Writing Your Family History

Please can I start writing my story now? I hear you say. Almost now, I reply. First, a word of warning. Whatever you do, don’t be too ambitious in what you set out to achieve. Aim to write a succinct story; if it grows as you go along, that’s fine, but don’t set yourself an impossible task at the beginning. The world is full of unfinished PhD theses. Many a student on a PhD course spends the first year gathering information far and wide, planning a thesis which is totally unrealistic in scope; the second year might then be spent in total despair, and the third in planning an exquisite and suitable suicide. Be warned - keep it manageable from the outset!

So. You’ve seized the day and rejected all excuses. Your decisions have been made. You’ve done your research and some background reading. You know which ancestral line you will follow. You know whether you will tell the story forwards or backwards. You’ve prepared a chronological set of notes on your family’s affairs set within a framework of local and national events, and you have a pedigree to work from. You’ll tackle the overall project in terms of smaller units such as cameos. You’ve decided whether to feature concurrent or consecutive lives.

You are now like a decorator who has carried out the laborious preparation necessary before the real job begins - you’ve stripped the window-frames of old paint and slapped on a coat of primer. You are now ready to dip your brush into the can of gloss paint -the really creative stage has arrived.

I shall now delay you only long enough to suggest that there are two more decisions to make at this point, and these have to do with the writing process itself, rather than the planning stage, which is now safely behind us. After that, you’ll be relieved to hear, you can start writing in earnest.

Decisions

Who exactly are you writing the family story for?

Who are your intended readers? Are they members of your family? Other family historians? Historians in general? The world? Do try to be more specific than simply ‘the general public’.

In the days when I was a teacher of communication studies, we used to talk about an ‘awareness of audience’. That is, having decided upon your intended readership or audience, keep that audience constantly in mind as you write. Any piece of communication can only be judged to be good or bad, effective or ineffective, in terms of what it aims to do and who it aims to do it for. Do you aim to inform, educate and entertain? Only one or two of these, or all three?

As to audience, if you write for your immediate family, you can relax - even share a few in-jokes with them; if you write for a broader readership, you may choose to be slightly more formal.

How much do you assume that your readers already know about the arcane world of family history research? Have they heard of the Hearth Tax, do they understand the importance of Hardwicke’s Marriage Act, do they know what a Settlement Certificate was? If you write a statement like this :

I found great-great grandfather in the B.T.s, living in a peculiar

are your readers to suppose that he was a full-blown alcoholic, shacked up in some kind of commune?

Above all you should try to achieve an empathy with your readers - that is, try to feel what it is like for them to read your story when they don’t have the knowledge that you have, and, worse, may not share your passionate interest in the whole thing. Assume that they need to be won over, persuaded, by your infectious enthusiasm. Don’t bore them to death, don’t try to impress them with your erudition - but don’t patronise them and assume that they know nothing whatever. And, yes, if in doubt, do tell them all about the Hearth Tax, about Hardwicke and about a Settlement Certificate; if they already know, they’ll feel very pleased with themselves, and if they don’t know, they’ll be glad of the clarification.

Will you write as a story teller, or as a historian?

I am grateful to Terrick Fitzhugh’s excellent book, How To Write a Family History, for drawing to my attention the important distinction between the approaches taken by a ‘story teller’ and a ‘historian’. What is that distinction? The historian is apt to make historical judgements as he goes along - indeed, he would regard it as one of his primary functions to do so. Will you make value judgements as you tell the story of your ancestors? Will you criticise your male ancestors for their treatment of women? Will you castigate your forebears for galloping across the countryside in pursuit of a fox, for eating red meat, for not being concerned about the fate of the rainforests or the world’s stock of whales?

Someone once said that it’s easy to have 20-20 vision in retrospect. We can all make supercilious judgements after the event, with the wisdom of hindsight. What, after all, will our descendants make of us? The past, they say, is a different country - and so it is. Why not spare our ancestors the spotlight of anything approaching political correctness and its bedfellow, righteous indignation? Perhaps we have to accept that most of our forebears led their lives to the best of their ability, given the constraints of the historical period in which they lived?

My own view is that it isn’t helpful to make retrospective judgements on our ancestors, that we should accompany them on their journey through life, walk with them down the tunnel which constituted their existence, not knowing where it might lead or whether there would be light at the end or not. Share with them their ignorance as well as their knowledge. They may well not have known or suspected that war was about to break out, that the plague was soon to erupt, that they would lose five children in infancy. Just as you would aim to have empathy with the readers of your book, have empathy with your ancestors, too.

