Newcomers to Georgia need not worry about entering a cultural wasteland. If you like fine art, you can find it at the many museums in the state, including the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Morris Museum in Augusta, and the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah. If you like folk art and crafts, you came to the right place. Folk art by Howard Finster and pottery by the Meaders family may be admired or purchased, if you’re willing to pay handsomely.

You’ll hear music everywhere in the state, from blues to bluegrass, from Handel to hip-hop. To get an idea of Georgia’s musical history, take a trip to Macon and browse the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, where you can hear the works of Ray Charles, James Brown, Blind Willie McTell, Johnny Mercer, and other native sons.

Theater is alive and well in Georgia, too. The Alliance Theatre in Atlanta is the largest regional theater in the Southeast, and Atlanta’s restored Fox Theatre brings in touring Broadway plays.

Other cities have vibrant community theater and restored movie palaces that now host live performances. The 1921 Lucas Theatre in Savannah was saved from oblivion by community activists and reopened in 2000. The Historic Savannah Theatre has been transformed and refurbished as a venue for local and touring performances. Columbus is home to the famous Springer Opera House, a 137-year-old facility that is the official State Theater of Georgia. In 1964, it, too, was saved by community efforts and restored to its 1871 Edwardian glory. Also in Columbus is the Liberty Theatre, the city’s first black theater when it opened in 1924. The Liberty has hosted Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, and other renowned black performers. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it now hosts arts performances for all audiences.

Other historic theaters in Georgia that have avoided the wrecking ball are the 1921 Rylander in Americus, the 1920s Douglass Theatre and the 1884 Grand Opera House in Macon, the 1910 Morton Theatre in Athens, the 1916 Imperial Theatre in Augusta, the 1945 Holly Theatre in Dahlonega, the 1940 Historic Elbert Theatre in Elberton, the 1941 Wink Theatre in Dalton, the 1929 DeSoto Theatre in Rome, and the 1930 Grand Theatre in Cartersville.

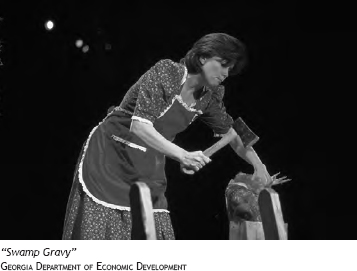

Three must-see performances are Swamp Gravy, the state’s official folklife play, which runs from July to October in Colquitt; Heaven Bound, an African-American folk drama, performed in Atlanta; and Cotton Patch Gospel, a musical translation of the New Testament, performed in various venues.

Traditional crafts such as weaving, woodcarving, and quilting are flourishing in Georgia. Visitors can see demonstrations at various craft fairs and at the Foxfire Museum and Heritage Center in Rabun County.

The literary scene in Georgia has undergone remarkable growth since Margaret Mitchell put Atlanta on the map with Gone With the Wind. New writers, both natives and newcomers, are adding to the legacy of Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers, and Erskine Caldwell. Each year, more than 50,000 people attend the Atlanta Journal-Constitution Decatur Book Festival to hear regional talent, as well as some of the nation’s major authors.

The following is a sample of what Georgia has to offer in the way of arts and entertainment. You’ll find much more to enjoy, depending on the part of the state where you live.

Georgia’s music is as diverse as its population, and has been for nearly 200 years. Before the Civil War, Georgians basically had the same taste as other Americans. They attended classical music concerts, operas, and gospel singings. In rural Georgia, Sacred Harp, a form in which the singers’ voices “shaped” the notes, was popular.

Today, you can find any type of live music in most of the larger cities. The Atlanta Symphony became one of the leading orchestras in the country after Robert Shaw was named director in 1967. Atlanta also has several music clubs for local and regional performers, from blues to rock. Atlanta’s Chastain Park, an open-air arena featuring tables for candlelight dining, is a popular site for touring musical acts.

Country Music

Folk music had always been around, but it became overshadowed in 1927 by something called “country music” after Victor Records set up a recording studio in Bristol, Tennessee, and invited area musicians to come in. In addition to Jimmy Rodgers and the Carter Family, a Georgia cotton mill worker, Fiddlin’ John Carson, made a recording. Carson’s record became such a success that the company sought other performers in a similar style.

Georgia native Ray Charles is not known as a country artist, but his 1992 record, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, brought this type of music to a broader audience. Other nationally known singers from Georgia include Bill Anderson of Commerce, Brenda Lee of Lithonia, Ronnie Milsap of Young Harris, Travis Tritt of Marietta, Trisha Yearwood of Monticello, Ray Stevens of Clarksdale, Doug Stone and Alan Jackson of Newnan, and Jerry Reed of Atlanta. Reed was probably best known for his acting role as Burt Reynolds’s sidekick in the Smokey and the Bandit movies.

Boudreaux Bryant of Moultrie and his wife, Felice, were one of the most successful songwriting teams in country music. Their hits included “Rocky Top” and several Everly Brothers songs.

Rhythm-and-Blues

Mississippians would argue otherwise, but Georgia can also claim to be the birthplace of the blues. An English visitor in 1839 first made reference to the rice-plantation slave songs and music that later would be called “the blues.” Wherever the genre was born, Georgia is the home of some of the greatest blues artists.

Gertrude “Ma” Rainey of Columbus is said to have been the first to sing blues in vaudeville, around 1900. Also around that time, blues musicians Georgia Tom Dorsey of Villa Rica, Piano Red (William Perryman) of Hampton, and others performed in clubs in Atlanta. Blind Willie McTell of Thomson was a well-known blues singer who performed in Atlanta from the 1920s until the 1950s. He was often joined by Piano Red and Curley Weaver of Covington.

Beginning in the late 1950s, rhythm-and-blues artists such as Chuck Willis, Ray Charles, Little Richard, and James Brown became nationally known.

Willis—best known for the hit song “What Am I Living For?”—also composed songs for Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley.

Ray Charles of Albany was a recording star in several fields, including rhythm-and-blues, country, gospel, and pop. His first big hit, “I Got a Woman,” was recorded in Atlanta. Anyone who has seen Ray, the film about Charles, knows that the musician overcame blindness, poverty, drug addiction, and racial discrimination to become an icon.

Little Richard (Richard Penniman) is an over-the-top showman from Macon. His 1950s songs such as “Long Tall Sally” and “Tutti-Frutti” became hits on the rock-’n’-roll charts.

