Design is one of the basic characteristics of what it means to be human, and an essential determinant of the quality of human life. (John Heskett, Toothpicks and logos, 2002, p 5)

On 26 May 2011 the international news magazine The Economist featured the cover headline ‘Welcome to the Anthropocene’, depicting an artificially created Earth. The issue noted that, according to geologists, humankind is entering a new era where the majority of our planet’s geological, ecological and atmospheric processes are affected by humans. Our civilization’s entry into the Anthropocene, literally meaning ‘The Age of Man’, underlines how our species is increasingly shaping our environments not only locally but also at a global scale to meet our needs. This shift is characterised by some as ‘the human turn’, a world in which ‘man has increasingly moved to the centre as a creature that has set itself above and beyond, and even reshaped, its natural surroundings’ (Raffnsøe, 2013, p 5). This fact has wide-reaching implications for many of our natural scientific disciplines and for our understanding of our role on the planet.

The human turn can be construed from a range of angles – geological, philosophical, social and industrial. The coming of the Anthropocene might also be seen as the culmination of the last several hundred years’ design of the increasingly human-made environments in which we live: ‘The capacity to shape our world has now reached such a pitch that few aspects of the planet are left in pristine condition, and, on a detailed level, life is entirely conditioned by designed outcomes of one kind or another’ (Heskett, 2002, p 8). The notion that our planet can be transformed by design is by no means new. In fact, the universality of design is a key strand in much thinking and writing on design. Buckminster Fuller, the futurist, architect and designer suggested already in the early 1970s, in Victor Papaneks’ Design for the real world, that ‘Design is everything’. C. West Churchman, in 1971, asserted that ‘We believe we can change our environment in ways that will better serve our purposes’ (1971, p 3). Norman Potter opens his influential book, What is a Designer?, with the statement that ‘Every human being is a designer’ (Potter, 2002).

Behind much of the contemporary understanding of design is a notion of design as a problem-solving activity. Famously, when asked about the boundaries of design, the renowned furniture designer Charles Eames answered ‘What are the boundaries of problems?’ (Moggridge, 2007, p 648). Design thus cuts across all other human activities as a particular concept that addresses how physical, commercial, social and public outcomes are created. Much of this design activity is not explicit, or intentional. As the digital, social and physical tools for designing are becoming democratised, ‘everybody designs’. Professor Ezio Manzini at Milan Polytechnic, a leading design school, distinguishes between ‘diffuse design’, by non-experts or ordinary people, and ‘expert design’, by professionally trained designers (Manzini, 2015, p 37).

While it can be debated whether design is ‘everything’, it seems without doubt that ‘life in contemporary society is saturated by design’ (Simonsen et al, 2014, p 1). However, as design has reached this saturation point, not least through the proliferation of physical objects and expressions, it has begun to undergo significant change. Forms and objects of design move towards services and systems, design practice is changing with notions of strengthened end-user and stakeholder involvement, and with new ideas about the contributions of design to the theory and practice of management. At a deeper level, the context for design is changing. Design as a discipline is being redefined by technological and social megatrends that have significance for how organisations are run, how products and services are shaped and how value is created. As part of this shift in context, design is finding its way into the public sector.

This chapter provides an overview of the context, history, development and definition of design towards ‘new’ forms and meanings of design, and the emergent application of design in the public sector. It aims to unwrap the various definitions and directions and to distil some characteristics or sensibilities of design approaches. It develops the idea of design management and the notion of public managers as designers – a key theme in this book. Finally I discuss the notion and role of design as a particular ‘attitude’.

The rise of design as a distinct profession in contemporary society was historically linked to industrialisation and the rise of mass production, which in turn was driven by developments in technology and in the organisation of work (Sparke, 2004; Manzini, 2015). In this perspective, design is a key factor linking consumption and new technological opportunities. As designers found ways to create marketable products that fulfilled people’s tastes and demands, these in turn influenced modern society’s culture of consumption.

