Slavery and a Moral Science of Freedom

In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free—honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just—a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud.

—Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862

As a young man in the late 1970s and early 1980s I spent a lot of time on the road exploring California and the other western states, initially in my 1966 Ford Mustang, and then on a bicycle after I seriously took up cycling, riding long distances all over and across America. When I wasn’t listening to lectures and books on cassette tapes on my Sony Walkman, I would while away the time by counting the number of Denny’s vs. Sambo’s restaurants along any given stretch of highway. For a while it was close, but then suddenly Sambo’s went bankrupt and Denny’s Grand Slam Breakfast became my meal of choice at any time of the day or night.

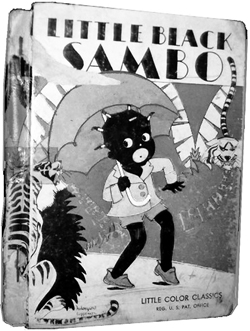

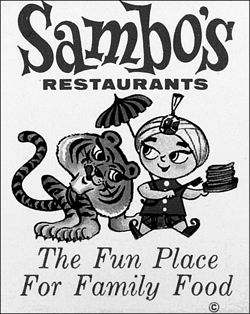

What happened to Sambo’s is emblematic of what happened across all of Western culture in the second half of the twentieth century: we became aware of the power of language and logos, symbols and gestures, to affect how we see and treat others—especially those of a different race. Sambo’s became embroiled in controversy over the restaurant chain’s name. The company was founded in 1957 by Sam Battistone Sr. and Newell Bohnett, who said that they derived the company’s name from the combined letters of their first and last names; but the duo also took advantage of the popularity of The Story of Little Black Sambo,1 and featured scenes from the book in menus and on the walls of their restaurants. The original story is about a dark-skinned Indian boy named Little Black Sambo who ventures out for a walk in the jungle and, in an unlikely turn of events, has his clothing expropriated by tigers. The tigers wind up quarreling over which of them is most attractive in Sambo’s clothes and eventually they chase each other around a tree so fast that they turn into butter, which Sambo’s mother, Black Mumbo, makes into pancakes. The restaurant marketers stayed true to the story in that they made the Sambo mascot Indian, but they portrayed him as a light-skinned Indian boy whose skin got lighter still from the fifties to the sixties until he was essentially an apple-cheeked white boy in a turban. The story was also modified—gone were Black Mumbo and Sambo’s father, Black Jumbo, and the unfortunate tigers no longer turned into butter but instead were treated to a stack of “the finest, lightest pancakes they ever ate”2 in exchange for returning Sambo’s clothes.

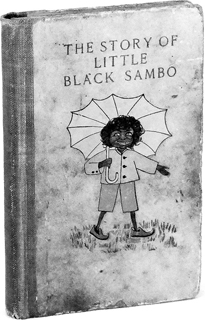

The trouble was that the Little Black Sambo featured on the cover of the US edition of the book was unmistakably African, and in time the two images—Indian and African black—morphed into a single likeness, reminiscent of “darky” or blackface iconography that was popular during the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. Increasingly, the word “Sambo” came to be understood as a pejorative label and a racist stereotype. There was a media feeding frenzy when the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) launched a formal protest and filed lawsuits against Sambo’s to block the opening of new restaurants in several northeastern states. The corporate suits at Sambo’s headquarters scrambled to explain, rationalize, and then respond by changing the names of some of the restaurants in those parts of the country where it was found offensive, to such innocuous titles as Jolly Tiger, No Place Like Sam’s, Season’s Friendly Eating, and even just Sam’s. As Nan Ellison, president of the Brockton, Massachusetts, NAACP, said, “I think I can go to Sam’s to eat without feeling degraded. I could not feel comfortable at Sambo’s when I reflected on the sacrifices made by demonstrators at sit-ins during the 1960s.”3 But it was all to no avail. By 1982 all but 1 of the 1,117 Sambo’s restaurants in 47 states had closed their doors, and the corporation filed for bankruptcy as a result of this and other business problems.4

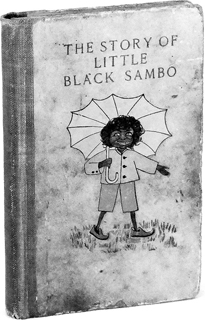

Looking at the cover and the illustrations of The Story of Little Black Sambo from an increasingly sensitive and perspicacious modern perspective it is not hard to understand why people of color found them offensive—they truly are cringeworthy (figure 5-1a–d). Images, names, and language matter. Decades later I recall that the boy featured in the restaurants had African features, even though a Google image search reveals that my memory is faulty. I even recollect seeing restaurant signs with the name Little Black Sambo’s, even though that too is a false memory. Now, on one level, the Sambo’s story sounds like political correctness run amok with the language police going too far, but it is a sign of moral progress that we’ve all become sensitized to how other people see the world, interchanging our perspectives with theirs.