Perhaps the most influential rhythm-and-blues singer was James Brown of Augusta. Proclaimed “the Godfather of Soul” and “the hardest-working man in show business,” Brown was a dynamic stage performer whose biggest hits included “Please, Please, Please,” “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” and “I Got You (I Feel Good).”

Another great R&B singer who crossed over to popular music was Otis Redding, born in 1941 in Dawson. Redding grew up in Macon, where he was influenced by Little Richard and Sam Cooke. Two of his biggest hits were “Try a Little Tenderness” and “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay.” He was killed in a plane crash in 1967.

Another famous Georgia R&B and soul performer is Atlanta native Gladys Knight, who recorded the 1973 classic “Midnight Train to Georgia” with her backup singers, the Pips. And beach music lovers still remember the 1960s group The Tams for “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am).” Joseph and Charles Pope, Robert Lee Smith, and Horace Kay formed the group in Atlanta in the 1950s and were joined later by Floyd Ashton.

One of the newest stars in rhythm-and-blues is Usher, who was born Usher Raymond in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1978 but moved to Atlanta with his mother in 1990. He has sold millions of albums since signing with LaFace Records. His debut album was the self-titled Usher.

Swing

Johnny Mercer of Savannah was one of the most famous songwriters during the “swing” period of Big Band music. Mercer wrote more than 1,000 songs, many of them for Hollywood movies. He won Academy Awards for “Moon River,” “Days of Wine and Roses,” “In the Cool, Cool, Cool of the Evening,” and “On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe.”

Lena Horne was born in Brooklyn, but the famous singer and actress spent part of her childhood in Fort Valley and Atlanta. Best known for the 1943 song and film Stormy Weather, Horne performed in other films and Broadway musicals and was active in the civil-rights movement.

Harry James, one of the top trumpet players and Big Band leaders of the ’30s and ’40s, was born in Albany in 1916. He appeared in several Hollywood films and was married to the actress Betty Grable.

Joe Williams, a jazz vocalist born in Cordele in 1918, performed with Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, and Earl Hines and won several awards as a solo artist. Later in his career, he appeared on television in The Cosby Show as Claire Huxtable’s father.

Rock and Pop

Phil Walden’s Capricorn Records in Macon was responsible for introducing Southern rock music when he signed the Allman Brothers Band in 1969. Chuck Leavell, a pianist and keyboard player with the band, later performed with the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton. In 1972, a group of musicians in Doraville formed the Atlanta Rhythm Section and continued the tradition of Southern rock.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Athens was the birthplace of three popular bands: the B-52s, R.E.M., and Widespread Panic.

The women of the B-52s sported beehive hairdos, and the band dressed in funky outfits. One of its biggest hits was “Love Shack.”

R.E.M., one of the most critically acclaimed rock bands in the country, was formed in 1980 when University of Georgia student Michael Stipe got together with Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Bill Berry to rehearse at an abandoned church in Athens. The rest is history. The Grammy Award–winning group has sold more than 70 million records, including the hit single “Losing My Religion.” Drummer Bill Berry left R.E.M. in 1995 after suffering a brain aneurysm onstage.

Widespread Panic was formed in 1982 by University of Georgia students John Bell and Mike Houser. They later added bassist Dave Schools and began recording music that was a blend of jazz, Southern rock, and blues.

In the late 1980s in Atlanta, Amy Ray and Emily Saliers formed a pop-rock duo called the Indigo Girls. After gaining national prominence in 1989 with their self-titled album, “Indigo Girls,” they won a Grammy in 1990.

Rap and Hip-Hop

Atlanta has become what some consider the new Motown because of its booming rhythm-and-blues, hip-hop, and rap recording industry. One of the first studios was LaFace Records, founded by Antonio “L.A.” Reid and Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds in New York but later relocated to Atlanta. LaFace has recorded artists such as Usher, OutKast, TLC, and Toni Braxton.

Jermaine Dupri added to Atlanta’s reputation as a music town when he formed So So Def Records in 1992 after writing and producing songs for the rap group Kriss Kross. He signed the Atlanta group Jagged Edge in 1998 and rapper Lil’ Bow Wow in 2000.

When it comes to men and women who produce fine art, Georgia has very few who are nationally known.

Lamar Dodd (1909–1996), who was head of the University of Georgia Art Department, is considered the state’s most influential artist. Dodd’s paintings explore both outer space and inner space. In 1963, he began a series of impressionist paintings of the moon, the sun, and the universe. In the 1970s, he looked inward to produce paintings of the human heart. Later, he returned to landscapes, then began painting more violent contemporary subjects, such as the bloody glove from O. J. Simpson’s murder trial.

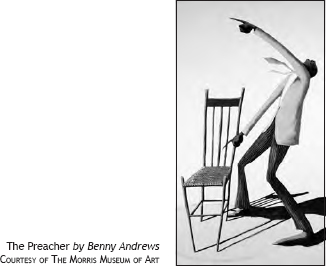

Benny Andrews (1930–2006) was another Georgia artist with a national reputation. The brother of writer Raymond Andrews, he grew up in rural Morgan County, studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, and settled in New York. Even in the North, Andrews’s childhood memories influenced most of his work. Using collages, Andrews created expressionistic three-dimensional works depicting different elements of African-American life. After receiving a John Hay Whitney Fellowship in 1965, Andrews returned to Georgia, where he created his Autobiographical Series. His works have been exhibited in New York, Philadelphia, and other major cities. In 1969, he cofounded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition to help get recognition for minority artists.

Although some Georgians collect fine art and appreciate traveling exhibitions of the Great Masters of Europe, more of us are fans and collectors of folk art, or art created by self-taught artists.

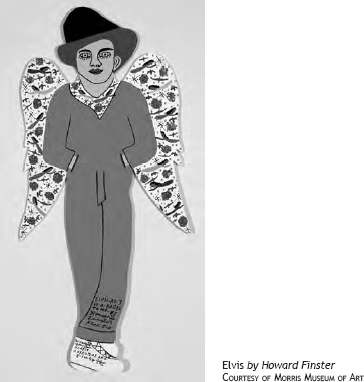

The most famous folk artist in Georgia is the late Howard Finster (1915–2001), a Baptist minister who was working at a bicycle shop in Pennville when he reported having a vision. In response to the vision, he began creating Paradise Garden, an outdoor collection of sculptures made from plywood, concrete, and bicycle parts. Some were humorous, while others had religious themes. In 1976, he was painting a bicycle when he saw a face in the paint on his fingertip. That was a sign, he believed, to begin painting sacred art. And he did, producing thousands of paintings and becoming famous enough to be invited on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. He later worked with the rock group R.E.M. on album covers. Some of his work is on permanent display at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. And his Paradise Garden is still open to tourists.

