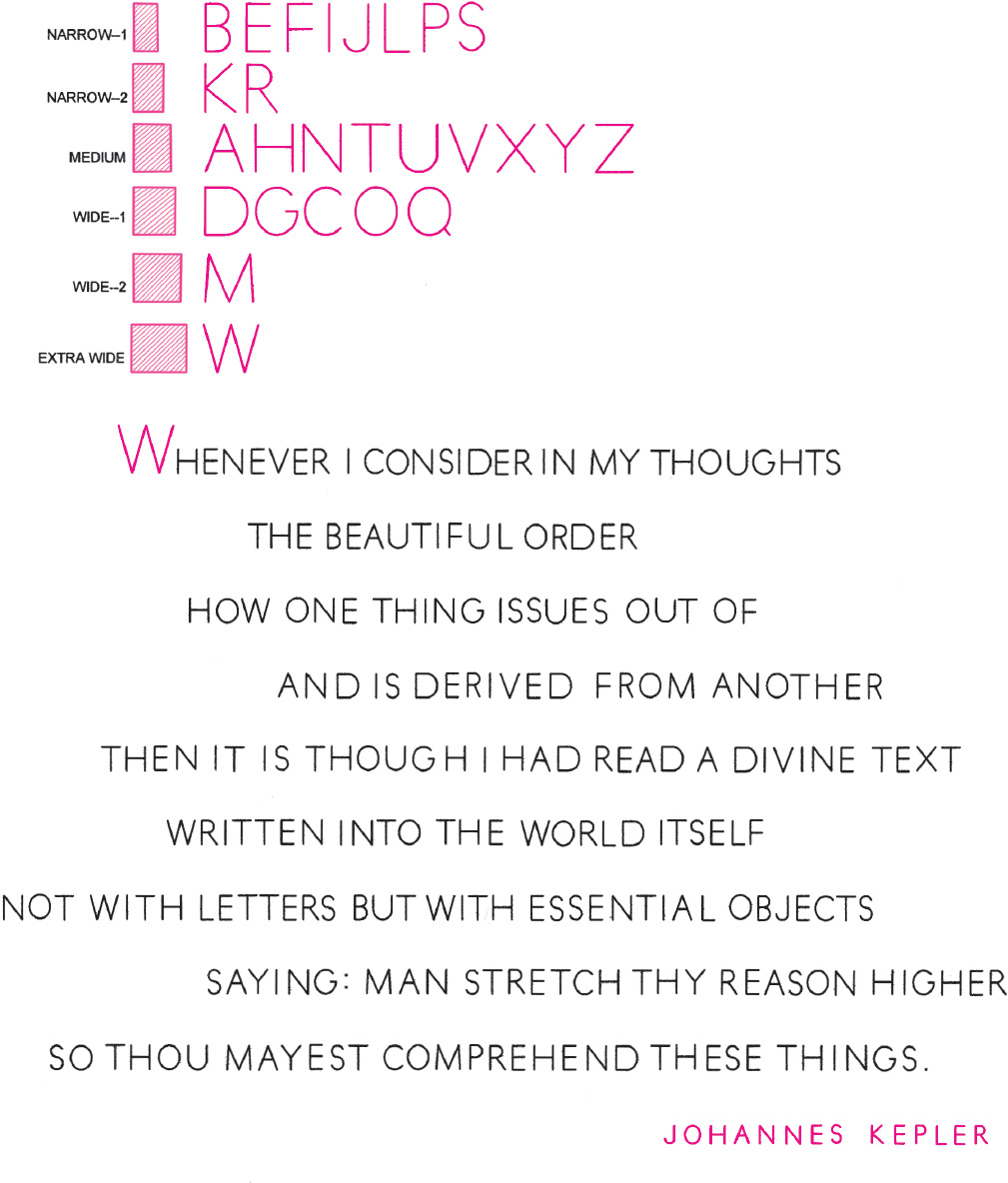

Drawing A2.20. The typeface designer or calligrapher may employ the vesica construction in its many forms for designing letter-width modules. After constructing (or measuring out) a ratio—in this case the 8/11 ratio—a vesica construction is generated (1a and b) and the various vesica circles are drawn. Through experiment, letter widths are found between various nodes formed by the elements of the construction.

Drawing A2.21. Letters and text generated from the module widths of the 8/11 tone demonstrated in drawing A2.20.