Just plainly observing everyday life in our current society, it seems clear that objects of consumption, ranging from the clothes we wear to the mobile phones we carry and to our preferred forms of transportation, are powerful signifiers of our identity. In other words, there has historically been a ‘close-coupled, recursive relation between the design profession and the structure of capitalist society’ (Shove et al, 2007, p 120). Not only that, but designed products influence how we behave in our daily lives. As is recognised in fields as diverse as sociology, anthropology, behavioural science and technology, material objects make particular social and practical arrangements possible in our lives and in society. According to Shove et al (2007), this means that design is located as a medium through which social and commercial ambitions are materialised and realised. Friedman and Stolterman (2014, p viii) say that design ‘is always more than a general, abstract way of working. Design takes concrete form in the work of the service professions that meet human needs, a broad range of making and planning disciplines.’

Even as we note that much of our current world is essentially designed and shaped by humans, and as the context for design has shifted markedly over time, there is no clear picture of what exactly characterises design activity.1 Richard Buchanan proposes that design can be thought of as a liberal art of technological culture. In this definition, design is viewed as an integrative, supple discipline, ‘amenable to radically different interpretations in philosophy as well as in practice’ (1990, p 18). As Buchanan suggests, the history of design, as well as contemporary developments in design, shows that design has not one, but many shapes. Part of this challenge, but perhaps also the richness of the term, is that design can be treated ‘ambiguously both as a process and as a result of that process’ (Sparke, 2004, p 3). According to others, design holds substantially more than these two dimensions, so that ‘“design” has so many levels of meaning that it is itself a source of confusion’ (Heskett, 2002, p 5).

Heskett points out that since design has never grown to be a unified profession like law, engineering or medicine, the field has ‘splintered into ever-greater subdivisions of practice’ (Heskett, 2002, p 7). In spite of this splintering, some overall patterns in the meaning of design may none the less be identified. These patterns are very closely related to the history of design and its relations to industrial society laid out in the preceding section.

For the purpose of understanding what it is to design, in the context of this book I suggest that design can be viewed as (1) a plan for achieving a particular change; (2) a practice with a particular set of approaches, methods, tools and processes for creating such plans; (3) a certain way of reasoning underlying or guiding these processes. Each of these understandings of design has been, and still is, undergoing significant development, and I address each of those emergent patterns, or ‘layerings’ to use another term suggested by Heskett, relating to planning, practices and reasoning, respectively. The definitions pave the way for considering design more explicitly as a particular approach to management and to leading organisational change, which I consider in more detail in the final section in this chapter.

The late Bill Moggridge, a co-founder of the design firm IDEO and director of the Cooper-Hewitt design museum in New York, suggests that we look to the famous design couple Charles and Ray Eames for a useful definition of design. According to Charles Eames, design can be defined as ‘A plan for arranging elements in such a way as to best accomplish a particular purpose’ (quoted in Moggridge, 2007, p 648). Eames hereby highlights the emphasis in design of arrangement, construction of various parts as well as purposefulness: design is concerned with achieving a particular intent. Roughly in line with this definition, Herbert Simon proposed in the late 1960s in his work The sciences of the artificial that ‘everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones’ (Simon, 1996, p 111). In Simon’s definition the plan has to do with establishing possible actions, again with the intent to change the current order. Whether that intent is for a commercial or a social purpose is left open.

The question of what the design plan is for, or what the nature of the intended change is supposed to be, has developed significantly over time in terms of variation and refinement. The objective of design has moved far beyond the creation of physical products or graphics, towards services and systems. ‘Historically, design changed “things”. More recently it’s changed services and interactions. Looking ahead it will change companies, industries and countries. Perhaps it will eventually change the climate and our genetic code,’ claims a book on the new features of design (Giudice and Ireland, 2014). However, the notion that design addresses a broader set of objectives is by no means new. Donald Schön, in his 1983 seminal work, The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action, quips that ‘Increasingly there has been a tendency to think of policies, institutions, and behaviour itself, as objects of design’ (1983, p 77). While he was sceptical of the risk of blurring the differences and specific properties across professions spanning from architecture and media to policy making, Schön acknowledged that ‘we may discover, at a deeper level, a generic design process which underlies these differences’ (1983, p 77).

According to Richard Buchanan, design affects contemporary life in at least four areas: symbolic and visual design (communication), the design of material objects (construction), design of activities and organised services (strategic planning) and the design of complex systems or environments for living, working, playing and learning (systemic integration) (Buchanan, 1990). Elizabeth Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers (2008) similarly argue that design as a discipline is undergoing a significant transformation, which incidentally places it more squarely at the heart of an organisation’s ability to create new valuable solutions.