Figure 5-1a

Figure 5-1b

Figure 5-1c

Figure 5-1d

Figure 5-1a–d. Little Black Sambo Then and Now

The Story of Little Black Sambo by Helen Bannerman is about an Indian boy (figure 5-1a) whose clothing is stolen by tigers, who chase each other around a tree so fast that they turn into butter, which Sambo’s mother then makes into pancakes. Sambo’s restaurant chain adopted the story and portrayed scenes from the book on the walls of its restaurants, but when “Sambo” became synonymous with offensive blackface iconography—as portrayed on the covers of early U.S. editions of the book (figure 5-1b)—and when the name mutated into a pejorative label and a racist stereotype, the restaurant chain faced a catastrophic public relations fiasco (figure 5-1c). Depicted here are early twentieth-century covers and a modern rendition (figure 5-1d) that reveal how much our racial and cultural sensitivities have changed in less than a century.5

The Sambo’s story illustrates one of the driving forces behind moral progress: those who champion human rights often begin with what we call things—how we talk and write about them—because so much of our thinking, including thinking about other people, is grounded in images and language. Of course, social change does not come about solely through the pristine powers of pure thought. The rights hard won by oppressed peoples throughout history have come about through the herculean efforts of the peoples themselves, in conjunction with their allies, through arduous direct political action. It almost inevitably takes some kind of direct deed (marches, sit-ins, sabotage, blockades, the destruction of property, outright civil war) to realize social transformation.

Still, even just-war theory demands there be reasons for the conflict beyond just Veni, vidi, vici. The abolition of slavery, in fact, came about at the time when its defenders were making intellectual arguments in support of it, but it was the better counterarguments, combined with political action (and in America, a war), that ultimately resulted in its collapse. Because the political action and the intellectual arguments generated in response to slavery produced the first of the great rights revolutions, we begin with it, and in keeping with my thesis that science and reason bend the moral arc of the universe, I will focus on the rational arguments and justifications for slavery and why they are wrong.

SLAVERY AND HUMAN RIGHTS

Of the many and various abuses and usurpations of humans by other humans, there is perhaps none so odious and oppressive as the ownership of one human being by another. This is slavery, and it has existed for as long as there have been those who, for the life of them, can’t see the problem with having a bunch of people that they don’t have to pay doing all of the soul-crushing grunt work for them. It is a custom that relies on an unspeakable lack of empathy, on the existence of a class- or caste-based, socially stratified society, and on a population and economy large enough to support it. Older than any written record, institutionalized slavery very possibly began at about the time of the agricultural revolution (with its accompanying ideas about ownership) approximately ten thousand years ago. The written record traces the practice back to 1760 BCE and the Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian document that treats slavery as a given. Out of the 282 laws dictated by King Hammurabi, at least 28 of them deal directly with slavery and what to do if, for example, a slave claims that you are not his master when you are indeed his master (cut off his ear), or a man buys a slave and the slave gets sick within the month (return the defective slave for a full refund), or a surgeon makes a large incision in your slave and your slave dies (the surgeon owes you a slave and must replace yours with an equally serviceable model).6

Slavery has now been outlawed in every country, though amazingly enough it was only a little over thirty years ago, in 1981, that the last country to outlaw the custom—Mauritania—finally did so. Of course, making slavery illegal is one thing; ending it is another. In Mauritania, for example, many people (mostly women) still live as slaves;7 worldwide, possibly millions are trapped in sex and labor slavery.8 Historically, the body count for the Atlantic slave trade alone may be as high as 10 million; the self-described atrocitologist Matthew White ranks it as the tenth-worst atrocity in the history of humanity.9 The process was beyond brutal, with a significant percentage of kidnapped victims perishing on the forced marches to the coastal forts where they were imprisoned, sometimes for months, until a slave ship came along. Many more died during the Middle Passage across the Atlantic, and still more in their first year in the New World as they were seasoned for work in the fields and mines. These human beings—mere beasts of burden—were stripped of their clothing, branded, displayed, inspected, and auctioned for sale to would-be buyers. The life of the slave truly was—pace Thomas Hobbes—solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

For millennia, religions in general, and Jewish, Christian, and Islamic churches in particular, have had little problem with the forced enslavement of hundreds of millions of people. It was only after the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment that rational arguments were proffered for the abolition of the slave trade, influenced by and citing such secular documents as the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. After an unconscionably long lag time, religion finally got on board the abolition train and became instrumental in helping to propel it forward.

Of course, one can find scattered throughout this long history the occasional religious objection to slavery, but these were remonstrations penned by Christians for Christians and against Christians who fully endorsed the institution, if they didn’t themselves participate. And, since nearly everyone before the twentieth century was religious, it is inevitable that any arguments against slavery would be made by religious people; thus it is the arguments, not the people, that require scrutiny. By the same logic, virtually all of the slave traders and slave masters were religious and grounded their justifications for slavery in the primary source of religious morality—a holy book. Some religions, such as Catholicism, fully endorsed slavery, as Pope Nicholas V made clear when, in 1452, he issued the radically proslavery document Dum Diversas. This was a papal bull granting Catholic countries such as Spain and Portugal “full and free permission to invade, search out, capture, and subjugate the Saracens and pagans and any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ wherever they may be, as well as their kingdoms, duchies, counties, principalities, and other property … and to reduce their persons into perpetual slavery.”10 These last few words—to reduce their persons into perpetual slavery—sound not just sinister to us, but also psychotic. They make perfect sense, however, in a Christian context, given that the Bible is itself a heedlessly proslavery tome. It’s hardly surprising then that it took almost two thousand years for Christians to twig to the fact that slavery is wrong. The spectacularly unreflective authors of the Bible had absolutely no problem with slavery whatsoever, as long as the slave owner didn’t actually beat his slaves blind and toothless (Exodus 21:26, 27). That was going just too far, although beating a slave to death was perfectly fine as long as the slave survived for a day or two after the beating. Then, when the slave died, it was appropriate to feel sorry for the unfortunate slave owner because it was he who had suffered a loss (Exodus 21:21).

Other biblical passages make it clear that God believes that slavery is a good idea, and so should you.

You may purchase male or female slaves from among the foreigners who live among you.—Leviticus 25:44

Are there any age restrictions? Surely it must be wrong to buy and sell children.

