The Indo-Pak Wars

‘….close to the area, we descended fast, looking all around and below us for the enemy aircraft. At about this time we also learnt that the C-in-C was flying around the area in a L-19. We did not see him; we later on discovered that he left well before we got there. Our search succeeded and I saw two enemy aircraft. They were crossing underneath us and I informed Rafiqui about it. He immediately acknowledged it ‘… contact’. Rafiqui said he was going for them. While covering his tail, I spotted two Canberras 9 o’clock from me at 5,000-6,000 feet. Then I spotted another two Vampires trying to get behind Rafique. I instinctively broke off and positioned myself behind these two. In the meantime, Rafiqui had knocked down one of his two targets and was chasing the other. About now I had my sights on one of my own and was holding my fire. I was anxiously waiting for my leader to bring down his second and clear out of my way. When the Vampire I had targeted closed in on Rafiqui too dangerously, I called out to him break left. Within the next moment Rafiqui shot down his second, reacting to my call and broke left. Simultaneously I pressed my trigger and hit one of them. Having disposed of one I shifted my sight on the other and fired at him. In the chase I had gone as low as 200 feet off the ground when I shot my second prey, he ducked and went into the trees. We had bagged four in our first engagement with the Indians…’

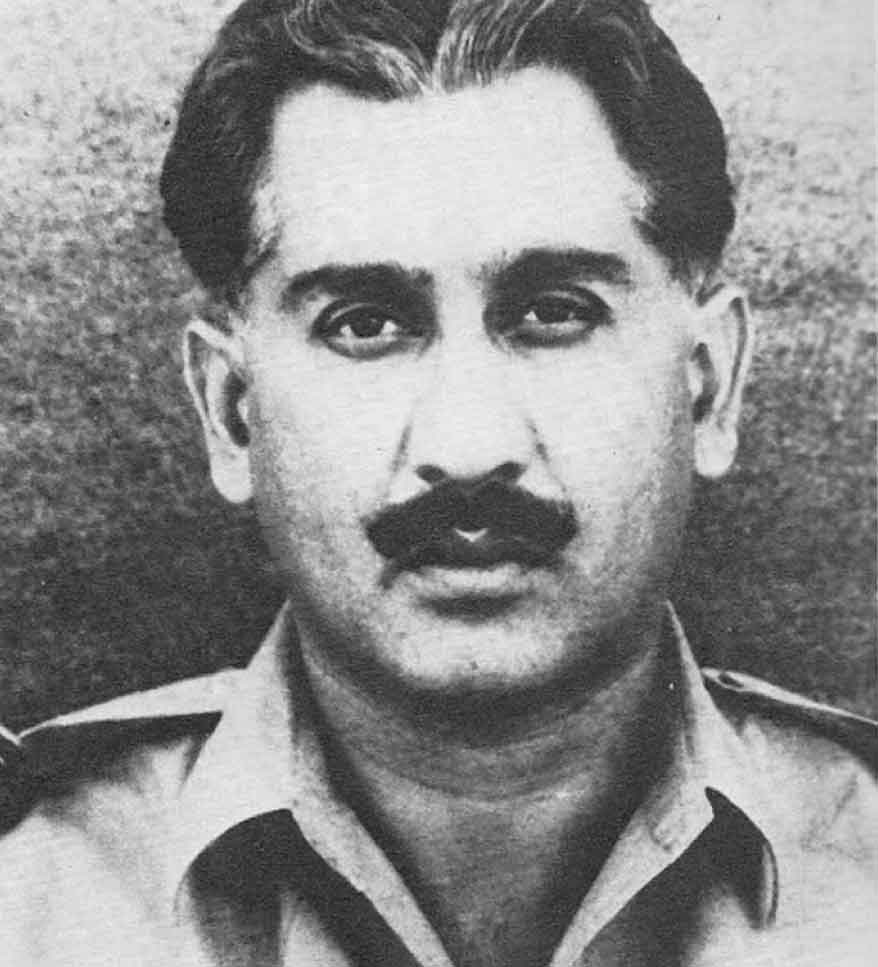

Flight Lieutenant Imtiaz Bhatti, F-86 Sabre pilot, 5 Pakistan Air Force (PAF) Squadron, 1 September 1965. As an exchange pilot in the UK his OC, Squadron Leader Sarfraz Ahmed Rafiqui flew Hunters for two years. Sarfraz’s OC on 19 Squadron RAF, reporting on his flying abilities, wrote: ‘In the air his experience and skill combine to make him a very effective fighter pilot and leader who creates an impression of disciplined efficiency in all that he does’. On return to Pakistan in 1962 he was given command of 14 Squadron. A year later, he was given command of the elite 5 Squadron. He became well known for his highly assertive and effective control of the unit as much as for his spirited attitude towards flying.

Sunset was only about an hour and a quarter away on 1 September 1965 when a forward airfield in the Punjab suddenly came to life with the noise of jet engines starting up. In sections of four, with a few minutes interval between each section, twenty-eight fighter-bombers of the Indian Air Force took off for the Chamb sector in the Jammu and Kashmir area, to help stem the unexpected thrust of Pakistani armour which had crossed the international border into Jammu. This was the start of the air action by the Indian Air Force which, when it ended on 23 September, had cost the Pakistan Air Force seventy-three aircraft destroyed in the air and by ground fire. This figure does not include aircraft destroyed or damaged during the numerous night attacks carried out by Indian bombers on Pakistani air bases. Indian losses during the same period were only thirty-five aircraft. The need for the Indian Air Force to go into action had been made imperative by the Pakistani action in spearheading its attack across the international border and the cease-fire line with almost two regiments of tanks in the Chamb sector. In this first strike by the Indian Air Force, fourteen tanks were destroyed or damaged; eleven were actually seen burning. In addition thirty to forty heavy vehicles were also destroyed. After this engagement, however, two Indian Vampires were missing and two more had been damaged.26

Camera-gun sequence showing the destruction of a PAF F-86 over Halwara on 6 September 1965 by Flying Officer V. K. Neb of 27 Squadron IAF who was flying a Hunter F.56 on a dusk patrol with Flight Lieutenant D. N. Rathore when an emergency call that Halwara airfield was under attack made them rush to base. About the same time two Sabres flown by Flight Lieutenants’ Yunus Hussain and Cecil Choudary were exiting the raid. As the Hunters jumped them Neb latched onto Hussain’s Hunter and destroyed it with a one and a half second cannon burst, earning his first Sabre Kill. Neb had to wait another six years until he could claim another IAF Hunter.

On 3 September 1965 an IAF Gnat (seen in left with a F-86 Sabre) flown by Squadron Leader Brijpal Singh Sikand surrendered to a 9 Squadron F-104 Starfighter during an air combat. The Indian pilot landed at Pasrur airfield near Gujranwala and was taken prisoner. Later Squadron Leader Saad Hatmi flew the captured Gnat from Pusrur to Sargodha and it is now in the PAF museum in Karachi.

Since Partition of British India in 1947, Pakistan and India remained in contention over several issues, not least the disputed region of Kashmir. On 5 August 1965 between 26,000 and 33,000 Pakistani soldiers crossed the Line of Control dressed as Kashmiri locals headed for various areas within Kashmir. Indian forces, tipped off by the local populace, crossed the cease fire line on 15 August. Initially, the Indian Army met with considerable success, capturing three important mountain positions after a prolonged artillery barrage. At that time the Pakistan Air Force had about 140 combat aircraft, mostly American-built, including the F-104As of 9 Squadron. Pakistan acquired its Starfighters as a direct result of the Soviet downing of an American Lockheed U-2 spy plane that had been based at Badaber (Peshawar Air Station) on 1 May 1960. The aircraft, flown by Central Intelligence Agency pilot Francis Gary Powers, was performing aerial reconnaissance when it was hit by an S-75 ‘Dvina’ (SA-2 ‘Guideline’) surface-to-air missile and crashed in Sverdlovsk.27 Understandably annoyed at the Pakistanis for allowing the Americans to use their country as a base for espionage missions, the Soviets threatened to target Pakistan for nuclear attack if such activities continued. Taking the threat seriously, the United States agreed to provide Pakistan with enough surplus F-104A interceptors to equip one squadron. Although the F-104As were intended to defend Pakistan against high-flying Soviet bombers coming over the Hindu Kush Mountains, their actual combat use would be under quite different circumstances. The PAF’s fighter force comprised 102 F-86F Sabres and twelve F-104 Starfighters, along with 24 Martin B-57 Canberra bombers.28 B-57s flew 167 sorties, dropping over 600 tons of bombs. Three B-57s were lost in action, along with one RB-57F electronic intelligence aircraft. However, only one of those three was lost as a result of enemy action. During the war, the bomber wing of the PAF was attacking the concentration of airfields in north India. In order to avoid enemy fighter-bombers, the B-57s operated from several different airbases, taking off and returning to different bases to avoid being attacked. They would arrive over their targets in a stream at intervals of about 15 minutes, which led to achieving a major disruption of the overall IAF effort. The unknown Pakistani flying ace, ‘8-Pass Charlie’, was named by his adversaries for making eight passes in the moonlight to bomb different targets with each of the B-57’s bombs.

