6

THE SPIRALING OCTAVE

ONE PURPOSE OF THIS BOOK IS TO ENCOURAGE readers to become familiar with the ancient tools of tone, number, and geometry in order to use them to create new forms—forms that will reflect the harmonies inherent in the numerical structures of the world. We have previously seen a few examples of how such tools might have been used by the ancient temple builders. And, in our exercises with planetary and lunar dimensions we have discovered possible harmonic processes behind their formation.

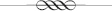

In this chapter we will use our tools to create harmonious forms using two essential figures of the harmonic realm—namely, the octave and the spiral. The numbers that emerge from these experiments will be expressed geometrically in order that we may visually experience them. Let us begin by again looking at our Earth-Sun construction, yet this time in the context of an octave-halving progression of the Earth diameter. We consider the Sun of 864,000 miles diameter equal to 1 and the Earth of 7,926 miles diameter equal to 1/109. We need to bring this fraction into the main octave, which we can do by doubling it 6 times:

2/109, 4/109, 8/109, 16/109, 32/109, 64/109.

The sixth double, 64/109 (.5872), can be located on the string/diameter of the Sun circle using crossed diagonals as shown in drawing 6.1 (below). A circle is drawn that intersects the generated point on the horizontal diameter and extends to the circumference of the enclosing Sun circle. Locating the center of the initial 64/109 circle gives us the first octave point at 32/109, and we draw a circle through it as we did with the main octave point. We continue until we reach the sixth octave, whose circle is the size of the Earth circle in relation to the containing Sun circle.

The Number 108 is important in spiritual and cosmic contexts. The Zen priest wears a juzu, a bracelet with 108 beads. The Hindu has a japa mala rosary with 108 beads. The Tibetan Buddhists also have a 108-bead rosary. Some say there are 108 gopis, the female disciples of Lord Krishna. Both Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine recognize 108 pressure points on the body. Yang-style tai ch’ i has 108 moves. There are 108 dance forms in the Indian tradition. The ratio 3/11, the Moon/ Earth diameter ratio, multiplied by 108 is equal to 29.455, which is within .997 of 29.53, the days in a lunation. And 108 divided by 4 equals 27, within .988 of the lunar sidereal period of 27.32 days. The number 108 times the 2,160-mile diameter of the Moon equals 233,280 miles, which is about the average distance from Earth to Moon. (Oddly enough, about the same distance, i.e., 234,054, results from multiplying Earth’s diameter of 7,926 by the lunation cycle of 29.53 days.) And 108 times Earth’s diameter of 7,926 miles equals 856,008 miles (the Sun diameter within 99 percent). Substituting our “ ideal Earth” of 8,000 miles, as described in the text, makes the Sun diameter exact at 864,000 miles; and 108 times this Sun diameter equals 93,312,000 miles, which is the average of the Earth-Sun distance.

