When God made heaven and earth, day and night, and land and water, he created cattle first, and only then, after having prepared the fields and pastures, man and woman. “God blessed them,” the biblical account of creation tells us, “saying, ‘Be fruitful and multiply . . . and let them rule . . . over the cattle and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.’” So when Adam and Eve stepped onto the planet, they were already surrounded by cows. Even the script through which this story is passed down starts, in a way, with the cow: the aleph, א, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, is a stylized version of a horned cow. The Greek alpha, α, which developed into our letter a, is also reminiscent of a frontal view of a cow rotated ninety degrees.

In other mythologies the cow plays an even more prominent and active role in world creation. The ancient Egyptians, for example, believed that the heavens above were really the womb of a gigantic divine cow—one that carried the sun god, Ra, on its back and was the source of the fertile waters of the Nile. According to the pastoral African Fulbe tribe, the earth was created from a drop of milk that came from the udder of the primeval cow Itoori. Germanic mythology tells that the milk and warm tongue of a divine cow called Auðumbla ensured the survival of earth’s first inhabitants.

Cows did indeed play an extraordinary role in the pre- and protohistory of humankind. They supplied milk, and thus the animal protein necessary for our nutrition, and after their death they provided fuel for lamps in the form of tallow. They were able to carry significantly heavier loads than humans and helped to work the farmlands as draft animals. Their hides were used to make waterproof clothing and tent walls, their bones for tool handles and sewing needles. The domestication of cattle almost ten thousand years ago freed us from having to undertake a tiring and dangerous hunt for every meal of fresh meat.

In short, cows played an instrumental part in allowing humankind to settle down and to gradually transition from the nomadic existence of hunters and gatherers to advanced sedentary civilizations. “I am now absolutely convinced,” writes veterinarian and cow expert Michael Brackmann, “that it wasn’t so much the invention of the wheel . . . that enabled Homo sapiens to create advanced civilizations but the domestication of cattle.” American science critic Jeremy Rifkin seconds the idea: “Western civilization has been built, in part, on the back of the bull and the cow.”

The relationship between humans and cattle was (and is) indeed symbiotic. Cattle submitted to us, and in return we took them into our care, helped them find food, cared for them in sickness, and protected them from wild animals. Cattle helped humans develop advanced civilizations, and in turn human support allowed them to populate the whole planet.

Originally endemic to the area that today comprises Iran, Pakistan, and northwestern India, the aurochs, ancestor of our domesticated cattle, had by the end of the last ice age already spread through large parts of Eurasia, eventually arriving in North Africa. It was, however, only with human assistance that its descendants succeeded in reaching other continents. Since the beginning of the modern era, cows have been conquering the entire globe in the wake of European colonizers. On his second journey to America in 1494, Christopher Columbus brought the first cattle to the New World. Following the Spanish conquistadores and missionaries, cattle spread through Central and South America during the sixteenth century. In order to meet the British Empire’s steadily growing appetite for beef, New Zealand and Australia were finally developed as pastureland in the nineteenth century.

Cattle have played a significant part in shaping the face of the earth as we know it. Cattle husbandry gave rise not only to Europe’s cultivated landscape, with its constantly alternating farmlands, pastures, and forests, but also to the endless grasslands of North America and the erosion-threatened clear-cuts of Central and South America, where millions and millions of acres of tropical rain forest had to make way for cattle pastures. Deliberately developed as cattle habitat, these areas were actively shaped by the hooves and mouths of those animals. That’s why Jeremy Rifkin argues that humankind is no longer earth’s subjugator, as the biblical account of creation suggests, but that we are rather up against an “imperium of cattle.” Close to 1.3 billion exemplars of the species graze the earth today. Almost one quarter of the continental mass is used to supply them with grass and feed grain. Cattle are the most abundant group of large mammals in the earth’s entire history. Their total weight amounts to more than double that of the human population.