On 13 September 1965 Squadron Leader Alauddin ‘Butch’ Ahmed of 32 Wing, PAF was flying an F-86 in a low level raid against the freight wagons in the goods yard at Gurdaspur Station. On a second pass at very low level through smoke from previous strikes his aircraft was hit by fragments from the exploding trucks and twelve miles away from Pakistani territory he reported that his cockpit was full of smoke. He continued to fly his damaged aircraft westwards before finally ejecting from his burning Sabre. He did not survive. There is conjecture as to whether he was shot while descending in his parachute in the combat area.

Facing the PAF was the Indian Air Force (IAF), with about 500 aircraft of mostly British and French manufacture.29 In January 1957 India placed a large order for the Canberra; a total of 54 B(I)58 bombers, eight PR.57 photo-reconnaissance aircraft and six T.4 training aircraft were ordered, deliveries began in the summer of that same year. Twelve more Canberras were ordered in September 1957; as many as thirty more may have also been purchased by 1962. First used in combat by the IAF in 1962, the Canberra was employed during the UN campaign against the breakaway Republic of Katanga in Africa. The most audacious use of the bomber was in the raid on Badin when the IAF sent in the Canberra to attack a critical Pakistani radar post in West Pakistan. The raid was a complete success, the radars in Badin having been badly damaged by the bombing and put out of commission. A later raid by the IAF was attempted on Peshawar Air Base with the aim of destroying, amongst other targets, several Pakistani American-built Canberras. Due to poor visibility, a road outside of the base was bombed, instead of the runway where PAF B-57 bombers were parked. The IAF had also begun to acquire MiG-21Fs, new Soviet interceptors capable of Mach 2, but only nine of them were operational with 28 Squadron in September 1965 and they saw little use.

Captain (later Air Commodore) Rahat Hussain PAF.

IAF Gnat pilots in front of one of their aircraft.

On 1 September Pakistan launched a counter-attack, called Operation ‘Grand Slam’ with the objective to capture the vital town of Akhnoor in Jammu, which would sever communications and cut off supply routes to Indian troops. Attacking with an overwhelming ratio of troops and technically superior tanks, Pakistan made gains against Indian forces that were caught unprepared and suffered heavy losses. India responded by calling in its air force to blunt the Pakistani attack. That evening saw hectic and desperate attempts by the IAF to stop the rapid advance of PAK Army’s 12th Division offensive against Akhnoor. Vampire Mk 52 fighter-bombers of 45 Squadron, which moved from Poona to Pathankot were hastily called into action. The obsolescent Vampires had been considered suitable for providing close support in the valleys of Kashmir but though they were put on high alert during the Sino-Indian War of 1962 they did not see any action, as the air force’s role was limited to supply and evacuation. The grim situation on the ground found the Vampires at work immediately. Three strikes of four Vampires each (along with some Canberras) had been launched in succession that evening and were successful in slowing the Pakistani advance. Major General G. S. Sandhu in his book ‘History of Indian Cavalry’ recounts how the first Vampire strike of four ‘leisurely proceeded to destroy three AMX-13 tanks of India’s own 20th Lancers, plus the only recovery vehicle and the only ammunition vehicle available during this hard-pressed fight. The second flight attacked Indian infantry and gun positions, blowing up several ammunition vehicles’. One was shot down by ground fire. Then an element of two Sabres armed with air-to-air missiles arrived on the scene; in the ensuing dogfight, the outdated Vampires were outclassed.

Squadron Leader Sarfraz Rafiqui, the plucky and outstanding OC of 5 Squadron, and Flight Lieutenant Imtiaz Bhatti were patrolling at 20,000 feet near Chamb. On being vectored by the radar, they descended and picked up contact with two Vampires in the fading light. Rafiqui closed in rapidly and before another two Vampires turned in on the Sabres, made short work of the first two with a blazing volley from the lethal 0.5 Browning six-shooter. Then, with a quick-witted defensive break he readjusted on the wing of Bhatti, who got busy with his quarry. While Rafiqui cleared tails, Bhatti did an equally fast trigger job. One Vampire nosed over into the ground which was not too far below; the other, smoking and badly damaged, staggered for a few miles before its pilot, Flying Officer Pathak, ejected. The less fortunate Flight Lieutenants A. K. Bhagwagar, M. V. Joshi and S. Bhardwaj went down with their Vampires in full view of the horrified Indian troops. The IAF immediately withdrew from front-line service about 130 Vampires, together with over fifty Dassault Ouragan ‘Toofani’ jet fighter-bombers.30 The IAF was effectively reduced in combat strength by nearly 35% in one stroke, thanks to Rafiqui and Bhatti’s marksmanship.

Chandrakant Nijanand Bal, a young pilot on 31 Squadron IAF who flew the Mystère IVa fighter bomber during the 1965 war, distinguished itself operating from Pathankot on 1 September.

‘Time 1730 hours. Twenty odd faces could be seen in the briefing room. The Officer-in-charge flying entered the room and closed the door behind him. He paused, head cocked to one side in his usual fashion. ‘Boys, we have got the green light. The Pak army, with 90 tanks crossed the border this morning in the Chamb Sector’ and he indicated a small bulge on the quarter inch map. ‘Your job is to stop them. The Ground Liaison Officer will take over from now.’ The GLO completed his briefing and the pilots took down the details on their maps and hurried to their respective squadrons. I had been recalled from leave some days previously. I had just spent about three weeks at home. The daily newspaper used to bring news of ‘kills’ by our security forces. One could feel the mounting tension. I reached my squadron on 27 August. Sethi was the first to meet me. ‘You missed some sorties over the valley while on leave” he said. I knew he meant the Srinagar Valley. I was looking forward to some good flying. However, things worked out differently. Flying was stopped and the airmen worked feverishly to get the maximum number of aircraft on the flight line. The Navigation Officer of the Squadron was burdened with the number of maps being issued. We were giving the final touch to the ‘cutting edge.’

Footage captured by Flight Lieutenant Imtiaz Bhatti’s gun-camera on 1 September 1965 of Squadron Leader Sarfraz Ahmed Rafiqui reacting to Bhatti’s ‘break’ call near the River Tawi at the foothills of the Parmandal Range after he had shot down two Vampires.

‘Early morning, 1 September I was standing by for a patrol sortie in the Valley. I listened to the briefing, inwardly wishing I were in the formation. The sortie went off without a hitch. It’s 10 o’clock and Tony passes the word that Gurdaspur has been shelled. We celebrated our Squadron’s second anniversary by a special lunch. There is a cake for the occasion baked by ‘Mrs Boss’ [Wing Commander Jimmy Goodman’s wife] and we made short work of the ceremony. Five o’clock and the word goes around. I leapt to my feet and made it towards the briefing room. Tony reminded me that I have forgotten my map. I ran back and fetched it, not wishing to miss any part of the briefing.

Squadron Leader Amjad Yunus Hussain Khan fought in air battles aggressively, fearlessly and with great professional skill. During one such engagement he fought singly against six IAF aircraft and claimed two Hunters. Though his own aircraft was damaged in this encounter, he managed to bring it back to base safely. On 6 September 1965, while attacking Halwara airfield, his small formation was intercepted by a large number of IAF and, although his aircraft was hit, he refused to break off the engagement, in complete disregard of personal safety, and was reported missing from this mission. For his gallantry, valour, professional skill and devotion to duty he was awarded the Sitara-e-Jurat.

‘I was once again standing by for the first section, and felt bad about it. It must have shown on my face for Tony said that I could join the second section. I went to my aircraft well before time and inspected it. Under each wing is a pod containing rockets. I had never fired this before and mentally go through the briefing, ‘Circuit breaker IN, Wing Master ON, lift flap and press.’ I was pleased with myself. I now saw the first section of Vampires getting airborne. It was time to strap-up. My section took off and I switched off the engine. Peachy came on my scooter and asked me to hop on. I am to fly another aircraft. I strap-up for the second time. Just as I started the engine Tony came running to my aircraft. He was supposed to be in the first section but I did not think of that then. He signalled me to get out. Something must have gone wrong. I did as I was told and cursed, and went back fuming to the Squadron. I must have looked a sight.

Gun-camera sequence showing a PAF Sabre going down in flames.

‘That day twenty-eight sorties were flown. That must have been a good blow to the advancing tanks, for their progress was slowed down. We lost Horsey Bharadwaj that day. News of three others was yet to come.’

The next day, Pakistan retaliated; its air force attacked Indian forces and air bases in both Kashmir and Punjab. Chandrakant Bal started the next day early. ‘The duty bearer woke me up at three o’clock. I dressed quickly and reported to Wing Commander Goodman in the Mess, as instructed. Both the Station Commander and he had been busy during the night. I could see that plainly, as fatigue is quite visible on their faces. The Station Commander explained the situation to me. I am to go with the Boss to Chamb at first light for a reconnaissance of yesterday’s battlefield. We are to have escorts for our protection. A final briefing and a time check and we were off to our aircraft. We took off at dawn and made for the target area, flying low, just above the trees to avoid enemy radar detection. As we neared Chamb I spotted four Sabres but kept quiet, as there was no immediate danger. The Sabres were orbiting the battle area. A quick check on the sabres and we started our reconnaissance ‘literally under their noses.’ The enemy aircraft had not yet seen us and Boss called ‘Buster port’ and all of us veered sharply to the left and opened up power. We are now on our way back. After reaching base I climbed out of the cockpit soaked in sweat. I breathed in the cool morning air and felt good. A few words of praise to the airmen and I was on my way for the debriefing. I met Sethi after the debriefing. He had flown yesterday and got a tank. He asked how the mission had gone and I narrated the tale. The next three days saw little other activity except more strikes in the Chhamb Sector. Every day the scores went up a little. We were hitting anything on wheels. Even a few camps were detected and fired upon. These especially were very difficult to see from the air as they were well camouflaged.’