St. EOM (1908–1986), born Eddie Owens Martin, was another self-taught artist in the visionary style of Finster. Martin was the creator of Pasaquan, a series of buildings in Maron County painted inside and out with vividly colored human figures and natural images. Martin began his project after he had visions of futuristic messengers from a place called Pasaquan. The messengers told him to paint a peaceful future for the world. Calling himself St. EOM, he began the art site in 1955 with a 19th-century farmhouse and other buildings on a seven-acre site. Though Martin committed suicide in 1986, Pasaquan remains open to the public. His work is on display at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and the Albany Museum of Art.

Nellie Mae Rowe (1905–1982) was an African-American folk artist who achieved a national reputation for her colorful drawings in crayon, her sculptures made of dried chewing gum, her plastic flowers, and her works using recycled objects such as egg cartons. Her work can be seen at the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.

The Albany Museum of Art (www.albanymuseum.com) features one of the largest collections of African art in the South.

Brenau University Galleries (www.brenau.edu/discover/galleries), located on the campus of Brenau University in Gainesville, has a permanent collection that includes works by William Merritt Chase, Jasper Johns, Renoir, Cezanne, and Delacroix.

Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries (http://www.cau.edu/art_gallery/art_gal_dir.html) has a large collection of art by African-Americans.

The Columbus Museum (www.columbusmuseum.com) focuses on fine and decorative art by artists such as Gilbert Stuart, Robert Rauschenberg, Lamar Dodd, and Benny Andrews.

The Georgia Museum of Art (www.uga.edu/gamuseum/) at the University of Georgia is the official museum of the state. The permanent collection includes Italian Renaissance paintings and American paintings by artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Winslow Homer, and Jacob Lawrence.

The High Museum of Art (www.high.org) in Atlanta has a permanent collection of works by American artists, decorative arts, European paintings, photography, African art, and folk art. Other exhibitions have included the impressionists and works from the Louvre.

Lamar Dodd Art Center (www.Lagrange.edu/academics/art/Lamar-Dodd.htm) at LaGrange College features a permanent exhibit of Dodd’s work, as well as American Indian art and 20th-century photography.

Marietta/Cobb Museum of Art (www.Mariettacobbartmuseum.org) features 19th- and 20th-century American art. Exhibitions have included works by regional artists, Winslow Homer, and the Wyeth family.

The Michael C. Carlos Museum (www.carlos.emory.edu) at Emory University in Atlanta has an extensive collection of art and artifacts from the ancient world. In addition to objects from Egypt, Greece, and Rome, the museum exhibits works from Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

The Morris Museum of Art (www.Themorris.org) in Augusta opened in 1992. Its primary focus is Southern art. Paintings from the antebellum period to the present provide a visual history of art in the South. Exhibits include works by Benny Andrews, Lamar Dodd, Nellie Mae Rowe, Jasper Johns, and Henry Ossawa Tanner.

The Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia (www.mocaga.org), located in Atlanta, houses works created by artists who were born in Georgia or who moved to the state. Featured artists include Benny Andrews, Radcliffe Bailey, Howard Finster, and Nellie Mae Rowe.

The Oglethorpe University Museum of Art (http://museum.oglethorpe.edu/) in Atlanta has hosted exhibitions of works from Spain, Venice, South Africa, and China. “Mystical Arts of Tibet Featuring Personal Sacred Objects of the Dalai Lama” opened here for the 1996 Olympics.

The Quinlan Visual Arts Center (www.quinlanartscenter.org) in Gainesville houses a permanent collection of works by local and internationally known artists. Featured artists include Ed and Lamar Dodd, Dennis Campay, Geoffrey Johnson, and Roseta Santiago.

The Spelman College Museum of Fine Art (www.spelman.edu/museum/index.shtml) in Atlanta has exhibits focusing primarily on contemporary African and African-American works by women.

The Telfair Museum of Art (www.Telfair.org) in Savannah has a permanent collection that includes American impressionist paintings by George Bellows, Robert Henri, and Childe Hassam. It also has an exhibit of 19th-century decorative arts and neoclassical furniture.

The Tubman African American Museum (www.Tubmanmuseum.com) in Macon features an extensive collection of African-American art and artifacts. One of the showcased paintings is From Africa to America, a mural by Macon artist Wilfred Shroud that depicts important events in African-American history.

Early Georgians began crafting objects from wood, clay, and fiber for reasons of necessity rather than art. Pottery was used for milk and water containers; quilts and bedspreads were crafted for warmth; wooden baskets and tools were made for use on the farm. As these craftsmen and craftswomen honed their workmanship, they began to create more artistic designs.

The Civil War forced many families who bought these items from factories to return to making their own. After the war, many Georgians, particularly in the mountains in the northern part of the state, began selling handcrafted items for profit.

Today, travelers on the Georgia backroads are likely to find quilts, chenille bedspreads, wooden toys, and pottery for sale at markets and roadside stands.

Fiber Crafts

Georgians have practiced spinning and weaving since the early 1800s. Rural folk and even some of the wealthier Georgians wore homespun clothing made from flax, wool, and cotton. They made dyes from walnuts, red clay, and plants such as indigo, which produced a deep blue color. The art is still practiced today by members of the Chattahoochee Handweavers Guild and other organizations.

Quilting is more popular than ever, thanks to community quilting bees, quilting clubs, and classes. Two of Georgia’s most famous quilters were former slave Harriet Powers of Athens and Talula Gilbert Bottoms of Fayette County. Many of Powers’s quilts were designed around Bible stories.

In the 1890s, Catherine Evans Whitener of Dalton popularized the technique of tufting cotton sheeting with designs of thick yarn. In French, chenille means “caterpillar.” Displays of chenille bedspreads were once a familiar sight along U.S. 41. Such bedspreads still can be found in stores around Dalton.

Pottery

Pieces of Georgia pottery, once created for practical uses around the farm, are now works of art selling for hundreds of dollars. The Meaders family was the first to capitalize on the market of tourists and collectors by creating colorful, artistic pieces. Lanier Meaders (1917–1998) of Cleveland improved on his parents’ process and began creating jugs with faces. Members of the family still carry on the tradition today. Other folk potters are Michael and Melvin Crocker of Lula and Linda Craven Tolbert of Cleveland. For examples of the many kinds of Georgia pottery, visit the Folk Pottery Museum (www.Folkpotterymuseum.com) in Sautee Nacoochee.

