3

The Six Challenges of Creating a Category (and How to Overcome Them)

Gustave “Gus” Levy was a college dropout from New Orleans who moved to New York City in 1928 to pursue a career in finance. Levy joined Goldman Sachs in 1933 as a trader on the foreign bond desk for a salary of $27.50 a week. Thirty-six years later, he became senior partner, ushering in a golden age at Goldman of international expansion and an increased tolerance to take on trading risk.

History will remember Levy as one of the most respected executives on Wall Street, but beyond his contributions to Goldman Sachs and the financial industry as a whole, he coined what would become an iconic adage that still echoes through the hallways of the investment banking juggernaut to this day. “Greedy,” Levy would say, “but long-term greedy.”

While the word “greedy” is rather notorious in nature, identified as one of the seven deadly sins and declared “good” by fictional villain Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street, the spirit of Levy’s iconic phrase has powerful application in modern business. Companies that are short-term greedy are almost always outlasted by the long-term greedy. Short-term greed conjures up examples of businesses looking to maximize shareholder value quickly and by any means necessary—even at the expense of employees and customers. Several case studies come to mind, including many Internet businesses in the period between March 11, 2000, to October 9, 2002, now known as the dot-com crash. Perhaps a slightly more principled business that’s short-term greedy today would focus on acquisition as a target exit strategy in order to create quick wealth and notoriety for the founding team.

Companies that are long-term greedy, on the other hand, are not interested in taking any shortcuts on their path to success. They are driven by creating lasting value in the marketplace, doing the right thing by teammates and customers, and realizing the full potential of their vision, regardless of the amount of time that it takes to do so. This is especially novel thinking in technology, where the late-1990s and mid-2010s have been characterized by a surge in M&A activity, larger-than-life corporate valuations, and a frothy venture capital environment—creating widespread religion across Silicon Valley around short-term greed.

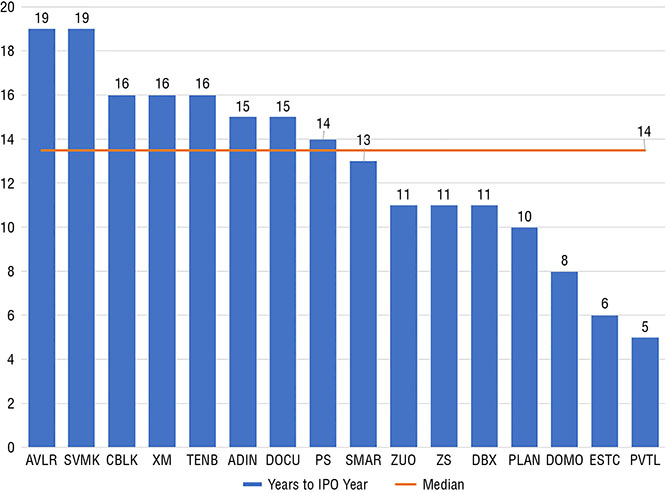

Despite the pervasiveness of that mindset, the truth is that long-term greed has become a prerequisite of success in modern businesses. An analysis of high-growth software IPOs in 2018 by Alex Clayton, Growth Enterprise Investor at Spark Capital, found that it took companies an average of 14 years1 from founding to the public markets (see Figure 3.1). Looking past time frame, public software-as-a-service (SaaS) companies today are “~$200M+ in ARR and growing ~40%, have ~75% GAAP gross margins, are losing money, have a 120% net dollar expansion rate, sell a ~$30K product, have almost 1,000 employees, have raised $300M from investors (and burned through at least $200M of it), and sold over $250M of stock in an IPO at a valuation of ~$2B.” This data certainly paints a different and humbling picture than the get-rich-quick perception of startup fame in Silicon Valley.

Figure 3.1 Years to IPO; Founding Year to IPO Year

However, the truth is that an IPO is merely a financing event. Jason Lemkin, founder of SaaStr—a social community of 500,000+ SaaS founders and executives—has pushed his audience to go even longer than the 14-year IPO journey in pursuit of what he calls building a generational company. Lemkin believes that achieving “unicorn” status and going public is only one milestone on a company’s long journey to becoming generational at $1B+ of ARR. Iconic brands such as Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Workday are already there, while others such as Box, DocuSign, and Zendesk are well on their way.

