“Cows,” writes the philosopher Vilém Flusser, “are efficient machines for turning grass into milk.” In 2009 more than 9 million dairy cows grazed in the U.S., altogether yielding more than 21 billion gallons (80 billion liters) of milk. In Canada, during the same period 1.4 million animals produced 2 billion gallons (7.6 billion liters); New Zealand, the world’s biggest exporter of milk, supplied over 4 billion gallons (16 billion liters). The average yield of our “milk machines” is about 1,585 gallons (6,000 liters) per annum, with particularly efficient specimens actually producing up to 5,000 gallons (20,000 liters). Compared with that, the contribution of other mammals to our milk supply is negligible.

So when we use the term “milk,” we normally mean cow’s milk. If we refer to other kinds of milk, we specify their source: mare’s milk, goat’s milk, breast milk. This usage in itself shows what a special role the cow plays in our perception of mammals: it is the quintessential dairy animal. Miraculously, our sense of justice and the legal system seem to be in tune in this case: the usage also correlates with a European Union guideline, according to which non-bovine milk has to be labeled as such with an appropriate addendum. Plant-based products, such as the soy-based drink we casually refer to as “soy milk,” are denied the precious moniker altogether. As the eu labeling protection act for milk and dairy products unambiguously puts it: “The term ‘milk’ shall mean exclusively the normal mammary secretion obtained from one or more milkings without either addition thereto or extraction therefrom.”

The bureaucratic brevity of this regulation may make the process sound rather simple. It is, however, a complex one. In order to be able to produce milk, a cow must first of all have given birth to a calf. And to fulfill its assigned life task as a dairy cow, it should ideally be pregnant once a year. Nowadays, most cows are mated again as early as six to eight weeks after calving. As soon as the milk forms, the first lactation period—that is, the time during which a cow produces milk—begins. It normally lasts 305 days. After this period, the cow is usually “dried off,” meaning that she’s not milked, so that the udder can regenerate before the next little calf is born. Then the whole cycle starts all over again, about seven to ten times in a cow’s life, though a lot less frequently in high-

performance breeds.

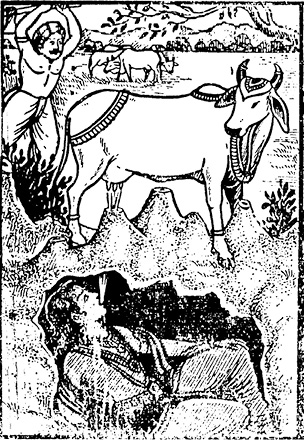

The process of milking is no less complicated. In order for the cow to let anyone besides her calf, for whom it was really intended, have her milk, the cow has to be tricked, in a way. The cow that “milks herself” and voluntarily squirts her milk into a hungry human mouth exists only in Indian mythology. To make the cow believe that her suckling calf is present, milkers first have to massage the cow’s udder. The stimulation causes the cow’s pituitary gland to release oxytocin, which causes the milk to be ejected from the glandular tissue of the udder into what’s called the cistern, above the teats. The milk is then either milked from the teats by hand, a procedure that, according to expert Michael Brackmann, demands nothing less than the “virtuosity of a violinist.” Or the milk is tapped with a milking machine—a lot less virtuosic but gentler on the cow and the milker’s hands—the way it has been done since the end of the nineteenth century and as is customary today.

A cow volunteers her milk to the god Venkatesvara.

