No other body part of the cow is subject to as much deri-

sion and criticism as her eyes. The very sensory organ

that in the Western world is perceived to be the mirror of a living being’s soul or character is the one that most people nowadays view as ugly and dull in cows. You won’t score by complimenting someone on his or her “cow eyes.” But that wasn’t always the case. And the change in perception of the cow’s eye over the past millennia perhaps reflects our changing relationship with the cow.

In contrast to us, the ancient Greeks viewed being cow-eyed as an ideal of beauty. The great Hera, Zeus’s wife and thus the highest goddess, was honored with the flattering nickname Boopis, “the cow-eyed one.” Homer, for instance, repeatedly refers to Hera with that epithet. And that is how we encounter her in most antique sculptures: large and imposing, with wide-open, roundish eyes that overlook more or less graciously her husband’s many sexual escapades. Hera herself was as loyal to her husband as a docile cow. She was considered the patroness of women and monogamous marriage. One of her most famous temples was located on the island of Euboea, where she was said to have married Zeus. The name of this island, too, is a reflection of the beauty of Hera’s eyes: it means “good for cows.”

The shift toward a more negative meaning of the epithet started in Roman times, with the letters of the sharp-tongued orator and politician Marcus Tullius Cicero. To his friend Atticus, Cicero repeatedly called a Roman woman named Clodia, the sister of his archenemy Publius Clodius Pulcher, Boopis, once even Boopis nostra, “our cow-eyed one.” This may at first sound like unfettered praise of Clodia’s beauty—the great Roman poet Catullus had, after all, written some of his most passionate poems for the lady. But maybe Cicero had something completely different in mind. According to Greek mythology, Hera (called Juno by the Romans) was actually not just Zeus’s wife—she was also his sister. By comparing his political enemy’s sister to Hera, Cicero probably meant to imply not only that she had two divinely beautiful cow eyes but also that she, like the cow-eyed goddess, had an incestuous relationship with her brother.

As soon as Early New High German had established itself as the standard language in the German-speaking world, the notion of beautiful cow eyes was a thing of the past. Numerous sayings from the Late Middle Ages proclaim that the eyes of cows and calves express stupidity and wretchedness, most noticeably when the animals face death. “His eyes are crossed like those of a slaughtered calf” was a common expletive in the sixteenth century. The Calvinist writer Johann Baptist Fischart railed against a Catholic priest who had fallen to his knees: “Why does the parson suddenly look as pitiful and compassionate as a slaughtered calf?” The irritated look that cows put on when faced with changes in their familiar surroundings was also seen as the epitome of gawking and ignorant stupidity. “For we have eyes,” the Reformist Martin Luther lectured, “like a cow looking at a new gate.” This was echoed by his contemporary Jakob Böhme, who said that we humans look “at ourselves and at God’s creation like a cow looks at a new barn door.”

With the emergence of modern psychology in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the cow’s facial expression even became pathologized. The 1927 Klinisches Wörterbuch (Clinical dictionary) by Otto Dornblüth, a standard German reference book for medical terminology at the time, lists boopis or “cow eye” as a pathological condition. According to Dornblüth, the term refers to a symptom of hysteria that manifests itself in a “deliberately soulful” facial expression. Hysteria was a condition that was diagnosed almost exclusively in women. The term is derived from the Greek hystera or “womb.” In the Middle Ages, it was assumed that the womb was a kind of animal, an itinerant organ, which in the absence of sexual intercourse went wandering around the woman’s body, thereby triggering the symptoms in question. Although Sigmund Freud didn’t believe in the idea of a wandering womb, he still assumed that hysteria could be cured “by marriage and normal sexual intercourse.” Lack of sexual fulfillment, a problem that probably affected Hera, who was neglected by her husband, was now interpreted as the root cause of a mysterious affliction. A Greek goddess can hardly sink any lower.

Modern conventional medicine eventually degraded the cow eye to a profane object of study. Easy to come by (from slaughterhouses) and structurally more or less identical to the human visual organ, it’s ideally suited for high school biology classes and for medical students who want to investigate the eye’s anatomy up close and personal on the dissecting table. The surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel was one of the people who appreciated this similarity. His first movie, An Andalusian Dog (1929), starts with the vivisection of a wide-open eye that’s being cut in half by the director with a freshly sharpened razor. The scene seems to suggest that it’s the eye of a young woman. In reality it’s the eye of a dead cow, which has been distorted by overexposure.