On 3 September came the break-through, which marked the start of the superiority which the Indian Air Force maintained throughout the rest of the campaign. At 7 am that day a formation of Pakistani fighters was reported to be circling over Indian Army positions in the Chamb sector. A section of Gnats was scrambled to intercept the enemy. Thirty-four year old Squadron Leader Trevor Keeler VSM,31, born on 8 December 1934 in Lucknow who was leading the section, sighted the enemy and identified them as F-86 Sabres. Trevor, who had an elder brother, Denzil, who would also be honoured for his service in the IAF, immediately engaged them. While Keeler was jockeying for position, the F-86s were joined by some Pakistan Air Force F-104s. But in spite of being face to face with reputedly superior aircraft, Keeler refused to break off and finally lining up a Sabre in his sights, shot it down. The next day another two Pakistani Sabres were shot down over the same area.

On 6 September when the Indian Army marched into the Lahore sector to forestall an attack in the Punjab the IAF was called upon to give ground support and try to disrupt the logistics of the Pakistani Army. Until then the IAF had not attacked any air bases. Chandrakant Bal recalled:

‘We woke to the sound of artillery guns. The western horizon was aglow and we were informed about the advances being made by our ground forces in the various sectors. The very same evening PAK Sabres visited our Base with unfriendly intentions. We were all sitting outside our crew room talking shop. One of our missions was seen returning. For a few moments aircraft were seen all over the circuit and they landed one behind the other. We were about to resume our discussions when Tony spots an unfamiliar looking aircraft rolling into a dive. ‘Here they come!’ he said and strode into the crew room. There was more than a little confusion with bodies colliding with one another as an effort was made to head for protection. I ran for a trench, tripped over, fell, scrambled on all fours and finally dived into it. This is done to the tune of machine gun fire from the Sabres.

‘Others later remarked that this reminded them of a scene from the film ‘From Here to Eternity.’ A moment later I felt a heavy weight crushing my legs. Looking back I saw Chandru who sheepishly said, “I hope your leg is not hurting.’ Roundy, the Squadron’s only pilot attack instructor was coolly assessing the Sabre tactics and score, sometimes saying with a frown “That’s not how it should be done.” After the raid was over we trickled out of hiding, all dusty, but with false smiles on our faces.

‘Back after our day’s work I was in the bath and have just about soaped myself when I heard the anti-aircraft guns firing. I grabbed a towel and was in a trench in no time. It turns out to be a false alarm and a kind soul gives me a handkerchief to wipe the soap out of my eyes. The soapy episode was followed the same night by the first night raid of the war. Though it stood nowhere when compared with the London or Berlin air raids of the last war, it still qualified to be classed as an air raid by virtue of the fact that a bomb fell a little to one side of the runway, causing a high degree of excitement among us. Those still clinging to the bar by candle light managed to reach the nearest trench, not forgetting to bring their glasses with them. The sky filled with red fireballs, which indicated the individual lines-of-fire of the anti-aircraft guns. In the dim light of a rising quarter moon we had a glimpse of the B-57. The raid did no damage other than disturb our sleep. This practice was to follow in all future night raids. During one such night we were disturbed three times within an hour or two in between. These raids demonstrated the unique human quality of adaptation. Never did anyone feel that this was his last day in spite of heavy odds against him. We used to sleep with one ear tuned to the siren and could sprint to the trenches in total darkness if called to do so.

‘The war had been going on for over a week now. The army was fighting a determined enemy on the ground while the Air Force battled for air superiority. Many a pilot made a ‘Nylon descent’ to safety or captivity. In this grim struggle one of our tasks was to find out what was going on behind the enemy lines. On one such mission the pilots returned and excitedly reported seeing a railway train carrying a load of tanks. This vital information was used later in an extremely successful strike on the train, thus denying to the enemy these tanks at a critical time.’32

That evening Pakistani aircraft attacked two Indian air bases. One of these attacks was on Halwara and was carried out by four F-86 Sabres. It was to prove an extremely costly venture for the Pakistanis, for none of the four Sabres returned; three F-86s were shot down by IAF Hunters and one fell victim to anti-aircraft fire. When the Pakistanis raided Kalaikunda in the Eastern sector, again with a section of four F-86s, the story of Halwara was repeated; all four were shot down, two by Hunters and two by AA. After that, the Pakistanis never ventured to attack Indian air bases in daylight. But these raids did open the way for Indian pilots to attack Pakistani airfields in retaliation. The first to be attacked by the Indian bombers were Sargodha and Chaklada on the night of 6/7 September. From then on until the cease-fire on 23 September a heavy toll in the air battles, Indian Army gunners were doing wonders with their anti-aircraft guns. Taking only one example of a single battery at Amritsar, the first attack by the PAF against this installation came on the evening of 5 September; it was driven off. In the next attack, on the 8th, one PAF aircraft was shot down. Further successes followed and by the time hostilities ceased this battery had a ‘bag’ of ten Pakistani aircraft confirmed, including B-57 bombers.

IAF Hawker Hunter F.Mk.56s of 14 Squadron with BA209 in the foreground before delivery to India.

While the Pakistanis had been effectively deterred from carrying out daylight attacks on Indian airfields and installations and targets inland, the IAF fighter-bombers ranged far and wide, attacking military targets and air bases. Sargodha airfield was attacked several times in broad daylight by Indian Mystère IVAs and Hunters. Considerable damage to the installations was done and, besides other aircraft, at least two F-104 Starfighters were destroyed or damaged. In offensive fighter sweeps, tanks, heavy guns, armoured vehicles, anti-aircraft guns, heavy motorised transport and formation headquarters fell victim to Indian rockets, bombs and cannon. During the twenty-three days’ fighting the IAF destroyed no fewer than 120 Pakistani tanks alone. In one particularly effective strike on 8 September four IAF Hunters destroyed a goods train - which action eventually resulted in the blunting of the Pakistani armour attack in the Khem Karan sector and, in addition, knocked out four tanks and over sixty vehicles. While the IAF fighter-bombers continued to give ground support to the Army, Indian fighters were busy clearing the skies of the Pakistani Sabres. Every time the F-86s were engaged by Gnats or Hunters, the Sabres were never able to get away without loss. The reputedly deadly Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, on which the PAF depended so heavily for air combat, proved ineffective because of the low altitudes at which most of the air battles were fought. More often than not, the enemy fighters had to jettison these missiles when engaged by the Gnats.

In fact the greatest single deterring factor in the air battles proved to be this British-designed lightweight high-performance fighter which has been under licence-manufacture in India since 1956. It was soon nicknamed ‘Sabre Slayer’ and not without reason. Its performance in the air battles was so impressive that even the supersonic F-104s refused to engage it and almost invariably decided to break off combat by cutting in their afterburners, when chased by a Gnat.

Learning that daylight operations against Indian airfields were costly, the enemy started visiting these places at night with their Martin B-57 Canberras. But here again accurate antiaircraft fire usually made the Pakistani pilots drop their bombs in a hurry and scuttle away. While the fact was that the B-57 night raids failed to hit any worthwhile installation, Pakistan continued to churn out fantastic claims of aircraft destroyed and airfields put out of action. For example, after a night raid on Ambala the enemy claimed twenty-seven Indian aircraft destroyed on the ground, whereas in reality, except for a section of the old flying control tower, none of the airfield installations, let alone a single aircraft, had even been damaged. All the enemy bombs had fallen on non-military targets. Then again, the airfields at Pathankot, Adampur and Halwara were claimed to have been put out of action.

The Air Attachés of foreign countries who were taken round all the airfields in the Punjab after the cease-fire were able to see at first-hand that none of these airfields had been put out of commission or rendered inoperative for even a single day.

The destruction of MiGs was another fantastic claim, which was floated by the Pakistani propagandists. They claimed that the Pakistan Air Force had destroyed nine MiG-21s. In fact the IAF started the operations with only nine MiG-21s and was prepared to show eight of these aircraft at the end of the campaign. On the other hand, the destruction of seventy-three Pakistani aircraft in air battles and by ground fire has been conclusively corroborated by cine gun film records, supported by eye-witness accounts of pilots and recovery of wrecks on the ground.

After the first few skirmishes PAF efforts flagged and resistance to Indian daylight attacks declined. The last raid put in by the IAF, for example, with a section of Canberras on the vital radar installation at Badin in Sind, did not meet any aerial resistance at all, but only ack-ack - which did not, however, stop the Canberras from destroying this installation with rockets.

Ground personnel re-arm the 20mm cannon service on this PAF Sabre.

Mohammad Mahmood Alam was a scrap of a man who appeared almost lost in the none-too roomy cockpit of a Sabre. Yet on 7 September, this Pakistani squadron commander established a combat record which has few equals in the history of jet air warfare. Alam was born on 6 July 1935 to a well-educated family of Kolkata, British India. Although born and raised in the Bengal region, Alam was not ethnically Bengali, contrary to common perception. Alam’s family was of Urdu-speaking Bihari origin, having emigrated from Patna and settled in the Bengal province of British India for a long time. The family migrated from Calcutta to eastern Bengal which became East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) following the formation of Pakistan in 1947. Alam completed his secondary education in 1951 from Government High School, Dhaka in East Pakistan. He joined the then RPAF now PAF in 1952 and was granted commission on 2 October 1953.