Basket weaving is an art still practiced in many parts of Georgia. In the mountains, craftsmen use split white-oak strips as their weaving material. Along the coast, some weavers continue the tradition of the rice plantation slaves by using grasses. Others follow the example of Mrs. M. J. McAfee of West Point and use pine needles. Still others use honeysuckle vines or willow branches.

Various items carved from wood can be found at craft fairs and markets. One of the most popular is the walking stick. On the coast, carvers Arthur “Pete” Dilbert of Savannah and James Cooper of Yamacraw were influenced by the African-American tradition of carving figures of reptiles and human faces into canes.

Nearly every large city and many small towns in Georgia have community theaters.

Atlanta is the home of the Alliance Theatre, the largest regional theater in the Southeast. Several plays that debuted at the Alliance have gone on to be performed on Broadway. These include Driving Miss Daisy by Alfred Uhry, a musical version of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, and Elaborate Lives: The Legend of Aida, a musical by Elton John and Tim Rice that later won four Tony Awards. Touring Broadway shows also come to town on a regular basis at the historic Fox Theatre and other venues.

The official state folklife play is Swamp Gravy, performed from July to October in Colquitt. Cowritten by Joy Jinks and Richard Owen Geer, Swamp Gravy was named after a southwestern Georgia soup made from onions, tomatoes, potatoes, and drippings left over from fried fish. The play is a multiracial musical based on stories by and about residents of Miller County. Each year, new stories are added.

Other communities, inspired by Swamp Gravy, have begun producing their own folk plays. In 2007, the Sautee Nacoochee Community Association in the North Georgia town of Sautee used local actors to perform stories about the region in Headwaters: Stories from a Goodly Portion of Beautiful Northeast Georgia. The next year, the folklife play Land of Spirit premiered in Lavonia. The play is made up of true stories about the people and places of northeastern Georgia. In South Georgia, the community of Lyons sponsors Tales from the Altamaha during the Vidalia Onion Festival each spring. The production is based on stories by the late colonel T. Ross Sharpe, an author of local color and humor. Plays such as Swamp Gravy, Headwaters, Land of Spirit, Tales from the Altamaha, the Social Circle Theater’s Stories from the Well, and coastal Camden County’s Crooked Rivers not only entertain, they reveal bits of history about the communities. Crooked Rivers, for example, focuses on fishermen, farmers, and the people living and working on the rivers of the coast.

The previously mentioned plays are relatively new, but some performances have been around so long they are traditions. Heaven Bound is a popular African-American folk drama featuring spirituals by a black choir. The play premiered at Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Atlanta in 1930 and toured the South during the Great Depression. The story depicts a group of black pilgrims on a journey to heaven. Satan leads them astray before clashing with a pilgrim at the end. Heaven Bound still plays to packed audiences every year.

Cotton Patch Gospel is another popular musical that is performed regularly. It is based on Southern Baptist minister Clarence Jordan’s folksy version of the Gospels of Matthew and John. Atlanta actor Tom Key and stage director Russell Treyz wrote the music in collaboration with songwriter Harry Chapin. In the play, the mother of Jesus is Mary Hagler, daughter of a Baptist deacon. Jesus is born in an abandoned trailer behind Dixie Delite Motor Lodge during Mary and Joseph’s trip to Atlanta for an income-tax audit. Instead of being crucified, Jesus is lynched by the Ku Klux Klan after being sentenced by Georgia governor Pilate.

Georgia does not have the literary heritage of Mississippi or North Carolina, but it has produced more than its share of famous writers. Few people in the country—or the world, for that matter—have not heard of Margaret Mitchell and Gone With the Wind. And any reader who loves Southern literature is familiar with Flannery O’Connor, Erskine Caldwell, Carson McCullers, James Dickey, and Pat Conroy.

Our former president, Jimmy Carter, has written several books—including his memoir, An Hour Before Daylight, and a historical novel, The Hornet’s Nest—that are not only entertaining but also informative about life in Georgia from the Revolutionary War to the present.

In addition to homegrown talent, Georgia has become a magnet for writers from other states and countries. Ha Jin, who was born in China, wrote some of his best novels while teaching at Emory University. Now, Salman Rushdie, the author of the controversial novel The Satanic Verses, is a visiting professor at Emory.

The following are some of the state’s major writers, living and dead, whose work will better acquaint you with what life used to be like in Georgia and what it’s like now. These are not all of our important writers, by any means. It would take an entire book to include everyone. But this list is a good place to start. Ask your local librarian or bookseller for other recommendations.

Conrad Aiken (1889–1973): A former poet laureate of Georgia, Aiken was one of the country’s major literary figures. He received a Pulitzer Prize for Selected Poems (1929) and a National Book Award for Collected Poems (1953). Born in Savannah, Aiken lived through a nightmare that greatly affected his personal and literary life. His father, a prominent doctor, shot and killed his wife and then killed himself. Aiken describes his psychological trauma and offers insights about his literary odyssey in his autobiography, Ushant (1952).

Raymond Andrews (1934–1991): The son of sharecropper parents, Andrews was the author of several critically acclaimed novels about African-American life in Georgia. His debut novel, Appalachee Red, won the James Baldwin Prize for fiction in 1979. Andrews was born in the community of Plainview near Madison. His Muskhogean trilogy chronicles black life in the South between World War I and the 1960s. The first of the series, Appalachee Red, was followed by Rosiebelle Lee Wildcat Tennessee (1980) and Baby Sweet’s (1963). Andrews’s memoir, The Last Radio Days (1990), describes his childhood with his black grandmother and white grandfather.

Tina McElroy Ansa (1949–): Ansa, a former journalist for the Atlanta Constitution, has staked out her native Macon as the setting for her fictional town of Mulberry. The supernatural elements of African-American life are a common thread in her novels. In her debut novel, Baby of the Family (1989), a child is born with a caul, or membrane, covering her head. According to folklore, such a child is endowed with the ability to see ghosts. Her other novels are Ugly Ways (1993), The Hand I Fan With (1996), and You Know Better (2002).

Vereen Bell (1911–1944): A native of Cairo, Georgia, Bell had just begun a successful literary career when he was killed in action in World War II. He wrote a number of stories and magazine articles, but his best-known work is Swamp Water (1940), a novel set in the Okefenokee. This story of a young man’s friendship with a fugitive was the basis for a 1942 Hollywood film. His other novel, Two of a Kind (1943), was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post.