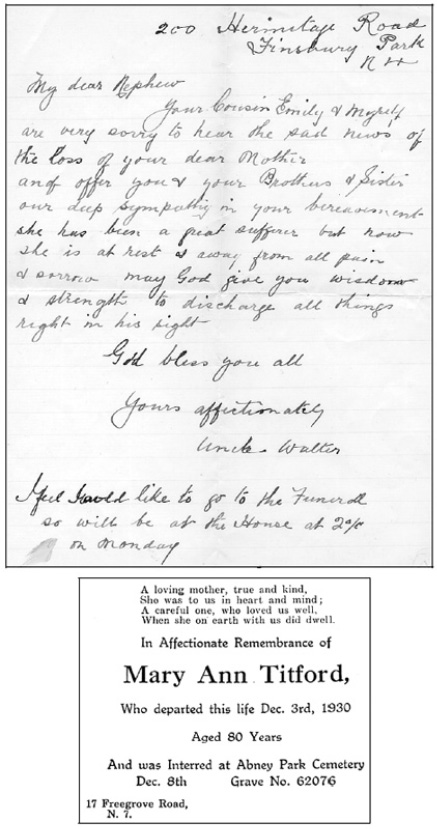

A bereavement would often generate correspondence which may have survived in a family archive. Typically there might be a ‘loving memory’ card (bottom) and/or a related letter of condolence (top).

A Funny Old Business

Let writing commence. To use an oxymoron, this is where the ‘satisfying slog’ begins.

To begin with, you may find that your creative energy - and you will certainly have some! - comes in fits and starts. Some days you will sit down to write and the words just won’t come out in the right way. You can’t turn fluency on like a tap, and if you’re tired, or your mind is on other things, there’ll be days when you creak your way through the writing process. There are two views on all this, and I won’t be prescriptive about which you will find most convincing. There are those who say that you should be disciplined in your approach, forcing yourself to sit down and write, say, for an hour each day, for a two-hour slot each week, or whatever. Others will maintain that there is little point in hitting your head against a brick wall if the words just won’t come; leave it for a while, wait until the creative muse is on top form, and sit down for a writing session whenever you feel the urge.

Whichever of these strategies you adopt, you really do need to be disciplined to some degree if you are ever to finish your task. Set yourself an overall deadline (‘I will have finished this family history two years from now’) and, if you can, short-term deadlines as well (‘I will have written two cameos by the end of next month’). Deadlines - and they should be realistic deadlines - focus the mind wonderfully; they will sometimes force you to keep going even when you don’t much feel like it (not always a bad thing) and they will probably persuade you that you’ll simply have to leave some things out of your story -that is, to edit. Also no bad thing! Some people work well under pressure, others don’t, but you must put at least some pressure on yourself if you are to write your family history. If you don’t, then Parkinson’s Law will operate, your time will be filled up with other things, and you’ll get nowhere. There will always be some task or other which you will have to lay aside if you are to do some serious writing.

If you allow everyday life to crowd out your writing time, then rest assured that it will do just that. You may even find that the time you spend being creative as a writer puts a certain amount of strain upon your relationship with your own family - which is why a number of books carry a dedication to the author’s husband, wife and/or children ‘for their patience and under-standing while this book was being written’. It’s really a matter of balance, isn’t it? No point in breaking your own present-day family asunder just to write a story of what your family got up to in the past!

So, I repeat, writing a book is a funny old business. You may even find that male authors will tell you that bringing their book to completion is the nearest thing a man can ever get to having a baby! Indeed, there are similarities - especially when, after months of patient work, it seems at times as if the book will never be finished, the birth will never happen. To me, one of the most aggravating things about writing a book occurs at the stage when I really do think that I’ve almost finished, that only a few things remain to be done. Just the introduction to write, the bibliography to compile, the illustrations to be chosen and captioned, the final proof-reading to be done, and so on. Maybe by that stage I’ve exhausted myself or allowed my creative energy to run low, but the last steps in the process of bringing a book to completion can be the most frustrating. Don’t let me put you off; it may not be like that for you!

One other thing will probably happen to you: your subconscious mind will be churning away a lot of the time, thinking about what you’ve already written and what you intend to write next. Flashes of inspiration may come to you when you’re driving the car, digging the garden, hanging out the washing, listening to a sermon or watching television. Don’t let such lashes sink down again into the nether regions; jot down a few notes on a piece of paper for future use - or use a small hand held tape recorder. If the bug really bites you, you might even wake up in the middle of the night and find yourself scrawling a note or two in case you’ve forgotten it by morning.