Many pilots have scored several air victories in one sortie and have equalled or exceeded Alam’s claim of shooting down up to five enemy aircraft of superior performance within a few minutes. But few are likely to be able to match his record of destroying at least three opponents-Hunters of the Indian Air Force - within the space of somewhere around 30-40 seconds. Admittedly, confirmation of Alam’s claims had been difficult to obtain, despite close-range observations of this encounter by several PAF pilots and some gun camera evidence. Nearest of these observers was his wingman, Flying Officer Masood Akhtar, who, protecting his leader’s tail, clung like a leech throughout the action. Another section of PAF Sabres, led by Flight Lieutenant Bhatti, was attempting to engage the Hunters but Alam got there first. Flying top cover in an F-104 was Arif Iqbal who, with intense fascination and frustration watched the brief combat.

On this basis, Alam was originally credited with five IAF Hunters destroyed, although the wreckage of only two could be found in Pakistani territory, within two or three miles of Sangla Hill railway station. The bodies of the pilots - one Hindu and one Sikh - were reportedly burnt beyond recognition. The area of the main engagement however, thirty miles east of Sargodha airfield, was only about fifty-five miles inside the Pakistan border - seven or eight minutes at jet speed. Thus only the IAF is in a position to verify, some day, its actual losses on the second day of its war with Pakistan. The clear ascendancy established by the PAF pilots in this encounter and those that would follow on that fateful day was a powerful factor in heightening both morale and fighting spirit in Pakistan’s outnumbered but resolute air arm. Alam takes up his account of that engagement:

‘As we were vectored back towards Sargodha, Akhtar called, ‘Contact - four Hunters’ and I saw the IAF aircraft diving to attack our airfield. So I jettisoned my drops (underwing tanks which can be quickly released, for greater combat agility, before going into action) to dive through our own ack-ack after them. But in the meantime I saw two more Hunters about 1,000 feet to my rear, so I forgot the four in front and pulled up to go after the pair behind. The Hunters broke off their attempted attack on Sargodha and the rear pair turned into me. I was flying much faster than they were at this stage - I must have been doing about 500 knots - so I pulled up to avoid overshooting them and then reversed to close in as they flew back towards India.

‘I took the last man and dived behind him, getting very low in the process. The Hunter can outrun the Sabre - it’s only about fifty knots faster - but has a much better acceleration, so it can pull away very rapidly. Since I was diving, I was going still faster and as he was out of gun range, I fired the first of my two Sidewinder air to air missiles at him. In this case, we were too low and I saw the missile hit the ground short of its target. This area east of Sargodha, however, has lots of high tension wires, some of them as high as 100-150 feet and when I saw the two Hunters pull up to avoid one of these cables, I fired my second Sidewinder. The missile streaked ahead of me, but I didn’t see it strike. The next thing I remember was that I was overshooting one of the Hunters and when I looked behind, the cockpit canopy was missing and there was no pilot in the aircraft. He had obviously pulled up and ejected and then I saw him coming down by parachute. This pilot (Squadron Leader Onkar Nath Kakar, commander of an IAF Hunter squadron) was later taken prisoner.

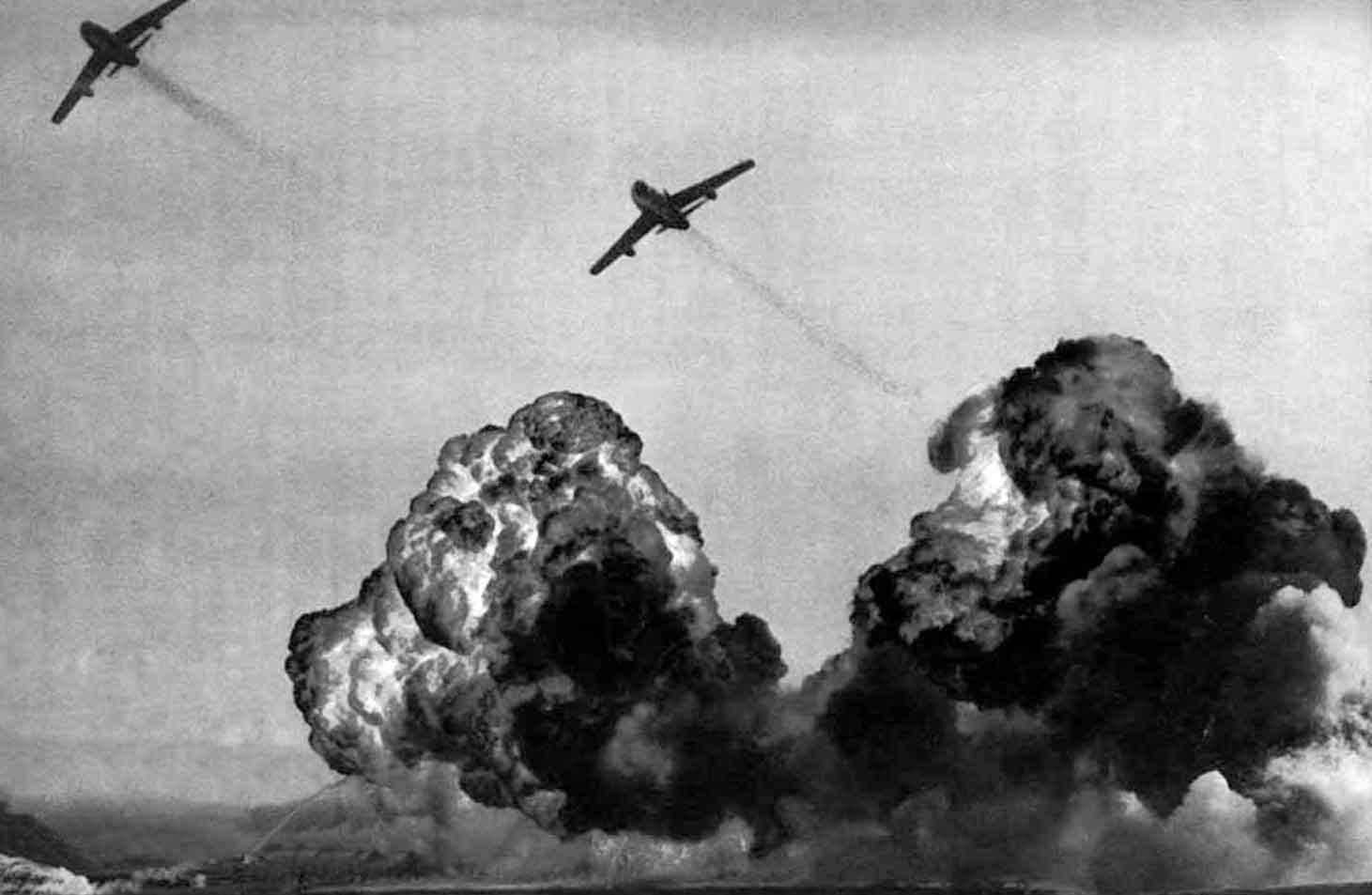

Napalm bombs dropped by two PAF F-86 Sabres exploding on target.

‘I had lost sight of the other five Hunters, but I pressed on thinking maybe they would slow down. (There were, of course, still only two Sabres pitted against the remaining five IAF aircraft). I had lots of fuel so I was prepared to fly 50-60 miles to catch up with them. We had just crossed the Chenab River when my wingman called out, ‘Contact Hunters 1 o’clock’ and I picked them up at the same time - five Hunters in absolutely immaculate battle formation. They were flying at about 100-200 feet, at around 480 knots and when I was in gunfire range they saw me. They all broke in one direction, climbing and turning steeply to the left, which put them in loose line astern. This, of course, was their big mistake. If you are bounced, which means a close range approach by an enemy fighter to within less than about 3,000 feet, the drill is to call a break. This is a panic manoeuvre to the limits of the aircraft’s performance, which splits the formation and both gets you out of the way of an attack and frees you to position yourself behind your opponent. But in the absence of one of the IAF sections initiating a break in the other direction to sandwich our attack, they all simply stayed in front of us.

‘It all happened very fast. We were all turning very tightly-in excess of 5g or just about on the limits of the Sabre’s very accurate A-4 radar ranging gunsight. And I think before we had completed more than about 270 degrees of the turn, at around twelve degrees per second, all four Hunters had been shot down. In each case, I got the pipper of my sight around the canopy of the Hunter for virtually a full deflection shot. Almost all our shooting throughout the war was at very high angles off - seldom less than about thirty degrees. Unlike some of the Korean combat films I had seen, nobody in our war was shot down flying straight and level. I developed a technique of firing very short bursts-around a half second or less. The first burst was almost a sighter, but with a fairly large bullet pattern from six machine guns, it almost invariably punctured the fuel tanks so that they streamed kerosene. During the battle on 7 September, as we went around in the turn, I could just see, in the light of the rising sun, the plumes of fuel gushing from the tanks after my hits. Another half second burst was then sufficient to set fire to the fuel and, as the Hunter became a ball of flame, I would quickly shift my aim forward to the next aircraft. The Sabre carried about 1,800 rounds of ammunition for its six 0.5 inch guns, which can therefore fire for about fifteen seconds. In air combat, this is a lifetime. Every fourth or fifth round is an armour piercing bullet and the rest are HEI - high explosive incendiary. I’m certain after this combat that I brought back more than half of my ammunition, although we didn’t have time to waste counting rounds.