Design is also increasingly embracing ‘the social’. Ezio Manzini (2011, p 1) emphasises that design in the 21st century has followed the evolution of economic thinking in reflecting ‘the loss of the illusion of control, or the discovery of complexity’ [original emphasis]. This has contributed to a wider change in design culture that has arguably been under way since the late 1960s and that could be characterised as ‘design for social good’. Although he has been criticised for an overly rational and perhaps reductionist interpretation of design as a ‘science of the artificial’, Herbert Simon himself addressed design for social planning. He proposed that there are wider implications of design activity, which requires careful consideration of issues such as problem representation, data, client relationships, the designer’s time and attention, and ambiguity of goals and objectives (Simon, 1996, p 141).

The intersection of the recognition of social complexity, which might be understood as the characteristic of highly interconnected systems (Colander and Kupers, 2014) on the one hand, and the ambition to design for positive social change on the other, has led to multiple new strands of design. This is in part captured by the movement of social entrepreneurship and social innovation (Mulgan et al, 2006; Murray et al, 2009; Ellis, 2010; Manzini, 2015), and in part by the growing interest in public sector innovation (Mulgan and Albury, 2003; Eggers and O’Leary, 2009; Bason, 2010; Boyer et al, 2011; Manzini and Staszowski, 2013; Bason, 2014a). One of the foremost observers and documenters of the transformation of the design discipline, Liz Sanders, suggests that today, ‘Design can bring the foundational skills of visualization, problem solving and creativity to a collective level and seed the emergence of transdisciplinary approaches to addressing the complex issues critical to society today’ (2014, p 133).

Shifting to understanding design as practice, or capacity, numerous definitions come to the surface. John Heskett proposes that design is best defined as ‘the human capacity to shape and make our environments in ways unprecedented in nature, to serve our needs and give meaning to our lives’ (2002, p 7). Others contend that design practice can be considered as the discipline of melding the sensibility and methods of a designer with what is technologically feasible to meet people’s real-world needs (Norman, 1988; Sanders and Stappers, 2008; Brown, 2009; Halse et al, 2010; Michlewski, 2015). This definition highlights tools and concrete practices connected to running specific design projects and shaping new products or services. One might characterise this as much as a capability (Heskett, 2002; Jenkins, 2008; Cooper et al, 2011).

As with recent developments in design as plan, design practice has developed tremendously in the past few decades. Meyer (2014) pragmatically notes that design must be understood as a set of activities: ‘methods, approaches and techniques that provide its practitioners with a way of working together in a highly productive way’ (2014, p 188). The perhaps most fundamental shift has been that of questioning the role of the gifted, single ‘heroic’ designer as the key agent in design practice, and viewing design practice much more as a social, collaborative process. This certainly does not mean that the iconic, gifted designer is no longer a key figure in our Western commercial culture; one might even argue that superstar designers have never been more celebrated. Further, it does not mean that there is no difference between highly professional expert designers, on the one hand, and ‘everday designers’, on the other (Boland and Collopy, 2004; Verganti, 2009; Manzini, 2015)

However, across business and government significant strands of design practice are simultaneously shifting to ‘co’: To col-laboration, co-creation and co-design as central features, emphasising the explicit and systematic involvement of users, clients, partners, suppliers and other stakeholders in the design process and, in essence, challenging the role of the single designer (von Hippel, 2005; Shove et al, 2007; Michlewski, 2008, 2015; Sanders and Stappers, 2008; Bason, 2010; Halse et al, 2010; Meroni and Sangiorgi, 2011; Ansell and Torfing, 2014). Variations such as participatory design and service design, which focus on (re)designing service processes, are rapidly growing (Bate and Robert, 2007; Shove et al, 2007; Brown, 2009; Cooper and Junginger, 2011; Polaine et al, 2013; Manzini, 2015). In particular, the new shapes of design ‘for’ a variety of purposes are usually associated with such a social or collaborative approach where outcomes are co-created or co-designed together with a variety of actors, often taking the perspectives of end-users such as consumers or citizens as their point of departure. In fact, design is increasingly explicitly characterised as ‘human centred’ (Brown, 2009; European Commission, 2012). This in turn has brought more research-oriented activities to design practice, including methods drawing on anthropology and ethnography. Halse et al (2010, p 27) suggest three major strategies that embody the notion of a design-anthropological approach.