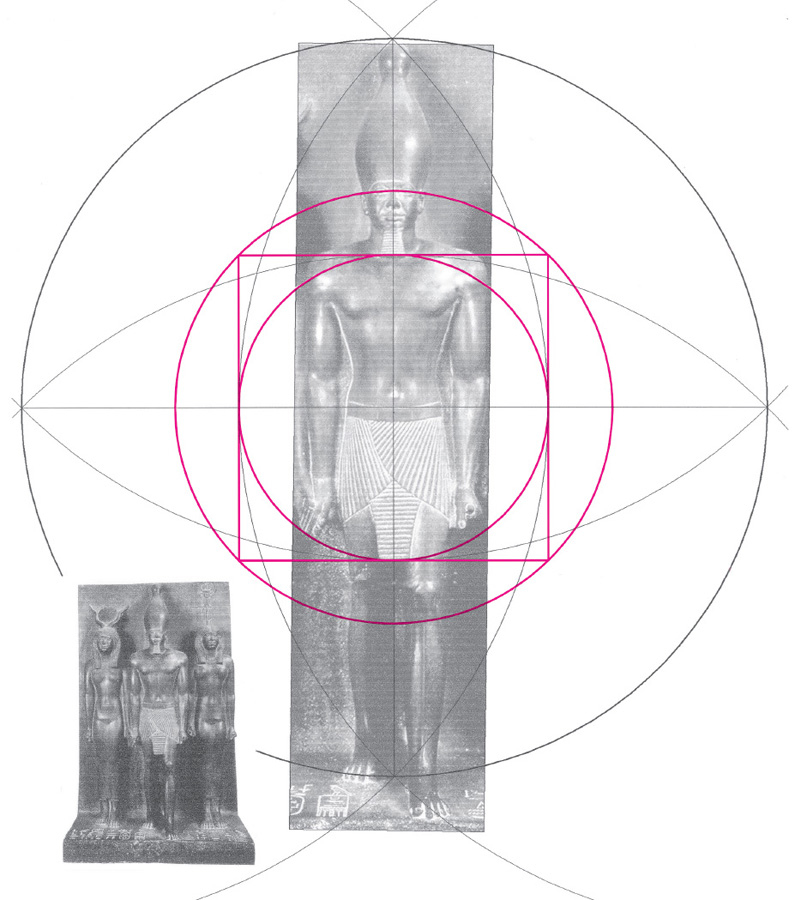

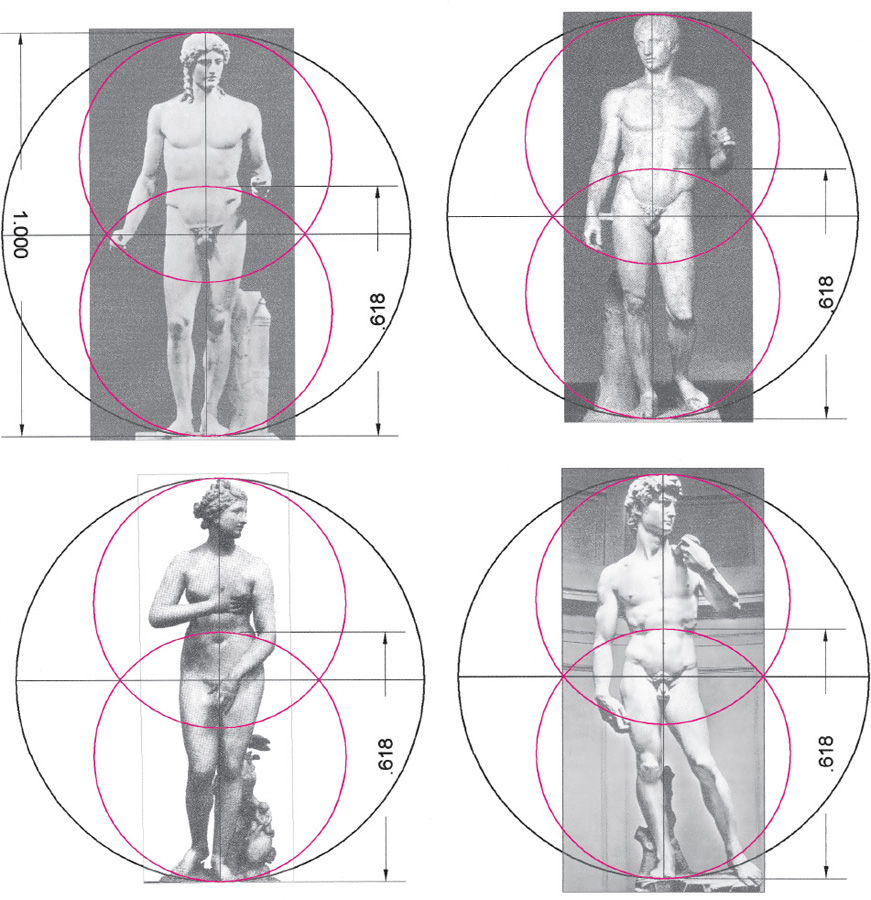

Drawing A2.22. The crossed-vesicas construction that we looked at in chapter 8 may have had a wide use in ancient art and architecture. Formed from arcs of the geometric tritone (drawing 8.6) a circle squaring is established generating a quadrature geometry that sculptors used to structure the proportions of the human body so that the vital centers were subtly emphasized. This harmonic approach when employed by consummate artists assisted them in their goal of manifesting ideal types of humanity. Our first example is an analysis of a sculpture of Pharaoh Menkaure of Fourth Dynasty Egypt using a crossed-vesica construction and quadrature that locates the second chakra, throat chakra, and brow chakra. The top of the crown may correspond to the seat of the soul, the “sky point” of the Egyptians. The intersection of fabric arcs on his kilt locates the root chakra. The whole is centered on the second chakra at the top of his kilt, the center of power in some traditions. The two geometric means, one from each end of the body-as-monochord, are placed at the ends of his ritual beard and the tongue of his kilt.

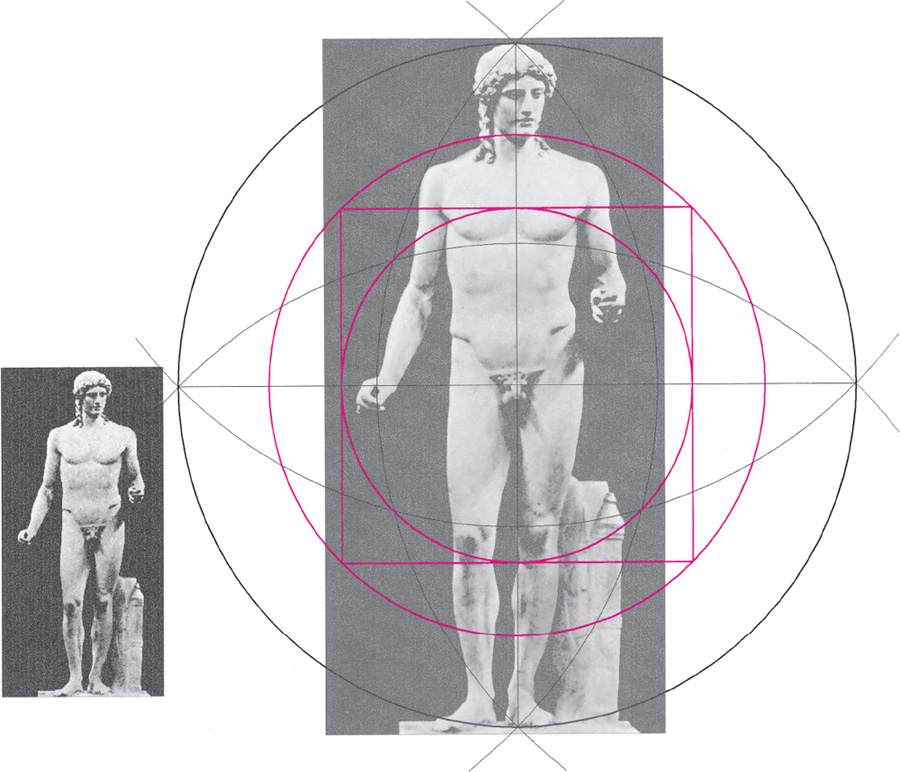

Drawing A2.23. The Cassel Apollo, a Roman marble copy of the Greek bronze original of ca. 470–460 BCE. In this and the other analyses in which we have overlaid the crossed-vesicas construction we notice the importance of the placement of the knees, which mirror the placement of the vital center of the heart-lungs at the fourth chakra. The human knees are essential to our upright stance and bipedality and have much to do with what it means to be human as evidenced by the sense of celebration that happens when a child begins walking. The hands are also freed up at this time. Mircea Eliade writes: “It is sufficient to recall that the vertical posture already marks a transcending of the condition typical of the primates. Uprightness cannot be maintained except in a state of wakefulness. It is because of man’s vertical posture that space is organized in a structure inaccessible to the prehominians: in four horizontal directions radiating from an ‘up’‘down’ central axis. In other words, space can be organized around the human body as extending forward, backward, to right, to left, upward, and downward. It is from this original and originating experience—feeling oneself ‘thrown’ into the middle of an apparently limitless, unknown, and threatening extension—that the different methods of orientatio are developed; for it is impossible to survive for any length of time in the vertigo brought on by disorientation. The experience of space oriented around a ‘center’ explains the importance of the paradigmatic divisions and distributions of territories, agglomerations, and habitations and their cosmological symbolism.” 3