The reason cattle spread on such a massive scale lies ultimately in their versatility. Cows supply us not only with labor, milk, meat, hide, and bones; the rest of their body parts and secretions are used as well. The German folk song “von Herrn Pasturn sien Kauh” (About the parson’s cow), for example, praises the cow’s universal endowments rather succinctly. Every verse is dedicated to a part of the physical legacy of a recently deceased cow and the respective beneficiaries of the products. The gracious parson gives every member of his congregation a piece of the cow carcass:

And for the olde fire brigade

a pot of axle grease is made

And night watchman Father Thorn

is blowing on his brand-new horn

And the lowly butcher’s boy

all the guts will he employ

Hey, sing, sing along now

about the parson’s cow

The fact that this song survives with hundreds of different verses gives an inkling of just how many things can be made from the remains of a cow. Tallow is an important base for soap, ointment, lipstick, and other cosmetics and in the past was used as wheel and machine grease—and apparently also for fire brigade vehicles. Cow horns are used for combs and piano keys and, although rarely today, for drinking horns and bugles. Guts are made into sausage casings—for example, for the popular Swiss cervelat. Cartilage is used in plastic surgery, whereas eyes end up in the stomachs of gourmets or on biology class dissecting tables. Even the cow’s excrement comes in useful: cow pies are used as fertilizer or dried for fuel, and in the past, nitric acid, an ingredient in the production of gun powder, was extracted from cow urine. The standard corny joke that makes the rounds in the meat industry is that all parts of a cow are processed, except her moo.

The cow has played a special role in humans’ lives for thousands of years, be it as vital livestock or in the form of one of its countless products. So it’s hardly surprising that time and again we have interpreted our existence in relation to cows. The above-mentioned creation stories, as well as countless other myths, fairy tales, novels, poems, plays, films, and paintings are populated with cows and illustrate the dynamic relationship between humans and cattle. Commercials for milk, cheese, or chocolate are inconceivable without cows. Even our everyday language abounds with metaphors, idioms, and sayings that refer to our millennia-long experience with these great creatures. When something or someone fails to materialize for a seemingly endless stretch of time, we feel we are condemned to wait “till the cows come home.” “Don’t have a cow” is the advice given to someone who gets too worked up about something. In German, a man marrying a pregnant woman would in the past have been told disapprovingly that he was “taking the cow with the calf.” When Francophones experience something unexpected, they are likely to react with a surprised “La vache!” while Anglophones prefer the exclamation “Holy cow!”

One way or another, cows have over time come to occupy not only large parts of our globe but also our culture, our language, and our minds. Traditionally symbols of affluence, cows constituted the first natural currency, and we owe the most fundamental principles of capitalism (not to mention the word “capitalism” itself) to cattle husbandry. Believed to have grazed in the Garden of Eden, these quiet, reassuring, and peaceful animals are also a permanent fixture in our utopian imagination. It’s almost impossible to imagine an ideal society or a pastoral idyll without some grazing cows in the background. As livestock that demand a lot of work to rear, they’ve been essential in shaping our relationship with nature—or, rather, with our “second,” culturally modified nature. Author and journalist Eckhard Fuhr argues that values like sustainability, durability, and diligence were only introduced into agriculture when dairy farming was established. That industry imposed the need for careful cattle husbandry and handling of that precious, perishable udder secretion—milk. Cow’s milk has functioned as “a kind of governess . . . It can be conserved only in accordance with, not against, nature.”

Because of this longstanding close relationship between humans and cattle, the cow has virtually become a member of the human family. “The relationship between a mountain dweller and his cows constitutes a genuine mutual exchange of appreciation,” travel writer Johann Gottfried Ebel wrote in 1798 in his Schilderung der Gebirgsvölker der Schweitz (Portrait of the mountain peoples of Switzerland). “The cow gives him everything he requires; in return, the Alpine dairyman cares for and loves it, sometimes more than his children.” According to Ebel, there even was the odd Alpine dairyman who kept his animals “cleaner than himself” and who chose the remedies for his sick cow “more carefully and cautiously than for his sick wife.”

