Chapter 16. JavaScript and PHP Validation and Error Handling

With your solid foundation in both PHP and JavaScript, it’s time to bring these technologies together to create web forms that are as user-friendly as possible.

We’ll be using PHP to create the forms and JavaScript to perform client-side validation to ensure that the data is as complete and correct as it can be before it is submitted. Final validation of the input will then be made by PHP, which will, if necessary, present the form again to the user for further modification.

In the process, this chapter will cover validation and regular expressions in both JavaScript and PHP.

Validating User Input with JavaScript

JavaScript validation should be considered an assistance more to your users than to your websites because, as I have already stressed many times, you cannot trust any data submitted to your server, even if it has supposedly been validated with JavaScript. This is because hackers can quite easily simulate your web forms and submit any data of their choosing.

Another reason you cannot rely on JavaScript to perform all your input validation is that some users disable JavaScript, or use browsers that don’t support it.

So the best types of validation to do in JavaScript are checking that fields have content if they are not to be left empty, ensuring that email addresses conform to the proper format, and ensuring that values entered are within expected bounds.

The validate.html Document (Part 1)

Let’s begin with a general sign-up form, common on most sites that offer memberships or registered users. The inputs requested will be forename, surname, username, password, age, and email address. Example 16-1 provides a good template for such a form.

Example 16-1. A form with JavaScript validation (part 1)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>An Example Form</title>

<style>

.signup {

border:1px solid #999999;

font: normal 14px helvetica;

color: #444444;

}

</style>

<script>

function validate(form)

{

fail = validateForename(form.forename.value)

fail += validateSurname(form.surname.value)

fail += validateUsername(form.username.value)

fail += validatePassword(form.password.value)

fail += validateAge(form.age.value)

fail += validateEmail(form.email.value)

if (fail == "") return true

else { alert(fail); return false }

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<table border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="5" bgcolor="#eeeeee">

<th colspan="2" align="center">Signup Form</th>

<form method="post" action="adduser.php" onsubmit="return validate(this)">

<tr><td>Forename</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="32" name="forename"></td></tr>

<tr><td>Surname</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="32" name="surname"></td></tr>

<tr><td>Username</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="16" name="username"></td></tr>

<tr><td>Password</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="12" name="password"></td></tr>

<tr><td>Age</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="3" name="age"></td></tr>

<tr><td>Email</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="64" name="email"></td></tr>

<tr><td colspan="2" align="center"><input type="submit"

value="Signup"></td></tr>

</form>

</table>

</body>

</html>

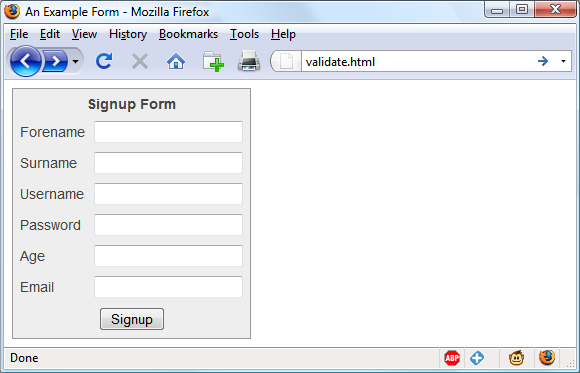

As it stands, this form will display correctly but will not self-validate, because the main validation functions have not yet been added. Even so, save it as validate.html, and when you call it up in your browser, it will look like Figure 16-1.

Figure 16-1. The output from Example 16-1

Let’s look at how this document is made up. The first few lines set up the document and use a little CSS to make the form look a little less plain. The parts of the document related to JavaScript come next and are shown in bold.

Between the <script> and </script> tags lies a single function called validate that itself calls up six other functions to validate each of the form’s input fields. We’ll get to these functions shortly. For now I’ll just explain that they return either an empty string if a field validates, or an error message if it fails. If there are any errors, the final line of the script pops up an alert box to display them.

Upon passing validation, the validate function returns a value of true; otherwise, it returns false. The return values from validate are important, because if it returns false, the form is prevented from being submitted. This allows the user to close the alert pop up and make changes. If true is returned, no errors were encountered in the form’s fields and so the form is allowed to be submitted.

The second part of this example features the HTML for the form with each field and its name placed within its own row of a table. This is pretty straightforward HTML, with the exception of the onSubmit="return validate(this)" statement within the opening <form> tag. Using onSubmit, you can cause a function of your choice to be called when a form is submitted. That function can perform some checking and return a value of either true or false to signify whether the form should be allowed to be submitted.

