A Moral Science of Animal Rights

When I view all beings not as special creations, but as the lineal descendants of some few beings which lived long before the first bed of the Cambrian system was deposited, they seem to me to become ennobled.

—Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, 18591

Six hundred miles off the coast of Ecuador lies an archipelago called the Galápagos, famous for its connection to Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution by means of natural selection. Darwin spent five weeks there in the fall of 1835, and in 2004 I accompanied my friend and colleague Frank J. Sulloway on his expedition to retrace Darwin’s footsteps.2 The Ecuadorian government has ownership and jurisdiction over the archipelago and it has gone to great lengths to keep the islands as pristine and natural as possible. For example, before we were allowed to hike off trail into the interior of the islands we had to go through a careful quarantine process to ensure that no foreign invaders were hiding in our backpacks or clothes. Nevertheless, invasive species are an ongoing problem for the native populations, especially the famous Galápagos tortoises, whose diet depends heavily on the local vegetation, which has been systematically eroded by goats, introduced almost a century ago and now threatening the tortoises and other species with extinction.

In response, the National Park Service of Ecuador undertook a massive goat eradication project on the most affected island—the massive 58,465-hectare Santiago Island—which resulted in the killing of more than seventy-nine thousand goats in a span of four and a half years in the mid-2000s. The initial culling of the goats was done by riders on horseback, who corralled them into pens with air horns and rifle shots and then killed them. But this method fell far short of the goal because of the brutally harsh terrain of these volcanic islands. It is dry and hot, and the razor-sharp a’a lava surface slices up your hiking boots. Bushwhacking through thorn-festered scrub brush slashes up your arms and legs. Water is hard to come by, so you have to carry your supply on your back. The landscape is undulating and jagged, and there are numerous lava-formed caves, nooks, and crannies in which goats can hide from human hunters. Even though I am in good physical condition from a lifetime of competitive cycling, I found this trek with Frank to be a grueling slog, among the most arduous things I have ever undertaken. Even the native Ecuadorians more acclimated to the equatorial environment had to turn to helicopters to find the remaining goats, shooting them with rifles from the air. And still the goats persisted. To finish the job the National Park Service introduced “Judas goats” and “Mata Hari goats” to find the remaining feral goats and kill them. Judas goats are goats captured from nearby islands and equipped with radio collars and then released on Santiago to lead hunters to their remaining kind in hiding. Mata Hari goats are sterilized female Judas goats chemically induced into long-term estrus so that when released they would tempt male goats who were hunter-shy but female-sure. At a cost of $6.1 million, it was the largest eradication of a mammalian species from an island in history.

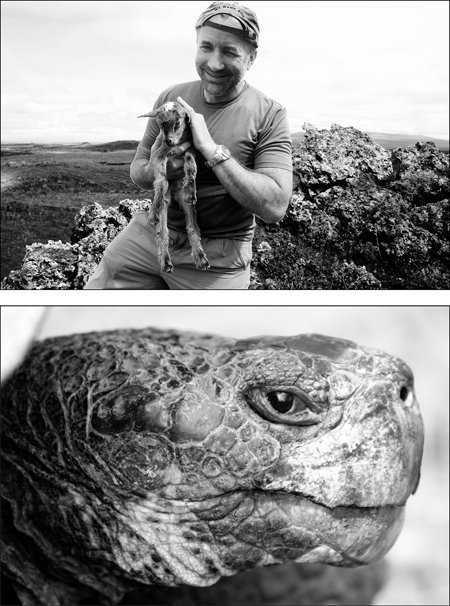

Was this a moral act? Who should live and who should die—the native species that evolved in the Galápagos islands over the course of millions of years, or the goats that were introduced there a mere century ago? At first blush that sounds like a moral no-brainer. The native species have the moral imperative by dint of time. Then again, invasive species have always been a problem for native inhabitants over the course of a billion years of evolution—it is one of the primary causes of extinction in nature—so what we’re talking about here is a difference in time scale (long-term versus short-term) and the source of the invasion (natural versus human). One species nudging out another species by the natural process of migration and competition is morally different from humans introducing a species to, say, clear unwanted (by people) ground cover. So my moral sympathies were with the conservationist eradicators, until I came across a baby goat and held him in my arms (see figure 8-1). These are surely sentient beings, and as mammals they are perhaps even more sentient—more emotional, responsive, perceptive, and with an increased ability to sense and feel—than the ancient reptilian tortoises whose turf they moved in on. But after looking at the cute baby goat, gaze into the eyes of one of these majestic tortoises (also pictured) as they lumber across the landscape in search of vegetation—which they have been doing in this island archipelago for millions of years untouched by civilization—and imagine them extinct because of a bunch of feral goats, and then try to defend the goat’s moral position. Then again, the goats didn’t choose to come here, nor did they arrive by an accident of nature, such as a chance flotilla of debris from a storm that probably brought the tortoises here millions of years ago.

Figure 8-1. A Moral Dilemma in the Galápagos Islands

The author with a baby goat in the Galápagos Islands before she and all other goats were eradicated to save the native Galápagos tortoises (also pictured). Is that moral? Where is the moral bright line? Credit: Author’s collection.

This is a morally dumbfounding problem, and one that well represents others related to animal rights. It’s a moral triage of who lives and who dies. “In the long run, eradication is going to be cheaper,” explained Josh Donlan of Cornell University, who published a paper on the goat-eradication project. “It also makes sense from an ethical perspective, because in the end you are actually killing fewer animals,” referring to all the native individuals who would have died from lack of food and that ultimately would have led to their extinction.3 I concur, but not without some regret for our complicity in the problem in the first place, and acknowledgment that this “return to nature” can only go so far, given the impossibility of implementing such programs in places where civilization has encroached so deeply into nature that there is little natural ecology left. Short of a “world without us” scenario in which every human on Earth suddenly disappears and nature comes roaring back with a vengeance over all of our man-made structures,4 there is no clear reconciliation between animals and civilization, no obvious moral bright line.

Nevertheless, I shall argue that the arc of the moral universe of animals also has bent toward justice, as witnessed by this very act of animal genocide in the name of saving life and preserving nature. Less than a century ago people thought nothing of introducing members of a non-native species into the Galápagos Islands, oblivious to what they might do to the ecosystem. In Darwin’s time it was common for sailing ships to visit the Galápagos to collect tortoises and store them alive in the bowels of the ships and eat them while crossing the Pacific Ocean. Even Darwin—who was ahead of his time on so many social issues (including the abolition of slavery)—ate his tortoise data during HMS Beagle’s voyage home across the Pacific.5

CONTINUOUS THINKING ABOUT ANIMALS

A moral system based on continuous rather than categorical thinking gives us a biological and evolutionary foundation for the expansion of the moral sphere to include nonhuman animals, based on objective criteria of genetic relatedness, cognitive abilities, emotional capacities, moral development, and especially the capacity to feel pain and suffer. This is, in fact, what it means to be a sentient being, and for this reason I worded the first principle of this science-based moral system as the survival and flourishing of sentient beings. But which sentient beings, and which rights?