However, knowing this hardly reduces the almost palpable pain that the image can trigger in the viewer. Buñuel and his coauthor Salvador Dalí chose to attack the key organ of the cinema, the eye, of all things. Like the cow eye, the viewing habits of the movie goers were “dissected.” Dalí later remarked, with a touch of his trademark vanity, that An Andalusian Dog had “ruined ten years of pseudo-intellectual postwar avant-gardism in a single evening.” “That foul thing which is figuratively called abstract art fell at our feet, wounded to the death, never to rise again, after having seen a girl’s eye cut with a razor-blade.” The vivisection scene certainly put an end to an innocent, “cow-eyed” view of film as a medium.

On the whole, the appreciation of the cow eye appears to have been sinking continuously for over two thousand years. The ancient Romans, who started vilifying the cow eye, were also the first ones to engage in systematic cattle breeding. And it seems that the more cows are an integral part of systematic agricultural exploitation, the less inclined we are to consider them as more than hide, flesh, and bones, or, in other words, as beings with a soul—the window to which are, of course, the eyes. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, English essayist William Hazlitt noted that in the case of “animals that are made use of as food” we should “not leave the form standing to reproach us with our gluttony and cruelty.”

When we look a cow in the eye, we take her seriously as a fellow creature, as a being that can reproach us or make us feel guilty. We may even discover the secret that is, according to philosopher Martin Buber, communicated through the eyes of animals alone: “Without needing cooperation of sounds or gestures, most forcibly when they rely wholly on their glance, the eyes express the mystery in its natural prison, the anxiety of becoming.” If, however, we dismiss the look in a cow’s eyes as dull and dumb, if we shrug off the look in the eyes of a slaughtered calf as pathetic, and consider an open, soulful look as pathological and calculating, then it’s undoubtedly easier to look upon the cow as soulless meat stock whose only importance lies in providing us with food.

So once again it’s left to the writers to remind us of the loveliness of cow eyes. After all, beauty is not only found in the eye of the cow but mostly in the eye of the beholder. In his Tierskizzenbüchlein (Little book of animal sketches), Hellmut von Cube, for example, glorifies the cow eye as the seat and epitome of the peaceable serenity that we so admire in cows:

The tranquility of cows, however, . . . is concentrated in the look of their round, dark eyes. The gentleness, patience, and wonder in them are just exterior signs and proclamations. Like the dark, meandering paths leading into a huge, unknown grotto, they reveal the deep, unspeakable peace inside the earth, the way that a few words can often reveal a human being . . . Those to whom these eyes have revealed themselves begin to understand the look of flowers, a look that expresses the same thing, only more subtle and quiet and remote and without the sadness inherent in all conscious creatures.

In his 1983 novel The Cow, Beat Sterchi demonstrates that there are ways of interpreting the look of a slaughtered calf empathically as an expression of great worldly wisdom and resignation. Having been humiliated by the management again and again, the workers of the slaughterhouse where most of the novel is set remember the strengthening and

community-building power of cattle blood. They decide to conduct a libation ritual, a kind of archaic communion. They lead a cow—not a modern meat breed but an Eringer, a traditional Swiss fighting cow—into the slaughterhouse and decorate her with flowers. Then they kill the animal using a technique reminiscent of the Jewish slaughtering method of shechita or its Islamic counterpart dhabiha—by stabbing it in the carotid artery without first stunning it:

The little Eringer . . . mooed feebly, and her eyes lightened as they looked at the men standing in front of her. The cow stood and bled, and it was as though she knew the long history of her kind . . . It was as though this little cow understood the scorn and contempt that had been leveled at her subjugated species since that time, but as though she could still hear, from the back of her skull . . . the echo of her ancestors’ hoofbeats as they thundered over the steppes, like storm clouds, in their great herds, and it was as though this rushing and roaring showed itself unmistakably in the humility in the eyes of the little cow.

Finally, at the center of Martin Mosebach’s 2005 novel Das Beben (The tremor) is a detailed analysis of the holy cows of India. The novel’s protagonist has fled from his unfaithful lover and gone to India. He steps off the plane at Udairpur airport and walks into the terminal building, where he promptly encounters a zebu, the Indian version of the domestic cow. He is immediately taken by the cow but mostly captivated by her look:

There was something childlike in her gentle eyes. They were more closely set together than in European cows. Her head was small and slender and her eyes slightly slanted. The cow didn’t gawk. I do like the protruding European cow eye, too—that meaningful Juno look; but here I saw, possibly heightened by the noble, light-gray color, something of the piety and patience of a donkey.