Embarking on a journey of category creation requires even more long-term greed than the average SaaS IPO. Sure, that greed could manifest itself in time-to-liquidity (don’t count on a quick exit), but in reality, there are several factors that make category creation extremely difficult relative to disrupting existing markets. Let’s explore six challenges of creating a category as well as some key considerations to overcome them. While this list may sound daunting (because it is), going into your journey with eyes wide open will serve you well.

1. Not Everyone Will Get It Right Away

Recall from the first chapter that one of the primary aims of category creation is to position and evangelize a new problem that you’ve observed in the marketplace—often a problem that customers don’t even recognize they have yet. It’s hard enough to position your own company and product, let alone create a cognitive reference for an entire industry. This is the intellectual challenge marketing will wrestle with throughout the journey—balancing category marketing effort of defining (and naming) the problem, with product and demand marketing effort to position the company and product as the solution. At times, it may feel like your category is another product in and of itself.

Over the years at Gainsight, we’ve spent a lot of time (and money) to help the world understand what Customer Success actually is. Many of our programs required two parallel work streams—positioning Customer Success (the category) and then also positioning Gainsight (the company and product). An example would be a quantitative ROI study we conducted early in our journey that required extra scope than perhaps a traditional business. We partnered with a third-party research firm to help us quantify the pain of churn in subscription companies, as well as unrealized expansion revenue and scaling challenges that would justify an investment in the practice of Customer Success.

Among other takeaways, the study proved that companies who adopted Customer Success programs reported a significant boost in sales revenues to the tune of an additional $11M over a three-year period. Now that we had a compelling argument we could evangelize in the marketplace, we wanted to prove the incremental value of using Gainsight to operationalize the Customer Success effort. The study proved that Customer Success teams who used Gainsight were able to reduce churn on average by 5–10x relative to their peer set, while also finding an average of $1M—$5M per year of operational savings by using our technology to scale. You better believe I took out a billboard on the most influential stretch of highway in the world to evangelize that value (seriously, check out Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 Gainsight Highway Billboard Circa 2013

Even if you think billboards are stupid (although I’ll try to convince you otherwise in a later chapter), the meta point is that getting people to believe that what you’ve observed is indeed a problem in the market—by name—is extremely difficult. A signal of your success in time will be recognizing that you’re not the only one screaming your category name into a void, but rather others in the marketplace are starting to refer to it accurately as well. The challenge is that even when you start seeing your category name out there in the wild, the hard work is only getting started.

2. Customers Are Initially Interested in Education, Not Your Product

One of the realities you’ll have to embrace in category creation is the imperative to educate the market through your various marketing channels. No other marketing strategy will place as big an emphasis on education as this one. Once you’ve developed a good content marketing program (which we’ll cover in great detail in Chapters Six and Seven) and are able to capture the market’s attention on the “why” behind your category, those who are listening will look to you for answers on the “how,” which include a logical next set of questions, such as:

- Is CATEGORY X relevant to me?

- How can I convince my CEO that CATEGORY X is important?

- Do I need to build a team to take on a CATEGORY X program?

- What’s a sample job description that I can use to recruit talent?

- How do I prove the value of CATEGORY X on revenue?

- Etc.

This is where the bulk of your content marketing effort will be spent—defining the best practices in the category you’re creating, so that anyone seeking information on the category can quickly and easily find resources online, and more importantly, that the value delivery is attributed to your brand. Nothing is more important in the age of the digitally empowered buyer. Do this right, and a few things will happen: (1) your brand becomes aligned with the category you’re creating in a thought leadership position, and (2) you begin to build an opt-in database of conversions from an audience listening to what you have to say. This strategy should feel somewhat familiar—this is the Inbound Marketing playbook that HubSpot has evangelized. The bet is that if your brand can act as a partner in strategy definition in the market at scale, when companies are ready to evaluate solutions, they’ll engage your team in a sales process, having already received value from your content and perceived you as a trusted partner all along.

The reality is that this is extremely hard to do—especially in the early days when finding time or resources to create high-quality content is difficult. You’ll feel like you’re spending more time creating content about the category than your own products, a feeling you need to become very comfortable with. For a time at Gainsight, we even moved product marketing into the Product organization to focus Marketing’s efforts on category marketing programs. While that tradeoff had its own set of challenges, it was the right thing to do for where we were at the time as a business.