Instead of thinking of animals in categorical terms of “us” and “them,” we can think in continuous terms from simple to complex, from less to more intelligent, from less to more aware and self-aware, and especially from less to more sentient. So, for example, if we place humans at 1.0 as a full-rights-bearing sentient species, we could classify gorillas and chimps at 0.9; whales, dolphins, and porpoises at 0.85; monkeys and marine mammals at 0.8; elephants, dogs, and pigs at 0.75; and so forth down the phylogenetic scale. Continuity, not categories.6 Take brains, for instance. Scaling average brain size across species we can compare the brains of gorillas (500 cubic centimeters, or cc), chimpanzees (400cc), bonobos (340cc), and orangutans (335cc) with those of humans at an average of 1,200–1,400cc. Dolphin brains are especially noteworthy, coming in at an average of 1,500–1,700cc, and the surface area of a dolphin’s cortex—where the higher centers of learning, memory, and cognition are located—is an impressive 3,700cc2 compared to our 2,300cc.2 And although the thickness of the dolphin’s cortex is roughly half that of humans, when absolute cortical material is compared, dolphins still average an impressive 560cc compared to that of humans at 660cc.7

These notable facts about dolphins led a scientist named John C. Lilly to found the semi-secret “Order of the Dolphin” in 1961, a veritable who’s who of scientists that included the astronomer Carl Sagan and the evolutionary biologist J. B. S. Haldane, both of whom were interested in communicating with extraterrestrial intelligences. Since ETs were nowhere to be found, dolphins would serve as a terrestrial stand-in on how to communicate with a species radically different from us. The research project didn’t pan out, and Lilly’s lack of rigor in his experiments discouraged Sagan and the others from drawing definitive conclusions about dolphin language and intelligence (among other things, Lilly gave his aquatic charges LSD to see if that might open up the doors of perception for them). However, half a century of more scientific research on dolphins since then is revealing. In her book The Dolphin in the Mirror, the psychologist Diana Reiss shows how dolphins pass a modified mirror test of self-awareness.8 For example, a YouTube video of dolphins preening in front of a giant mirror placed in their tank is not just amusing to watch; they clearly know it is themselves they are seeing in the mirror, and they look more than a little pleased with what they see, staring inside their mouths, flipping upside down, blowing air bubbles, etc. This particular video also shows both dolphins and elephants passing the equivalent of the red-dot self-recognition mirror test—the dolphin with an ink mark on his side that he stares at in a mirror (compared to controls who received no mark and did not mirror-stare), and an elephant with an “X” marked on her temple, which, in viewing in a mirror, she touches repeatedly with the tip of her trunk, obviously curious (and perhaps irritated) at its presence.9 As for dolphin language, however, the psychologist Justin Gregg is less enthusiastic than Lilly was in his assessment of the literature, in his book Are Dolphins Really Smart?:

Evidence for a dolphin language—dolphinese—is all but nonexistent. Dolphins do possess signature whistles, which function a bit like names. They likely use them to label themselves and might even call one another’s name on occasion. This is both unique and impressive, but it is the only label-like aspect of dolphin communication that we’ve found. All the other clicks and whistles that dolphins produce are probably used to convey messages about their emotional states or intentions—not the type of complex or semantically rich information found in human language.10

Gregg points out the obvious contradiction in the argument that big brains equal big intelligence: “If big brains are the key to intelligence, why do crows and ravens, which are (literally) bird-brained, display forms of cognition that rival those of their big-brained dolphin and primate cousins. The animal kingdom is full of small-brained species that display astonishingly complex and intelligent behavior.”11

As for cognitive continuity, psychologists who tested a gorilla named Koko concluded that she passes the mirror recognition test for self-awareness. (For comparison, more than half of human infants passed the mirror self-recognition test by age eighteen months and 65 percent by age two.12) Koko also passed an “object permanence” test in which she could memorize the location of moved objects. She was also able to figure out that the quantity of a liquid does not change when it is poured into a different-size container, which is considered another cognitive hurdle in the “conservation of liquid.”13 Elephants have also been observed mourning the loss of a fellow family or tribe member. A 2014 study of twenty-six Asian elephants in a Thailand sanctuary found that when individuals feel stressed by snakes, barking dogs, hovering helicopters, or the presence of other hostile elephants (their ears go out, their tail stands erect, and they emit a low-frequency rumble), their mates comforted them by making seemingly sympathetic noises and by touching them with their trunks on their shoulders, in their mouths, and on their genitals (not recommended in human populations).14

The University of St. Andrews cognitive neuroscientists Anna Smet and Richard Byrne, in a series of clever experiments involving hungry elephants, hid food under an opaque container near an empty container and then pointed to the one where the morsels were located. To their astonishment they discovered that African elephants are the first nondomesticated species who exhibit such advanced social cognition as the ability to read human nonverbal communication. As they noted in their 2013 paper: “Elephants successfully interpreted pointing when the experimenter’s proximity to the hiding place was varied and when the ostensive pointing gesture was visually subtle, suggesting that they understood the experimenter’s communicative intent.”15

This is surprising because previous research found that domesticated animals such as dogs are better at reading nonverbal cues from humans about hidden food (the experimenter simply points to where the food is) than free-living (wild) animals such as chimpanzees, even though the latter are more closely related to us. The prevailing assumption has been that the ability to read human cues evolved in species under domestication as an adaptive strategy for survival. As Smet and Byrne noted, “Most other animals do not point, nor do they understand pointing when others do it. Even our closest relatives, the great apes, typically fail to understand pointing when it’s done for them by human carers; in contrast, the domestic dog, adapted to working with humans over many thousands of years and sometimes selectively bred to follow pointing, is able to follow human pointing—a skill the dogs probably learn from repeated, one-to-one interactions with their owners.”16

But elephants have never been completely domesticated despite repeated attempts over the millennia (dating back at least four thousand to eight thousand years), and regardless of the considerable time spent in captivity in zoos and circuses. The explanation must come from elsewhere. “The African elephant’s complex society makes it a good candidate for using others’ knowledge: its elaborate fission-fusion society is one of the most extensive of any mammal, and cognitive sophistication is known to correlate with the complexity of a species’ social group,” the authors explain. “We suggest that the most plausible account of our elephants’ ability to interpret even subtle human pointing gestures as communicative is that human pointing, as we presented it, taps into elephants’ natural communication system. If so, then interpreting movements of other elephants as deictic [context-dependent] communication must be a natural part of social interaction in wild herds; specifically, we suggest that the functional equivalent of pointing might take the form of referential indication with the trunk.”17

Dogs, of course, are hypersensitive to human cues, and for good reason, since we now know that all modern dogs evolved out of a population of wolves some 18,800 to 32,100 years ago, surviving on the margins of hunter-gatherer bands and coevolving with their human counterparts by learning to read one another’s cues, both verbal and nonverbal.18 The UCLA evolutionary biologist Robert Wayne, lead author of this study, speculated, “Their initial interactions were probably at arm’s length, as these were large, aggressive carnivores. Eventually, though, wolves entered the human niche. Maybe they even assisted humans in locating prey, or deterred other carnivores from interfering with the hunting activities of humans.”19 In addition to dogs’ skulls, jaws, and teeth becoming smaller as they became domesticated, they evolved a set of social-cognitive tools that enabled them to read human communicative signals indicating the location of hidden food. In experimental conditions, domesticated dogs are capable of selecting the right container of concealed food when the experimenter looked at, tapped, or pointed to it, whereas wolves, chimpanzees, and other primates were unable to do so.20

What are dogs thinking when they are interacting with people? Dog owners everywhere have been wondering about this for ages—I’ve had dogs my entire life and can attest that you can’t help but speculate on what is going on behind those curious eyes. To answer this question scientifically the cognitive psychologist Gregory Berns and his colleagues Andrew Brooks and Mark Spivak trained dogs to lie perfectly still inside an MRI brain scanning machine while they presented their canine subjects with human hand signals that indicated the presence or absence of a food reward.21 What Berns and his colleagues saw was the dogs’ caudate nucleus light up in anticipation of a food reward, which is significant because the caudate is rich in dopaminergic neurons—or nerve cells that produce dopamine, which is associated with learning, reinforcement, and even pleasure. When an animal (including a human animal) is reinforced for doing something (a rat pressing a bar or a human pulling a slot machine lever), these neurons release dopamine, which produces a sensation of pleasure, which is a signal to tell the animal to “do that again” (and thus the astonishing success of Las Vegas casinos).

