It is both misguided and remarkably premature to announce the death of the ethos of bureaucratic office. (Paul du Gay, In Praise of Bureaucracy, 2000, p 146)

Often, when I have been involved in conversations on the future of government, the term ‘bureaucracy’ has been invoked as the ultimate threat to innovation and change in public organisations. However, the daily reality of almost every manager and employee in the public sector is that bureaucratic management is a fundamental part of how they work. As new forms of innovative ways of working are introduced, they must thus come somehow to co-exist with the existing paradigm. In one public organisation that I have worked with, the staff chose to embrace the interplay between bureaucracy and innovation by coining the term ‘innocracy’. They recognised that in their work (taxation services), there might be a need for fresh thinking and innovation, but some of the core bureaucratic ground rules were probably sound enough.

Certainly, the presence of bureaucratic governance cannot be ignored. Peters (2010, p 147) suggests that ‘Despite numerous changes in the public sector, Max Weber’s conceptions of bureaucracy still constitute the starting point for most discussions’; and so will they for discussion in this book. My sense is that without an honest recognition of our bureaucratic legacy and its strengths and weaknesses, much work to bring design into play in public organisations will remain unrealistic, out of touch with reality and naïve.

I thus start this chapter by providing a classic typology of three eras of public management: traditional public administration, new public management and networked governance. I characterise the two first approaches before expanding on the nature and properties associated with networked governance. I consider whether – as some now claim – public management theory and practice might be undergoing transformations that (roughly) follow a trajectory that mirrors the evolution of the design profession. What are the principles and patterns within the chorus of voices arguing for new approaches to public management?

I conclude the chapter by examining an intriguing question: Is some degree of convergence taking place between design and public management? To what extent are recent developments in the two fields somewhat similar? What does that tell us about the potential of design approaches to catalyse the next public governance model?

In a recent analysis of the future of the state Yves Doz, a strategy professor, and Mikko Koskonen, a Finnish senior government official, point out that the complexity of the policy environment has developed dramatically at the same time (especially since the 2008 global financial crisis) that the availability of resources has declined. Government organisations find themselves under conditions of technological, environmental, social and political turbulence at the same time as their access to funding and resources is constrained. Part of the austerity has perhaps to some extent been self-imposed, but none the less, the current situation seems to present three major challenges that put the current model of public governance under strain (Doz and Koskonen, 2014, pp 6–8): strategic atrophy, the imprisonment of resources, and diverging commitments. Doz and Koskonen argue that ‘many policies need to incorporate a far wider array of contingencies and interrelated factors in their search for solutions – decision-makers need to dig deeper in their search for solutions, seek input from farther afield, and execute as a “single, unified government” rather than from their traditional bureaucratic silos’ (2014, p 6). As Ansell and Torfing (2014) argue, this kind of collaborative approach to public sector innovation calls not for less management, but for a different kind of management and governance.

Not least, the siloed nature of organisations and knowledge domains is a key legacy of public institutions. Professional disciplines such as economics, law and health work in distinct organisational and professional domains have a tendency to impede communication, thus creating a culture of hyper-specialisation. Each discipline or agency looks at the world through its perceptual lens and operates within the rules of the silo, creating biases. This is particularly problematic, given that the types of scaled challenges discussed above are interlaced, with interdependencies that do not respect disciplinary silos. The central planning culture and political aversion to real experimentation work against modalities of innovation that are focused on fundamentally rethinking solutions and systems (Doz and Koskonen, 2014; Banerjee, 2014).

The need for better alignment between public organisations, their objectives and their changing context has certainly not gone unnoticed among public management practitioners and scholars. So, what are the discussions within public management, how is the existing legacy being challenged and to what extent might the changes occurring even be somehow aligned with the innovations taking place within the design profession?