The this parameter is the current object (i.e., this form) and is passed to the validate function just discussed. The validate function receives this parameter as the object form.

As you can see, the only JavaScript used within the form’s HTML is the call to return buried in the onSubmit attribute. Browsers with JavaScript disabled or not available will simply ignore the onSubmit attribute, and the HTML will display just fine.

The validate.html Document (Part 2)

Now we come to Example 16-2, a set of six functions that do the actual form-field validation. I suggest that you type all of this second part and save it in the <script>...</script> section of Example 16-1, which you should already have saved as validate.html.

Example 16-2. A form with JavaScript validation (part 2)

function validateForename(field)

{

return (field == "") ? "No Forename was entered.\n" : ""

}

function validateSurname(field)

{

return (field == "") ? "No Surname was entered.\n" : ""

}

function validateUsername(field)

{

if (field == "") return "No Username was entered.\n"

else if (field.length < 5)

return "Usernames must be at least 5 characters.\n"

else if (/[^a-zA-Z0-9_-]/.test(field))

return "Only a-z, A-Z, 0-9, - and _ allowed in Usernames.\n"

return ""

}

function validatePassword(field)

{

if (field == "") return "No Password was entered.\n"

else if (field.length < 6)

return "Passwords must be at least 6 characters.\n"

else if (!/[a-z]/.test(field) || ! /[A-Z]/.test(field) ||

!/[0-9]/.test(field))

return "Passwords require one each of a-z, A-Z and 0-9.\n"

return ""

}

function validateAge(field)

{

if (isNaN(field)) return "No Age was entered.\n"

else if (field < 18 || field > 110)

return "Age must be between 18 and 110.\n"

return ""

}

function validateEmail(field)

{

if (field == "") return "No Email was entered.\n"

else if (!((field.indexOf(".") > 0) &&

(field.indexOf("@") > 0)) ||

/[^a-zA-Z0-9.@_-]/.test(field))

return "The Email address is invalid.\n"

return ""

}

We’ll go through each of these functions in turn, starting with validateForename, so you can see how validation works.

Validating the forename

validateForename is quite a short function that accepts the parameter field, which is the value of the forename passed to it by the validate function.

If this value is the empty string, an error message is returned; otherwise, an empty string is returned to signify that no error was encountered.

If the user entered spaces in this field, it would be accepted by validateForename, even though it’s empty for all intents and purposes. You can fix this by adding an extra statement to trim whitespace from the field before checking whether it’s empty, use a regular expression to make sure there’s something besides whitespace in the field, or—as I do here—just let the user make the mistake and allow the PHP program to catch it on the server.

Validating the surname

The validateSurname function is almost identical to validateForename in that an error is returned only if the surname supplied was an empty string. I chose not to limit the characters allowed in either of the name fields to allow for possibilities such as non-English and accented characters.

Validating the username

The validateUsername function is a little more interesting, because it has a more complicated job. It has to allow through only the characters a-z, A-Z, 0-9, _ and -, and ensure that usernames are at least five characters long.

The if...else statements commence by returning an error if field has not been filled in. If it’s not the empty string, but is fewer than five characters in length, another error message is returned.

Then the JavaScript test function is called, passing a regular expression (which matches any character that is not one of those allowed) to be matched against field (see “Regular Expressions”). If even one character that isn’t one of the acceptable characters is encountered, the test function returns true, and so validateUser returns an error string.

Validating the password

Similar techniques are used in the validatePassword function. First the function checks whether field is empty, and if it is, returns an error. Next, an error message is returned if a password is shorter than six characters.

One of the requirements we’re imposing on passwords is that they must have at least one each of a lowercase, uppercase, and numerical character, so the test function is called three times, once for each of these cases. If any one of them returns false, one of the requirements was not met and so an error message is returned. Otherwise, the empty string is returned to signify that the password was OK.

Validating the age

validateAge returns an error message if field is not a number (determined by a call to the isNaN function), or if the age entered is lower than 18 or greater than 110. Your applications may well have different or no age requirements. Again, upon successful validation, the empty string is returned.

Validating the email

In the last and most complicated example, the email address is validated with validateEmail. After checking whether anything was actually entered, and returning an error message if it wasn’t, the function calls the JavaScript indexOf function twice. The first time a check is made to ensure there is a period (.) somewhere from at least the second character of the field, and the second checks that an @ symbol appears somewhere at or after the second character.

