4

Special Considerations for Established Companies in Commoditized Markets

The year is 2012 and the team at Amazon is busy asserting their dominance as the web’s largest retailer by invading any tangential territory even slightly related to their business. The company had just released new e-book readers and tablet hardware, acquired a book publishing company, and even opened up a social gaming studio. While these investments may seem a few steps removed from their core retail business, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is intentionally and masterfully executing his plan of building a content ecosystem of apps, books, music, and movies as a competitive moat around the Amazon brand.

Within the core business, the historic success of Amazon had ushered in for the market at large what some commentators have referred to as the “retail apocalypse.” The Amazon effect was felt across both Main Street and Wall Street, as mom-and-pop stores were forced to embrace the rising e-commerce trend, while major big-box stores were at the risk of going out of business by losing to the convenience that Amazon introduced to the market. From 2015 to 2019, over 68 major retailers filed for bankruptcy, according to CB Insights,1 citing issues such as mounting losses and drops in sales. One of the companies caught in Amazon’s cross-hairs was Best Buy, who seemed to be one of the last electronics retailers standing after the collapse of Circuit City, CompUSA, RadioShack, and others. Best Buy was bleeding money as customers would come into the store to test products they were interested in only to buy them later online on Amazon at a cheaper price.

Seven years later, not only is Best Buy still alive, but the company is thriving—reporting strong results in fiscal 2019, beating guidance last quarter by generating $14.8B of revenue, and offering a solid outlook for fiscal 2020. It wasn’t just Best Buy, but other retailers such as Costco and Kohls redefined their businesses in the shadows of the retail apocalypse and as a result are winning in the market. How did they do it? Also, what do their stories tell us about the market conditions that put them on their heels in the first place?

The Commoditization of Industry

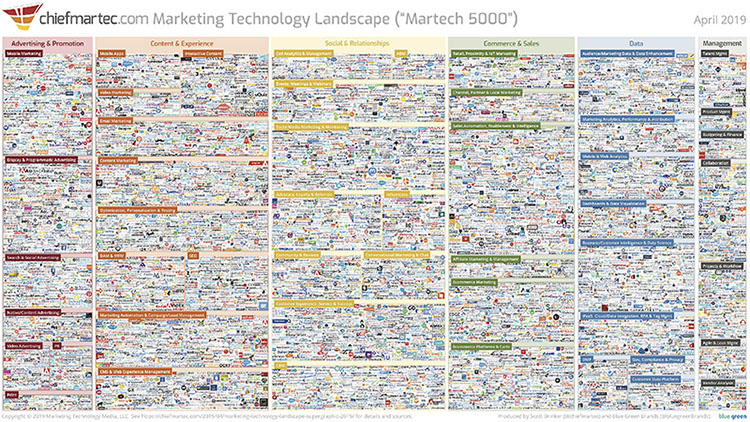

The retail apocalypse has proven that it’s not just products, but entire industries that can become commoditized. Consider the Cloud Computing category that we referenced in Chapter Two—born out of a noble “end of software” movement that today has become the primary method for developing and distributing business and consumer applications. There are distinct similarities between the commoditization of the retail and software industries, as well as other categories such as transportation and energy storage—the arrival of breakthrough innovation and new business models that are willed into existence by an eventual category winner. Let’s take a look at cloud computing technology, as an example, which has introduced innovation that has lowered the barrier to develop and ship applications at scale. The cloud has also reduced the barriers for driving customer acquisition by making it easier for customers to try and buy with models such as freemium, free trial, or pay-per-use. Today any entrepreneur with a great concept can build a technology product without a computer science degree and can become an online retailer without the need for brick and mortar. This innovation has resulted in an explosion of applications available to businesses and consumers online, pushing the software industry closer toward commoditization. If you don’t believe me, Figure 4.1 illustrates the marketing technology landscape in 2019 of over 7,040 solutions as compiled by Scott Brinker and the team at the Chief Marketing Technologist blog.2

Figure 4.1 Marketing Technology Landscape Supergraphic (2019) by ChiefMarTec

The impact of commoditization is typically a good thing for customers—as they now have more options than ever before when making purchasing decisions. In Chapter One, I referenced the file storage and sharing industry, which (according to G2) is a market made up of 285 vendors at the time of publishing. What’s good for customers, however, is not always good for vendors operating in a crowded market—referencing the previous example, today’s entrepreneurs may want to reconsider launching a new file sharing service anytime soon. Companies can choose to compete on price, but ultimately will need a more sustainable and future-proof business strategy to win market share in a crowded industry.

