A herd of black-and-white cows, crowded together in the cowshed as dusk falls; the milky light of spring filtering through the window. The cows are snorting, flapping their ears: there’s an air of unrest in the shed. Suddenly the door opens as if by magic. The cows step out, at first still hesitatingly, dodging their heads like the blinded pilgrims in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” But then they become more impetuous. They, in the words of Beat Sterchi, quickly get “over the stupor of being kept shut in all winter” and frolic on the pasture. They romp across the fresh grass, virtually hop, skip, and jump, and quite obviously enjoy their newly gained freedom to the fullest—until they come to a sudden stop in front of an electric fence. The distinctive, regular clicking of the electric fence controller is audible. One of the cows inspects the square box with her mouth and then moos reproachfully. Cut—we see her from behind. The cow is standing on the coast and seems to be staring longingly out to sea.

In the short film Schwarzbunt Märchen (Black-pied fairy-tale), one of the first works of German filmmaker Detlev Buck, there are no human actors at all; according to the credits, it was made with hardly any human cooperation. In Detlev Buck’s typically dry manner, the credits read: “Director: probably Distel oder Imke”—German names for cows. However, the film addresses one of the essential aspects of the human-cow relationship: cows are our prisoners. Even if they are among the happy cows that don’t have to spend their whole lives in the cowshed but are allowed out into the pasture in the summer, their freedom is clearly limited—for example, by electric fences. And even if they are able to overcome the limits that humans impose, there are always other obstacles ahead. In this case it’s the sea, which can be interpreted as a symbol for the endpoint of accessible space or—as infinite and unfathomable as it seems to the cow’s eye—for the end of a lifespan. And that limit is usually also imposed by humans.

One of the most bewildering characteristics of cows is that, despite their size and strength, and although they’re equipped with a quite substantial weapon in the form of horns, they endure their bondage mostly without complaint or resistance. In 1925, poet Bertolt Brecht, ever a stalwart ally of the damned of this earth, wrote the poem “Cow at Cud.” It exemplifies empathetically the contentment and forbearance with which domestic cattle accept their life in the service of humans:

Against the brye rail her dewlap strains.

She feeds on bales of hay, but is polite:

chews thirty times at least every bite,

extracts each drop from straw that splits the veins.

Her hardened haunch and rheumy eyes are old:

so much behind her, nothing to but cud:

the years have cooled the ardour of her blood.

She’s not surprised by anything, I’m told.

And when she works her chops somebody draws

with sweaty hands thick, flyblown milk from her;

it could be clothes-pegs pinching on her udder,

she isn’t bothered by the farmyard raws.

What’s going on is neither here nor there.

So, dropping dung, she takes the evening air.

The fact that the poem is written as a sonnet, the preferred form for wistful love poetry since the Renaissance, points to the narrator’s affection for the oppressed creature. In Petrarch or Shakespeare an unattainable lover usually takes the place of the cow. There is, however, a note of resignation in Brecht’s description of the beloved cow. Her aversion against “evil” and her exploitation by humans are reflected only in the animal’s body language and facial expression (the sadness in her eyes and the disdainful raising of her weary brow) but not in her deeds. And the only action that could be interpreted as a sign of passive resistance—that is, the dropping of a cow pie during milking, is attributed to the auspicious “evening air.” Such devoted animals are unlikely to bring about a revolution. Even on their way to the slaughterhouse cows tend to keep their countenance and resign themselves to their fate, as Beat Sterchi describes in his novel The Cow:

Immune to scorn, Blösch declined to lower her head and butt, made no use of the strength that still dwelt in her great body. Even given the justification of self-defense, she still declined to use any kind of force. She was civilized inside and out, horn to udder, and even on the abattoir platform she remained submissive and meek. These principles had worldwide currency, and Blösch stayed true to them to the last.

With this, Sterchi gives an important hint as to why cows don’t rebel against their fate even when faced with impending death. In animals as big and strong as cows, submissiveness and meekness are understandably desirable selection criteria. Fierceness and the will to resist have been bred out of them as far as possible during thousands of years of captivity.

At the same time, and this may sound paradoxical, cows also benefit from their enslavement by humans. It was only by letting themselves be domesticated by humans that they could rise to be the most widespread and numerous large mammal on earth. They paid the price of freedom for a symbiotic relationship with humans and were thus protected from the dangers and burdens of life in the wild.