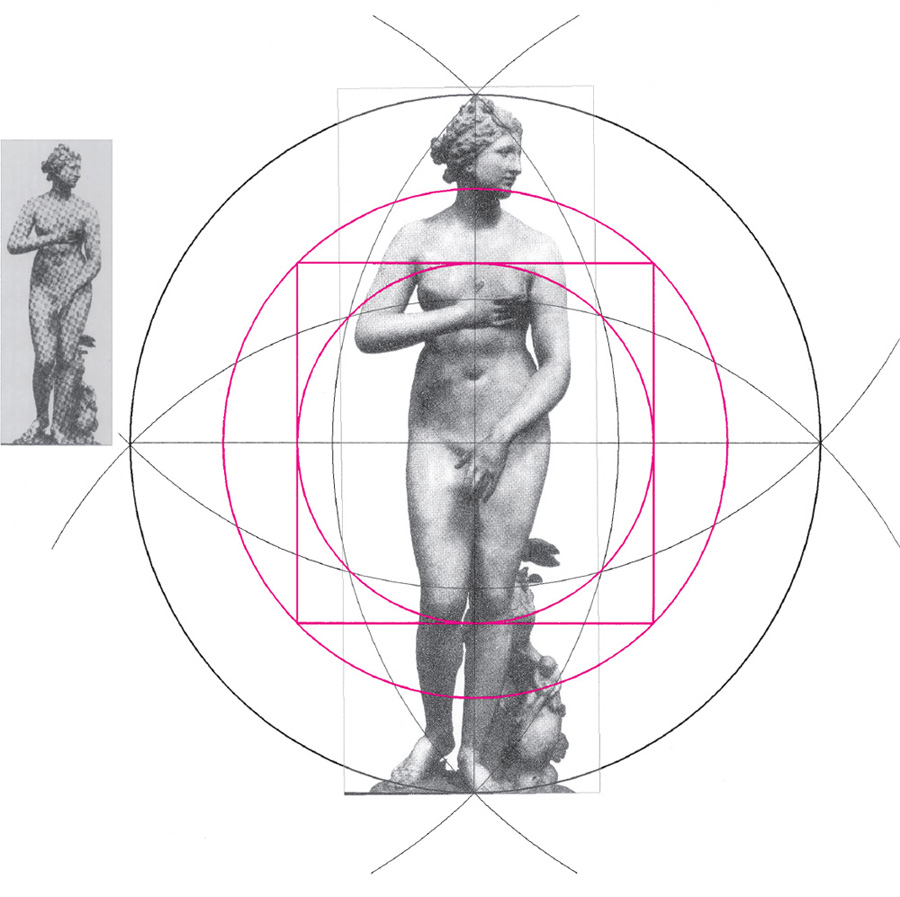

Drawing A2.24. The Medici Venus by a follower of Praxiteles, marble, ca. 300 BCE. The same crossed-vesicas geometry as we have previously seen is applied to the female body. Here, again, the essential bodily elements are clearly set out—the head with its regulating functions: the root chakra at the center; and, at the geometric means, the heart-lung node (centers of breath and feeling) and the knees, whose function produces the unique upright stance of the human.

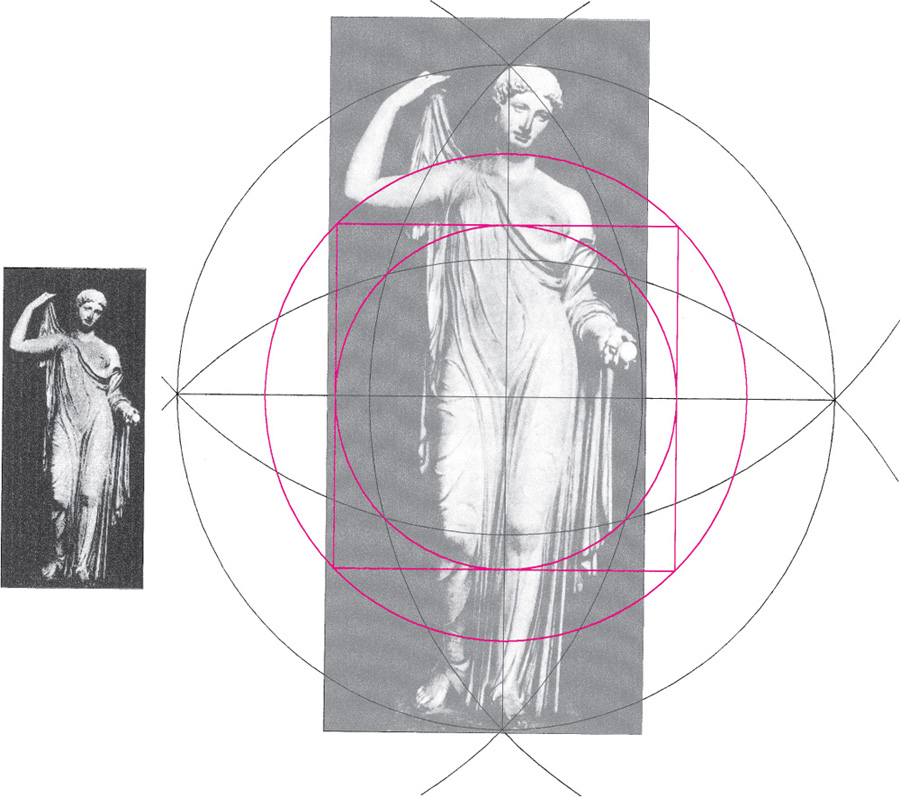

Drawing A2.25. Aphrodite from Frejus. Roman marble copy after Greek original of ca. 430–400 BCE. Is it coincidence or angular illusion that the proposed guidelines are tangent to the upraised hand and the ball in the other hand? In any event such cues would make the accurate copying of sculpture a bit easier.

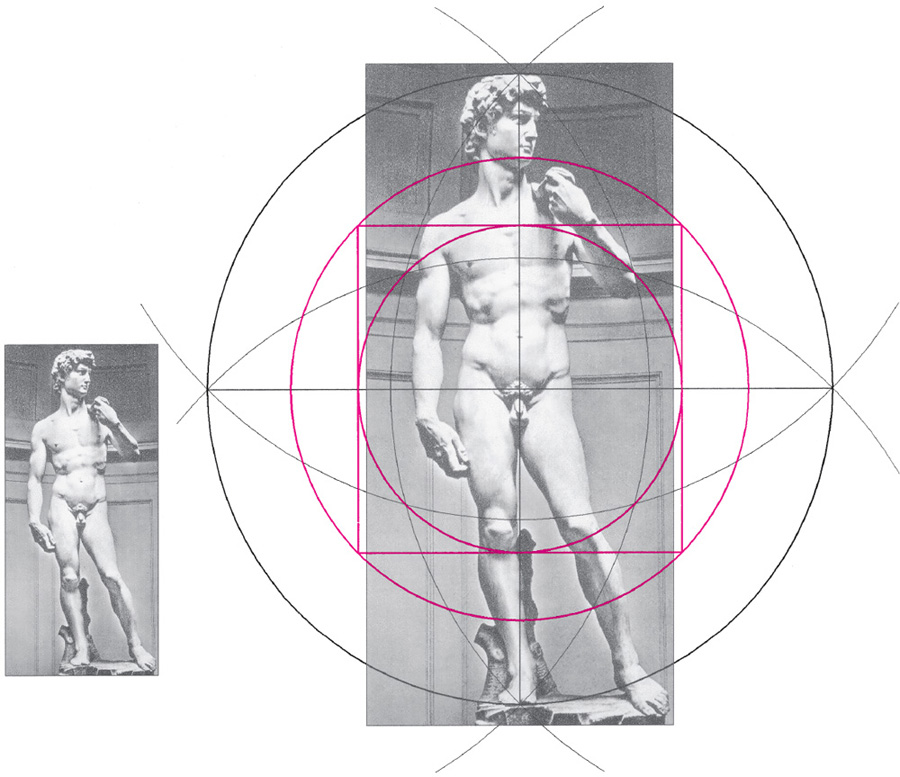

Drawing A2.26. Michaelangelo’s David, sculpted about 2,000 years after the classical Greek sculptures and of quite different composition yet with a similar arrangement of groin, chest, knees, and head as ordained by the crossed-vesicas construction. This is an example of the rediscovery of classical proportional standards by Renaissance artists.