That’s the essence of category creation, which is in effect, a response to the commoditization of industry—why join the conversation when you can just create your own? Early stage founders and marketers have the luxury of agility with positioning while being privately held, but established companies are established for a reason. They have a developed brand perception in the marketplace, are generating revenue with their core products, and in some cases have to answer to Wall Street for any material changes to corporate strategy. Risk aversion is indeed a real thing for enterprise brands, and the idea of creating a new market category around the core offering may seem difficult or even impossible. So what can companies in this position do to breakthrough the noise?

Option 1: Launch into a New Product Category

Established companies are typically either category incumbents (think Oracle in database technology) or fast followers who have chased and successfully challenged a market leader (think Tesla in electric cars). In either case, established companies possess a unique opportunity to uplevel their existing market category by launching new product offerings into entirely new product categories that roll into their overarching brand promise. Product teams tasked with figuring this out will typically conduct a build, partner, buy analysis: either organically develop the new product line in house, partner with a market leader, or acquire them outright. Choosing to build comes with a unique set of challenges, including time to market and taking resources off of the core businesses. Many companies will consider partnership as a valid option to run an experiment in the new product category, the most productive of which may sometimes result in an M&A outcome. Ultimately, buying a market-leading brand and product will be the fastest path to the top position in an early market. Whichever path is chosen, launching into a new product category can often put an established company in a 1+1=3 scenario where the acquired product elevates the legacy category in new and exciting ways.

There are many examples where this has been the case—Salesforce acquired Demandware in 2016 and entered the e-commerce industry, strengthening their B2C business and expanding their customer relationship management (CRM) suite to include consumer use cases. Adobe acquired Marketo in 2018 to expand their Experience Cloud positioning to include a B2B audience. While M&A certainly isn’t the only way to launch into a new product category, it’s a great example of the unfair advantage that established brands possess over the upstart competition. Understanding how to leverage those unfair advantages, while also being aware of organizational blind spots, may be the difference between moving up the ranks and truly becoming a category leader.

Option 2: Leverage Your Unfair Advantage to Become a Category Leader

So how exactly has Best Buy managed to survive the Amazon effect and retail apocalypse? When former Best Buy CEO Hubert Joly took the position in 2012, he began to implement a series of programs that would leverage the company’s unfair advantage over the competition. First, he invested in his employees, who had felt neglected under previous leadership—fixing broken internal systems, reinstating an employee discount program, and investing deeply in regular employee training. As the late Herb Kelleher, co-founder of Southwest Airlines, once said, “Employees come first. If you treat them well, then they treat the customers well, and that means your customers come back and your shareholders are happy.” The adage proved true for Best Buy, who according to Glassdoor, currently boasts a 78% “recommend to a friend” rating and a 92% “approval of CEO” rating as of March 2019.

Joly understood that Best Buy’s brick-and-mortar footprint was something that Amazon did not have; however, a new phenomenon called “showrooming” began to take shape in which customers would walk into a big-box store to check out a product in person before going online to buy it (cheaper) on Amazon. He viewed showrooming as an opportunity to gain advantage, given the customer was in store, and as he put it, was “ours to lose.”3 Joly instituted a price matching program and formed strategic partnerships with major electronics manufacturers such as Apple and Samsung to rent square footage within Best Buy’s store and feature their products within a branded space. With that strategy, Amazon lost their competitive high ground on pricing, and since the customer was in store, the convenience of walking out of Best Buy with the product in-hand made more sense than waiting for an Amazon delivery.

Finally, Joly appreciated that Best Buy was able to do something that Amazon (at least for now) could not do—build relationships with customers in person. He decided to double down on services such as the Geek Squad technical support and the new In-Home Advisor programs—solutions that added value beyond the commoditized products available on the shelves, building trust and creating brand equity with the customer. While services today represent only a single-digit percentage of Best Buy’s overall revenue, it’s a high-margin business that’s key to the company’s future growth.

Best Buy will need to continue innovating to keep up with Amazon—and as a consumer, it’s hard to tell whether they’re on the right side of history. But Joly doesn’t believe it has to be a zero-sum game, saying, “You won’t get me to say a bad word about Amazon. There is a lot of room for both of us.”4

In Best Buy’s case, they were able to leverage these unfair advantages—their engaged workforce, physical footprint, customer relationships, and value-added services—to break away from the noise in their industry and build a new type of retail experience with customers at the center. There are common unfair advantages that established brands possess over the competition that can be extremely helpful levers to reposition away from a crowded marketplace. While established brands are often given a bad rep (slow and inefficient) relative to nimble and innovative startups, these same weaknesses can be turned into strengths in order to accelerate market dominance at a pace no startup could ever compete with. Here are three common unfair advantages to consider leveraging.