• Exploratory inquiry: researching without a prior hypothesis to be tested but, rather, aiming at understanding purpose and intent: why, for whom, and for what is a certain understanding directed?

• Sustained participation: ‘No design team will possess all the relevant knowledge by itself’, claim Halse et al (2010), and they suggest that clients and stakeholders must be engaged in a continuous dialogue.

• Generative prototyping: taking problems and solutions as the basic elements of continuous loops of iterations. By experimenting and trying out different thoughts and actions, generative prototypes evaluate not only whether a solution will work, but also whether the understanding is right and allows new meanings to evolve within the network of stakeholders.

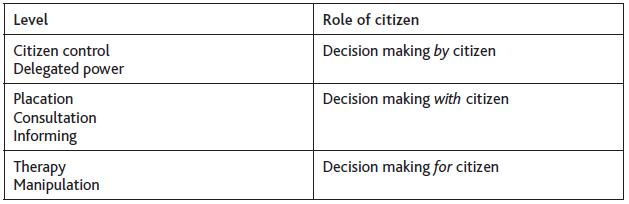

So the tools applied for collaborative design include, for instance, methods for creative problem solving, user research and involvement, visualisation, concept development, rapid prototyping, test and experimentation, all of which help designers to ‘rehearse the future’ (Halse et al, 2010). In the context of the emerging field of design it also seems clear that the role of the (specialist) designer is shifting towards one as process facilitator or coach (Shove et al, 2007; Sanders and Stappers, 2008; Meyer, 2011). The change here cannot be over-estimated: the traditional role of the designer was to work with a client, either as an external consultant or in a design function within a firm, to provide design ‘input’ based on a brief or problem specification. In the collaborative mode of design, the role of the designer – while still drawing on his or her professional practices, attitudes and ways of reasoning – is essentially to involve actors from end-users to managers to staff in a process of discovery and co-creation. Table 3.1, first suggested by Sherry Arnstein (1969) and later developed by Sabine Junginger, seeks to illustrate the span of roles of citizens’ engagement with public authorities on a ‘ladder’ from highly subordinate to highly empowered.2

Table 3.1: Ladder of citizen involvement in decision making

The table illustrates that citizens can be cast into widely different roles, depending on the way in which government bodies choose to engage with them. Creating the right conditions for enabling these citizen roles can be viewed as a design task.

This set of definitions include design as a mind-set (Sanders, 2014), a way of thinking (Buchanan, 1990; Brown, 2009; Martin 2009) or an attitude (Boland and Collopy, 2004; Michlewski 2008, 2015). Arguably, design thinking is the strand, or interpretation, of design which since the early 2000s has become almost a household term in business circles (Brown, 2009; Martin 2009). Roger Martin (2009) characterises design thinking as the ability to manage and move between the opposing processes of analysis, involving rigour and ‘algorithmic’ exploitation, on the one hand, and synthesis, involving interpretation and exploration of ‘mysteries’, on the other hand. At the heart of design thinking is thus, according to Martin, the balancing or bridging of two different cognitive styles: the analytical-logical mind-set that characterises many large organisations and professional bureaucracies, and the more interpretative, intuitive mind-set that characterises the arts and creative professions. Martin highlights the capacity for abductive reasoning – which he describes as the ability to detect and follow a ‘hunch’ about a possible solution, bridging the gap between analysis and synthesis (Martin, 2007; 2009).

As Piore and Lester (2006), as well as Verganti (2009), have argued, intuition and the ability to interpret information to form new solutions is the ‘missing dimension’ of innovation. Tim Brown also acknowledges explicitly, referring to Martin’s The Opposable Mind (Martin, 2007), that ‘design thinking is neither art nor science nor religion. It is the capacity, ultimately, for integrative thinking’ (Brown, 2009). Perhaps the integrative nature of design has best been characterised by Dick Buchanan, who states that design thinking is about moving toward ‘new integrations of signs, things, actions and environments that address the concrete needs and values of human beings in diverse circumstances’ (1990, p 20). This directs our attention to understanding design as an approach to management, placing it ‘at the core of effective strategy development, organizational change, and constraint-sensitive problem solving’ (Boland and Collopy, 2004, p 17).

