Carrier-borne Combat Viêtnam 1964-1973

Air-to-air warfare in Southeast Asia began on 3 April 1965 when a US Navy strike force of four F-8Es bombing the Thanh Hóa Bridge was attacked by MiG-17s. One Navy aircraft was damaged during the engagement. Until 17 June, on which day a US flight of F-4Bs downed two MiG-17s with Sparrow missiles, aerial engagements had been infrequent. By mid-1965 the air-to-air contest was well inderway. The aerial battles in Viêtnam bore little resemblance to the dogfights of World War II or even Korea. The equipment had become so sophisticated and the speed of aircraft so significantly increased that it took coordination and teamwork to kill a MiG. Every air-to-air encounter involved the ability and training of many people - support personnel, ground crews, strike and protective flight air crews and the airborne and ground-radar operators. Unlike the air-to-air engagements of previous wars, in which a single pilot pitted his aircraft against a single opponent, some modern aircraft required two-man crews, working as an integrated and well-disciplined team.

RF-8G Crusader of VFP-63 ‘Eyes of the Fleet’ is catapulted off the flight deck of the USS Kitty Hawk, which was deployed to SE Asia in September 1963. The RF-8A of Lieutenant Charles ‘Chuck’ F. Klusmann of VFP-63 (PoW-escaped) was the first jet shot down and ejection of the air war in SE Asia, on 6 June 1964. F-8Es of VF-211 ‘Fighting Checkmates’ from the USS Hancock were the first to tangle with NVAF MiG-17s, on 3 April 1965, when eight MiG-17PFs of the 921st ‘Sao Đỏ’ (Red Star) Fighter Regiment from Nội Bài northwest of Hànôi attacked a USN strike force attacking bridges at Hàm Rồng. The gun camera in the lead MiG, piloted by 31-year old Captain (later General) Phạm Ngọc Lan, revealed that his cannons had set an F-8 ablaze, but Lieutenant Commander Spence Thomas landed his damaged Crusader at Đà Nẵng; the remaining F-8Es returning safely to their carrier. Lan had to break off low on fuel and he crash landed on the banks of the Đuống River.

F-4B-19-MC Phantom BuNo 151485 of VF-21 ‘Free Lancers’ dropping Mk 82 Snakeye bombs over Việtnam. VF-21 was assigned to Carrier Air Wing 2 (CVW-2) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Midway (CVA-41) for a deployment to Việtnam from 6 March to 23 November 1965. During a combat air patrol on 7 May 1968 this aircraft, now with VF-92 on the Enterprise, was part of a section of five F-4Bs led by Lieutenant Commander Ejnar S. Christensen that became engaged in a running fight with several MiGs of the VPAF 921st Regiment north of Vinh. BuNo 151485 was shot down by Nguyen Van Coc for his seventh aerial victory after he fired two R-3S Atoll missiles from an altitude of 4,900 feet. The F-4B burst into flames and crashed into the sea. Christenson and his Radar Intercept Officer, Lieutenant (jg) Worth A. Kramer ejected safely from their aircraft before impact and were recovered a short time later.

The Korean War had shaken the military might of America and it led to far-reaching changes in the equipment it would need to fight any similar war anywhere in the world. The Navy replaced its F9F Panther and F2H Banshee straight-winged jets with the F-4 Phantom and the Vought F-8 Crusader became the standard carrier-based fighter, although propeller-driven aircraft, like the Douglas A-1 Skyraider,56 still had a role to play. Ed Heinmann’s Douglas A-4 Skyhawk was designed to replace the Skyraider and fulfill a multiplicity of roles for the Navy, including interceptor and nuclear weapons carrier, but for a while both aircraft served alongside each other when war broke out in South-East Asia. The Republic of South Viêtnam was created in July 1954 using the 17th Parallel to separate it from the Communist North. However, Hồ Chi Minh’s Viêt Minh forces, led by General Võ Nguyên Giáp, planned to take over control of the South using a new Communist guerrilla force called the Viêt Công (VC) or National Liberation Front (NLF). The VC campaign increased in intensity in 1957 and finally, in 1960, Premier Ngo Dinh Diem appealed to the United States for help. In 1961 ‘special advisers’ were sent in and later President Lyndon B. Johnson began the first moves, which would lead to total American involvement in Viêtnam.

When, in 1964, two Crusaders were brought down during a reconnaissance mission over Laos, the USAF flew a retaliatory strike on 9 June against AAA sites. On 2 August, against the background of open warfare in Laos, and increasing infiltration across the North/South Viêtnamese border, North Viêtnamese torpedo boats attacked the destroyer USS Maddox in international waters in the Gulf of Tonkin. The destroyer was cruising along a patrol line in the northern region of the Gulf in order to gather intelligence as part of Operation ‘Plan 34A’. This was a covert campaign that started in February 1964 and it was intended to deter the North Viêtnamese from infiltrating the South. One of the torpedo boats that attacked the Maddox was sunk by a flight of four F-8E Crusaders led by 40-year old Commander James Bond Stockdale of VF-53 from the Ticonderoga, who made several strafing runs on the boats, firing their 20mm cannon and Zuni unguided rockets.57

During the night of 4/5 August Maddox, now reinforced by USS Turner Joy, returned to its station off the North Viêtnamese coast to listen for radio traffic and monitor communist naval activity. Shortly after a covert South Viêtnamese attack on a coastal radar station near Cua Rim, the two destroyers tracked on radar what they took to be enemy torpedo boats. Debate still rages whether there really was any North Viêtnamese boats in the vicinity of the two destroyers. Apparently no attack developed and no boats were seen by the pilots of the aircraft launched to provide air cover. However, the incident was enough to force President Johnson into ordering Operation ‘Pierce Arrow’, a limited retaliatory raid on military facilities in North Viêtnam. On 10 August the US Congress passed what came to be known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution which was as close as the US ever came to declaring war on North Viêtnam but which actually fell far short of that. The Gulf of Tonkin Incident also resulted in a major increase in US air strength in the Southeast Asia theatre and saw US involvement change from an advisory role to a more operational role, even though US aircraft and airmen had been participating in operations ever since they first arrived in the region.

A-4C 149574 of VA-153 ‘The Blue Tailed Flies’ is launched from the deck of the USS Coral Sea off Viêtnam in 1965. On 25 June this Skyhawk and Commander Peter Mongilardi, CAG, Carrier Air Wing 15 was leading two other Skyhawks on an armed reconnaissance mission when he spotted a small bridge over the Sông Cho River about 10 miles northwest of Thanh Hóa. As the formation rolled into the attack, Mongilardi’s aircraft was struck by 37mm flak. The first CAG to be lost in the war, he had been lucky to survive damage to his Skyhawk during the 29 March raid on Bạch Long Vĩ when he had to be ‘towed’ back to the carrier by a tanker as his aircraft was leaking fuel almost as fast as it was receiving it.

On 17 June 1965 two VF-21 ‘Freelancers’ F-4Bs from the USS Midway (CVA-41) scored the first MiG kills of the war when they attacked four MiG-17s south of Hànôi and brought down two with AIM-7 Sparrow missiles. L-R: Commander Louis C. Page; Lieutenant John C. Smith; Lieutenant Jack E. D. Batson, Page’s Radar Intercept Officer; and Lieutenant Commander Robert B. Doremus, Smith’s RIO.

On 24 August 1965 on a mission to hit the ‘Dragon’s Jaw’ Bridge at Thanh Hòa Lieutenant Commander Robert B. Doremus (pictured after his release on 2 February 1973) and Commander Fred Augustus Franke, commander of VF-21 were shot down in their F-4B and were held prisoner for 7½ years in Hànôi.

The political and physical restrictions on the basing of us aircraft in South Viêtnam was to some extent solved by the permanent stationing of aircraft carriers in the South China Sea. By the end of August four aircraft carriers, the Bon Homme Richard (CVA-31), Constellation, Kearsarge and Ticonderoga had arrived in position in the Gulf and started a pattern of line duty that continued until August 1973. The carriers and their protecting forces constituted the US 7th Fleet’s Task Force 77, which in March 1965 developed a pattern of positioning carriers at Yankee Station in the South China Sea off Đà Nẵng from which to launch attacks against North Viêtnam. On 20 May TF 77 established Dixie Station 100 miles southeast of Cam Ranh Bay from where close air support missions could be mounted against South Viêtnam. The carriers developed a system that normally kept each ship on line duty for a period of between twenty-five and thirty-five days after which the carrier would visit a port in the Philippines, Japan or Hong Kong for rest and replenishment of supplies. Each carrier would normally complete four spells of duty on the line before returning to its homeport for refitting and re-equipping. However, the period spent on line duty could vary considerably and some ships spent well over the average number of days on duty. The establishment of Dixie Station required the assignment of a fifth carrier to the Western Pacific to maintain the constant presence of at least two carriers at Yankee Station and one at Dixie Station. By the summer of 1966 there were enough aircraft based in South Viêtnam to provide the required airpower and Dixie Station was discontinued from 4 August.