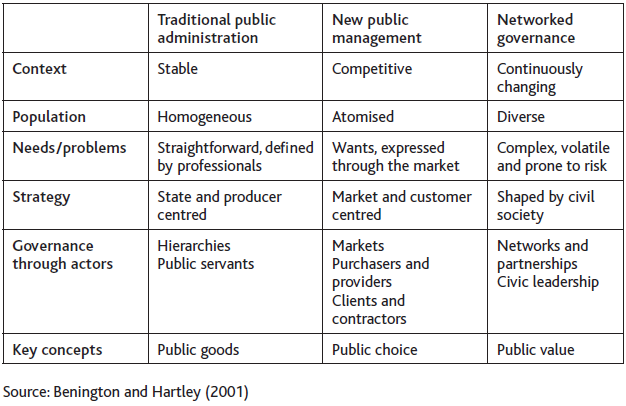

The search is on among public management practitioners, scholars and consultants for a new form of public governance. That search is best understood in the frame of the governance models we have inherited. These matters have been discussed in the public management literature intensely for the last two decades. My purpose here is to highlight some of the key themes from this vast literature. One of the most-quoted contributions to the public management literature is Benington and Hartley’s (2001) distinction between bureaucracy or ‘traditional’ public administration, the ‘new’ public management and ‘networked governance’ (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1: Competing paradigms: changing ideological conceptions of governance and public management

These three ideal types of public governance are in many ways artificial distinctions, since one would be hard pressed to find any contemporary Western public sector organisation that did not display some form of hybrid, or mix them all. Before exploring the current search for the next paradigm I will briefly characterise the key tenets of traditional public administration and the new public management, respectively.

By some accounts, bureaucracy ‘appears to be responsible for most of the troubles of our times’ (du Gay, 2000, p 1). Certainly, judging not just from everyday media stories or personal anecdotes but from a very large proportion of recent public management literature, bureaucratic organisations are blamed for many dysfunctions of the public sector (Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Pollitt, 2003). Indeed, Osborne and Gaebler (1992), among others, have called for the ‘reinvention’ of public organisations. Likewise, in this book I argue in favour of more innovation in government. However, as du Gay (2000, p 146) asserts towards the end of his contrastingly titled book, In Praise of Bureaucracy, when it comes to principles of bureaucracy, ‘Many of its key features as they came into existence a century or so ago remain as or more essential to the provision of good government today as they did then (…)’. What are these key factors, then?

Max Weber was the German economist, sociologist and scholar who founded the modern notion of bureaucracy. He addressed concerns about despotism by formalising organisational offices and roles and insisting that these be based on competencies explicitly underpinned by rules, laws and administrative regulations. The scope of power, the capacity to coerce others, was to be defined and limited by regulation, and the selection of people to assume positions of power ws to be determined in accordance with certifiable qualifications. Weber translated these broad ideas into specific principles; according to Wren and Bedeian (2009, pp 231–2), Weberian bureaucracy is based on the following principles.

• Division of labour: Labour is divided so that authority and responsibilities are clearly defined.

• Managerial hierarchy: Offices or positions are organised in a hierarchy of authority.

• Formal selection: All employees are selected on the basis of technical qualifications demonstrated by formal examination, education or training.

• Career orientation: Employees are career professionals rather than ‘politicians’. They work for fixed salaries and pursue careers within their respective fields.

• Formal rules: All employees are subject to formal rules regarding the performance of their duties.

• Impersonality: Rules and other controls are impersonal and uniformly applied in all cases.

Certainly, to Max Weber, bureaucracy not only leads to a number of positive outcomes but is a necessity for the functioning of modern capitalist societies. As a modern organisational necessity, the Weberian bureaucracy allegedly leads to at least four positive results (Weber, 1964; du Gay, 2000):

• efficiency

• predictability and reliability

• procedural fairness

• equality and democracy.

A key point to note here is that the production of public outcomes, understood as changes in the experience or behaviour of people, business, communities and societies, does not seem to be considered by Weber as an important result in its own right. In other words, the ability of bureaucratic governance to lead to better health, learning, growth or a better environment is not considered very clearly in Weber’s writing.