However, the term design thinking has also attracted wide criticism. One of its earliest and most vocal proponents, Bruce Nussbaum, distanced himself from the term in a widely read op-ed titled ‘Design Thinking is a Failed Experiment. So What’s Next?’ (Nussbaum, 2011). Interestingly, his piece coincided with his launch of a new book titled Creativity Quotient, which argues that organisations need to foster creativity rather than embrace design.

More serious critique has been launched from design circles that argue that exactly the term ‘thinking’ misses the point, since design is as much a practice, even a craft, as it is a particular way of thinking. From this point of view design thinking is considered somewhat shallow. However, there is probably no doubt that the label ‘thinking’ has been instrumental in propelling design, as a discipline, into the awareness of managers, public as well as private. Design thinking, as a term and as it has been portrayed in a wide range of articles and books, has helped to popularise design far beyond the profession and related practices. Michlewski (2015, p 144) has sought to create some order in the various design ‘frames’ by suggesting that design thinking mainly places itself squarely between the practical concerns of design professionals, on the one hand, and the epistemic concerns of design researchers and philosophers, on the other. He characterises design thinking as ‘a movement that promotes the philosophies, methods and tools that originate in the practice and culture of the design professions’ (2015, p xviii).

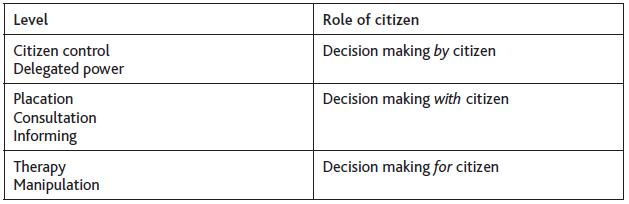

In summary, this section has discussed three perspectives, which help define design. As shown in the table below, I have characterised each perspective and how it is undergoing change.

Table 3.2: Changing definitions of design

Increasingly, design is thus viewed as more than approaches and tools. It is also a discipline that has inspired non-designers to borrow some of its approaches and tools into the sphere of management. In the following I will consider two dimensions of this discussion. First, the management of design, and second, designing as managing, or as a particular attitude to managing that challenges our understanding of managers as decision makers.

One of the insights I have found to resonate most powerfully with public managers (and, indeed, many leaders in business as well) is the following characterisation by Case Western professors Richard Boland and Fred Collopy:

Managers, as designers, are thrown into situations that are not of their own making yet for which they are responsible to produce a desired outcome. They operate in a problem space with no firm basis for judging one solution as superior to another, and still they must proceed. (Boland and Collopy, 2004, p 17)

With the term ‘thrownness’, Boland and Collopy refer to the scholar of sense making in organisations, Karl Weick, who argues that any design activity must necessarily take place in an environment already ripe with ‘designed’ activities (Weick, 2004). Hereby the role of design becomes one of re-design, not of designing on a blank slate. The job of management, as designing, becomes one of balancing on-going decision making with efforts to design (new) practices. Boland and Collopy’s edited volume further explores what a design vocabulary, a design ‘attitude’ and design practice might bring to the management profession.

