SUMPTUARY PROHIBITIONS ON FOOD

IN THE REFORMATION

Johanna B. Moyer

Que la Religion est le premier et le principal objet

de la Police …

—Nicolas De La Mare, Traité de la police

In 1577 the French nobleman François de L’Alouette complained that “sumptuary laws, so well received in the past, are now-a-days held in such great contempt. … If these [laws] were well-kept, [the authorities] would not be searching taverns and cabarets for delicious morsels, the people would not ruin themselves on superfluities and great quantities of foods; feasts and banquets would not be so frequent; and the policing of food … would not be so difficult to enforce.”1 While L’Alouette was concerned that the legal codes regulating the quantity and type of food French men and women ate were not being enforced, the reality was that in the sixteenth century these sumptuary laws were increasingly included in a variety of plans to reform early modern society.2

By L’Alouette’s time, the Reformation of Christianity was well underway, and both Catholic and Protestant legislators used sumptuary edicts to interfere in the personal habits of their subjects. Sumptuary statutes restricting the use of luxury clothing, food, banquets, baptisms, weddings, and even funerals were being enacted all over sixteenth-century Europe. The sumptuary laws on food enacted during the Reformation were the ultimate form of the modern twentieth-first-century notion of a “food police.” However, where some modern physicians and legislators argue for legal restrictions on “junk foods” because of concerns with what they see as an increasingly unhealthy public, sixteenth-century legislators were more concerned with what they saw as the spiritual unhealthiness of their subjects. Reformation-era legislators enacted sumptuary legislation to promote religious conformity and affirm the religious practices of their communities. Both Catholics and Protestants enacted sumptuary legislation to ensure that individual members of society did not stray into the religious practices of the rival confession or, even worse, convert to the rival religion.

SUMPTUARY RESTRICTIONS ON FOOD AND BANQUETING

Sumptuary laws had been a regular part of medieval law codes in the centuries before the Reformation. Prior to the sixteenth century, sumptuary edicts had regulated luxuries and conspicuous displays of wealth. Most medieval statutes restricted luxury clothing, such as garments made of silk or luxury furs. In 1294, for example, the French king issued a law which forbade any “bourgeois man or woman” to wear “vair, grey fur, or ermine, … nor are they allowed to wear gold, precious stones, or crowns of gold or silver.” Other parts of the law restricted the number of garments a person could own by social rank.3 Less frequently, these laws restricted foodstuffs or even household items. The same thirteenthcentury law in France also forbade non-nobles from having “any torches of beeswax” and limited the number of dishes that could be served at any one meal.4 Sumptuary laws in the medieval period were often enacted to protect the distinctions between the estates or to preserve the wealth of certain social groups.5 Some medieval laws were tied to Christian notions of morality and were seen as a way to curb the sins of pride, vanity, gluttony, and even lust.

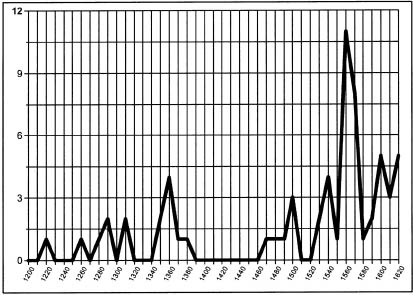

During the Reformation, both Protestant and Catholic areas experienced an upsurge in the enactment of sumptuary laws. This newly enacted body of sumptuary legislation was not only larger than medieval sumptuary law, but some historians argue that it also regulated more items and in more detail.6 Historians of sumptuary legislation attributed this new interest in sumptuary legislation to Protestant governance of morality. These historians also noted a growing number of laws regulating Sabbath observance, gambling, drinking, profanity, and courtship in Protestant countries.7

Figure 3.1 Chart of French Sumptuary Law Frequency

However, more recent studies have disputed this connection. In them historians found little or no change in the content of sumptuary laws. They argue that the frequency of sumptuary law enactment followed the same general pattern in both Catholic and Protestant areas during the Reformation. Still, most agree that there was no change in the content of sumptuary provisions between the Middle Ages and the end of the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, this interpretation does not present a completely accurate picture of sumptuary law in the Reformation as it ignores the fact that there was an increasing concern within the general body of sumptuary law in Europe in the sixteenth century with what people ate. During the Reformation both Protestant and Catholic governments enacted secular regulations on food and banqueting in increasing numbers.

Food regulations had been a regular part of some medieval sumptuary codes. Yet in the sixteenth century food restrictions were enacted in increasing numbers and made up a greater percentage of the total body of sumptuary laws enacted in some countries. In France, for example, only two laws regulating foodstuffs were enacted between 1229 and 1490, or 2.5 percent of total body of medieval sumptuary laws.8 What’s more, in the sixteenth century, six laws were enacted against food items, with the bulk in the 1560s at the start of the religious wars.9 This represented 12.5 percent of the total body of sumptuary law in that century. In Scotland no laws regulating food were enacted before 1551. After that date one-third of all sumptuary regulations enacted by the Scottish Parliament in the sixteenth century targeted the culinary excesses of the Scottish population.10

Both Catholic and Protestant countries saw an increase in the number of sumptuary restrictions on food during the Reformation of Christianity. However, the sumptuary laws that regulated luxury foodstuffs were not identical in Catholic and Protestant areas. Legislators in Catholic areas tended to focus on the type and amount of food eaten. These provisions frequently restricted meats, especially red meats and wild game. A French royal edict of 1533, for example, forbade the eating of lamb and beef,11 and was repeated in a series of laws in the mid sixteenth century against luxury apparel “and the eating of certain meats.”12 Although French law targeted the spending habits of an overweening nobility, Catholic countries like Italy, where the hereditary nobility was less important, also restricted meat and game consumption. A Milanese law of 1565 prohibited peacocks, pheasants, and roe deer,13 while Venetian senators banned similar fowl as early as 1472.14 A later Venetian statute of 1562 added that “wild birds and animals, Indian cocks and hens, and doves shall be strictly forbidden.15