As if he had read Martin Buber’s analysis of the look of animals that can speak volumes, the narrator soon comes to the conclusion that the pure, disinterested look of the cow is the expression of a secret—that with their eyes, cows can enable humans to share in a transcendent sphere that can’t be articulated. He lets us know that he has “through the figure of the holy cow experienced as much holiness as we can possibly experience on earth. Nothing abstract, but a big, living

animal—larger than humans and impervious to their calculating and analytic way of thinking—that speaks to them through its eyes alone.” The more the narrator thinks about holy cows, the more he understands that all the lyrical things he has said about the cow and her eyes actually also apply to the lover he left behind in Germany. At the same time, he also realizes that the Western world in general and his lover in particular are simply no longer prepared to accept cow-eyed compliments: “No pointer to Homer or Hera the boopis,” he writes, “would be an excuse if she suddenly realized that I had thought of her in connection with a cow.”

So why does the narrator in Mosebach’s novel find it so difficult to communicate the beauty of the cow-eye look to his lover? Or, to put it the other way around, why do so many people so easily dismiss the cow’s eye as ugly?

For one thing, there is the actual eyeball. Cows normally have dark irises (and not, for instance, bright blue or green eyes), and so their pupils are much harder to discern than human pupils. The white sclera surrounding the pupil is often altogether invisible; only occasionally, when cows try to look at something outside their field of vision, when they are frightened or nervous, or when they try to break away, will they roll their eyeballs in their sockets, briefly revealing the whites. With a bit of goodwill and keen poetic perception, such large dark eyes lend themselves to an interpretation as “caves” that lead deep into earth’s interior or to the very bottom of one of the world’s great secrets. And yet, in a society that predominately appreciates a bold, penetrating, analytical look, it can just as easily be interpreted as naive, hopelessly romantic, or simply stupid. Adding to that is the fact that the cow eye protrudes slightly from its socket, giving the cow a googly-eyed look. When seen in humans, the phenomenon is often interpreted as a symptom for an ophthalmic, mental, or thyroid disease.

Apart from that, where the eyes are located on a cow’s head might also contribute to our perception of the cow’s look as inferior. Martin Mosebach has pointed out that the eyes of the Indian zebu are set closer together than those of domestic European cattle. Anyone trying to meet the eyes of our indigenous cow in the same way as we do with other humans—that is, from the front—will almost invariably be disappointed. When looking at cows from the front, the viewer is presented primarily with a wide, horned forehead and a wet nose, with which the cow will probably nuzzle the viewer’s face. Our urge to meet the steady stare of a pair of eyes that are parallel and dominate the front of the face goes unfulfilled.

So when we see the cow’s eye as ugly, we presumably apply inappropriate—that is, human—standards. And yet, there are good, even vital reasons for the design and position of the cow’s eyes. As cows are animals that run and flee, they have to be able to react to the tiniest changes in their environment, even those that take place behind them. The position of their eyes gives them about a 270-degree view; in order to get a 360-degree view of their surroundings and to scan them for suspicious changes, they have to move their head only a

little bit.

However, the fact that the fields of vision of their eyes overlap makes it extremely hard for cows to estimate distances. Their retinas also lack the macula, or “yellow spot” that’s responsible for focusing within a given field of view. Cows see the world relatively blurred. The metal cattle guards often installed on mountain roads seem like insurmountable abysses to them. At times, glaring white lines on the road are enough to give them the illusion of spatial depth. Their color perception is also limited. Cows see mostly colors in the

yellow-green spectrum, which is why they show a great deal of curiosity or aggression when faced with unsuspecting hikers wearing bright yellow raincoats or lime-green T-shirts.

On the other hand, cows have much better night vision than humans and sensory faculties that are superior to ours in some respects. They have excellent hearing, and their sense of smell is approximately fifteen times as acute as ours. Their sense of taste, too, is very pronounced, which is why cows sometimes refuse fodder or water for reasons that we don’t understand. So their sensory perception isn’t more limited or duller than ours. As the environmental philosopher Jakob von Uexküll would put it, cows simply live in a cognitive “bubble” different from ours.

Very few people are privileged to dip into the bubble of cows. Animal psychologist Temple Grandin claims to be one of them. In her book Animals in Translation, she argues that cows perceive the world “like autistic savants.” People with this condition (Grandin is among them) have one or more areas of outstanding expertise, ability, or brilliance but often experience considerable difficulties in mastering everyday situations. They are extremely detail oriented and notice even the smallest changes that would pass most people by. Presumably it’s the inability to prioritize the flood of perceptions and to ignore certain types of information that makes dealing with daily life so difficult for autistic people.

According to Temple Grandin, cows are in a similar situation. They too constantly perceive the world in all its overwhelming richness of detail. If they encounter something they’re unfamiliar with, they’ll consider it, for the time being, a potential danger. That’s why they will be afraid of a raincoat accidentally left on a fence and refuse to walk past it. Or they will, as in Martin Luther’s and Jakob Böhme’s descriptions, stand in front of a new gate with eyes wide with astonishment.