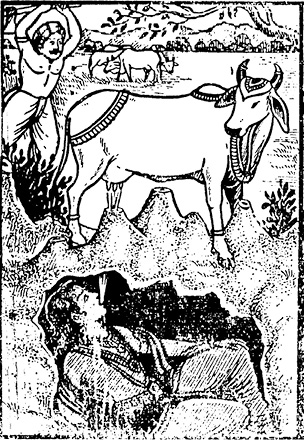

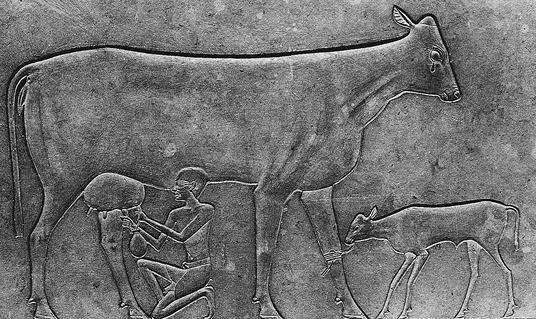

Sometimes, however, these physiological tricks have to be supplemented by psychological manipulation to elicit the much-desired milk from a mother cow. The ancient Egyptians were already familiar with the technique of tying a cow’s calf to the mother’s leg during milking so that the sight and smell of her own offspring would trigger milk ejection. According to the Egyptians, this cunning technique not only makes the milk come down into the udder but also tears come to the cow’s eyes. The mother cow depicted on the sarcophagus of the priestess Kawit weeps bitterly because she has been bereft of her milk. In cattle-herding cultures, like that of the Nuer in East Africa, it’s customary to use calf dolls. When a calf dies in that culture, it’s stuffed and placed in front of the cow to stimulate milk flow.

On the sarcophagus of Queen Kawit, a cow with a calf tied to her leg bemoans the loss of her milk (2000 BCE).

Besides these kinds of olfactory and optical triggers, auditory stimulus is also used to induce cows to give milk. In his novel Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy tells of how the sight of a new milkmaid (Tess, the novel’s eponymous heroine) makes the cows’ milk go “up into their horns.” This metaphor is widely used to describe the fact that cows can hold back their milk; the psychological and physiological reason for this is usually that the stress hormone adrenaline blocks milk flow. Luckily, the head of the dairy knows what to do:

“Folks, we must lift up a stave or two—that’s the only cure for’t.” Songs were often resorted to in dairies hereabout as an enticement to the cows when they showed signs of withholding their usual yield; and the band of milkers at this request burst into melody . . . They had gone through fourteen or fifteen verses of a cheerful ballad about a murderer who was afraid to go to bed in the dark because he saw certain brimstone flames around him.

And indeed, as long as the milkers and milkmaids keep on singing, the milk yield shows a “decided improvement.” Even today some farmers play music in their sheds to increase their cows’ milk production. Unlike the rough Brits of yore, they refrain from using ballads about murderers but usually swear by Mozart, much like parents who believe that the composer’s music promotes their newborns’ development.

It may seem obvious that the smell and sight of a calf stimulates the cow’s pituitary gland or that Eine kleine Nachtmusik has a soothing effect that reduces the release of milk-repressing adrenaline. Much more mysterious and controversial in terms of how it works is what is referred to as “cow blowing.” In this ritual, air is blown into the cow’s vagina or anus—either with a pipe or sometimes directly with the mouth—just prior to milking. The ethnologist Rolf Husmann observed the East African Nuer using this method of cow stimulation and describes

it as follows:

The herdsman wipes the cow’s vagina with the tassel of her tail. He stands either at her side with his head tilted sideways or directly behind the cow, embracing her hind shanks with his hands, and blows air into the cow’s vagina . . . The process is repeated several times. In between, milking movements are performed on the teats and the udder is slightly slapped from between the hind shanks. The Nuer believe that this kind of treatment encourages the cow to give more milk . . . Once the milking is finished, the youngest herdsman squeezes the last drops of milk from the teats and licks if off his fingers, or he may suck it directly from the teats.

The Nuer use this technique mainly for cows that have lost their calves, but the practice is not restricted to East Africa. Mahatma Gandhi, for example, writes in his autobiography that he developed a nauseating aversion to cow’s milk and renounced it when he learned that cows were induced to give milk by this technique, called phooka in India. When he was weakened by dysentery, a doctor tried to talk him into drinking milk, but Gandhi steadfastly refused:

“You can give me the injections,” I replied, “but milk is a different question; I have a vow against it.” “What exactly is the nature of your vow?” the doctor inquired. I told him the whole history and the reasons behind my vow, how, since I had come to know that the cow and buffalo were subjected to the process of phooka, I had conceived a strong disgust for milk.

In his travelogue “Observations in a Voyage through the Kingdom of Ireland,” written in 1680, Englishman Thomas Dineley relates that cow blowing was also very common among Britain’s neighbors to the West: “In Milking the Kine when the milk doth not come down freely, they are observ’d in the North of Ireland & elsewhere, either to thrust in a stiff rope or straw of above a foot and a half into the cow’s bearing place, or else with their mouths to blow in as much wind as they can, with which doing they many times come off with a shitten nose.” Although the actual physiological and psychological benefits of this measure are controversial, its spread across continents and cultures indicates that its benefits outweigh its costs and that it results in a marked increase in milk production—at least according to the herders’ subjective view.