According to Weber, the establishment of a bureaucracy does lead to one potentially important societal outcome, in that it ‘favours the levelling of social classes’. He describes this as a virtuous circle where the levelling of social classes in turn positively affects the development of bureaucracy by eliminating class privileges, which makes it less likely that ‘occupation of offices’ happens based on belonging to a certain class or the size of personal means. This process ‘inevitably foreshadows the development of mass democracy’ (Weber, 1964, p 340). The efficiency of bureaucracy, in other words, is a prerequisite for effective democracy.

However, as I discussed in Chapter Two and will develop further below, the critique of the ability of bureaucratic organisations to cope with emergence and change has been rising. As I documented in my previous book, Leading Public Sector Innovation, the bureaucratic model of governance leads to a range of significant barriers or constraints to innovation in government at numerous levels: the political context (which means that objectives are usually politically given and prone to significant change outside of the public manager’s control); the lack of regular market competition and multiple value types, making it difficult to measure and assess the success or failure of government initiatives (Wilson, 1989); limited ability to make and shape long-term strategy (Mulgan, 2009; Doz and Koskonen, 2014); hierarchical and bureaucratic organisational structures; limited and often inefficient leveraging of new information technology; and (too) homogenous a composition of managers and staff, to name just a few (Osborne and Brown, 2005; van Wart, 2008; Bason, 2010; Doz and Koskonen, 2014).

Current government systems, drawing on their bureaucratic legacy, have largely been built to ensure efficiency, predictability, objectivity and stability – and mass delivery – over adaptation, flexibility, dynamism and more individualised approaches. However, the issue of identifying different and more effective models of governance may not be a question of abandoning existing models and institutions without having anything to place instead. In Marco Steinberg’s perspective (2014, p 99), the challenge is that

to manage a shift towards new competencies, cultures, incentives, and resource allocation models, cannot happen at the expense of the current delivery needs and long-term stability. As such the core issue is to design coherent transitions whereby current obligations can be fulfilled while simultaneously building necessary future ones.

What Steinberg proposes here, in line with Agranoff (2014), is that the introduction of different or new approaches within a government context never happens on a blank canvas. Managers must take account of context, of what is already there, in order to enable sustainable change. A potential problematic part of our current public management legacy is, then, that we may not truly possess the strategies, tools and processes allowing us to make such ‘coherent transitions’. As Bourgon (2008, p 390) points out, in spite of the emergence of new articulations of what governance is or could be, ‘Public sector organisations are not yet aligned in theory and in practice with the new global context or with the problems they have for their mission to solve’.

The new public management, which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, offered a compelling set of principles that set off what has arguably been a world-wide public sector reform movement that has continued to this day (Hood, 1991; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992). The British academic Christopher Hood first coined the term in his seminal article ‘A public management for all seasons’ (Hood, 1991). However, probably the most central work driving this movement was Osborne and Gaebler’s seminal work of 1992, Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector. It is worth noting that the ‘burning platform’, or hopes for change formulated by Osborne and Gaebler, was strikingly similar to the arguments made today by proponents of the emerging management paradigms. For instance, consider this quote (Osborne and Gaebler, 1992, p 15):

Today’s environment demands institutions that are extremely flexible and adaptable. It demands institutions that deliver high-quality goods and services, squeezing ever more bang out of every buck. It demands institutions that are responsive to their customers, offering choices of non-standardized services; that lead by persuasion and incentives rather than commands; that give their employees a sense of meaning and control, even ownership. It demands institutions that empower citizens rather than simply serving them.

In Reinventing Government, Osborne and Gaebler introduced 10 principles for new public management that they felt described some of the most innovative and forward-thinking public organisations of their contemporary society. In other words, they offered not so much ideas about what should be done to ‘reinvent’ the state; they showed what was already happening. Among the principles, there was a strong emphasis on learning from the private sector and benefiting from the introduction of market mechanisms and principles into public service provision. The promotion of competition between service providers and the reframing of citizens as customers, who should be given a range of choices, were each devoted significant treatment in the book. In essence, the market mechanism, according to Osborne and Gaebler (1992, pp 19–20), should replace bureaucratic mechanisms. They even suggest that public organisations should get into the business of ‘earning money’ rather than only spending it. Additionally, public organisations should measure their performance not on the basis of their expenditures (inputs) or activities but on the basis of the results and outcomes they generate.