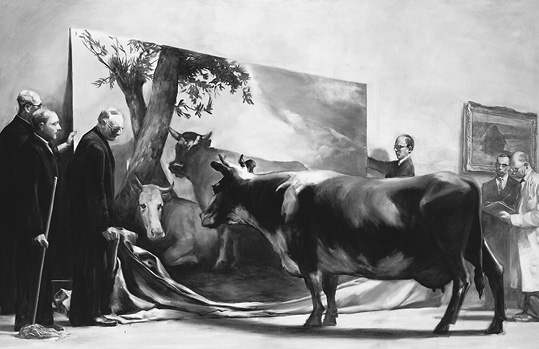

The 1981 oil painting The Innocent Eye Test by American painter Mark Tansey illustrates the great importance we humans attach to the look of the cow’s eye, the differences between human and animal sensory perceptions notwithstanding. As is typical of Tansey’s work, the painting is almost photorealistic. At the same time, the dominance of monochrome gray tones gives the picture the sepia appearance of an old photograph and seems to move the represented scene away from the present. However, the conventional suits that the people in the picture are wearing could well be modern-day ones.

A cow is depicted at the center of the painting. The setting appears to be a museum, where a group of bespectacled researchers are trying to decipher the secret of the cow-eye look, testing its “innocence.” Three of the gentlemen are to the left of the cow, three to the right. One of them is holding a notebook and a pen to document her behavior; another one has a wet mop at the ready to clean away any possible mess the cow might make. The two researchers closest to the cow hold a large cloth to unveil another painting—a picture within the picture. That painting is one of the most famous depictions of cattle in the history of occidental art: The Bull by the Dutch Baroque painter Paulus Potter. In the background is another picture that could be of interest to cows, a haystack by Impressionist Claude Monet. Whoever curated the depicted exhibition certainly had a soft spot for cattle.

However, the scientists are oblivious to the masterpieces around them. They eagerly look at the cow. Her ears are pricked up, and she is attentively looking at the canvas. The young bull in the canvas seems to be looking at the cow in front of him. Tansey obviously captured the moment just after the Paulus Potter painting has been revealed, so we don’t get to know how the cow will react. Will she take an interest in the young bull, because she mistakes his picture for the real thing? Or does she have an innocent eye and, like a young child, can see only two-dimensional colored areas on the canvas but not the three-dimensional world that these areas represent?

Mark Tansey’s The Innocent Eye Test (1981).

The term “innocent eye” in the painting’s title goes back to the English painter and art theorist John Ruskin. In the mid-nineteenth century, he had called on his colleagues to regain “the innocence of the eye; that is to say, a sort of childish perception of these flat stains of color, merely as such, without consciousness of what they signify, as a blind man would see them if suddenly gifted with sight.”

At the same time, the scene is reminiscent of an art story from ancient Greece, of the most famous work of the sculptor Myron. He is said to have created not only a discus thrower, a pentathlete, a dog, an ant, and a cricket, as well as many other works, but also an artificial cow. The cow sculpture was allegedly so realistic that all other beings thought it was alive. A lion allegedly tried to tear the cow to pieces. A bull tried to mount her. A calf came to drink from her udder, while a herd of cows passing by was happy to include her in their midst. A farmer wanted to yoke her to a plow, and a thief tried to steal her. A horsefly sat down on her back and tried to bite the stone, and poor cow-eyed Hera became jealous, because she mistook the cow for one of her husband’s lovers. Even Myron himself is said to have mistaken her for one of his herd. Paulus Potter, the creator of The Bull, was of course at a disadvantage compared with the sculptor, as he was restricted to two dimensions. Nevertheless, Potter’s contemporaries are said to have found the cow paintings so realistic that they felt they could actually smell the cows. If the Dutch master’s work was indeed as mimetic as that of old Myron, the cow in Tansey’s painting should react as enthusiastically to the sight of the young bull as the animals, humans, and ancient gods did to bucula Myronis.

At the end of the day, the cloven-hoofed protagonists in Tansey’s picture are just a piece of art, animals on a canvas. And that’s what makes The Innocent Eye Test so complex. Why would Tansey’s deceptively realistic-looking cow see more than the deceptively realistic-looking bull in Paulus Potter’s painting? And what do we see when we look at the picture? Do we see a cow looking at a bull that’s looking at a cow looking at a bull? Maybe the bull can see us too. Do we even see a bull or a cow or a group of scientists? Or is all we see, after looking at it long enough, just a cluster of flat splashes of color? Are we possibly the actual objects of study in this strange examination of the “innocent eye”? We stand in front of the painting, puzzled, ruminating about these questions with big, round, astonished eyes.