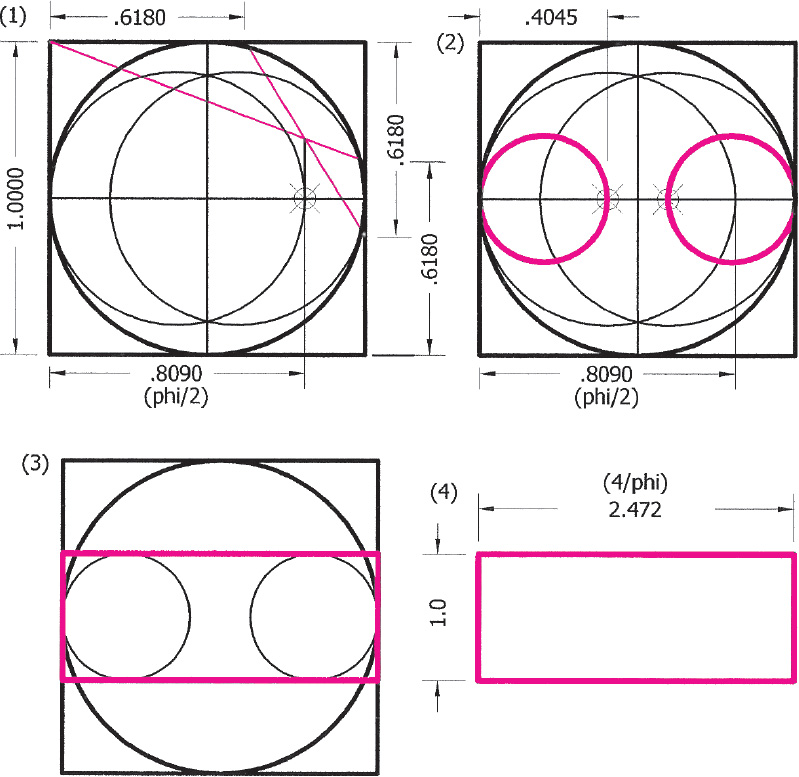

Drawing 6.1. The Earth-Sun octave construction, clockwise from bottom left, (1) shows us the construction of the 1/5 point on the string/diameter that we can then transfer to our main drawing, (2) in which a 64/109 diameter C2 circle is constructed. Through a sixfold octave reduction, (3) a circle is found that has the size of the Earth diameter in relation to the main enclosing circle that represents the Sun. In (4) the Earth circle is enlarged and shown in relation to a circumference arc of the Sun.

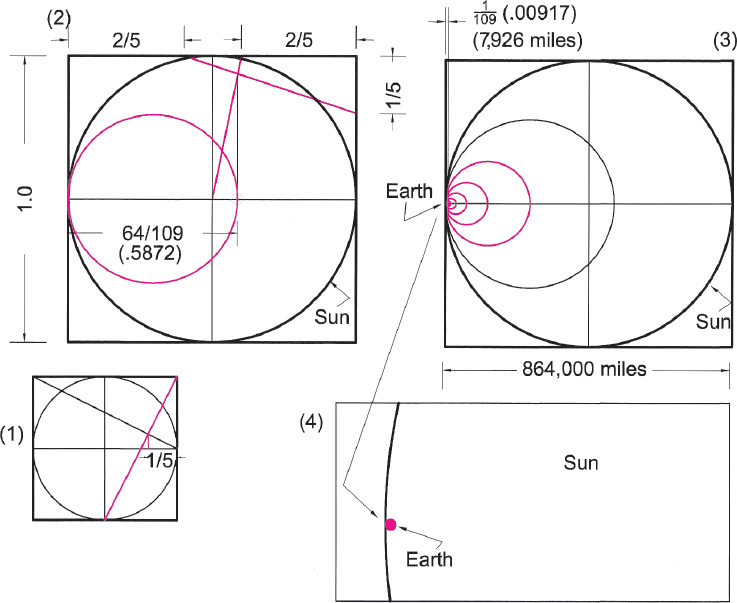

The 64/109 tone (.5872) is very close (within 99 percent) to the Pythagorean major sixth of 16/27 (.5925) ratio. Their difference is 108/109. If we were to substitute the Pythagorean ratio into our geometry, our octave halving would result in an Earth diameter of exactly 8,000 miles and a Sun/Earth ratio of 108:

864,000 miles ÷ 8,000 miles = 108.

With these round numbers we seem to have entered the realm of the archetypal, of Plato’s world of perfect Forms symbolized by simple integral ratios, pure tones, and straightforward geometry.

THE SKY SPEAKS

The Sun number of 864 is the octave of 432, which is within the main doubling-generated octave 256–512. In this octave, 432, which is at the Pythagorean-sixth interval position of 16/27—that is, 256/432 = 16/27—we can get an insight into the harmonic nature of the imperial (mile/foot) system of measure.