Drawing A2.27. Mannikkavachakar, a seventeenth-century Indian sculpture in which we see a variation of the classical crossed-vesicas construction. While in most of the previous analyses the center was at the root chakra, in this case the center is at the second chakra slightly below the navel (as in the Pharaoh Menkaure sculpture). The heart-lung area, the fourth chakra, is at the geometric mean position. The next circle locates the throat chakra, which is at the same distance from the center as the knees. The next circle intersects the brow chakra.

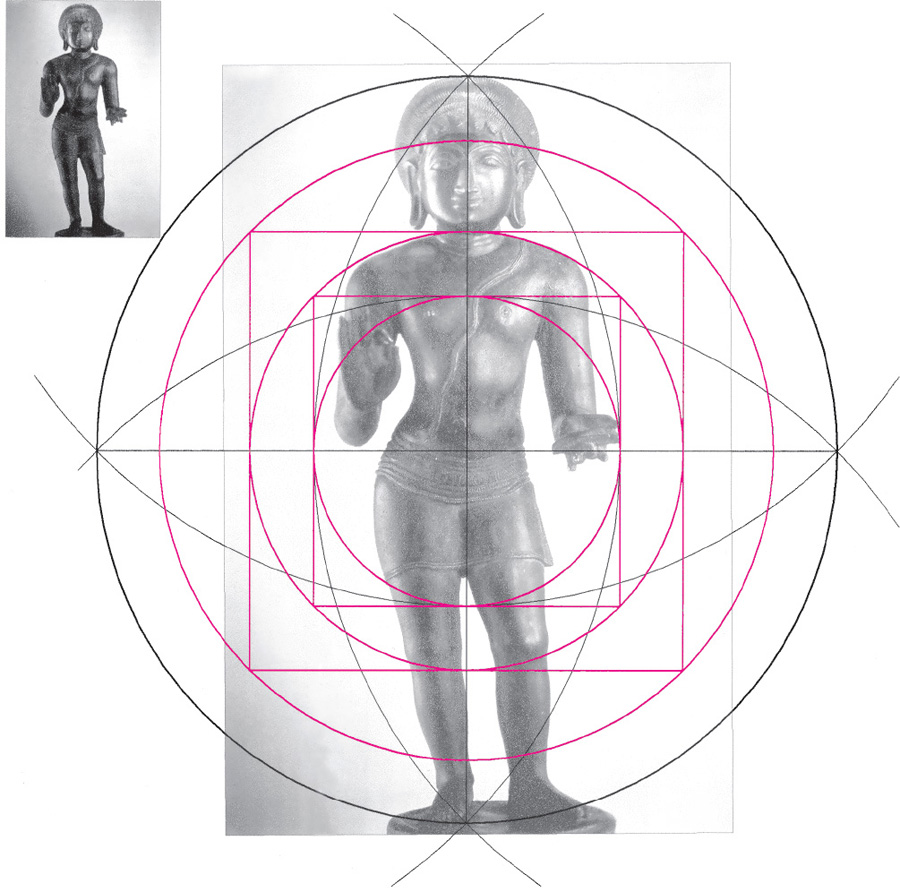

Drawing A2.28. Four of the previous sculptural analyses with their golden section points in the area of the solar plexus, the third chakra.

Drawing A2.29. An example of doubling quadrature generated from crossed vesicas used to generate a temple plan. This is the ground plan of the ancient Osirion temple at Abydos, Egypt.

(1) A containing circle is drawn to the vertical ends of the structure.

(2, 3, 4, 5) The crossed vesicas are drawn.

(6) A square is drawn to the intersecting points of the crossed vesicas.

(7) A circle, also drawn to these points, circumscribes the square.

(8) A square circumscribes the circle of (7).

(9) A circle circumscribes the square of (8).

(10) A final square circumscribes the circle of (9).

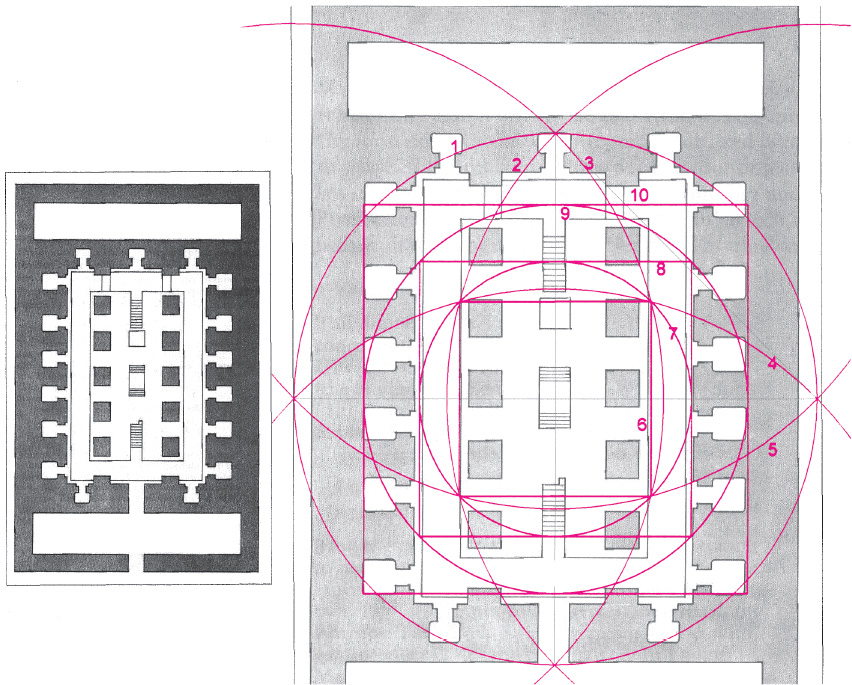

Drawing A2.30. A setting-out of some elements of the Vaikunthaperumal Hindu temple at Kanchipuram, India, eighth century CE, using a crossed vesica and quadrature construction. (1) The building is composed of nested squares. Beginning with a central circle the crossed geometric tritone vesicas are drawn. Their components immediately give all the essential layout directions. (2) The outer crossings of the vesica-generating circles provide points to draw the containing square. The inner square and middle square are also drawn to the points provided by the original geometry. (3) Another square between the inner and middle squares is drawn with the help of diagonals that cross the containing square.