Within the hierarchy of domestic animals the cow has, at least in the Western world, always been somewhat overshadowed by the horse. The latter is a prestigious animal, once used to ride into battle, while the cow just got to pull the camp follower’s cart behind the front lines, if she wasn’t left in the shed altogether. That’s why the cow has a pleasantly unmilitary, even pacifist, image—she is a civilian. She stays at home with the women and children, matching, in a way, the traditional image of women in patriarchal societies. In contrast to the horse, with its bellicose, male connotations, the cow is the preserver. She stands for normality, for everyday life; she generates offspring and food. The Germanic earth-mother goddess Nerthus chose, according to the Roman historian Tacitus, not fiery steeds but cows to draw her wagon across the country, bringing peace to every place she traveled.

And other remarkable parallels exist between women and cows. They are, as Eckhard Fuhr puts it, connected by an “odd biological harmony.” The fertility cycle of cows follows, like that of women, the phases of the moon, and pregnancy in humans and cows lasts almost equally long: both give birth to the fruit of their womb after approximately forty weeks.

Because of these cultural and biological similarities, the cow is sometimes considered almost human, to the point where the boundaries between cattle and humans—and above all, between cows and women—are nearly dissolved. We’ve seen this theme time and again, especially in literature.

Although cows are omnipresent in our lives, thought, and speech, and despite the attempts of more than a few writers to put themselves into their horned heads, cows have continued to puzzle us. Cows are inscrutable and extremely contradictory creatures and as such have challenged us into construing the most conflicting interpretations of their character. There is hardly a domestic animal that has engendered so many and such varied opinions as the cow. Depending on culture, epoch, and personal point of view, she is considered beautiful or ugly, divine or mundane, wise or mad, as a maternal animal or as an object of desire, as a sensitive creature or, in the words of Robert Musil, as “grazing beef.”

In ancient Greece, for example, the expression “cow-eyed” was a flattering epitaph for the gracious goddess Hera; today it would hardly do as a compliment for a woman. Many people think of cows as dumb; expressions such as “stupid cow” or the German “Rindvieh” (cattle) are considered insults. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, however, praised cows as the epitome of perfect worldly happiness. Cartoonists such as Gary Larson prefer to portray cows as figures of fun, while other artists are rather more fascinated by the melancholy cows exude: “Les vaches,” writes the French poet Frédéric Boyer, “sont notre object de mélancolie.” In the end, the individual beholders will decide which ideas, aversions, and desires they want to project onto the cow, what they believe to see in her, and how they portray her. The cow is the sum of all our narratives about her; or, as the philosopher Bruno Latour puts it: “There is no such thing as an objective image of the cow.”

