Chapter 14. Expressions and Control Flow in JavaScript

In the previous chapter, I introduced the basics of JavaScript and the DOM. Now it’s time to look at how to construct complex expressions in JavaScript and how to control the program flow of your scripts by using conditional statements.

Expressions

JavaScript expressions are very similar to those in PHP. As you learned in Chapter 4, an expression is a combination of values, variables, operators, and functions that results in a value; the result can be a number, a string, or a Boolean value (which evaluates to either true or false).

Example 14-1 shows some simple expressions. For each line, it prints out a letter between a and d, followed by a colon and the result of the expressions. The <br> tag is there to create a line break and separate the output into four lines (remember that both <br> and <br /> are acceptable in HTML5, so I chose to use the former style for brevity).

Example 14-1. Four simple Boolean expressions

<script>

document.write("a: " + (42 > 3) + "<br>")

document.write("b: " + (91 < 4) + "<br>")

document.write("c: " + (8 == 2) + "<br>")

document.write("d: " + (4 < 17) + "<br>")

</script>

The output from this code is as follows:

a: true b: false c: false d: true

Notice that both expressions a: and d: evaluate to true. But b: and c: evaluate to false. Unlike PHP (which would print the number 1 and nothing, respectively), actual strings of true and false are displayed.

In JavaScript, when you are checking whether a value is true or false, all values evaluate to true except the following, which evaluate to false: the string false itself, 0, –0, the empty string, null, undefined, and NaN (Not a Number, a computer engineering concept for an illegal floating-point operation such as division by zero).

Note how I am referring to true and false in lowercase. This is because, unlike in PHP, these values must be in lowercase in JavaScript. Therefore, only the first of the two following statements will display, printing the lowercase word true, because the second will cause a 'TRUE' is not defined error:

if (1 == true) document.write('true') // True

if (1 == TRUE) document.write('TRUE') // Will cause an error

Note

Remember that any code snippets you wish to type and try for yourself in an HTML file need to be enclosed within <script> and </script> tags.

Literals and Variables

The simplest form of an expression is a literal, which means something that evaluates to itself, such as the number 22 or the string Press Enter. An expression could also be a variable, which evaluates to the value that has been assigned to it. They are both types of expressions, because they return a value.

Example 14-2 shows three different literals and two variables, all of which return values, albeit of different types.

Example 14-2. Five types of literals

<script>

myname = "Peter"

myage = 24

document.write("a: " + 42 + "<br>") // Numeric literal

document.write("b: " + "Hi" + "<br>") // String literal

document.write("c: " + true + "<br>") // Constant literal

document.write("d: " + myname + "<br>") // String variable

document.write("e: " + myage + "<br>") // Numeric variable

</script>

And, as you’d expect, you see a return value from all of these in the following output:

a: 42 b: Hi c: true d: Peter e: 24

Operators let you create more-complex expressions that evaluate to useful results. When you combine assignment or control-flow constructs with expressions, the result is a statement.

Example 14-3 shows one of each. The first assigns the result of the expression 366 - day_number to the variable days_to_new_year, and the second outputs a friendly message only if the expression days_to_new_year < 30 evaluates to true.

Example 14-3. Two simple JavaScript statements

<script>

days_to_new_year = 366 - day_number;

if (days_to_new_year < 30) document.write("It's nearly New Year")

</script>

Operators

JavaScript offers a lot of powerful operators that range from arithmetic, string, and logical operators to assignment, comparison, and more (see Table 14-1).

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic | Basic mathematics | a + b |

| Array | Array manipulation | a + b |

| Assignment | Assign values | a = b + 23 |

| Bitwise | Manipulate bits within bytes | 12 ^ 9 |

| Comparison | Compare two values | a < b |

| Increment/decrement | Add or subtract one | a++ |

| Logical | Boolean | a && b |

| String | Concatenation | a + 'string' |

Each operator takes a different number of operands:

-

Unary operators, such as incrementing (

a++) or negation (-a), take a single operand. -

Binary operators, which represent the bulk of JavaScript operators—including addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—take two operands.

-

One ternary operator, which takes the form

? x : y. It’s a terse single-lineifstatement that chooses between two expressions depending on a third one.