By the mid sixteenth century it was not simply the type of meat eaten that concerned Catholic legislators but also the amount of meat that gluttonous diners consumed. Catholic sumptuary restrictions in this period limited the number of meat dishes that could be legally consumed per meal. The aforementioned Milanese law forbade more than two courses of “flesh/meat” per meal,16 while in Venice the Senate decreed that at “banquets for public and private parties, and indeed at any meal of meat [my emphasis], not more than one course of roast and one of boiled meat may be provided.”17

Both Catholic and Protestant sumptuary laws discouraged general overeating with limits on the number of courses and plates that could be served. Under Louis XIII, French Catholics “of whatsoever quality and condition” were forbidden “more than three services in all and of one simple rank of courses, not stacked on one another: and none can have more than six pieces per course: whether it is porridge or roast” both “in their houses or in public houses and rooms.”18

Protestant legislators created different sorts of sumptuary regulations on foodstuffs. Some Protestant lawmakers avoided sumptuary regulations on food altogether. In England, for example, only one sumptuary law on food was enacted in the early modern era. This law was an early proclamation of Henry VIII; the English Parliament never issued any restrictions on food or banqueting. Moreover, Henry’s proclamation was enacted in 1517, before his quarrel with the pope.19 All the sumptuary statutes and proclamations issued after that date in England dealt with apparel or gilding.20

When Protestant legislators did regulate food and dining, they were less likely to focus on what a person ate and more likely to restrict how much a person ate. Therefore, Henry VIII allowed his subjects all of the varieties of meats and game birds that were forbidden to the French and Italians, including “cranes, swans, bustard, peacock, and all other fowl of like greatness,” however he limited them to “but one dish.”21 Furthermore, each meat had to “stand for one dish.”22 In Calvinist Scotland, consuming meat in general was acceptable in the eyes of the law but was restricted by rank so that “neither an Archbishop, Bishop, nor Earl have at his mess but 8 dishes of meat, nor an Abbot Lord Prior nor Dean have at his meals but 6 dishes of meat, nor a Baron nor Freeholder have but four dishes of meat at his meals, nor a Burgher nor other substantial man spiritual not temporal have at his meals but 3 dishes and but any kind of meat in every dish.”23

Protestant governments employed the particular strategy of limiting the number of dishes or servings per course to control the amount of food that was eaten at a single meal or banquet. Lawmakers in Basel became so desperate to get wedding banquets under control they actually included a suggested menu in a 1629 statute. The menu limited the nuptial feast to three courses, but allowed entrees like “chopped mutton,” “beef, veal, and smoked meat.” However, to curb overeating and cost, the dinner “must begin at 12 o’clock and stop at 4, and everybody must leave by 5 o’clock.”24 Protestant legislators were more concerned with the cost of foodstuffs than with what diners ate. Hence many laws in Protestant areas restricted expensive items like rare meats, wines, and, the more recent addition to European celebrations, sweet deserts and sugary confections. A law from Nuremburg forced revelers to give up expensive fowl like heron and peacock in favor of “roast capon on a side table.”25 German legislators, not trusting the judgment of their citizens, often dictated sensible and less expensive alternatives. Oenophiles were forbidden the pleasures of spiced wine, but could have instead “Franconian or Flemish” or a “similar grade” wines.26 Sumptuary restrictions extended to all sorts of meals and celebrations. A seventeenth-century Swiss law on baptisms and “Christening suppers” forbade any “sweet wine” or confectionary.”27

As the decades passed, legislators increasingly included suggestions for foods that were acceptable in place of the more expensive luxury item. Earlier sumptuary statutes on bridal dinners and other banquets forbade more expensive “imported drugs,28 confectionaries and spices brought from the parts beyond the sea and sold at dear prices to many folk that are very unable to sustain that cost.”29 Four decades later, the Scottish Parliament felt constrained to add that “no person use any manner of dessert of wet and dry confections at banqueting, marriages, baptisms/ feasting or any meals except the fruits growing in Scotland.30 Legislators also worried that the high price and popularity of certain foods led to shortages and increased the price of foodstuffs generally. Others complained that individuals frittered away their fortunes on excessive celebrations.31

The desire to limit expense combined with the Christian belief that overindulgence was a sin. Protestant statutes often limited the cost of banquets and amount of food consumed by limiting the number of guests that could be invited as well as the number of meals that could be given for certain celebrations. The strategy was clearly one of the most popular tools in the antiluxury arsenal of sixteenth-century lawmakers. A late fifteenth-century law in Nuremburg restricted weddings. Guests for the nuptial feast were limited to family and visitors from out of town, although anyone could join the celebration after the banquet ended.32 In 1529, in Zurich, legislators believed that weddings had become “too extravagant” and limited banquet guests to twenty-four, or if you had “a lot” of relations, forty.33 By 1628, in Basel, guests were limited to “four tables of twelve,” and, to ensure compliance, bridal dinners were moved from private homes to “guild houses and public inns.”34 This statute actually limited the cost of the meal per guest.

Wedding customs in Europe were complex in the early modern era. The process of “getting married” included several stages of celebrations, from the betrothal to the removal of the bride to the groom’s home. Where our modern marriage ceremony, whether religious or civil, is believed to constitute the moment in time when the couple are actually “married,” early modern Europeans saw marriage more as the product of a series of events.35 Medieval customs had created dinners and banquets for many of the stages of the marriage celebration, leaving legislators hard-pressed to keep up with the regulation of all meals in the marriage process. By the seventeenth century, Swiss legislators simply dealt with the problem by issuing a blanket prohibition allowing “only one meal … on the wedding day,” fining any additional lunches or dinners on subsequent days.”36 Newlyweds in Protestant Nuremburg were allowed only one “wedding party with seven friends” after they had settled into their new home. 37

Baptisms were also targeted. The municipal government in Basel outlawed “Christening suppers” altogether in 1612 and even included the now standard prohibition on “sweet wine and confectionary.”38 In later centuries Swiss legislators even banned the number of guests allowed at funeral dinners.39

These examples illustrate a larger trend in Protestant sumptuary restrictions on food and banqueting. Virtually all these laws targeted the meal and food served in the context of a celebration or important life event. These meals were public events, important to the life of the Protestant community. Protestant legislators believed that the social function of the meal was as important as the food itself, contending that while excess in eating was bad, public excess was even worse. For the Catholics who enacted sumptuary regulations, however, it was what was eaten and how much was eaten that was important.