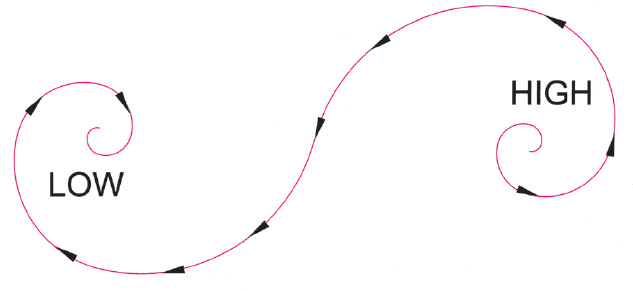

Drawing A2.31. The shape of the wind when, as it streams out of the high-pressure areas, is sucked into the low-pressure areas. The wind direction in the drawing occurs in the Southern Hemisphere, flowing counterclockwise out of the high and clockwise into the low.

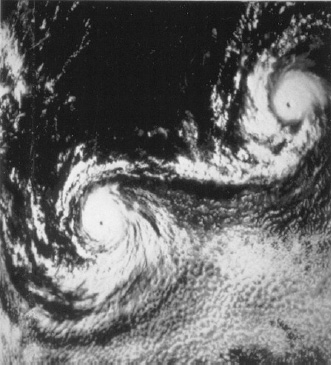

Figure A2.G. A similar pattern to the shape of the wind (drawing A2.31) is demonstrated when two hurricanes approach each other exhibiting the “Fujiwhara effect.” Shown here are Iona at lower left and Kirsten off the Pacific coast of Mexico in the month of August 1974.

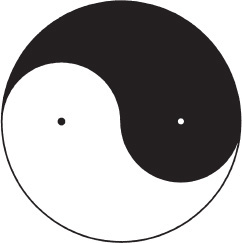

Figure A2.H. The taiji symbol and liquids mixing in a cup have a similar interlocking spiral pattern as that of the winds.

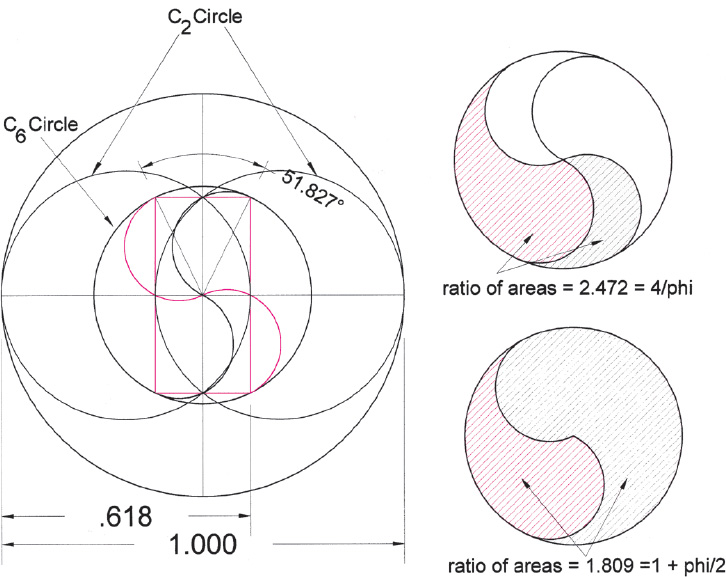

Drawing A2.32. The taiji symbol

Drawing A2.33. The taiji, when revolved, becomes a circle-dividing tool. We need only have an angle of rotation to construct a second pair of vanes. A vesica construction can be used to set this out. Given an angle, in this case the Great Pyramid base-to-apothem angle of about 51.827°, we first divide the angle in two and then take the 1/tan of the result, which gives our vesica ratio with which we may make a construction. Half of this angle is 25.913°, and the reciprocal of its tangent equals 2.058 (ϕ × √ϕ). After drawing the vesica construction, with its C2 circle = .618 (1/phi), the next step is to circumscribe the vesica with a rectangle and then to circumscribe the rectangle with a circle (C6). This is the taiji circle. The revolved taiji vanes are constructed to intersect the rectangle corners and divide the C6 circle as shown. On the right are the resulting ϕ-based area ratios.

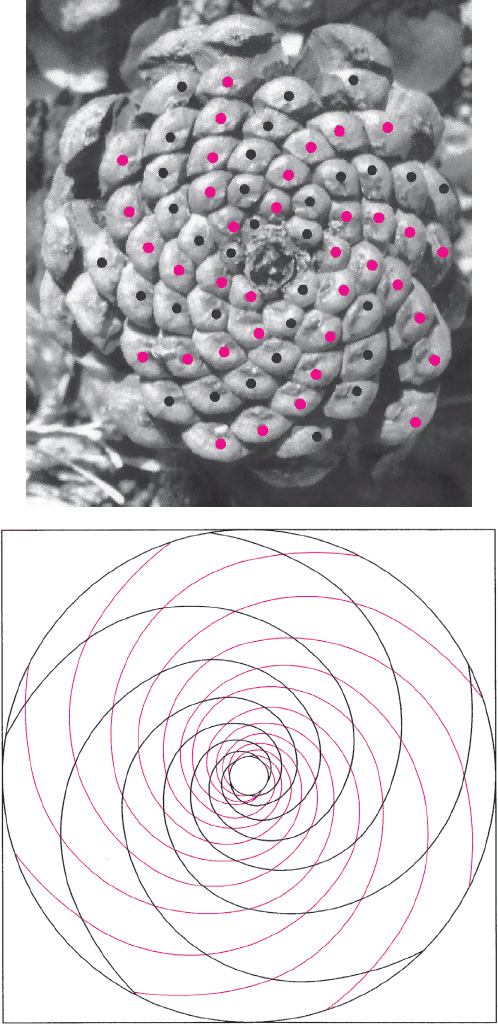

Drawing A2.34. Fibonacci numbers in nature. On the top is a pinecone with an 8/13 system of opposing spirals. Thirteen rows spiral clockwise, each row having either all red or all black dots. Eight rows spiral counterclockwise, each having alternating red and black dots. On the bottom is another similar pattern—a 5/8 array of opposing spirals. Both of these are Fibonacci patterns that can be found throughout nature in the seedheads of flowers such as the sunflower.

The Fibonacci series is a summation series in which each number of the series is the sum of the two previous numbers:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1,597, and so on.

For example, on a large seedhead there may be 89 spirals going one way and 55 the other way, or 55 one way and 34 the other way. The quotients of any two adjacent ratios gradually approach yet never quite reach the irrational ratio of ϕ = 1.6180339. . . . Thus:

1/0 = ∞; 1/1 = 1; 2/1 = 2; 3/2 = 1.5;

5/3 = 1.666; 8/5 = 1.6; 13/8 = 1.625;

21/13 = 1.61538; 34/21 = 1.61904;

55/34 = 1.61764; 89/55 = 1.61818;

144/89 = 1.61797; 233/144 = 1.6180555;

377/233 = 1.6180257;610/377 = 1.618037135;

987/610 = 1.6180345; 1,597/987 = 1.6180345;

and 1.6180345/1.6180339 . . . (ϕ) = 1.000000371, the degree of accuracy in relation to ϕ at this stage of the Fibonacci series.