‘My fifth victim of this sortie started spewing smoke and then rolled on to his back at about 1,000 feet. I thought he was going to do a barrel roll, which at low altitude is a very dangerous manoeuvre for the pursuer if the man in front knows what he’s doing. I went almost on my back and then realised I might not be able to stay with him so I took off bank and pushed the nose down. The next time I fired was at very close range-about 600 feet or so - and his aircraft virtually blew up in front of me.’ 33

According to Fizaya in Psyche of the Pakistan Air Force by Pushpindar Singh and Ravi Rikhye, ‘In the Pakistan-India conflict of 1965, the first 48 hours established the superiority of PAF over its much larger adversary. The major successes which contributed towards the PAF getting the better of IAF are its lightning action on the Grand Trunk Road by F-86s of 19 Squadron, when on 6 September the Indian Army was prevented from crossing the last defence before Lahore, the BRB Canal just in time as the lead brigade of Indian 15th Infantry Division was about to throw a bridgehead across the BRB Canal when it was attacked by the F-86s that strafed it and other elements of the Division up and down the Grand Trunk Road, throwing the Indians into confusion, delaying the advance and thus allowing Pakistan’s 10th Division to assume its forward positions, which ended the Indian hope of a quick victory.

‘The other missions which deserve special credit along with PAF’s successful defence of Sargodha on 7 September are the attacks on Kalaikunda, where 14 Squadron F-86s from Dhaka destroyed numerous Canberras lined up on the tarmac; 19 Squadron’s famous raid on Pathankot in which IAF MiG-21s, Gnats and Mystères were caught off guard on the ground; and 5 Squadron’s ill-fated strike over Halwara, which ended in tragedy but had far reaching consequences.

Having set off to a flying start by enabling the destruction of the Indian Vampires on 1 September, Squadron Leader Sarfraz Ahmed Rafiqui had set very high standards. On 6 September, when the Indian Army launched its three-pronged offensive, like the other squadrons at Sargodha, Rafiqui’s pilots too were kept busy in ground support sorties to stop the Indian onslaught. At 1300 hours, tasking orders were received for the implementation of the pre-designated strike plan. For a Time Over Target (TOT) of 1705 hours, Squadron Leaders Mohammad Mahmood Alam and Rafiqui were to attack Adampur and Halwara with F-86s from Sargodha while from Peshawar, Squadron Leader Sajad Haider’s squadron was to strike Pathankot with eight F-86s and two as armed escorts. Halwara was situated southwest of the industrial township of Ludhiana, Punjab, not far from the border and surrounded by numerous agricultural fields. At this airbase were Nos. 7 and 27 Hunter Squadrons. 7 Squadron had moved to Halwara from Ambala in August. The war was expected to come so from the second half of August Combat Air Patrols (CAP) were flown regularly.

All the three Pakistani F-86 squadrons got busy in preparing for the strikes. When Rafiqui learnt that only four Sabres would be available for the strike on Halwara, he detailed himself as Leader with Flight Lieutenant Cecil Chaudhry as No.2, his Flight Commander Flight Lieutenant Younus Hussain, Sitara-e-Jurat, another outstanding pilot as No.3 and Flight Lieutenant Saleem as No 4. Rafiqui reached the flight lines along with his pilots at 1600 hours to get airborne at 1615 for attacking Halwara at 1705 but to his surprise, he discovered that none of the allocated aircraft was ready. The morning’s defence of Lahore had taken its toll and there were minor unserviceabilities or the aircraft had landed late and were yet to be turned around. He informed the Station Commander of the delay and was advised to make good whatever TOT was possible. The same was the case with Mohammad Mahmood Alam as his aircraft were not ready on time either. Meanwhile, Squadron Leader Sajad Haider struck Pathankot exactly on time and achieving complete surprise, carried out textbook pattern attacks and devastated his target.

Squadron Leader Najeeb Khan, OC 7 Squadron during the 1965 war walks away from his B-57 after a sortie. He was leading a flight of two B-57 bombers to Ambala on the night of 18 September, one of the heavily defended air base of the Indian Air Force. (Air Commodore (Retd) Rais A Rafi).

Alam’s formation got ready before Rafiqui’s and he took off with Flight Lieutenants’ Syed Saad Akhtar Hatmi, Sitara-e-Jurat, Alauddin ‘Butch’ Ahmad34 and Murtaza to attack Adampur. As Rafiqui approached the aircraft to start up at 1715 hours, his heart was full of remorse. He was not concerned about himself but realizing the suicidal nature of his mission, he was thinking of Younus, who had been blessed with a second son the previous week but had not been able to go home to see him and Cecil Chaudhry who had recently been married. With grief in his eyes but determination on his face, Rafiqui tapped them on the shoulders and wishing them luck, climbed aboard his aircraft. During taxi, No 4’s generator packed up and Saleem was ordered by Rafiqui to abort the mission.

About the time of the attack on Pathankot, four Hunters of 7 Squadron were on patrol near Taran Taran. This formation code-named ‘Grey’ was led by the Squadron’s CO, Wing Commander A. T. R. H. Zachariah and consisted of Squadron Leaders A. K. Rawlley and M. M. Sinha and Flight Lieutenant S. K. Sharma. The patrol reached Taran Taran when they spotted some Sabres coming in at low level. The Sabres, led by Squadron Leader Mohammad Mahmood Alam, had been unable to reach Adampur as there was stiff opposition by the Indian Air Force, who were alerted by the raid on Pathankot. Down to only three aircraft, the formation had pressed on in the fading light. The Sabres on spotting the Hunters, shed their drop tanks and started gaining height, while the Hunters did the same. In the fight that followed, Rawlley was shot down and killed by Alam who then aborted the attack and extricated his aircraft from the fight. Alam’s Sabre formation exiting out of the area crossed the Sabre formation led by Squadron Leader Sarfraz Rafiqui. Alam had warned Rafiqui’s formation about the presence of the Hunters but Rafiqui carried on with his strike mission on Halwara airbase. The Hunters being low on fuel left the Sabres and started making it back to the base. Zachariah reported the loss of Rawlley and the two Hunters on the Operational Readiness Platform were ordered to take off.

Martin B-57B 33-941 call-sign ‘Zulu 6’ on 8 Squadron, 31 Bomber Wing based at Pakistan Air Force Station Mauripur (now Base Masroor) at Karachi, flown by 31 year old Squadron Leader Mohammad Shabbir Alam Siddiqui and the 32 year old navigator Squadron Leader Muhammad Aslam Qureshi which was shot down on the night of 6/7 September 1965.

That evening, two pairs of Hunter CAPs (Combat Air Patrols) were airborne, one from 7 Squadron with Flying Officers A. R. Gandhi and Prakash Sadashiv Rao Pingale35 and the other from 27 Squadron with Flight Lieutenant D. N. Rathore and Flying Officer V. K. Neb. Gandhi who joined 7 Squadron in May 1965 was flying his fourth sortie of the day and Pingale was on his first. The two Hunters took off for their CAP over Halwara. Ten minutes later Halwara Air Control informed them that they were under attack by F-86s. The Hunters arrived over the airfield and could not figure out anything in the confusion. The airfield’s ack-ack guns shot down one of the F-86s which dived headlong into the ground near the airfield. Rafiqui’s formation had reached Halwara at 1800 hours. By then visibility had reduced considerably and they were having difficulty in locating the target. As they were positioning themselves to execute the attack, they spotted the two Hunters being flown by Gandhi and Pingale in front of them, Chaudhry and Younus who were criss-crossing behind their leader to keep them clear of the enemy threat from the rear, saw the Hunters as soon as Rafiqui called contact with them. Rafiqui positioned himself behind them and called to Chaudhry to take the Hunter on the left while he would take the one on the right. Since Younus was in a better position and Chaudhry had lagged slightly behind, Younus suggested that the leader should take the one on the left and he could take the one on the right. Rafiqui agreed and while Chaudhry cleared the tails of both the Leader and No.3, Rafiqui’s guns found their mark before Younus could shoot. The first indication the Hunter pilots had that the Sabres had jumped them was when bullets fired out of nowhere slammed into Pingale’s Hunter. Pingale suffered systems failure and loss of engine power. He ejected from his stricken aircraft safely and was picked up later. Younus saw his target break viciously to the right. He followed him in the turn and just then two more Hunters appeared from the right. Both Chaudhry and Rafiqui spotted them and as Rafiqui manoeuvred to position himself for the kill, Chaudhry took up a defensive position behind him. Chaudhry was wondering why the leader hadn’t commenced firing, when Rafiqui’s calm and confident voice called out that his guns had jammed and Chaudhry should take over lead. At that time they were heading west and could have easily disengaged from the combat taking advantage of the fading light heading into the setting sun. This would have meant abandoning Younus, whom they had lost in the melee while he was chasing his target.

Squadron Leader Shabbir Alam Siddiqui, pilot of the Martin B-57 Canberra on the night of 6/7 September 1965 and Squadron Leader Aslam Qureshi, navigator who did not return from their third bombing mission when they were shot down shortly before dawn on 7 September after dropping two bombs on Jamnagar airfield. They were in the circuit to drop the remaining load when they were hit by AAA fire and crashed. Both crew died on impact and were buried in nearby fields.

Squadron Leader Aslam Qureshi, navigator of the Martin B-57 Canberra on the night of 6/7 September 1965.