THE CASE OF FRANCE

Why was there a difference in the types of sumptuary restrictions enacted against food in Protestant and Catholic areas? The French Wars of Religion (1562–1598) present an excellent opportunity to understand Catholic and Protestant attitudes toward sumptuary regulations. Many partisan treatises on religion, politics, the economy, and the role of the nobility were written during and after the Wars of Religion. Both Catholics and Protestants discuss the ills of France, including overindulgence in luxuries. These texts provide a perfect opportunity to explore opposing ideas about luxury and luxury control.

Catholics

The Catholic side of the debate was presented during the Wars of Religion primarily by members of the Catholic League. The league was founded in 1576 to oppose the ascension of the Protestant Henri de Navarre to the French throne. The Catholic texts diagnosed with the ills of France, speculated on the causes of the Wars of Religion, and of course plied their own candidates for the throne. Many Catholic authors saw the prevalence of luxury, particularly among the French nobility, as one of the chief problems with their kingdom, at once both a cause and effect of the religious troubles in France.

Catholic writers as a group noted the growth in the use of several kinds of luxury before the wars, which they blamed predictably on “heretic and Huguenot rebels.”40 Luxury was rampant in the kingdom, a result of “excess expense on clothing, banquets and superfluity of attendants” as well as large amounts spent on housing and servants.41 Food and banqueting were a constant source of criticism by Catholic authors. One author lamented the current fashion for “sumptuous banquets,”42 while another noted that gourmandizing was rampant among those in government and administration.43 Most authors, however, blamed the upper echelons of French society. The French government and nobility, they complained, spent money and taxes from the French people on luxuries, starving the people and draining money from the poor. Traditionally, excess food and money was supposed to be channeled into charity for the poor. In fact, one of the major reasons for medieval sumptuary laws was to ensure that the wealthy would donate surplus income into charity. Medieval advice manuals for the nobility literally dictated how much income should go for the noble’s own table and how much should be directed to charity.

Catholics often associated luxury, especially the overindulgence of luxury foods, with physical sins. In medieval theology, gluttony had been a “gateway” sin leading to more serious transgressions, particularly lust and fornication. Although some Catholic authors during the French Wars of Religion associated excessive luxury with the sin of idolatry—the “worship of wealth,”44—others associated luxury with the base physical sins of “carnality and purulence.”45 Worse still, they thought that luxury spread from person to person like a disease, spreading the associated sins and ultimately the most dangerous of all sins, the Protestant heresy.

Luxury not only endangered the soul but also damaged an individual’s physical health. Galenism enjoyed a resurgence in popularity in the sixteenth century and was used to justify all sorts of restrictions on food and alcohol.46 Catholics often employed the medical model of Galen’s humors to explain the deleterious effects of overeating and luxury on both the body and the soul. In Galenic humor theory, all food and drink had the potential to cause disease. Sixteenth-century physicians believed that food was incorporated into the body’s structure, a kind of medieval version of “you are what you eat.” Early modern physicians frequently used dietary strictures to manipulate and even change the physical makeup of the body.

Overeating in traditional Galenic medicine was associated with an increase in the moist humors. Food was used by the body to increase blood, which was then turned into other bodily fluids. Excess blood, however, led to disease. Galen noted on several occasions that overeating led to disease, “an excessive consumption of food, however nutritious and excellent is the cause of cold diseases.”47 It is more likely, however, that those who called for sumptuary legislation in Reformation France were influenced by the large quantity of dietary literature that was published during the Reformation. Ken Albala has noted that the dietary advice manuals published during the period from 1530 to 1570 were particularly influenced by the Galenic revival that was such an important part of medicine in this period. Galen pushed out competing medieval and ancient medical authorities to produce a more detailed and precise body of dietary advice.48

Galen’s admonition against an excessive and luxurious lifestyle was seconded by a chorus of condemnations of gluttony from the authors of these Reniassance dietaries.49 Such criticism struck a chord with Catholic authors worried about the transformative powers of food and the role food played as a portal to sin. Moist diseases were caused by excessive lifestyles, Galen argued, including “a surfeit of foods that are moist in power, too many drinks, an excessively luxurious mode of life, sex and frequent baths.”50 Catholic authors saw a direct connection between the “superfluity” of luxury and the “superfluity” of humors in the body that they believed luxury engendered.

Overeating caused illness, but some believed that eating meat, particularly red meat and game in excess, exacerbated the problem. Galen cautioned that meats like beef were not “easily digested” and “generates thicker blood than is suitable.” This led to sanguine illnesses like “cachexy” and “dropsies.”51 Not all early modern authors agreed with Galen, however, on the deleterious effects of meat. Many of the authors of Renaissance dietary guides saw meat as one of the substances most similar to the human body and therefore highly nutritious. Several guidebooks advocated meat, even beef, “contrary to the warnings in Galen, Isaac, and Salerno,”52 Others noted, however, that beef was slow to digest, which could, in fact, destroy some of its nutritive properties.53