If those two checks are satisfied, the test function is called to see whether any disallowed characters appear in the field. If any of these tests fail, an error message is returned. The allowed characters in an email address are uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and the _, -, period, and @ characters, as detailed in the regular expression passed to the test method. If no errors are found, the empty string is returned to indicate successful validation. On the last line, the script and document are closed.

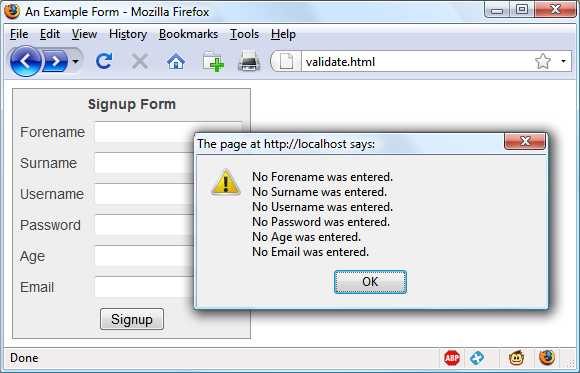

Figure 16-2 shows the result of the user clicking the Signup button without having completed any fields.

Figure 16-2. JavaScript form validation in action

Using a separate JavaScript file

Of course, because they are generic in construction and could apply to many types of validations you might require, these six functions make ideal candidates for moving out into a separate JavaScript file. You could name the file something like validate_functions.js and include it right after the initial script section in Example 16-1, using the following statement:

<script src="validate_functions.js"></script>

Regular Expressions

Let’s look a little more closely at the pattern matching we have been doing. We’ve achieved it using regular expressions, which are supported by both JavaScript and PHP. They make it possible to construct the most powerful of pattern-matching algorithms within a single expression.

Matching Through Metacharacters

Every regular expression must be enclosed in slashes. Within these slashes, certain characters have special meanings; they are called metacharacters. For instance, an asterisk (*) has a meaning similar to what you have seen if you use a shell or Windows command prompt (but not quite the same). An asterisk means, “The text you’re trying to match may have any number of the preceding characters—or none at all.”

For instance, let’s say you’re looking for the name Le Guin and know that someone might spell it with or without a space. Because the text is laid out strangely (for instance, someone may have inserted extra spaces to right-justify lines), you could have to search for a line such as this:

The difficulty of classifying Le Guin's works

So you need to match LeGuin, as well as Le and Guin separated by any number of spaces. The solution is to follow a space with an asterisk:

/Le *Guin/

There’s a lot more than the name Le Guin in the line, but that’s OK. As long as the regular expression matches some part of the line, the test function returns a true value. What if it’s important to make sure the line contains nothing but Le Guin? I’ll show you how to ensure that later.

Suppose that you know there is always at least one space. In that case, you could use the plus sign (+), because it requires at least one of the preceding characters to be present:

/Le +Guin/

Fuzzy Character Matching

The dot (.) is particularly useful, because it can match anything except a newline. Suppose that you are looking for HTML tags, which start with < and end with >. A simple way to do so is shown here:

/<.*>/

The dot matches any character, and the * expands it to match zero or more characters, so this is saying, “Match anything that lies between < and >, even if there’s nothing.” You will match <>, <em>, <br>, and so on. But if you don’t want to match the empty case, <>, you should use + instead of *, like this:

/<.+>/

The plus sign expands the dot to match one or more characters, saying, “Match anything that lies between < and > as long as there’s at least one character between them.” You will match <em> and </em>, <h1> and </h1>, and tags with attributes, such as this:

<a href="www.mozilla.org">

Unfortunately, the plus sign keeps on matching up to the last > on the line, so you might end up with this:

<h1><b>Introduction</b></h1>

A lot more than one tag! I’ll show a better solution later in this section.

Note

If you use the dot on its own between the angle brackets, without following it with either a + or *, then it matches a single character; you will match <b> and <i> but not <em> or <textarea>.

If you want to match the dot character itself (.), you have to escape it by placing a backslash (\) before it, because otherwise it’s a metacharacter and matches anything. As an example, suppose you want to match the floating-point number 5.0. The regular expression is as follows:

/5\.0/

The backslash can escape any metacharacter, including another backslash (in case you’re trying to match a backslash in text). However, to make things a bit confusing, you’ll see later how backslashes sometimes give the following character a special meaning.

We just matched a floating-point number. But perhaps you want to match 5. as well as 5.0, because both mean the same thing as a floating-point number. You also want to match 5.00, 5.000, and so forth—any number of zeros is allowed. You can do this by adding an asterisk, as you’ve seen:

/5\.0*/

Grouping Through Parentheses

Suppose you want to match powers of increments of units, such as kilo, mega, giga, and tera. In other words, you want all the following to match:

1,000 1,000,000 1,000,000,000 1,000,000,000,000 ...