The Pythagorean-sixth interval position of 432 is also the octave of 216 (2 × 108), the Moon number, the Moon diameter being 2,160 miles, and 216 × 2 = 432. Thus, our “ideal Earth” of 8,000 miles, our Sun of 864,000 miles, and our Moon of 2,160 miles all fit into a seamless harmonic system. It is interesting that the measured Earth of 7,926 miles must be perfected or idealized so as to fit into this cosmic system. Perhaps this is the heavenly message to us—that we, as co-creators, must bring the Earth to a state of cosmic perfection in order to harmonize with the Universe. All these small discrepancies, or “commas,” that arise in our harmonic studies remind me of the refrain from Leonard Cohen’s song “Anthem”: “There is a crack in everything / that’s how the light gets in.”

Drawing 6.2. The octave construction of the “ideal Earth” on the face of the Sun. In (1–2) the Pythagorean-sixth vesica construction is made. In (3–4) octave circles are located resulting in an Earth circle 108th the size of the Sun circle, or, in actual measurement, 8,000 miles.

Let us look more closely at this discrepancy, or “comma.” The difference between the measured Earth (7,926) and the ideal Earth (8,000) is 74 miles. An interesting number results when we divide 8,000 by 74:

8,000 miles ÷ 74 miles = 108.108108,

which mysteriously yet obviously emphasizes the importance of this number 108.

The reciprocal of 74 equals 1/74, which, when brought into the main octave, is 1/74, 1/37, 2/37, 4/37, 8/37, 16/37, 32/37—and

32 ÷ 37 = .864864, the Sun number repeated.

Also, let us consider the reciprocal of the ideal 108 Sun/Earth ratio that we can superimpose on the ideal Earth:

1/108 × 8,000 miles = 74+ miles (74.074).

The physical result of this experiment would be a circular area of 74 miles diameter, representing the Sun, located on Earth. Interestingly, the measured Earth equals the ideal Earth minus the Sun reciprocal: 8,000 miles − 74 miles = 7,926 miles, as if to say that the way to bring Earth into perfection somehow lies with the Sun—perhaps the honoring of the Sun in the manner of ancient civilizations or changing our energy systems to solar power.

Let us apply our Sun/Earth reciprocal to the Moon. Our Earth/Sun reciprocal circle of 74 miles fits within the diameter of the Moon 29.19 times—very close to the 29.53 number of days in a lunation: 2,160 miles ÷ 74 miles = 29.19 miles.

Again we encounter a small discrepancy, or comma, between the calculated and the real. In this case the difference between 29.53 and 29.19 is about a syntonic comma of 80/81, the same little interval that we have used to transform Pythagorean intervals to just-intonation intervals. Thus 81/80 × 29.19 = 29.55, which is within 99 percent of the 29.53 lunation period.

*

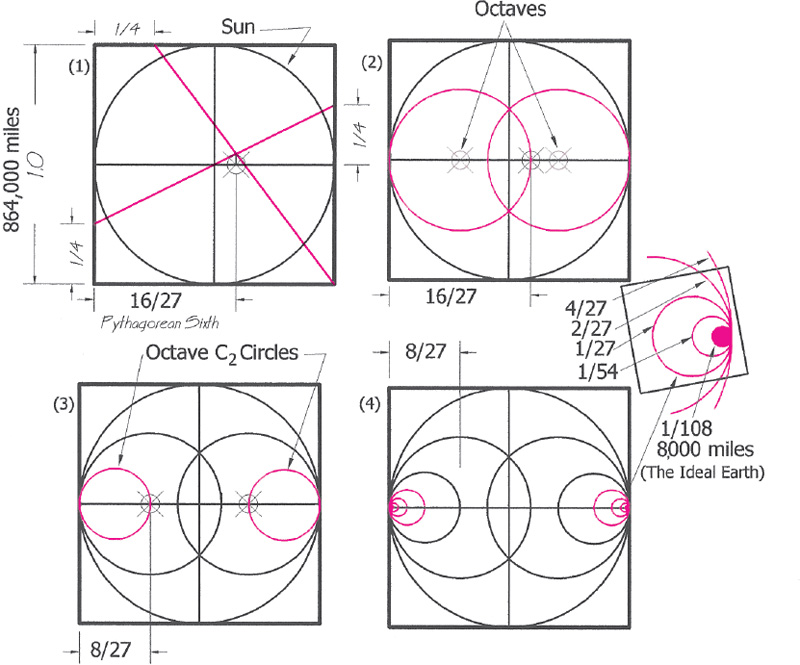

But we have digressed from our themes of octave and spiral. Because the use of ϕ-family ratios as generating tones in our constructions generally result in harmonious figures, we have used ϕ-based octave constructions in drawings 6.3 and 6.4 to construct figures related to our now familiar 4/ϕ number that we first encountered in the Apollo temple ratio.