Game meats also presented similar problems for strict Galenists. Meats like hare and venison, according to Galen, were difficult to digest and generated “thicker blood.”54 Some early modern dietary advice manuals, however, cited the traditional doctrine of signatures, which held that foods “looked like” their elemental properties. Red foods, therefore, were hot and generated blood.55 The disagreement between the authors of the dietary manuals and the proponents of luxury control was whether or not this blood that was generated posed a health problem for the diner. Many early modern nutritionists argued that darker-fleshed meats were more nutritious, though some thought harder to digest. Nevertheless, the amount of blood that was engendered by meat eating was the amount the body needed to regenerate. Luxury opponents believed that the blood engendered could be excessive and therefore dangerous. The authors of the dietary manuals did note, however, that dark-meated game birds and swans, banned in some sumptuary laws, might generate choler and melancholy in the body of those who consumed them. Lighter-colored chicken, recommended in some laws, was therefore a better choice.56

No matter how early modern nutritionists recast the value of red meat, it could not overcome the long-standing Christian strictures against meat eating. Since the Middle Ages, sumptuary legislation had been motivated by the Christian association of gluttony, meat eating, and illicit sexuality. Some aspects of Renaissance dietary theory reinforced this doctrinal association. Extremely nutritious foods, including meat, often created more blood than the body needed to replenish itself. The surplus was then converted to sperm. The greater the amount of surplus blood, the greater the quantity of sperm, which in turn increased the sex drive.57

Whether early modern diners followed Galen strictly or followed the strictures of a favorite sixteenth-century dietary advice manual, the advice to readers was always to eat a moderate diet.58 For strict Galenists, persistent overindulgence at the table led to illness, which could only be treated by having a physician drain off the excess humor. Joannitius observed that “phlebotomy [bloodletting] is proper in all the cases named above, for if a man eats much meat and drinks much wine … he is not safe: sanguine illness may be generated in him, or perhaps he may drop dead suddenly. But if he is bled, his health can be preserved longer.”59 A patient who persisted untreated, however, ended up obese and diseased, their bodies and souls transformed.

For Catholic League member Nicolas Rolland, the physical dangers of overeating and the luxury of the table could not be separated from the dangers gluttony posed to the soul. The greatest of these dangers was the evils of the Protestant “heresy.” Luxury and Protestantism had taken over foreign governments, Rolland noted, with disastrous consequences. The “poster boy” for these dangers was the English Protestant king, Henry VIII. Rolland described what he believed had happened to the English king after he left the Catholic Church.

He had been at the start of his reign, the most handsome and agreeable Prince who was well regarded, but since he separated from the Church, he became strangely voluptuous; he was so gluttonous and gourmandized beyond measure. This rendered him so large and so fat, that he became in a short period of time completely deformed, he could no longer pass through the small doors of the bedrooms and loos, nor himself climb the height of the stairs to go to the rooms of his palace, which made it necessary to lift him in the air with machines and artifices; they sat him in a chair.60

Overeating had horribly transformed Henry’s physical body, but ultimately it was the sign of a diseased soul. For Rolland and other Catholics, luxury was a physical symptom of heresy; the sinful state of the soul apparent in the diseased state of the physical body.61

The damage caused by luxury and overeating to the bodies of individual sinners mirrored the larger damage done to the greater body politic of France. The metaphor of the body politic became more popular in the sixteenth century, especially with the growth of new theories on rational government and absolutism in France. Each organ or member of the human body had a specific function, and all of the other parts of the body depended upon that function for life. Early modern thought linked the specialized functions of each part of the body to the different but interdependent functions of society. The social classes, economic functions, and even religion needed to be balanced and regulated, just as the members and humors of the body need to be balanced. For the human body, the intellect was the instrument of regulation, while for the body politic of France it was the job of the government and the king. For the opponents of luxury, Catholic and Protestant alike, the damage caused by luxury spread from the individual luxury user to the society at large. One overeater became many overeaters. Entire segments of society became “infected” with luxury, and, as one part slipped out of balance, the entire body politic was endangered. Luxury spread like an infection endangering the health of the nation.62

For Catholic luxury opponents, the flow of wealth in the kingdom mirrored the flow of blood in the human body. During the Wars of Religion, wealth flowed upward to the king and nobility, starving the lesser members of the body politic. The royal court was now “corrupted and infected” with the disease of luxury.63 As the luxury unbalanced the humors of the body of France, it created the disease of heresy. Protestantism now infected a significant portion of the French nobility, and war had resulted. The humors of the body politic were unbalanced, and the king was responsible. He must now act in the role of physician to heal the body politic of luxury and stamp out the disease of heresy. Leaguer Rolland admonished the king “to heal this body [France] so sick, it is necessary as a good and true doctor, that you have the will and desire to bring the healthful medicine.”64 Sumptuary laws were essential to halting this process. They served as preventative phlebotomy did, staving off a much larger bloodletting of civil war that was inevitable with the buildup of sanguineous humors in the body politic.

Protestants

Protestant writers during the French Wars of Religion agreed that luxury was more prevalent than ever and that luxury was both a cause and effect of France’s current religious troubles. They also largely agreed with Catholic authors that the French nobility was the locus of the problem. Some Protestants too criticized excessive consumption of luxury food and banqueting.65 However, Protestants did not rank the evils of excess at the table as highly as other types of overindulgence. Many Protestants argued that overspending on apparel was a much more pressing problem for France, especially vestments made from imported materials or that incorporated gold and silver accessories. The Protestant writer François de La Noue actually ranked several kinds of luxury items their order of damaging effects. “In first place would be superfluity in clothing” (115). He believed that architecture and housing had recently gotten out of hand, so he ranked luxury housing second, followed by furnishings third (195–197). Only fourth on his list were “expenses of the mouth,” but combined with excessive attendants of the nobility. However, he went on to emphasize the number of horses and servants nobles kept rather than what the aristocracy spent on their tables (199.