Operation ‘Pierce Arrow’ began in the early afternoon of 5 August with twenty aircraft from Constellation (ten A-1H Skyraiders, eight Skyhawks and two F-4 Phantoms) attacking the torpedo boat base near the coal-mining town of Hon Gai northeast of Hànôi while twelve more (five Skyhawks, four Skyraiders and three Phantoms) from the same carrier struck the Loc Chao base. Simultaneously, the Ticonderoga dispatched six F-8E Crusaders to the torpedo boat bases at Quảng Khê and Bến Thuỷ and 26 other aircraft to bomb an oil storage depot at Vinh. Unfortunately, President Johnson’s premature television announcement that the raids were to take place may have warned the North Viêtnamese who put up a fierce barrage of anti-aircraft fire at all the targets resulting in the loss of two aircraft. Lieutenant (jg) Richard Christian Sather’s Skyraider from VA-145 was hit by AAA while on its third dive bomb attack and crashed just off shore from Thanh Hóa. No parachute was seen or radio emergency beeper heard and it was assumed that Sather died in the crash, the first naval airman to be killed in the war.58 Skyhawk pilot, 26-year-old Lieutenant (jg) Everett Alvarez Jr of San Jose, California, stationed aboard the Constellation in VA-144, who was on his first tour since graduating as a pilot in 1961 also took part in the ‘Pierce Arrow’ attack on torpedo boats at Hon Gay. During the night he had taken part in the abortive hunt for North Viêtnamese torpedo boats. Alvarez, who had been assigned his objective in advance, recalled years later: ‘I was among the first to launch off the carrier. Our squadron, ten airplanes, headed toward the target about 400 miles away - a good two hours there and two hours back. It was sort of like a dream. We were actually going to war, into combat. I never thought it would happen, but all of a sudden here we were and I was in it. I felt a little nervous. We made an identification pass, then came around and made an actual pass, firing. I was very low, just skimming the trees at about 500 knots. Then I had the weirdest feeling. My airplane was hit and started to fall apart, rolling and burning. I knew I wouldn’t live if I stayed with the airplane, so I ejected and luckily I cleared a cliff.’

Alvarez landed in shallow water, fracturing his back in the drop. Local North Viêtnamese militia soon arrived and took him to a nearby jail, where he was briefly visited by Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, who had been coincidentally touring the region at the time. Alvarez became something of a celebrity - the first of nearly 600 American airmen to be captured by the Communists during the Viêtnam War. Transferred to Hỏa Lò the notorious prison built in Hànôi by the French in 1896 which American PoWs held there until 29 March 1973 would nickname the ‘Hànôi Hilton’ he was held until the signing of the cease-fire agreement more than eight years later. Unable to get Alvarez to volunteer anything more than his name, rank and serial number, the North Viêtnamese isolated him in a squalid cell where huge rats darted about at night. Meanwhile he was kept on a starvation diet - including feathered blackbirds - which gave him chronic dysentery. ‘Suddenly I was thrown into this medieval environment and kept thinking, ‘God, why me?’ Alvarez recalled. ‘I fully expected the door to open and someone to say he was here to take me home. But as the days went by, I didn’t know how much longer it would be.’ Held in solitary confinement for fifteen months, Alvarez struggled to maintain his sanity by keeping the past alive in his mind. ‘Everyone, all the PoWs, looked up to Ev,’ says Paul Galanti who was captured two years after Alvarez. ‘He was one of those optimists who always thought we would get out the next day.’ Alvarez’s spirit was nearly broken in his seventh year of captivity, when the North Viêtnamese handed over correspondence announcing that his wife had divorced him, remarried and given birth to a child with her new husband. Everett Alvarez was released in Operation ‘Homecoming’ on 12 February 1973. He was known to other PoWs as the ‘Old Man of the North’ due to his longevity in the PoW camps.

Following the establishment of TF 77 aircraft carriers in the South China Sea in August 1964 it was six months before the US Navy was again in action although thirteen naval aircraft had been lost in accidents over Southeast Asian waters during this time. Although air strikes against North Viêtnam were part of President Johnson’s 2 December plan they were not immediately instigated. However, VC attacks on US facilities at Sàigòn on 24 December and Pleiku and Camp Holloway on 7 February caused President Johnson to order the first air strike against North Viêtnam since ‘Pierce Arrow’ in August 1964. In retaliation, the order was given for a strike from carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin. On 7 February ‘Flaming Dart I’, as the strike was code-named, saw 49 aircraft launched from the decks of the Hancock and Coral Sea against Viêt Công installations at Đồng Hới, while the Ranger sent thirty-four aircraft to bomb Vit Thu Lu. The new strike, code named ‘Flaming Dart I’, was due to be flown by the US Navy from the carriers Coral Sea, Hancock and Ranger. The targets were at Đồng Hới and Vit Thu Lu while other targets were hit by VNAF A-1s. The raid was led by Commander Warren H. Sells, Commander of Hancock’s Air Wing 21. In the event, monsoon weather forced the thirty-four aircraft of Ranger’s strike force to abort their mission against Vit Thu Lu but Đồng Hới’s barracks and port facilities were attacked by twenty aircraft from the Coral Sea and twenty-nine from the Hancock. The strike was carried out at low level under a 700 feet cloud base in rain and poor visibility. An A-4E Skyhawk from the Coral Sea, flown by Lieutenant Edward Andrew Dickson, a section leader of a flight of four aircraft of VA -155 was lost. (Dickson had had a miraculous escape from death just one year earlier when he was forced to eject from his Skyhawk over the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California during a training exercise. His parachute failed to deploy properly but he landed in a deep snowdrift that broke his fall causing only minor injuries.) About five miles south of the target, Dickson reported that he had been hit by AAA and requested his wingman to check his aircraft over as they commenced their run in to the target. Just as the flight was about to release its bombs, Dickson’s A-4E was seen to burst into flames, but despite a warning from his wingman, he continued with his bomb run and released his Snakeye bombs on target. Dickson headed out towards the sea but his aircraft became engulfed in flames and, although he was seen to eject, his parachute was not seen to deploy, and the aircraft crashed into the sea about half a mile offshore. There was no sign of Lieutenant Dickson in the water despite a SAR effort that continued for two days.

F-4B-21-MC Phantom BuNo 152218 of VF-21 ‘Free Lancers’ armed with two AIM-9B Sidewinder missiles and an AIM-7 Sparrow over Viêtnam in 1965. VF-21 was assigned to Carrier Air Wing 2 (CVW-2) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Midway (CVA-41) for a deployment to Viêtnam from 6 March to 23 November 1965. BuNo152218 was lost with VMFA-323, MAG-11 based at Đà Nẵng on 10 January 1966 after one of its bombs exploded prematurely. 1st Lieutenant R. T. Morrisey and the pilot, 1st Lieutenant G. E. Perry ejected, the latter sustaining major injuries.

The ‘Flaming Dart I’ mission of 7 February did not appear to have the effect on the North Viêtnamese that Washington had hoped for. On 10 February the Viêt Công struck at an American camp at Quy Nhın causing serious casualties. The immediate response to this was ‘Flaming Dart 2’, flown the following day59 when a total of ninety-nine naval aircraft from the Coral Sea, Hancock and Ranger were sent against NVA barracks at Chánh Hóa near Đồng Hới. The target was attacked in poor visibility with low cloud and the Coral Sea suffered two aircraft and one pilot lost on this raid. The first to be brought down was Lieutenant Commander Robert Harper Shumaker’s F-8D Crusader of VF-154, which was hit in the tail (possibly by debris from his own rockets) when he was pulling out from an attack on an anti-aircraft gun position. The aircraft’s afterburner blew out and the hydraulic system must have been damaged as the F-8D soon became uncontrollable forcing Shumaker to eject over land although his aircraft crashed a few miles off shore from Đồng Hới. Shumaker’s parachute opened about thirty feet above the ground and he broke his back on landing for which he received no medical treatment. A few minutes after Shumaker’s Crusader was shot down another wave of aircraft hit the Chánh Hóa barracks and another aircraft was lost. Lieutenant W. T. Majors of VA-153 from the Coral Sea in an A-4C was also attacking enemy AAA, using CBU-24 cluster bombs. After delivering his bombs he climbed the Skyhawk to 4,000 feet and set course for the carrier. However, his engine suddenly seized and could not be relit. Faced with no alternative, Majors ejected over the sea but was picked up almost immediately by a USAF rescue helicopter. Bomb damage assessments at Chánh Hóa showed that twenty-three of the seventy-six buildings in the camp were either damaged or destroyed during the raid.

In March, Operation ‘Rolling Thunder’, an air offensive against North Viêtnam, was launched and the Navy’s first strike took place on 18 March when aircraft from the Coral Sea and Hancock bombed supply dumps at Phu Văn and Vinh Sơn. The US Navy’s second ‘Rolling Thunder’ mission, on 26 March, resulted in the loss of three aircraft out of seventy dispatched. The ability of the North Viêtnamese air defence system to monitor US raids was a concern even in the early days of the war and the targets for this mission were radar sites at Bạch Long Vi, Cap Mùi Rắn, Hà Tĩnh and Vinh Sın. Lieutenant (jg) C. E. Gudmunson’s A-1H Skyraider of VA-215 from the Hancock was hit on his sixth pass over the target at Hà Tinh but he managed to fly to Đà Nẵng where he crash-landed about five miles west of the airfield. Commander Kenneth L. Shugart’s A-4E Skyhawk of VA-212 from the Hancock was hit on his second run as he dropped his Snakeye bombs on the radar site at Vinh Sơn. Shugart headed out to sea as the aircraft caught fire but the electrical system failed, forcing him to eject about ten miles off shore. He was picked up by a USAF helicopter. Lieutenant C. E. Wangeman, an F-8D pilot in VF-154 on the Coral Sea, did not realise that his Crusader, actually the Coral Sea Air Wing Commander’s aircraft, had been hit as he was attacking an AAA site at Bạch Long Vi. However, after leaving the target area his aircraft began to lose oil pressure and his wingman observed an oil leak. Wangeman climbed to high altitude and he managed to fly the aircraft for over 200 miles before the engine seized and he was forced to eject twenty miles north of Đà Nẵng. He was rescued by a USAF rescue helicopter.