Roy Blount, Jr. (1941–): Blount is a Decatur native who has a national reputation as an author and humorist who can explain the oddities of the South to folks who don’t live here. He is the author of Crackers: This Whole Many-Angled Thing of Jimmy, More Carters, Ominous Little Animals, Sad-Singing Women, My Daddy and Me (1980) and a memoir, Be Sweet: A Conditional Love Story (1998). Blount is also a national magazine columnist and a regular guest on the radio show A Prairie Home Companion.

David Bottoms (1949–): The current poet laureate of Georgia, Bottoms is a writer whose works often deal with death, nature, and religion in the South. Born in Canton, Bottoms began writing poems at an early age. At 29, he won the 1979 Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets for his collection Shooting Rats at the Bibb County Dump (1980). His other notable poetry collections include In a U-Haul North of Damascus (1983) and Vagrant Grace (1999).

Olive Ann Burns (1924–1990): Burns, a native of Banks County, did not take fiction writing seriously until she was diagnosed with cancer in 1975. Previously, she had worked as a staff writer and columnist for the Atlanta Journal and Constitution’s Sunday magazine, but she quit to raise a family after she married fellow journalist Andrew Sparks. Drawing on her family’s history, she wrote Cold Sassy Tree (1984), the coming-of-age story of a young boy whose grandfather shocks everyone by remarrying three weeks after his wife dies. The sequel, Leaving Cold Sassy, was published posthumously in 1992.

Erskine Caldwell (1903–1987): Caldwell is one of Georgia’s greatest writers, although some Southerners have never forgiven him for Tobacco Road (1932) and God’s Little Acre (1933), novels sharply critical of race and class and controversial because of their sexual content. Even so, some critics have declared Tobacco Road one of the 100 most significant novels of the 20th century. During his career, Caldwell produced 25 novels, 12 nonfiction books, and numerous short stories. One of his most important nonfiction books was You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), a portrait of country people during the Depression; Caldwell’s vivid writing accompanied Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs. Born in Coweta County, Caldwell was the son of a schoolteacher and an Associate Reformed Presbyterian minister. His father’s passion for social reform was a major influence. Caldwell’s autobiography, With All My Might, was published shortly before his death in 1987.

Brainard Cheney (1900–1990): Cheney was a member of an elite group of writers that included Flannery O’Connor, Robert Penn Warren, Caroline Gordon, Alan Tate, and Andrew Lytle. Born in Fitzgerald, Cheney attended Vanderbilt University, where he became friends with the Fugitive and Agrarian writers. His novels—Lightwood (1939), River Rogue (1942), This Is Adam (1958), and Devil’s Elbow (1969)—depict social and racial changes occurring in South Georgia.

Pearl Cleage (1948–): Cleage is an African-American writer whose works deal with civil rights, women’s rights, and the black experience. Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, she moved to Atlanta to attend Spelman College. Cleage’s debut novel, What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day, was a 1988 Oprah Book Club selection. Her other novels include I Wish I Had a Red Dress (2001), Some Things I Thought I’d Never Do (2003), and Babylon Sisters (2004). One of her best-known nonfiction works is Mad at Miles: A Black Woman’s Guide to Truth (1990), a criticism of musician Miles Davis’s treatment of women and male abusive behavior in general.

Pat Conroy (1945–): Born in Atlanta, Conroy has set most of his works on the South Carolina coast. His memoir The Water Is Wide (1972) is about the year he spent teaching black students on Daufuskie Island. The Great Santini (1976) is a semi-autobiographical portrait of his father, a United States Marine Corps pilot; The Lords of Discipline (1980) is set at his alma mater, the Citadel; and The Prince of Tides (1986) and Beach Music (1995) both take place mainly in the South Carolina Low Country. All except Beach Music have been made into movies. Conroy, who as a student was influenced by the works of Thomas Wolfe, creates a strong sense of place in his fiction while drawing on his personal experiences.

Harry Crews (1935–): A native of Bacon County, Crews has written eloquently about some of the more eccentric characters in the South. His novels include The Gospel Singer (1968), Naked in Garden Hills (1969), Car (1972), The Hawk Is Dying (1973), The Gypsy’s Curse (1974), A Feast of Snakes (1976), Scar Lover (1992), and An American Family: The Baby with the Curious Markings (2006). Crews’s memoir, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978), is a searing portrait of the dangers and hardships of rural life in Georgia in the late ’30s and early ’40s. In one near-death episode, Crews became ill with a fever that lasted six weeks and caused his legs to draw up severely. In another horrifying incident, he fell into a cast-iron pot of boiling water used to scald hogs and was burned over most of his body. A retired teacher at the University of Florida, Crews was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2001.

Janice Daugharty (1944–): Daugharty, who grew up in Echols County, has produced six novels and numerous short stories that reflect the culture and character of South Georgia. Her novels include Dark of the Moon (1994), Necessary Lies (1995), Earl in the Yellow Shirt (1997), and Like a Sister (1999). Most of her characters are residents of Cornerville, a fictional South Georgia town.

James Dickey (1928–1997): Dickey is considered one of Georgia’s greatest poets, but to most people he is best known as the author of Deliverance (1970). The novel and subsequent movie left a lasting—and unflattering—image of Georgia mountain folk. Born in Atlanta, Dickey joined the United States Army Air Corps in 1945 and received five Bronze Stars for his service as a navigator. He honed his skills as a poet while writing advertising copy for McCann-Erickson in Atlanta but eventually quit to teach. In 1968, he became professor and poet-in-residence at the University of South Carolina. Some of Dickey’s most memorable poems are “Looking for the Buckhead Boys,” “The Sheep Child,” “Cherrylog Road,” “Firebombing,” and “Falling.” Dickey was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2000.

Berry Fleming (1899–1989): Born in Augusta, Fleming left the South to attend Harvard and to live and write in New York. When he returned home nearly a decade later, he found a true story that would inspire his most popular novel, Colonel Effingham’s Raid (1943). The story, based on political corruption involving the Cracker Party in Richmond County, was adapted for a film starring Charles Coburn. Some of Fleming’s other novels include Siesta (1935), The Lightwood Tree (1947), The Winter Rider (1960), and The Affair at Honey Hill (1981).