Indeed, many Protestants argued that luxury meats, wines, and even banqueting were fine as long as done in moderation (see, for example, 587). When they did attack banqueting, they condemned lavish parties, particularly those that were accompanied by “masques, gambling and superfluous attendants” (119). On the other hand, Laffemas scoffed at past sumptuary laws that had been designed to “impede banquets and nocturnal debaucheries.” These had not worked, he argued; instead they “provoke luxury rather than stop it.”66 Some Protestants even argued that the Catholic desire to restrict food, especially meat, is nothing more than a form of idolatry, a kind of “worship” of food.67

Most Protestants writers agreed that the worst form of luxury infecting France was the rage for apparel made from imported silks and velvets and the use of gold and silver to decorate clothing, furnishings, homes, and carriages. The purchase of foreign cloth and apparel decreased employment for the French people, and the use of specie in luxury items immobilized currency. These writers were increasingly influenced as the sixteenth century wore on by the economic “philosophy” of mercantilism. Mercantilists preached the importance of preserving gold and silver within the boundaries of France and advanced the domestic luxury industry to promote employment.68

This rhetoric reached its pinnacle in a series of economic treatises penned by the Protestant Barthelemy de Laffemas. He was arguably the Mercantilists’ greatest opponent of foreign luxury items and items that incorporated gold and silver. He tirelessly campaigned for a governmentsponsored domestic silk industry which he believed would create substantial employment. In a treatise written at the end of the Wars of Religion, Laffemas railed against “the abuse of gold and silver laces, and the evil brings pearls and precious stones …”69 He called for sumptuary laws banning imported silks,70 gold and silver laces, and gilded furniture. However, Laffemas hoped to legalize domestically produced silk for apparel.71

It was not the grotesque figure of a gluttonous Henry VIII that haunted French Protestants like Laffemas and de La Noue but the image of young French nobles elaborately decked out with hats “in the form of a crust of bread” and elaborate apparel bought from Venice. The irony was that while the Venetians and other Italian city-states became rich from these purchases, “the simplicity of their [Venetian] apparel make their coffers teem with riches, and their Senate shines with prudence and wisdom, and their [sumptuary] statutes are inviolably observed and to the contrary that we, with our short shoes and long doublets have thrown our [sumptuary] laws out of the window … and our coffers are almost always drained of gold” (La Noue 194–195). One of the greatest tragedies of the Wars of Religion, in Laffemas’s opinion, was not the loss of life but the loss of French manufactures (5–6).

Protestants too employed a disease model to explain the dangers of luxury consumption. Luxury damaged the body politic leading to “most incurable sickness of the universal body” (33). Protestant authors also employed Galenic humor theory, arguing that “continuous superfluous expense” unbalanced the humors leading to fever and illness (191). However, Protestants used this model less often than Catholic authors who attacked luxury. Moreover, those Protestants who did employ the Galenic model used it in a different manner than their Catholic counterparts.

Protestants also drew parallels between the damage caused by luxury to the human body and the damage excess inflicted on the French nation. Rather than a disease metaphor, however, many Protestant authors saw luxury more as a “wound” to the body politic. For Protestants the danger of luxury was not only the buildup of humors within the body politic of France but the constant “bleeding out” of humor from the body politic in the form of cash to pay for imported luxuries. The flow of cash mimicked the flow of blood from a wound in the body. Most Protestants did not see luxury foodstuffs as the problem, indeed most saw food in moderation as healthy for the body. Even luxury apparel could be healthy for the body politic in moderation, if it was domestically produced and consumed. Such luxuries circulated the “blood” of the body politic creating employment and feeding the lower orders.72 De La Noue made this distinction clear. He dismissed the need to individually discuss the damage done by each kind of luxury that was rampant in France in his time as being as pointless “as those who have invented auricular confession have divided mortal and venal sins into infinity of roots and branches.” Rather, he argued, the damage done by luxury was in its “entire bulk” to the patrimonies of those who purchased luxuries and to the kingdom of France (116). For the Protestants, luxury did not pose an internal threat to the body and salvation of the individual. Rather, the use of luxury posed an external threat to the group, to the body politic of France.

THE REFORMATION AND SUMPTUARY LEGISLATION

Catholics, as we have seen, called for antiluxury regulations on food and banqueting, hoping to curb overeating and the damage done by gluttony to the body politic. Although some Protestants also wanted to restrict food and banqueting, more often French Protestants called for restrictions on clothing and foreign luxuries. These differing views of luxury during and after the French Wars of Religion not only give insight into the theological differences between these two branches of Christianity but also provides insight into the larger pattern of the sumptuary regulation of food in Europe in this period. Sumptuary restrictions were one means by which Catholics and Protestants enforced their theology in the post-Reformation era.

Although Catholicism is often correctly cast as the branch of Reformation Christianity that gave the individual the least control over their salvation, it was also true that the individual Catholic’s path to salvation depended heavily on ascetic practices. The responsibility for following these practices fell on the individual believer. Sumptuary laws on food in Catholic areas reinforced this responsibility by emphasizing what foods should and should not be eaten and mirrored the central theological practice of fasting for the atonement of sin. Perhaps the historiographical cliché that it was only Protestantism which gave the individual believer control of his or her salvation needs to be qualified. The arithmetical piety of Catholicism ultimately placed the onus on the individual to atone for each sin. Moreover, sumptuary legislation tried to steer the Catholic believer away from the more serious sins that were associated with overeating, including gluttony, lust, anger, and pride.

Catholic theology meshed nicely with the revival of Galenism that swept through Europe in this period. Galenists preached that meat eating, overeating, and the imbalance in humors which accompanied these practices, led to behavioral changes, including an increased sex drive and increased aggression. These physical problems mirrored the spiritual problems that luxury caused, including fornication and violence. This is why so many authors blamed the French nobility for the luxury problem in France. Nobles were seen not only as more likely to bear the expense of overeating but also as more prone to violence.73

Galenism also meshed nicely with Catholicism because it was a very physical religion in which the control of the physical body figured prominently in the believer’s path to salvation. Not surprisingly, by the seventeenth century, Protestants gravitated away from Galenism toward the chemical view of the body offered by Paracelsus.74 Catholic sumptuary law embodied a Galenic view of the body where sin and disease were equated and therefore pushed regulations that advocated each person’s control of his or her own body.