A-6s BuNos 151789 and 151798 of VA-85 from the USS Kitty Hawk. On 21 April 1966 BuNo151798, flown by Commander Jack Elmer Keller and Lieutenant Commander Ellis Ernest Austin, and another Intruder took off just before dusk for a night attack on the heavily defended Tan Loc barracks and supply area on the coast ten miles north of Vinh. On the run in to the coast, Keller’s wingman had a problem and broke away to dump his bombs on Hon Mat Island, after which he waited for his leader to return. It was Keller’s intention to fly past the target then turn over high ground and bomb the target before heading straight out to sea. The wingman saw a bright flash, which he initially thought might have been a bomb explosion, but at the same time the Intruder disappeared from an E-2 Hawkeye’s radar screen. It was thought that the Intruder was either shot down or flew into high ground during the run in to the target.

On 29 March the Coral Sea’s air wing returned to Bạch Long Vi Island, which it had visited three days earlier. Again, seventy aircraft were despatched on the mission including six A-3B bombers from VAH-2. Three aircraft were lost in the first wave as they were attacking AAA sites around the target. Commander Jack H. Harris’ A-4E Skyhawk in VA-155 was hit during his low level bomb run causing his engine to wind down. Despite attempts to restart the engine the Commander had to eject over the sea close to the target but was picked up by a Navy ship. VA-154 pilot, Commander William N. Donnelly’s F-8D Crusader was hit during his first attack and his controls froze as he was making his second pass. He ejected at 450 knots at about 1,000 feet with the aircraft in an inverted dive and was extremely lucky to survive the ejection with only a fractured neck vertebra and dislocated shoulder. He came down in the shark-infested waters four miles north of Bạch Long Vi and for 45 hours he drifted in his life-raft, which sprang a leak and needed blowing up every twenty minutes. Twice during the first night he had to slip into the water to evade North Viêtnamese patrol boats that were searching for him. Fortunately he was spotted by an F-8 pilot on 31 March and was picked up by a USAF HU-16 Albatross amphibian. Another squadron commander, Commander Pete Mongilardi of VA-153, was almost lost when his A-4E was hit and had to be ‘towed’ back to a safe landing on the Coral Sea by a tanker as the Skyhawk leaked fuel as fast as it was being pumped in. Lieutenant Commander Kenneth Edward Hume’s F-8D in VF-154 was hit by ground fire as he was firing his Zuni unguided rockets at an AAA site on the island. A small fire was seen coming from the engine and Hume attempted to make for Đà Nẵng but after a few minutes the aircraft suddenly dived into the sea and although the canopy was seen to separate there was no sign of an ejection.

A USMC F-8 streaks past the explosion of another F-8’s bomb at Đà Nẵng in early 1966 before dropping his own munitions.

On Sunday 12 June 1966, 40-year old Commander Harold ‘Hal’ Marr, CO of VF-211 ‘Flying Checkmates’ equipped with F-8Es aboard the Hancock, became the first Crusader pilot to shoot down a MiG when he destroyed a MiG-17 51 miles northwest of Hảiphòng with his second Sidewinder missile at an altitude of only fifty feet.

The battle against the North Viêtnamese radar system continued on 31 March with further raids on the Vinh Sơn and Cap Mui Ron radar sites involving sixty aircraft from the Hancock and Coral Sea. Lieutenant (jg) Gerald Wayne McKinley’s A-1H in VA-215 from the Hancock was hit by ground fire during its second low-level bomb run and the aircraft crashed immediately. By this time both the USN and the USAF were flying regular missions over the Hồ Chi Minh Trail in Laos in an attempt to staunch the flow of arms and other supplies from North Viêtnam to the Viêt Công in the South. On 2 April Lieutenant Commander James Joseph Evans of VA-215 from the Hancock flying an A-1H was shot down by AAA north of Ban Mương Sen during an armed reconnaissance mission while in the process of attacking another AAA site.

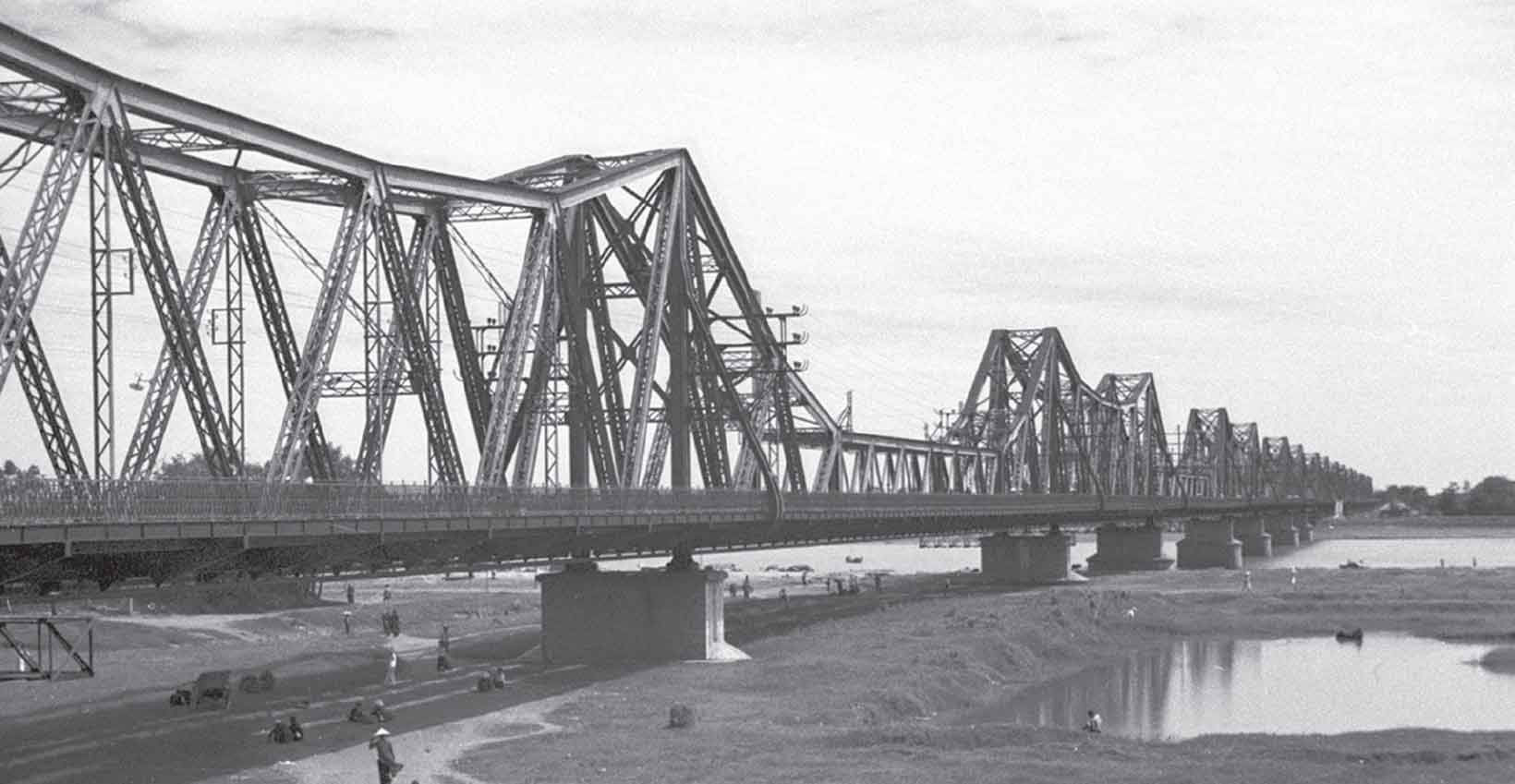

In March 1965 the decision to interdict the North Viêtnamese rail system south of the 20th parallel led immediately to the 3 April strike against the giant 540 feet by 56 feet Chinese-engineered Thanh Hóa road and rail Bridge which stands fifty feet above the Song Ma River. The bridge, three miles north of Thanh Hóa, the capital of Annam Province, in North Viêtnam’s bloody ‘Iron Triangle’ (Hảiphòng, Hànôi and Thanh Hóa) was a replacement for the original French-built Bridge destroyed by the Viêt Minh in 1945, blown up by simply loading two locomotives with explosives and running them together in the middle of the structure. Now a major line of communication from Hànôi seventy miles to the north and Hảiphòng to the southern provinces of North Viêtnam and from there to the DMZ and South Viêtnam, it was heavily defended by a ring of 37mm AAA sites that were supplemented by several 57mm sites following these initial raids.

Shortly after noon on 3 April USAF and USN aircraft of ‘Rolling Thunder’, ‘Mission 9-Alpha’, climbed into South-East Asian skies for the bridge, known to the Viêtnamese as the ‘Hàm Rồng’ (Dragon’s Jaw). Lieutenant Colonel Robinson Risner, a Korean War ace, was designated overall mission coordinator for the attack. He assembled a force consisting of seventy-nine aircraft - forty-six F-105s, twenty-one F-100s, two RF-101C’s tasked with pre and post-strike photographic reconnaissance runs over the target and ten KC-135 tankers to refuel the aircraft before they crossed the Thai border. The F-100s came from bases in South Viêtnam, while the rest of the aircraft were from squadrons TDY at various Thailand bases. Sixteen of the forty-six ‘Thuds’ were loaded with pairs of Bullpup missiles and each of the remaining thirty carried eight 750lb GP bombs. The aircraft that carried the missiles and half of the bombers were scheduled to strike the bridge; the remaining fifteen (and seven F-100s) would provide flak suppression. The plan called for individual flights of four F-105s from Koran and Takhli which would be air refuelled over the Mekong River before tracking across Laos to an initial point (IP) three minutes south of the bridge. After weapon release, the plan called for all aircraft to continue east until over the Gulf of Tonkin where rejoin would take place and a Navy destroyer would be available to recover anyone who had to eject due to battle damage or other causes. After rejoin, all aircraft would return to their bases, hopefully to the tune of The Hàm Rồng Bridge is falling down.