In Berns’s experiments, not only did the scientists see an increase in canine caudate activity in response to hand signals indicating food, “the caudate also activated to the smells of familiar humans. And in preliminary tests, it activated to the return of an owner who had momentarily stepped out of view. Do these findings prove that dogs love us? Not quite. But many of the same things that activate the human caudate, which are associated with positive emotions, also activate the dog caudate. Neuroscientists call this a functional homology, and it may be an indication of canine emotions.”22

In his book-length treatment of his research, How Dogs Love Us, Berns asks “what are dogs thinking?” and answers it this way: “they’re thinking about what we’re thinking.” This is called “mind reading,” or “theory of mind,” and it is usually attributed only to humans and a few primates, but as Berns demonstrates, “Dogs are much better than apes at interspecies social cognition. Dogs easily bond with humans, cats, livestock, and pretty much any animal. Monkeys, chimpanzees, and apes will not do this without a lot of training from a young age. And even then, I would never trust an ape.”23 Berns spells out what this type of sentience means for the ethical treatment of animals:

The ability to experience positive emotions, like love and attachment, would mean that dogs have a level of sentience comparable to that of a human child. And this ability suggests a rethinking of how we treat dogs. Dogs have long been considered property. Though the Animal Welfare Act of 1966 and state laws raised the bar for the treatment of animals, they solidified the view that animals are things—objects that can be disposed of as long as reasonable care is taken to minimize their suffering. But now, by using the M.R.I. to push away the limitations of behaviorism, we can no longer hide from the evidence. Dogs, and probably many other animals (especially our closest primate relatives), seem to have emotions just like us. And this means we must reconsider their treatment as property.24

Instead of property, Berns suggests we should consider dogs to be “persons” in a narrow legal definition. “If we went a step further and granted dogs rights of personhood, they would be afforded additional protection against exploitation. Puppy mills, laboratory dogs and dog racing would be banned for violating the basic right of self-determination of a person.”25

Self-determination and personhood are two ethical criteria developed over the centuries in other rights revolutions to break down the barrier between “us” and “them,” and should be applied to the use of animals in scientific research. Although I have long held the use of animals in research to a different moral standard than, say, puppy mills, dog racing tracks, zoos, and the like—because it is done in the name of something I consider noble, science—a documentary film called Project Nim has led me to rethink even this aspect of animal morality.26 Project Nim was initiated and monitored by Columbia University psychologist Herbert Terrace, who wanted to test the (then) controversial theory of the MIT linguist Noam Chomsky that there is an inherited universal grammar basic and unique to humans, by teaching our closest primate cousin American Sign Language (ASL). Terrace, however, did a turnabout, concluding that the signs Nim Chimpsky (a cheeky nod to Noam Chomsky) learned from his human companions and trainers amounted to little more than animal begging, more sophisticated perhaps than Skinner’s rats pressing bars, but in principle not so different from what dogs and cats do to beg for food, be let outside, etc.27

Nim was taken from the arms of his mother at only a few weeks old. As he was the seventh of her children to be so seized, the mother had to be tranquilized and grabbed quickly so she did not accidentally smother her baby, whom she clutched to her chest in motherly love and protection, as she collapsed on the floor. Nim began his childhood in a brownstone apartment in New York’s Upper West Side, surrounded by human siblings in the mildly dysfunctional LaFarge family spearheaded by Stephanie, who breast-fed Nim and, as he got older, allowed him to explore her nakedness even as he put himself between his adopted mother and her poet husband in an Oedipal scene right out of Freud.28 Just as Nim grew into his new family, surrounded by fun-loving human siblings and days filled with games and hugs, Terrace realized that scientists were not going to take him seriously because there was next to no science going on in this free-love home. (According to one of the trainers, there were no lab manuals, no diaries, no data sheets, no recordings of progress, and no one in the family even knew how to sign ASL!) So for a second time in his young life Nim was wrenched from his mother and placed into a more controlled environment in the form of a sprawling home owned by Columbia University. There a string of trainers carefully monitored Nim’s progress in learning ASL, making daily trips to a lab at the university where Terrace could control all intervening variables in a manner not dissimilar to a Skinner box for lab rats.

In due time Nim grew into his teenage years, and as most testosterone-fueled male primates are wont to do, he became more assertive, then aggressive, then potentially dangerous in his evolved propensity to test his fellow primates for hierarchical status in the social pecking order. The problem is that adult chimpanzees are at least twice as strong as humans. In other words, Nim became a threat. As one of the trainers said while pointing to a scar on her arm that required thirty-seven stitches, “You can’t give human nurturing to an animal that could kill you.” After several of these biting incidents that sent trainers and handlers to the hospital, including one woman who had part of her cheek ripped open, Terrace pulled the plug on the experiment and therewith shipped Nim back to the research lab in Oklahoma whence he came. Tranquilized into unconsciousness, Nim went to sleep surrounded by loving human caretakers on a sprawling estate in New York and awoke in a gray-barred sterile steel cage in Oklahoma.

Having never seen another member of his species, Nim was understandably anxious and scared at the sight of grunting, hooting male chimps eager to let the youngster know his place in the social order. As a result, Nim slipped into a deep depression, losing weight and refusing to eat. A year later Terrace visited Nim, who greeted him eagerly and expressed himself in a manner that Terrace described as signaling to get him out of this hellhole. Instead, Terrace took off the next day for home and Nim slid back into a depression. Sometime later he was sold to a pharmaceutical animal-testing laboratory managed by New York University, where hepatitis B vaccinations were foisted on our nearest primate relatives. Footage of a tranquilized chimp being pulled out of and stuffed back into a steel-barred cage barely big enough to turn around in churns one’s stomach.

As an exercise in the principle of interchangeable perspectives, imagine what Nim might have signed in response to this treatment.29 Sadly, there was no Shawshank redemption for Nim. But thanks to films such as this—whose purpose is to draw us into changing perspectives with their subject—we can at least put flowers on his metaphorical grave. Flowers for Nim.

SPECIESISM: THE ARGUMENT

A century of scientific research on animal cognition and emotion reveals a capacity and depth to warrant our moral consideration for how all sentient beings should be treated.30 Jeremy Bentham—considered by scholars to be the patron saint of animal welfare for his inclusion of nonhuman animals in his classic and groundbreaking 1823 work Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation—asked where we should draw the line between humans and animals:

Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?31

Bentham’s observation that an adult horse or dog has cognitive skills beyond those of a young human infant has been turned into a cogent argument for modern-day animal rights advocates. It was on display, for example, in Mark Devries’s 2013 film Speciesism: The Movie, the Los Angeles premiere of which I attended in a theater full of animal advocates who cheered wildly for the film’s avatars, such as the Princeton ethicist Peter Singer, who articulated the argument in the context of vivisection and its abolitionist opponents:

Would the experimenter be prepared to perform his experiment on an orphaned human infant, if that were the only way to save many lives?… If the experimenter is not prepared to use an orphaned human infant, then his readiness to use nonhumans is simple discrimination, since adult apes, cats, mice, and other mammals are more aware of what is happening to them, more self-directing and, so far as we can tell, at least as sensitive to pain, as any human infant. There seems to be no relevant characteristic that human infants possess that adult mammals do not have to the same or a higher degree.32

Critics counter that our superior intelligence, self-awareness, and moral sense add up to make us wholly other from all other animals and thus justify our exploitation of them. But Singer points out that by these criteria humans being in such states as infancy, severe mental retardation, grave physical handicap, or coma would imply that we can exploit them. Since we would not consider wearing or eating such humans, so we should not do the same to animals whose capacities in such categories as intelligence, self-awareness, and moral emotions are equal or superior to many people in these conditions. “Any characteristic of humans that is said to justify this sharp ethical distinction will either be shared by some nonhuman animals or be absent in some humans,” Devries told me in an interview. “Therefore, the presumption that nonhuman animals’ interests are less important than human interests could be merely a prejudice—similar in kind to prejudices against groups of humans such as racism—termed speciesism.”33

The common counter to this argument, associated with the University of Michigan philosopher Carl Cohen, is that even though some humans may lack this or that characteristic (for example, an infant or a comatose adult may lack language), they are the “kind” of species that has language, since that characteristic is vouchsafed to us. Thus, regardless of the particulars of an individual organism, the general traits of a species is what makes them separate by definition, and so speciesism is justified in this sense.34 Devries finds a major flaw in this argument in that whatever the characteristic is (language, tool use, intelligence) that goes into the “kind” that separates species, it is the moral relevance of those characteristics that matters:

Imagine that someone were to argue that what justifies an ethical distinction between humans and nonhuman animals is the fact that only members of the human species are capable of manufacturing green t-shirts. The reason this seems facially absurd is that obviously there is nothing we consider ethically relevant within the species about the ability to manufacture green t-shirts. Now, if we switch the characteristic to something like language, we actually run into the same problem: if there is nothing we consider ethically relevant within the species about the capacity to use language, how does that characteristic become relevant when we are attempting to distinguish between species? Again, this seems to expose the “kind” argument as simply begging the question by assuming that there is something ethically relevant about species membership.35

As Virginia Morell writes in her thoughtful book Animal Wise, the question “what makes us different?” is the wrong question: “Instead, given that we now know that we live in a world of sentient beings, not one of stimulus-response machines, we need to ask, how should we treat these other emotional, thinking creatures?”36

What about eating animals? Given the fact that we bring into existence animals who would not otherwise have even been born, as long as we give them a decent life while they are alive and end their lives humanely, isn’t this morally acceptable? Temple Grandin makes this point in her books and talks, and she has done much (and should be commended) to reform the factory farm system to make the life of animals more humane.37 And yet, as Mark Devries notes, “in the case of bringing an animal into a life of suffering, that animal is harmed by his or her experiences, whereas the nonexistent animal does not ‘mind,’ since he or she never exists, and thus has no experience of a lack of benefits.” As well, “using animals as economic commodities—bought and sold like property, and brought into existence and killed solely for the purpose of a palate preference—seems obviously inconsistent with taking their interests seriously, just as would be the case if we were doing the same to humans.”38 This is similar to the point I made in the previous chapter on slavery, in which I noted how whites used a similar line of reasoning to justify slavery in arguing that blacks on a plantation have a better life than blacks in Africa (or even blacks and poor whites toiling in factories in Northern states), and that blacks born into slavery in America would not have been born at all otherwise. That may be, but in the long run freedom is better than slavery, and liberty is preferred over oppression.

Michael Pollan, author of the best-selling books The Omnivore’s Dilemma and In Defense of Food,39 points out, “It’s one thing to choose between the chimp and the retarded child or to accept the sacrifice of all those pigs surgeons practiced on to develop heart-bypass surgery. But what happens when the choice is between ‘a lifetime of suffering for a nonhuman animal and the gastronomic preference of a human being’? You look away—or you stop eating animals. And if you don’t want to do either?” Like most of us, Pollan doesn’t want to do either, and so employs a favorite cognitive tool we all use: denial. Nevertheless, even an omnivore such as Pollan can marshal counterarguments to his own beliefs like a skilled rhetorician, citing the book Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy by the Christian conservative author Matthew Scully, who believes God commands us to “treat them with kindness, not because they have rights or power or some claim to equality but … because they stand unequal and powerless before us.”40 Pollan’s description (drawn from Scully’s work) of how pigs—who are as smart as dogs—are treated has to shudder even the hardiest of bacon-, ham-, and pork-eating omnivores:

Piglets in confinement operations are weaned from their mothers 10 days after birth (compared with 13 weeks in nature) because they gain weight faster on their hormone- and antibiotic-fortified feed. This premature weaning leaves the pigs with a lifelong craving to suck and chew, a desire they gratify in confinement by biting the tail of the animal in front of them. A normal pig would fight off his molester, but a demoralized pig has stopped caring. “Learned helplessness” is the psychological term, and it’s not uncommon in confinement operations, where tens of thousands of hogs spend their entire lives ignorant of sunshine or earth or straw, crowded together beneath a metal roof upon metal slats suspended over a manure pit. So it’s not surprising that an animal as sensitive and intelligent as a pig would get depressed, and a depressed pig will allow his tail to be chewed on to the point of infection. Sick pigs, being underperforming “production units,” are clubbed to death on the spot. The U.S.D.A.’s recommended solution to the problem is called “tail docking.” Using a pair of pliers (and no anesthetic), most but not all of the tail is snipped off. Why the little stump? Because the whole point of the exercise is not to remove the object of tail-biting so much as to render it more sensitive. Now, a bite on the tail is so painful that even the most demoralized pig will mount a struggle to avoid it.41

Scully, whose conservative credentials include working as special assistant and senior speechwriter for President George W. Bush, makes the case for animal rights as well as anyone in the secular/liberal axis, and he does so by employing a natural rights argument devoid of any supernatural special pleading or holy book injunction:

If natural law is what informs our own laws and moral codes among one another, in short, then it should also inform our laws and moral codes regarding animals. And its most basic and revolutionary insight is the same for them as for us. Any moral claims we have, we have simply because of what we are. Any moral claims that animals have in relation to us, they, too, have simply because of what they are. We don’t each get to decide their moral claims for ourselves. The moral value of any creature belongs to that creature, acknowledged or not, a different value from our own but just as much a hard and living reality. Just as our own individual moral worth does not hinge on the opinion of others, their moral worth does not hinge upon our estimation of them.42

Another argument for why an animal’s place is in our stomach is because in nature an animal’s place is in each other’s stomachs. Animals eat each other, and since we’re animals who also need to eat, isn’t it natural we should eat them? This is not a bad rejoinder, although animal rights advocates counter that throughout human history slavery, genocide, and rape were considered natural and the ways things were always done, and yet we outlawed them as immoral. We all have an evolved nature for a certain amount of violence—self-defense, jealousy, honor—yet that does not mean we should not try to control our impulses. The point of morality is to choose to do what you might otherwise not have done. You can seek your own survival and flourishing with no one else’s survival and flourishing in mind, but when you take the perspective of other sentient beings into consideration, that is what makes it a moral act.

ANIMAL ARBEIT MACHT FREI

At this point I have a confession to make: I am a speciesist—I eat and wear members of other species. There are few foods I find more pleasurable than a lean cut of meat—a tri-tip, a tuna or salmon steak, a buffalo burger. And I laughed out loud at the joke about the farmer who castrates his horse with two bricks, who when asked if it hurts replied, “Not if you keep your thumbs out of the way.”43 I also find disturbing those on the edges of the animal liberationist movement who trash or destroy scientific laboratories and release lab animals. I caution them (contra Barry Goldwater) to consider that moderation in the pursuit of liberty is no vice, and extremism in the defense of justice is no virtue.44

Also, in my opinion, context and motivation matter. There is a tiny Inuit community in Gambell, Alaska, whose livelihood of killing walruses has been severely curtailed because of the ice breakup due to global warming. There are 690 residents who killed “only” 108 walruses this year, which is one-sixth the average of their annual kill rate of 648 walruses. A thirty-eight-year-old resident of Gambell named Jennifer Campbell, a mother of five whose family depends on walrus meat, bemoaned the fact that they caught only two walruses this year, compared to the average of twenty in normal years. “If it continues like this, we will seriously starve,” she said.45 It seems to me that there is a sizable moral difference between some Beverly Hills diva wearing a fur to a trendy LA restaurant where you’ll down a juicy steak when you could have ordered the veggie burger, and the Inuit inhabitants of Gambell, Alaska, who kill and eat and use walruses for their survival. Here we encounter moral dumbfounding: once you concede that speciesism exists and we breach the barrier, wouldn’t all killing of animals be the same regardless of context and motivation? But clearly there is a contextual and motivational difference between these two scenarios, and that difference matters morally.