Protestant legislators, conversely, were not interested in the individual diner. Sumptuary legislation in Protestant areas ran the gamut from control of communal displays of eating, in places like Switzerland and Germany, to little or no concern with restrictions on luxury foods, as in England. For Protestants, it was the communal role of food and luxury use that was important. Hence the laws in Protestant areas targeted food in the context of weddings, baptisms, and even funerals. The English did not even bother to enact sumptuary restrictions on food after their break with Catholicism. The French Protestants who wrote on luxury glossed over the deleterious effects of meat eating, even proclaiming it to be healthful for the body while producing diatribes against the evils of imported luxury apparel. The use of Galenism in the French Reformed treatises suggests that Protestants too were concerned with a “body,” but it was not the individual body of the believer that worried Protestant legislators. Sumptuary restrictions were designed to safeguard the mystical body of believers, or the “Elect” in the language of Calvinism. French Protestants used the Galenic model of the body to discuss the damage that luxury did to the body of believers in France, but ultimately to safeguard the economic welfare of all French subjects. The Calvinists of Switzerland used sumptuary legislation on food to protect those predestined for salvation from the dangerous eating practices of members of the community whose overeating suggested they might not be saved.

Ultimately, sumptuary regulations in the Reformation spoke to the Christian practice of fasting. Fasting served very different functions in Protestants and Catholic theology. Raymond Mentzer has suggested that Protestants “modified” the Catholic practice of fasting during the Reformation. The major reformers, including Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli, all rejected fasting as a path to salvation.75 For Protestants, fasting was a “liturgical rite,” part of the cycle of worship and a practice that served to “bind the community.” Fasting was often a response to adversity, as during the French Wars of Religion. For Catholics, fasting was an individual act, just as sumptuary legislation in Catholic areas targeted individual diners. However, for Protestants, fasting was a communal act, “calling attention to the body of believers.”76 The symbolic nature of fasting, Mentzer argues, reflected Protestant rejection of transubstantiation. Catholics continued to believe that God was physically present in the host, but Protestants believed His was only a spiritual presence. When Catholics took Communion, they fasted to cleanse their own bodies so as to receive the real, physical body of Christ. Protestants, on the other hand, fasted as spiritual preparation because it was their spirits that connected with the spirit of Christ in the Eucharist.77

The public nature of fasting for Protestants was reinforced by the issuance of Lenten laws. A comparison of France with England and Scotland shows that the British enacted far more laws enforcing abstinence from red meat during Lent in the sixteenth century than Catholic France. The French issued only four royal laws ordering abstinence during Lent, generally prohibiting “the sale … of any type of meat during Lent.”78 By contrast, the English and Scottish enacted dozens of Lenten laws in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.79 The first English law was enacted by the Calvinist-influenced Edward VI.80

This is not to suggest that the traditional interpretations of sumptuary laws as parts of other projects of governance are incorrect. French Protestants were clearly influenced by economic mercantilism, as were Protestants in other countries. Moreover, the authors of both religions who wrote against luxury in France targeted the nobility and wanted to use sumptuary legislation not only to curb aristocratic wealth but also to create a new role for the nobility in French society. This fact suggests that sumptuary legislation in this period was also motivated by a desire to stabilize the social hierarchy. This too can be seen in Italy where the sumptuary regulations on food contained laws that conform to both the “Catholic” pattern and the “Protestant” model. In Italy, however, where religion was debated but never really in doubt, social considerations probably outweighed religious motives.

At the bottom of all sumptuary impulses in the Reformation, however, was the notion of community. Sumptuary legislation was now being used as a form of religious policing, designed to force the members of the religious community to conform to the theological practices of the group. Just as Catholic governments destroyed books banned by the Church in the Index of Prohibited Books and Protestant governments enacted laws compelling Sabbath observance and banning adultery, sumptuary laws were used by both sides to enforce religious dogma. Both Catholics and Protestants in the sixteenth century incorporated into sumptuary legislation notions about the human body reintroduced by the medical humanism of the sixteenth century. These Galenic views of the body were transformed to express theological notions of sin, salvation, and membership in the Christian community.

Did these differing views of “community” impact the content of sumptuary laws during the Reformation? The answer must be both yes and no. There was a change in the content of laws from both Catholic and Protestant areas in the sense that there was an increased emphasis on the regulation of food. It is also clear that the content of Protestant and Catholic food laws was different. In Catholic areas, this meant sumptuary restrictions on food controlled the private acts of culinary excess, but in Protestant areas sumptuary laws controlled the public acts of food and banqueting.

This does not mean, however, that Reformation-era legislators enacted different sorts of regulations than those enacted by their medieval predecessors. It has been noted by several historians that there were food “patterns” associated with each religion. Northern European countries like England and Germany that converted to Protestantism also favored diets centered on beer, butter, and pork. This was true both before and after conversion. Southern European countries like France and Italy, however, favored wine, olive oil, and mutton, before and after the Reformation. They also remained Catholic.81

The content of sumptuary legislation also followed this pattern. Although the types of antiluxury statutes regulating food and banqueting differed by religion, the laws tended to be the same as those enacted in the same area before the Reformation. This begs the question, as Mack Holt has put it, what was the connection between food culture and religion in the Reformation? It seems likely that, as Holt found for drinking patterns, religion simply reinforced differences in eating patterns and the cultural hegemony of certain foods.82 Clearly, food is always a central element in the affirmation of community. During the Reformation, food practices and the culture of food became one of many “tools at hand” that could be redeployed by the Reformation police to enforce new Reformation theologies and new definitions of community.