On 2 December 1966 during a night armed reconnaissance mission A-4Cs 145143 piloted by Commander Bruce August Nystrom (top) and 145116 (above) flown by Ensign Paul Laurance Worrell from the USS Franklin D Roosevelt disappeared near Phúc Nhạc, 50 miles down the coast from Hảiphòng. Worrell had been heard by another flight to warn his leader that he had a SAM warning. Commander Nystrom told the wingman to commence evasive action and then announced a SAM launch. A pilot some distance away saw two flashes on the ground about a minute apart, which were probably SAM launches, followed by two explosions in the air. It was assumed that the two Skyhawks were either hit by the SA-2s or flew into the ground trying to evade the missiles. The SAMs downed four American aircraft that day. Nystrom had been flying with the Navy since 1948 and had flown the F4U Corsair during the Korean War as well as the F8F Bearcat and the F2H Banshee. He joined VA-172 as executive officer in December 1964 and assumed command of the Squadron on 23 December 1965. In July 1985 the Viêtnamese returned the remains of Paul Worrell.

The sun glinting through the haze made the target somewhat difficult to acquire, but Risner led the way ‘down the chute’ and 250lb missiles were soon exploding on the target. Since only one Bullpup missile could be fired at a time, each pilot had to make two firing passes. On his second pass Risner’s aircraft took a hit just as the Bullpup hit the bridge. Fighting a serious fuel leak and a smoke-filled cockpit in addition to anti-aircraft fire from the enemy, he nursed his crippled aircraft to Đà Nẵng and to safety. The ‘Dragon’ would not be so kind on another day. The first two flights had already left the target when Captain Bill Meyerholt, number three man in the third flight, rolled his Thunderchief into a dive and squeezed off a Bullpup. The missile streaked toward the bridge and as smoke cleared from the previous attacks, Meyerholt was shocked to see no visible damage to the bridge. The Bullpups were merely charring the heavy steel and concrete structure. The remaining missile attacks confirmed that firing Bullpups at the ‘Dragon’ was about as effective as shooting BB pellets at a Sherman tank. The bombers, undaunted, came in for their attack, only to see their payload drift to the far bank because of a very strong southwest wind. 1st Lieutenant George C. Smith’s F-100D was shot down near the target point as he suppressed flak. The anti-aircraft resistance was much stronger than anticipated. No radio contact could be made with Smith, nor could other aircraft locate him. Smith was listed MIA and no further word has been heard of him.

The last flight of the day, led by Captain Carlyle S. ‘Smitty’ Harris, adjusted their aiming points and scored several good hits on the roadway and super structure. ‘Smitty’ tried to assess bomb damage, but could not because of the smoke coming from the ‘Dragon’s Jaw’. The smoke would prove to be an ominous warning of things to come.

The USN mounted two raids against bridges near Thanh Hóa on the 3rd. A total of 35 A-4s, sixteen F-8s and four F-4s were launched from the Hancock and Coral Sea. Lieutenant Commander Raymond Arthur Vohden of VA-216 from the Hancock who was flying an A-4C Skyhawk was hit by small arms fire during his first bombing run during an attack on a bridge at Động Phổ Thông about ten miles north of the ‘Dragon’. His wing-man saw the aircraft streaming fluid and the arrester hook drop down. Soon afterwards, Vohden ejected and was captured to become the Navy’s third PoW in North Viêtnam. The raids were the first occasion when the Viêtnamese People’s Air Force employed its MiG-17 fighters, thus marking a significant escalation of the air war in Southeast Asia. During this raid three MiG-17s attacked and damaged a Crusader when four of the F-8Es tried to bomb the bridge. The F-8E pilot was forced to divert to Đà Nẵng. This was the first time a MiG had attacked a US aircraft during the war in Southeast Asia. Captain Herschel S. Morgan’s RF-101 was hit and went down seventy-five miles southwest of the target area, seriously injuring the pilot. Captain Morgan was captured and held in and around Hànôi until his release in February 1973.

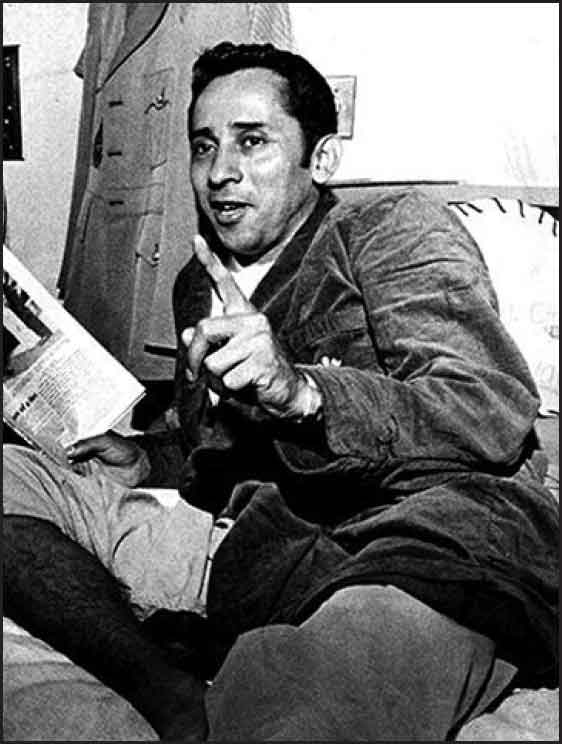

Commander Richard M. Bellinger describes his victory on 9 October 1966 when he destroyed a MiG-21.

RF-8G 144624 of Detachment 42, VFP-62 on the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt. This aircraft was lost on 6 September 1966 during a photographic reconnaissance mission when it was last seen to be manoeuvering close to the water about 10 miles off shore from Thanh Hóa before it crashed killing the pilot, Lieutenant (jg) Norman Lee Bundy. The crash was thought to have been a misjudgement of altitude above the sea.

When the smoke cleared, observer aircraft found that the bridge still spanned the river. Thirty-two Bullpups and ten dozen 750lb bombs had been aimed at the bridge and numerous hits had charred every part of the structure, yet it showed no sign of going down. A re-strike was ordered for the next day.

The following day, flights with call signs ‘Steel’, ‘Iron’, ‘Copper’, ‘Moon’, ‘Carbon’, ‘Zinc’, ‘Argon’, ‘Graphite’, ‘Esso’, ‘Mobil’, ‘Shell’, ‘Petrol’ and the ‘Cadillac’ BDA (bomb damage assessment) flight, assembled at IP to try once again to knock out the ‘Dragon’. On this day, Captain Carlyle ‘Smitty’ Harris was flying as call sign ‘Steel 3’. ‘Steel 3’ took the lead and oriented himself for his run on a 300 degree heading. He reported that his bombs had impacted on the target on the eastern end of the bridge. ‘Steel 3’ was on fire as soon as he left the target. Radio contact was garbled and ‘Steel Lead’, ‘Steel 2’ and ‘Steel 4’ watched helplessly as ‘Smitty’s aircraft, emitting flame for twenty feet behind, headed due west of the target. All flight members had him in sight until the fire died out, but observed no parachute, nor did they see the aircraft impact the ground. ‘Smitty’s aircraft had been hit by a MiG whose pilot later recounted the incident in ‘Viêtnam Courier’ on 15 April 1965. It was not until much later that it would be learned that ‘Smitty’ had been captured by the North Viêtnamese. ‘Smitty’ was held prisoner for eight years and released in 1973. Fellow PoWs credit Smitty with introducing the ‘tap code’ which enabled them to communicate with each other.

BuNo149993 A-4E of VA-163 ‘Saints’ from the USS Oriskany taking on fuel from KA-3B tanker 138974 of VAH-4 from the same carrier in the summer of 1967. On 26 May 1970, now with VA-152 on the USS Shangri-La this Skyhawk was abandoned during a tanker mission when the engine suddenly lost power. It was suspected that the A-4E had ingested fuel into the engine air intakes as the aircraft was taking on fuel from another tanker. The pilot survived and was picked up safe and sound.

MiGs had been seen on previous missions, but for the first time in the war, the Russian-made MiGs attacked American aircraft. ‘Zinc 2’, an F-105D flown by Captain James A. Magnusson, had its flight bounced by MiG 17s. As Zinc Lead was breaking to shake a MiG on his tail, ‘Zinc 2’ was hit and radioed that he was heading for the Gulf if he could maintain control of his aircraft. The other aircraft were busy evading the MiGs and Magnusson radioed several times before ‘Steel Lead’ responded and instructed him to tune his radio to rescue frequency. Magnusson’s aircraft finally ditched over the Gulf of Tonkin near the island of Hòn Mê and he was not seen or heard from again. He was listed MIA. Captain Walter F. Draeger’s A-1H (probably an escort for rescue teams) was shot down over the Gulf of Tonkin just northeast of the ‘Dragon’ that day. Draeger’s aircraft was seen to crash in flames, but no parachute was observed. Draeger was listed MIA. The remaining aircraft returned to their bases, discouraged. Although over 300 bombs scored hits on this second strike, the bridge still stood. From April to September 1965, nineteen more pilots were shot down in the general vicinity of the ‘Dragon’.