We recognize the ratios of the Fibonacci series to be musical intervals. In terms of string length: 1/1, the unison; 1/2, the octave; 2/3, the fifth; 3/5, the sixth; 5/8, the minor sixth; followed by more unusual intervals. The first interval, 1/0 whose quotient equals ∞, might suggest that the series has its origin in the infinite. The next interval, 1/1, the unison, is the relation of two identical tones. Levy and Levarie say of this interval,

There is only one perfect consonance between two tones: the unison. . . . All other intervals . . . are more or less dissonant. . . . The underlying assumption is some musical unity, a oneness of sound, in which the partaking tones lose their identity. Acoustics offers us two prominent manifestations of such a unity: the oneness of the string which vibrates simultaneously as a whole and in parts, and the oneness of the harmonic series which forms one tone. . . .4

An example of unison in nature is the apparent equality of sizes between Sun and Moon, which is most obvious during a solar eclipse. In geometry we have seen a striving toward unison in the circle-squaring practices discussed earlier in the book.

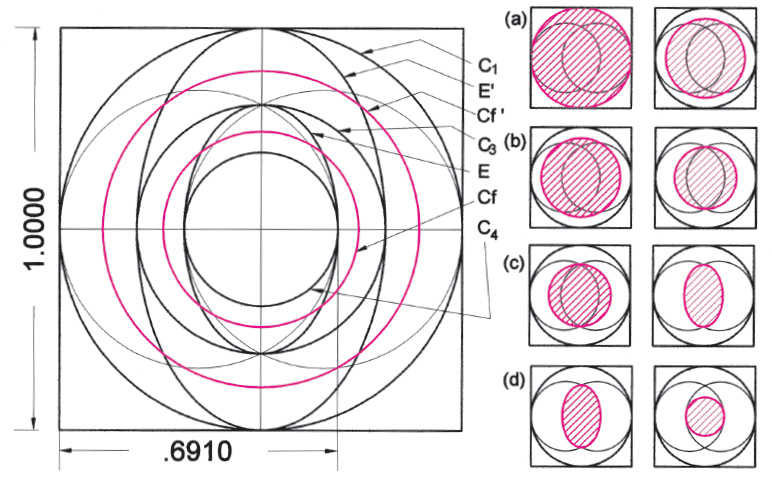

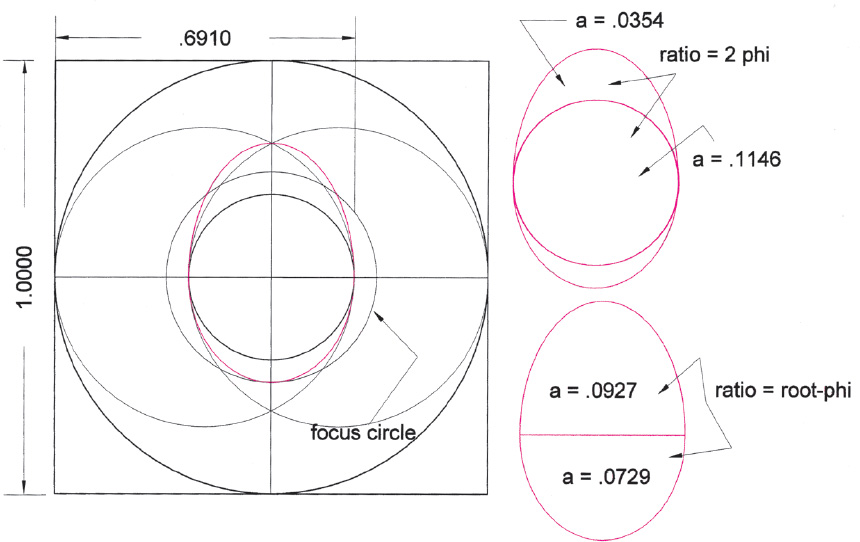

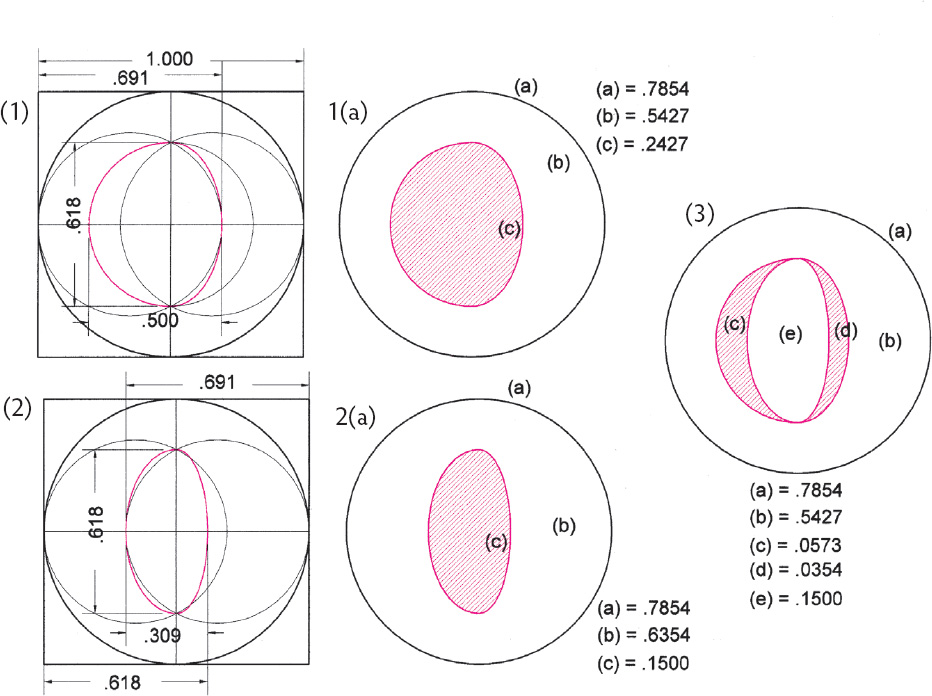

Drawing A2.35. The vesica and the ellipse. The ellipse can be seen as the “fulfillment” of the vesica, rounding off its sharp poles and transforming it from a geometric symbol into a more natural object with innumerable manifestations from the shape of certain galaxies to the orbits of planets to the forms of microbes. Geometrically the area of the vesica itself seems discordant within the vesica construction, that is, there is no simple proportion that joins it to its inner (C4) and circumscribing (C3) circles. However, when we transform it into an ellipse a geometric proportion emerges: C3/ellipse = ellipse/C4. The above drawing of our familiar ϕ-tritone vesica construction includes two ellipses forming an ellipse ring, that is, an ellipse around the vesica and an ellipse connecting the C1 containing circle and the C3 circle. We have also added two other circles to the construction, the ellipse focus circles, Cf, which join the foci of each ellipse. The following are the areas and area ratios of the elements of the construction.

| C4 = .1146 | (a) C1/Cf ’ = ϕ (1.618) | |||

| Cf = .1854 (focus circle) | (b) Cf ’/C3 = ϕ | |||

| E = .1854 | (c) C3/E = ϕ | |||

| C3 = .3 | (d) E/C4 = ϕ | |||

| Cf’ = .4854 (focus circle) | ||||

| E’ = .4854 | ||||

| C1 = .7854 |

Also, E’ is the arithmetic mean between E and C1; E is the geometric mean between C3 and C4. The progression of numbers .1146, .1854, .3, .4854, .7854 is an additive progression in which each number is equal to the sum of the two previous numbers. The series can also be transposed into the series 1, ϕ, ϕ2, ϕ3, ϕ4. The eccentricity of the ellipses is .7861 = 1/√ϕ.