Drawing 6.3. Using the octave construction at the ϕ tritone, a subtle ellipse with length-to-width ratio of 17/18 is produced within a context filled with harmonious relationships. (1) The vesica-generating circles are halved—that is, they are at the octave of the generating tone of .691 since .691/2 = .3455. (2) The centers of the octave circles are joined with the vesica poles to produce an ellipse. In (3) we see the ellipse in relation to the containing circle. Their area relation is 4/ϕ, our now familiar Apollo temple ratio. In (4) the ellipse is enclosed in a rectangle with ratio of 17/18, the string-length ratio of an Arabic semitone. This design could be the plan for a harmonic garden.

Drawing 6.4. (1) At the .809 (ϕ/2) point on the string/ diameter a vesica is constructed. (2) Then two octave circles are drawn. (3) and (4) The rectangle joining them has a ratio of 4/ϕ or 2.472, the ground-plan ratio of the Apollo temple described in chapter 2.

OCTAVE SPIRALS

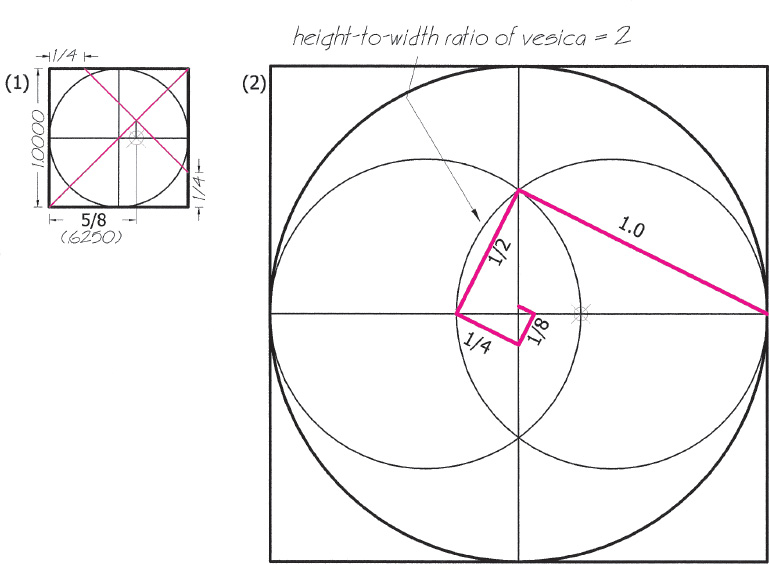

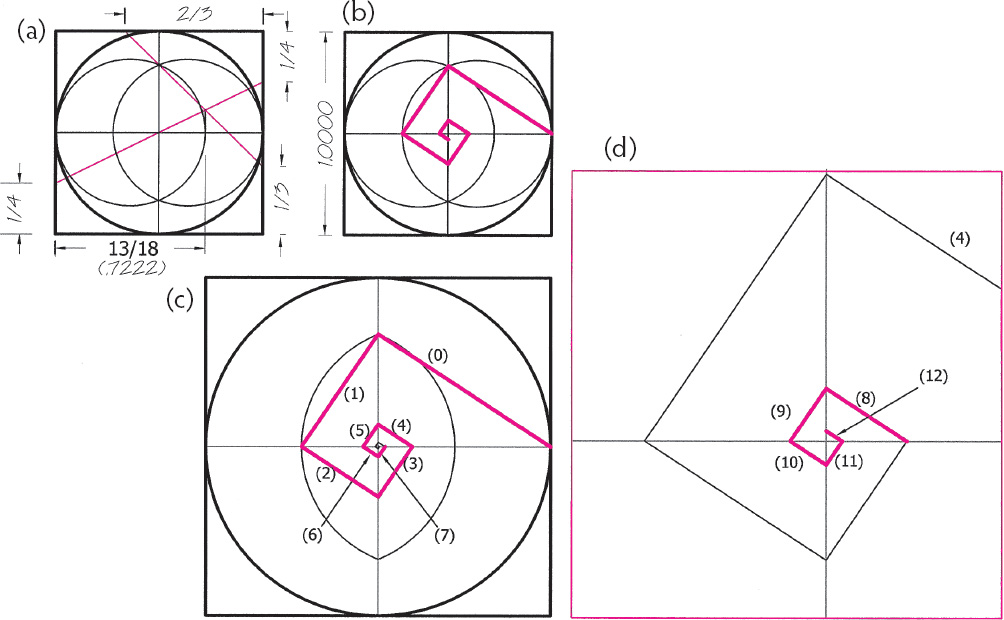

We have seen how the vesica-construction matrix is able to generate octaves of the fundamental tone. There is another way we can geometrically express octaves with the vesica construction. This is by using the vesica spiral as shown in drawing 6.5. The height-to-width ratio of the vesica determines the ratio of the progression of this straight-line spiral. Thus, in our example we have constructed a vesica with the ratio of 2 from our minor sixth tone. The segments of the straight-line spiral are in 2-to-1 ratio, the ratio of the octave. In our second example (drawing 6.6) the ratio of the vesica is 1.5, which is the frequency ratio of the perfect fifth with string length of 2/3 (.667) of the musical string. The spiral that we then construct contains a progression in which each tone segment is followed by a tone segment that is in a fifth relation to it. This is the ancient spiral of fifths that establishes the tones of the Pythagorean scale. In the process of unfolding twelve tones we traverse seven octaves. There is, however, a discrepancy, a comma, which becomes apparent when we transpose a number of the tones back to the main octave. Among these is the final tone just sharp of the octave by the fraction 73/74—the Pythagorean comma.

Drawing 6.5. (1) The minor sixth tone with string-length ratio of 5/8 is established. (2) The vesica construction at the minor sixth generates a vesica of height-to-width ratio of 2. A straight-line spiral is then constructed in which adjacent segment lengths are in the ratio of 2. Thus by considering the segments as string lengths we can visually get a sense of the pitch relationships of the successive octaves. We can do this procedure with any vesica: the vesica ratio will determine the progression of tones.