The threat of MiG activity over Southeast Asia resulted in increased efforts to provide combat air patrols and airborne early warning and the F-4 Phantom and F-8 Crusader were tasked with air defence of the fleet and protection of strike forces. On 9 April two Phantoms of VF-96 on the Ranger were launched to relieve two other aircraft flying a BARCAP (Barrier Combat Air Patrol) racetrack pattern in the northern Gulf of Tonkin. However, the first aircraft to launch crashed as it was being catapulted from the carrier. The aircraft’s starboard engine failed during the catapult shot and the aircraft ditched into the sea but both Lieutenant Commander William E. Greer and Lieutenant (jg) R. Bruning ejected just as the aircraft impacted the water and were rescued. Lieutenant (jg) Terence Meredith Murphy and Ensign Ronald James Fegan were then launched and took over as section leader with a replacement aircraft flown by Lieutenant Watkins and Lieutenant (jg) Mueller as their wingman. As the two Phantoms flew north they were intercepted by four MiG-17s that were identified as belonging to the air force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. The two Phantoms that were waiting to be relieved on BARCAP heard Murphy’s radio calls and flew south to engage the MiGs. The air battle took place at high altitude near the Chinese island of Hainan and Murphy’s Phantom was not seen after the MiGs disengaged. The aircraft was thought to have been shot down by the MiGs but a Chinese newspaper claimed that Murphy had been shot down in error by an AIM-7 Sparrow missile fired by another Phantom. One of the MiG-17s was seen to explode and was thought to have been shot down by Murphy during the dogfight but it was never officially credited due to the sensitivity of US aircraft engaging Chinese aircraft. Murphy’s last radio call was to the effect that he was out of missiles and was returning to base. Despite an extensive two-day SAR effort no sign of the Phantom or its crew was ever found.

On 8 May the US Navy mounted its first raid against a North Viêtnamese airfield when Vinh air base was attacked by a strike force from the Midway. Commander James David La Haye, the CO of VF-111, was attacking the airfield’s AAA defences with Zuni unguided rockets and 20mm cannon fire when his aircraft was hit by ground fire. The Crusader was seen to turn towards the coast with its wings level but streaming fuel until it crashed into the sea a few miles offshore near the island of Hon Nieu. No attempt at ejection was seen although the pilot had radioed that his aircraft had been hit. About six hours after the strike on Vinh airfield Detachment A, VFP-63, Midway’s photographic reconnaissance detachment flew a BDA mission to assess the damage done to the target. During the run over the airfield Lieutenant (jg) W. B. Wilson’s RF-8A Crusader was hit by ground fire and sustained damage to the fuel tanks, hydraulic system and tail fin. Despite the damage and loss of fuel, Wilson managed to make for the coast and fly south towards a tanker where he took on enough fuel to reach the carrier or Đà Nẵng. Unfortunately, soon after taking on fuel, two explosions were heard from the rear of the aircraft as either fuel or hydraulic fluid ignited. The aircraft’s controls froze and Lieutenant Wilson ejected over the sea about thirty miles off Đồng Hới from where he was rescued by a USAF Albatross.

Midway’s run of bad luck continued. On 27 May the US Navy flew a strike against the railway yards at Vinh, one of the most frequently hit targets in the southern part of North Viêtnam. Commander Doyle Wilmer Lynn, CO of VF-111 was attacking an AAA site near the target when his F-8D Crusader was hit by ground fire. Lynn, who had been one of the first Navy pilots to be shot down in South East Asia when his Crusader was shot down on 7 June 1964 over the Plain of Jars, radioed that the aircraft had been hit and the F-8 was seen to go out of control and hit the ground before an ejection could take place. On 1 June in preparation for further attacks on the railway yards at Vinh, the Midway sent Lieutenant (jg) M. R. Fields, one of its Detachment A, VFP-63, photographic reconnaissance RF-8A Crusader pilots, to check the state of damage and to see which areas needed to be attacked again. At 500 feet over the target the aircraft was hit by ground fire which damaged its hydraulic system. Fields felt the controls gradually stiffening as he raced for the sea. He was fortunate to be able to get over thirty miles from the coastline before the controls eventually froze solid and he was forced to eject. He was soon rescued by a USAF Albatross amphibian.

On 29 July 1967 an electrical anomaly discharged a Mk.32 Zuni rocket on the flight deck of the USS Forrestal in the Gulf of Tonkin killing 134 men, injuring 161 and writing off 21 aircraft.

A-4 Skyhawks of VA-146, F-4Js of VF-143, A-6 Intruders, an A-3B, RA-5C Vigilante and a RA-3B Skywarrior of VAP-61 painted glossy-black for night sorties over the Hó Chi Minh Trail in Laos on the crowded flight deck of the USS Constellation (CVA-64) in 1967. A few RA-3Bs operating with VAP-61 (and to a lesser extent, VAP-62) were usually based at Đà Nẵng but occasionally deployed to carriers at Yankee Station in the South China Sea off Đà Nẵng.

Next day two more Midway aircraft were lost. During a raid on a radar site a few miles south of Thanh Hóa, an A-4E flown by Lieutenant (jg) David Marion Christian of VA-23 was hit by AAA when pulling up from its second attack with Zuni rockets. The aircraft caught fire immediately and Christian radioed that his engine had flamed out. It could not be confirmed if Christian ejected from the stricken Skyhawk before it hit the ground. Thirty minutes after the aircraft was lost, an EA-1F Skyraider of Detachment A, VAW-13 arrived from the Midway to co-ordinate a SAR effort for Lieutenant Christian. As the Skyraider was about to cross the coast at low level near Sam Son, east of Thanh Hóa, it was hit by ground fire and crashed. The Midway lost its fifth aircraft in three days on 3 June during an armed reconnaissance mission in the ‘Barrel Roll’ area of Laos. Lieutenant Raymond P. Ilg’s A-4C Skyhawk of VA-22 was hit by AAA over Route 65 near Ban Nakay Neua, ten miles east of Sam Neua. The aircraft caught fire and Ilg ejected immediately. He evaded for two days until he was picked up by an Air America helicopter.

On 20 October 1967 with both legs shattered by North Việtnamese anti-aircraft fire, Lieutenant (jg) Denny Earl successfully lands his VA-163 Saints A-4E Skyhawk BuNo 149959, AH-300, aboard the USS Oriskany. Six days later this same Skyhawk was shot down over Hànôi. The pilot, John S McCain, spent 5½ years as a PoW. (USN)

On 17 June two VF-21 ‘Freelancers’ F-4Bs from the USS Midway (CVA-41) scored the first MiG kills of the war when they attacked four MiG-17s south of Hànôi and brought down two with radar-guided AIM-7 Sparrow missiles. One of the F-4Bs was flown by Commander Louis C. Page and his radar intercept officer, Lieutenant Jack E. D. Batson. The other was flown by Lieutenant John C. Smith and 33-year old Montclair, New Jersey-born Lieutenant Commander Robert B. Doremus his Naval Flight Officer (NFO) also serving as Radar Intercept Officer (RIO). They were each awarded the Silver Star. Lieutenant Commander Doremus citation for first of two Silver Star’s reads: ‘…Engaging at least four and possibly six FRESCO aircraft, Commander (then Lieutenant Commander) Doremus accounted for one confirmed kill and contributed to a second confirmed kill by the other F-4B aircraft in the flight by diverting the remaining enemy planes from their threat to the US striking forces. With heavy antiaircraft fire bursting throughout the patrol area, his crew relentlessly maintained their vigil and pressed forward their attack, seeking out and destroying the enemy aircraft and thereby preventing damage to friendly strike aircraft in the area.’

On 24 August on a mission to hit the ‘Dragon’s Jaw’ Bridge at Than Hòa, Doremus was flying with thirty-eight-year old Brooklyn, New York born Commander Fred Augustus Franke, commander of VF-21 in F-4B call sign ‘Sundown’ when they were hit by a SAM SA-2 at about 11,000 feet near the village of Phủ Banh, north of Than Hòa. They both successfully ejected and were captured in the rice fields almost immediately but his wingman had reported seeing no chutes, so they were declared killed in action (KIA).60

Catapult bridle cables are hooked up to an A-7A Corsair of VA-147 ‘Argonauts’ and F-4B Phantom 153014 of VF-21 ‘Freelancers’ on the flight deck of the USS Ranger in the Gulf of Tonkin on 14 December 1967. On 28 April 1968 153014 was pulling up from its attack on storage caves at Ben Thuy, just to the south of Vinh when AAA set the port wing on fire and the port engine had to be shut down. Lieutenant Commander Duke E. Hernandez headed out to sea but within a few minutes the starboard engine also caught fire, the hydraulic system failed and the aircraft went out of control so he and Lieutenant (jg) David J. Lortscher ejected close to a SAR destroyer about fifteen miles offshore. They were quickly rescued by a Navy helicopter. Lortscher ejected from another F-4 near San Diego on 14 September 1970 and again on 22 September 1971 when the canopy of his F-4 separated. On 15 October 1973, during an exchange posting with the Royal Navy he ejected from a Phantom for the fourth time. Hernandez had ejected from a Phantom during a raid on Hảiphòng on 16 December 1967.