Rafiqui attacked Gandhi’s aircraft and overshot him. Presented with a nice target, Gandhi manoeuvred behind it and started firing his cannon. Even though he did not take good aim, the 54 foot spread of the Hunter’s four 30 mm cannon shells took care of the Sabre. Gandhi could see the Sabre was streaming smoke and was at 150 feet, when the cockpit canopy flew off. The Pakistani pilot had pulled his ejection lever and before the ejection sequence began, the Sabre nose-dived into the ground and blew up. Flying Officer Gandhi had got the first kill for the ‘Battleaxes’. Before he could revel in his triumph, the remaining three Sabres made a beeline for his aircraft. His right wing got hit repeatedly. The Hunter lazily rolled to the right and entered into a spin. Gandhi ejected and landed on the outskirts of Halwara. Chaudhry overshot from the left, throttling forward. As he positioned himself behind the trailing Hunter, he saw the Hunter Leader pull away but by then he had opened fire and to his satisfaction he saw the enemy aircraft streaming smoke and the pilot eject. Chaudhry suddenly became aware of the eerie silence surrounding him. He looked around for his Leader and called him on the RT but received no response. The next instant he observed an F-86 in a classic scissors manoeuvre with a Hunter and thought it was Rafiqui but when he saw its guns blazing, he realized it must be Younus since Rafiqui’s guns had jammed. Before Younus could get his target, another Hunter pounced on him and Younus was shot down. Left alone and running short of fuel, Chaudhry bravely fought his way out and managed to reach base to narrate the details of the courage and determination displayed by Rafiqui and Younus.

Flying Officer Waleed Ehsanul Karim, Shaheed (Martyr) born July 1944, Harbang, Chakaria, Cox’s Bazar, British India in front of his F-86 54989, one of the youngest Sabre jet pilots in the world was killed on 19 April 1965 when his recently repaired aircraft (which was hit by anti-aircraft guns at Rann of Kutch in the morning sortie) developed engine trouble and plunged into the Arabian sea about 10-15 miles off the south coast of Karachi when he was returning from a reconnaissance mission over Gujarat.

The last two Sabres were continuing their strafing when the two Hunter F.56s, flown by Flight Lieutenant D. N. Rathore and Flying Officer V. K. Neb as No.2, returning from a sortie, were directed towards the Sabres at about 18.40 hours, when the sun had gone down and the horizon was lit only by twilight. Rathore, who was about three miles from Halwara airfield, caught a flash in the air in the vicinity of the base. A second look confirmed that the base was under attack by Pakistani Sabres and that a dogfight was in progress with another section of two Hunters led by Gandhi. Rathore, warning Neb, immediately turned towards the airfield. The remaining two Sabres were strafing the airfield and bombing it from a very low level. Jockeying for position was not difficult as the two Pakistani pilots were concentrating on their ground attacks. Getting behind the Sabre, which was on his right, Rathore closed in to 1,000 yards, at the same time instructing Neb to take on the Sabre on the left. Overtaking his victim fast, Rathore closed in to 650 yards before opening fire. He saw the hits, registering on the Pakistani Sabre and it abandoned its ground attack. Closing in still further, Rathore fired again, from 500 yards. This time the Sabre was mortally hit. It started banking to the left and then turned into the ground, exploding in a huge sheet of flame five or six miles away from the airfield. Meanwhile, Neb had closed in behind the second Pakistani Sabre which, like the first one, was intent on strafing the airfield below. Neb, incidentally, had not carried out any air-to-air firing before and at the time of this engagement was still under operational training. Aiming and firing he lost no time closing in on the Pakistani Sabre to about 400 yards. The Pakistani pilot at once abandoned his attack on the airfield and pulled up sharply. Neb, unsure of his accuracy because of lack of any practice, rapidly closed in to less than 100 yards and fired again on the sharply climbing Sabre, which presented a much better target this time. He saw pieces fly off the Sabre, as his cannon shells found their mark and shredded the Sabre’s left wing in an instant. There was a puff of smoke which rapidly turned into a sheet of flame as the last of the four Pakistani Sabres disintegrated in mid-air and fell to the ground. Both the Hunters formed up and flew back to base.

It has been said that it was difficult to assess how many Indian aircraft were in the air to defend Halwara when Rafiqui’s strike formation arrived and that ‘it is beyond comprehension that after being alerted by the successful PAF attack with ten F-86s on IAF Base at Pathankot they would have only two in the air and later divert two more.’ Sarfraz Rafiqui’s determination to lead the attack on Halwara, deep inside enemy territory, being heavily outnumbered and having lost the element of surprise, speaks volumes for his sense of duty and courage. Although he would have been perfectly justified to leave the battle area, his decision to continue the engagement with the enemy despite his guns being jammed is in the highest traditions of chivalry. For him the end was never in doubt.36

Sarfraz Rafiquis’ parents’ grief over the earlier loss of their elder son Ijaz in a Hawker Fury crash many years ago had not quite subsided when a poignant message addressed to Mr. B. A. Rafiqui arrived by telegram at 22 ILACO House, Victoria Road, Karachi. It read, Regret to inform, your son Squadron Leader Sarfaraz Rafiqui failed to return from a mission against enemy…Any further news about him will be conveyed immediately. Letter follows. His fate was officially known only after the war when, dreadfully, he was not amongst the PoWs being exchanged.

On 8 September four IAF Hunter pilots were briefed to carry out an offensive sweep over the Raiwind-Khem Karan sector. Composition of the formation was: Flight Lieutenant C. K. K. Menon, leader; Flight Lieutenant A. S. Kullar, No. 2; Flight Lieutenant D. S. Nagi, No. 3 and subsection leader; and Squadron Leader. B. K. Bishnoi, No. 4. The planes were armed with rockets and 30mm cannon. The section of four took off at 1800 hours for the target area. The aircraft kept low, flying between fifty and one hundred feet above the ground, the fertile green countryside of the Punjab passing under their wings as a blur. As the section approached Raiwind railway station, all four pilots saw a goods train which had pulled in. Menon decided that it was carrying military stores because the locomotive was attached to that end of the train which pointed towards Kasur, in the battle area. Simultaneously the layout of the station and the area around the train was firmly implanted in his memory. All this had to be assimilated in about a second as the aircraft swept past.

A formation of IAF Hawker Hunter F.Mk.56s BA360A and A489 on patrol over Ladakh.

Menon as the leader asked his pilots whether they should take on the train. The reply was a unanimous affirmative. As the section had passed over the station, anti aircraft guns had opened up. To confuse the Pakistani gunners and also to utilise the section of Hunters to the best effect against the train, Menon decided to approach the goods train from a different direction. He therefore led the section well past the railway station till he was quite certain that the aircraft would be out of sight of those watching from the station. He then put his section in a wide left-hand turn. This ruse was to give the impression that the Hunters had missed seeing the goods train. The wide turn also enabled him to place his pilots in the best position for attack.

Coming out of the turn, Menon led his section on a course parallel to the length of the train, but still low. Judging the section’s position to be abreast of the goods train, Menon pulled up his aircraft signalling the start of the attack. Almost simultaneously the other three Hunters pulled up. At the same time, the Pakistani anti-aircraft guns, sighting the Hunters, opened up again. At the top of their climb the aircraft were in their most vulnerable position, their speed having fallen off, before diving for their rocket attack. The positioning of the section by Menon had been excellent. As they pulled up and rolled to the left in the attacking dive, the section faced the train broadside and was evenly spaced out along the entire length of the target. Going in first, through the mushrooming flak, Menon concentrated on the extreme left of the train. He released his rockets at about 500 feet and levelling out from the dive a bare 100 feet above the ground he flashed over the train. He could not see his rockets hit the target. But Bishnoi, who as No. 4 was the last to go in, could see clearly the effect of the other three pilots’ strikes. Bishnoi saw Menon’s rockets strike the wagons on the extreme left. The explosion lifted them off the rails and set fire to them.

Kullar attacked the middle left of the target and Bishnoi saw his rockets also hit their mark and turn that section of the train into a blazing inferno. As Kullar hurtled low, over the train with ack-ack puffs chasing him, Nagi’s rockets hit home in the middle right of the goods train. A powerful explosion ripped through the wagons, although as in all rocket attacks Nagi was not able to see the result of his attack. Bishnoi however, being the last in, saw Nagi’s rockets hit home. Putting the extreme right end of the train in his sights, Bishnoi then fired his own rockets from about 400 feet. He watched their smoke trails heading towards the target, but then he too was very low and had to level out of the dive. He went over the train at about 100 feet and then turned to see the effect of his attack. Bishnoi’s rockets had also found their mark and the wagons at the extreme right were also burning furiously.

By now explosions had started ripping the train apart and the whole area was enveloped in smoke and flames. Bishnoi called up his leader, Menon, on the R/T who also turned to see the success of their attack. Kullar and Nagi too had a glance at the now completely destroyed goods train and then the section turned to fly up the railway line from Raiwind towards Kasur. Menon and Kullar still had some rockets left and all four had their front-gun ammunition intact.