Veterinarian and cow specialist Michael Brackmann views it as an “ingenious gambit” from the point of view of biological selection that the Eurasian urus, the aurochs, adapted to humans. By leaving it to humans to provide food and shelter, it could concentrate exclusively on the essentials of the species’s survival: “the passing on and propagation of genes; reproduction.” With this, Brackmann contradicts the popular notion that romanticizes nature and that labels our domestic cattle as particularly stupid and wild animals as especially smart. On the contrary, he reckons, the latter were just not clever enough to get themselves domesticated—“of course only from a socio-biological point of view.”

This, of course, doesn’t mean that domesticated cattle will always behave particularly smart in the short or medium run. There’s an ultimate and very mundane reason why cows dutifully endure their imprisonment, why they usually spare humans who cross their pasture, and why a ramshackle barbed-wire fence or a few milliseconds of electric shock from an electric fence keep them from trying to escape: they’re just not aware of their truly superhuman strength.

Animal psychologist Temple Grandin confirms this opinion. She writes: “The fences farmers use only work to keep cattle in because the cattle don’t realize that they have the power to break through them.” If they occasionally manage to open the latch of a fence, it’s more likely due to chance and their proclivity to repeatedly lick objects. Collective breakaways of cows probably manifest themselves most dramatically in so-called stampedes, which in the case of huge Wild West herds could sometimes cost casual bystanders and cowboys their lives. However, such breakaways are not deliberate acts of resistance but panic reactions. In Elias Canetti’s words, the cows form a “flight crowd,” which is “created by a threat . . . [They] flee together because it is best to flee that way . . . The crowd has, as it were, become all direction, away from danger.”

This is one of the fundamental differences between humans (on whom Canetti’s writing really focuses) and cattle: with the exception of seeing a few especially juicy blades of grass on the other side of the fence, the cow can’t visualize what lies beyond the restricted living space allotted to her and so can’t imagine a utopia that could induce her to break free from her imprisonment. Sociologically speaking, she reacts to push rather than pull factors. As part of the fleeing crowd, she strains to get away from a perceived immediate danger—but she never moves toward a future that she imagines to be better.

And yet, cows have always been used as a benchmark for repressive interpersonal relationships, for forms of slavery, serfdom, or wage-dependent relations. It’s no coincidence that we talk about “a yoke around the neck” in connection with cattle as well as with humans when their bodies and strength are usurped. As early as the seventeenth century, the English political theorist James Harrington commented that Scottish people were “little better than the cattle of the nobility.” And in the nineteenth century, one observer complained that at hiring-fairs, men and women stood “in droves, like cattle, for inspection.” Bertolt Brecht also highlights the human-cattle parallel very explicitly in his teaching play Saint Joan of the Stockyards. The play shows how the employees of Chicago’s slaughterhouses and meat factories are plunged into poverty by their employers’ gambling on the stock market. Although the workers aren’t slaughtered in the actual sense of the word, they are, in every other respect, treated as arbitrarily as those animals that they process to produce canned meat. While waiting in vain for the start of their shift in front of the meat factory that has been closed owing to speculative trading, they compare themselves to cattle: “What do they take us for? Do they think we’ll stand around like steers, ready for anything?” The factory managers who let the starving proletariat, whom they have forced into unemployment, slowly bleed to death are later reviled as “human butchers” by the workers. “For it happens alike with Man and Beast,” it says in Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz, which was written at the same time and takes place in a similar setting. “As the Beast dies, so Man dies, too.”

Even more serious than the metaphorical equation humans = cattle is the accusation that humans are not just treated “like cattle” but worse. In his 1798 Schilderung der Gebirgsvölker der Schweitz (Portrait of the mountain peoples of Switzerland), travel writer Johann Gottfried Ebel vents his outrage at the fact that the peasantry in large areas of Europe was still subject to bondage or hereditary serfdom:

In the Appenzell region cows are treated with more of the kind of respect that is due every useful natural being and are happier than millions of people in Europe, who curse their lives of suppression and hardship. Is it possible that at the end of the eighteenth, the so-called philosophical century, this parallel is a reality, one of such truly scandalous proportions?—Hideous reality!!

Over the following decades the liberation of the peasantry led to a gradual repeal of the manorial system that Ebel deplores here. But in many cases new dependencies took its place, especially with the advancement of industrialization and the development of a large urban working class; and as the example of Brecht’s Saint Joan of the Stockyards shows, the circumstances of this new wage-dependent class were often either equated with those of cattle or exemplified with cows. In Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, too, the fall of its protagonist is mirrored in the description of a slaughterhouse scene. Like the bull that’s stunned by the butcher’s huge hammer and whose killing is described in detail in book four of the novel, Franz Bieberkopf suffers one blow after the next, until he lands way down, at the very bottom rung of society. Similarly, in Walter Ruttmann’s 1927 documentary Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis, we see a quick sequence of images of workers and cows rushing toward the factory and the slaughterhouse, respectively. It almost seems as if the cows have joined the farmers in the industrial revolution and have come to the city to find a new home, becoming the leading metaphor for the circumstances of the workers there.