On Sunday 12 June 1966 forty-year old Commander Harold ‘Hal’ Marr, CO of VF-211 ‘Flying Checkmates’ equipped with F-8Es aboard the Hancock became the first Crusader pilot to shoot down a MiG when he destroyed a MiG-17 fifty-one miles northwest of Hảiphòng with his second Sidewinder missile at an altitude of only fifty feet. ‘I’ve waited eighteen years to do that,’ Marr, of Roseburg, Oregon, said. He was also credited with a probable after blasting more MiGs with his 20mm cannon. He was one of a flight of Crusader pilots flying Combat Air Patrol for a flight of A-4 Skyhawks that were attacking the Đại Tấn military area, twenty-four miles northwest of Hảiphòng. Marr and his wingman, Lieutenant (jg) Philip V. Vampatella, aged twenty-six of Islip Terrace, New York were flying at 2,000 feet when the MiGs appeared from the east. ‘We were flying in the missile envelope around the Hảiphòng-Hànôi area,’ Marr said. ‘We wouldn’t be flying very high and take the chance of getting a telephone pole (missile) shoved into us.’ When Vampatella spotted the MiGs, he flew his plane into them and overshot them. For the next four minutes, at speeds between 350-550 mph and as low as fifty feet, Marr and the pilot of the communist jet banked and turned to get into position to shoot. Marr maneuvered his Crusader behind the MiG and fired a heat-seeking Sidewinder missile, which missed the MiG and streaked to earth. Marr was alone in the fight. Vampatella and a third pilot ran out of 20mm cannon ammunition and were low on fuel and returned to the ship. Marr manoeuvred his aircraft around and fired again at the MiG. ‘The missile clipped the tail off and it went right into the ground,’ Marr said. Marr sighted another flight of MiGs and the chase began again. Having used both of his Sidewinders on one MiG, Marr only had 20mm cannon fire, which he began firing at a second MiG. He hit it and saw parts of the plane’s wing fly off. Low on fuel and short on ammunition himself, Marr returned to his ship. The F-8 enjoyed the highest kill ratio of any fighter engaged in the Việtnam air war.

Nine days later, on 21 June, Lieutenant Vampatella shot down another MiG-17 while covering a rescue attempt to bring home an RF-8 pilot shot down earlier. On 9 October an F-8E pilot, Commander Dick Bellinger, CO of VF-162 from the Oriskany became the first Navy pilot to destroy a MiG-21 when he obliterated one of the enemy fighters with heat-seeking missiles during an escort mission for A-4s from the Intrepid.

At 1525 hours on 27 July 1965 Archie Taylor, commander, Det 4, Pacific Air Rescue Center (PARC) was notified that there was a downed pilot, southwest of Hànôi and not far from Hànôi. He was said to be in the river. Then at 1530 the word came in a second aircraft was down. A HH-43 ‘Pedro’ launched from LS-98 at 1532. They were next notified there was a mid-air collision about ten miles southeast of Udorn in Thailand at 1540. One chute was spotted. The accident was between two F-105Ds returning from their mission in the North. Then at 1549 Udorn reported that ‘Cedar 2’ was down just west of Hànôi. Two B-57 Canberra bombers were launched from Đà Nẵng. At 1610 the SAR force informed all hands that men were down ‘in the ring’ (in the middle of enemy forces) and that ground defences were southeast of the downed crew members. At 1620 Archie noted that another F-105D call sign ‘Dogwood’ was down, also up near Hànôi. ‘Dogwood’ was working with SAR forces on the radio, operating as a kind of controller, which meant he was on the ground and in pretty good shape. At 1650 the HC-54s controlling the SAR mission were told to stay out of the ring. A call also went out at this time to see if a HU-16 Albatross was on its way.

On 10 January 1968, F-4B 151506 (pictured) and F-4B 151499 of VF-154 on the USS Ranger, flew a radar-directed bombing mission over low cloud in Laos. As the aircraft set course for the return trip to the Ranger the leader inadvertently homed onto the TACAN of the northern SAR destroyer instead of that of the carrier. When the Phantoms broke out from the cloud they were over 100 miles from the Ranger and the aircraft had to be abandoned over the South China Sea when they ran out of fuel. All four crewmen were rescued.

F-4B BuNo150466 ‘Old Nick 204’ of VF-111 ‘Sundowners’ dropping Mk.82 500lb ‘buddy bombs’ using navigation fixes, over North Viêtnam with BuNo149457, ‘Screaming Eagle 113’ from VF-51 ‘Screaming Eagles’, both on the USS Coral Sea. BuNo150466 was lost on 2 September 1970 with VMFA‑115, MAG‑13 USMC at Chu Lai in a ground accident when taxiing to fuel pits. Three ground crew were killed.

Two heavily armed A-6A Intruder attack aircraft of VA-156 in the Gulf of Tonkin in July 1968 during a combat mission flown off the USS Constellation (CVA-64). On 18 December 1968 154150 now with VA-196 was shot down by ground fire 70 miles West of Đà Nẵng during a daylight ‘Steel Tiger’ strike. Lieutenant (jg) John Richards Babcock and Lieutenant Gary Jon Mayer were killed.

At 1710, a CH-3C Jolly Green ‘call sign Shed 85’ fired up his engines and was aloft by 1714. At 1743 another HH-43 was launched. At 1845 a report came in that ‘Canister Flight’ had a good location on ‘Dogwood’ and that he was okay. ‘Canister’ also reported that a CH-3C was about to go in after him. At 1905 ‘Healy 1’ who was flight lead said ‘Healy 2’ went in to the river and ‘Healy 1’ saw a dingy but never saw the pilot. ‘Healy 1’ was running out of fuel and had to leave and on his way out he reported seeing boats within 300 yards of the dingy. After getting refuelled and returning to the scene, ‘Healy 1’ saw nothing in the area. Also at 1905 a CH-3C was hovering over ‘Dogwood’ who was hiding in the woods but could not get at him with the hoist. So he looked for a place to land. At 1915 the SAR force reported picking up ‘Dogwood’ and all the SAR forces were on their way out. Dogwood was picked up and rescued.

This entire sequence of events was part of Operation ‘Spring High’, which was the first strike against Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites. The NVN introduced SAM missiles in the summer of 1965. Up to this point, the NVN felt it could get by with its anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), fighter aircraft and radar network. After all, many of the US air attacks were largely symbolic, so as not to cause undue concern in the USSR and China. Slowly but surely the US ramped up to hit the radar networks and other more important targets.

Captain William J. Barthelmas, Jr. flying F-105D ‘Pepper 02’ in the 357th TFS out of Korat RTAFB was KIA, hit by a SAM thirty miles from Hànôi. Major Jack G. Farr, flying F-105D ‘Pepper 01’ crashed in Thailand, obviously trying to make it home and was also killed. They were on their way out after hitting a SAM site thirty miles west of Hànôi. Barthelmas was apparently hit by a SAM but he was able to make his way back to Thailand. ‘Pepper 01’ of course stuck with him. On their way back to Thailand, ‘Pepper 01’ inspected ‘Pepper 02’ and said, ‘I can see daylight right through you.’ The battle damage was severe. The conjecture is Barthelmas’ hydraulics gave out and his aircraft unexpectedly pitched up. ‘Pepper 02’s tail slammed into ‘Pepper 01’s cockpit. Bathelmus ejected but his parachute did not fully open. He is said to have landed in a rice paddy alive, but with multiple injuries. Tragically, he drowned in the paddy. Also tragically ‘Pepper 01’ was sufficiently damaged that he crashed about ten miles south of Ubon RTAFB. Farr did not eject and was killed.

Captain Walter Kosko, flying F-105D 624257 ‘Healy 02’ in the 563rd TFS out of Takhli targeted a SAM site thirty miles west of Hànôi and reportedly was hit by AAA. He landed in a river and drowned. Kosko was part of a flight of four F-105Ds out of Takhli on a bombing mission over Phú Thọ Province. AAA fire was said to be intense. There was an explosion near Kosko’s aircraft and he reported he was hit and had smoke in his cockpit. He later ejected and flight members saw a fully deployed chute in the water and survival gear, but there was no voice contact and no beeper after ejection. His colleagues on the mission tried to find him even through heavy hostile fire, but to no avail. Later attempts to find his remains revealed that he was down in the Black River. US forces searched the river but could not find him. He was later declared dead - body not recovered.

Captain Kile Dag Berg flying F-105D 610113, call sign ‘Hudson 2’ in the 563rd TFS at Takhli and Captain Robert B. ‘Percy’ Purcell flying F-105D 6224252, call sign ‘Ceader 2’ in the 12th TFS out of Korat were both shot down about forty miles northwest of Hànôi and taken prisoner. Both men’s target was the barracks at Can Doi and they both were reportedly hit by AAA.61 Right after he dropped his napalm Berg’s aircraft was seen on fire from in front of the inlets past the afterburner. It slowly pulled up, rolled right and then crashed. Berg ejected at fifty feet and 540 knots which blew some panels in his chute and without a doubt gave him ‘one helluva jolt’ as well.

Captain Frank J. Tullo, flying F-105D 624407 call sign ‘Dogwood 02’ in the 12th TFS out of Korat, was rescued. Tullo’s group had entered the fray after most of the beating took place. Their job was ‘to clean up’ Tullo said when he arrived over the target area. ‘To a good Catholic boy, this was a description of hell.’ The enemy fire was the worst he had seen and the burning fires and smoke below was a cauldron. Tullo said they approached at about 200 feet and 700 knots. Right away he was hit, his fire warning lights blazing. ‘Dogwood 01’, Major Bill Hosmer, came over to take a look. Hosmer told him to get rid of his tanks and rocket pods to lighten the aircraft. Flames were now trailing about 200 feet behind him. He was still flying and had control. They were still over Hànôi. Hosmer told him to bail out, but Tullo refused, saying he could still fly. He wanted to make it to the hills of ‘Thud Ridge’- a north-south mountain range between US bases in Thailand and Hànôi - where a bail out might result in a rescue. But the aircraft then lost control and he had to bail out, but again, at the speed he was travelling, he really got whipped around on the way out. From his parachute Tullo could see Hànôi about twenty-five miles away. Once on the ground, he hid his chute and called on the radio and made contact. But his partners were running out of fuel and had to leave. After some time on the ground and attempting to climb up a hill, which was what they were taught to do - make the enemy climb the hill and if they do, then you are close to the top and can go over the top of the hill and try to hide - he heard an A-1H Spad, call sign ‘Canasta’ who had a good indication that ‘Dogwood 02’ was okay and that a CH-3C Jolly Green was closing in. ‘Canasta’ Flight consisted of two Navy A-1Hs. Then two F-105s came by and Tullo contacted them. They asked him to pop smoke so they could get his location. Tullo refused, fearing he would give away his location to the enemy, as he knew the enemy was coming to his area. Some enemy started climbing the hill; Tullo dug in to hide and the enemy troops moved away and down the hill. The hill strategy seemed to work.