I am also troubled by an affecting analogy running throughout the animal rights movement (and on graphic display in many documentary films such as Earthlings and Devries’s Speciesism: The Movie) that animals are undergoing a “holocaust,” made poignant by the architectural layout comparison between factory farm buildings and prisoner barracks at the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau—row on row of long, rectangular buildings surrounded by barbed-wire fences. Worse, goes the analogy, as evil as the Holocaust was in its attempt to exterminate groups of people, in factory farming new generations of sentient beings are brought into existence only to be exterminated, again and again, generation after generation. Some animal rights activists refer to this as a Holocaust that never ends, captured in the book title Eternal Treblinka by Charles Patterson,46 taken from the Yiddish writer and Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer, a vegetarian who famously wrote (through one of his fictional characters):

In his thoughts, Herman spoke a eulogy for the mouse who had shared a portion of her life with him and who, because of him, had left this earth. “What do they know—all these scholars, all these philosophers, all the leaders of the world—about such as you? They have convinced themselves that man, the worst transgressor of all the species, is the crown of creation. All other creatures were created merely to provide him with food, pelts, to be tormented, exterminated. In relation to them, all people are Nazis; for the animals it is an eternal Treblinka.”47

One limitation of this analogy is in the motivation of the perpetrators. As someone who has written a book on the Holocaust (Denying History48) I see a vast moral gulf between farmers working to feed the world and turning a profit in so doing, and Nazis with a genocidal motive. Small-farmers who kill animals in the service of making a living by providing food to people who want and need it bear no motivational resemblance to SS guards murdering Jews, Gypsies, and homosexuals for the sole purpose of “racial cleansing” and “eliminationist purity.” Even corporate factory farmers motivated solely by quarterly profits and who care not at all for the welfare of their animals, whom they consider to be nothing more than products, are higher on the moral ladder than Adolf Eichmann and Heinrich Himmler and their henchmen, who orchestrated the processing of mass murder on an industrial scale. There are no signs at factory farms reading “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Makes You Free”).

Yet I cannot fully rebuke those who equate factory farms with concentration camps when I recall one of the most dreadful things I ever had to do. While working as a graduate student in an experimental psychology animal lab in 1978 at California State University at Fullerton, it was my job to dispose of lab rats who had outlived our experiments. This was not a pleasant task, made all the worse by the fact that we named our rats after the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team of that era—Ron Cey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell, Steve Garvey, Don Sutton, and the rest. You get to know your lab animals, and they get to know you. But then the experiment is over and the time comes to dispose of the subjects, which in the case of the rats was done by … I can barely type the words … gassing them with chloroform in a large plastic trash bag. I wanted (and asked) if I could take them up into the local hills and let them go, figuring that death by predation or starvation was surely better than this. But my suggestion was rejected in no uncertain terms because what I was proposing was actually illegal. So I exterminated them. With gas. The very words used to describe this act—exterminating a group of sentient beings by gassing them—are uncomfortably close to those I wrote in my Holocaust book to describe what the Nazis did to their captives. No wonder naming your lab animals is considered taboo in science. I thought it was to encourage objectivity, but I now suspect that it has as much to do with remaining emotionally detached so as to feel morally blameless.

Today the treatment of lab animals is less loathsome, and according to my old professor Douglas Navarick—whose lab at Cal State Fullerton I worked in for those two years and whom I recently queried to confirm my memory of the process at the time—the method now used is “metered CO2” for rats. He adds, “There is now a committee on campus that reviews and must approve any research or instructional activity involving vertebrate animals (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) and it has rules for what type of euthanasia should be used for different species (I’m a member).”49 This is certainly an improvement over what I did (and what was customary at the time in animal labs everywhere), and it is good to know that animal care committees have also become sensitive to the effects on the animals’ human caretakers, as instructed in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: “Euthanizing animals is psychologically difficult for some animal care, veterinary, and research personnel, particularly if they perform euthanasia repetitively or are emotionally attached to the animals being euthanized. When delegating euthanasia responsibilities, supervisors should be sensitive to this issue.”50

This counts as moral progress, to be sure, but I remain deeply unsettled both by what I did and the perspective of the guidebook, which still sounds more concerned with the welfare of the perpetrators than the victims, whereas the long-term trend is to shift moral perspectives from the former to the latter.

PERSPECTIVE-TAKING

Perspective-taking is the psychological foundation underlying the capacity for empathy. To judge the rightness or wrongness of an action against another, one must first take the perspective of that other sentient being. In the context of animal rights, I am reminded of the scene in the film My Cousin Vinny, in which Joe Pesci’s character, Vinny Gambini, is preparing to go deer hunting with the opposing attorney in their court case to ascertain what his strategy in the trial might be through the anticipated camaraderie of a hunt. As he is getting dressed to go he inquires of his fiancée—Marisa Tomei’s character, Mona Lisa Vito—if the pants he has on are appropriate for deer hunting. She answers with a thought experiment in perspective-taking:

Imagine you’re a deer. You’re prancing along. You get thirsty. You spot a little brook. You put your little deer lips down to the cool, clear water. Bam! A fuckin’ bullet rips off part of your head. Your brains are layin’ on the ground in little bloody pieces. Now I asks ya, would you give a fuck what kind of pants the son of a bitch who shot you was wearing?51

Perspective-taking is what animal rights documentarians are trying to evoke in those hidden-camera videos of slaughterhouses and the horrific conditions in which factory farm animals live (or, more to the point, suffer and die). In a short video clip posted at freefromharm.com and appropriately titled “saddest slaughterhouse footage ever” (to see it, Google-search that word string), a bull is waiting in line to die. As he hears his mates in front of him being killed he shakily backs up into the rear wall of the metal chute. When he can go no farther, he turns toward the back (from where the camera is filming) as if looking to escape his fate. A worker walks along the outside of the chute with an electric cattle prod and zaps the bull forward. He takes a few hesitating steps, stops, and starts to back up again, so the worker jolts him with some more electricity far enough forward for the final death wall to come down behind him. You see his rear legs trying one last time to back up out of his death trap and then … thump!… down he goes in a heap, rear legs poking out of the slot at the bottom of the wall. Dead.52 Am I projecting human emotions into the head of a cow? I don’t think so. The investigative journalist Ted Conover, while working undercover as a USDA inspector at the Cargill Meat Solutions plant in Schuyler, Nebraska, when he asked a worker there why the ramps leading the animals up to the killing chamber stank so bad from cattle waste, was told, “They’re scared. They don’t want to die.”53 Perhaps this is why many factory farms have barbed wire surrounding their facilities and they do not take kindly to snooping documentary filmmakers probing around with their cameras.

The 2005 film Earthlings is arguably the most disturbing of the perspective-taking documentaries, drawing parallels between the mistreatment and economic exploitation of blacks and women in centuries past with the maltreatment and commercial use and abuse of animals today.54 To describe the film as hard to watch is an understatement. To get through it I had to have two windows open on my computer screen: the film and the transcript of it for note-taking purposes, which was really just a pretext to cover the gore when I could take it no more. Scenes of animals being processed as products include slashed-open dolphins flopping around on a concrete floor while schoolchildren obliviously pass by, and cattle being killed by a captive bolt gun that fires a steel bolt in the animal’s brain by compressed air, a process that doesn’t always work, leaving them struggling for life even as the butchering process begins. Such images are overlaid with narration to drill home the point not just of our evolutionary continuity with all other animals, but of their continuity with us:

Undoubtedly there are differences, since humans and animals are not the same in all respects. But the question of sameness wears another face. Granted, these animals do not have all the desires we humans have; granted, they do not comprehend everything we humans comprehend; nevertheless, we and they do have some of the same desires and do comprehend some of the same things. The desires for food and water, shelter and companionship, freedom of movement and avoidance of pain. These desires are shared by nonhuman animals and human beings.55

Perhaps the windowless, fortresslike factor of farm buildings surrounded by barbed-wire fences is a two-way agreement—most of us don’t want to know how sausage is made. As the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson poignantly observed, “You have dined, and however scrupulously the slaughterhouse is concealed in the graceful distance of miles, there is complicity.”56

The power of visual media to shift our perspective-taking is on disturbing display in the Academy Award–winning 2009 documentary film The Cove, about the mass slaughter of dolphins and porpoises in Taiji Cove in Wakayama, Japan. The film features Ric O’Barry, former dolphin trainer for the 1960s hit television series Flipper, which as a young boy I watched faithfully every week as the show highlighted the very humanlike characteristics of these marine mammals, most notably their humanity in social bonding with each other and with humans (and in which each week Flipper predictably thwarted bad guys in their nefarious activities underwater or rescued good guys trapped in improbable circumstances). According to the film, dolphins are herded into the cove, where a few are captured unharmed for sale to marine parks and aquariums around the world, while the rest are brutally butchered and killed for their meat, which is sold to resalers in Japanese fish markets. The press attention the film received after it won the Academy Award led to Japanese government officials scrambling to deny, then explain, and then rationalize away the ruthless butchery of sentient beings so close to us in social cognition and emotion as to wrench powerful emotions at the sight of their slaughter.