As we shall see below, the market-oriented tenets of the new public management have been extensively criticised in the context of the current debate on the next governance paradigm. For the most comprehensive critique to date, Christopher Hood and Ruth Dixon’s evaluation of 30 years of new public management reforms in the UK is a key resource (Hood and Dixon, 2015). What is perhaps less well recognised is that Osborne and Gaebler also posited some of the same principles as are being discussed and promoted by the ‘next’ governance school. For instance, they argued for more mission-driven goals, prevention, and decentralisation of authority. And with a suggestion that resonates with today’s discussions on networks, co-production and collective impact, Osborne and Gaebler highlighted the need for government organisations to catalyse a wide span of sectors (public, private, civic) to address problems and create lasting impact.

Different ways of framing the next paradigm that could replace or supplement bureaucracy and the new public management abound, and go beyond the title provided originally by Benington and Hartley: ‘governing by network’ (Goldsmith and Eggers, 2004); ‘co-production’ (Alford, 2009); ‘collaborative governance’ (Paquet, 2009); ‘a new synthesis’ (Bourgon, 2011); ‘collaborative innovation’ (Ansell and Torfing, 2014); and ‘strategic agility’ (Doz and Koskonen, 2014). As Peters (2010, p 145) asserts:

If bureaucracy has declined as a paradigm for the public sector, however, it has not been replaced with any single model that can provide descriptive and prescriptive certainty. Neither scholars attempting to capture the reality of contemporary public administration, nor politicians and managers attempting to make the system work on a day to day basis, have any simple model of what the contemporary reality is.

Rather than a simple or single model for the next governance approach, a number of different models are currently in play. Christensen (2012) suggests that the organisational forms of public management have become increasingly complex and multifunctional. In a paper titled ‘Ideas in Public Management Reform for the 2010s’, Carsten Greve (2015) describes three self-styled conceptual alternatives from the literature on public management. ‘Self-styled’ refers to the fact that these are all explicitly describing themselves as alternatives to the new public management. It is useful, for the purpose of this book, to expand a bit on these conceptual alternatives, as to some degree they make up the playing field onto which new approaches catalysed by design processes would necessarily enter. The next governance model is not a blank space, it is already full of ideas, suggestions, frameworks and approaches – some based on empirical practice, others perhaps still more theoretically informed. Greve (2015) proposes the following alternatives of what might be termed ‘emergent public management’:

• Digital-era governance, which has mainly been formulated by Patrick Dunleavy (Dunleavy et al, 2006). Key components in this governance thinking are obviously the opportunities raised by digital (e-government) services, including issues of transparency, social media and shared service centres. Dunleavy et al characterized digital-era governance as being composed of three elements (Dunleavy et al, 2006). First, the roll-back of agencies, joined-up governance, re-governmentalisation, reinstating central processes, radically squeezing production costs, re-engineering back-office functions, procurement concentration and specialisation and network simplification. Second, a needs-based holism, including client-based or need-based reorganisation, one-stop provision, interactive and ask-once information seeking, data warehousing, end-to-end service re-engineering, agile government processes. And third, ‘digitisation’ processes among others including electronic service delivery, new forms of automated processes, active channel streaming, facilitating co-production, moving toward open-book government.

• Public value management, which has been suggested by Benington and Moore (2011). Here the key themes include strategy making, performance governance and innovation and strategic human resource management. This strand of governance thinking builds in part on Mark Moore’s earlier work on public value (Moore, 1995). In terms of strategy making for public value creation, according to Greve, Benington and Moore place public managers in ‘a strategic triangle’ between a legitimising and authorising environment, an organising environment in their focus and an environment of results; that is, efforts to produce results that are, in effect, a value-creation process. Greve (2015, pp 55–6) suggests (also referencing Alford and O’Flynn) that the public value management framework has something different to offer than new public management. Whereas new public management is competitive government, public value management is post-competitive; it focuses more on relationships, sees collective preferences as expressed, sees how multiple objectives are pursued, including service outputs, satisfaction, outcomes, trust and legitimacy, sees multiple accountability systems. Whereas the preferred system of service delivery under the new public management paradigm is the private sector or tightly defined arm’s-length public agencies, public value management’s delivery system ‘is a menu of alternatives selected pragmatically’. New public value management also expands on the notion of ‘performance governance’ as an integrated, institutional framework that includes use of data for managing not only performance but also transparency. Finally, according to Greve (2015, p 56), ‘The innovation agenda can be accommodated in the discussion of public value management as Moore emphasized the strategic and innovative aspects of public management in his writings.’