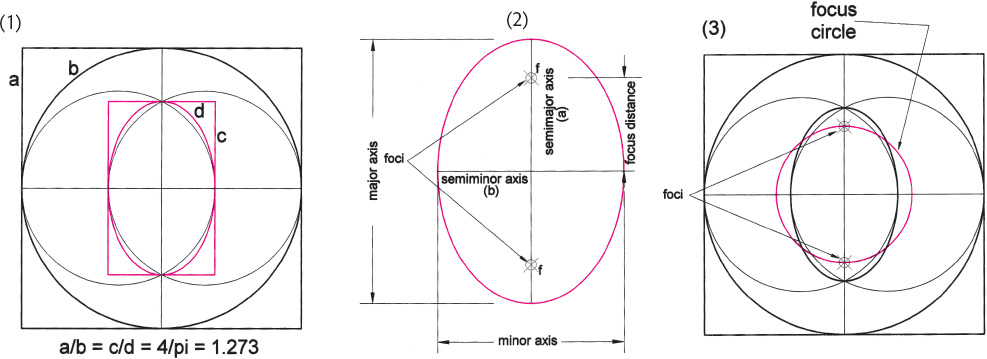

Drawing A2.36. Three drawings of the ellipse that help to describe this shape. In (1) we demonstrate how the square is to the circle as the rectangle is to the ellipse—they form a proportion that equals 4/π, or 1.273. (2) The principal properties of the ellipse are shown. Given the lengths of the axes, the foci can be calculated with the formula: f2 = a2 − b2 where a is the semimajor axis and b is the semiminor axis and f is the distance from the center to the focus. The equation for the area of the ellipse is area = abπ. The eccentricity of the ellipse ranges from 0 to 1 and is given by the equation e = f/a. (3) The focus circle is constructed.

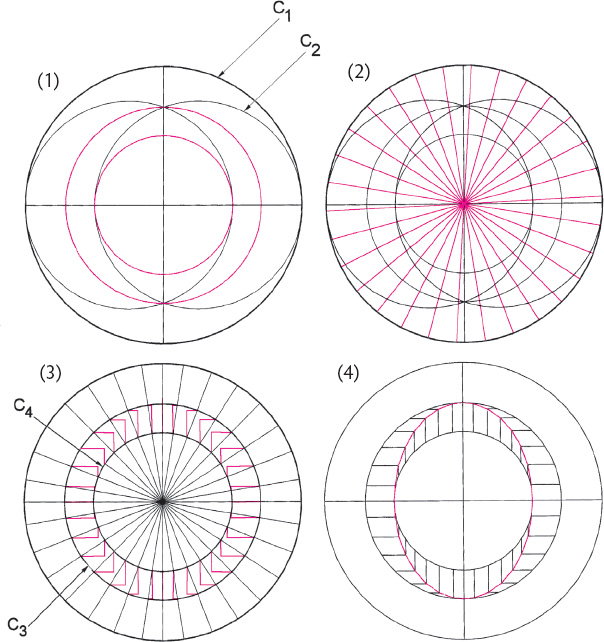

Drawing A2.37. Drawing an Earth ellipse. A simple way to draw a large-scale approximate ellipse on the ground is by beginning with a vesica construction (1). In (2) radii are drawn from the center to the C1 circumference. (3) Verticals are drawn from the radii/inner circle (C4) intersections and horizontals are drawn from radii/outer circle (C3) intersections. (4) The intersections of verticals and horizontals form a path on which an ellipse may be drawn.

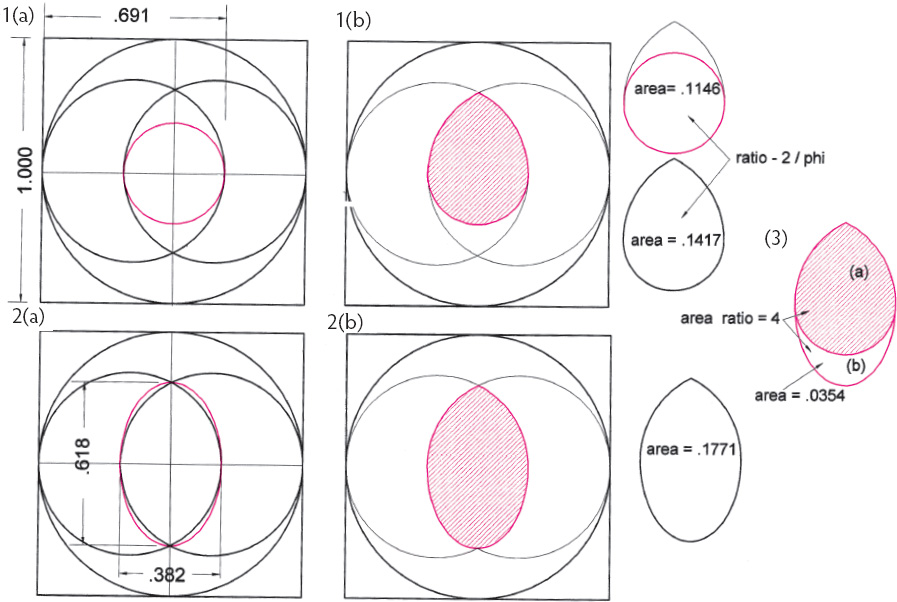

Drawing A2.38. Among the innumerable forms that seeds take, a common shape can be drawn from a vesica combined with a circle or an ellipse. The vesica construction enables us to create seed forms from the numbers of musical intervals or, in the present case, from ϕ-based numbers. In (1) the seed is a composite of the vesica and the C4 circle. Its area is about 1/7th of the enclosing square. Its height-to-width ratio equals ϕ2/2. The areas of seed and C4 circle are in 1.236 = 2/ϕ ratio. (2) A composite of a vesica and a vesica ellipse. Its height-towidth ratio equals ϕ. (3) The two seeds are conjoined with area ratio a/b = 4.0.

Drawing A2.39. The shape of eggs. Harmonious egg shapes can also be drawn from the vesica/ ellipse construction. Here the top part of the egg is a half ellipse derived from the ϕ-tritone vesica construction. The bottom part is a half ellipse with a long axis that extends to the vesica ellipse focus circle. The axis ratio of the egg = 1/.691 = 1/(1 + 1/√5).