Notes

1. De L’Alouette, Traité des nobles et des vertus, 65.

2. Sumptuary programs stood at the crossroads of many legislative projects in the sixteenth century. Early modern restrictions on personal consumption regulated the social structure, instituted poor relief, promoted religious conformity, and managed the economy.

3. Isambert, Recueil général des anciennes lois françaises, 1:697–698, arts. 2 and 6.

4. Ibid., arts. 13 and 14.

5. The older historiography of sumptuary laws in France, for example, often presented early modern sumptuary laws as safeguards enacted, in the words of Vertot, to save the “great families from ruin.” Godard de Donville and Freudenberger argued that sumptuary laws were intended to prevent a competition of display between the sword and robe nobilities. Other historians argued that sumptuary laws in this period were enacted to preserve distinctions in ranks after the rise of the robe nobility. Schalk saw sumptuary legislation in this period as an attempt to reinforce the old symbols of nobility, particularly clothing, because they were now available to wealthy non-nobles. See L’abbé de Vertot, “Dissertation sur l’Etablissement Des Lois Somptuaires,” in C. Leber, ed., Collection des Meilleurs Dissertations et Traités Particuliers relatifs à l’histoire de France (G. A. Dentu: Paris, 1838), 10:467; Louise Godard de Donville, Significantion de la mode sous Louis XIII (Edisud: Aix-en-Provence, 1976), 206, 211; Freudenberger, “Fashion, Sumptuary Law, and Business,” 40; H. Baudrillart, Histoire du luxe, privé et public depuis l’antiquité, 4 vols. (Hachette: Paris, 1878), 3:441–442; and Davis Bitton, The French Nobility in Crisis,1560–1640 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1969), 67, 101–107. See Ellery Schalk, From Valor to Pedigree, Ideas of Nobility in France in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 151–152. Legislators at times cited the desire to preserve fortunes as one justification for enactment. See, for example, the royal French edict of July 12, 1559. Isambert, Recueil général des anciennes lois françaises, 13:101.

6. See Greenfield, “Sumptuary Law in Nürnberg,” 86; Frances Baldwin, “Sumptuary Legislation and Personal Regulation in England,” Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science 44 (1926): 270; Harte, “State Control of Dress,” 151; Hooper, “The Tudor Sumptuary Laws,” 96. See also Freudenberger, “Fashion, Sumptuary Law, and Business,” 37; Hunt, Governance of the Consuming Passions, 183–189. Greenfield and Baldwin noted that sumptuary legislation in the Reformation was more “complex” and hierarchical. Greenfield, “Sumptuary Law in Nürnberg,” 6; and Baldwin, “Sumptuary Legislation and Personal Regulation,” 136.

Early modern legislators we also more determined to enforce these new sumptuary restrictions. In the late fifteenth century, for example, the Venetian Senate created a new magistracy exclusively for enforcing sumptuary provisions, the Provveditori sopra le Pompe. This institution became permanent in 1514. See Chambers and Pullan, Venice, 177.

7. See for examples, Freudenberger, “Fashion, Sumptuary Law, and Business,” 137; and Baldwin, “Sumptuary Legislation and Personal Regulation,” 131. Greenfield tested the connection between the Protestant Reformation and sumptuary law in Nuremberg, but found no evidence to support this relationship. Sekora attributed the increased enactment of sumptuary law in this period to a “church/state rapprochement” and the takeover of sumptuary law enforcement from church courts in Protestant countries. See Sekora, Luxury, 60–61. Raeff attributed the changes in sixteenth-century sumptuary regulations to the newly shared “moral spiritual function” between church and state in Catholic areas and the relegating of luxury to the state in the Protestant areas of Germany. Raeff, The Well Ordered Police State, 82. However, some studies have disputed this connection. Alan Hunt noted that the connection with Protestantism was more convincing for “morals laws,” such as those on gambling or Sabbath observance, not for sumptuary laws particularly. However, he also noted that these studies focused almost exclusively on Protestant areas and that very little work had been done on the sumptuary laws issued during the Catholic Reformation. Hunt found this surprising, as he contends that, anecdotally, there were more Catholic sumptuary laws than Protestant. Given the copious quantities issued by the Italian city-states, this is probably true. Hunt, Governance of the Consuming Passions, xiii.

8. Isambert, Recueil général des anciennes lois françaises, 1:669 and 697–700.

9. January 1563, January 20, 1563, February 20, 1565, February 1566, and also January 12, 1573. There was also a 1629 law that regulated the table.

10. Shaw lists three enactments in the sixteenth century, 1550, 1551, and 1552, as well as one law in the seventeenth century in 1621. Shaw, “Sumptuary Legislation in Scotland,”90–96. There was also an additional sumptuary law on banqueting in 1581. Also see Acts of the Parliament of Scotland. For the texts of individual laws, see Acts of the Parliament of Scotland, 2:488, c. 22, 1551; A.P.S., 3:221, c. 19, 1581; A.P.S. 3:625, c. 17 and 18, 1621; A.P.S., 8:350, c. 80, 1681. Hunt lists a total of twelve laws for Scotland in the sixteenth century. Hunt, Governance of the Consuming Passions, 29, 32.

11. Fontanon, Les édicts et ordonnances des rois, 3:918–920, arts. 2 and 3.

12. Ibid., 2:918–919, arts. 2 and 3. Unfortunately the texts of several of these laws have been lost. See also January 12, 1573, ibid., 4:1240–1241.

13. Verga, “Le leggi suntuarie,” 54.

14. Newett, “The Sumptuary Laws of Venice,” 273.

15. October 8, 1562: reproduced in Chambers and Pullan, Venice, 179.

16. Verga, “Le leggi suntuarie,” 54.

17. Chambers and Pullan, Venice, 179.

18. Isambert, Recueil général des anciennes lois, 16:264, art. 134.

19. May 31, 1517: Hughes and Larkin, Tudor Royal Proclamations, 1:128–129, no. 81.

20. See, for example, Elizabeth’s proclamation of March 9, 1571: Hughes and Larkin, Tudor Royal Proclamations, 2:381–182, no. 601.