Operator Precedence

As with PHP, JavaScript utilizes operator precedence, in which some operators in an expression are considered more important than others and are therefore evaluated first. Table 14-2 lists JavaScript’s operators and their precedencies.

| Operator(s) | Type(s) |

|---|---|

() [] . |

Parentheses, call, and member |

++ -- |

Increment/decrement |

+ - ~ ! |

Unary, bitwise, and logical |

* / % |

Arithmetic |

+ - |

Arithmetic and string |

<< >> >>> |

Bitwise |

< > <= >= |

Comparison |

== != === !== |

Comparison |

& ^ | |

Bitwise |

&& |

Logical |

|| |

Logical |

? : |

Ternary |

= += -= *= /= %= |

Assignment |

<<= >>= >>>= &= ^= |= |

Assignment |

, |

Separator |

Associativity

Most JavaScript operators are processed in order from left to right in an equation. But some operators require processing from right to left instead. The direction of processing is called the operator’s associativity.

This associativity becomes important in cases where you do not explicitly force precedence. For example, look at the following assignment operators, by which three variables are all set to the value 0:

level = score = time = 0

This multiple assignment is possible only because the rightmost part of the expression is evaluated first and then processing continues in a right-to-left direction. Table 14-3 lists operators and their associativity.

| Operator | Description | Associativity |

|---|---|---|

++ -- |

Increment and decrement | None |

new |

Create a new object | Right |

+ - ~ ! |

Unary and bitwise | Right |

?: |

Ternary | Right |

= *= /= %= += -= |

Assignment | Right |

<<= >>= >>>= &= ^= |= |

Assignment | Right |

, |

Separator | Left |

+ - * / % |

Arithmetic | Left |

<< >> >>> |

Bitwise | Left |

< <= > >= == != === !== |

Arithmetic | Left |

Relational Operators

Relational operators test two operands and return a Boolean result of either true or false. There are three types of relational operators: equality, comparison, and logical.

Equality operators

The equality operator is == (which should not be confused with the = assignment operator). In Example 14-4, the first statement assigns a value, and the second tests it for equality. As it stands, nothing will be printed out, because month is assigned the string value July, and therefore the check for it having a value of October will fail.

Example 14-4. Assigning a value and testing for equality

<script>

month = "July"

if (month == "October") document.write("It's the Fall")

</script>

If the two operands of an equality expression are of different types, JavaScript will convert them to whatever type makes best sense to it. For example, any strings composed entirely of numbers will be converted to numbers whenever compared with a number. In Example 14-5, a and b are two different values (one is a number and the other is a string), and we would therefore normally expect neither of the if statements to output a result.

Example 14-5. The equality and identity operators

<script>

a = 3.1415927

b = "3.1415927"

if (a == b) document.write("1")

if (a === b) document.write("2")

</script>

However, if you run the example, you will see that it outputs the number 1, which means that the first if statement evaluated to true. This is because the string value of b was first temporarily converted to a number, and therefore both halves of the equation had a numerical value of 3.1415927.

In contrast, the second if statement uses the identity operator, three equals signs in a row, which prevents JavaScript from automatically converting types. This means that a and b are therefore found to be different, so nothing is output.

As with forcing operator precedence, whenever you’re in doubt about how JavaScript will convert operand types, you can use the identity operator to turn this behavior off.

Comparison operators

Using comparison operators, you can test for more than just equality and inequality. JavaScript also gives you > (is greater than), < (is less than), >= (is greater than or equal to), and <= (is less than or equal to) to play with. Example 14-6 shows these operators in use.

Example 14-6. The four comparison operators

<script>

a = 7; b = 11

if (a > b) document.write("a is greater than b<br>")

if (a < b) document.write("a is less than b<br>")

if (a >= b) document.write("a is greater than or equal to b<br>")

if (a <= b) document.write("a is less than or equal to b<br>")

</script>

In this example, where a is 7 and b is 11, the following is output (because 7 is less than 11, and also less than or equal to 11):

a is less than b a is less than or equal to b

Logical operators

Logical operators produce true-or-false results, and are also known as Boolean operators. There are three of them in JavaScript (see Table 14-4).

| Logical operator | Description |

|---|---|

&& |

true if both operands are true |

|| |

true if either operand is true |

! |

true if the operand is false, or false if the operand is true |

You can see how these can be used in Example 14-7, which outputs 0, 1, and true.

Example 14-7. The logical operators in use

<script> a = 1; b = 0 document.write((a && b) + "<br>") document.write((a || b) + "<br>") document.write(( !b ) + "<br>") </script>

The && statement requires both operands to be true if it is going to return a value of true, the || statement will be true if either value is true, and the third statement performs a NOT on the value of b, turning it from 0 into a value of true.

The || operator can cause unintentional problems, because the second operand will not be evaluated if the first is evaluated as true. In Example 14-8, the getnext function will never be called if finished has a value of 1.

Example 14-8. A statement using the || operator

<script> if (finished == 1 || getnext() == 1) done = 1 </script>

If you need getnext to be called at each if statement, you should rewrite the code as shown in Example 14-9.