Nearing Kasur the pilots noticed a huge cloud of dust slightly to one side, so Menon led his section, flying very low, in that direction. Menon and Kullar picked up two groups of tanks as their target and pulled up to attack them. As their aircraft gained height rapidly, a murderous fire opened up on them from the ground. Undeterred, Menon went into a dive, latching on to one group of tanks and fired his remaining rockets. Three tanks burst into flames. Kullar who had followed Menon in the attack concentrated on the second group of tanks and fired. He could not confirm the damage caused by his rockets but was certain that he had damaged a few. While Menon and Kullar were attacking the tanks, Nagi and Bishnoi, who had expended all their rockets in the train attack, took on some armoured vehicles with their cannon. Despite the very heavy ack-ack fire, they made two passes each at the armoured vehicles and saw a considerable number catch fire and blow up.

All this while the four aircraft were being subjected to very heavy ground fire. Not only were the regular ack-ack guns firing, but also the anti-aircraft guns mounted on Pakistani tanks and other automatic weapons were blazing away at the Hunters. Nevertheless, Menon, after attacking the tanks, spotted two convoys of vehicles. Pulling up, he engaged the nearest with his cannon. Then, pulling up again, he attacked the second convoy. In these two attacks, he saw that he had set fire to thirty vehicles which, with their inflammable stores, were now bursting and exploding. Kullar, the No. 2, after his rocket attack on the second group of tanks, pulled up again in the teeth of heavy ack-ack fire, ranged another tank in his gunsight and went for it with his cannon. He managed to disable it.

With their ammunition almost expended, the section turned back to base at very low level, re-forming at the same time. Assessing the damage to their own aircraft, Menon found that his fuel state was lower than it should have been; ack-ack had punctured his port wing tank and the fuel had leaked out. Another bullet had damaged his airspeed indicator. Kullar had been slightly more unlucky, a bullet had found his main fuel tank and punctured it, so his reaching the base was a touch-and-go affair. However, all four pilots reached base safely, although Menon had to be shepherded in because of his unserviceable ASI.

F-86 Sabre and B-57 bombers of the Pakistan Air Force.

He had gathered an impressive tally of one-quarter goods train destroyed, three tanks destroyed and thirty vehicles set on fire - all in about half an hour. How important that goods train was to the Pakistanis only came to light later. The train was carrying petrol and ammunition for the Pakistani tanks in the Khem Karan area and the enemy armour was depending for replenishment on this train. With its destruction, the Pattons in the Khem Karan sector were forced to go into battle with only thirty shells each and a limited amount of petrol. When their initial thrust was stopped by Indian armour, the Pakistani tanks had to withdraw, suffering heavy losses, because they did not have the fuel or ammunition to continue the fight.

On the morning of 9 September the Pakistanis were building up for an armoured thrust in the Khem Karan area and Indian troops were under great pressure. To relieve this pressure IAF Hunters had been called upon for ground strikes against Pakistani gun and armoured positions; two sorties had already gone out for this purpose.

For the third strike of the day, four pilots had been briefed. The section was to be led by Squadron Leader. B. K. Bishnoi, who only the previous evening had taken a hand in destroying the goods train at Raiwind station. The other pilots assigned were Flight Lieutenant G. S. Ahuja as No. 2, Flight Lieutenant S. K. Sharma as No. 3 and sub-section leader and Flying Officer Parulkar as No. 4. During the briefing these pilots were told to attack enemy tanks, armoured vehicles and gun positions in the Khem Karan area.

The take-off in sections of two was smooth. Bishnoi and Ahuja pulled up sharply after getting airborne to enable Sharma and Parulkar to avoid the jet blast on their take-off run. Settling down at about one hundred feet above ground, in tactical formation, they proceeded towards their target. Ahuja was on Bishnoi’s left and slightly behind him, while Sharma and Parulkar came up on their leader’s right about 500 yards away and slightly behind. This loose formation enabled everyone to concentrate on accurate low-level flying, navigation and at the same time keep a look-out for enemy aircraft and ground targets.

As the section approached the target area, still maintaining 100 feet above ground, Bishnoi spotted well to his left the tell-tale cloud of dust which indicated tank and vehicle movement. Bishnoi warned the others in the section that they were approaching enemy armoured concentrations and that everyone should choose his target. Ahuja, Sharma and Parulkar acknowledged the transmission. All four pilots switched on the electrical circuits for releasing their rockets and tested their front guns by firing a short burst. Bishnoi from his previous day’s experience over the same area was expecting enemy anti-aircraft fire - but not the kind of concentration that opened up as the four Hunters approached the tanks. The familiar black puffs of 40-mm. ack-ack almost blackened the sky around them and the Patton-tank-mounted guns sprayed the airspace with their lethal loads. There was one favourable factor, however. The 40-mm shells were bursting above the Hunters. The enemy gunners had not got the correct height, but then they were anticipating the pilots’ next move. The aircraft would have to pull up for a rocket attack and that would take them to a height where the sky was already pock-marked by ack-ack puffs. There was such a concentration of tanks, armoured cars and other vehicles that choosing targets was not difficult. Bishnoi selected a group of three tanks which were in a ‘U’ formation a little to his left. He pulled up to 300 feet and rolled into his attacking dive. Now the ack-ack fire seemed to be all round him and at the same height. Ignoring this Bishnoi settled his gunsight on this group of three tanks and then from about 400 yards distance, fired a salvo of eight rockets. Levelling out at about 50 feet he hurtled over the tanks and then turned to have a look. All three tanks had been hit and had blown up; they were burning furiously.

Following their leader’s example, the other three, Ahuja, Sharma and Parulkar, also selected tanks as their targets and pulling up, one by one, in the deadly danger zone of exploding anti-aircraft shells, delivered their rocket attacks. Between the three of them, they hit and destroyed seven more tanks. Having expended their rockets, all four Hunter pilots now decided to take on the armoured cars and other vehicles with their nose-mounted cannon.

After attacking the tanks Bishnoi had spotted a group of vehicles, to which he now turned his attention. Leaving the safety of low altitude, he pulled up again before engaging his new target. With heavy ack-ack fire following him, Bishnoi rolled into his attack from the apex of his pull-up and fired his cannon. He saw his shells hit and explode on the vehicles; in an instant the vehicles were on fire and the ammunition in them started exploding. By this time, however, Bishnoi had levelled out and, hugging the ground, had sped past the target. Ahuja in the meantime engaged some armoured cars with his cannon, while Sharma and Parulkar took on some more vehicles carrying supplies. Again and again pulling up in the face of murderous flak, all four went in for their strafing attacks until their ammunition was exhausted. After their last attack, the section remained low and sped out of the enemy area. Once out of range of the enemy ack-ack, the Hunters formed up again in tactical formation and set course for base.

Mohammed Shaukat-ul-Islam of the Pakistan Air Force. (Group Captain Mohammed Shaukat-ul-Islam)

Just as they were clear of the target area, Parulkar called up his leader, Bishnoi and told him that he had been hit in his right arm. Bishnoi was really concerned because, although Parulkar could probably manage to fly with his left hand till they reached their base, on landing he would need both hands and especially the right for coaxing the fighter down on to the runway. Throughout the flight back to base, Parulkar, who incidentally was on his first operational sortie, kept on assuring Bishnoi that he was all right. The section reached their base and immediately the first three landed.

All were now waiting for Parulkar. He made a normal turn on to the final approach and started coming lower and lower. With a sigh of relief, everyone saw him make a perfect touch-down and hurtle down the runway on his landing run. If his right hand was badly hurt, his troubles were not yet over. He would have to apply the brakes with his right hand to stop the aircraft. This too, Parulkar managed and, ignoring the ambulance and crash tender, turned on to the taxi track and taxied back to dispersal. It was only when he got out of the aircraft that his fellow pilots and his ground crew saw the seriousness of his wound. A bullet had hit his right upper arm and torn through the flesh, baring the bone. His overall was drenched with blood. He must have been in extreme pain and it was a wonder that he had not fainted due to lack of blood. Parulkar was of course rushed to hospital where the doctors put in nine stitches to close the wound. But such was his excitement that he was soon in the crew room recounting the day’s adventure to his squadron mates.

Muhammad Mahmood Alam (known as M.M. Alam), a F-86 Sabre flying ace and one-star general who served in the PAF, commanding 11 Squadron and was awarded the Sitara-e-Jurat (‘The Star of Courage’) for his actions during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. Alam holds the record of having downed five Indian aircraft in less than a minute.

Low-level dogfights in the modern jet age are said to be impossible - or at least improbable. But in the heat of battle even the improbable comes to pass. Such was the case on 19 September when an air battle was fought over the Chawinda Sector between Indian Gnats and Pakistani Sabres which started at about 1,500 feet and ended at tree-top height. Squadron Leader Denzil Keelor, born 7 December 1933 and his section of four Gnat aircraft was detailed to provide cover to four IAF Mystère IVAs which were going out for a close-support sortie to Chawinda. With Keelor were Flying Officer Rai his No. 2, Flight Lieutenant V. Kapila as sub-section leader and Flight Lieutenant Maya Dev as the No. 4. Taking off in their Gnats, they followed the Mystères at low level towards Chawinda. As they arrived over the target the enemy flak opened up and being very low, they could see the flak bursts near and above them. Suddenly Maya Dev called out a warning that four Pakistani Sabres were approaching to attack the Mystères. The four Gnat pilots spotted the Sabres on their left above them at about 4,000 feet. Denzil Keelor and his pilots were a bare 300 feet above the ground. He put his section into a shallow left-hand climbing turn so as to place himself behind the Sabres. As the distance between the two formations closed rapidly, Keelor saw that Kapila, with Maya Dev looking after his tail, was in the best position for an attack on the Pakistanis. He ordered Kapila to engage the nearest Sabre. As Kapila with commendable adroitness latched on behind one of them, the Pakistani became aware of this threat and started taking violent evasive action. He went into a hard turn to the left and Kapila followed him, but still could not get into a favourable firing position. Suddenly the Sabre reversed his turn and went into a steep turn to the right. This was the opportunity Kapila was waiting for. Jettisoning his drop tanks, he easily slipped into a firing position and, reducing the distance to 500 yards, gave a short burst, which at once went home.

