As artists we must go out of our way to create visual recession in the most convincing way possible by manipulating edges and forms. Use the following methods to convey a sense of depth in your landscape paintings.

By placing one item in front of another, we send a message to the viewer that something is in front and something is behind. The fountain placed in front of the building helps convey a sense of depth. Take into account that the more we overlap something, we remove importance from the object when it is being partially blocked. Careful consideration is to be given how much you want something to overlap a center of interest, or you may minimize it.

You can see miles of depth in this painting. The closer cliffs take on a warm violet, shifting to blue-violet in the mid ground, and then blue in the furthest plane.

Unless it is a foggy day, the obvious effect of atmospheric perspective is unnoticeable for planes that are just hundreds of feet away. In a normal day, you will start to see things getting bluer and lighter at about one mile away from you. You can really exploit this to create the illusion of depth.

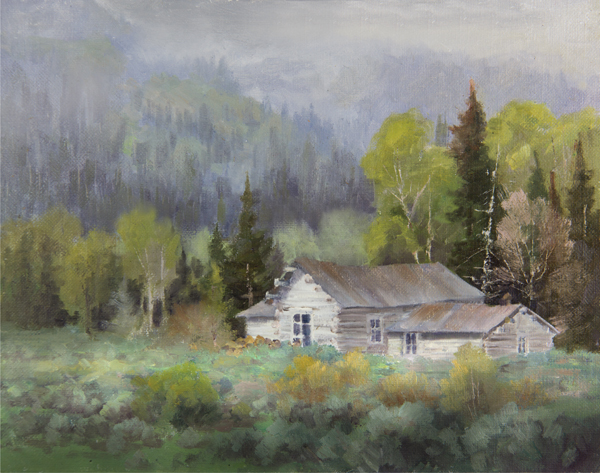

Nothing can beat this wonderful and handy tool to convey a sense of depth. It is great for separating planes. Otherwise they would all be the same value. In the forest area, it would be very difficult to convey the sense of recession without the fog. Solely overlapping the trees will not deliver a good enough sense of depth. Objects will always get lighter when they are yards apart and more simplified the deeper they recede into the fog. The fog also helps to keep the house from appearing as though it is sitting on top of the boat.

If those fishing shacks were to be painted as they appear in the photo, the end result would be a sense of crowding them together. Logically we can measure the space in between each building, but visually we cannot. Because the photo flattened the scene, some buildings in this scene appear to be on top of each other. When there is nothing between the buildings, the sense of field depth is gone. This is why grass and fog were added between the houses.

When air molecules are thick because of high humidity, the atmosphere will absorb the warm rays of the late evening sunlight and give off a warm glowing light. This creates a mood which is very pleasant in paintings. Viewers tend to be drawn to paintings with moods.

Ground fog can give the viewer an out-of-the-ordinary view. Depicting ground fog in this painting is what got me Mexico’s top award in watercolor media. This was done on a watercolor sheet called Elephant Ear, which measured 60" × 44" (152cm × 112cm). I had to lie on the floor to do certain areas.

A painting can be too cool or too warm. The trick is to find the correct balance between the two and to use colors of both temperatures to compensate each other. Autumn scenes can be disturbing because of all the warm colors that would look too garish. Fog can soothe this overwhelming color temperature. Also by not depicting sunlight, the oranges end up being toned down.

Contrasting blurry and sharp edges against each other is very effective for showing depth. Anything solid and static does not have diffused edges in the real world. Only things that contain water, such as foam or clouds will appear blurred. You will need to rely on blurring edges even though you cannot see them on solid objects. This becomes another tool to give the illusion that things are far away.

This house portrait shows overlapping from the lamp posts and the birch tree. The biggest asset for recession in this watercolor is the wet-on-wet technique in the background. When contrasted against the sharp edges of the house, it makes the foliage appear to recede several planes. Soft bleeding edges should always be present in watercolors. Watercolor allows for wonderful diffused edges, but lacks the ability to add thick impasto as texture.

Backgrounds will appear to be in a distant plane when the edges are diffused. In real life, a background is not soft. In this detail view, the house appears to come forward.

The planes behind man made structures should be out of focus when it comes to foliage and hills. An exception to this would be rocky mountains. The angular structure which gives them character would become weakened.

The more planes a painting has, the more depth that is perceived. You can have sub planes within the three main planes (background, mid ground and foreground). Always create a minimum of three planes in your composition—more if possible. In this painting, the idea was to make viewers feel like they could walk through the forest by creating layers of foliage as the forest gradually gets deeper. This painting gives a very convincing sense of depth in the background, which is nonexistent in the real life scene because the evergreens line up like birds on a wire and block anything behind them.

The principles of atmospheric perspective apply as long as all planes get the equal degree of light. All bets are off when a rain cloud casts a shadow over one plane and the sun is allowed to shed light on another plane. When this is the case, a background that is in shadow will not be lighter than a closer plane, such as the middle ground or foreground if the sun is peeking through the clouds only in those areas. When an overall plane is in a different value than another, the separation of these planes will be quite obvious as seen in this painting. Viewers will feel more invited when you darken a foreground plane and lighten the middle ground or background plane.

