Considering the heavenly happiness that ruminating cows exude, it’s hardly surprising that humans have always sought out the presence of cows or envied those whose livelihood allows them to spend much of their time in the company of cattle. Not unlike stressed city dwellers today, the ancient Greeks projected their ideas about simplicity and carefree living onto the rural population. The verses with which they captured their longing soon grew so much in number that they made up a genre of their own—one that it made sense to name after those who looked after cows. And thus, bucolic poetry—poetry about the lives of cowherds—was born.

As the ancient Greeks knew only too well, people in the country have to deal with the same problems as those in cities—a fact that becomes obvious to city dwellers when they visit the countryside and are confronted with the harsh realities of the herders lives. Theocritus, the most important Greek pastoral poet, summed up this insight as early as the third century BCE in his poem “The Young Cowherd”:

Shepherds, tell me the truth, “am I not beautiful?” Has one of the gods, I wonder, made me on a sudden another mortal? . . . And all the women along the mountain say that I am handsome, and all of them love me; but the city miss has not kissed me, but has run past me, because I am a rustic; and she is not yet aware that beauteous Bacchus used to drive the calf in the valleys. Neither did she know that Venus maddened after a herdsman, and tended flock with him on the Phrygian mountains. And who was Endymion? Was he not a herdsman? Yes, and him Selene kissed as he fed his herds.

In short, bucolic poetry is not so much about the herdsmen’s work but mostly about their leisure. And according to Theocritus or later poets who sang the praise of herdsmen, such as the Roman poet Virgil, the Renaissance poet Petrarch, or the English court poet Sir Philip Sidney, that leisure consists mainly of courtship. The cows (or goats or sheep) that are herded are more like extras in the scene. On the one hand, they are a welcome excuse to retire to the solitude of nature; on the other hand, they make for an idyllic, steadily chewing, and impassive-looking backdrop to the human hustle and bustle. And if the herdsman’s heart is full of sorrow, the cows keep conveniently quiet to let him sing his song—or so English poet Alexander Pope suggests:

In the warm folds the tender flocks remain,

The cattle slumber on the silent plain,

While silent birds neglect their tuneful lays,

Let us, dear Thyrsis, sing of Daphne’s praise.

The idea of country life as communicated in works like Theocritus’s “Cowherd” or this eighteenth-century “Pastoral” is of course mainly a projection of metropolitan desires and longing. In the agricultural sector, keeping cows is considered a labor-intensive livelihood. There’s a good reason for the old German folk saying, “One cow makes moo; many cows make ado” (Eine Kuh macht Muh. Viele Kühe machen Mühe). As Theocritus suggests, those who herd cows, who milk and feed them, hardly have time to canoodle with the womenfolk in the mountains, let alone compose poems in hexameter verse afterwards. This discrepancy might explain why from the seventeenth century onward the term bucolic was replaced by pastoral to refer to the poetry of shepherds rather than that of cowherds.

But even poems about herding cows have taken this contradiction into account. A recurring theme in bucolic poetry is precisely that constant conflict between desire and duty, between leisure and work, between pleasure and reality—in short, between the lover and the cow that must be herded. In his aubade “Das Kchühorn,” the Monk of Salzburg, probably the most important love poet of the late Middle Ages, tells the story of a young couple who treat themselves to an extended nap “in the hay.” Suddenly the sound of the cow horn unceremoniously catapults the maid out of the farmhand’s arms and back into reality; this is a hallmark of the medieval aubade, which always recounts the rude awakening after coitus and the abrupt end of a rendezvous.

Spring’s about

And the herdsmen strum:

Ho! Come out,

the time has come.

She wakes, night’s end

is nigh, she wipes her brow,

goes to attend

the precious cow.

Of course the farmhand doesn’t want to let his lover leave so soon. He’s afraid that the cows might actually be male, human competitors who want the same kind of affection she has just given him. But the maid won’t be sidetracked. The cows haven’t been milked yet, she tells him, and if she were to arrive last, the other maids would tease her.

With udders full there stand the cows,

that’s why I don’t feel great.

Much mockery will I arouse,

if I again am late.

As is usual for bucolic poetry, the two lovers are members of the Third Estate—people of the lowest social stratum. We can assume that the milkmaid and the farmhand acted out the bucolic and erotic fantasies of the members of the Court of Salzburg, which is where the Monk of Salzburg lived and worked. “Das Kchühorn” sings of so-called lower love, which unlike courtly love involves “mere mortals” rather than a knight and a noblewoman. In contrast to courtly love it can also involve sexual fulfillment. Alas, there is not much time for that: the cows are waiting.