The engagement which had started at about 1,500 feet was now getting lower and lower as the Sabre, in order to get away, was executing descending turns. With Kapila’s first burst striking the Sabre, it slowed down a bit. Getting nearer still, Kapila fired again from 300 yards. Again his shells found their mark. But by now being a bare 300 feet above the ground, he had to pull up; he did not see the Sabre spin and crash to the ground. But Keelor with Rai - who had been following Kapila and Maya Dev through this engagement to guard them against possible rear attacks - watched the end of the Sabre, which after Kapila’s second burst spun and hit the ground, exploding on impact. Keelor called out to Kapila confirming his kill. Just as Keelor had finished transmitting to Kapila he saw a Sabre which had been separated from his section in the melee, trying to get away from the scene. The Sabre apparently had not seen Keelor, as it did a hard turn to the right. This was a manoeuvre which gave Keelor the opportunity of quickly slipping behind the Sabre in a favourable firing position. Reducing the distance to less than 500 yards, Keelor fired a couple of bursts which were enough to send the Sabre crashing to the ground. It was only when the Sabre hit the ground that Keelor realised that he himself was skimming the tree tops. 37

India’s decision to open up the theatre of attack into Pakistani Punjab forced the Pakistani army to relocate troops engaged in the operation to defend Punjab. The war saw aircraft of the Indian Air Force (IAF) and the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) engaging in combat for the first time since independence. The IAF was flying large numbers of Hawker Hunter, Indian-manufactured Folland Gnats, de Havilland Vampires, English Electric Canberra bombers and a squadron of MiG-21s.

Pakistan used the F-104As primarily for combat air patrols, usually consisting of two Sidewinder-equipped F-86F Sabres, with a Starfighter to provide top cover. The F-104s occasionally provided escort to PAF Martin B-57B Canberra bombers or reconnaissance aircraft and sometimes flew high-speed photoreconnaissance missions themselves. No other aircraft in the history of aviation has engendered more controversy such notoriety and suffered such a high loss rate over a short period as the Starfighter. Pakistan, which remained an important ally of the United States through the Cold War, was the first non-NATO country to equip with the Starfighter. By September 1965 the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) had only 150 aircraft (including 102 F-86Fs), while the Indian Air Force (IAF) possessed approximately 900 aircraft. Twelve of the aircraft in the PAF inventory were Starfighters, the bulk of which were received in August 1961. These consisted of ten refurbished F-104As and two F-104Bs, all supplied under the US Military Defense Assistance Programme (MAP). At PAF’s request, all its F-104s were refitted with the M-61 gun, whereas the USAF had removed the weapon on the assumption that air combat after Korea would occur at high speeds where only AAMs would be effective. This and the more advanced GE-J-79-II engine made the PAF F-104s unique - they had the gun and being the lightest of the F-104 series therefore enjoyed the best thrust-to-weight ratio. All were used to equip 9 Air Superiority Squadron. This became an elite unit, its personnel handpicked from F-86 Sabre squadrons. The PAF Starfighters, which were each armed with two AIM-9B Sidewinder AAMs, were the first Mach 2 capable aircraft in Asia. Even in Europe at this time, most countries were still flying subsonic aircraft. Even before its introduction to combat, the Starfighter had gained such a reputation in the IAF that it was known as the ‘hadmash’, ‘scoundrel’ or ‘wicked one.

Many questioned Pakistan’s ability to fly and maintain such a sophisticated aircraft as the F-104A/B. (The in-commission rate of the F-104 during the first five years of service was over 80 per cent and all systems performed with high reliability). 9 Squadron lost only one Starfighter during training, when Flight Lieutenant Asghar ‘pitched up’ and went into an uncontrollable spin during an air combat training sortie. This F-104A was replaced under the MAP programme. Also, Flight Lieutenant Khalid managed a ‘dead stick’ landing after an engine flame out in another F-104A. PAF Starfighters were used throughout the wars with India in 1965 and in 1971.

During the 1965 conflict the PAF was out-numbered by around 5:1. The PAF’s aircraft were largely of American origin, whereas the IAF flew an assortment of British and Soviet aeroplanes. It has been widely reported that the PAF’s American aircraft were superior to those of the IAF, but according to some experts this is untrue because the IAF’s MiG-21, and Hawker Hunter fighters actually had higher performance than their PAF counterpart, the F-86 Sabre. Although the IAF’s de Havilland Vampire fighter-bombers were outdated in comparison to the F-86 Sabre, the Hawker Hunter fighters were superior in both power and speed to the F-86 according to Air Commodore Sajjad Haider, who led the PAF’s 19 Squadron in combat during the war.

Group Captain Zafar Masud the PAF station commander at Sargodha debriefing some of the pilots of 32 Wing.

Group Captain Mohammed Shaukat-Ul Islam recalls: ‘In November 1964 I was posted to 11 (F) Squadron, commanded by Squadron Leader Mohammad Mahmood Alam at Sargodha. I became operational in August 1965 and was allowed to take part in the 6-23 September 1965 war with India. I considered myself very lucky to have taken part in the war as a Flying Officer with only about eighty hours on the F-86F with a grand total of about 400 hours. At the outbreak of the war 11 Squadron was tasked to carry out a dawn strike against the Indian Army in Chamb-Jurian sector with two formations of eight F-86 aircraft. Each aircraft carried 32 x 5.75-inch rockets and 1,800 x .50 inch ammunition. We exhausted all the weapons on the convoy of the Indian army and returned to Sargodha safely. As it was a surprise dawn strike we faced only small arms fire from the enemy. By the time I landed and cleared the runway my aircraft flamed out because of shortage of fuel.

‘On 9 September four F-86Fs were tasked to provide a low level escort mission for three B-57 bombers attacking a train carrying ammunition at Gadro. The bombers carried out four attacks each and all seven aircraft remained within heavy ack-ack fire for about fifteen minutes. All aircraft exited low level after the successful delivery of weapons. The three bombers recovered at Peshawar and we four fighters came back to Sargodha safe and sound. It was my first experience of remaining within such heavy anti-aircraft fire for such a long time.

‘On 11 September, I was in a formation of four F-86Fs who took part in an escort mission at day time to give air protection to a train carrying ammunitions from Lahore to Sialkot sector. It might sound very easy but to give protection to such a slow moving train by so fast moving aircraft at low level by four aircraft for such a long time was very demanding. The train reached its destination and got its cargo off-loaded.’

On the night of 13/14 September Squadron Leader Mervyn Leslie Middlecoat achieved the first blind night interception in an F-104, firing a Sidewinder at a Canberra from a distance of 4,000 feet and reporting an explosion, but failing to obtain a confirmation. Another Starfighter was lost on 17 September, when Flying Officer G. O. Abassi tried to land in a sudden dust storm, undershot the runway and crashed in a ball of fire. Miraculously, he was thrown clear, still strapped in his ejection seat and he survived with only minor injuries.

On 16 September Group Captain Mohammed Shaukat-Ul Islam took off from Sargodha as Squadron Leader Mohammad Mahmood Alam’s wingman to carry out a high level offensive patrol mission deep inside Indian territory.

‘We were flying in battle formation at 23,000 feet between two Indian Air Bases, Halwara and Adampur. The aim was to invite the Indian fighters to come and fight with us. We could take such a venture because by then the PAF already had established air-superiority over the IAF. It was about 2 pm with clear blue sky when our ground controller from a radar station transmitted that two IAF Hunters had taken off from Halwara and were approaching to intercept us. When they came in sight we jettisoned our drop tanks and entered into close air combat. The air battle became intense and under such high ‘g’ manoeuvres I could not stay on the tail of my leader. As it turned out, my leader shot the No.2 of the other formation and their leader shot me. My aircraft caught fire and I ejected through the shattered canopy at about 12,000 feet. I lost consciousness for a couple of seconds and by the time I got my senses back I was floating in the air and that the small parachute was pulling out the bigger one. As I settled down with my parachute I saw a Hunter with streaming fuel and crash with a big explosion. The Hunter pilot was shot in the cockpit. When I looked down to locate my probable landing spot, I noticed with horror that a man in uniform was pointing a .303 rifle at me and a civilian was aiming a double barrel shot gun. I heard three shots and within seconds my feet touched the ground. I got up, released the parachute and was surrounded by a crowd of people. The name of the place was Taran Taran. The local police rescued me from the crowd and took me quickly to a nearby police station and then to a hospital. I was bleeding profusely from my back. A doctor operated on me and showed me a .303 bullet taken out of my back. Next day I was taken to IAF Base, Adampur and flown to Delhi in an Antonov An-32 and admitted to the Combined Military Hospital (CMH). The cease-fire was declared on 23 September when I was still in the CMH. Later, I joined another pilot and a navigator of the B-57, which was shot down by AA fire on 15 September in a night raid over IAF Base Adampur. We three returned to Pakistan after being released in a prisoner exchange in February 1966.