This parallel highlights various aspects that are responsible for the spate of cow metaphors in the age of industrialization. For one thing, cows, like factory workers in early capitalism, normally appear in “herds”—that is, their owners or employers see them as a faceless crowd rather than a collection of individuals. Secondly, it’s mostly others who benefit from their labor: what they generate is either literally or virtually “milked.” Furthermore, cows and workers both carry out monotonous physical activities at the behest of others, be it at the feeding trough or on the assembly line. And yet, they are expected to not complain, moo, or protest in any other form.

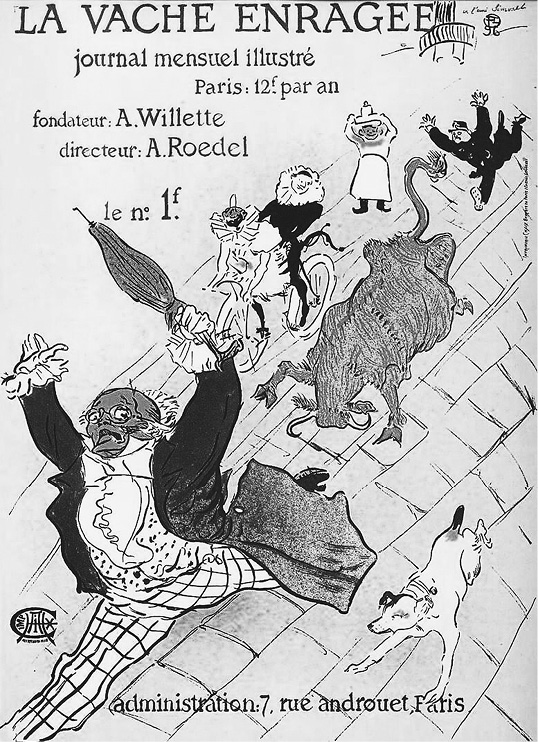

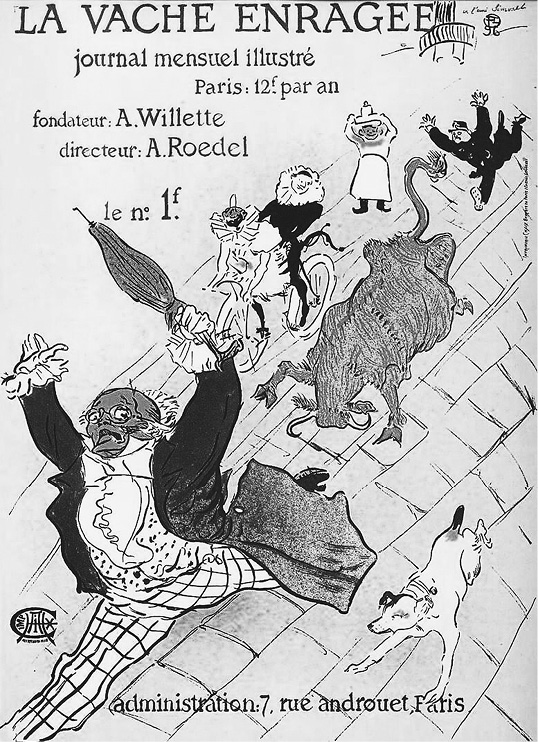

A poster designed by French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec for the magazine La Vache Enragée in 1896 illustrates the political point of view of cows and workers and of the artists who depict them. In it, the “raging cow” who gave the magazine its name chases a desperate older gentleman through the streets of Paris. The policeman in pursuit tries in vain to catch her. Three passers-by observe the whole scene with some amusement. The fleeing gentleman’s portly figure, his frock coat, and fine collarless shirt with its frilly sleeves mark him as a member of the bourgeoisie. The cow’s coat reveals her political colors: red is, after all, not only the color of rage but also that of socialism. The issue of La Vache Enragée was indeed published on the occasion of a carnival-like parade that was organized by Parisian partisan artists as a counter-event to the traditional Fête du Boeuf Gras celebrations and held the day before Ash Wednesday. Instead of honoring “fat beef” as a sign of opulence, the Bohemians celebrated the “enraged cow” as a symbol of the paucity that prevailed among the impoverished inhabitants of Montmartre. At the time, the expression manger la vache enragée, “to eat the enraged cow,” was commonly used in socialist and anarchic circles to paraphrase hunger.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s poster for the magazine La Vache Enragée (1896).