You may also purchase the children of such resident foreigners, including those who have been born in your land. You may treat them as your property, passing them on to your children as a permanent inheritance.—Leviticus 25:45

Thanks, Dad! But these laws only apply to foreigners. What about the people of Israel?

You may treat your slaves like this, but the people of Israel, your relatives, must never be treated this way.—Leviticus 25:46

Does this verse mean that the people of Israel were not to be slaves? No. God didn’t forbid his chosen people from enslaving one another—that would be extreme—but he did demand that more lenient protocols should be followed.

If you buy a Hebrew slave, he is to serve for only six years. Set him free in the seventh year, and he will owe you nothing for his freedom.—Exodus 21:2

Saying that the slave will owe his master nothing for his freedom seems a bit rich. Still, as far as treatment goes, a total of seven years of slavery isn’t too bad (if the slave survived the experience), but note that biblical law had a special way of holding even a freed slave hostage:

If he was single when he became your slave and then married afterward, only he will go free in the seventh year. But if he was married before he became a slave, then his wife will be freed with him. If his master gave him a wife while he was a slave, and they had sons or daughters, then the man will be free in the seventh year, but his wife and children will still belong to his master. But the slave may plainly declare, “I love my master, my wife, and my children. I would rather not go free.” If he does this, his master must present him before God. Then his master must take him to the door and publicly pierce his ear with an awl. After that, the slave will belong to his master forever.—Exodus 21:2–6

That’s a clever trick—bribe your male slave with a wife and children and then use those family relationships as a lever to make him yours forever. Seven years of clubs and chains just wasn’t quite enough misery, it would seem, for the Hebrew slave. He was bedeviled by a special category of emotional torture—a gut-wrenching choice between family and freedom. (Clearly being the chosen people has its drawbacks; one is reminded of Tevye appealing to God in Fiddler on the Roof: “I know, I know. We are your chosen people. But, once in a while, can’t you choose someone else?”)

Then there is this little gem from Exodus 21:7:

When a man sells his daughter …

Excuse me? When a man sells what? This must be some mistake in translation. But no. Sex trafficking as a form of slavery was widely practiced in biblical times, and so naturally the “good book” issued instructions on the proper way to sell one’s daughter into a lifetime of sexual servitude. As the father of a daughter myself, I find the mere contemplation of what is being negotiated here sickening:

When a man sells his daughter as a slave, she will not be freed at the end of six years as the men are. If she does not please the man who bought her, he may allow her to be bought back again. But he is not allowed to sell her to foreigners, since he is the one who broke the contract with her. And if the slave girl’s owner arranges for her to marry his son, he may no longer treat her as a slave girl, but he must treat her as his daughter. If he himself marries her and then takes another wife, he may not reduce her food or clothing or fail to sleep with her as his wife. If he fails in any of these three ways, she may leave as a free woman without making any payment.—Exodus 21:7–11

These passages are from the Old Testament. What does the New Testament say about slavery?

Slaves, obey your earthly masters with deep respect and fear. Serve them sincerely as you would serve Christ.—Ephesians 6:5

Christians who are slaves should give their masters full respect so that the name of God and his teaching will not be shamed. If your master is a Christian, that is no excuse for being disrespectful. You should work all the harder because you are helping another believer by your efforts.—1 Timothy 6:1–2

Teach slaves to be subject to their masters in everything, to try to please them, not to talk back to them, and not to steal from them, but to show that they can be fully trusted.—Titus 2:9–10

Clearly slave ownership was a given in the New Testament, as in the Old. Master/slave was just another relationship, like husband/wife or father/commodity. Paul’s Epistle to Philemon (the shortest book in the Bible at only 25 verses and 425 words) addresses the issue of slavery indirectly in that it was written by Paul to a leader of the Colossian church named Philemon, who owned a runaway slave named Onesimus—a slave who’d been converted to Christianity by Paul. Paul sent Onesimus back to his master with the letter, which instructed Philemon to treat his slave as a “brother beloved” instead of “a servant” (Philemon 1:16). Further, Paul even offered to pay Philemon any debt owed to him by Onesimus, “if he hath wronged thee at all” (Philemon 1:18). Tellingly, Paul does not suggest that Onesimus be set free, nor does he condemn slavery as the immoral custom it so obviously is. Instead, Paul inveigles his slaveholding Christian fellow to treat Onesimus as a member of the family. (That sounds nice, although given that fathers were allowed to sell their daughters, stone their sons, and put their unfaithful wives to death, it’s not the kind of family a person necessarily wants to be a part of. “Dysfunctional” doesn’t begin to cover it.) No doubt Paul was suggesting that Onesimus not receive the customary beating that the runaway slave might expect but, whatever he meant, yet again the kind of moral clarity one might expect to find in a book purported to be the final authority on the subject is nowhere to be found (which is why both supporters of slavery and abolitionists quoted from the Epistle to Philemon in their favor).

To be fair, biblical scholars and theologians, along with Christian apologists and defenders of the faith, rationalize these passages as ancient peoples dealing as best they could with an evil practice. In some cases it may be true that “slavery” or “bondage” really meant something more akin to “servant,” “bondservant,” or “manservant,” along the lines of a modern live-in maid or housekeeper. But this qualification misses the point. Where are the passages in the Bible condemning slavery on moral grounds? Where is there anything like a rational argument outlining why humans should not be so treated? Why is there not a straightforward commandment from Yahweh along the lines of Thou shalt not enslave thy fellow man? Imagine how different the history of humanity might have been had Yahweh not neglected to mention that people should never be treated as a means to someone else’s ends but should be treated as ends in themselves. Would this have been too much to ask from an all-powerful and loving God?