What happens next is arguably the most difficult challenge in category creation—a phenomenon that I’m calling the two funnel effect. A well-executed marketing strategy will create broad awareness of your new category and enroll the masses into your brand and thought leadership by building your marketable database (funnel one). As the market leader in the new category, you’ll run a number of programs against your database that we’ll cover in Part II, driving engagement from your audience as they mature in the new category. Whether through lead scoring, account-based marketing principles, or by some other measure, you’ll identify signals of buying intent from your audience and attempt to engage them in a product- oriented discussion (funnel two). However, for category creators, the chasm between funnel one (interest in the category) and funnel two (interest in the product) can become quite wide. It’s common to find that you’ve won the hearts of your audience by selling them on the problem, but are yet to win their minds by selling them on your product as the solution. We’ll go into greater detail on how to bridge this chasm in Chapter Twelve, but there are several factors that contribute to the distance between the two funnels:

- Buyer is still in strategy definition mode and not yet ready for product

- Buyer needs to hire a key executive or team prior to selecting an enabling product

- Buyer is not empowered to make the purchasing decision

- Buyer doesn’t know how to buy product to solve this problem (never had an opportunity to)

While the two funnel effect will certainly require focus to overcome—as well as tight Sales and Marketing alignment—there is good news here. Building a great funnel one will create a competitive moat around your brand unlike any other tactic, as customers generally prefer to do business with the market leader. Marketing is primarily responsible for building funnel one, as well as closing the divide into funnel two—which takes me to the next challenge.

3. You’ll Need a LOT of Capital (Although There Are Workarounds)

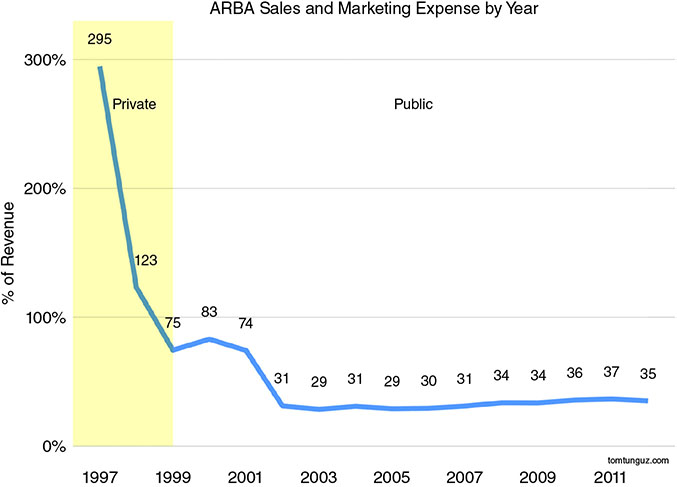

Ariba was founded in 1996 on the idea that the Internet could be leveraged to enable companies to facilitate and improve the procurement process. Their software helped companies buy the things they needed to operate—everything from pens to vehicle fleets. You would be remiss, even back in 1996, to find a less sexy market or buyer than procurement. That was the founding team’s signal, who invested significantly to create the B2B e-Commerce category, fueling Ariba to a $4B IPO in 1999 before being acquired by SAP in 2012 for $4.3B. Fun fact, Ariba was the first B2B Internet IPO in history.

But making procurement sexy did not come cheap. In the years prior to their IPO, Ariba spent $46.4M in sales and marketing efforts before generating more than $200M in revenue.2 As referenced in Figure 3.3 the company over-invested early as a percentage of revenue to create the level of awareness required to spark the flywheel for their category. The company’s annual sales and marketing budget increased by 6x YoY after their IPO to $230M and $298M in 2000 and 2001. Although the bubble burst in 2001, dropping Ariba’s stock price dramatically to its IPO level, the company endured as the largest independent procurement software business and was acquired by SAP at the highest historical multiple of any software company at that point in history.

Figure 3.3 ARBA Sales and Marketing Expense by Year

Although Ariba’s story is quite historic, the lesson applies to all companies who are creating a category. The amount of capital required to create a broad level of awareness around a need that people don’t know they have is non-trivial. It’s no surprise that in new categories the eventual winner is the best-funded, as resources in the early days help category creators (and frankly fast followers as well) distance themselves from the competition. Alex Clayton’s research on high-growth SaaS IPOs in 2018 found a median of $300M of equity capital raised in the private markets before going public.3 Eventually all businesses—whether category creators or disruptors—will have to become more capital efficient and manage sales and marketing expense against industry benchmarks. But especially in the early days, companies need to fight risk aversion and invest in marketing programs that will build the foundation for new industry. However there’s a complicating factor for category creators that will challenge thinking on how to deploy capital, even in cavalier ways.