However, it was probably the Russian director Sergei Eisenstein who most impressively equated the destiny of the proletariat with that of cows. He used a cinematic technique of his own invention: the montage. In this technique, independently occurring and causally unrelated dramatic actions are associatively linked to each other by film editing. Eisenstein’s first feature-length film, Strike, was shot in 1925 but is set during the 1917 October Revolution in czarist Russia. Undignified working conditions and the suicide of a colleague have led to an organized walkout in an unidentified factory. (Pre-revolutionary strikes in Yaroslavl, Tsaritsyn, and other cities in Russia’s industrial central region served as historical models for the film.) The factory management first tries to handle the situation by using undercover informants. When that fails and the workers’ demands become more and more exigent, the management has the strikers massacred. The displayed intertitle succinctly reads “Slaughter.” And that’s exactly what the audience gets to see next: images of workers who are brutally murdered by soldiers on horseback in an open field. Then, inserted by abrupt cuts, follow camera shots from a slaughterhouse, the archetypal location of indifferent serial killings. A cow is stunned with a bolt between her eyes. She collapses, her legs still flailing as she lies there, as if she is trying to escape her destiny, but it’s all in vain: the butcher holds her firmly and cuts her main artery with a knife. Black blood gushes from her throat, she rolls her eyes as if looking for its source—then a last (cinematic) cut and we see a battlefield of murdered female and male workers.

In the course of the twentieth century, people were indeed treated like animals, and not just in the metaphorical sense. In some cases animal husbandry practices were directly applied to humans. This started with the Russo-Japanese war but became prevalent during the trench warfare of World War I. It was during that period that barbed wire, invented by American farmer Joseph F. Glidden in 1870, was used for warfare on a large scale. It served to mount lines of defense. The first electric fences were also erected during that time. Charged with a deadly high voltage, they separated German-occupied Belgium from the Netherlands. It was, however, the Nazis who applied animal husbandry practices most relentlessly to humans. Not only were the concentration camps of the Third Reich surrounded by barbed wire and electric fences; according to author Thomas Kapielski, their entire conception was modeled on the cowshed. “As far as the management style, topology, architecture, structures, etc., of these giant cowsheds are concerned,” he writes, “they are—whether consciously or unconsciously—a structural and genealogical matrix for a concentration camp.”

But the inhuman treatment of those who were locked up and murdered in the death camps began much earlier. “The dehumanizing began the moment we climbed into those cattle cars,” is how Holocaust survivor Zwi Bacharach remembers the transport to Auschwitz-Birkenau. “We were treated like cattle.” Accordingly, the metaphor of animal husbandry and killing was applied to the Nazi murderers. Camp physician Aribert Heim, who conducted cruel and often deadly experiments on prisoners, is often called “the butcher of Mauthausen.” Gestapo chief Klaus Barbie, responsible for torturing and murdering Jews and resistance members in occupied France, is referred to as “the butcher of Lyon”; and Governor General Hans Frank, who ruled in Krakow, is called “the butcher of Poland.”

The word “butcher” is meant to emphasize the extraordinary indifference and brutality with which these men killed or tortured their victims. But it doesn’t do justice to the magnitude of the crime. After all, a butcher treats the cows at his mercy more humanely than the Nazi perpetrators treated their victims. And even cows kept in giant cowsheds, no matter how structurally similar these buildings may be to Nazi concentration camps, are still “treated as property, and therefore better”—that is, “like slaves,” in the words of Thomas Kapielski. The latter may be physically unfree, but their owners normally have enough self-interest not to harm them.

Jewish philosopher Vilém Flusser, who in 1940 had to flee his native Prague to escape the Nazis, used the image of cow husbandry to express much more subtle forms of bondage and suppression. Flusser sees cows as “a danger and a threat” mostly because human development might, little by little, follow that of cows, and because humans might themselves, without noticing it, become prisoners—in essence, cows.

To Flusser, the cow is a “machine,” even the very “prototype for the ultimate future machine” that is “designed with ecologically developed technology. We can indeed already claim that the cow is the triumph of a future-oriented technology.” She changes grass into milk. She reproduces automatically. She’s an “authentic open work,” a sort of “open source” document incarnate that’s constantly changed by cross-breeding and can be adjusted to the respective local conditions (mountains, pastures, steppe). And when the cow-machine finally starts showing age-related signs of wear and tear, “its ‘hardware’ can be used in the form of meat, leather, and other consumable products.”