Considering how much effort humans go to in wrangling the udder secretions out of a cow, it’s hardly surprising that milk has always been highly esteemed as a foodstuff. The German Baroque poet Barthold Heinrich Brockes, for example, interpreted the sight of a herd of cows during milking as nothing less than proof of the existence of God. To him, the mysterious transformation—you could even call it transubstantiation—of grass into milk seemed to clearly indicate the rule of a benign creator:

Watching you, my dearest cow

Being milked, I wonder how

It can be that inside you

Grass can turn, if all well chewed,

Into drink as well as food.

It’s a miracle! You do

Distill goodness all for free.

Tell me, human, that indeed

To him who all this has decreed

Now and always glory be!

In vegetarian cultures—in India, for example—where milk is an important source of animal protein, innumerable expressions and metaphors attest to the great value attributed to milk and dairy products. Modern Tamil describes having pleasant thoughts as drinking “the milk of the mind.” Similarly, the feeling of compassion is likened to the sensation of milk collecting in the breast, and the effect that friendly words have on the human soul to milk being poured into the stomach. Among the Indian Coorg, forgoing all pleasure while mourning the dead is seen as an expression of piety—and that means, most of all, not drinking milk during that period. And so one of the worst insults one Coorg can hurl at another Coorg is, “I will drink milk when you die!”

One quality that has been attributed to milk is its ability to imbue those who drink it with a special strength. From a scientific point of view, it’s largely true that milk is healthy. Research shows that drinking milk can prevent medical conditions such as osteoporosis, high blood pressure, and obesity and that the calcium in milk is important for healthy bones. Beyond that, the belief that milk gives you strength is also a kind of symbolic transference. In the same way that ritual cannibalism is about incorporating another human’s strength by eating certain parts of his or her body and in the same way that meat eaters supposedly assimilate the strength of cattle when they eat a bloody steak, we secretly hope that drinking milk will make us as strong as fully grown cows.

This explains why cows, when they make an appearance in milk ads, are often portrayed as especially strong animals (which is quite ironic considering that cows on most commercial farms don’t drink milk but are fed artificial milk formula from an early age). For years now, the commercials and ads of the Swiss Milk Producers’ Association, for example, have featured a cow named Lovely, showing her in always novel and extreme situations of great absurdity. Sometimes she wears a huge bell, its size more appropriate for a belfry, around her strong neck. Sometimes she appears as a karate cow, smashing two stacked-up concrete slabs into bits with her front hooves. At other times, Lovely successfully fights against a sumo wrestler, a boxing kangaroo, and a rhinoceros, whose broken-off horn lies pathetically on the ground after the fight. A commercial for the German company Müller Milk sends a similar message. Here, a cow scores a sporting success in a horse derby. At first it seems as if the usual thoroughbreds with names like Lucky Star and Freedom are going to win the race. But then the commentator’s voice erupts with excitement: “And Elsa comes from behind!” A cow comes galloping past the field, confidently takes the lead, and, cheered on by the spectators, finishes first. A close-up of the cow’s billowing udder leaves no doubt about the secret of Elsa’s strength. At the end of the commercial, during the victory ceremony, an announcement divulges what will happen to the contents of the udder: “Only the milk of the best cows goes into Müller Milk.” Strong cows, the underlying message implies, give strong milk, and those who drink it can partake in this strength. There’s something rather comical about the fact that in the commercial Elsa behaves totally un-cow-like and acts like, of all things, her traditional archenemy, the horse.

In the movie Kung Pow: Enter the Fist, we encounter a similarly tragicomic cow. A karate match between the movie’s hero, the “Chosen One,” and his evil adversary’s martial-arts-trained cow is undisputedly the climax of this martial arts parody. For several minutes, the skills of the two fighters are evenly balanced. But then the Chosen One uses a perfidious trick and manages to turn the tables in his favor: he throws himself under the cow’s belly, grabs her udder with both hands, and simply milks the cow empty. Deprived of her milk and thus her strength, the computer-animated cow collapses. Her opponent leaves the scene victorious. However much the movie scene and the Müller Milk commercial may vary in their style and intended effect, they do have one thing in common: they suggest that those who have milk in their bodies, be it in an udder or in the digestive tract, have superhuman strength.