The plus sign works here, too, but you need to group the string ,000 so the plus sign matches the whole thing. The regular expression is as follows:

/1(,000)+ /

The parentheses mean “treat this as a group when you apply something such as a plus sign.” 1,00,000 and 1,000,00 won’t match because the text must have a 1 followed by one or more complete groups of a comma followed by three zeros.

The space after the + character indicates that the match must end when a space is encountered. Without it, 1,000,00 would incorrectly match because only the first 1,000 would be taken into account, and the remaining ,00 would be ignored. Requiring a space afterward ensures that matching will continue right through to the end of a number.

Character Classes

Sometimes you want to match something fuzzy, but not so broad that you want to use a dot. Fuzziness is the great strength of regular expressions: they allow you to be as precise or vague as you want.

One of the key features supporting fuzzy matching is the pair of square brackets, []. It matches a single character, like a dot, but inside the brackets you put a list of things that can match. If any of those characters appears, the text matches. For instance, if you wanted to match both the American spelling gray and the British spelling grey, you could specify the following:

/gr[ae]y/

After the gr in the text you’re matching, there can be either an a or an e. But there must be only one of them: whatever you put inside the brackets matches exactly one character. The group of characters inside the brackets is called a character class.

Indicating a Range

Inside the brackets, you can use a hyphen (-) to indicate a range. One very common task is matching a single digit, which you can do with a range as follows:

/[0-9]/

Digits are such a common item in regular expressions that a single character is provided to represent them: \d. You can use it in place of the bracketed regular expression to match a digit:

/\d/

Negation

One other important feature of the square brackets is negation of a character class. You can turn the whole character class on its head by placing a caret (^) after the opening bracket. Here it means, “Match any characters except the following.” So let’s say you want to find instances of Yahoo that lack the following exclamation point. (The name of the company officially contains an exclamation point!) You could do it as follows:

/Yahoo[^!]/

The character class consists of a single character—an exclamation point—but it is inverted by the preceding ^. This is actually not a great solution to the problem—for instance, it fails if Yahoo is at the end of the line, because then it’s not followed by anything, whereas the brackets must match a character. A better solution involves negative lookahead (matching something that is not followed by anything else), but that’s beyond the scope of this book.

Some More-Complicated Examples

With an understanding of character classes and negation, you’re ready now to see a better solution to the problem of matching an HTML tag. This solution avoids going past the end of a single tag, but still matches tags such as <em> and </em> as well as tags with attributes such as this:

<a href="www.mozilla.org">

Here is one solution:

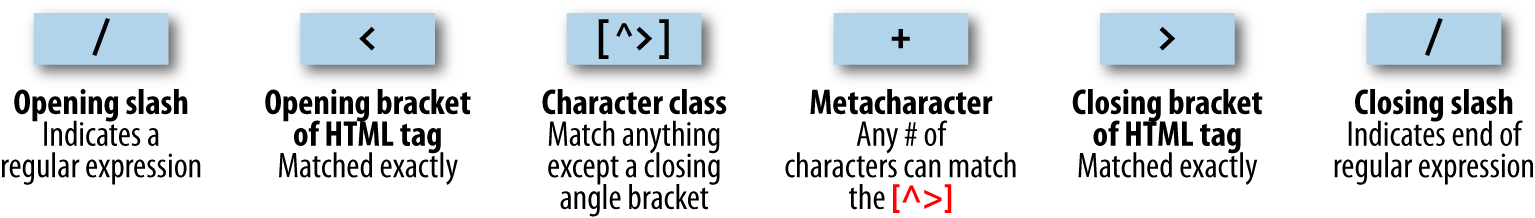

/<[^>]+>/

That regular expression may look like I just dropped my teacup on the keyboard, but it is perfectly valid and very useful. Let’s break it apart. Figure 16-3 shows the various elements, which I’ll describe one by one.

Figure 16-3. Breakdown of a typical regular expression

The elements are as follows:

/- Opening slash that indicates this is a regular expression.

<- Opening bracket of an HTML tag. This is matched exactly; it is not a metacharacter.

[^>]- Character class. The embedded

^>means “match anything except a closing angle bracket.” +- Allows any number of characters to match the previous

[^>], as long as there is at least one of them. >- Closing bracket of an HTML tag. This is matched exactly.