The two lovers in the traditional Swiss folk song “Emmenthaler Kühreihen” (Emmenthal cow-calling song) face very similar problems. She spends the whole week with the cows up on the alpine pasture. He doesn’t have time to visit her up there, and if he does get to see his darling once in a while, she has to milk the cows. But the girl knows only too well what to do in such cases:

When I am supposed to be milking

The cow won’t stand still in her place.

So I put my pail just beside me

And entice the young farmhand with grace.

This is obviously no permanent solution. Successful gallivanting, just like profitable milking, needs time. The song ends with the logical conclusion that they should sell the cow and just keep the calf in order to finally have more time for each other:

So we’re selling the cow for a profit,

But the calf we will keep with us here;

Then others can milk every morning,

And we can canoodle, my dear.

Like most antique cowherd poetry, like “Das Kchühorn” of the Monk of Salzburg, this text is written in dialogue form, a light-hearted exchange between a maid and a farmhand. However, as the title implies, this is a specific Swiss form of bucolic poetry, a cow-calling song.

Originally these Kühreihen probably developed from sounds with which the cowherds on the Alpine pastures called their animals to come for milking or to the trough. “When the cows follow the song of the herdsman and come running from all sides,” writes Johann Gottfried Ebel in his Schilderung der Gebirgsvölker der Schweitz (Portrait of the mountain peoples of Switzerland),

All those who have been grazing together or met one another on the way walk one behind the other in a Reihe or line. I suspect that that was the reason cow-calling songs that make them walk in a line were called Kühereihen or Kuhreihen.

The earliest-surviving version of a Kühreihen originates in the Appenzell region and was recorded in the sixteenth century. But a few decades later, cowherd songs had fallen into disrepute. The Basel doctor Theodor Zwinger reported in 1710 that these calls might not just affect cows but also human beings. The Kühreihen supposedly caused the many Swiss mercenary soldiers stationed abroad to suffer from acute homesickness, a phenomenon that was considered typically Swiss and therefore was also referred to as the Swiss disease or mal de Suisse.

“When Kuhreihen were played in Swiss regiments in France,” writes Johann Gottfried Ebel, “the Alpine sons would burst into a flood of tears, and droves of them would be beset by such horrible homesickness, like an epidemic, that they deserted, or died, if they could not return to their fatherland.” The “extraordinary effect of this Alpine music” was supposedly why the whistling or singing of Kühreihen by Swiss mercenary soldiers was forbidden “under pain of death.” And that was not all—Ebel also reported that even Swiss cows got sick with mal de Suisse when someone sang a Kühreihen to them:

When cows of Alpine breeding that have been removed from their country of birth hear this kind of song, images of their former state seem to suddenly take shape in their brains too, triggering a kind of homesickness; they immediately throw their bent tail up in the air, start running, break down all fences and gates and are wild and frantic. This is why in the “St. Gallen” area, where cows bought in the “Appenzell” region often graze, it is forbidden to sing Kuhreihen.

No wonder Romantic artists, who had a weakness for the irrational, for all things magical and mysterious, were fascinated by the natural, almost bestial longing that the Kühreihen could supposedly trigger in humans and animals. What they saw here were works of art that had an inexplicable and irresistible effect on the soul and made soldiers and cows throw off the shackles of civilization and breeding.

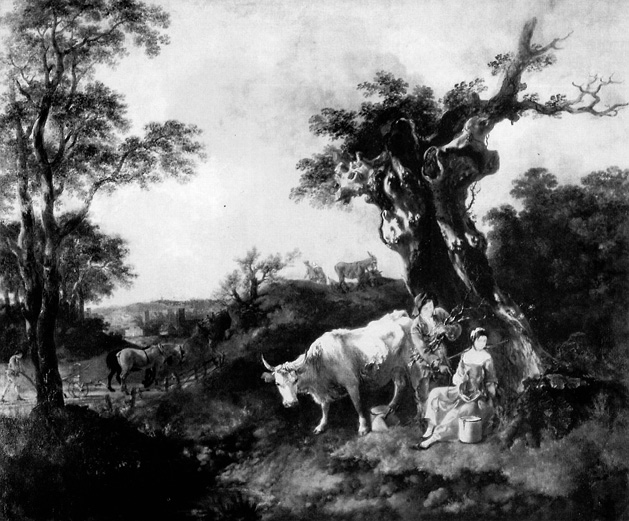

Thomas Gainsborough’s Landscape with a Woodcutter and Milkmaid (1755, oil on canvas, private collection) shows how the bucolic ideal permeated visual art.