Drawing 6.6. The spiral of fifths. In (a) the 13/18 tritone (the inverse of the ϕ tritone of 9/13) is constructed generating a vesica with length-to-width ratio of 3/2, the frequency ratio of the fifth. This allows us to draw a spiral (b) whose successive segments, considered as musical strings, are in a fifth relation to one another. In the accompanying table are the segment-length ratios and their ratios when transposed and adjusted with the Pythagorean comma of 74/73 to the main octave. The result is the tones of the Pythagorean scale:

MUSICAL SPACES

As we have seen, an acceptance of the foot-mile system as valid cosmic measure is important for the understanding of this work. While it is true that the ratios between space and time measures, such as the ones we have been looking at, would be meaningful no matter what the measuring system, the presence of “canonical” mile measures, many of which are related to musical numbers, weaves the systems of harmonic science into a meaningful tapestry—a tapestry that lends color and life to the otherwise ascetic realm of dry number. The Sun number 864 (864,000 miles = Sun diameter) relates to the Moon number of 216 (2,160 miles = Moon diameter) through 4. This would be the same in any system, yet 864 is also a musical number, being an octave up from 432, a number prized by many musicians as an alternative to the A = 440 Hz standard. The 432 A relates to its fundamental of 256 through the Pythagorean-sixth interval of a 16/27 string length—that is, 256/432 = 16/27. It makes sense that 432, the Sun radius number, would set the tone in a meaningful solar system. Although we relate these numbers now to the modern cycles-per-second system, the numbers themselves served the harmonic arts in ancient times. The doubling geometric progression series 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512 was well known to the ancients, and they used it to form their musical intervals. They combined the doubled numbers with the tripling geometric series 1, 3, 9, 27, 81, 243, 729 to define the tones of the Pythagorean scale. As we previously noted, when multiples of 5 were included in the numerical toolbox, certain musical ratios became simpler—that is, they could be composed of smaller numbers: thus the Pythagorean 16/27 becomes 3/5 in just intonation. The “5-limit” numbers, though welcome simplifications of interval ratios, unfortunately have obscured the cosmic associations of the Pythagorean ratios such as we have seen with the Pythagorean sixth.