/- Closing slash that indicates the end of the regular expression.

Note

Another solution to the problem of matching HTML tags is to use a nongreedy operation. By default, pattern matching is greedy, returning the longest match possible. Nongreedy matching finds the shortest possible match, and its use is beyond the scope of this book, but there are more details at http://oreilly.com/catalog/regex/chapter/ch04.html.

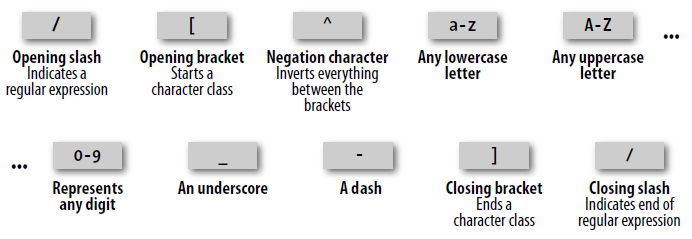

We are going to look now at one of the expressions from Example 16-1, where the validateUsername function is used:

/[^a-zA-Z0-9_-]/

Figure 16-4 shows the various elements.

Figure 16-4. Breakdown of the validateUsername regular expression

Let’s look at these elements in detail:

/- Opening slash that indicates this is a regular expression.

[- Opening bracket that starts a character class.

^- Negation character: inverts everything else between the brackets.

a-z- Represents any lowercase letter.

A-Z- Represents any uppercase letter.

0-9- Represents any digit.

_- An underscore.

-- A dash.

]- Closing bracket that ends a character class.

/- Closing slash that indicates the end of the regular expression.

There are two other important metacharacters. They “anchor” a regular expression by requiring that it appear in a particular place. If a caret (^) appears at the beginning of the regular expression, the expression has to appear at the beginning of a line of text; otherwise, it doesn’t match. Similarly, if a dollar sign ($) appears at the end of the regular expression, the expression has to appear at the end of a line of text.

Note

It may be somewhat confusing that ^ can mean “negate the character class” inside square brackets and “match the beginning of the line” if it’s at the beginning of the regular expression. Unfortunately, the same character is used for two different things, so take care when using it.

We’ll finish our exploration of regular expression basics by answering a question raised earlier: suppose you want to make sure there is nothing extra on a line besides the regular expression? What if you want a line that has “Le Guin” and nothing else? We can do that by amending the earlier regular expression to anchor the two ends:

/^Le *Guin$/

Summary of Metacharacters

Table 16-1 shows the metacharacters available in regular expressions.

| Metacharacters | Description |

|---|---|

/ |

Begins and ends the regular expression |

. |

Matches any single character except the newline |

|

Matches element zero or more times |

|

Matches element one or more times |

|

Matches element zero or one times |

[ |

Matches a character out of those contained within the brackets |

[^ |

Matches a single character that is not contained within the brackets |

( |

Treats the regex as a group for counting or a following *, +, or ? |

|

Matches either left or right |

[ |

Matches a range of characters between l and r |

^ |

Requires match to be at the string’s start |

$ |

Requires match to be at the string’s end |

\b |

Matches a word boundary |

\B |

Matches where there is not a word boundary |

\d |

Matches a single digit |

\D |

Matches a single nondigit |

\n |

Matches a newline character |

\s |

Matches a whitespace character |

\S |

Matches a nonwhitespace character |

\t |

Matches a tab character |

\w |

Matches a word character (a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and _) |

\W |

Matches a nonword character (anything but a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and _) |

\ |

x (useful if x is a metacharacter, but you really want x) |

{ |

Matches exactly n times |

{ |

Matches n times or more |

{ |

Matches at least min and at most max times |

Provided with this table, and looking again at the expression /[^a-zA-Z0-9_]/, you can see that it could easily be shortened to /[^\w]/ because the single metacharacter \w (with a lowercase w) specifies the characters a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and _.

In fact, we can be cleverer than that, because the metacharacter \W (with an uppercase W) specifies all characters except for a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and _. Therefore, we could also drop the ^ metacharacter and simply use /[\W]/ for the expression.