If stray ideas come to me while I’m busy typing the main text itself onto the computer, I very often skip to the end of the document I’m working on, make a few notes, and then return to where I was before.

Now, as a writer, you’re on your own - in more ways than one. You’ll probably need to find a quiet corner in which you can just sit and be madly creative, a place where you can spread books and papers all over the desk - and on the loor, of course -without anyone complaining too much. But you’re on your own in another way - that is, no one can tell you how to write as such. Teachers or helpful friends could give you a few hints regarding good style, could help out in specific matters of grammar, spelling and punctuation, but you will need to write in your own way -ideally in a manner which allows your own personality and view of the world to emerge. Do try to relax, to be yourself. I once had a car which never seemed to want to go into reverse gear; the more I tried to force the gear lever, the worse things became. The only way to persuade the lever into reverse was to make a conscious effort to relax, to stop tensing the muscles. Then it went in like a dream. And so it is with writing: it’s possible to try too hard, to strain every brain cell to the point where you can either write nothing at all, or what you do write seems stilted and strained. Try to relax as you write, enjoy yourself, take it easy, use a touch of humour and wit (without being flippant), try to entertain your readers, be bright, enthusiastic.

When it comes to the quality of your writing, there is a catch - a ‘Catch 22’, even. It works like this: the better you become at writing (and rest assured that you will, as time goes on), the higher the standards you will then set yourself for the future. This is one of life’s little cruelties, you might say, in this as in so many other fields of human activity. In other words, you can’t win . . .

Nuts and Bolts

I was once an English teacher, so without much prompting I could bore for England on the subject of grammar, spelling and punctuation. I’ll spare you most of that, suggesting instead that you refer to one of the many manuals on such subjects which can be picked up at a modest price at any bookshop worthy of the name. For now, here are a few basic hints to get you started:

Grammar

Choose a fairly simple and straightforward manual dealing with grammar or ‘English usage’ and read it carefully, but refuse to be intimidated by it. You’ll learn about such matters as whether you should begin a sentence with a conjunction (why ever not?) or end it with a preposition. You’ll discover how to distinguish between ‘fewer’ and ‘less’, and between ‘imply’ and ‘infer’. You’ll find out all about split infinitives (‘to boldly go’) and the use of the subjunctive, and be told that to write a sentence such as ‘He wrote a letter to my husband and I’ or ‘Cycling along the road, the car knocked him over’ (the dreaded ‘hung participle’) constitutes a hanging offence. Not so many years ago, stuff like this was being taught to school children at quite a young age - but times have moved on . . .

What about these and similar rules, then? Follow them if you can, but don’t get at all paranoid about them, and break any rule if the alternative is to write a piece of ugly and convoluted English.

Punctuation

Plenty of tripe and nonsense has been written on this subject, but don’t take it all very seriously. Good punctuation should have one aim above all others - to make it easier for a reader to follow what you’ve written without backtracking or having to puzzle over obscure or ambiguous passages of writing.

Many a teacher would tell you (and maybe one did tell you once upon a time?) that in an ideal world you would make use of a variety of sentences - short ones and longer complex ones. That’s fine if you’re happy with it, but my more down-to-earth recommendation would be that, if in doubt, you should say what you have to say, finish off your sentence with a full-stop, then start a new sentence.

I am a great fan of the semi-colon, however, as you may have noticed in my own writing. Semi-colons are wonderful things -somewhere between a comma and a full-stop, they allow you to hold one statement in abeyance while you add another one to it. Experiment with them if you like; you probably haven’t developed your full potential as a writer unless you’ve played around with the ubiquitous semi-colon.

And . . . (notice the conjunction) you won’t forget to use paragraphs, will you? If a sentence contains one basic idea, expanded or not as the case may be, then a paragraph contains a related set of such ideas. One topic, if you like.

Spelling

Generally you’ve either got this, or you haven’t. I have many very intelligent and highly-educated friends whose spelling is abysmal. Or rather, they habitually misspell twenty or so key words. Use a dictionary by all means - though you do need to know at least something about the spelling of a word in order to find it in a dictionary at all! Try to remember that practise spelt with an’s’ is a verb, while practice spelt with a ‘c’ is a noun. The same is true of the words license and licence, despite what your local pub or Indian restaurant may think! And we all know about ‘i’ before ‘e’, except after ‘c’, don’t we?