Example 14-9. The if...or statement modified to ensure calling of getnext

<script> gn = getnext() if (finished == 1 OR gn == 1) done = 1; </script>

In this case, the code in function getnext will be executed and its return value stored in gn before the if statement.

Table 14-5 shows all the possible variations of using the logical operators. You should also note that !true equals false, and !false equals true.

| Inputs | Operators and results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

A |

b |

&& |

|| |

true |

true |

true |

true |

true |

false |

false |

true |

false |

true |

false |

true |

false |

false |

false |

false |

The with Statement

The with statement is not one that you’ve seen in earlier chapters on PHP, because it’s exclusive to JavaScript. With it (if you see what I mean), you can simplify some types of JavaScript statements by reducing many references to an object to just one reference. References to properties and methods within the with block are assumed to apply to that object.

For example, take the code in Example 14-10, in which the document.write function never references the variable string by name.

Example 14-10. Using the with statement

<script>

string = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog"

with (string)

{

document.write("The string is " + length + " characters<br>")

document.write("In upper case it's: " + toUpperCase())

}

</script>

Even though string is never directly referenced by document.write, this code still manages to output the following:

The string is 43 characters In upper case it's: THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG

This is how the code works: the JavaScript interpreter recognizes that the length property and toUpperCase() method have to be applied to some object. Because they stand alone, the interpreter assumes they apply to the string object that you specified in the with statement.

Using onerror

There are more constructs not available in PHP. Using either the onerror event, or a combination of the try and catch keywords, you can catch JavaScript errors and deal with them yourself.

Events are actions that can be detected by JavaScript. Every element on a web page has certain events that can trigger JavaScript functions. For example, the onclick event of a button element can be set to call a function and make it run whenever a user clicks the button.

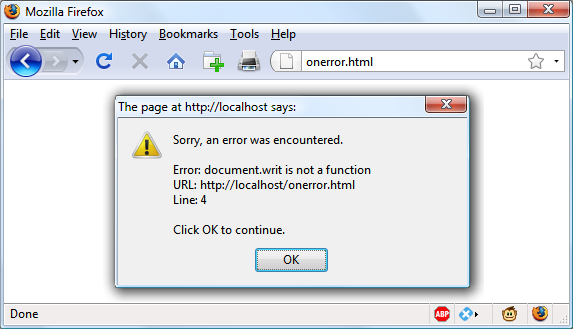

Example 14-11 illustrates how to use the onerror event.

Example 14-11. A script employing the onerror event

<script>

onerror = errorHandler

document.writ("Welcome to this website") // Deliberate error

function errorHandler(message, url, line)

{

out = "Sorry, an error was encountered.\n\n";

out += "Error: " + message + "\n";

out += "URL: " + url + "\n";

out += "Line: " + line + "\n\n";

out += "Click OK to continue.\n\n";

alert(out);

return true;

}

</script>

The first line of this script tells the error event to use the new errorHandler function from now onward. This function takes three parameters—a message, a url, and a line number—so it’s a simple matter to display all these in an alert pop up.

Then, to test the new function, we deliberately place a syntax error in the code with a call to document.writ instead of document.write (the final e is missing). Figure 14-1 shows the result of running this script in a browser. Using onerror this way can also be quite useful during the debugging process.

Figure 14-1. Using the onerror event with an alert method pop-up

Using try...catch

The try and catch keywords are more standard and more flexible than the onerror technique shown in the previous section. These keywords let you trap errors for a selected section of code, rather than all scripts in a document. However, they do not catch syntax errors, for which you need onerror.

The try...catch construct is supported by all major browsers and is handy when you want to catch a certain condition that you are aware could occur in a specific part of your code.

For example, in Chapter 17 we’ll be exploring Ajax techniques that make use of the XMLHttpRequest object. Unfortunately, this isn’t available in the Internet Explorer browser (although it is in all other major browsers). Therefore, we can use try and catch to trap this case and do something else if the function is not available. Example 14-12 shows how.

Example 14-12. Trapping an error with try and catch

<script>

try

{

request = new XMLHTTPRequest()

}

catch(err)

{

// Use a different method to create an XML HTTP Request object

}

</script>

I won’t go into how we implement the missing object in Internet Explorer here, but you can see how the system works. There’s also another keyword associated with try and catch called finally that is always executed, regardless of whether an error occurs in the try clause. To use it, just add something like the following statements after a catch statement:

finally

{

alert("The 'try' clause was encountered")

}

Conditionals

Conditionals alter program flow. They enable you to ask questions about certain things and respond to the answers you get in different ways. There are three types of nonlooping conditionals: the if statement, the switch statement, and the ? operator.