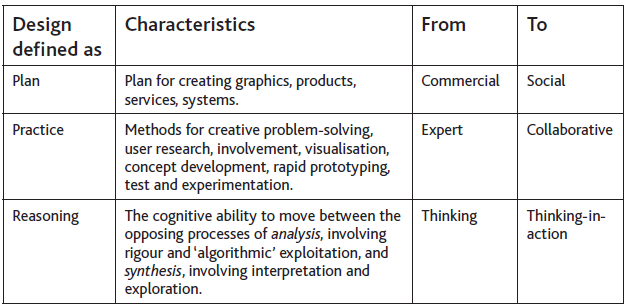

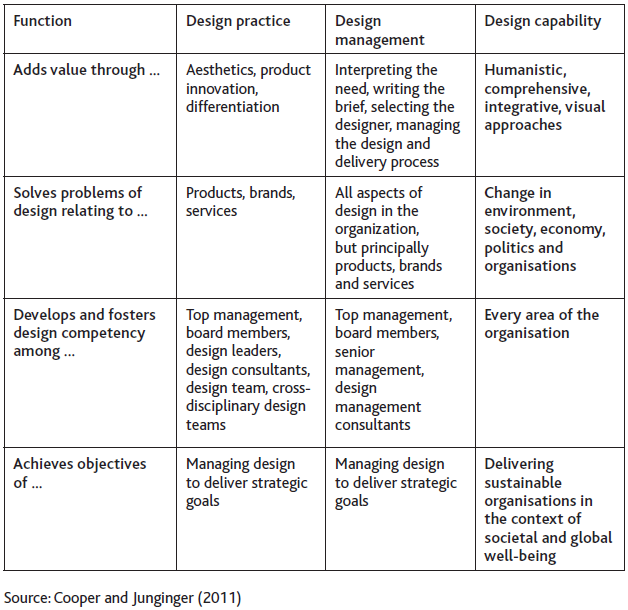

Cooper and Junginger (2011, p 1) state that the intersection of design and management has generated decades of ‘lively debate’ in the design and business communities. What are the relationships between design and management, and between management of design and design management? As new and more collaborative approaches to innovation in the public sector are coming to the fore, this question is increasingly relevant to public managers. As service design, interaction design, human-centred design and strategic design approaches – in their various shapes and forms – are being applied to public problems, it becomes increasingly important to reflect on how managers relate to these strategies (Table 3.2).

Cooper and Junginger argue that the third paradigm – design capability – is particularly salient in public sector setting, as a reflection of the social and human nature of most, if not all, public policy concerns. A global environment characterised by intractable social, economic, environmental and political challenges calls for an increased use of design-led approaches to problem solving: ‘Because the skills and methods that constitute design are useful in responding to the challenges facing us today, designing is now being recognized as a general human capability. As such, it can be harnessed by organizations and apply to a wide range of organizational problems’ (Cooper and Junginger, 2011, p 27).

Table 3.3: Paradigms of design management

Of concern to this book is how public managers themselves engage with ‘design’ in their quest to proactively use their organisations to effect human and societal progress. The question then becomes not only how design approaches are in practice applied in public sector organisations to tackle public problems, but also the evolution of design capability: how public managers themselves ‘design’ in their quest to proactively affect human and societal progress (Boland and Collopy, 2004).

We have seen that design can be viewed as a particular way of reasoning; however, in considering ‘design attitude’ there is more to this perspective on design.

Richard Boland has argued that ‘The way we narrate the story of our experience to ourselves and others as we engage in a series of events gives meaning to the problem space we construct and the calculations we make within it’ (Boland and Collopy, 2004, p 107). In this book I will therefore examine how particular public managers tell their stories of innovation and change, which happens to be in contexts where design approaches have been utilised. How do they, as managers and leaders, think and act as part of that process? How do they ‘design’?

The notion of ‘managers designing’ implies that they go about innovation activities in line with what Boland and Collopy (2004) have called a ‘design attitude’, In a somewhat similar vein, Tom Peters (1997) writes of ‘design mindfulness’ as a way to approach problems, questioning what the manager can do to make solutions work better for the organisation and/or those around it. Meyer (2011, p 197) points out that in change projects building on internal expertise, ‘every organization has a few of these individuals who may not instinctively self-identify as designers or design thinkers but who display an immediately recognizable set of behaviours that tag them as design minded’. Similarly, the public managers I have interview for the present research do not generally think of themselves as designers, but they do seem to display attitudes or behaviours that are ‘design minded’.

Boland and Collopy define design attitude as the ‘expectations and orientations one brings to a design project’ (Boland and Collopy, 2004, p 9). They make the point that ‘a design attitude views each project as an opportunity for invention that includes a questioning of basic assumptions and a resolve to leave the world a better place than we found it’ (Boland and Collopy, 2004, p 9). They hereby frame design attitude in opposition to a decision attitude, which portrays the manager as facing a fixed set of alternative courses of action from which a choice must be made. A decision attitude is suited for clearly defined and stable situations and when the feasible alternatives are well known. The highly influential Herbert Simon’s scholarship across nearly half a century was to establish the role of management as that of representing problems and making decisions between a set of alternatives.