This idea may leave the utilitarian minded largely indifferent. They might even welcome it, were it not, as Flusser notes, for their inclination to imitate machines. From steam engines in the eighteenth century, to the chemical factories of the nineteenth, to the computers and digital networks of the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries, people have always and still do model their thoughts and actions on the latest technical achievements. And according to Flusser, that’s where the danger lies. “The slow substitution of modern machines by machines of the cow kind can lead to an identification of people with cows: human = cow.” As long as humans are surrounded by more than a billion cows, as long as they live in the constant presence of cow products in the form of cheese, milk, leather, and beef and the remains of decommissioned cow-machines, they can’t escape the cows’ influence. “The very presence of the cow has a cow-like influence. Our mind refuses to imagine the consequences.”

Defying all resistance, Flusser subsequently creates a scenario that shows the result of the triumphant cow-machines and could well be part of a dark science-fiction movie like The Matrix or The Island (which didn’t hit screens until years after Flusser’s death). In The Matrix, humankind has been enslaved and is kept as an energy source by an artificial intelligence that maintains world domination. In The Island, a society of clones is led to believe that at the end of their working life they’ll be rewarded with a dream journey to an island paradise. In reality their journey takes them straight to the slaughterhouse as organ donors: they are used as live spare-part depots. In Flusser’s dystopian futuristic vision, humankind has turned into “a herd of cows”:

A grazing and ruminating, content and unselfconscious human race who will consume grass, who will produce milk for an invisible elite of “cowherds” who are interested in it. This kind of human race will be manipulated so gently and cleverly that it will think itself free . . . Life will be restricted to typically bovine functions: birth, consumption, rumination, production, leisure, reproduction, death. A heavenly yet frightening prospect. When we behold the cow, do we not see tomorrow’s humanity?

There are two aspects that turn people into cow-machines in those kinds of films—and if we are to believe Flusser, someday this might happen in the “real world” too. Firstly, people’s intelligence is kept artificially limited so that they can’t revolt against their “owners.” Like cows, they know nothing about the world beyond their cognitive gates. Secondly, this kind of intellectual limitation is primarily designed so that the rulers can use people not in their role as “working animals” but as a tangible resource to be harvested.

In a sense, the parasitic use of human beings, of their bodies and fluids, is already happening. What’s presented as a sci-fi vision is really nothing but a distillation and exaggeration of existing tendencies. Already centuries ago, women, mostly from the lower social classes, made their milk available to a very visible elite of “cowherds.” By working as wet nurses, they relieved the ladies of the nobility and the bourgeoisie from the burdens of nursing. Today, in the twenty-first century, which despite its tender age is already referred to as the “century of the life sciences,” access to the female (and less so the male) body is much more far reaching. The use of the human as resource is focused on Flusser’s themes of “birth,” “production,” and “reproduction.”

As surrogate mothers women carry the children of other parents to full term. Men donate sperm to allow other couples to become pregnant. At the embryonic stage children are selected based on their genetic make-up so that, if necessary, they will later on be able to act as a “savior sibling” for their sick brother or sister by donating bone marrow. All of these procedures reduce the human being, at least temporarily, to his or her function as a harvestable resource. He or she is a milk-producing animal, a uterus, a stock bull, the sum of a set of desirable genetic characteristics. And all of these procedures have been used in a similar way for years in cattle breeding.

Contemporary human beings have an affinity toward Flusser’s other “typical functions of the cow,” a fact that can’t be overlooked. The buzzwords “consumption, rumination, . . . leisure” certainly dominate the modern media and wellness society. There’s a certain appeal in the bovine blueprint for life that revolves around a happily ruminat-

ing existence. Who doesn’t indulge in a simple work-leisure-

consumption routine from time to time, eschewing, as Friedrich Nietzsche writes with respect to cows, “all grave thoughts which bloat the heart”? Who wouldn’t like to believe that we make our decisions independently, free from the manipulations of the media, art, or advertising? Even Flusser has to admit that there’s something desirable about such a dependent but carefree life.

However, he believes that we shouldn’t give in to the gradual “bovinization” of humanity without a fight. “The progress toward the cow can still be stopped.” Not by “denying the obvious advantages of cows and the creative imagination that is revealed through them, but by trying to adapt the cow . . . to true human ideals.” In other words, if for centuries humans have been compared to cows, if at times they treat their fellow humans like cows, if they themselves should one day turn into some type of cow, then it’s high time to treat cows like humans. Or better yet, to treat them the way humans would ideally be treated. And if living in freedom is a human ideal, then humans will have to free the cows who have been their prisoners for thousands of years.