One heart-ripping scene among many captured on film (with cameras hidden inside rocks and long-range lenses from the surrounding hills) is that of a young dolphin desperately trying to survive after being slashed open, gasping for air as blood gushes out of her torso, crying for help as the filmmakers watch in horror, powerless to save her as she slips beneath the surface one final time in a pool of blood, never seen again. It is at once an infuriating and sickening scene to watch. I cannot say that I would have been able to restrain myself from jumping into the cove, swimming over to the cluster of tiny boats, and in Rambo-like fashion pulling these fishermen into the water and giving them a dose of their own machete-medicine. But no matter how powerful the temptation for retaliatory violence in these circumstances, such vigilante justice is precisely what most animal rights activists avoid; you can’t be an effective rights activist if you are in jail.

O’Barry and his crew showed great restraint in not attempting to stop the slaughter and instead expose it to the world through such gut-wrenching scenes, and that’s the point of the film—it translates the abstract into the concrete, thereby engaging our brain’s empathic neural pathways that are normally triggered when experiencing another human’s pain. So, even more than our shared intelligence, self-awareness, cognition, and moral capacity, it is our common capacity to suffer in a very human way—gasping for air, struggling to stay upright, fighting for life—that, in part, expands the moral sphere. Animal rights will not be fully realized until we gain a deep emotional understanding that they are sentient beings who—like us—want to live and are afraid to die.

This is where is becomes ought, where the way things are naturally—by nature animals desire food, water, shelter, companionship, freedom of movement, avoidance of pain just like we do—becomes the way things ought to be, especially when a departure from nature is the result of an exploitation of one animal species over another. Here we make a moral choice in which perspective-taking reverses the naturalism argument—from the perspective of humans exploiting animals to fulfill our nature, to the perspective of animals fulfilling theirs. Moral progress has been driven primarily by this shift in perspective-taking, from the exploiter to the exploited, from the perpetrator to the victim. Why should we favor one perspective over the other? Because that is how moral progress is made.57

FIRST, DO NO HARM

In the animal rights debate there is a counterargument put forth by the philosopher Daniel Dennett in his book Kinds of Minds, in which he draws a distinction between pain and suffering, suggesting that the former is more visceral and basic and shared by most animals, while the latter involves more humanlike emotions such as worry, shame, sadness, humiliation, dread, and especially anxiety from projecting what may happen in the future, which requires higher cognitive functioning shared by only a few animals. “If we fail to find suffering in the animal lives we can see, we can rest assured there is no invisible suffering somewhere in their brains. If we find suffering, we will recognize it without difficulty.”58 I’m not so sure. In all these films and videos of animals in pain and suffering, it looks to me that they are anxious, worried, and fearful. Furthermore, why should we assume that animals suffer less than humans? If the argument is that we can’t really know what goes on inside the minds of other sentient beings, why assume that their suffering is less than ours? Maybe it’s worse for other animals.

A moral foundation for animal rights begins with how we treat them, a good starting point of which may be found in the Hippocratic Oath’s ethical precept primum, non nocere—first, do no harm. “All ethical theories and moral systems appear to share the basic principle that, all else being equal, causing harm—specifically suffering—is a bad thing,” the filmmaker Mark Devries told me. “Because nonhuman animals are capable of experiencing suffering, this basic ethical principle prima facie applies beyond the species barrier.” As in my moral model, sentience is key to Devries’s reasoning: “If an animal’s capacity to have a subjective experience of harm is the ethically relevant characteristic, then the proper ‘cutoff point’ for what species must be considered appears to turn on whether the animals are sentient. We know that birds and mammals are capable of physical and emotional suffering, in fact the neural anatomy that permits such experiences in humans was developed in our common ancestors with those animals.”59

It is especially in the area of animal rights that we must remember that it is the individual who is the moral agent—not the species—because it is the individual organism who feels pain and suffers. Or to be more precise, it is an individual brain with the ability to feel pain that constitutes an individual organism. It is an individual bull who walks through the chute into the entrapment and faces the captive bolt gun, not the species Bos primigenius. It is an individual dolphin who is sliced open in a cove in Japan who gushes blood and gasps for air, not the species Delphinus capensis.

A PROFOUND SHIFT IN MORAL PERCEPTION

Although the parallels between the human and animal rights movements are abundant, it seems to me the latter have a significantly larger task than the slavery abolitionists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did, given that even at the zenith of the slave trade only a small portion of the world’s population owned or traded in slaves, whereas the vast majority of the world’s population eats meat and uses animal products. As the animal rights attorney Steven Wise notes, animals are even more essential to our daily lives than slaves were in nineteenth-century America—including personally, psychologically, economically, religiously, and especially legally, where animals are property and their use protected by law, which is not always easy to change.60 Even if the arguments in favor of animal rights are better than those opposing them—which I think they are—bumping up the percentage of the population committed to a vegetarian or vegan lifestyle from the low single digits into the high double digits is going to be a daunting task. People didn’t have to own slaves to survive. But people do have to eat, and meat is delicious to most, relatively cheap, and readily available, and therefore (still) a popular commodity to fulfill that need. In the United States it took a civil war to finally abolish slavery, and that was with only a small fraction of citizens owning slaves. When more than 95 percent of the population eats meat, that’s a daunting difference.

To bring about significant change we are going to need the equivalent of what the slavery historian David Brion Davis calls “a profound shift in moral perception,”61 a reconfiguration in how we think about animals, from property to persons, as the Rutgers University legal scholar Gary Francione has done in his 2008 book Animals as Persons, where he outlined in logical detail why sentient nonhumans should legally be regarded as persons: “They are conscious; they are subjectively aware; they have interests; they can suffer. No characteristic other than sentience is required for personhood.”62

Moral progress along these lines occurred in 2013 in India, which banned the captivity of dolphins for public entertainment because “Confinement in captivity can seriously compromise the welfare and survival of all types of cetaceans by altering their behavior and causing extreme distress.” Putting teeth into the law, India listed all cetacean species in Schedule II, Part I of the Wild Life Protection Act of 1972, adding that dolphins should be considered as “nonhuman persons.”63 This granting of legal personhood to a nonhuman animal is a monumental step toward justice and freedom for all sentient beings.

Reading the works of animal rights activists can be an emotionally draining experience, and if we focus only on the worst cases (factory farms) and raw numbers killed (in the Hemoclysm billions, not Holocaust millions), a case could be made that the arc of the moral universe is decidedly bent backward. So it is good to reflect on how people used to perceive animals, from the recreational (cat burning and bear baiting) to the philosophical (Descartes’s belief that animals are mechanical automata who merely mimicked pain, pleasure, desire, interest, boredom, and the rest of humanlike emotions he denied animals could experience). A sizable body of literature exists that tracks the mixed (although mostly bad) moral history of animal welfare over the millennia.