21. May 31, 1517: Hughes and Larkin, Tudor Royal Proclamations, 1:128–129.

22. Ibid., 128.

23. A.P.S., 1551, c. 22, 2:488; Shaw, “Sumptuary Legislation in Scotland,” 90.

24. Reproduced in Vincent, Costume and Conduct, 33.

25. Greenfield, “Sumptuary Law in Nürnberg,” 57.

26. Ibid.

27. Vincent, Costume and Conduct, 21.

28. Spices were often used in early modern medicine as drugs. It is very likely that legislators felt they needed to specify all possible uses of spices because diners often evaded sumptuary laws by “renaming” illegal items.

29. A.P.S., 1581, III, c. 19, 221.

30. A.P.S., 1627, c. 17 and 18, 625, act. 25.

31. A.P.S., 1681, c. 80, 8, 350.

32. 1485: Greenfield, “Sumptuary Law in Nürnberg,” 58.

33. Vincent, Costume and Conduct, 32.

34. Ibid., 33.

35. Roper, “Going to Church and Street.”

36. Vincent, Costume and Conduct, 35.

37. Greenfield, “Sumptuary Law in Nürnberg,” 60.

38. Vincent, Costume and Conduct, 21.

39. Ibid., 27.

40. Rolland, Remonstrances, 27.

41. Ibid., 142.

42. Poncet, Remonstrance à la noblesse de France, 13.

43. Rolland, Remonstrances, 130.

44. Crom?, Dialogue d’entre le malheustre, 72.

45. Rolland, Remonstrances, 130.

46. See, for example, Albala, “To Your Health,” for restrictions on wine.

47. Galen, “On the Cause of Diseases,” in Grant, Galen on Food and Diet, 51.

48. Albala, Eating Right in the Renaissance, 25, 30.

49. Ibid., 104. Albala notes that the authors who wrote between 1530 and 1570 were particularly critical of gluttony; see 32–33.

50. Galen, “On the Cause of Diseases,” 51.

51. Galen, “On the Powers of Foods,” 154.

52. Albala, Eating Right in the Renaissance, 40; see also 64–79.

53. Ibid., 68, 81.

54. Galen, “On the Powers of Foods,” 155. Galen suggested that his patients eat pork.

55. Albala, Eating Right in the Renaissance, 80–81.

56. Ibid.

57. Ibid., 144–147.

58. Ibid., 106.

59. Joannitius, “Bloodletting”: A Sourcebook in Medieval Science, ed. E. Grant (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), 800.

60. Rolland, Remonstrance, 227.

61. The notion that the physical body reflected the state of the soul was fairly common in the Reformation, as was the use of an opponent’s weight to criticize his spirituality. Lyndal Roper recently noted that Protestants regularly lampooned overweight popes and bishops. Images of Luther, on the other hand, depicted his large body as a sign of the rightness of his beliefs and “was central to his rejection of Catholic asceticism. See Lyndal Roper, “Martin Luther’s Body: The ‘Stout Doctor’ and His Biographers,” American Historical Review 115 (2010): 351–384.

62. For a discussion of the relationship between nutritional theory and the growth of the early modern state, see Albala, Eating Right in the Renaissance, 217–240.

63. Ibid., 241.

64. Ibid., 233.

65. See, for example, François de La Noue, Discours politiques et militaires (Genève: Droz, 1967 [1580]), 31.

66. Laffemas, Advis sur l’usage.

67. La Noue, Discours politiques, 785.

68. Laffemas was obsessed with the idea of developing a domestic luxury industry and ended the export of gold and silver to pay for foreign luxuries. See his Les tresors et richesses. For a discussion of mercantilist policies in this period, see the classic treatment by Cole, French Mercantilist Doctrine.

69. Laffemas, Les tresors et richesses, 18.

70. Ibid.

71. Laffemas, Le Merite de travail et labeur, 12.

72. See Laffemas, Les tresors et richesses, 18, 21, Le Merite de travail et labeur, 12; Advis sur l’usage, 71.

73. Several authors of the treatise against luxury of both religions blamed luxury on the nobility and noted that their pursuit of luxury and wealth led them to “abuse peasants” and become involved with the French Civil Wars. La Noue, Discours politiques, xxvi–xxvii.

74. See, for example, Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe.

75. Mentzer, “Fasting, Piety, and Political Anxiety,” 333–334.

76. Ibid., 340.

77. Ibid., 339–340.

78. February 20, 1565: Fontanon, Les édicts et ordonnances, 1:943.

79. Henry VIII issued three proclamations dispensing with Lenten fasts because he claimed there was a shortage of fish. See, for example, March 11, 1538: Hughes and Larkin,Tudor Royal Proclamations, 1:260–262, no. 177. Beginning with Edward VI, Lenten proclamations enforced abstinence from meat. Edward issued three such proclamations. See, for example, March 9, 1551: Hughes and Larkin, Tudor Royal Proclamations, 1:510–512, no. 368. Elizabeth I issued seventeen proclamations enforcing Lenten fasts; see, for example, January 14, 1600, Hughes and Larkin, Tudor Royal Proclamations, 3:204–209, no. 800. This pattern continued under the Stuart monarchs in the seventeenth century.

80. January16, 1548: Hughes and Larkin, Tudor Royal Proclamations, 1:413, no. 297; and A. Luders, T. E. Tomlins, J. Raithby, eds., Statutes of the Realm (London, 1810–1828), vol. 4, pt. 1, 2° and 3° Edw. VI c. 19, 1548.

81. See, for example, Mack P. Holt, “Europe Divided. Wine, Beer, and the Reformation in Sixteenth-Century Europe,” in Mack P. Holt, ed., Alcohol: A Social and Cultural History (Oxford: Berg, 2006), 25–40.

82. Ibid., 37.