The if Statement

Several examples in this chapter have already made use of if statements. The code within such a statement is executed only if the given expression evaluates to true. Multiline if statements require curly braces around them, but as in PHP, you can omit the braces for single statements. Therefore, the following statements are valid:

if (a > 100)

{

b=2

document.write("a is greater than 100")

}

if (b == 10) document.write("b is equal to 10")

The else Statement

When a condition has not been met, you can execute an alternative by using an else statement, like this:

if (a > 100)

{

document.write("a is greater than 100")

}

else

{

document.write("a is less than or equal to 100")

}

Unlike PHP, JavaScript has no elseif statement, but that’s not a problem, because you can use an else followed by another if to form the equivalent of an elseif statement, like this:

if (a > 100)

{

document.write("a is greater than 100")

}

else if(a < 100)

{

document.write("a is less than 100")

}

else

{

document.write("a is equal to 100")

}

As you can see, you can use another else after the new if, which could equally be followed by another if statement, and so on. Although I have shown braces on the statements, because each is a single line, the whole previous example could be written as follows:

if (a > 100) document.write("a is greater than 100")

else if(a < 100) document.write("a is less than 100")

else document.write("a is equal to 100")

The switch Statement

The switch statement is useful when one variable or the result of an expression can have multiple values, and you want to perform a different function for each value.

For example, the following code takes the PHP menu system we put together in Chapter 4 and converts it to JavaScript. It works by passing a single string to the main menu code according to what the user requests. Let’s say the options are Home, About, News, Login, and Links, and we set the variable page to one of these according to the user’s input.

The code for this written using if...else if... might look like Example 14-13.

Example 14-13. A multiline if...else if... statement

<script>

if (page == "Home") document.write("You selected Home")

else if (page == "About") document.write("You selected About")

else if (page == "News") document.write("You selected News")

else if (page == "Login") document.write("You selected Login")

else if (page == "Links") document.write("You selected Links")

</script>

But using a switch construct, the code could look like Example 14-14.

Example 14-14. A switch construct

<script>

switch (page)

{

case "Home":

document.write("You selected Home")

break

case "About":

document.write("You selected About")

break

case "News":

document.write("You selected News")

break

case "Login":

document.write("You selected Login")

break

case "Links":

document.write("You selected Links")

break

}

</script>

The variable page is mentioned only once at the start of the switch statement. Thereafter, the case command checks for matches. When one occurs, the matching conditional statement is executed. Of course, a real program would have code here to display or jump to a page, rather than simply telling the user what was selected.

Breaking out

As you can see in Example 14-14, just as with PHP, the break command allows your code to break out of the switch statement once a condition has been satisfied. Remember to include the break unless you want to continue executing the statements under the next case.

Default action

When no condition is satisfied, you can specify a default action for a switch statement by using the default keyword. Example 14-15 shows a code snippet that could be inserted into Example 14-14.

Example 14-15. A default statement to add to Example 14-14

default:

document.write("Unrecognized selection")

break

The ? Operator

The ternary operator (?), combined with the : character, provides a quick way of doing if...else tests. With it you can write an expression to evaluate, and then follow it with a ? symbol and the code to execute if the expression is true. After that, place a : and the code to execute if the expression evaluates to false.

Example 14-16 shows a ternary operator being used to print out whether the variable a is less than or equal to 5, and prints something either way.

Example 14-16. Using the ternary operator

<script>

document.write(

a <= 5 ?

"a is less than or equal to 5" :

"a is greater than 5"

)

</script>

The statement has been broken up into several lines for clarity, but you would be more likely to use such a statement on a single line, in this manner:

size = a <= 5 ? "short" : "long"

Looping

Again, you will find many close similarities between JavaScript and PHP when it comes to looping. Both languages support while, do...while, and for loops.

while Loops

A JavaScript while loop first checks the value of an expression and starts executing the statements within the loop only if that expression is true. If it is false, execution skips over to the next JavaScript statement (if any).

Upon completing an iteration of the loop, the expression is again tested to see if it is true, and the process continues until such a time as the expression evaluates to false or until execution is otherwise halted. Example 14-17 shows such a loop.

Example 14-17. A while loop

<script>

counter=0

while (counter < 5)

{

document.write("Counter: " + counter + "<br>")

++counter

}

</script>

This script outputs the following:

Counter: 0 Counter: 1 Counter: 2 Counter: 3 Counter: 4

Warning

If the variable counter were not incremented within the loop, it is quite possible that some browsers could become unresponsive due to a never-ending loop, and the page may not even be easy to terminate with Escape or the Stop button. So be careful with your JavaScript loops.

do...while Loops

When you require a loop to iterate at least once before any tests are made, use a do...while loop, which is similar to a while loop, except that the test expression is checked only after each iteration of the loop. So, to output the first seven results in the 7 times table, you could use code such as that in Example 14-18.