After the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, abolitionist arguments were made by the more progressive liberal Christian sects, such as the Mennonites, Quakers, and Methodists. It was these Christians who, in defiance of the norms found in the Bible, rejected the whole concept of slavery and became most vocal in the abolition movement. Among these was the great British crusader and abolitionist William Wilberforce (powerfully portrayed by actor Ioan Gruffudd in the film Amazing Grace). Wilberforce displayed incredible courage throughout his twenty-six-year campaign to abolish slavery (and in his push to found the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and other humanitarian movements), and there is no question that his motives were religious in nature. But note who Wilberforce’s most vociferous opponents were—his fellow Christians, who had to be badgered for a quarter century before coming around to his point of view. Plus, Wilberforce’s religious motives were complicated by his pushy and overzealous moralizing about virtually every aspect of life, and his great passion seemed to be to worry incessantly about what other people were doing, especially if what they were doing involved pleasure, excess, and “the torrent of profaneness that every day makes more rapid advances.” Wilberforce founded the Society for the Suppression of Vice after King George III issued the “Proclamation for the Discouragement of Vice” (at Wilberforce’s recommendation), which ordered the prosecution of those guilty of “excessive drinking, blasphemy, profane swearing and cursing, lewdness, profanation of the Lord’s Day, and other dissolute, immoral, or disorderly practices.”11

Wilberforce wasn’t happy just clipping the wings of the wayward at home; he also crusaded abroad for moral reform in Britain’s colony in India, insisting on Christian instruction and “religious improvement” of the citizens of that non-Christian nation because, he boasted, “Our religion is sublime, pure, beneficent; theirs is mean, licentious and cruel.” In fact, Wilberforce’s initial efforts were not concerned with the abolition of slavery but the ending of the slave trade (with existing slaveholders allowed to continue the practice that would presumably die out on its own in time without the outside source of slave replenishment). Slavery was not just an assault on the humanity of the slaves, Wilberforce argued, it was a blemish on the Christian religion that had for so long endorsed it. As he told the House of Commons on April 18, 1791, “Never, never will we desist till we have wiped away this scandal from the Christian name, released ourselves from the load of guilt, under which we at present labour, and extinguished every trace of this bloody traffic, of which our posterity, looking back to the history of these enlightened times, will scarce believe that it has been suffered to exist so long a disgrace and dishonour to this country.”12 Nevertheless, and tellingly, the House voted down Wilberforce’s bill on this occasion, 163–88.

THE COGNITIVE DISSONANCE OF SLAVERY

From a twenty-first-century perspective, in which we feel that we know instinctively that slavery is wrong, it is difficult to conceive that our immediate ancestors really believed that slavery was perfectly moral or, at the very least, not exactly immoral. We know that people commonly made proclamations about slavery being legal or moral or justified, but surely on the inside no one seriously believed that enslaving another human being was morally acceptable, did they? They did. And they made rational arguments to that effect, which were in time countered with better arguments on reason’s road to abolition.

Slavery is a case study on the power of self-deception as a work around for a psychological phenomenon called cognitive dissonance, or the mental tension experienced when someone holds two conflicting thoughts simultaneously; in this case: (1) slavery is acceptable and possibly even good, and (2) slavery is unacceptable and possibly even evil. For most of human history people simply accepted the first idea, but as Enlightenment ideas about people being treated equally began to percolate throughout societies, sentiments began to change toward the second idea, which produced cognitive dissonance.

The psychologist who first identified cognitive dissonance, Leon Festinger, described the psychological process this way: “Suppose an individual believes something with his whole heart; suppose further that he has a commitment to this belief, that he has taken irrevocable actions because of it; finally, suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong: what will happen? The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before. Indeed, he may even show a new fervor about convincing and converting other people to his view.”13 I suspect that increasing cognitive dissonance made the life of the slave owner increasingly uncomfortable throughout the nineteenth century, as the long-term shift in moral sentiments about the proper treatment of human beings was under way. The commonly accepted belief—that one group of humans may enslave another group—collided with the Enlightenment belief that humans are never to be treated as means to an end but are an end in and of themselves (Immanuel Kant) and that all people are created equal (Thomas Jefferson).

As this shift was under way, and ever more slaveholders experienced the cognitive dissonance this clash of ideas inevitably entails, something had to give—either slavery itself or the justifications for slavery through a host of ersatz rational arguments justified through the psychological phenomenon called self-deception, a well-documented cognitive strategy to attenuate cognitive dissonance, summarized by the evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers in The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life and by the psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson in their book Mistakes Were Made (but Not By Me).14 There is a logic to self-deception that works like this: In a selfish-gene model of evolution we should maximize our reproductive success through cunning and deceit. Yet game-theory dynamics (like those we considered in chapter 1) shows that if you are aware that other contestants in the game will also be employing similar strategies, it behooves you to feign transparency and honesty and lure them into complacency before you defect and grab the spoils. But if they are like you in anticipating such a shift in strategy they might pull the same trick, which means you must be keenly sensitive to their deceptions and they of yours. Thus we evolved the capacity for deception detection, and this led to an arms race between deception and deception detection.