1. Existing Customer Base

The very definition of established brand connotes an active install base of customers who are already using your products or services. The relationships that have been developed with customers over the years will serve as a strategic advantage over competition still focused on acquiring an initial set of early adopters. Customers can serve as invaluable sources of feedback on positioning through programs such as customer advisory boards or brand advocates willing to evangelize in the marketplace. If you’re considering launching a new product offering to the same buyer as your core business, your customers are the highest leveraged demand gen expense as you aim to cross-sell the new product offering. If the new product offering is targeting a completely different buyer, customers are (again) a high-leverage referral source for introductions to the new buyer at the customer account.

In either case, established brands can leverage the laws of price elasticity to launch new offerings into their installed base in clever ways. Imagine a promotion to existing customers where they can access the new product offering for free (or cheap) for one year, so long as they agree to fully evaluate your solution as a rip-and-replace of what they’re currently using at the time of renewal. In this example, the barrier to entry for customers is pretty low (no cost), demonstrates value (product capabilities), and the costs to acquire a customer are much lower than programs at the top of the funnel. Perhaps customers who participate will also agree to serve as early advocates of the new product line—providing a quote, rights to use their logo publicly, or even participating in marketing programs such as webinars and live events. Developing the competitive offer is easy (meaning any company can technically do that), but the hard thing is developing an engaged customer base to launch into—an unfair advantage that only established companies possess.

2. Established Brand Equity

While startup companies find themselves in a position where they need to build their brands from the ground up, established companies have already done so. As an example, when you see the Ford logo, you have a cognitive reference embedded in your mind of a generational American company that has transformed the transportation industry. As Ford builds, partners, or buys their way into bike share programs, commuter shuttle services, or even electric scooters, the company can lean on the brand equity that it has developed in the marketplace as the transportation and mobility leader to extend that very leadership into emerging business lines. A startup in the electric scooter industry has to work exponentially harder to win the trust of consumers.

It’s also critically important for established companies to be continually evolving while never compromising their purpose, promise, and values. Warren Buffet’s adage that “it takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it” is especially relevant in this context. However, marketing itself is in a constant state of renewal, and established brands need to leverage emerging communications mediums to stay relevant to their evolving customer base. You can think of several examples in the consumer world of companies who have been able to leverage their tenured brand equity while also keeping up with modern marketing practices—Coca-Cola, Disney, and Nike, just to name a few. The chapters that follow will offer exciting ideas to strengthen established brand equity in engaging and relevant ways.

3. Budget and Go-to-Market (GTM) Resources

Recall that one of the six challenges to creating a category that I referenced in the last chapter was having enough capital deployed to create a broad level of awareness around unmet need in the marketplace. This is especially difficult for bootstrapped startups, but not always the case for established companies making a conscious effort to invest. There are several budget levers that give advantage to established companies over startup competition:

- Program Budget. Marketers can spend money to buy their way into new markets through paid media, creating organic content optimized for long-tail search, exhibiting at industry tradeshows, and so on. The less resources are constrained, the fewer tradeoffs have to be made on which programs marketing can invest in to grow awareness in the early innings.

- Headcount. Especially in early markets, established brands have an opportunity to scale hiring sales reps, content marketers, and other GTM functions in order to overwhelm the capacity of startups.

- M&A. As I mentioned earlier, a thoughtful business case on new market entry will typically include a build, partner, or buy analysis—where companies are faced with a decision on whether to pursue organic product development, strategic partnerships, or M&A in order to launch into new categories. Acquiring a company may prove to be the fastest path to entering a new market in a leadership position.

Budget and resources are critical advantages for established brands that can enable faster path to market leadership; however, accessing the dollars alone will not create the advantage. One edge that startups gain from the absence of resources is the requirement to be conservative with spend, test assumptions before making big bets, and ultimately prove the ROI of each dollar spent in sales and marketing. The playbook that I’ll share in the chapters that follow will give you and your teams the tools they need to execute on either of the above two approaches with more resources than our startup friends, but with the same degree of innovation and creativity.

Notes

- 1 “Here’s a List of 68 Bankruptcies in the Retail Apocalypse and Why They Failed.” CB Insights, March 2019, https://www.cbinsights.com/research/retail -apocalypse-timeline-infographic/

- 2 Scott Brinker, “Marketing Technology Landscape Supergraphic (2019): Martech 5000 (actually 7,040).” ChiefMarTec, April 2019, https://chiefmartec .com/2019/04/marketing-technology-landscape-supergraphic-2019/

- 3 Kevin Roose, “Best Buy’s Secrets for Thriving in the Amazon Age,” New York Times, September 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/18/business/best -buy-amazon.html

- 4 Justin Bariso, “Amazon Almost Killed Best Buy. Then, Best Buy Did Something Completely Brilliant.” Inc., September 2017, https://www.inc.com/justin-bariso /amazon-almost-killed-best-buy-then-best-buy-did-something-completely -brilliant.html