Melissa Fay Greene (1952–): Greene is a Macon native whose critically acclaimed Praying for Sheetrock and The Temple Bombing focus on the civil-rights struggle in Georgia and the events that resulted. Praying for Sheetrock (1991) is a story of corruption in coastal McIntosh County in the ’70s and the clash between white politicians and black activists. The Temple Bombing (1996) is an account of the efforts of Rabbi Jacob Rothschild to bring African-American and white leaders together after his Atlanta temple is bombed and to convince his congregation to support civil rights.

Lewis Grizzard (1946–1994): Grizzard was a popular syndicated humor columnist who defended Southern traditions and wholeheartedly supported the University of Georgia Bulldogs. Born in Fort Benning, Grizzard grew up in Moreland, worked as a sports editor at several newspapers, and began writing a humor column for the Atlanta Constitution that was later syndicated in more than 400 publications. His columns and books were always a Southerner’s perspective on a changing world. His best-selling books include Elvis Is Dead and I Don’t Feel So Good Myself (1984) and Chili Dawgs Always Bark at Night (1989).

Anthony Grooms (1955–): Tony Grooms is an African-American writer whose work focuses on the effects of the civil-rights movement. His story collection, Trouble No More (1995), and his novel, Bombingham (2001), each won the Lillian Smith Book Award. In 2006, Trouble No More, a collection of stories about history, race, and the black middle class, was selected as the “Book All Georgians Should Read” by the Georgia Center for the Book.

Corra Harris (1869–1935): Although her name is unfamiliar to most Georgians today, Harris was a popular author during the early part of the 20th century. Born in Elbert County, she was a prolific novelist, essayist, and short-story writer whose works appeared in Harper’s and the Saturday Evening Post. The best known of her 19 novels is A Circuit Rider’s Wife (1910), the story of an itinerant preacher and his wife. The novel inspired the 1951 movie I’d Climb the Highest Mountain, which starred Susan Hayward.

Joel Chandler Harris (1845–1908): Harris earned his living as a newspaper editor, but his enduring legacy is his Uncle Remus folk tales. Born in Eatonton, Harris heard many of these stories while working as a printer at Turnwold Plantation and publishing a newspaper called The Countryman. After work, Harris would spend time in the slave quarters with Uncle George Terrell, Old Harbert, and Aunt Cissy as they recalled animal stories from Africa. The slave storytellers were inspirations for Uncle Remus and other figures when Harris began writing his tales of Br’er Rabbit and Br’er Fox. He later became associate editor of the Atlanta Constitution, working with Henry W. Grady chronicling the emergence of the New South. Harris’s first book of African tales, Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings—The Folklore of the Old Plantation, was published in 1880 and sold 10,000 copies.

Paul Hemphill (1936–): Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Hemphill is one of Atlanta’s most prolific journalists and authors. His subjects include sports, civil rights, country music, and the blue-collar world of truckdrivers. Some of his best-known works are Long Gone (1979), King of the Road (1989), Leaving Birmingham (2000), and Lovesick Blues (2005).

Mary Hood (1946–): Hood, a Flannery O’Connor Award winner for her collection of stories How Far She Went (1984), writes with a strong sense of the rural communities in both the mountain and coastal areas of Georgia. Born in Brunswick, she lived in a number of counties before settling in Jackson. Hood’s second collection of stories, And Venus Is Blue, won the Townsend Prize for fiction and the Lillian Smith Award. A recurring theme in Hood’s work is the effect urban development has on families and communities. Her first novel, Familiar Heat, was published in 1995.

Mac Hyman (1923–1963): Born in Cordele, Hyman was a promising young writer whose life was cut short by a heart attack before his second novel could be published. His debut effort, however, was a tremendous financial and critical success. No Time for Sergeants (1954), a story about a clueless farm boy from South Georgia who is drafted into the United States Air Force, became the basis for a television play, a Broadway play, and a film starring Andy Griffith. The international fame he received for No Time for Sergeants was so overwhelming that Hyman struggled to complete his second novel. Take Now Thy Son was published two years after his death.

Ha Jin (1956–): Ha Jin is the pen name of Xuefei Jin, a Chinese native who served in the army and was educated in China before coming to the United States in 1985. While an assistant professor of poetry at Emory University during the ’90s, Ha Jin wrote two volumes of poetry and three short-story collections. Ocean of Words: Army Stories (1996) won the PEN/Hemingway Award and Under the Red Flag (1997) won the Flannery O’Connor Award for short fiction. The novel Waiting (1999) won the National Book Award for fiction and the PEN/Faulkner Award. War Trash (2004) also won the PEN/Faulkner Award. His novel A Free Life (2007) is the story of an immigrant family that flees to Georgia after the Tiananmen Square massacre. Ha Jin now teaches at Boston University.

Greg Johnson (1953–): Johnson’s works focus on issues of the modern South. Born in San Francisco, he moved to Atlanta to earn his doctorate at Emory University. His first novel, Pagan Babies (1993), deals with the problems of growing up gay and Catholic in the time of AIDS. In addition to three books of short stories, he has written critical studies of Emily Dickinson and Joyce Carol Oates.

Tayari Jones (1970–): Jones is an African-American short-story writer and novelist whose works focus on Georgia and her hometown of Atlanta. She is a graduate of Spelman College and has a Master of Fine Arts degree from Arizona State University. Jones’s best-known novel is Leaving Atlanta (2002), a story of three children’s lives during the time of the crimes involving missing and murdered children in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Jones was a fifth-grade student in Atlanta at the time. The book won the Zora Neale Hurston/Richard Wright Foundation Legacy Award for debut fiction. Her second novel, The Untelling (2005), a story of a tragedy that disrupts the lives of a black middle-class Atlanta family, won the Lillian Smith Award.

Terry Kay (1938–): Born in Hart County, Kay is a former newspaper journalist and critic who began writing fiction in the mid-1970s after being encouraged by his friend Pat Conroy. His first book, The Year the Lights Came On (1976), is a semi-autobiographical novel about Kay’s childhood in rural northeastern Georgia. He followed that with After Eli (1981), a disturbing tale of an unscrupulous Irishman intent on seducing three women to get a fortune. His next novel, Dark Thirty (1984), is a dark tale of violence and revenge. Three of Kay’s novels—To Dance With the White Dog (1990), The Runaway (1997), and The Valley of Light (2003)—have been made into Hallmark Hall of Fame television shows. To Dance With the White Dog, a mystical story of a widower’s friendship with a dog that mysteriously appears shortly after his wife’s death, became an international bestseller. Kay was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2006.