Deception gains a slight edge over deception detection when the interactions are few in number and among strangers. But if you spend enough time with your interlocutors, they may leak their true intent through behavioral tells. As Trivers writes, “When interactions are anonymous or infrequent, behavioral cues cannot be read against a background of known behavior, so more general attributes of lying must be used.” He identifies three: Nervousness. “Because of the negative consequences of being detected, including being aggressed against … people are expected to be more nervous when lying.” Control. “In response to concern over appearing nervous … people may exert control, trying to suppress behavior, with possible detectable side effects such as … a planned and rehearsed impression.” Cognitive load. “Lying can be cognitively demanding. You must suppress the truth and construct a falsehood that is plausible on its face and … you must tell it in a convincing way and you must remember the story.” Unless self-deception is involved. If you believe the lie, you are less likely to give off the normal cues of lying that others might perceive: deception and deception detection create self-deception.

The self-deception of slave owners and proponents of slavery is well documented by the historians Eugene Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese in their book Fatal Self-Deception: Slaveholding Paternalism in the Old South. Slavery was not perceived by most slaveholders in the nineteenth century to be an exploitation of humans by other humans for economic gain; instead, slaveholders painted a portrait of slavery as a paternalistic and benign institution in which the slaves themselves were seen as not so different from all laborers—black and white—who toiled everywhere in both free and slave states; further, the South’s “Christian slavery” was claimed to be superior. “Decades of study have led us to a conclusion that some readers will find unpalatable,” Genovese and Fox-Genovese note. “Notwithstanding self-serving rhetoric, the slaveholders did believe themselves to be defending the ramparts of Christianity, constitutional republicanism, and social order against northern and European apostasy, secularism, and social and political radicalism.” Southern slaveholders could look around the world and see the hypocrisy with their own eyes. “Viewing the free states, they saw vicious Negrophobia and racial discrimination and a cruelly exploited white working class. Concluding that all labor, white and black, suffered de facto slavery or something akin to it, they proudly identified ‘Christian slavery’ as the most humane, compassionate, and generous of social systems.”15

As the ex-slave Lewis Clarke observed in his revealingly titled book Narrative of the Sufferings of Lewis Clarke, During a Captivity of More Than Twenty-Five Years, Among the Algerines of Kentucky, One of the So Called Christian States of North America: “There is nobody deceived quite so bad as the masters down South, for the slaves deceive them, and they deceive themselves.”16 The American architect, journalist, and social critic Frederick Law Olmsted summed up the theory of black incapacity on offer from both Northerners and Europeans: “The laboring class is better off in slavery, where it is furnished with masters who have a mercenary as well as a humane interest in providing the necessities of a vigorous physical existence to their instruments of labor, than it is in Europe, or than it will be in the North.”17 Consider the range of rationalizations employed by people at the time to reduce cognitive dissonance—unconsciously through the process of self-deception—documented by the Genoveses:

The negro has never yet found a sincere friend but his master.—George M. Troup, 1824, “First Annual Message to the State Legislature of Georgia.”18

My husband’s influence over the slaves is very great, while they never question his authority, and are ever ready to obey him implicitly, they love him!—Frances Fearn of Louisiana19

We, above all … were guarding the helpless black race from utter annihilation at the hands of a bloody and greedy ‘philanthropy,’ which sought to deprive them of the care of humane masters only that they might be abolished from the face of the earth, and leave the fields of labor clear for that free competition and demand-and-supply, which reduced even white workers to the lowest minimum of a miserable livelihood, and left the simple negro to compete, as best he could, with swarming and hungry millions of a more energetic race, who were already eating one another’s heads off.—E. A. Pollard, 1866, Southern History of the War 20

Negroes are a thriftless, thoughtless people. Left to themselves they will over eat, unseasonably eat, walk half the night, sleep on the ground, out of doors, anywhere.—Virginia slaveholder, 183221

Nine-tenths of the Southern masters would be defended by their slaves, at the peril of their own lives.—Thomas R. R. Cobb, 185822

The twisted psychology employed to assuage the dissonance was well expressed by Chancellor William Harper of South Carolina when he said, “It is natural that the oppressed should hate the oppressor. It is still more natural that the oppressor should hate his victim. Convince the master that he is doing injustice to his slave, and he at once begins to regard him with distrust and malignity.”23 In her 1994 sociological analysis of gender, class, and race relations, The Velvet Glove, the sociologist Mary R. Jackman identified what I think is more appropriately labeled as cognitive dissonance: “The presumption of moral superiority over a group with whom one has an expropriative relationship is thus flatly incompatible with the spirit of altruistic benevolence, no matter how much affection and breast-beating accompanies it. In the analysis of unequal relations between social groups, paternalism must be distinguished from benevolence.”24 You can hear the rationalization in the words of South Carolina governor George McDuffie in 1835: “The government of our slaves is strictly patriarchal, and produces those mutual feelings of kindness which result from a constant interchange of good offices.”25 Whatever you call it, self-deceptive paternalism masquerades as altruism (“I’m helping these people”) or reciprocity (“I’m giving back to these people after they gave for me”), and it may be an inevitable stage between slavery and freedom. Lest one lapse for even a moment and think there was something benevolent to Southern slavery, screen Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave for a visceral reminder of the inhumanity of this so-called paternalism—the chains of bondage; the mouthpieces of silence; the filth of living quarters; and the beatings, hangings, and especially the slashing, searing pain of the whip.

ENLIGHTENMENT REASON AND THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY

There is considered and considerable debate among scholars and historians about what led ultimately to the abolition of slavery. However, focusing strictly on the arguments, a brief review is instructive with an eye toward the arguments that were used against the institution.