As with the abolition of slavery, religion not only did not lead the revolution for animal welfare, it often hindered it, starting at the beginning … literally in the first chapter of Genesis when Yahweh commands Adam and Eve to “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”64 The attitude was reinforced over the centuries by such church fathers as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, the latter of whom opined, “Hereby is refuted the error of those who said it is sinful for a man to kill dumb animals: for by divine providence they are intended for man’s use in the natural order. Hence it is not wrong for man to make use of them, either by killing or in any other way whatever.” Apparently Aquinas must have gotten some push-back from those who felt sympathy with suffering animals, for he followed the above observation with this admonition: “And if any passages of Holy Writ seem to forbid us to be cruel to dumb animals, for instance to kill a bird with its young: this is either to remove man’s thoughts from being cruel to other men, and lest through being cruel to animals one become cruel to human beings: or because injury to an animal leads to the temporal hurt of man, either of the doer of the deed, or of another.”65

Ever since biblical times, animal cruelty was the norm, not the exception. Cockfights and dogfights, of course, have been a perennial favorite across the centuries, and in Colonial America bear baiting featured a captured bear chained to a post, where she would be tormented (baited) and even ripped to shreds by dogs who were whipped up into an attack frenzy. And who could forget the sixteenth-century popular Parisian pastime of cat burning, in which a terrified feline was gradually lowered into a fire while “spectators, including kings and queens, shrieked with laughter as the animals, howling with pain, were singed, roasted, and finally carbonized.” Or the fun of nailing a cat to a post and having a contest to see who could head-butt it to death without getting one’s eyes clawed out by the horrified beast.66

But that’s just recreational cruelty. Food production brutality does not begin with the factory farms of today. Consider this account of a practice common in the seventeenth century quoted by the historian Colin Spencer in his sweeping history of vegetarianism, The Heretic’s Feast, of the slaughter of animals and the extent to which anyone cared much for their experience of the process:

Methods of slaughter were coldly rational. As Dr. Johnson remarked, the butchers “have no view to the ease of the animals but only to make them quiet for their own safety and convenience.” Cattle were poleaxed [knocked out] before being killed, but pigs, calves and poultry died more slowly. In order to make their meat white, calves and sometimes lambs were struck in the neck so that the blood would run out. Then the wound was stopped and the animal allowed to linger on for another day. As Thomas Hardy’s Arabella explained to Jude, pigs should not be slaughtered quickly. “The meat must be well bled and to do that he must die slow. I was brought up to it and I know. Every good butcher keeps them bleeding long. He ought to be up till eight or ten minutes dying at least.”67

THE MORAL ARC IS BENDING FOR ANIMALS

Moral progress has been sporadic and halting, to be sure, but the arc has been bending ever so slightly for animals ever since the Enlightenment, as we have already seen in the case of the treatment of laboratory animals over the past several decades, the shift in perspective-taking that has been under way for a century as we come to understand the continuity between ourselves and other animals, and the linking of the animal rights movement to other rights revolutions whose success has raised the moral consciousness of everyone to expand the moral sphere even wider to include at least some animals.

A 2003 Gallup poll, for example, found that “The vast majority of Americans say animals deserve at least some protection from harm and exploitation, and a quarter say animals deserve the same protection as human beings.” Bans on medical research and product testing were still opposed by most Americans, and even though the percentage of households with hunters has dropped from about 30 percent to about 20 percent in the past quarter century, most Americans oppose banning all types of hunting. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to know that “96% of Americans say that animals deserve at least some protection from harm and exploitation, while just 3% say animals don’t need protection ‘since they are just animals.’” Most notably, 25 percent of all Americans say that animals deserve “the exact same rights as people to be free from harm and exploitation.”68

This is noteworthy because rights talk gets fuzzy when it comes to positive rights about what people (or sentient beings) deserve to have, with much dispute even over what humans are entitled to (health care, Social Security, disability insurance, and the like). But being free from harm and exploitation involves only the cessation of a negative activity (the inducement of pain and suffering). For example, in the Gallup poll, sixty-two percent of “Americans support passing strict laws concerning the treatment of farm animals.”69

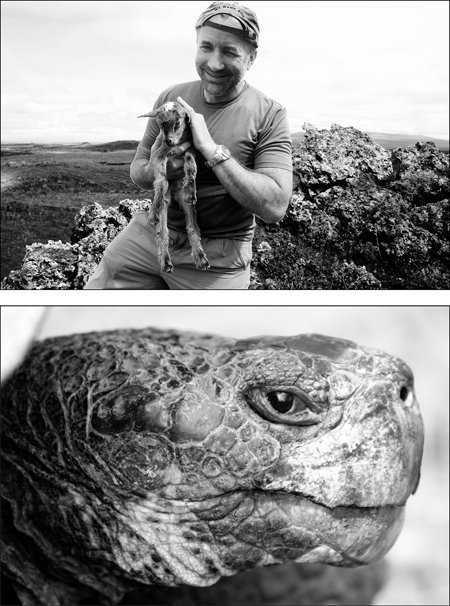

As for the consumption of animals as food, in 2012 the Vegetarian Resource Group commissioned the National Harris polling agency to ask, “How Often Do Americans Eat Vegetarian Meals?” and “How many adults in the U.S. are vegetarian?” (meaning no meat, fish, seafood, or poultry). Results: 4 percent of Americans always eat vegetarian meals, of which 1 percent are always vegan (also no dairy or eggs) and 3 percent are always vegetarian. On the more moderate side, 15 percent eat “many” of their meals vegetarian (but less than half the time), while another 14 percent make half or more (but not all) of their meals vegetarian, with almost half (47 percent) having eaten vegetarian meals at some point during the year (a dubious statistic, since a bowl of granola would count as a vegetarian meal).70 A 2012 Gallup poll was slightly more encouraging, with a total of 2 percent vegan and 5 percent vegetarian.71 I suspect the differences are in the statistical noise, with the overall numbers so low. Still, over the past several decades the trend line is unmistakably upward, as seen in figure 8-2.

Another trend encouraging to animal welfare proponents is a recent downward turn in meat consumption and a resulting drop in the number of animals raised for food. This appears to be largely the result of a rise in people adopting modest hybrid eating habits, such as “flexitarians” (flexible vegetarians) who, for example, practice “Meatless Mondays” or are “vegan until 6:00 p.m.” or who eat red meat only once a week, and the like. According to the USDA, for example, between 2007 and 2012 meat and poultry consumption dropped by 12.2 percent.73 It’s not a huge number, but it’s not trivial either. Slightly more encouraging are the figures for semi-vegetarians, defined as people who eat meat for less than half their meals, which, according to the Humane Research Council, ranges from 12 percent to 16 percent of the US population. Still larger are the percentages of “active meat reducers,” or “those who say they eat less meat compared to one year ago,” which is 22 to 26 percent of the US population, or roughly a quarter, which is indeed nontrivial.74

Figure 8-2. Trends in Vegetarianism

The gains are modest but upward.72

Ever since World War II, European countries have shifted politically more leftward than America, and this has expanded more extensively the moral sphere for animals there. In a number of European countries sows (female pigs) may not be confined to crates so small that they cannot turn around, and hens must be in cages large enough to stretch their wings. In England, the farming of animals for fur is now illegal. Switzerland has changed the status of animals to “beings” instead of “things,” and Germany was the first nation to grant animals a constitutional right when they added the words “and animal” to a provision obliging the state to respect and protect human dignity.

Medically, a diet of meat—especially red meat eaten regularly—has proven to be unhealthy and a major contributor to cardiovascular disease in many (but not all) people. Environmentally, factory cattle farms generate massive amounts of waste products and the greenhouse gas methane, among many other pollutants. And they stink to high heaven—I shall never forget riding my bike during the Race Across America through Dalhart, Texas, where the country’s largest cattle ranches are located. You could smell them from miles away. I can’t imagine what the local residents do, other than habituate to the smell to the point where they no longer notice it, which itself could be a metaphor for the overall treatment of animals—we have become habituated to their pain and suffering.

Blood sports such as cockfighting and dogfighting have been banned in most Western democracies, and even bullfighting appears to be on its way out. A 2008 Gallup poll found that almost four in ten Americans say they favor banning sports that involve competition between animals, such as horse racing and dog racing.75 Hunting and fishing are on the decline as well, down 10 to 15 percent from 1996 to 2006, and it is not due to people staying indoors playing video games or watching television, because the percentage of people participating in wildlife watching and ecotourism increased by a corresponding amount over the same time frame.76 According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, in 2011 there were 13.7 million hunters and 33.1 million anglers, but “Almost 68.6 million people wildlife watched around their homes, and 22.5 million people took trips of at least one mile from home to primarily wildlife watch,” which totals 91.1 million.77 That’s a lot of wildlife watching compared to killing.