Here is an interesting aspect of our Sun number 864, which John Michell calls the foundation number. He writes: “In the language of symbolic number 864 clearly pertains to a center of radiant energy, the sun in the solar system, Jerusalem on earth, the inner sanctuary of the temple, the altar within it, and the corner stone on which the whole edifice is founded.”1

The frequency number 864 may be used to create a Pythagorean scale. We begin by reducing 864 along with two of its permutations—namely, 486 and 648—to their tones: 864 is within the 512–1,024 octave. Thus 512/864 = 16/27, the Pythagorean sixth. The number 486 is within the 256–512 octave: 256/486 = 128/243, the Pythagorean seventh. And 648, in the 512–1,024 octave, becomes 64/81, the Pythagorean third. Next we divide the third by the seventh, which equals 2/3, the fifth; and we divide the third by the sixth to give us 3/4, the fourth. Then the seventh is divided by the sixth to give us 8/9, the whole tone. The result is a seven-tone Pythagorean scale: 1, 8/9, 64/81, 3/4, 2/3, 16/27, 128/243.

Other important tones that are rare in practical music making include, as we noted earlier, the undecimal tones. We have seen in chapter 2 how the number 11 had an importance to the ancients rarely found in modern approaches to harmonic thought. In ancient times there were many undecimal tones in use, particularly in the Arabic world: an 11/16 (3¼) tone; an 11/18 (4¼) tone; a 6/11 Arabic neutral seventh that we used in drawing 2.1 to generate the 11/1 Jupiter-to-Earth diameter ratio; an 11/12 tone used on the Arabic lute, which is a tone that refers to the Earth/Sun ratio: 792/864 = 11/12; a 10/11 whole tone cited by Ptolemy; a 22/27 tone of the eighth-century musician Zalzal, whose octaves 11/27, 11/54, 11/108, 11/216, 11/432 are composed of Moon and Sun numbers (see drawing 6.7).