James Kilgo (1941–2002): Kilgo was a University of Georgia professor known primarily for his collections of essays on hunting, nature, and man’s connection to wildlife. Deep Enough for Ivorybills (1988) and An Inheritance of Horses (1994) both reflected his wonder and appreciation for the natural world. He also wrote fiction. His novel, Daughter of My People, won the Townsend Prize for fiction. Born in Darlington, South Carolina, Kilgo spent most of his career at the University of Georgia. Although diagnosed with cancer in 2000, he decided to go on a hunting trip to Africa. His experiences were published shortly after his death in The Colors of Africa (2003).

John Oliver Killens (1916–1987): Born in Macon, Killens was an African-American writer whose novels deal with racism and the need for social change. He was a founder of the Harlem Writers Guild in New York in the early 1950s. His first novel, Youngblood (1954), is the story of black residents of a fictional Georgia community struggling for their rights during the Depression. His second novel, And Then We Heard the Thunder (1963), drew on his experiences as a black serviceman in World War II. Killens received numerous literary awards and was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.

Sidney Lanier (1842–1881): Born in Macon, Lanier was a poet whose works, written during Reconstruction, celebrated the natural world and the landscape of Georgia. His best-known poems include “Corn” (1875), “The Song of the Chattahoochee” (1877), and “The Marshes of Glynn” (1879).

Augustus Baldwin Longstreet (1790–1870): Longstreet was Georgia’s first major literary figure. He published Georgia Scenes, Characters, Incidents, Etc., in the First Half Century of the Republic in 1835. Born in Augusta, he was a man of many talents. In addition to writing fiction, he was a lawyer, judge, newspaper editor, minister, and college president.

Grace Lumpkin (1891–1980): Lumpkin, a Milledgeville native, was a radical crusader whose novels portray working-class struggles in the South during the Great Depression. To Make My Bread (1932) and A Sign for Cain (1935) are based on mill strikes in North Carolina and Alabama that erupted into violence.

Carson McCullers (1917–1967): Born in Columbus, McCullers has been ranked among the country’s major writers of the 20th century. Loneliness and isolation are recurring themes in her works. The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1940), The Ballad of the Sad Café (1941), Reflections in a Golden Eye (1943), and The Member of the Wedding (1946) have been adapted for films and Broadway plays. The Member of the Wedding ran for 501 performances on Broadway and won the New York Drama Critics Award.

Ralph McGill (1898–1969): As editor and publisher of the Atlanta Constitution during the civil-rights movement, McGill was the conscience of the South—a source of hatred for some and an inspiration for others. In his daily column, McGill was a voice of moderation, urging his fellow Southerners to end racial segregation after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the United States Supreme Court. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1959 for his columns on the bombing of the Jewish temple in Atlanta. These were reprinted in his book A Church, a School (1959). McGill also wrote about his life and the region in The South and the Southerner (1963).

James Alan McPherson (1943–): McPherson, a native of Savannah, became the first African-American to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction when he published Elbow Room (1977), a collection of stories. He is the recipient of several prestigious awards, including the MacArthur Fellowship. His other notable works include the story collection Hue and Cry (1968) and his memoir, Crabcakes (1998).

Caroline Miller (1903–1992): Miller, born in Waycross, became the first Georgian to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction when she published her novel, Lamb in His Bosom (1933). Set in South Georgia during the 19th century, the best-selling novel is the story of a woman’s two marriages and her struggle to overcome frontier hardships and the Civil War while giving birth to 14 children. The novel also won France’s Prix Femina.

Judson Mitcham (1948–): Mitcham, a native of Monroe, is a poet and novelist who writes about universal human emotions, using rural Georgia as a backdrop. One of his best-known poetry collections is Somewhere in Ecclesiastes (1991). Mitcham has won the prestigious Townsend Award for fiction twice for his novels The Sweet Everlasting (1996) and Sabbath Creek (2004). Like his poems, the novels deal with issues of race and class and the influence of an unchanging past on the present.

Margaret Mitchell (1900–1949): Peggy Mitchell of Atlanta published only one book in her lifetime, but what a book it was! Gone With the Wind (1936) won the 1937 Pulitzer Prize, introduced one of the most romantic couples in literature, inspired one of the greatest movies of all time, and became one of the best-selling books in the world. Mitchell, who worked for several years as a reporter for the Atlanta Journal’s Sunday magazine, began writing the novel to pass the time while recuperating from a broken ankle. Two sequels to Gone With the Wind have been penned by other authors, but Mitchell refused to write one herself. Incidentally, Mitchell’s famous heroine, Scarlett O’Hara, was initially called Pansy O’Hara.

Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964): A native of Savannah, O’Connor is considered Georgia’s greatest writer and one of the best fiction writers in America. Her darkly comic stories often feature eccentric or grotesque characters and are always shadowed by religion (O’Connor was a devout Catholic in the mostly Protestant South). Her best-known works are A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955), The Violent Bear It Away (1960), and Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965). Stricken with lupus in 1950, O’Connor moved to Milledgeville, where she lived until her death in 1964. Eight years later, The Complete Stories received the National Book Award.

Eugenia Price (1916–1996): Price was born in West Virginia but became famous as an author of historical novels after she moved to St. Simons Island. She meticulously researched the history of the Georgia islands to write her fictional St. Simons trilogy—The Beloved Invader (1965), New Moon Rising (1969), and The Lighthouse (1971)—and other novels set on the coast.

Janisse Ray (1962–): Ray is an environmentalist and author whose critically acclaimed Ecology of a Cracker Childhood is a mix of memoir and ecological message. Born near Baxley in Appling County, Ray was raised in her father’s junkyard and barred from watching television. Inspired by her father’s love of wildlife, she developed a passion for the vanishing longleaf pines that once forested the area. Ecology of a Cracker Childhood (1999) won the Southeastern Booksellers Award for nonfiction and the Southern Book Critics Circle Award. She continued to write about her life and her crusade to save the longleaf pine ecology in Wild Card Quilt: Taking a Chance on Home (2003) and Pinhook: Finding Wholeness in a Fragmented Land (2005).

Byron Herbert Reece (1917–1958): Reece, born in Union County, was an acclaimed poet and novelist whose brief but brilliant career ended tragically with his suicide. He supported himself by farming and teaching at Young Harris College. His poems, usually on the themes of nature, death, and religion, are written in a lyrical, ballad style. Two of his best collections are Ballad of the Bones and Other Poems (1945) and Bow Down in Jericho (1950), which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

Ferrol Sams (1922–): Sams—“Sambo” to his friends—had already enjoyed a long career as a physician in Fayette County when he decided to write about his Georgia boyhood. Run With the Horsemen (1982), published when he was 60, was the first of his novels featuring protagonist Porter “Sambo” Osborne, Jr. Liberally laced with humor, Sams’s novels are an entertaining and accurate portrait of life in rural Georgia before and after World War II. Sams was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2007.