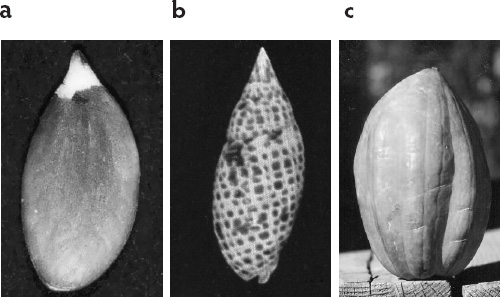

Figures A2.I. Many (or most) shapes in nature s are more or less asymmetrical, a quality that gives them a one-of-a-kind beauty: (a) pumpkin seed, (b) Mitra cardinal is shell, and (c) acorn squash. This fact of nature inspires us to create offset shapes with harmonious proportions.

Drawing A2.40. Asymmetrical harmonies. Two asymmetrical figures that separately and conjoined produce a variety of ϕ family ratios. The area values are shown next to the figures. (1) Half of the vesica ellipse is combined with the C3 semicircle producing an offset shape with area of .2427 = 1/(2ϕ × √ϕ).

| Area ratios: | a/b = 1.4471 = 1/√5 | ||

| a/c = 3.236 = 2ϕ | |||

| b/c = 2.236 = √5 |

(2) A composite of the ellipse at the .691 tonal position and the ellipse at the .618 tonal position. The area of the offset shape (c) = .15 = 1/2ϕ2 × √ϕ.

| Area ratios: | a/b = 1.236 = 2/ϕ | ||

| a/c = 5.236 = 2ϕ2 | |||

| b/c = 4.236 = ϕ3 |

(3) Combining the figures in (1) and (2) generates a figure with the following ratios.

| a/b = 1.4472 | b/d = 15.330 = ϕ4 × √5 | ||

| a/c = 13.706 = 2ϕ4 | b/e = 3.618 = ϕ × √5 | ||

| a/d = 22.186 = 2ϕ5 | c/d = 1.618 = ϕ | ||

| a/e = 5.236 = 2ϕ2 | e/c = 2.618 = ϕ2 |

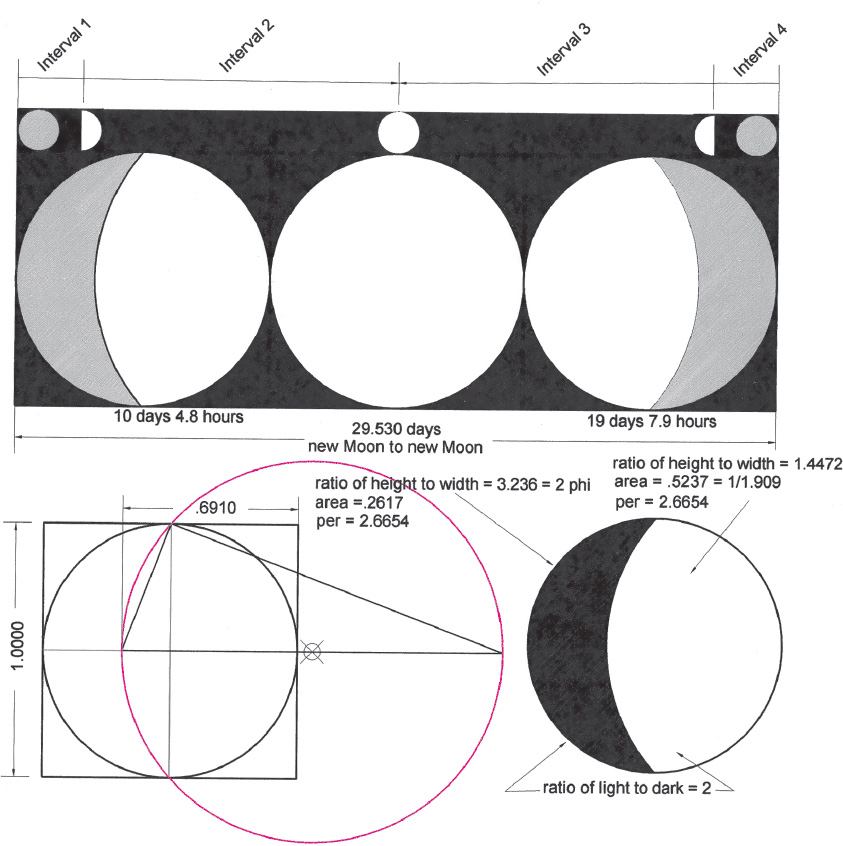

Drawing A2.41. Moon octaves. The Moon in its phases has a musical quality manifested in the steady advance of the dark/light line, the terminator, across its diameter imagined as a musical string. In this diagram we see the diatonic tonal positions of the Moon as its string/diameter is stopped at specific points and plucked. (Of course, all possible tones are silently sounded during the lunation, tones that correspond to each second of the monthly cycle.)

Four octaves are sounded during the course of a month. With this phenomenon we have a manifestation of both time and space measures expressed as a unity. For example, at the fifth (G) position between new and first quarter, the terminator touches the Moon diameter of 2,160 miles at the 1,440 mile point (2/3 × 2,160 = 1,440). The number 1,440 is a key number in time measurement being the number of minutes in a day. It is also four times the number of degrees in a circle; and 144 is 1/6 of 864, the Sun number (i.e., Sun diameter = 864,000 miles).

The 2,160-mile standard chosen for the Moon has, as previously discussed, a temporal significance since 2,160 is the number of years in a Great Month, or Age, of the precessional cycle, the Great Year of 25,920 years. Thus our intervals seem to be stepping off cosmic time during the lunation cycle.

Besides these indications of the time-space quality of the lunation we note the well-known physical and emotional influences that the Moon has on life-forms, including its effects on the human psyche. The creative process may also be enhanced when the creator becomes aware of the lunar cycles. From the author’s experience the time from new to first quarter is a time of seeding of ideas and of inspiration; from first quarter to full, a time of action and creation; from full to last quarter, a time of finishing up; from last quarter to new, a time of rest, contemplation, and integration.

Drawing A2.42. The Moon at the ϕ tritone. Four tonal regions make up the lunation as described in drawing A2.41. Here we have concentrated on the shape of the Moon at the ϕ-tritone position (between F and G) in regions 2 and 3 during the waxing and waning gibbous periods of the lunation in which the light and dark lunar areas are in a 2:1 ratio. This configuration results in several ϕ-family numbers as shown.

We have discussed the harmonious geometric properties of this ϕ-tritone tonal position throughout the book. Here we see it applied to the relation of the light to dark areas of the Moon during the lunation. The ϕ tritone is a transition stage between, on the one hand, the complete darkness of the new moon and the brilliance of the full moon; and, on the other hand, between the full moon and the return to the darkness of the new. In both stages the light predominates over the darkness in a ratio of 2 to 1.

For the creator working within lunar time the first of these two stages occurs during a time of concentrated work that is illuminated by the growing light. The second stage occurs during the time of perfecting the work before the growing dark prevails and the creator returns to rest within the profound peace of stillness, of darkness.

Figure A2.J.

The unseen dark plays on his flute

and the rhythm of light

eddies into stars and suns into

thoughts and dreams.

RABINDRANATH TAGORE5