• Collaborative governance, or new public governance. Here it is scholars such as O’Leary and Bingham (2009), Osborne (2010), Donahue and Zeckhauser (2011) and Ansell and Torfing (2014) who formulate the paradigm. Some of the central concepts here are networks and collaboration, public-private partnerships and new ways of engaging active citizens. Greve (2015, p 58) points out that new public governance can be viewed as an overarching theory of institutionalised relationships within society, not least when it comes to relations between public organisations and the for- and not-for-profit sectors. New public governance hereby focuses attention on partnerships, networks, joined-up services and new ways to work together. The numerous ways that citizens can become active and enter into co-producing relationships are key (Alford, 2009; Newman and Clarke, 2009). In this paradigm, the strategic orchestration of public-private partnerships, allowing sharing of risk or leveraging of resources, is also a key theme. Finally, when it comes to citizen engagement, new public governance suggests that efforts can be stepped up and become more systematic.

Carsten Greve’s account of the state of the art indicates that the search for the next governance paradigm is still very much on-going. However, some patterns seem to stand out across the three alternatives described above. In a summary of ‘post-new public management’ reform efforts, Tom Christensen (2012) argues that new governance elements and networks are supplementing hierarchy and market as coordination mechanisms. Organisational forms such as partnerships and collegial bodies spanning organisational boundaries are being used more intensively. Networks have been introduced in most Western democracies as a way to increase the capacity of the public sector to deliver services (Klijn and Skelcher, 2008). Christensen further suggests that there is a state-centric approach to governance in which public-public networks are a main component (Peters and Pierre, 2003). Here civil servants have networking and boundary-spanning competences allowing them to act as go-betweens and brokers across organisational boundaries both vertically and horizontally. Additionally, public-public networks bring together civil servants from different policy areas to trump hierarchy (Hood and Lodge, 2006), that is, they are facilitators, negotiators and diplomats rather than exercising only hierarchical authority, which may be especially important in tackling ‘wicked issues’ that transcend traditional sectors and policy areas.

The avenue certainly seems open for an exploration of what design approaches really involve, when it comes to implications for the future of public governance. The critical implication is that public managers may need to discover for themselves what is the contemporary reality they need to relate to, and govern in, and then make their own judgements as to the right approach.

That being said, the distinction between different governance paradigms allows us to characterise different structures, processes and organising principles that we may find in our public institutions; and it also allows us to ask what a more ‘modern’, or perhaps ‘postmodern’ or ‘re-enchanted’, organisation based to a higher degree on networked governance might actually look like. Since 2000, if not earlier, the public management debate not only in academic but also in practitioners’ circles began to shift towards the ‘networked governance’ paradigm. From Goldsmith and Eggers’ volume on Governing by Network (2004) to Bruno Latour’s dry observation that it is time to lay new public management’s implicit attack on the state behind us,

It is amazing that such a dispute could have passed for so long as a serious intellectual endeavour, so obvious is it for us now, that there is no alternative to the State – on condition of rediscovering its realistic cognitive equipment. (Latour, 2007, p 3, original emphasis)

It is exactly this question of ‘rediscovering the state’, perhaps even more so than ‘reinventing it’, that this book explores. The question becomes one ofhow to accommodate the need for a broader and perhaps different vocabulary and, dare one say it, concrete practices for problem solving and for navigating the process towards some different model of governance.