Likewise, a recent campaign by the California Milk Processor Board (“Got milk?”) suggested, if facetiously, that milk can give humans extraordinary powers. The campaign is centered on a fictitious eccentric glam-rock star named White Gold, whose only form of nourishment is milk. He even plays a transparent guitar filled with the “white gold,” enabling him to improvise and imbibe at the same time. This habit, or so the campaign claims, is what has turned White Gold from a wreck on skid row into a healthy, sexy, muscular rock star. “Before the luscious white mane, the four-hour guitar solos and ripped abdominals, there was White Gold, the man. A mess of frail hair, a dull smile, and a scrawny body . . . Then something changed. White Gold’s voice started sounding like nothing ever heard before . . . His sculpted biceps were shredding his T-shirts. His skin had a sexy, healthy glow. Gossip columns questioned whether White Gold had work done. He strongly denied it, saying, ‘Everyone needs to chill, like my milk does. It’s all good. I’m just a vessel for the white genius to flow.’”

But milk doesn’t just make you strong; it also makes you gentle and peaceful (karate cows are a rare exception to this rule). When Shakespeare’s bloodthirsty Lady Macbeth bemoans her husband’s hesitation to kill the King without further ado, she attributes it to his mind’s being “too full of the milk of human kindness.” In Zimbabwe, when someone is said to be possessed by the devil, a priest will sometimes pour milk over him to purify his soul. The underlying idea is that by drinking milk, we become as calm and relaxed as a ruminating cow. Drinking the traditional glass of milk before going to bed is a symbol of this kind of magical thinking.

The idea is rooted not only in the enviable calm that cows exude but also in our own growth and development. Milk, in the form of breast milk, is usually the first food we ingest, and it’s the only complete, stand-alone form of nourishment. When we are breastfed, we find ourselves in a state of archetypal unity with our mother’s body, a state that the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan termed jouissance. We lack nothing; we desire nothing—apart from more milk, maybe. As soon as the newborn feels its mother’s breast between its lips and the white secretion running down its throat, it is in “heaven.” Even the Promised Land in the Bible is referred to as the “land flowing with milk and honey.”

When the infant is weaned, this heavenly unity is, however, destroyed, and with that the time of innocence ends. As soon as our mother stops breastfeeding us, we are forced to resort to other kinds of food. We wrest the seeds and roots away from plants, we pinch the unborn offspring of chickens the minute they are laid, we take the lives of fish and mammals, and, while the latter are still alive, we take away their milk. Only by drinking it can we fool ourselves into thinking that we can, at least for a moment, return to a state of primordial innocence.

Photographer Annie Leibovitz’s photo of Whoopi Goldberg bathing very vividly illustrates the return to a paradise lost. We see the actress from a bird’s-eye perspective lying in a freestanding enamel bathtub. Her thighs are apart, her bent legs held upwards, her arms stretched out over her head. She lies spread-eagled like a baby whose diapers are being changed; her face is distorted into a rapt grimace. Whoopi Goldberg is lying in a bathtub full of milk. If she were to slide down another inch, the lake of milk would pour into her open mouth; another hand’s breadth and the actress would sink into it completely. If she drowns in it, she will once again be completely at one with herself.

Although childlike and unselfconscious, the photo is also rather erotic—Goldberg’s body posture, her ecstatic facial expression and, most of all, the milk that surrounds her hint that a sexual act has recently taken place. The partner, although invisible or just gone, has left enormous amounts of his semen in the bathtub.

The similarities between milk and semen and, in parallel to that, between a cow’s teats and a man’s penis, can’t be overlooked. It’s quite striking that the act of milking, during which an opaque white viscous jet spurts out of an elongated organ that has been tenderly massaged is reminiscent of male masturbation. “So we see that this . . . fantasy of sucking a penis has the most innocent origin,” writes Sigmund Freud. “It is a recasting of what may be described as a prehistoric impression of sucking at the mother’s or nurse’s breast . . . In most instances, a cow’s udder has aptly played the part of an image intermediate between a nipple and a penis.” The German musician and writer Heinz Strunk therefore always uses the term “milking the lizard” when referring to the act of masturbation in his book Fleisch ist mein Gemüse (Meat is my vegetable). And authors Dieter Schnack and Rainer Neutzling report of a woman who claims to have perceived conception as “being fed,” and her husband’s semen “as breast milk.” Because of that, she allegedly felt “like a well-fed baby” during the first few weeks of her pregnancy. Accordingly, sucking a mother’s breast and, even more so, the (rather less frequently practiced) act of drinking directly from a cow’s udder are reminiscent of the act of fellatio.