If you’re using a word processor, you’ll no doubt activate the spell-checker. This doesn’t solve all problems, of course; some of the terms you’ll use in a family history narrative will be unknown to the checker, and if you use the exact wording of an original document or two, the checker will want to ‘correct’ much of it. Unusual words, including names, which you use very frequently can usually be added to the checker’s existing memory. Some-times, of course, the spell-checker will give you some hilarious and way-off-the-mark alternatives, and if I type ‘twelve pint type’ instead of ‘twelve point type’, there will be no correction made, since ‘pint’ is a perfectly proper word in its own right. A spell-checker can perform some very clever functions, but it can’t read your mind.

Now please bear with me while I offer you a series of further hints on some related topics:

Quotations

You’ll probably want to use quotations of one sort or another fairly frequently in a family history, and can separate then from the main text by using quotation marks or by featuring them in a distinguishing type-face such as italics.

If you’ve tape-recorded your aunt’s reminiscences, why try to re-phrase what she said in your own words? Let her speak for herself! Quote her exact words, indicating those passages you have omitted by the use of three dots in the text. Do have the courtesy, of course, to ask Auntie whether she has any objections to being featured in your family history in this way.

When it comes to including transcriptions of documents written in earlier centuries, the general rule is to quote the original text verbatim - unusual grammar, spelling, punctuation and all. I even transcribe Ye (meaning ‘the’) with a letter ‘Y’, even though I know that the ‘Y’ was just a corruption of an older similar letter-form called a thorn, representing a ‘th’ sound.

Incidentally, you won’t be infringing copyright if you quote a short passage from a printed book, though you should acknowledge the source in a suitably detailed way.

Footnotes or endnotes

If family historians are ever to be taken seriously in the wider world of historical research - and, goodness knows, many do deserve to be! - then they must get in the habit of quoting their sources. You will need to do this with precision. Which documents did you refer to? Are they in your own possession, or are they lodged in a record repository - and if so, which one? What are the relevant ‘call numbers’ or exact references? Present this information in the following form:

‘Settlement Certificate, 10 March 1723/4. Somerset Record Office. SRO DD/LW/18’.

What printed material have you referred to? It may have been a pamphlet, or a book - in which case, give the name of the author, the precise title, the edition (if relevant), the publication date and the relevant page number(s), like this:

‘Stephens, W.B. Sources for English Local History. 3rd Edition, 1994. p.63ff.’

Note in this case that ‘p.63ff.’ means: ‘page 63 and the pages which immediately follow it’, while ‘pp.63, 64’ would mean ‘pages 63 and 64’. If relevant references to a particular topic or person occur throughout a published work, the term ‘passim’ is commonly used.

Use some arcane bibliographical abbreviations when quoting your sources if you like - but it’s not compulsory. I’m speaking here about little gems such as ‘op. cit.’ (from the Latin, opere citato), meaning ‘in the work already quoted’, or ‘ibid’ (from the Latin ibidem), meaning ‘in the same book, chapter, passage, etc’. To get some idea as to how these work, look at the footnotes or end-notes to some scholarly works, or have a close read of Researching and writing history: a practical guide for local historians by David Dymond.

We owe it to our readers to share information with them in this way, if only because, in theory at least, any interested researcher who reads what you have written can then refer back to your original source material if necessary and draw his or her own conclusions from it.

Heaven forbid that we should ever lay ourselves open to the charge levelled by Margaret Stuart, author of Scottish Family History, at those who write what she calls an ‘anecdotal family history’:

This is frequently the work of a lady. It lacks, as a rule, a sufficient number of dates and almost always lacks references. (p. 16)

Phew! Avoid falling into such a category at all costs!

The most usual and effective way of defining your sources is to use footnotes or endnotes:

Footnotes. The very word suggests that these will appear at the foot of each page, which is indeed the case. To create a footnote, place a small number (use ‘superscript’ on a computer) at the end of the sentence in the main text to which it will refer, and place the footnote, preceded by the same number, at the bottom of the relevant page. Footnotes are usually presented in smaller-point type in order to distinguish them from the text itself.

Footnotes might be kind to readers much of the time, but they can be a nightmare for writers to organise, and you’ll sometimes find that they spill over from the bottom of one page to the bottom of the next - a messy procedure.

Not only that, but I can vividly recall the experience of teaching Shakespeare using the splendid Arden edition of his plays, only to find that on some pages there were only three lines or so of Shakespeare, supplemented by a footnote of monumental proportions compiled by the editor!

Endnotes. These work in a similar way, except that you don’t place them at the foot of each page, but group them together at the end of a chapter or towards the back of the book itself.