Starting with religion, as the British historian Hugh Thomas noted in his monumental study The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440–1870, “There is no record in the seventeenth century of any preacher who, in any sermon, whether in the Cathedral of Saint-André in Bordeaux, or in a Presbyterian meeting house in Liverpool, condemned the trade in black slaves.”26 Instead, what few objections there were often had a ring of pragmatism to them, as in a 1707 letter from the secretary of the Royal Africa Company, Colonel John Pery, to his neighbor William Coward, who was considering sponsoring a slave voyage. It was “morally impossible that two tier of Negroes can be stowed between decks in four feet five inches,” he said. One tier, however, was perfectly acceptable in terms of profitability, given that the death rate on overpacked slave ships was a whopping 10 to 20 percent in the Middle Passage between Africa and America. Even religious-sounding objections were suspiciously expedient in their reasoning, as reflected in this observation by ship’s surgeon Thomas Aubrey, a doctor on the slave ship Peterborough, when he mused that the inhumanity suffered by their cargo might be compensated for in the next life: “For, though they are heathens, yet they have a rational soul as well as us; and God knows whether it may not be more tolerable for them in the latter day [of judgment] than for many who profess themselves Christians.”27

In America, the Quaker William Edmundson penned a letter in 1676 to his fellow Quakers in all slaveholding colonies and territories that slavery was un-Christian because it was “an oppression on the mind.” This was met with a denunciation by the founder of the colony of Rhode Island, Roger Williams—himself a Protestant theologian—that Edmundson was “nothing but a bundle of ignorance and boisterousness.” Shortly thereafter, in 1688, a group of German Quakers in Germantown (Philadelphia) issued a petition against slavery, arguing that it violated the Bible’s Golden Rule, but it went nowhere and lay dormant until it was rediscovered in 1844 and used in the abolitionist movement that had already taken root there. In fact, two prominent Quakers of Philadelphia—Jonathan Dickinson and Isaac Norris—were themselves slave traders, and there was even a slave ship named the Society that belonged to Quakers in the early eighteenth century; the captain, Thomas Monk, recorded that in 1700, during the transport of 250 slaves from Africa to America, 228 of them were lost in the Middle Passage.28 As Hugh Thomas notes in summing up the relationship between religion and slavery:

In all the richer parts of New York, Dominicans and Jesuits, Franciscans and Carmelites still had slaves at their disposal. The French Father Labat, on his arrival at the prosperous Caribbean colony of Martinique in 1693, described how his monastery, with its nine brothers, owned a sugar mill worked by water and tended by thirty-five slaves, of whom eight or ten were old or sick, and about fifteen badly nourished children. Humane, intelligent, and imaginative though Father Labat was, and grateful though he was for the work of his slaves, he never concerned himself as to whether slavery and the slave trade were ethical.29

It was not until late in the eighteenth century that objections to slavery were marshaled on ethical grounds, as noted by one prominent Bostonian: “About the time of the Stamp Act [1765], what were before only slight scruples in the minds of conscientious persons, became serious doubts and, with a considerable number, ripened into a firm persuasion that the slave trade was malum in se.” Evil in itself. That attitude was slow in coming. As late as 1757, the Huguenot rector of Westover, Peter Fontaine, wrote to his brother Moses about their “intestine enemies, our slaves,” noting, “To live in Virginia without slaves is morally impossible.” It was also economically problematic, and as Hugh Thomas notes, “None of these prohibitions … was decided upon for reasons of humanity. Fear and economy were the motives.”30

What ultimately brought about the abolition of slavery? According to Thomas, “The great wave of ideas, and emotions, known in France, and those who followed her, as the Enlightenment, was (in contrast to the Renaissance) hostile to slavery, though not even the most powerful intellects knew what to do about the matter in practice.”31 Enlightenment ideas transformed into laws, coupled with state enforcement, is what ultimately secured the end of the practice—an end that unfolded in ever more rapid escalation once it took off in the late eighteenth century. But make no mistake about it, the moral arguments that undermined slavery were not enough to bring about the abolition of it; many people and countries had to be dragged kicking and screaming up the moral ladder, as evidenced by the fact that after it outlawed slavery in 1807, the British Royal Navy had to patrol the African coast in search of illegal slave trade for more than sixty years, until 1870, seizing nearly 1,600 ships and liberating more than 150,000 slaves in the process.32 And, as previously noted, in the United States it took the deaths of more than 650,000 Americans in the Civil War to finally bring about slavery’s end there.

In the long run, however, it is the force of ideas even more than the force of arms that marshal moral advancement, as notions such as slavery gradually inch, by degrees, from morally good to acceptable to questionable; to unacceptable to immoral to illegal; and finally they shift altogether from unthinkable to utterly unthought of. What follows is a representative sample of nonreligious (secular) arguments against slavery proffered by Enlightenment philosophers that were highly influential in the abolition of slavery.

In his fictional 1756 Scarmentado, the widely read Voltaire had his African character turn the tables on a European slave trading ship captain, explaining to him why he enslaved the white crew: “You have long noses, we have flat ones; your hair is straight, while ours is curly; your skins are white, ours are black; in consequence, by the sacred laws of nature, we must, therefore, remain enemies. You buy us in the fairs on the coast of Guinea as if we were cattle in order to make us labor at no end of impoverishing and ridiculous work … [so] when we are stronger than you, we shall make you slaves, too, we shall make you work in our fields, and cut off your noses and ears.”33

Montesquieu, the Enlightenment philosopher we met in chapter 2, argued in his highly influential 1748 work The Spirit of the Law that slavery was bad not only for the slave but also for the slave master; the former for the obvious reason that slavery prevents a person from doing anything virtuous; the latter because it leads a person to become proud, impatient, hard, angry, and cruel.34