So milk is said to have a variety of very special qualities. It allegedly makes us strong and helps improve bone strength. It makes us peaceable and calm and reminds us of the time when we were infants and of a lost paradise. It’s the epitome of all things nutritious and fertile. As such it has female and, to a lesser degree, male connotations. Because of its opaque—well, milky—consistency, it’s also quite mysterious. We can, literally, not see through it. But most of all, it’s white.

Just how important this color is to the way we perceive milk as a healthy and morally and hygienically “pure” substance is easy to appreciate in situations where it’s not white. The most famous example is probably the metaphor with which the poet Paul Celan starts his poem “Death Fugue”: “Black milk of daybreak, we drink it in the evening / we drink it at noon and in the morning / we drink it at night / we drink and we drink.” The historical background to this poem is the Shoah, the systematic mass murder of European Jews during the Third Reich. The crime marked a radical fracture of civilization, a breach that, to this day, calls into question the very foundations of Western morality and culture. In the poem, this complete reversal of all values is succinctly and disquietingly mirrored by the image of black milk.

Whether the milk that Celan describes just looks black in the darkness of the early morning hours or whether it is indeed black is of minor importance. What is crucial is that the contradiction in terms of the phrase and the negative adjective calls into question everything that milk symbolizes—vitality, placidity, motherly care, “human kindness,” and the Promised Land that flows with milk and honey—and turns it into its opposite. If something white suddenly looks black, then there is war instead of peace; motherly and human love turn into hate; and even the most livable country is transformed into a place from which we’d best flee as soon as possible. In view of such a fundamentally corrupted world order, the only hope for improved circumstances exists ex

negativo—that is, in the imagination of all that currently doesn’t exist.

However closely the black milk metaphor is linked with the name Paul Celan in our collective memory, he was not the first one to use it in poetry. In her poem “Into Life,” the poetess Rose Ausländer, who like Celan came from Czernowitz, had already talked about “black milk and heavy absinth” that sprang from the “motherly intimacy” of grief. It seems black milk here has a function similar to black gall, the bodily fluid that, according to ancient humorism, was responsible for melancholy.

Discolored milk is also a source of melancholy in a song by blues singer Robert Johnson (who, in contrast to Paul Celan, certainly was not influenced by Rose Ausländer). In his piece “Milkcow’s Calf Blues,” recorded in 1937, he accuses a cow:

Tell me, milk cow, what on earth is wrong with you?

Ooh, milk cow, what on earth is wrong with you?

Now you have a little new calf, ooh, and your milk is turnin’ blue.

Your calf is hungry, I believe he needs a suck,

Your calf is hungry, ooh, I believe he needs a suck,

But your milk is turnin’ blue, ooh, I believe he’s outta luck.

The blue milk of the mother cow appears to be a metaphor for the singer’s blues. It remains unknown why exactly the milk is discolored, but the reasons for the blues quickly become clear: the cow is behaving like an unreliable lover. The calf, which is hungry and needs feeding urgently, is a symbol for the singer himself. And the blame for the discord between cow and calf lies, as is so often the case, with another man, or, to stick with the metaphor, another bull.

My milk cow’s been ramblin’, ooh, for miles around,

My milk cow’s been ramblin’, ooh, for miles around,

Well, now she been troublin’ some other bull cow, ooh,

Lord, in this man’s town.

So the cow has been unfaithful. She has thrown herself at another fleshy bull and made the cuckold singer “wear horns,” an offense which in the macho blues universe has been known to be punished by instant execution. We can only hope that the “milk cow” fares better than the protagonist of Norbert Kaser’s prose poem “a cow.” Unlike Robert Johnson’s unfaithful animal, Kaser’s cow may not have “brought . . . anyone misfortune,” but she still has to die for the simple reason that her milk has a blue tinge:

she gave ample milk without kicking during milking and without refusing her milk only its milk had a bluish tinge (like in the alpine dairy) . . . but blue isn’t good say the farmers the cow is bewitched. so they decide to slaughter the harbinger of misfortune during the night . . . the corpse was laboriously buried in the dunghill by candlelight lanterns & newfangled batteries. the next day roses flowered on the “grave.”

In fact, in the old days, milk with a blue discoloration, as Johnson and Kaser described, seems to have occurred frequently. It was, however, not due to unfaithful or bewitched dairy cows. According to biologist Herbert Seiler, it’s the result of the milk’s being contaminated with a variant of the bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens—which goes to show that milk shares yet another characteristic with love: it can go sour very quickly.