I have witnessed and made the transition myself over the past several decades—as a youngster in the 1960s my stepfather regularly took my stepbrothers and me out to hunt dove and quail. I did not enjoy hunting as much as I did playing baseball, but neither did it bother me to shoot birds out of the sky with a shotgun. In fact, it was kind of exhilarating because it is hard to hit a moving target at a distance, and it became something of a challenge comparable to trying to hit a baseball. (The fact that we ate our prey helped to justify it.) I also did my fair share of fishing—both lake and deep-sea—but today the catch-and-release method is becoming more popular, giving the angler the thrill of the catch while sparing the victims their lives. In the 1980s the burgeoning business of ecotourism was under way, and I both joined and led many trips into the wild to, as it is said, “take only photographs and leave only footprints.” And today the Skeptics Society, which I direct, routinely takes what we call “Geotours” to places such as the Grand Canyon and Death Valley, and there is no shortage of customers. I cannot today imagine going to such places to do what I did as a young hunter.

How perspectives have changed over the decades. Compare the making of the 1979 film Apocalypse Now, in which a water buffalo is almost decapitated while slashed open to the shoulder blades by a machete, to Steven Spielberg’s 2011 film War Horse, in which great care was taken not to harm the horses who were depicting the more than four million horses who were killed or died during World War I. For example, a horse tangled in barbed wire in no-man’s-land was actually struggling to free herself from Styrofoam rubber that was painted silver.78

HOW FAR WILL THE MORAL ARC BEND FOR ANIMALS?

The trend lines we have been tracking in this chapter are encouraging for the animal rights movement. Although the arguments in favor of expanding the moral sphere to include more and more of our fellow sentient beings are superior to those against, the gains, it must be admitted, are modest at best. I predict that hunting and fishing will continue their downward slide in popularity as people’s biophilic propensities for wildlife viewing, photography, hiking, and ecotourism and geotourism increase, but it will never drop to zero. As for the consumption of animals as food products, at the rate we’re going the percentage of vegetarians will not reach the two-digit mark in the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe until about 2025, and in the United States even later (2030 by my calculations), and veganism will be lucky to hit 10 percent anywhere by 2050 (unless something happens to change the rate of growth). But rather than the black-and-white, meat-or-no-meat dichotomy, a flexitarian lifestyle and the gradual weaning of ourselves off of meat is the likelier path we shall see, which will reduce the carnage in the long run.

In the meantime, a workable moral middle ground may be found in a return to small, environmentally stable, and animal-friendly farms—sometimes called local farms or free-range farms or family farms—such as the one Michael Pollan visited in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia that specializes in raising cattle, pigs, chickens, rabbits, turkeys, and sheep that, in the owner’s words, allow each animal “to fully express its physiological distinctiveness.”79 Instead of being treated like an assembly-line widget in a factory farm, all members of species can live out their lives as they would in nature—to the extent that domesticated animals can be said to be in “nature,” given that their own nature has been modified by humans toward the end of living on local farms—thereby fulfilling the moral imperative for all sentient beings to survive, reproduce, and flourish, even if most of the animals will be eventually killed and consumed.80 As a local farmer named Kim Alexander observed with unintentional humor about his charges in the documentary film Free Range, after describing his chickens who frolic outdoors on grassy fields with the sun and wind at their backs, “They have a very good life. They just have one bad day at the end.” Alexander’s moral middle ground between the horrors of factory farming and the impracticality (and undesirability, for most people) of veganism strikes me as a sound and reasoned position with which most of us could live:

I enjoy eating meat, especially when I know where it comes from [local farms v. factory farms] and how it’s been raised and how it’s been processed. The essence of what farming is—growing clean quality food for your family and, when you get good at it, growing it for other people that appreciate it. Out here we factor in all the costs—the costs of a clean environment, the costs of clean food for customers, the costs of treating animals properly with respect and as close to nature as possible, and the costs of what it takes for a family farm to make a decent living.81

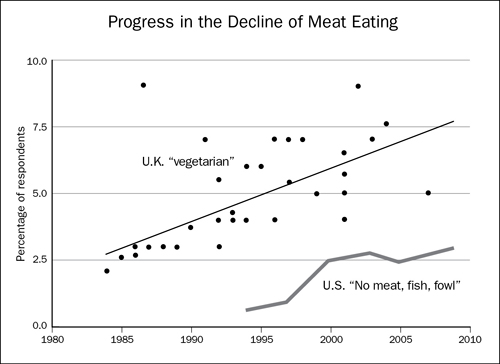

Such farms are starting to catch on as the market demand for food from such sources expands. In the United Kingdom in 2012, for example, free-range eggs outsold those from caged hens for the first time in history (51 percent of the nine billion eggs laid that year). The trend began in 2004, when new rules required farmers to reveal that their eggs were produced by hens stuffed into cages with a floor space the size of an A4 (8x10 inch) piece of paper, leading to a public demand for better treatment of farm animals.82 In the United States, the Whole Foods Market chain is involved in a program called the 5-Step Animal Welfare Rating, and on its web page avows: “All beef, chicken, pork and turkey in our fresh meat cases must come from producers who have achieved certification to Global Animal Partnership’s 5-Step™ Animal Welfare Rating. As their rating program expands to other species, we will require our suppliers for those species to be certified as well.” Figure 8-3, from the Whole Foods Market web page, outlines the steps and encapsulates what is involved in the program.83

Encouragingly, one of the largest of the factory food production corporations, Tyson Foods, Inc., under pressure from animal rights activists and after a graphic hidden-camera investigation by Mercy for Animals at a Tyson pig factory farm in Henryetta, Oklahoma, in late 2013 announced a set of new animal welfare guidelines for its pork suppliers, including a move away from restrictive gestation crates, castration, and tail docking without painkillers, and slamming piglets headfirst into the ground to kill them. As well, gestation crates have now been widely condemned as one of the cruelest factory farming practices in the world, declared to be so inhumane that they are now banned in the entire European Union and in nine US states. Showing the power of the market to make moral changes, some sixty major food providers have demanded their suppliers do away with gestation crates, including Kmart, Costco, Kroger, McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s, Chipotle, and Safeway. That’s real progress.

Figure 8-3. Whole Foods Market 5-Step Animal Welfare Rating Program

This is not some pie-in-the-sky, hippie-dippy, sandal-wearing, tree-hugging, flower child visage of a world filled with Bambi the deer and Babe the pig. It is a practical, economically realistic solution to a moral dilemma. At Whole Foods Market, the driving force behind these initiatives is CEO John Mackey, a pro–free market libertarian who is not only a dietary vegan, but who also practices what he calls “conscious capitalism,” which he defines as “an ethical system based on value creation for all stakeholders,” which include not just owners but also employees, customers, the community, the environment, and even competitors, activists, critics, unions, the media, and, in the case of Whole Foods, the animal stakeholders who are part of the system no less than their human counterparts. Animal welfare is no longer the province of far-left liberals, and John Mackey is a conscious capitalist who is dedicated to improving the food industry in terms of the health and well-being of both consumers and consumed.84

It remains to be seen if family farms could feed a world of seven billion people even with the gradual shift away from meat eating.85 I think not, and so total animal liberation as envisioned by some animal rights activists is likely not even on the horizon. The numbers are staggering. The world population will hit 9.6 billion in about 2050, and then optimistic projections by the United Nations put us back down to about 6 billion by 2100. According to the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), if the entire world stabilized at a European fertility rate of about 1.5 children per woman (2.1 is replacement level), the world population would fall to about 3.5 billion by 2200 and plummet to about 1 billion by 2300,86 which would be sustainable by family farms.