To give you more ideas of how this all works, Table 16-2 shows a range of expressions and the patterns they match.

| Example | Matches |

|---|---|

r |

The first r in The quick brown |

rec[ei][ei]ve |

Either of receive or recieve (but also receeve or reciive) |

rec[ei]{2}ve |

Either of receive or recieve (but also receeve or reciive) |

rec(ei|ie)ve |

Either of receive or recieve (but not receeve or reciive) |

cat |

The word cat in I like cats and dogs |

cat|dog |

Either of the words cat or dog in I like cats and dogs |

\. |

. (the \ is necessary because . is a metacharacter) |

5\.0* |

5., 5.0, 5.00, 5.000, etc. |

[a-f] |

Any of the characters a, b, c, d, e or f |

cats$ |

Only the final cats in My cats are friendly cats |

^my |

Only the first my in my cats are my pets |

\d{2,3} |

Any two- or three-digit number (00 through 999) |

7(,000)+ |

7,000; 7,000,000; 7,000,000,000; 7,000,000,000,000; etc. |

[\w]+ |

Any word of one or more characters |

[\w]{5} |

Any five-letter word |

General Modifiers

Some additional modifiers are available for regular expressions:

-

/genables global matching. When using a replace function, specify this modifier to replace all matches, rather than only the first one. -

/imakes the regular expression match case-insensitive. Thus, instead of/[a-zA-Z]/, you could specify/[a-z]/ior/[A-Z]/i. -

/menables multiline mode, in which the caret (^) and dollar ($) match before and after any newlines in the subject string. Normally, in a multiline string,^matches only at the start of the string, and$matches only at the end of the string.

For example, the expression /cats/g will match both occurrences of the word cats in the sentence I like cats, and cats like me. Similarly, /dogs/gi will match both occurrences of the word dogs (Dogs and dogs) in the sentence Dogs like other dogs, because you can use these specifiers together.

Using Regular Expressions in JavaScript

In JavaScript, you will use regular expressions mostly in two methods: test (which you have already seen) and replace. Whereas test just tells you whether its argument matches the regular expression, replace takes a second parameter: the string to replace the text that matches. Like most functions, replace generates a new string as a return value; it does not change the input.

To compare the two methods, the following statement just returns true to let us know that the word cats appears at least once somewhere within the string:

document.write(/cats/i.test("Cats are funny. I like cats."))

But the following statement replaces both occurrences of the word cats with the word dogs, printing the result. The search has to be global (/g) to find all occurrences, and case-insensitive (/i) to find the capitalized Cats:

document.write("Cats are friendly. I like cats.".replace(/cats/gi,"dogs"))

If you try out the statement, you’ll see a limitation of replace: because it replaces text with exactly the string you tell it to use, the first word Cats is replaced by dogs instead of Dogs.

Using Regular Expressions in PHP

The most common regular expression functions that you are likely to use in PHP are preg_match, preg_match_all, and preg_replace.

To test whether the word cats appears anywhere within a string, in any combination of upper- and lowercase, you could use preg_match like this:

$n = preg_match("/cats/i", "Cats are crazy. I like cats.");

Because PHP uses 1 for TRUE and 0 for FALSE, the preceding statement sets $n to 1. The first argument is the regular expression, and the second is the text to match. But preg_match is actually a good deal more powerful and complicated, because it takes a third argument that shows what text matched:

$n = preg_match("/cats/i", "Cats are curious. I like cats.", $match);

echo "$n Matches: $match[0]";

The third argument is an array (here, given the name $match). The function puts the text that matches into the first element, so if the match is successful, you can find the text that matched in $match[0]. In this example, the output lets us know that the matched text was capitalized:

1 Matches: Cats

If you wish to locate all matches, you use the preg_match_all function, like this:

$n = preg_match_all("/cats/i", "Cats are strange. I like cats.", $match);

echo "$n Matches: ";

for ($j=0 ; $j < $n ; ++$j) echo $match[0][$j]." ";

As before, $match is passed to the function and the element $match[0] is assigned the matches made, but this time as a subarray. To display the subarray, this example iterates through it with a for loop.

When you want to replace part of a string, you can use preg_replace as shown here. This example replaces all occurrences of the word cats with the word dogs, regardless of case:

echo preg_replace("/cats/i", "dogs", "Cats are furry. I like cats.");

Note

The subject of regular expressions is a large one, and entire books have been written about it. If you would like further information, I suggest the Wikipedia entry, or Jeffrey Friedl’s excellent book Mastering Regular Expressions.

Redisplaying a Form After PHP Validation

OK, back to form validation. So far we’ve created the HTML document validate.html, which will post through to the PHP program adduser.php, but only if JavaScript validates the fields or if JavaScript is disabled or unavailable.

So now it’s time to create adduser.php to receive the posted form, perform its own validation, and then present the form again to the visitor if the validation fails. Example 16-3 contains the code that you should type and save (or download from the companion website).