Viêtnam People’s Air Force (NVNAF) Soviet- and Chinese-built MiG-17Fs and their pilots in North Viêtnam.

The CH-3C flown by Captain George Martin USAF was at NKP and was flying to LS-36 to pull SAR alert, call sign ‘Shed 85’. His USAF crew consisted of his co-pilot, Lieutenant Orville Keese, ‘hoist mechanic’ Sergeant Curtis Pert and pararescueman Sergeant George Thayer. Martin was told to divert to get ‘Dogwood 02’ but he had to land at LS-36 to drop off supplies and passengers and could not hover the way he needed to for a rescue with such a heavy load. After landing at LS-36, his number two engine warning lights indicated they had overheated; a condition which would normally mean he was grounded. But he was Tullo’s only chance at that moment. He was worried he would not be able to restart his engines, informed the crew he felt they should go get Tullo; the crew agreed, the engine started without a hitch and off he went. He had little idea of where he was going other than to head for Hànôi. About fifty miles from Hànôi he was met by ‘Canasta’ flight, flown by Lieutenant Commander Ed Greathouse and Holt Livesay from VA-25 embarked aboard the USS Midway. It was getting late, dusk was coming. ‘Canasta’ reported to Tullo he had a chopper and flew directly over Tullo’s position, with ‘Shed 85’ right behind him. Tullo expected something like a HH-43 Pedro and had never seen one this big. It turns out this would be the CH-3C Jolly Green’s first rescue. The Jolly crew had a very hard time pulling Tullo up the hoist, which was not yet designed for this kind of work. And, of course, the CH-3C’s engine started to overheat again but he lifted up, dragging Tullo through bushes etc into the air and finally found a spot where he could let him down on the ground. Tullo got out of his harness and the Jolly landed about fifty feet away. Incredibly, now they started receiving hostile fire from the ground. The ‘Jolly’ had all kinds of problems, an overheated engine, coming darkness, and clouds at altitude. Plus the crew had no maps of the area. The ‘Jolly’ crew hollered at Tullo to board. He did, diving through the door and off they went. Martin pointed the Jolly in the direction of LS-36 which was surrounded by enemy. LS-36 lit up landing lights by igniting flares in fifty-five gallon drums and Martin landed the CH-3C with all hands in one piece.

The notorious Thanh Hòa (Dragon’s Jaw’) bridge.

Napalm attack on a suspected Viêt Công position.

This was the farthest north a successful rescue had been made. Just a few weeks earlier, Captain Martin and his crews were flying support missions with the CH-3 in Florida! So here they are, now in the Việtnam War, flying a beat-up old CH-3 on a SAR mission, no previous SAR experience, a rigged up winch to pull up the downed aircrew member and they were penetrating deeply into the NVN and conducting the first CH-3 rescue mission in the war.

‘Spring High’ involved more than a hundred Air Force, Marine and Navy aircraft. A pair of EC-121 radar planes monitored VPAF (NVNAF) activity, directing the combat air patrol. Ten electronic warfare craft jammed the enemy radars. A dozen Phantoms and eight more F-104 Starfighters flew air cover. There were fifteen KC-135s for aerial refuelling and a search and rescue flight to recover downed aircrews. On the cutting edge, forty-six F-105s hit SAM sites and nearby barracks presumed to house the defenders with napalm and cluster bombs. Four RF-101s then streaked past to photograph the targets for bomb-damage assessment. ‘Spring High’ cost four F-105s over the targets, plus one more damaged so badly the aircraft lost control making an emergency landing at Udorn, colliding with its escort and destroying both warplanes. All the losses were inflicted by flak, not SAMs. One pilot was rescued. Damage assessment showed that one of the target-SAM sites had been a dummy and another was unoccupied. The Soviet Union did not respond openly, but Moscow secretly accelerated its shipment of SAMs to North Việtnam. These engagements in the summer of 1965 marked the beginning of a whole new facet of ‘Rolling Thunder’. Henceforth the air campaign featured extensive efforts to neutralize VPAF surface-to-air-missile installations. In fact, SAM site attacks were a major element in the next bimonthly plan for the air effort.’62

On 29 August Lieutenant Henry S. McWhorter of VFP-63, USS Oriskany flying RF-8A callsign ‘Corktip 919’ on a photo reconnaissance in Nghe An Province, North Việtnam when he was hit by enemy fire about twenty-five miles northwest of Vinh. Both he and his wingman had encountered heavy AAA at 8,000 feet. They took evasive action. McWhorter’s wingman reported him flying straight and level, but with no canopy or ejection seat. The wingman concluded the AAA hit in a location that fired off the ejection seat and probably killed McWhorter. The wingman reported McWhorter’s landing gear coming down as a result of the damage to the hydraulic systems. The aircraft entered a gentle glide until it hit the ground. Two A-1s were on the scene five minutes after the crash and said they saw a chute leaving the aircraft. However, other reports said no chute was sighted. A HU-16 Flying Albatross also responded, but had to abort due to an engine loss. Another one came to the scene, but again, no contact. There was no beeper heard. He was listed as killed/body not recovered as the assessment was that there was a slim hope of survival.63

Lieutenant Allan Russell Carpenter, born 14 March 1938 in Portland, Maine got his navy wings in November 1963 and flew A-4 Skyhawks in VA-72 in Viêtnam in 1965 on the USS Independence. ‘We operated as most ships did in air wings for three or four days or a week in South Viêtnam getting the ship exercised and pilots and equipment all ready to go and then we moved north and started flying missions. North Viêtnam in 1965 was exciting because we were putting our skills to use in the environment that we had been trained for. We were, after all, combat pilots and now it was our first exposure to combat. However, the ground and air defences were not what they later became. We flew road reconnaissance flights and we bombed bridges and some army barracks and things like that. Eventually my squadron was involved in the first attack on a mobile SAM site in North Viêtnam. My commanding officer led that flight and we destroyed the site. We developed tactics as a result. We lost a significant number of people on that cruise, many of whom I would see later in prison in North Viêtnam. On 13 September 1965 my roommate [Lieutenant (jg) Joe Russell Mossman] was shot down and killed in the southern part of North Viêtnam. We got home in early December.

An F-8D of VF-111 ‘Sundowners’ about to be launched from the No.2 catapult. During the Viêtnam War, VF-111 were based at NAS Miramar, California with the squadron making seven deployments to Southeast Asia, flying 12,500 combat sorties. In 1967-68, VF-111 deployed a less-than-full-strength detachment from USS Intrepid (CVS-11).

‘We enjoyed a few weeks off before the Navy had decided to move all the A-4s to Cecil Field in Florida. It took a while to get the squadron set up in its new digs and learn our way around. Then we started training because our squadron had been picked in Washington to turn right around and make another WestPac cruise from the east coast, on the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt, leaving in June. We stopped in Rio de Janeiro on the way, which was a nice break and then crossed the equator a time or two again. We got on the line in August 1966 and things were different this time around. Again, we spent a few days down in South Viêtnam getting ready. And I had been promoted at that time to lieutenant in the Navy. I was a flight leader; a combat veteran. I was also experienced in the ‘Iron Hand’ SAM suppression mission, which were kind of risky. In the air force it was called ‘Wild Weasel’.

‘The defences had improved considerably from 1965. There was a lot of flak. There were more MiGs in the air and a lot more surface-to-air missiles. Over the course of time the aircraft that I was flying in was hit on seven different occasions, one of which on 21 August 1966 resulted in very serious damage to the aircraft. I was able to make it back to the ship but could not wait around until they could clear the deck and get me back on board and I was forced to eject from my aircraft which was fully engulfed in flame. I was in the vicinity of the ship and at low altitude and relatively low airspeed and so it was a somewhat uneventful ejection. I was picked up by the ship’s helicopter and brought aboard, given a shot of whiskey and told to get some rest. Then the next morning I was the first aircraft launched off the ship, the old theory being that you get back on that horse that threw you before you get scared. And it seemed to work. I continued flying missions and in the interim we went back and forth to various ports. We went into Japan twice and got to see a little foreign culture and do some shopping, sending things back to my wife Carolyn.

‘We were back on the line on 1 November 1966. My mission on that day was to lead a flight of three A-4s, providing SAM suppression for a flight of photo F-8 Crusaders taking pictures of Hảiphòng Harbour, shipping and docks. After that portion of the mission I was to lead my flight on up the coast toward the border with China looking at coastal installations and seeing if we could find any patrol boats or vehicular traffic or trained traffic that we could attack in North Viêtnam. Unfortunately, that didn’t come to pass. The SAMs came on line. I was monitoring their radars and could tell that they were on line searching and when they launched the missiles I could hear them tracking. I looked down. It was a pretty dark, very rainy, miserable day everywhere except right where we were. For the first time in North Viêtnam I saw a light on the surface. These people were being pretty foolish to allow a light to be shown in a combat environment. The light got bigger and brighter and suddenly I realized that it was a SAM. I launched a Shrike anti-SAM radar missile at the site. It tracked properly and destroyed the radar trails. I followed up by leading my flight of three in an attack on a site. I was armed with four- or five-inch rockets from my first run. My wingers just had 500lb bombs. The flak was intense and it was big stuff; 85mm for the most part, some 57mm but not the little 37’s and 57’s that we normally encountered. Right in the pull-out over the target the place was in a shambles which gave me a lot of satisfaction. But about that time as I was pulling out I heard a very loud explosion. The airplane shook and my fire warning light came on. I knew that I’d been hit and I’d been hit hard. I told my wingmen that I had been hit and that we were headed inland. It only made sense to turn around and come back out and I just might as well drop my bombs on the way. So I said, ‘let’s put the bombs on them on the way out’ but the airplane was progressively either coming apart or failing to work the way it was supposed to. A lot of the systems fell off the line. Eventually, in the turn coming back around, I decided to just clean everything off on the bottom of the airplane and just drop it inert. All the bombs, drop tanks; everything that was on the bottom of the airplane came off, which made me go a lot faster than my wingmen because I was at a hundred percent power.