Like the legendary song of the Sirens, Kühreihen brought death to those who heard them. Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau commented on the magic powers of these folk songs in his Dictionary of Music. Romantic composers like Robert Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn, and Richard Wagner paid homage to them in their musical works. And the poets Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano included a song about a soldier who follows the lure of the alpenhorn but is then court-martialed and shot, in their collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The youth’s magical horn). It spread the myth of the fatal powers of Kühreihen and made them popular beyond Swiss borders: “Do not spare my young life / Shoot me so the blood splashes out / This I beg of you.”

Such pathos was probably a rather alien concept for writer Heinrich Heine, who referred to himself as the last Romantic poet and had, as he saw it, “dealt the heaviest blows to the meaning of Romantic poetry in Germany.” His poem “Epilogue” is also about last things, and cow herding plays a role in it as well. However, things here are decidedly this-worldly and robust in the best sense of the word:

Graves they say are warm’d by glory

Foolish words and empty story!

Better far the warmth we prove

From a cowgirl deep in love

With her arms around us flung

Reeking with the smell of dung.

In contrast to “Das Kchühorn” and the “Emmenthaler Kühreihen,” the cow here doesn’t keep the lovers apart but is the link between them. She is only indirectly present through the fragrance of her excretions. But it’s just that aroma that gives the imagined rendezvous with the milkmaid its special spice. For one thing, it makes the “foolish words” of the first line of the poem—the pathetic cliché that glory will outlive us and make even death more bearable—look particularly cold and stale.

The smell of cow dung might not seem particularly pleasant, let alone exciting. We have to remember, though, that that fragrance was a lot more popular in the nineteenth century than it is now. With hygiene in the cowsheds not being up to today’s standards, the nourishing and sought-after cow products had an aroma that we would find rather strange. Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, dairy specialist trainees who took part in a blind taste test of milk deemed it tasty only when a pinch of cow dung had been mixed in. In the old days, the smell of bestial excrement was considered so beneficial that some sanatoriums had their own cowsheds in which ailing city dwellers could expose themselves to the healthy fragrances of country life in order to speed up recovery.

In fact, the fragrance may well have had a strong sexual appeal back then. During the winter people often slept with the animals to keep warm. They bedded themselves down next to the cows’ plump and hefty bodies; children were fathered and born in their presence. Consciously or unconsciously the aroma of cow pies may have been linked to memories of the odd lovers’ tryst next to warm, fragrant cow bodies.

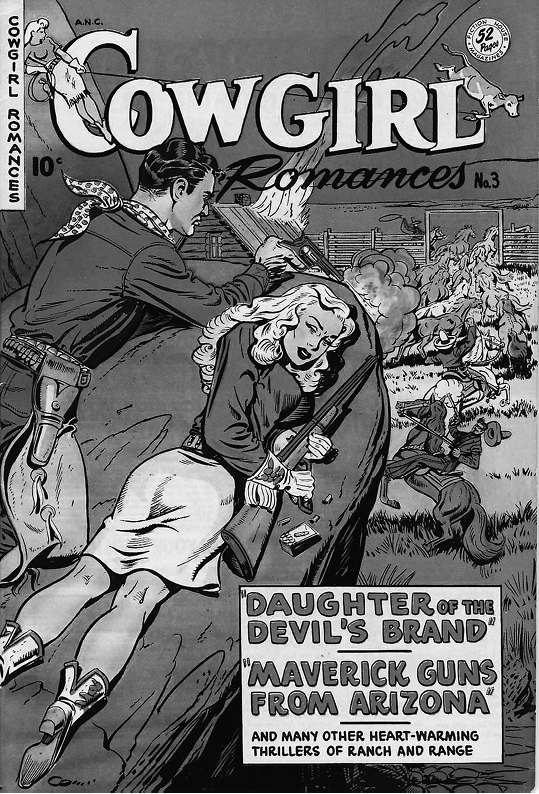

Apart from the aphrodisiac smell of cow pies, the milkmaid also plays a considerable role in instigating intimacy: she is the one who takes the initiative “with her arms around us flung.” So even Heinrich Heine was still caught up in the bucolic cliché of “simple” maids from the countryside who have qualities that the ladies from the cities lack: robust health and a refreshingly daring approach to matters of love. This concept is surprisingly consistent: Theocritus’s young cowherd had already complained about the arrogant and cold-shouldered “city miss” who made a fuss about kissing and praised the comparative straightforwardness of women from the mountains. Some two millennia later, comic book series such as Cowgirl Romances propagated the sexual allure of the women by whom the West was won. And the sexual position in which the woman sits, as it were, “in the saddle,” thus exercising greater control over her partner, is to this day referred to as “the cowgirl.”