A Note for Bootstrapped Startups

It’s important for me to recognize at this point that there are many early stage companies that may resonate with what I’ve written so far on category creation, but have felt a sense of defeat after reading the last section on capital. Silicon Valley, where I work, is in almost every case the exception and not the norm. Access to angel and early stage venture capital, top-tier talent, and innovation-centric educational institutions are only some of the characteristics that give Silicon Valley an unfair advantage on the rest of the world. You can probably go down the list and argue a similar position for New York City, Seattle, Austin, and other emerging secondary markets in the United States.

The reality is that not every company has equal access to capital; however we all possess equal ambition to create big visions for our businesses. If you are bootstrapping your company, or are in the early days of putting your concept together, I want you to know that this book is also written for you. As we dive into the “Seven Principles to Create (and Dominate) a Category” in Part II, we will walk through a detailed playbook on how to execute a category creation strategy. Some of the ideas will seem capital intensive (e.g., create an industry conference of record for your category), but most will feel achievable with the right balance of priority and scale. I will make sure to provide examples and case studies of capital efficient ways of executing the same playbook as we delve into each topic. Following these principles can put your company in a position to generate enough sustainable growth to either self-fund your future or take in outside funding to scale later down the road.

The truth is wherever you are geographically, and with little or no institutional funding, you can still create a category and build a generational company along the way. Don’t believe me? In 2002, a college student named Ryan Smith decided to build an online research company with his father from his parents’ basement in Provo, Utah. They targeted the academia market, arguably one of the toughest verticals, with little budget and extremely long sales cycles. Ten years later in 2012, they took their first round of funding after Accel and Sequoia had been knocking down their door for three years. Days before their IPO in November 2018, Ryan Smith, his father, and the rest of the Qualtrics team were acquired by SAP for $8B in cash. When asked about that decision to take institutional investment back in 2012, Ryan had this to say: “One plus one has to equal five. If one plus one doesn’t equal five, this deal doesn’t work. It has to be so compelling to achieve our objectives that we’re all in. We got Sequoia and Accel and that’s exactly what happened.”4

Ryan Smith and Qualtrics are creating the Experience Management (XM) category, and for the most part, have been extremely successful while bootstrapping the business from over 800 miles away from Palo Alto. It may have taken them 16 years—which relative to the 14-year median of 2018’s IPO class is somewhat within range—but they’ve built a generational business that flies in the face of Silicon Valley consensus.

4. Short-Term Planning Is Extremely Hard

Marketing attribution and sales forecasting are hard enough when your business can identify and pursue a market using BANT (Budget, Authority, Needs, and Timeline) as a qualification framework. However, when you’re creating a category, you can pretty much count on throwing BANT out the window—or at least BAT. Here’s why:

- Budget. For new categories, it’s common that your buyer has never procured software (or other purpose-built products) to solve this problem before and will need to find the dollars from elsewhere in the budget.

- Authority. In many cases, your buyer is either not empowered to make purchasing decisions, or otherwise needs to build a business case up the org chart in order to do a deal.

- Timeline. Buying a product is only one part of category creation as prospects are still wrapping their heads around the problem, defining their strategy, and building their team to take the charter.

Qualifying need is critical, but exponentially more difficult in new categories due to the two funnel effect I introduced earlier. The cost to acquire a conversion in funnel one is high enough, never mind how to bridge that conversion into funnel two, and eventually as a paid customer of your product. So without a proven attribution or sales qualification framework to benchmark against, how do you justify investments in category marketing?

5. Executives and Investors Need to Buy In or You Will Fail

Without any question, category creation starts at the top—you need both an executive team and set of investors who are patient, have bought into the mission, and are long-term greedy. The challenges we’re establishing in this chapter are non-trivial, and require decision making and strategic planning at the CEO and board level—without it, the category marketing programs I’ll advocate running throughout the book will not be funded, or almost certainly abandoned if without quick results. The threat of confirmation bias in management is especially applicable as the teams you’ll build and investors you engage would likely have spent more time operating and funding market disruptors rather than market creators. Sales quarters can be bumpy, CAC ratios out of whack in the early innings, but building something amazing requires patience, courage, and conviction. This also shows up in the culture you build within your sales organization—prototypical AEs who are used to “set ’em up and knock ’em down” sales processes will either need to be converted or weeded out of the organization—otherwise they will happily leave on their own. I can’t understate how important culture is to building a new category, a topic we’ll go into in Chapters Five and Thirteen.