Bettie Sellers (1926–): A former poet laureate of Georgia, Sellers lives in Young Harris, where she continues to write about the people of southern Appalachia. Her collections of poetry include Spring Onions and Cornbread (1978), Morning of the Red-Tailed Hawk (1981), Liza’s Monday and Other Poems (1986), and Wild Ginger (1989).

Celestine Sibley (1914–1999): Sibley was a journalist and author whose personal columns in the Atlanta Constitution revealed as much about Southern culture as they did about her family life. Born in Holley, Florida, Sibley became a columnist after working as a reporter covering some of Georgia’s most sensational criminal trials. She also was the author of more than two dozen books, including mystery novels and her memoir, Turned Funny (1988), which was adapted into a play. Her novel Children, My Children (1982) won the Townsend Prize for fiction.

Anne Rivers Siddons (1936–): Siddons is a best-selling author of popular fiction usually set in the South. Although she has written about Maine and the South Carolina Low Country in recent years, two of her best-known novels, Peachtree Road (1989) and Downtown (1994), take place in Atlanta and describe the city’s transformation from a “big small town” into a sprawling metropolis. Two other novels, Homeplace (1987) and Nora, Nora (2000), are set in her hometown of Fairburn.

Lillian Smith (1897–1966): Smith was a white Southern woman who was ahead of her time when it came to civil rights. She was an active foe of racial segregation, a position at the heart of Strange Fruit (1944), a story of interracial love, and Killers of the Dream (1949). Born in Florida, Smith moved with her family in 1915 to Rabun County, where they started Laurel Falls Girls Camp. Smith later ran the camp and cofounded the liberal magazine Pseudopodia with Paula Snelling as a forum open to writers of all races.

Jean Toomer (1894–1967): The son of Georgia parents, Toomer was born in Washington, D.C., and educated in the North, but he found his literary inspiration in the small town of Sparta in Hancock County. While working as a substitute principal, he wrote Cane (1923), a narrative of African-American life that encompasses both the North and rural Georgia. Many black writers, including Alice Walker, have acknowledged Toomer’s influence on their work.

Alice Walker (1946–): Walker is an African-American novelist and poet whose novel The Color Purple (1983) won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. The daughter of sharecroppers in Eatonton, Walker wrote two novels before her masterpiece was published. The Color Purple is a series of letters to God from Celie describing the physical and sexual abuse she endures, her forced marriage, and finally the support she receives from her sister and other women. The book was made into a film by Steven Spielberg in 1985 and was adapted as a musical in 2004.

Bailey White (1950–): White, born in Thomasville, is a former teacher who turned to writing after her National Public Radio essays about eccentric Southerners made her a popular figure. Her essays were collected and published in Mama Makes Up Her Mind (1993) and Sleeping at the Starlite Hotel and Other Adventures on the Way Back Home (1995). In 1998, she published her first novel, Quite a Year for Plums, about a plant pathologist and his romance with a bird artist.

Walter White (1893–1955): Born in Atlanta, White was an author and influential leader of the early civil-rights movement. He founded the Atlanta branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1916 and was the secretary of the NAACP from 1929 to 1955. His novel Fire in the Flint (1924) is the story of the lynching of a black doctor. His second novel, Flight (1926), is an account of the migration of blacks to the North.

Philip Lee Williams (1950–): Born in Madison, Williams is a prolific author whose works include nine novels, two memoirs, a collection of essays, and a children’s book. His first novel, The Heart of a Distant Forest (1986), won the Townsend Prize for fiction. It is the story of a professor who goes to a family cabin to die but finds solace in nature and the friendship of a young boy. Williams has written about crime, passionate love affairs, family mysteries, and the environment. Recently, he turned to history for his novel A Distant Flame (2004), the story of a Confederate sharpshooter in Atlanta as Union forces attack the city.

Calder Willingham (1922–1995): A native of Atlanta, Willingham is noted for his novel End As a Man (1947), based on his experiences as a cadet at the Citadel. Georgia is the setting for Eternal Fire (1963) and Rambling Rose (1972), which was made into a movie starring Laura Dern, Diane Ladd, and Robert Duvall. Willingham was more famous for his screenwriting talents. He cowrote the screenplays for The Graduate and Little Big Man.

Frank Yerby (1916–1991): Yerby, born in Augusta, was famous for historical novels such as The Foxes of Harrow (1946), which were usually published with suggestive covers. He was the first African-American to write a best-selling novel and to sell the book to Hollywood. He wrote 33 novels that sold more than 55 million copies worldwide. His early novels were set in the antebellum South with white protagonists. In his later life, he began to address racial issues in novels such as The Serpent and the Staff (1958) and Speak Now (1969).

The state’s first television station, WSB-TV, began broadcasting in 1948. Today, Georgia has 49 or so stations, including nine public television stations under the umbrella of Georgia Public Broadcasting. You can learn a lot about the state by watching shows about Georgia travel, gardening, politics, business, and the arts on public television. Cable News Network (CNN), the worldwide news operation started by Ted Turner, has its headquarters in Atlanta. The Cartoon Network, Turner Classic Movies, and the Weather Channel are also located in the Metro Atlanta area.

Statewide magazines include the business publication Georgia Trend and Georgia Backroads, which focuses on historical events and travel. Nearly all of the large cities in the state have city magazines. You’ll also find specialty magazines on gardening, dining, fashion, social events, weddings, and home décor and regional magazines such as Points North, which covers the northern Atlanta suburbs.

The Atlanta-Journal Constitution is the largest daily newspaper in the state. Other large papers are located in Columbus, Albany, Augusta, Macon, and Savannah. Creative Loafing, an alternative newspaper offering extensive coverage of music and the arts, is available in Atlanta. And the Atlanta Business Chronicle is considered an excellent source of local business news.

BOOKS AND RESOURCES

Burrison, John A. Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

Georgia Center for the Book. www.georgiacenterforthebook.org.

Georgia Music Hall of Fame. www.georgiamusic.org.

Georgia Writers Hall of Fame. www.libs.edu/gawriters/.

New Georgia Encyclopedia. www.georgiaencyclopedia.org.