Sultry cowgirls were the heroines of this comic book series from the 1950s.

However, although the idea of the sexual recklessness of cowgirls prevailed into the twenty-first century, it had already been the subject of mockery for several hundred years. As early as 1714, the English satirical poet John Gay wrote a travesty of the bucolic genre entitled The Shepherd’s Week, wherein he describes the hapless love of a milkmaid named Marian for a “swain” named Colin Clout. Although Marian’s gentle hands “soft could stroke the udder’d cow,” they could not stroke the skin of arrogant Colin. Depressed, she forgets about the dairy duties at which she used to excel: “But Marian now, devoid of country cares, / Nor yellow butter, nor sage-cheese prepares.” Only at the very end of the poem, when Marian is comforted by the sight of a bull covering a cow, does she regain her appetite:

Thus Marian wail’d, her eyes with tears brimful,

When goody Dobbins brought her cow to bull:

With apron blue to dry her tears she sought,

Then saw the cow well serv’d, and took a groat.

Indeed, according to the great German humorist Wilhelm Busch, cows and poetry, be they bucolic or not, don’t go together at all. In his story Balduin Bählamm, der verhinderte Dichter (Balduin Bählamm, the thwarted poet), Busch describes and illustrates the protagonist’s increasingly desperate attempts to overcome his writer’s block and finally fulfill his destiny by penning a poem. After three failed attempts, Bählamm believes he’s found a solution: he has to leave the confines of his bourgeois urban environment; he must go to where the cows live—into nature.

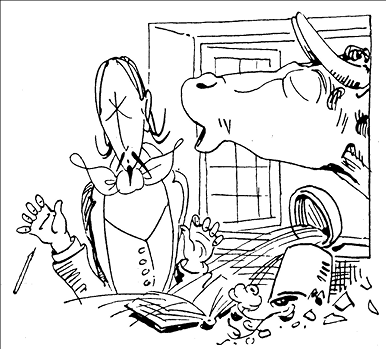

A cow thwarts the poet Bählamm’s work in Wilhelm Busch’s 1883 illustrated book.

So Bählamm leaves his wife and children and goes to the country, where he promptly finds the bucolic idyll he had in mind. A little boy is riding his hobbyhorse, “childlike and naively through a puddle.” An older boy is standing next to his “cozy little dung heap.” His eyes follow a girl who is busy cleaning the cowsheds and in the process, if we are to believe Heinrich Heine, acquiring a very special perfume. The circumstances for writing a poem seem ideal:

As soon as Bählamm there arrives,

Poetic genius revives.

The sun goes down, cowbells are ringing,

And set the poet’s soul a-singing.

Thrilled by the natural extravaganza,

He has high hopes for his first stanza.

Unfortunately Bählamm has not figured in the cows. As long as they keep their distance and are only noticeable from afar as the sound of “cowbells ringing,” they may well inspire the poet. But when they suddenly become tangible and break into the “reality” of the poet’s chamber, the rural idyll comes to a sudden end:

Pots crash, he hears a heavy tread,

Then there appears a horned head.

Eyes closed, mouth wide. What does ensue?

Crude country sounds, a loud ra-moo!

Crushed by the noise are verse and rhyme,

So is the poet’s fine first line.

Harsh sound will undo saint and sage.

The bovine singer leaves the stage.

Cows seem to get in the way of the cowherd’s leisure and the bucolic poet’s work. The very animal that enables bucolic poetry in the first place puts its head through the window. With a great roar it destroys all lyric composure and the metropolitan phantasm that the countryside is a particularly peaceful place conducive to poetic development.

Busch’s story is in a way a “meta-bucolic” poem. It shows that it’s difficult, maybe even impossible, to be among cows and to produce contemplative writings about them at the same time. However peaceful cows may seem, however much they epitomize calm and contentment, they are highly complex beings that can’t easily be squeezed into poems, let alone a genre; and they are completely unsuited as mere extras for the lyric outpourings of out-of-touch city dwellers. As soon as we believe we are part of the happy country life, they break out of the role we have assigned to them and interrupt our dreams abruptly with a resounding and incomprehensible “Ra-moo!” Despite their eminent role in human culture, when it comes to such lofty matters as lovemaking or literature, cows are sometimes simply in the way.