In the entry for the slave trade in Denis Diderot’s monumental 1765 Encyclopédia, which was devoured by intellectuals throughout the Continent, Great Britain, and the colonies, the author wrote, “This purchase is a business which violates religion, morality, natural law, and all human rights. There is not one of those unfortunate souls … slaves … who does not have the right to be declared free, since in truth he has never lost his freedom; and he could not lose it, since it was impossible for him to lose it; and neither his prince, nor his father, nor anyone else had the right to dispose of it.”35

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his 1762 Du Contrat Social (The Social Contract)—which was so influential in the intellectual foundation of the US Constitution—rejected slavery as being “null and void, not only because it is illegitimate, but also because it is absurd and meaningless. The words ‘slavery’ and ‘right’ are contradictory.”36

From mainland Europe secular sentiments against slavery migrated to the British Isles and were inculcated and expanded upon in the Scottish Enlightenment. In A System of Moral Philosophy, the Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson concluded that “all men have strong desires of liberty and property” and that “no damage done or crime committed can change a rational creature into a piece of goods void of all right.”37 Hutcheson’s student Adam Smith applied this principle in his first book, in 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, to argue, “There is not a negro from the coast of Africa who does not … possess a degree of magnanimity which the soul of his sordid master is scarce capable of conceiving.”38 In time, such arguments found their way into the legal system, such as through the writings of the judge Sir William Blackstone, whose 1769 Commentaries on the Laws of England outlined a legal case against slavery, then pronounced that “a slave or a negro, the moment he lands in England, falls under the protection of the laws and, with regard to all natural rights, becomes, eo instanti [instantly], a freeman.”39

The influence of both the French and the Scottish Enlightenments on the Founding Fathers and framers of the US Constitution is well known. Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, George Washington, and the others are considered to be both products of the Enlightenment and promoters of its philosophy of science and reason as the bases of a moral social order in the New World.

SLAVERY AND THE PRINCIPLE OF INTERCHANGEABLE PERSPECTIVES

Slavery is morally wrong because it is a clear-cut case of decreasing the survival and flourishing of sentient beings. But why is that wrong? It is wrong because it violates the natural law of personal autonomy and our evolved nature to survive and flourish; it prevents sentient beings from living to their full potential as they choose, and it does so in a manner that requires brute force or the threat thereof, which itself causes incalculable amounts of unnecessary suffering. How do we know that’s wrong? Because of the principle of interchangeable perspectives: I would not want to be a slave, therefore I should not be a slave master. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is, in fact, the very argument made by the man who did more than anyone else in the United States to put an end to slavery, Abraham Lincoln, who, in 1858, on the eve of the American Civil War that would be fought in part to end the institution, declared, “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master.”40

This is also another way to formulate the Golden Rule: “As I would not want someone else to make me a slave, so I should not make someone else be a slave.” In modern parlance, it is a description of the evolutionary stable strategy of reciprocal altruism: “I will scratch your back instead of being your master, if you will scratch my back and not make me a slave.”

The principle of interchangeable perspectives is also a restatement of John Rawls’s “original position” and “state of ignorance” arguments, which posit that in the original position of a society in which we are all ignorant of the state in which we will be born—male or female, black or white, rich or poor, healthy or sick, Protestant or Catholic, slave or free—we should favor laws that do not privilege any one class because we don’t know which category we will ultimately find ourselves in.41 This can be restated in this context thusly: “As I would not want to live in a society in which I am a slave, so I will vote for laws that outlaw slavery.”

In an unpublished note penned in 1854, Lincoln outlined the argument in what to our modern ears sounds like a perfect articulation of a behavioral game analysis. In his refutation of the arguments made in his day that the races should be ranked by skin color, intellect, and “interest” (by which Lincoln meant economic interest), Lincoln wrote the following:

If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A.?

You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

You do not mean color exactly?—You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own.

But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.42

Lincoln is here making a clearly secular argument for equality, reasoning his way from premises to a conclusion. Nowhere did he aver that his inspiration for the abolition of slavery came from religion. In point of fact, Lincoln was not a believer in any traditional sense of the word. After his assassination, the executor of his will and his longtime friend Judge David Davis said of Lincoln, “He had no faith in the Christian sense of the term.” Another one of his friends, Ward Hill Lamon, who knew him from his early years as a lawyer in Illinois to his presidency, affirmed, “Never in all that time did he let fall from his lips or his pen an expression which remotely implied the slightest faith in Jesus as the son of God and the Savior of men.”43

Instead, the above passage reflects the influence on Lincoln of Euclid’s Elements of Geometry, of which he was an avid reader and made reference to the mathematical propositions and how such reasoning might apply to human affairs. In the above passage, A and B are interchangeable elements of the proposition of the right to enslave—as A would not be a slave to B, A cannot be a master to B. In Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln, the screenwriter Tony Kushner has the great emancipator explain Euclid’s axiom in the context of a discussion on the equality of the races: “Euclid’s first common notion is this: Things which are equal to the same thing are equal to each other. That’s a rule of mathematical reasoning. It’s true because it works. Has done and always will do. In his book Euclid says this is self-evident. You see, there it is, even in that 2,000-year-old book of mechanical law it is a self-evident truth.” Although Lincoln never actually uttered those words, there is every reason to think that he would have made just such an argument because it’s precisely what is implied in his 1854 argument that A is interchangeable with B.44