Example 14-18. A do...while loop

<script>

count = 1

do

{

document.write(count + " times 7 is " + count * 7 + "<br>")

} while (++count <= 7)

</script>

As you might expect, this loop outputs the following:

1 times 7 is 7 2 times 7 is 14 3 times 7 is 21 4 times 7 is 28 5 times 7 is 35 6 times 7 is 42 7 times 7 is 49

for Loops

A for loop combines the best of all worlds into a single looping construct that allows you to pass three parameters for each statement:

-

An initialization expression

-

A condition expression

-

A modification expression

These are separated by semicolons, like this: for (expr1 ; expr2 ; expr3). At the start of the first iteration of the loop, the initialization expression is executed. In the case of the code for the multiplication table for 7, count would be initialized to the value 1. Then, each time around the loop, the condition expression (in this case, count <= 7) is tested, and the loop is entered only if the condition is true. Finally, at the end of each iteration, the modification expression is executed. In the case of the multiplication table for 7, the variable count is incremented. Example 14-19 shows what the code would look like.

Example 14-19. Using a for loop

<script>

for (count = 1 ; count <= 7 ; ++count)

{

document.write(count + "times 7 is " + count * 7 + "<br>");

}

</script>

As in PHP, you can assign multiple variables in the first parameter of a for loop by separating them with a comma, like this:

for (i = 1, j = 1 ; i < 10 ; i++)

Likewise, you can perform multiple modifications in the last parameter, like this:

for (i = 1 ; i < 10 ; i++, --j)

Or you can do both at the same time:

for (i = 1, j = 1 ; i < 10 ; i++, --j)

Breaking Out of a Loop

The break command, which you’ll recall is important inside a switch statement, is also available within for loops. You might need to use this, for example, when searching for a match of some kind. Once the match is found, you know that continuing to search will only waste time and make your visitor wait. Example 14-20 shows how to use the break command.

Example 14-20. Using the break command in a for loop

<script>

haystack = new Array()

haystack[17] = "Needle"

for (j = 0 ; j < 20 ; ++j)

{

if (haystack[j] == "Needle")

{

document.write("<br>- Found at location " + j)

break

}

else document.write(j + ", ")

}

</script>

This script outputs the following:

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, - Found at location 17

The continue Statement

Sometimes you don’t want to entirely exit from a loop, but instead wish to skip the remaining statements just for this iteration of the loop. In such cases, you can use the continue command. Example 14-21 shows this in use.

Example 14-21. Using the continue command in a for loop

<script>

haystack = new Array()

haystack[4] = "Needle"

haystack[11] = "Needle"

haystack[17] = "Needle"

for (j = 0 ; j < 20 ; ++j)

{

if (haystack[j] == "Needle")

{

document.write("<br>- Found at location " + j + "<br>")

continue

}

document.write(j + ", ")

}

</script>

Notice how the second document.write call does not have to be enclosed in an else statement (as it did before), because the continue command will skip it if a match has been found. The output from this script is as follows:

0, 1, 2, 3, - Found at location 4 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, - Found at location 11 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, - Found at location 17 18, 19,

Explicit Casting

Unlike PHP, JavaScript has no explicit casting of types such as (int) or (float). Instead, when you need a value to be of a certain type, use one of JavaScript’s built-in functions, shown in Table 14-6.

| Change to type | Function to use |

|---|---|

| Int, Integer | parseInt() |

| Bool, Boolean | Boolean() |

| Float, Double, Real | parseFloat() |

| String | String() |

| Array | split() |

So, for example, to change a floating-point number to an integer, you could use code such as the following (which displays the value 3):

n = 3.1415927 i = parseInt(n) document.write(i)

Or you can use the compound form:

document.write(parseInt(3.1415927))

That’s it for control flow and expressions. The next chapter focuses on the use of functions, objects, and arrays in JavaScript.

Questions

- How are Boolean values handled differently by PHP and JavaScript?

- What characters are used to define a JavaScript variable name?

- What is the difference between unary, binary, and ternary operators?

- What is the best way to force your own operator precedence?

- When would you use the

===(identity) operator? - What are the simplest two forms of expressions?

- Name the three conditional statement types.

- How do

ifandwhilestatements interpret conditional expressions of different data types? - Why is a

forloop more powerful than awhileloop? - What is the purpose of the

withstatement?

See Chapter 14 Answers in Appendix A for the answers to these questions.