My own advice, based upon some experience and experimentation, is to use endnotes. If you do so, you can happily add, subtract or re-number such notes at will, without throwing your page-by-page layout into chaos. I’d also recommend that you use a separate endnote numbering sequence for each chapter of your book, running from, say, ‘1’ to ‘16’ in the first chapter and then starting at ‘1’ again for the second. This approach also makes it easier to make changes with minimum disruption. Whether you then decide to place the endnotes relating to chapter one immediately after the chapter itself, or save them all up to the end, is a matter of personal choice. Different authors favour different approaches, just as some decide to present a short bibliography (‘further reading’) after each chapter, and others save everything up for a final listing.

You can use footnotes or endnotes for more than simply quoting your sources, of course. Consider including some or all of the following:

Further family notes. It’s important not to clog up your text with material which might be of interest to readers, but which is ultimately a side-issue that would interrupt the main flow of the narrative. Relegate such extra material to your notes (or to an appendix). Here you can, if you wish, say something about the ancestry of related or distaff lines - that is, those of women who marry into the main family with which you are dealing.

Conjecture. There will be times when you are still uncertain about some key facts or vital relationships. Henry’s birth has not been registered, yet you assume that he is the eldest son of John. Then there seem to be two contemporary Thomases, probably father and son, and a number of references might relate to either man. What do you do? It’s best to decide upon one possibility which you find most convincing, and to stick with this in your main text. Meanwhile, in your notes, say quite honestly that there is a degree of conjecture here, and explain what you are doing: ‘For the purpose of the story, I have assumed that . . . ‘. Don’t keep on apologising for the same uncertainty! The general rule is never to use conjecture on any serious issue without noting the fact. It simply isn’t fair to your readers or to yourself to present hypothesis or conjecture as fact.

The Content of the Story

So much for some of the mechanics of good writing and of quoting your sources. What about the content you will feature using your finely-honed writing skills?

Above all, as you write, do try to get inside the skins of your ancestors - seek that empathy that allows you to share with them what they felt and thought, to experience with them their joys, frustrations, hopes and aspirations. If your research has been thorough and your pedigree is correct, then these people had at least some influence upon your own genetic make-up. Now is your chance to breathe new life back into them, to give their lives, however humble, a further touch of dignity and meaning. Let’s hope that one day your descendants may do as much for you!

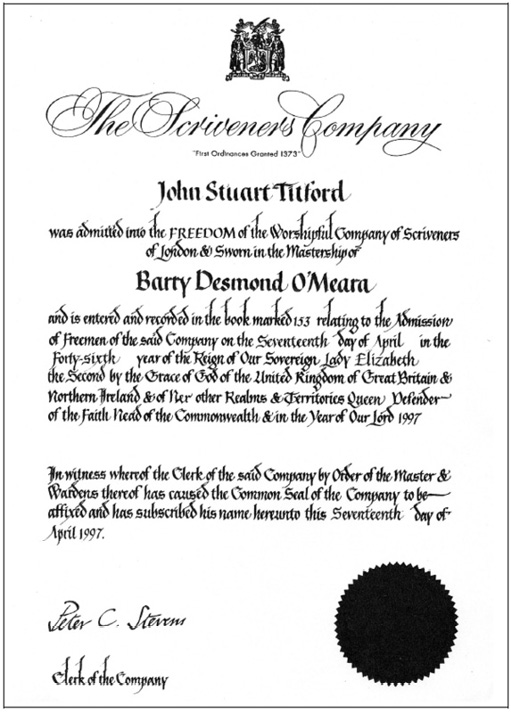

Will you include a brief account of your own life story in your family history book? Why not feature a few relevant documents from your files?

It will be obvious to most family history researchers that the further you go back in time, the less you will know about your ancestors. You may have stumbled across a ‘gateway’ ancestral link that takes you back through nobility to royalty, but that would be the exception rather than the rule. If you spring from humble or middling stock, you will probably know precious little about your 16th or 17th century ancestors - even if you have found out their names!

The trick here is this: the less you know about an ancestor, the more you feature the background when you tell his or her story. After all, the life of a person settled in a small village in centuries past will be inextricably linked with the history of the village itself. Small communities could be claustrophobic places in which everyone knew everyone else - and in which many villagers would be related by blood. So if you tell the story of the village you will in effect be telling the story of your ancestors.

If the foreground grows dim, bring up the background, as it were. Have something to say about the operation of the Elizabethan Poor Laws, about the life of a shoemaker, the tribulations of the English Civil War, the stigma of illegitimacy, the price of food, the weather. This is where the time you may have been able to spend reading books on local or national history will pay great dividends.