However, many of the problem sets facing managers – including public managers – in the current environment have vastly different, less stable and more complex characteristics, which may call for an increased focus on design attitude. By complex characteristics I refer to systems with large numbers of interacting elements; where interactions are non-linear so that minor changes can have disproportionately large consequences; which are dynamic and emergent; and where hindsight cannot lead to foresight because external conditions constantly change (Snowden and Boone, 2007; Bourgon, 2012). Not all public problems are like this, but many are. We could therefore ask whether the concept of design attitude can help us to understand the role of the public manager as someone who catalyses innovation, often in complex settings, by taking responsibility, in different ways, for designing organisational responses to the challenges and opportunities they face.

Such a break from the mainstream understanding of ‘managing as making decisions’ towards ‘managing as designing’ is significant, and essentially underlies the entire emerging paradigm of design as a discipline of management. In a nutshell, design methods offer the potential to reframe the role of management from ‘decision making’ (choosing from alternatives) to ‘future making’ (creating the alternatives from which to choose). The key question becomes whether managers possess, or can come to possess, the skills, tools and processes that allow them to address problems in designerly ways.

In a systematic exploration of what Boland and Collopy’s notion of design attitude might entail, Kamil Michlewski (2008) undertook doctoral research in which he interviewed a number of design consultants and managers from firms like IDEO and Philips Design and mapped how these people viewed their roles and practices. On the basis of this study he subsequently proposed five characteristic dimensions of design attitude. More recently, he has developed his thesis into a book (Michlewski, 2015) and has tested a number of the design attitude dimensions statistically through a questionnaire-based survey among 235 designers and non-designers (174 classified themselves as designers). According to Michlewski (2015), the survey showed a statistically significant difference in the attitudinal dimensions between designers and non-designers.

These attitudinal dimensions are a useful conceptual frame for understanding public managers’ approaches to problem solving and the generation of new ideas, innovations and governance models by engaging with design. The design attitudes as presented in Michlewski’s most recent and developed (2015) work are as follows:4

• Embracing uncertainty and ambiguity. Michlewski perceives this dimension in terms of the willingness to engage in a process that is not pre-determined or planned ahead, and where outcomes are unknown or uncertain. It is an approach to change that is open to risk and the loss of control. According to Michlewski, really creative processes are ‘wonky’ and often stop-start. The challenge for managers is to not resist, but to allow for the creative process to unfold.5 One might say that this reflects an acceptance of Boland and Collopy’s (2004) point that managers operate in a problem space where the basis for judging one solution as superior to another is at best questionable. Managers who embrace uncertainty and ambiguity are likely to say ‘why don’t we just do it and see where it leads us?’

• Engaging deep empathy. Michlewski finds that designers intuitively ‘tune in’ to people’s needs and how they as users relate to signs, things, services and systems. What do people want, what kind of quality of life are they seeking? Using true empathy requires courage and honesty in abandoning one’s mental models. Engaging personal and commercial empathy is, in Michlewski’s interpretation, also about listening to better understand the human, emotional aspect of experiencing products and services.

• Embracing the power of the five senses. According to Michlewski, designers have a ‘fondness’ for using their aesthetic sense and judgement while interacting with the environment. As a third dimension of design attitude, this is not only about ‘making things visible’, or about crafting beautiful designs, but about merging form and function in ways that work well for people, drawing on all five human senses. Michlewski (2015, p 84) characterises it as the ability to ‘appreciate and use the feedback provided by multiple senses to assess the efficacy of the solutions they are developing’. Designers recognise the significance of a range if sensory stimuli and are more likely than other professionals engage consciously with multiple senses in their work.

• Playfully bringing to life. To Michlewski this attitude concerns the ability to create ‘traction’ and direction in an innovative process or dialogue. In his research Michlewski finds that designers believe in the power of humour, playfulness and bringing ideas to life. At the heart of design practice, he finds, is an attitude that embraces unexpected experimentation and exploration. This dimension is closely related to designers’ affinity for creating things, for creatively bringing new ideas to fruition. One designer in Michlewski’s research describes this as the process of visualisation and rapid prototyping – a core activity of many, if not all, designers. From a management perspective one could view this as the desire to effect change and create value; to see that new ideas about strategy or organisation are realised.