In fact, the subsequent lines to Lincoln’s formulation of the principle of interchangeable perspectives—“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master”—are usually left off: “This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.” For a democracy to thrive, its citizens must also thrive, because a democracy is the sum total of its individual members. And remember, it is individual people who feel pain and suffer, not collectivities such as democracies. Thus the debate over slavery in Lincoln’s time reflected deeper and lasting moral principles that go to the heart of the source of government and the recognition of all human rights. As Lincoln noted in his seventh and final debate, on October 15, 1858, with Stephen A. Douglas—who famously declared in their debates, “I positively deny that he [the black man] is my brother or any kin to me whatever”45—the principle at stake was the freedom of the individual to flourish versus the divine right of kings to rule:

That is the real issue. That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent. It is the eternal struggle between these two principles—right and wrong—throughout the world. They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time; and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, “You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.” No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.46

Lincoln’s ultimate moral avowal was simple, and he made it in April 1864 while the body count of the Civil War had ticked up to more than half a million dead: “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”47

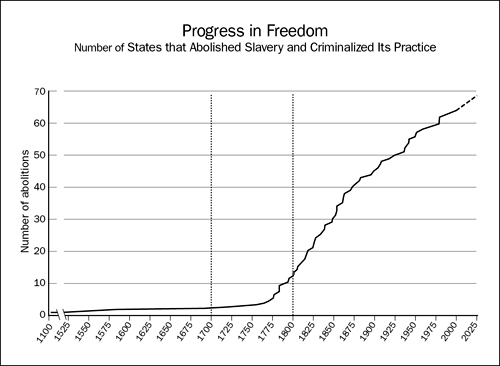

Figure 5-2 shows the abolition and criminalization of slavery by political states around the world from 1117, when Iceland became the first state to abolish slavery. Progress was desperately slow and halting for centuries. After the American Declaration of Independence in 1776, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789, and various other Enlightenment-inspired secular works on human rights became influential in the nineteenth century, the rate of slavery abolition and the spread of freedom escalated, culminating in 2007 and 2010, when Mauritania and the United Kingdom, respectively, made slavery a crime across the board. I have extended the dashed line to 2025 to reflect the fact that although slavery is illegal everywhere on Earth, it is still practiced in the form of sex trafficking in parts of Southeast Asia and elsewhere, and as slave labor in parts of Africa and elsewhere.

Figure 5-2. The Abolition and Criminalization of Slavery by Political States, 1117–2010

From the Wikipedia entry for “Abolition of Slavery Timeline.” Iceland was the first country to officially abolish slavery, in 1117, and the United Kingdom was the latest to make slavery a crime, in 2010. The dashed line to 2025 represents the fact that even though slavery has been legally abolished in all countries, in reality it is still practiced in the form of sex trafficking and slave labor, so there is headway still to be made.48

Unfortunately, the practice of slave labor and sex trafficking is ongoing in poorer regions of the world. The organization End Slavery Now estimates that there are as many as thirty million people enslaved in this manner,49 although a number of journalists and scholars who study the subject hold that this figure is very likely inflated by an order of magnitude based on unreliable data and estimates.50 As a percentage of the world’s population, however, all forms of slavery are at the lowest they’ve ever been. Nevertheless, people are still being exploited, and we need to end it. The Walk Free Foundation has identified ten countries that hold about 70 percent of the world’s slaves, with India, China, and Pakistan being the worst offenders. The index includes in its definition of slavery, “forced labour of men, women, and children, domestic servitude and forced begging, the sexual exploitation of women and children, and forced marriage.”51

The photographer Lisa Kristine has visually documented the brutality of such practices as sex trafficking and slave labor through her photography,52 and Free the Slaves cofounder Kevin Bales outlines how to combat these particular horrors, and how his organization intends to end all forms of it within a quarter century.53 As Bales explains, this form of slavery is economic in nature—“People do not enslave people to be mean to them; they do it to make a profit”—and the price of slaves has dropped dramatically from a historical average of $4,000 per slave in 2010 dollars to $90 per slave today. The reason for the drop in price is due to an increase in supply: with an exploding global population, there are a billion vulnerable people to exploit. It’s a bonanza for enslavers, whose modus operandi is to trick impoverished people, usually with the offer of a job. “They climb into the back of the truck, they go off with the person who recruits them, 10 miles, 100 miles, 1,000 miles later they find themselves in dirty, demeaning, dangerous work, they take it for a little while, but when they try to leave—Bang!—the hammer comes down and they discover they’re enslaved.” Being forced to work without pay, under the threat of violence, and unable to walk away surely constitute a form of slavery, and the $40 billion generated by modern slave laborers today is the lowest fraction of the global economy ever generated by slave labor: “Today, we don’t have to win the legal battle; there’s a law against it in every country. We don’t have to win the economic argument; no economy is dependent on slavery (unlike in the 19th century, when whole industries could have collapsed). And we don’t have to win the moral argument; no one is trying to justify it any more.”54 And there’s a freedom dividend: as slaves become legal producers and consumers, local economies spiral upward very rapidly.

These modern antislavery campaigners argue that the criminalization of slavery is important in the abolishment of the continued practice, noting that it is only in countries where slavery has been criminalized—and not just abolished—that the prosecution of slaveholders becomes legally practical. As previously noted, in the African country of Mauritania, for example, slavery wasn’t abolished until 1981, but it was only criminalized in 2007, so now the process of prosecuting slaveholders as criminals has begun, albeit slowly. As the CNN correspondent John Sutter noted in his report on the conditions of the people there, “The first step toward freedom is realizing you’re enslaved.”55

* * *

The rational arguments and scientific refutations of slavery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that led to its legal abolition and universal denunciation set the stage for the other rights revolutions that led to greater justice and freedoms for blacks and minorities, women and children, gays and lesbians, and now even animals, and expanded the moral sphere to include more sentient beings than ever before in human history.