For all that, beware of making bold statements such as ‘The 1930s was a decade during which storm clouds were gathering .. unless you can relate such a statement in some meaningful way to the lives of your ancestors. In cases like this, the well-known English genealogist, Michael Gandy, says that we should ask ourselves the question: ‘Were those storm clouds gathering down your grandparents’ street?’ Michael goes even further, offering us a salutary reminder that ‘Our ancestors led their lives slowly, day by day, as we do . . . In real life there isn’t a story. The future isn’t waiting to happen. Most of it is unpredictable, because it’s an accident . . . ‘

I seem to have read a great number of family histories which fall all too easily into the ‘great sweep of history’ trap, and which say something like this:

The early nineteenth century saw a flowering of literary talent as the novels of Jane Austen and the work of the Romantic poets scaled new heights ...

True, true - but what effect might the literary world have had upon your own ancestors? Could they read? Were they sitting at home chatting about Wordsworth and Coleridge, or were they more concerned about the price of bread and the fact that the local pub had been damaged during a thunder storm?

You may have interests of your own, beyond family history as such, which will enable you to bring alive the milieu in which your ancestors lived, giving the reader a real feel for the texture of their everyday lives. You may know something about food in times past, or about music, transport, health or the weather. You may have read a good deal about certain trades or professions; why not reconstruct for the reader a typical day in the life of a blacksmith, a trawlerman, a country doctor or a parson? Costume may fascinate you, and you may be able to say something meaningful about what your ancestors wore, or probably wore. And how did your ancestors speak? Would they have used a strong regional dialect or accent - and if so, of what kind?

Always remember, too, that even when you know what an ancestor did and when he did it, your judgement as to why he acted in the way he did can form part of the story. You may well have to use conjecture - but don’t allow mere guesswork to stand in your text as fact. Suppose, if you like, that your ancestor supported Oliver Cromwell in the 1650s because he was ideologically committed to the parliamentary cause - but don’t state it to be so unless you have real evidence. Maybe your man would always support the winning side, keen to get on with his everyday business?

As you approach the present day, you may well find that you know too much, not too little, about your ancestors and relations. You won’t be able to include everything, and will have to edit. What a good discipline! Not only that, but some of the information you have may well be contradictory. Some people say that great aunt Ada was an adorable, cuddly old lady. Others maintain that she was a real harridan. Which is the truth? Was she one or the other, or a bit of both? It might be foolhardy to attempt a judgement of your own, so why not simply present the alternatives for the reader to think about?

Editing and Revision

You’ll be editing in two different ways as you proceed. To begin with, there’s the family history material which will form the basis of your book, some of which you’ll decide to use and some of which you’ll have to reject, no matter how reluctantly. Don’t include everything you know about your family just because you know it; if you do, you’ll clog up your text and neither you nor the reader will be able to see the wood for the trees. Your accumulated family information is simply a source from which you will write your narrative; you’ll have to be selective. Don’t include material which is unduly tedious, repetitive or only peripheral to the main thrust of the story.

Skeletons

You may want to think very carefully about whether you’ll let skeletons out of their cupboards. You may feel that they should be let out, shaken, dusted down and included - if only because you’re writing a family history, not building a family monument. It won’t always be so simple, alas. You might think that unearthing a bit of scandal - illegitimacy or minor crime - is all part of life’s rich tapestry, but there may be those still alive who had carefully kept the skeleton cupboard door closed and who would be quite genuinely (if unjustifiably?) upset if you were to include material which they regard as embarrassing or even shameful.

You do want to tell the truth, but you don’t want to cause offence. If you can, talk it all through with anyone who might be worried, to see if you can come to some compromise. If not, try to gauge the depth of feeling you’re encountering and act accordingly. Is it worth causing deep offence to a close relation for the sake of writing a book that pulls no punches?

Editing and revising the text

So you’ll need to edit your raw material, deciding what goes in and what stays out. Not only that, but once you’ve started writing you’ll also need to edit or revise your text. If you were a genius beyond measure, you’d simply sit down, write a book from start to finish, stop, and publish. Alas, for us lesser mortals life isn’t quite like that. You really will have to undertake a certain amount of editing and revision of some sort - not root and branch, we hope, but significant for all that.