• Creating new meaning from complexity. Michlewski argues that what is at the heart of designers’ ways of doing things is the ability to reconcile multiple, often contradicting points of view into something valuable that works – they use empathy as the gauge. This describes the designer as a person who ‘consolidates various meanings and “reconciles” contradicting objectives’ (Michlewski 2008, p 5). This reflects an ability to view a situation from a wide variety of perspectives, essentially creating a landscape for exploring further problems. Michlewski defines this process, essentially of consolidating multidimensional meanings, as the manager’s ability to operate in an analytical-synthetical loop in order to achieve a balance between the cohesion of the organisation, on the one hand, and external constraints, on the other.

These five dimensions were empirically derived through ethnographic research within the design consultancy community; a significant number of the interviewees were themselves trained designers. Most public managers have a professional and experiential background that is vastly different; and their personal characteristics and attitudes are, one should think, unlikely to be similar to those of designers. However, design attitude is an interesting interpretative prism. Some of the more intriguing questions might be: Are managers who choose to engage with design practice (for instance by hiring service designers to develop a particular service or policy) somehow inclined to display something akin to the attitude of professional designers? And further, does the concrete unfolding of a design project catalyse more of a design attitude on the part of the manager, essentially enabling the emergence of some degree of stronger design sensibility, or confidence?

Through the sections above I have shown how design is a profession undergoing change and that is now lending itself to a very broad range of applications, increasingly also in the public and social sector. Design is becoming not only more socially oriented but also more collaborative, open and engaging. For the purpose of this book, I suggest the following definition of design as an approach or process:

Design is a systematic, creative process that combines different elements to achieve a particular commercial or societal purpose. The process is visual and experimental, with human experience and behaviour at its core. The results can be graphics, products, services, systems and new organisation and governance models.

This definition can be useful to keep in mind as I unfold how public managers have used design in practice, in Part Two of the book.

This chapter has explored what design is and what it could mean in a management and policy context, and how the discipline is undergoing significant transformations. I have discussed the emerging, if perhaps still somewhat marginal, practices of co-design, service design and related approaches as a distinct branch of the design profession. Further, I have relayed the relatively novel phenomenon – rising over the last decade or so – of applying design to public services. Finally, I have considered the tentative discussions and perspectives on the relationship between management and design, or managers and designers, which still seem to be relatively unexplored. A key point here is how the use of design signifies a fundamentally different approach to leading change.

As a public manager who is curious to engage with design, your starting point could be:

• Understanding the value designers and design approaches can bring to your organisation, beyond graphic design and visual communication, but as a strategic and socially oriented and collaborative approach to innovation.

• Recognising that much design work in the public sector is not about novelty or invention, but about re-design of current solutions and systems. This entails dealing with the ‘thrownness’ of everyday life as a manager, carving out the time and opportunity to ask what the need for change really is.

• Reflecting on what a design attitude to management might mean for your own leadership practice. Not least, what would it mean if new projects were really addressed more often as opportunities for re-invention and re-design?

• Being willing to invest in design, either by commissioning outside consultancy services or by recruiting designers into development and innovation roles in public sector organisations, perhaps organised in innovation teams or labs.

The following chapter charts the emergence of a new paradigm of public management and analyses the surprisingly similar kinds of changes that are taking place within that profession.

1 The following sections build on Bason (2014b).

2 First relayed by Sabine Junginger at a paper presentation at the DMI research conference in London, September 2014.

3 This section builds on Bason (2014a).

4 The original (Michlewski, 2008) terminology on design attitudes was a little less straightforward, which perhaps reflects that Michlewski’s recent work (2015) is intended for a wider and also non-academic audience: (1) embracing discontinuity and open-endedness; (2) engaging polysensorial aesthetics; (3) engaging personal and commercial empathy; (4) creating, bringing to life; (5) consolidating multi-dimensional meanings.

5 Based on e-mail correspondence with author (February–March 2014) and subsequent cross-referencing with his new book (Michlewski, 2015).