Example 16-3. The adduser.php program

<?php // adduser.php

// The PHP code

$forename = $surname = $username = $password = $age = $email = "";

if (isset($_POST['forename']))

$forename = fix_string($_POST['forename']);

if (isset($_POST['surname']))

$surname = fix_string($_POST['surname']);

if (isset($_POST['username']))

$username = fix_string($_POST['username']);

if (isset($_POST['password']))

$password = fix_string($_POST['password']);

if (isset($_POST['age']))

$age = fix_string($_POST['age']);

if (isset($_POST['email']))

$email = fix_string($_POST['email']);

$fail = validate_forename($forename);

$fail .= validate_surname($surname);

$fail .= validate_username($username);

$fail .= validate_password($password);

$fail .= validate_age($age);

$fail .= validate_email($email);

echo "<!DOCTYPE html>\n<html><head><title>An Example Form</title>";

if ($fail == "")

{

echo "</head><body>Form data successfully validated:

$forename, $surname, $username, $password, $age, $email.</body></html>";

// This is where you would enter the posted fields into a database,

// preferably using hash encryption for the password.

exit;

}

echo <<<_END

<!-- The HTML/JavaScript section -->

<style>

.signup {

border: 1px solid #999999;

font: normal 14px helvetica; color:#444444;

}

</style>

<script>

function validate(form)

{

fail = validateForename(form.forename.value)

fail += validateSurname(form.surname.value)

fail += validateUsername(form.username.value)

fail += validatePassword(form.password.value)

fail += validateAge(form.age.value)

fail += validateEmail(form.email.value)

if (fail == "") return true

else { alert(fail); return false }

}

function validateForename(field)

{

return (field == "") ? "No Forename was entered.\n" : ""

}

function validateSurname(field)

{

return (field == "") ? "No Surname was entered.\n" : ""

}

function validateUsername(field)

{

if (field == "") return "No Username was entered.\n"

else if (field.length < 5)

return "Usernames must be at least 5 characters.\n"

else if (/[^a-zA-Z0-9_-]/.test(field))

return "Only a-z, A-Z, 0-9, - and _ allowed in Usernames.\n"

return ""

}

function validatePassword(field)

{

if (field == "") return "No Password was entered.\n"

else if (field.length < 6)

return "Passwords must be at least 6 characters.\n"

else if (!/[a-z]/.test(field) || ! /[A-Z]/.test(field) ||

!/[0-9]/.test(field))

return "Passwords require one each of a-z, A-Z and 0-9.\n"

return ""

}

function validateAge(field)

{

if (isNaN(field)) return "No Age was entered.\n"

else if (field < 18 || field > 110)

return "Age must be between 18 and 110.\n"

return ""

}

function validateEmail(field)

{

if (field == "") return "No Email was entered.\n"

else if (!((field.indexOf(".") > 0) &&

(field.indexOf("@") > 0)) ||

/[^a-zA-Z0-9.@_-]/.test(field))

return "The Email address is invalid.\n"

return ""

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<table border="0" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="5" bgcolor="#eeeeee">

<th colspan="2" align="center">Signup Form</th>

<tr><td colspan="2">Sorry, the following errors were found<br>

in your form: <p><font color=red size=1><i>$fail</i></font></p>

</td></tr>

<form method="post" action="adduser.php" onSubmit="return validate(this)">

<tr><td>Forename</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="32" name="forename" value="$forename">

</td></tr><tr><td>Surname</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="32" name="surname" value="$surname">

</td></tr><tr><td>Username</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="16" name="username" value="$username">

</td></tr><tr><td>Password</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="12" name="password" value="$password">

</td></tr><tr><td>Age</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="3" name="age" value="$age">

</td></tr><tr><td>Email</td>

<td><input type="text" maxlength="64" name="email" value="$email">

</td></tr><tr><td colspan="2" align="center"><input type="submit"

value="Signup"></td></tr>

</form>

</table>

</body>

</html>

_END;

// The PHP functions

function validate_forename($field)

{

return ($field == "") ? "No Forename was entered<br>": "";

}

function validate_surname($field)

{

return($field == "") ? "No Surname was entered<br>" : "";

}

function validate_username($field)

{

if ($field == "") return "No Username was entered<br>";

else if (strlen($field) < 5)

return "Usernames must be at least 5 characters<br>";

else if (preg_match("/[^a-zA-Z0-9_-]/", $field))

return "Only letters, numbers, - and _ in usernames<br>";

return "";

}

function validate_password($field)