I opened this book by suggesting that the worlds and cultures of public management and design were akin to two waves crashing against each other, as if these two different domains of knowledge and professional practice could not fruitfully co-exist. However, I believe this account demonstrates that perhaps the most powerful crash is not necessarily between public management and design per se, but between the ‘scientific’, bureaucratic and decision-making foundations of public management, on the one hand, and the societal context in which we now live, on the other hand. Is it, rather, a clash between a globalised, fast-paced, 21st-century world infused with technology being governed by institutions designed at the dawn of the 20th-century? Is it the widening gap between the nature of our world and the design ‘blueprint’ of government that is the real challenge? Is the problem that – to paraphrase Colander and Kupers (2014) – using ever-more refined tools, we have climbed to the top of the mountain of bureaucratic management, only to discover from the top of the pinnacle a very different mountain? Is the issue, as we are beginning to explore a different kind of governance paradigm, that it is an entirely different mountain that must be climbed? And does this particular mountain have more in common with the collaborative design approaches toward which the pendulum is swinging today?

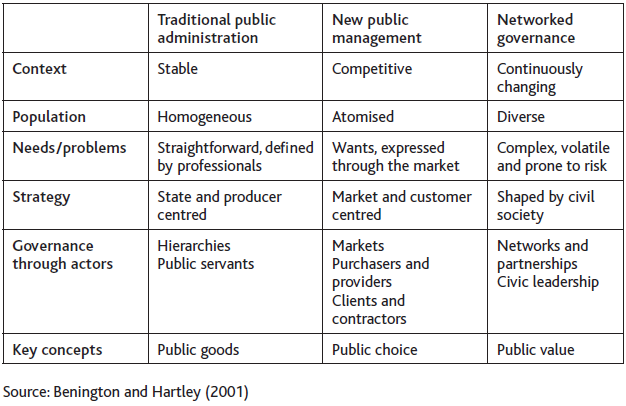

My point is this: as regards the emerging forms of governance and design, there are signs of convergence. Building on this chapter and the previous one, what kind of agendas are emerging at the intersection between design and public management?

Design seems to be moving closer to public organisations, and public organisations are, perhaps, opening up to design. Whereas public management may need to begin an ascent of an entirely new mountain, based on something different than bureaucratic governance and rational decision making, design may have to ascend a similarly different mountain, characterised by the new roles of designers as stewards, co-creators and social innovators.

Table 4.2 summarises some of the key shifts happening within public management and design, as discussed here and in the previous chapter, and proposes how they relate.

First, we have seen that public management is opening up: management practice and theory are becoming increasingly receptive to the messiness, complexity and unpredictability of the policy environment. As Peters (2010) argues, that ambiguity may not be a bad thing. There may be advantages, not least ‘that the latitude for action by the individual is enhanced’ (2010, p 156). Recognising the widening gap between the policy levers and tools currently available to managers, in particular within the context of the call for ‘innovation’ in times of turbulence and austerity, public organisations and their managers are becoming receptive to new ways of doing things, even if they do not know exactly what they are searching for (Goldsmith and Eggers, 2004; Bourgon, 2012; Ansell and Torfing, 2014). As Peters (2010) suggests, they may also be granted, or be increasingly able to grab, the agency needed to engage in that search. As discussed above, the missing link between the current governance paradigms and a future one seems to be the approaches, methodologies and ways of thinking that can drive the process and make the transition towards a different future state. This opening up happens as the design discipline is also opening to making a contribution in the policy and social sectors – taking a ‘social turn’ in terms of context and interest.

Table 4.2: Convergence of public management and design

Second, public management may already be becoming more balanced, in search of a ‘new synthesis’ that accommodates more complex and individualised user (citizen, business) needs and adopts structures, processes and technologies to support this shift (Goldsmith and Eggers, 2004; Bourgon, 2012). Focusing on outcomes for citizens, or public value (Moore, 1995; Cole and Parston, 2006), has become increasingly the ‘new black’ in many public organisations. Similarly, we saw a shift in design’s role in industrial society, in part driven by digitisation, to facilitate much more tailor-made and individually oriented ‘co-creation of value’. The professional design community itself would certainly argue, as Angela Meyer does (2011, p 188), that ‘design is fundamentally about value creation’. Of course, this does not entail, that all is good just by focusing on ‘value’, or outcomes, understood as the results flowing from public interventions, as both Moore and Cole and Parston would argue. As we saw in the analysis of Weber’s principles of bureaucratic organisation, there are other aspects of public organisations that are at stake and that may be at odds with a strong emphasis on outcomes. What happens, for instance, with principles of equality or, for that matter, with efficiency?