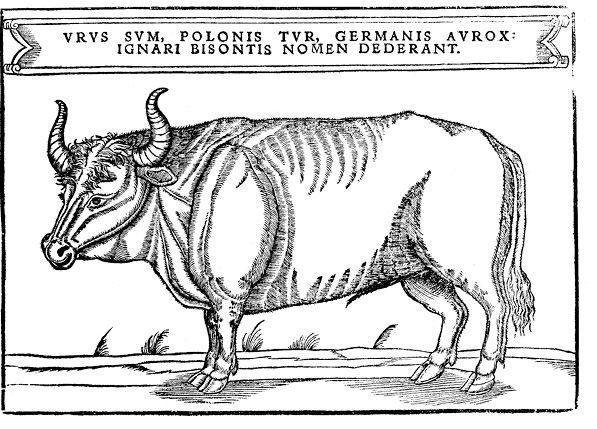

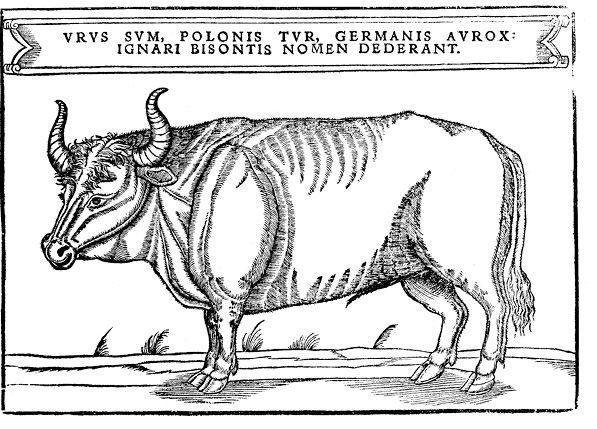

The cow is a human invention in yet another, very different respect. Up to about ten thousand years ago, there were, simply put, only two different kinds of cattle: firstly, Bos primigenius primigenius, commonly known as aurochs or urus, considered to be the ancestor of today’s Western cattle breeds. It was, as Caesar described (with slight exaggeration) in The Gallic Wars, almost as big as an elephant and equipped with mighty “strength and nimbleness,” although that did not prevent it from being driven to extinction by humans. The last specimen died in Poland in 1627. Secondly, there is Bos primigenius namadicus, the so-called Asian aurochs, endemic to the Indian subcontinent and also extinct today. It evolved into the Indian domestic cattle breed zebus.

Sigismund von Herberstein's illustration of an aurochs, ancestor of modern cattle (1556). The caption reads, “I'm ursus, in Polish tur, in German aurox: the unlearned call me bison.”

Among these two breeds of urus, there were presumably already several subgenera that had adapted to their respective ecological, climatological, and geographical circumstances. It was, however, human intervention in breeding that produced the diverse spectrum of cattle breeds we know today. Michael Brackmann postulates that there are around six hundred different cattle breeds in existence. Dutch painter Marleen Felius even records more than a thousand different breeds in her encyclopedia Cattle Breeds.

Many of these breeds are threatened with extinction by the increasing globalization, industrialization, and monopolization of cattle breeding—in Germany, for example, four breeds constitute 97 percent of all cows, although there’s greater diversity in the Alpine states. But it would be overly simplistic, if not presumptuous, to talk about the cow. After all, what do lightweight Dahomey miniature cattle have in common with Angus cows that outweigh them threefold? What connection is there between velvet-skinned, Bardot-eyed Jersey cows and shaggy Scottish Highland cattle? Or between high-volume milk producers like Holsteins and Limousins, which are bred exclusively for their meat; to say nothing of the white cows in England’s Chillingham Park, whose sole raison d’être is to serve as an aesthetic showpiece for humans?

It is, however, pretty safe to say this much: all of these radically different creatures are ruminants of the cattle genus that communicate through sounds we refer to as mooing and that are generally considered good-natured and peaceable. The latter, however, doesn’t apply to steers or bulls, and that point is key: the cow is female. Steers and bulls (that is, sexually mature male cattle) or oxen (castrated male cattle) will make only a cameo appearance in this book. Impressive because of their proverbial virility and indispensable in events like bull fighting or rodeos and for the production of oxtail soup, they play—compared with cows—an inferior role, economically as well as culturally speaking. To us as “herd proprietors,” the bovine is, as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe observed, “significant only in terms of reproduction and nutrition, of milk and calves.” In both instances, the male is only marginally involved.

The focal point of this book is thus the maternal, milk-giving, gentle, approachable, and seemingly familiar cow. The individual chapters are each dedicated to an important aspect of the coexistence of humans and cows. They focus, among other things, on cows as commodities, as suppliers of meat and milk, as sexual objects, as advertising media, as saints and devils, as slaves, as soul comforters, and as a danger to the environment. We’ll ask what cows are trying to tell us when they moo, why milk is proof of the existence of God, and whether good cows go to heaven when they die. What exactly those cows look like—whether they are two-toned like black-and-white Holsteins or rather more monochrome like Swiss brown cows, whether they have humps like Indian zebus or curved horns like Hungarian longhorns—is left to the reader’s taste and imagination.