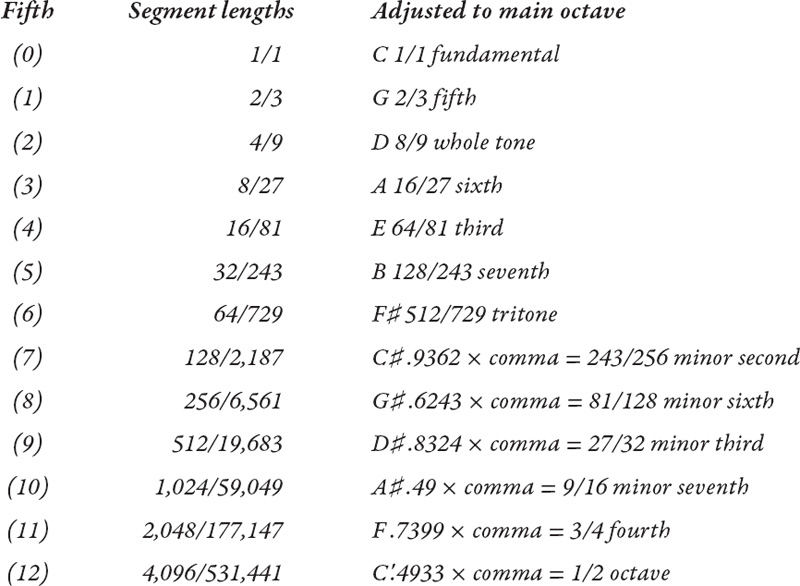

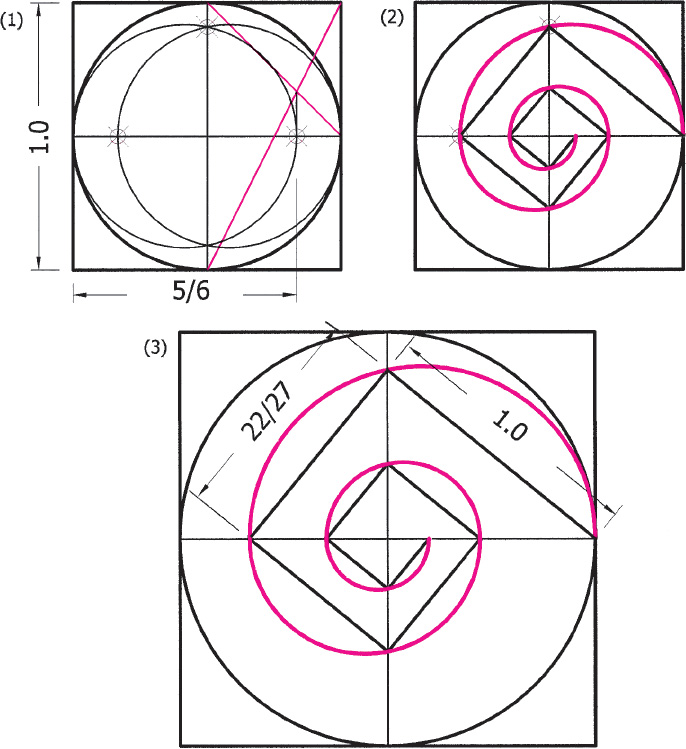

Drawing 6.7. The construction of a spiral whose ratio equals the tone known as the “Wosta of Zalzal.” (1) A minor 3rd diagonal construction generates a vesica with the ratio (within 99%) of 27/22 (1.2272). (2) A straight line spiral whose adjacent segments are in the ratio of 22/27 is constructed. A three-point circle arc spiral is constructed on the straight-line spiral. (3) The finished spiral showing the tonal relationship. The Wosta of Zalzal is named after its creator, Mansur Zalzal, an Arabic musician of the early ninth century. The string-length ratio, 22/27 (.8148), is called a “neutral third.”

The spiral form that we have been considering is the gesture of the octave progression as its tone spirals inward, sounding higher and higher pitches during its journey within the realm of vibration. We can imagine this form in three dimensions like a spiral staircase as it recedes from sight into the regions where the tones can only be detected by the most sensitive instruments. And still the spiral keeps winding into the realm of unimaginably high pitches.