MiG-17Fs of the Viêtnam People’s Air Force (NVNAF) taxi out.

Sparrow and Sidewinder-armed F-4B-27-MC 153045 of VF-114 ‘Aardvarks’ from the USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) over the Gulf of Tonkin in March 1968. This aircraft was the US Navy’s final MiG killer when a Việtnam Peoples Air Force MiG-17 flown by Senior Lieutenant Luu Kim Ng was shot down by Lieutenant Victor Kovaleski and Lieutenant James R. Wise of VF-161 ‘Chargers’ from the USS Midway, near Hải Phòng, using an AIM 9 Sidewinder heat-seeking air-to-air missile. This was the last air combat victory by a US aircraft during the Việtnam War.

‘I headed back towards Hảiphòng harbour. My intent was to climb to altitude. By this time I had heard from my wingman that I was on fire and I was burning bad and he was advising me to get out. I didn’t want to get out of an airplane which seemed to be taking me where I wanted to go, so I just stuck with it. (Later he told me that all he could see was a fire ball with two wing tips sticking out of it). I got up to about 5,000 feet with the intention of going to 9,000 feet but at 5,500 feet the stick and the right rudder pedal went all the way in the right-hand corner and the airplane started a non-commanded rudder roll. By the time I could take stock I was almost inverted. Pilots just don’t really want to jump out of an airplane inverted. I had plenty of altitude so I let it go. I didn’t pull the power back because I didn’t want to be hanging forward in the straps. That’s not a good way to eject. By the time I came around to full upright the nose was forty-five to sixty degrees nose down. I was at full power and a clean airplane. I was accelerating pretty rapidly. I looked down at my air speed indicator and the needle was moving quite rapidly. It was passing 550 knots at that time when I pulled the face curtain to eject from the aircraft because there was no control anymore. I had already stowed my kneeboard and my flashlight and other things that might be in the way and could hurt me. I had two options for getting out. One was a handle between the legs which you would pull. I had used that first time and thought that was pretty neat. But the second time I was going so fast. The face curtain was designed to protect your face from damage from a high speed ejection and I decided to use it. I kept my knees together, my back up against the seat and my elbows in at my side and grabbed the face curtain with both hands and pulled. I heard the canopy go off, felt the rush of air and the noise level increased incredibly. It felt very much to me as though I might be lying on the ground between the railroad tracks as a freight train or passenger train rushed over. It was very loud. I continued to pull and felt the seat fire. Once the rocket stopped firing I was immediately separated from the seat and it started trailing behind me. I was still holding on to the face curtain. I lost a grip with one arm. The other arm caught the wind stream and my shoulder dislocated. The humeral head broke several pieces off the top of the arm and it started flailing around out in the wind. I felt the curtain cutter fire and it released and the elbow popped out. My right shoulder was already dislocated and the left was now dislocated and it broke, too, so, for a little while I was holding the curtain in my left hand and both arms and legs were flailing around and I was corkscrewing through the air at around 600 mph. The A-4 seat was not designed to protect you at those speeds. The pain was incredible. I didn’t see how anybody could survive that kind of pain. You think of it abstractly. You’re not screaming or yelling or anything like that. I guess this is what it’s like to die. Never having died before I wasn’t sure, but it seemed reasonable that that’s what it was like. It was quite conceivable that my arms could have been torn from my body. And then I could feel the chute pack snap open and suddenly I was just hanging in the chute. When the seat fires the force of gravity was supposed to be about 19 Gs. So you would very briefly weigh nineteen times more than you would normally weigh. The opening shock of the chute had to be almost twice that.

F-4B-28-MC BuNo153065 of VF-114 ‘Aardvarks’ is recovered on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) in the Gulf of Tonkin after a combat mission over North Viêtnam on 21 April 1968. VF-114 was assigned to Carrier Air Wing 11 (CVW-11) aboard the Kitty Hawk for a deployment to Viêtnam from 18 November 1967 to 28 June 1968.

‘I opened my eyes because I had them closed. And now I had a new problem to face because I was totally blind. But you react as you had been trained to do. I reached up with both hands to release my oxygen mask but it was not in its normal position. I kept reaching but I had no glove on this hand because it had been torn off in the ejection. I finally came right up against something hard and smooth and it seemed like it was wet. And I thought ‘that’s my skull’. I snapped the oxygen mask off and threw it away and reached up. The front of the helmet was around my right ear. So I grabbed the side of the helmet with my right hand and pulled around and suddenly I could see. It was one of the best feelings I’ve ever had. I was just in time to see where my aircraft had impacted the water. It had gone in almost vertically close to a mile below me. There was a big cloud of water and steam and smoke coming up. My right shoulder hurt like the devil but it was somewhat functional. The left arm didn’t work. There was no shoulder there.

‘I got my personal survival radio out with one hand and called up and said, ‘I’m okay, but don’t pick me up.’ I couldn’t get it back in the place where it was supposed to go and I could only get half of my flotation equipment inflated and I was getting close to the water. I hit going pretty fast and went down fairly deep. I was in Hảiphòng harbour. The canopy immediately started to pull me through the water. Just before I ran out of air the tugging on the chute suddenly stopped and I popped to the surface.

‘I still wasn’t out of the woods. I only had partial inflation of my flotation equipment. I was riding quite low in the water and it didn’t take long before I could feel something tugging at my legs. The risers on the chute had wrapped around my boots and with the waves moving me up and down I was gradually sinking and being pulled down by the chute. I couldn’t get the other part of my floatation inflated and I was within five or ten minutes at the most from drowning. I had to tip my head back to be able to get a breath of air occasionally but I could see two or three sailing vessels coming toward me. As they got closer I could see that they all had guns. My wingmen were flying cover for me trying to keep the boats away but I found out later that the guns jammed in both of my wingmen’s’ airplanes. You don’t really want to drop a bomb to try to save your buddy because you’re liable to kill him so they dropped their drop tanks trying to scare the boats away and keep them from picking me up, but they weren’t dissuaded at all. And the flak was awfully heavy. I found out later that a helicopter was on its way to get me but he got shot up pretty badly and had to turn around and go back. The next thing I knew there was a boat pulling up alongside me and a guy pointing a rifle at me and screaming very excitedly in Viêtnamese. He kept motioning up as though he wanted me to lift my arms up. I would have been happy to lift them up to show them that I was no threat but I couldn’t. I think the handle of my pistol could be seen by my chin and he was probably looking at that and figuring when I had an opportunity I was liable to try to shoot him. So I decided that he was more than likely going to shoot me before they could get me on board. I wondered what that was going to feel like. And if it hurts, how long will it hurt? But he didn’t shoot. One of the men on board reached down and grabbed my left hand to try to pull me up onto the boat. I screamed in pain. He let go, reached around and grabbed my other arm. That shoulder was dislocated too and I screamed again in pain. They just kept pulling and found the chute was pulling me down. Somehow they got that loose. I think they just cut it with a machete. And the next thing I knew I was on the deck of the boat. I had become increasingly aware that there was an awful lot of noise. A guy with a .30 calibre machine gun on a bi-pod with another guy directing him was trying to get good shots at my wingmen. I could see one of the guys coming in really low making a high speed pass and I wanted him to get out of there because he’s just going to get shot down. Just as he got in to where this guy with the machine gun started to fire, the boom came around. It probably weighed three or four hundred pounds and it caught him right in the back and pushed him over. Whew, the gun just started firing down in the water. Each time he started shooting at my wingmen, the boom would catch him in the back and down he’d go. And one time the other boat was in the way and he strafed right across the deck. It was a moment of slight humour and every little bit helps. Then things got quiet. The airplanes went away. I could hear some in the distance. The triple-A stopped firing.

A-7A Corsair ‘602’ of VA-27 ‘Royal Maces’ attached to CVW-14 preparing to launch from the USS Constellation in 1968.

F-4B 3011 of VF-213 after trapping on the USS Kitty Hawk in the Gulf of Tonkin on 28 January 1968. F-4B-28-MC BuNo 153068 (behind with ‘115’ on the nose) was flown on 18 May 1972 by Lieutenants Henry A. ‘Bart’ Bartholmay and Oran R. Brown, on their first combat mission over North Việtnam when they shot down a MiG-19 with an AIM-9 Sidewinder near Kep Air Base, northeast of Hànôi. On14 January 1973 when BuNo153068 was flown by Lieutenant Victor T. Kovaleski and Ensign D. H. Plautz of VF-161 ‘Chargers’ from the USS Midway (CVA-41) this aircraft was hit by 85mm AAA about 10 miles south of Thanh Hóa and began leaking fuel. After flying offshore the crew ejected and were rescued. This was the very last US aircraft lost to enemy action during the Việtnam War.

A heavily armed A-6A of VA-35 ‘Black Panthers’ heads for a target over North Viêtnam on 15 March 1968 while operating from the nuclear powered carrier USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) at ‘Yankee Station’. Combined USN and USMC A-6/KA-6D losses during the war in SE Asia totalled 67 aircraft.