Third, as public organisations and their managers are on the search for new process tools, design is transforming: it is taking new forms and is beginning, as a practice and profession, to lend itself to new applications, contexts and roles, also in the domain of public service and policy design (Meyer, 2011; Ansell and Torfing, 2014; Sanders, 2014). The ‘social and political turn’ in design is happening in sync with a ‘collaboration turn’ towards increased co-design with stakeholders and users. So, designers, as professionals, are finding themselves increasingly in the role of process designers, facilitators, stewards and orchestrators. Meanwhile, public managers find themselves cast into increasingly complex circumstances in which they are expected to find effective courses of action. In these circumstances, managers are searching for the tools, approaches and perhaps even paradigms that can help them achieve their stated goals.

Fourth, whereas the term ‘innovation’ has helped to open up and perhaps legitimise the search for ‘new public futures’ (Christiansen, 2014), managers need to somehow give form, substance and direction to this search. To some extent, this type of search for methodologies and tools to support a paradigm shift has happened before, but in a different context. With the evaluation and performance management movement in the 1990s and 2000s, public managers increasingly accessed tools that could increase transparency, accountability and organisational learning under the overall guise of the new public management. Later, with the lean management ‘toolbox’ that became strong in the 2000s in the public sector, managers gained access to efficiency- and error-reducing methodologies (essentially, process-innovation tools) that were suited to certain contexts and problems as well. Both of these broad domains of management techniques seem to have fitted quite well with the dominant new public management paradigm, along with Weber’s bureaucratic principles of rationality, efficiency and predictability. But what kinds of approaches and methodologies are set to accompany, or perhaps to help realise, an emergent networked ‘new’ public governance paradigm? Just as the arc of design practice has come round to a more individual and tailored understanding of consumption, interaction and use, so is Benington and Hartley’s concept of networked governance – and the other forms of ‘new’ approaches discussed in contemporary academic circles – also associated with increased ‘citizen-centricity’ and differentiation as one-size-fits-all approaches begin to give way to more customised and flexible modes of service production (Goldsmith and Eggers, 2004; Alford, 2009; Greve, 2015).

This chapter has charted the evolution of public management from Weberian times until today and has characterised the current debate on alternative directions for the next governance model. I have also discussed how there are some surprising similarities between the developments taking place within the design profession and the emergence of new ideas about public governance.

Ultimately, my argument is that public managers are now in confusing territory. There is no blueprint, no broad consensus, as to what governance model should, or will, replace the new public management. In this situation, multiple models are being floated and offered to public organisations all the time, while our legacy model, bureaucratic governance, inherited from over a century ago, is still very much around. Can we expect that a clearer picture of the appropriate governance approach will emerge, or can we expect more ‘overlays’ of different models?

As a public manager, it could be relevant to reflect on the following.

• What characterises the governance set-up that your organisation is currently part of? How would you place it in relation to the three ideal-types of governance models – bureaucratic, new public management or networked governance (or the like)? What is the balance? Do you experience one of the models as more prevalent than the others? What are the factors (chains of command, measurement systems and data, contracts, financial arrangements, etc) by which you judge the kind of governance model that dominates your organisation?

• In what ways is your current governance model positively contributing to your ability to carry out your mission and solve and address the challenges you face? To what extent is your current governance set-up part of the problem? What would have to change to make your governance approach more fit for purpose? If something needs to change, what key questions should you start with?

• How would you hope to benefit by transforming your current governance model? What opportunities might you realise, and what would be the risks involved? At a personal level, what could motivate you to experiment with a different way of governing?