My own favoured way of proceeding is as follows: I write a certain amount of text - a chapter or a section, possibly - and I leave it for a few days at least, maybe longer. Then I return to it and make revisions as necessary. I’ll correct spelling or punctuation errors, I’ll re-phrase sentences that sound clumsy or where the meaning isn’t clear. I may cut out whole paragraphs or even pages because I don’t think they’re necessary any more, and I may rearrange other blocks of text. You can see why a word processor is so vital if you want to do this job swiftly and efficiently! There was a time when I would have used off-cuts of paper and a pot of glue. Perish the thought!

You really can’t afford to be too precious about everything you’ve written. Even if you sweated blood to complete a page or two of text, you must be brutal at the revision stage if you decide that it isn’t so vital or interesting after all. The more you prune your text, the stronger it will be. To change the metaphor: I always say that it’s easier to cut dead flesh than living flesh. The moment after you’ve finished writing a page or two, nothing would persuade you to abandon it or to edit it severely. Two weeks later you can perhaps take a more detached view. Yes, you thought it was good at the time, it cost you a great deal of energy to write it, it was once precious to you - but now it must be brutally cut. The writer’s waste-paper basket, like the film editor’s cutting room loor, will eventually ill up with all sorts of wonderful material that somehow failed to make it into the final version.

If you don’t mind laying yourself open to constructive criticism, you might be brave enough to ask a friend or relation, or both, to give you an opinion of a sample of your book as it develops. Hand over a section, a cameo or a chapter to people whose judgment you trust, and ask for an honest opinion. Is the information accurate? Has anything been missed out? Does the narrative make sense? Does the style of writing seem appropriate? Don’t just hand a piece of writing to someone and say ‘What do you think of this?’ You’ll get a more useful response if you make it clear that you’d expect some fault to be found, wouldn’t be insulted by any criticism, and would do your best to make changes.

It’s unlikely that there’ll be anything seriously amiss, but do stress that you’d like a frank comment. You might get a response something like: ‘Brilliant... gripping ... fascinating ... but style rather pompous, can’t work out William’s relationship to George, a few words I can’t understand’, and so on. I hope that you’d rather take all this on board sooner rather than later; there may well be minor changes you could make at the outset that could save you a great deal of time, trouble and heartache later on. If you’ve spent months or years completing a mega-book on your family history and never shown any part of it to anyone, it may well be too late to make radical changes. Anyone you do show it to at that advanced stage may be overwhelmed by the bulk of it or may be less inclined to be honest about it because they know it’s your much-loved baby - and you’d certainly be less inclined to re-write a vast amount of text.

You will be writing your book in cameos or sections over a period of time. You might not even compose the chapters in the final order in which they will appear, and your style or your sense of humour may change over weeks and months. At some point you’ll have to weld all the pieces of your book together, creating a holistic product. Having edited each section to your satisfaction, you’ll then have to sit down and read the whole thing through from start to finish. Are there inconsistencies? Have you repeated yourself? Has your writing style changed? Aim for a seamless robe.

Proof-reading

What about proof-reading? The first time I ever wrote a book, I asked a friend who had once worked for a printing firm to proof-read the final manuscript. After all, he’d had experience, hadn’t he? I know now why my friend only agreed to this request rather reluctantly. There is really no magic about proof-reading - it’s just a laborious and time-consuming task.

Proof-read your own work, certainly, but also do everything you can to persuade friends and relations to carry out the same task for you, telling them that they needn’t use any specialist hieroglyphics to indicate corrections, providing the meaning of their annotations is clear.

Different people spot different errors, and there’s a lot to think about. Checking for factual accuracy (including, in particular, dates, addresses, web-site details and the like) is one thing; making sure that the text is clear is another. It really ought to be unambiguous, well-punctuated, free of grammatical howlers and with correct spelling.

Think about layout as well as content, and look out for ‘typos’ -that is, mechanical errors of typing - and double-check your page and footnote/endnote numbering.

If you feel confident enough, try to look for all these features at once - but be warned, it isn’t easy. Your brain prefers to have its tasks separated, not all lumped together. If you’re reading through looking for ‘typos’, don’t for goodness’ sake get too interested in what you’re reading. That’s fatal! You’ll rush ahead to get to the next page, and your eye won’t see, or your brain won’t register, some glaring errors. There is even a rumour around that some professional proof-readers tackle a book from back to front, so that the sense doesn’t get mixed up with the typographical accuracy!

Proof-reading, then, is not the same as simply reading. It requires a detached and objective approach; ideally the text should be read in a staccato way, each word being examined separately. Often it’s the big errors that fail to get noticed, not the small ones. Ask anyone who proof-reads Family Tree Magazine, for example, as I do. If the team of proof-readers misses anything at all, it’ll probably be some huge bold title, set in large-point type, not a small detail in the main text.