{

if ($field == "") return "No Password was entered<br>";

else if (strlen($field) < 6)

return "Passwords must be at least 6 characters<br>";

else if (!preg_match("/[a-z]/", $field) ||

!preg_match("/[A-Z]/", $field) ||

!preg_match("/[0-9]/", $field))

return "Passwords require 1 each of a-z, A-Z and 0-9<br>";

return "";

}

function validate_age($field)

{

if ($field == "") return "No Age was entered<br>";

else if ($field < 18 || $field > 110)

return "Age must be between 18 and 110<br>";

return "";

}

function validate_email($field)

{

if ($field == "") return "No Email was entered<br>";

else if (!((strpos($field, ".") > 0) &&

(strpos($field, "@") > 0)) ||

preg_match("/[^a-zA-Z0-9.@_-]/", $field))

return "The Email address is invalid<br>";

return "";

}

function fix_string($string)

{

if (get_magic_quotes_gpc()) $string = stripslashes($string);

return htmlentities ($string);

}

?>

Note

In this example, all input is sanitized prior to use, even passwords, which—since they may contain characters used to format HTML—will be changed into HTML entities. For example, & will become & and < will become <, and so on. If you will be using a hash function to store encrypted passwords, this will not be an issue as long as when you later check the password entered, it is sanitized in the same way, so that the same inputs will be compared.

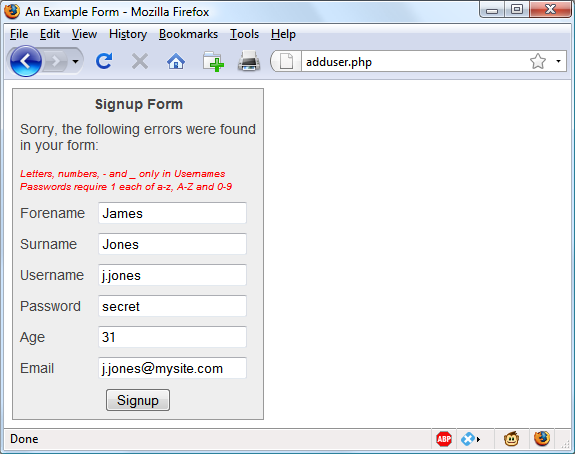

The result of submitting the form with JavaScript disabled (and two fields incorrectly completed) is shown in Figure 16-5.

Figure 16-5. The form as represented after PHP validation fails

I have put the PHP section of this code (and changes to the HTML section) in a bold typeface so that you can more clearly see the difference between this and Example 16-1 and Example 16-2.

If you browsed through this example (or typed it or downloaded it from the http://lpmj.net website), you’ll have seen that the PHP code is almost a clone of the JavaScript code; the same regular expressions are used to validate each field in very similar functions.

But there are a couple of things to note. First, the fix_string function (right at the end) is used to sanitize each field and prevent any attempts at code injection from succeeding.

Also, you will see that the HTML from Example 16-1 has been repeated in the PHP code within a <<<_END..._END; structure, displaying the form with the values that the visitor entered the previous time. You do this by simply adding an extra value parameter to each <input> tag (such as value="$forename"). This courtesy is highly recommended so that the user has to edit only the previously entered values, and doesn’t have to type the fields all over again.

Note

In the real world, you probably wouldn’t start with an HTML form such as the one in Example 16-1. Instead, you’d be more likely to go straight ahead and write the PHP program in Example 16-3, which incorporates all the HTML. And, of course, you’d also need to make a minor tweak for the case when it’s the first time the program is called up, to prevent it from displaying errors when all the fields are empty. You also might drop the six JavaScript functions into their own .js file for separate inclusion.

Now that you’ve seen how to bring all of PHP, HTML, and JavaScript together, the next chapter will introduce Ajax (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML), which uses JavaScript calls to the server in the background to seamlessly update portions of a web page, without having to resubmit the entire page to the web server.

Questions

- What JavaScript method can you use to send a form for validation prior to submitting it?

- What JavaScript method is used to match a string against a regular expression?

- Write a regular expression to match any characters that are not in a word, as defined by regular expression syntax.

- Write a regular expression to match either of the words fox or fix.

- Write a regular expression to match any single word followed by any nonword character.

- Using regular expressions, write a JavaScript function to test whether the word fox exists in the string

The quick brown fox. - Using regular expressions, write a PHP function to replace all occurrences of the word the in

The cow jumps over the moonwith the word my. - What HTML attribute is used to precomplete form fields with a value?

See Chapter 16 Answers in Appendix A for the answers to these questions.