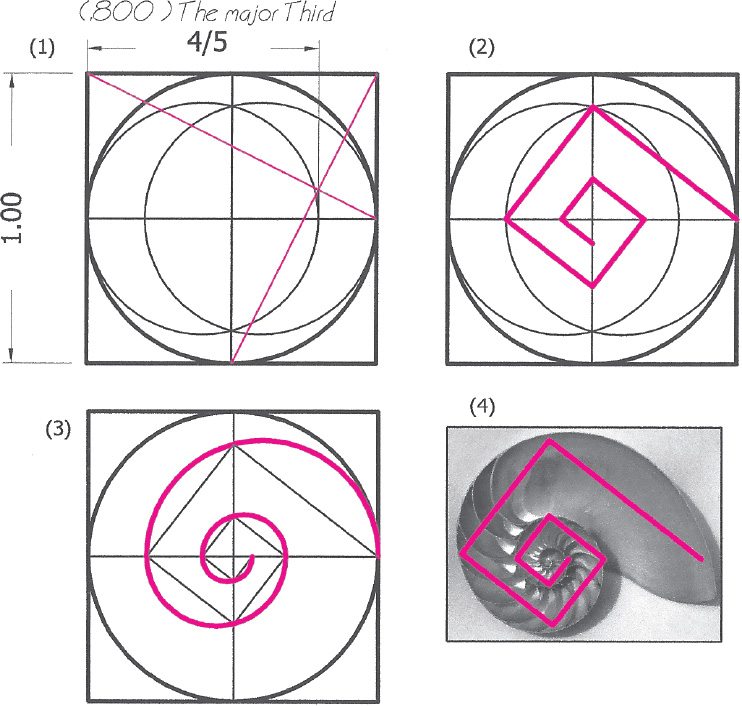

Drawing 6.8. (1) The vesica construction at the major third uses crossed diagonals to establish the 4/5 (.80) tonal point. (2) A straight-line spiral is constructed. The segments are in 1.291 ratio. (3) A spiral composed of three-point circle arcs is drawn. (4) This spiral approximates the logarithmic spiral of the nautilus.

Figure 6A. Pictured here are (a) Nautilus shell; (b) Begonia ‘Duartei’ leaf; and (c) spiral galaxy M74. Regarding the spiral, A. S. Eddington wrote: “The form of the arms—a logarithmic spiral—has not yet given any clue to the dynamics of the spiral nebulae. But though we do not understand the cause we see that there is a widespread law compelling matter to flow in these forms.” A.S Eddington2

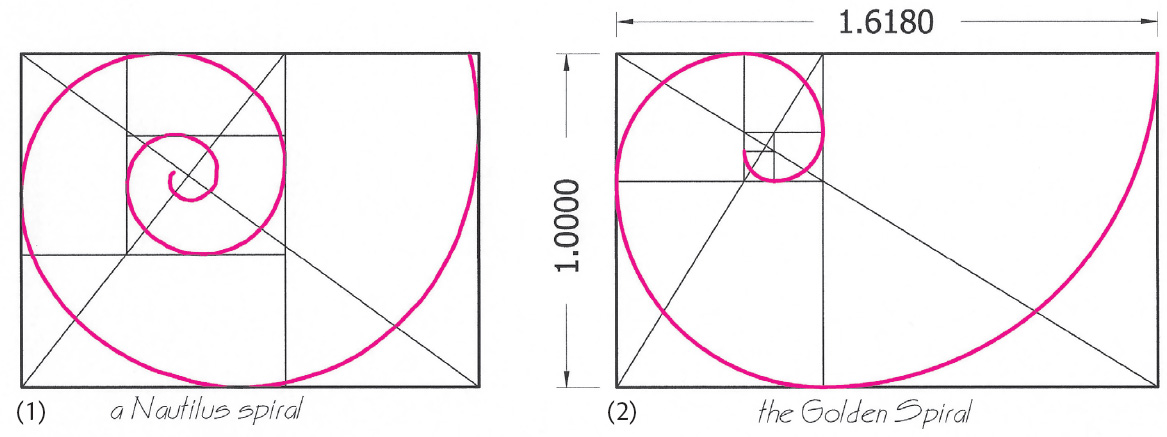

There is one spiral that can be constructed with circle arcs rather than spiral ve arcs. This is the golden spiral, an archetypal logarithmic spiral that can be constructed with classical geometry—that is, with lines and circles. Drawing 6.9 shows the golden spiral alongside a spiral drawn from points on the border of a nautilus shell.

Drawing 6.9. Two spirals, (1) one produced from points along the edge of a nautilus shell, (2) the other the golden spiral constructed from circle arcs. These are examples of gnomonic growth. The gnomon is a figure that, when added to an original figure, generates a new figure with the same proportion as the original. With the golden rectangle, shown on the right, the gnomon is a square that, when added to a golden rectangle, results in another golden rectangle. Thus the shape of the golden rectangle consists of a spiral of squares. The same gnomonic principle applies to all logarithmic spirals (such as the nautilus spiral): each spiral can be analyzed by a spiraling succession of rectangles of equal ratio.