If you take your completed work to a commercial printer, he will expect you to read through his own ‘proofs’ before the presses start rolling. There should be few enough errors to spot at that stage - but try not to be lulled into a false sense of security as you carry out this final ‘read’, and do keep any ‘author’s corrections’ to an absolute minimum.

A final thought

Finally, here’s something you’ll just have to learn to live with: no matter how many times you read your text through, no matter how careful you are, no matter how many people do the job, the strong likelihood is that there will still be a few errors in the text on the day you publish. You’ll probably spot these on the very next day - that’s the unfairness of it all.

An Example of Family History Writing

As we are now coming to the end of that part of this book which deals with the writing of a narrative, you might think it unfair of me if I were simply to offer you well-meant advice without giving you a brief example of my own work in this regard - so a short passage from my book The Titford Family 1547-1947 follows. This is not intended to be a classic example of good writing or anything of the kind; rather, I think you might find it interesting to consider the various sources I used in order to compile one single sentence.

Let me sketch the background very simply. In the year 1798 the worthy people of Frome in Somerset established a home-based fighting force called the Frome Selwood Volunteers, formed - in theory, at least - to help repulse an anticipated invasion by Napoleon and his troops. My namesake John Titford, second son of Charles Titford, cheesemonger and pig butcher, joined up as an infantryman. He may have been a brave volunteer, but he was not a healthy man, and on 2 February 1799 he died of consumption at the age of twenty-four and was buried with full military honours. My story continues like this:

It can have been no easy journey for the funeral procession of mourners and military volunteers as they followed the coffin up the steep climb to Catherine Hill Burial Ground that bleak Friday in February with the snow thick on the ground. (p.98)

The question is this: where did the information contained in this sentence come from? Let’s take a few words at a time:

‘No easy journey’

The journey ended at the burial ground and would have started from the family home. Where was that? How do we know? At that time the Titfords lived at the first house on the east side of Pig Street, Frome, near the bridge. Notice that in days when a street worked for its living, its name was an uncompromising Pig Street, not Acacia Avenue or some such pretentious alternative. The detailed Frome rate books for the latter years of the 18th century establish this address for the family, information which is reinforced, as it happens, by a contemporary turnpike deed and by records of the Frome Literary Institute, which was eventually built on the site of the family house.

‘Mourners and military volunteers’

How do we know that this was a military funeral? The family were practising Baptists throughout much of the 18th century, and are significantly absent from the baptismal and burial records of the parish church of St John - a bleak enough scenario for any family historian. However, the burial registers for Badcox Lane Baptist Chapel in the town do exist for this period, and may be consulted at the Public Record Office in London and elsewhere. The Badcox Lane minister, John Kingdon, gave the kind of extra detail in his burial register that may not have appeared had this been recorded by the local Anglican clergyman:

John Titford. Aged 24. With Military Honours.

A list of volunteer infantrymen which appears in a printed history of the Frome Volunteers duly includes the name of ‘John Tizford’ (sic). Not only that, but across the road from the Titford home lay the Frome Bluecoat School, and the son of the master there, Edmund Crocker, kept a diary during this period, which has survived the ravages of time. His diary entry for 2 February reads:

On the 2d instant died in a consumption J Titford aged about 4 or 5 & 20 years. He being a volunteer in our infantry, he was this day interred with the military honours due to him.

‘The steep climb to Catherine Hill Burial Ground’

How do we know that the climb was steep? Easy: visit the town, locate the old site of the burial ground and walk it for yourself!

‘That bleak Friday’

How do we know that 2 February 1799 was a Friday? It’s simply a matter of using a perpetual calendar of some sort; in this case I referred to that excellent publication, Handbook of Dates for Students of English History by C.R. Cheney.

‘With the snow thick on the ground’

How do we know there was snow? Local newspapers contain accounts of the appalling conditions prevailing at this time, with Frome suffering its heaviest fall of snow since 1767, and over in Norfolk, Parson Woodforde, the diarist, was writing that such severe weather had not been known for the last sixty years.

I hope you’ll feel that this has been a useful example of how much information - information that may take weeks or months to unearth - can be compressed into just a few words. This is what I meant when I referred earlier to the act of synthesising your family history data into a narrative which is based upon fact but which will hopefully help the reader create a scene in his or her own mind. I’ve tried here to bring the past alive - or to bring it alive again, if you prefer.

I sometimes think that writing fiction would be easy; much of the time you’d be in control of the facts. Writing history or family history is different: the facts must be in control of you.