If you need to convince your leadership or investors to take the leap and create a category, you may be playing from behind already. The impact to enterprise valuation and business growth that I summarized in Chapter One alone should set the stage on your behalf, but identifying the signals within your own company and building your business case accordingly should push them over the edge. Remember that category and brand marketing fundamentally drive growth—arguably in a much more sustainable way than traditional methods. Ultimately, the ability to attribute every marketing activity to a funnel metric is critical to proving the ROI of category marketing efforts and getting budget approval to run more plays.

We’ll go into the specifics in Chapter Twelve, but down-funnel metrics such as sales forecasting get more predictive in time as your category matures—developing a common language and point of view as a revenue team is important to keep executives aligned on the mission, and the CFO supportive of adding fuel in the form of budget dollars to the fire that you’re sparking.

6. Understanding the Competition Is Confusing

While one of the signals of category creation is no identified incumbent in the market, there are often small companies that either compete directly or compete at the fringes that will eventually adopt your category positioning once traction is made. However, in new markets, it’s really not about the competition, but rather all about the market itself. The true competition for category creators, especially in the early days, is creating enough inertia to will the market into existence—and being ignorant enough to not be distracted by what the competition is doing.

While it may seem counterintuitive, competition is actually a critical component to the success of new markets—otherwise inviting the criticism of whether or not it’s a real category at all. How you choose to engage your competition, however, is a calculated decision that each company should make itself. Within Gainsight’s core business, we made the decision to respectfully “ignore” the competitors in our young category and focus primarily on building the market while positioning our brand as the thought leader. We chose to take up as much of the oxygen in Customer Success as we could, recognizing that there were other vendors in our market who were contributing to the conversation as well.

Other companies stand by a different approach—take Mark Organ, CEO and founder of Influitive and creator of the Advocate Marketing category (Mark was also the founder of Eloqua, the creators of the Marketing Automation category). Mark believes that for category creators, co-opetition trumps competition, as the primary responsibility of the leader is to enlarge the collective total addressable market (TAM). At Influitive, Mark and team spent over $1M to put their competitors on stage as speakers and sponsors of their industry event for Advocate Marketing called Advocamp. Mark believes that losing deals to the competition is a better alternative than losing to status quo, as it means demand for the category is growing.

In either approach, the way you choose to rationalize the competitive landscape in new categories will be fundamentally different from taking a challenger position against an incumbent player in an existing market. You may not necessarily see each other in every deal, but you are in a sense competing for thought leadership. Customers and prospects are building affinity with the different vendors in the marketplace through content and evangelism efforts, whether they’re paying customers yet or not.

At this point, if you are a startup founder or marketer interested in creating a category from the ground up, I want to give you permission to skip ahead to Chapter Five, where we’ll dive into the playbook with 10 principles to create (and dominate) a category—proven strategies as shared by some of the leading category creators in the modern economy.

I want to talk directly to the enterprise marketers and executives, who may be excited at the prospect of creating a category, but are grounded in the reality of working at a company currently operating in a crowded market. The truth is that you have an opportunity to either (a) reposition your established brand around a new market category by building, partnering, or buying your way into a new (or emerging) product category or (b) leverage a certain set of unfair advantages that you possess over startup competitors to re-imagine your brand in a B2H context. Those are the options we’ll explore, and the playbook we’ll dive into in Part II will be just as valid to you and your teams. But before we get to that, there are a few nuances for established brands that are worth disclosing.

Notes

- 1 Alex Clayton, “2018 Review: High-growth SaaS IPOs,” Medium, December 2018, https://medium.com/@alexfclayton/2018-review-high-growth-saas-ipos -5b82a93295c

- 2 Tomasz Tunguz, “From $800k to $274M in 4 Years—The Story of Ariba,” May 2015, https://tomtunguz.com/ariba-history/

- 3 Alex Clayton, “2018 Review: High-Growth SaaS IPOs,” Medium, December 2018, https://medium.com/@alexfclayton/2018-review-high-growth-saas-ipos -5b82a93295c

- 4 Derek Andersen, “The Story Behind Qualtrics, the Next Great Enterprise Company.” TechCrunch, March 2013, https://techcrunch.com/2013/03/02/the -story-behind-qualtrics-the-next-great-enterprise-company/