In the first image, the closest plane of evergreens is lighter than the ones behind them. The value pattern was reversed in the second picture. The overall value of the planes can be interchanged and the sense of depth will still apply. If both planes of evergreens forests are in the same value, then our sense of field depth will be compromised and we would only rely on atmospheric perspective and size perspective to indicate depth.

Heavy impasto (thick paint) will convey that foreground objects are closer. You can reduce the thickness of paint for shapes in the mid ground. In the background avoid heavy paint—use just enough to show the brushstrokes. Oil paint and acrylics have this advantage over other mediums.

The surface was prepared with Liquitex super heavy gesso to build the texture before adding the colored pigment. The red-orange bush in the foreground was done with a drybrush technique and very thick paint. By applying a light touch, like tickling, the pigment peeled of the brush leaving the broken paint. Watercolor paper also works well for the drybrush technique. Hot-pressed (rough) paper leaves more gaps in between than cold-pressed (smooth) paper does.

Negative painting creates visual orifices. Think of it as engraving an insignia in a ring. We can apply this same principle with foliage. Negative painting was used in this winter scene to bring out the positive shapes of the tree branches. This is a great way to create visual indentations for depth as well as establish the intent of design. This also forces you to work from your artistic brain, because as a child, you never did this so there is no preconceived memory of the process. No childhood habits will interfere. If there are no visual orifices in foliage, it will appear like a flat wall. There would be no place where a bird can protect itself from pouring rain and strong wind. The branches of the frosted trees were brought out by painting the dark spots into the lighter values. This reverse painting method brings out abstract negative shapes as well.

It is very common when foliage is about the length of a football field away from you that the bushes and trees seem to line up in a straight line like a wall. This will result in a visual pace that is too fast from side to side, and a rectangle will form from the horizontal grass planes. The sense of some trees being in front of other trees vanishes. Equate this to a chess game that has not begun. The trees and bushes in the picture line up like the chess pieces.

Think of a box. If we only show one side, it will look like a square, but as soon as we turn it we have a cube as long as both sides have different values. This concept applies to still lifes, portraits, wildlife and especially to buildings.

We all have the habit of writing from left to right in the Western world. We place words adjacent to each other. When we paint, we tend to repeat this habit with our landscape symbols like placing houses next to each other on a street. To break this habit, consciously position landscape objects unevenly in front of each other so there is recession from front to back. This is much more important than thinking side to side. Visualize a chess board and pretend you are moving trees, bushes, rocks, etc., like chess pieces coming forward. In the painting the large left tree was brought forward three squares. Some bushes were placed unevenly in front of the right tree, so the pawns were moved one and two squares.

The straight line where the foliage meets the grass in the photo, the rectangular portion of the grass, and the absence of field depth have all been corrected. Checkmate! I beat the photo!

This approach is used by animation illustrators and it is very effective. In a gradient plane, a value can become gradually darker or lighter in the distance or a color temperature can become warmer or cooler as it recedes. Gradient planes give a very good impression that horizontal planes are receding. Vertical planes seem to have more height and length when gradiated.

This foreground in the first picture is very flat. Since there is no river or stream to indicate a visual path, we can cast a shadow over the foreground to draw the viewer in. There is a convincing impression of depth in the second painting now. The value gradually gets lighter as it goes deeper in, hence the name, gradient plane.

This field study was done during an overcast day. I saw the same value of blue-gray in the entire body of water. Had I not lightened areas of that water, the painting would lack a convincing sense of depth. Lakes, seascapes and rivers give us great opportunities for gradient planes because they reflect the sky that can have so many variances of values.

This alternative view is showing a gradient plane, light to dark instead of dark to light like the picture above. The recession is still conveyed. It is just another version. This spot-lighting technique is an effective way to control where you want light. The rocks at the very bottom are darker than the ones further out into the distance. This also becomes a gradient plane. The grass in the middle ground gets darker towards the left edge as well. The ground becomes bluer and lighter near the far mountain range showing atmospheric perspective.

Skies can be boring and flat if the same value appears all the way across. In this painting, the right side is lighter indicating that the sun is just out of the picture. This is a great excuse to show a gradient plane in the sky for more interest.

The warm areas near the bottom of the mountains are reflected light off the lake, which would act like a mirror casting bounced sunlight near the bottom. This also is labeled a gradient plane. Some evergreens have a warm glow and are also gradient. This adds interest to that section. Again the transition from light to dark, warm to cool will achieve that.

This scene has several subtle gradient planes. The wall with the arch is lighter and warmer at the bottom. The gray building is warmer near the bottom. The yellow arch is showing a lighter value right next to the wall. All this can be justified as reflective light bouncing off the adjacent planes. The cobble stone road is darker in the immediate foreground and gradually gets lighter as it recedes.

Reflective light will bounce off horizontal planes. In the stone building, the wall appears to recede much better than if it was a flat value all the way across. In real life, you probably would not see the wall progressively getting lighter. The roof starts with a cool blue and gradually fades into pink. This characterizes the house as being part of an animated movie. Under the eaves it is darker where the two sections of the roof form a “V”. The bottom of the chimney is lighter than the top. Take into account that indicating gradient planes is an artificial technique, but very effective in paintings. Make sure the lightest value in the shadow side of a plane is darker than any area in the sunlit façade. The 3⁄4 position of the building allows for these effects.

Depending on how the sun is positioned, many trees in photos do not show 3D volume, just height and width. If painted as they appear in real life or photos, they will have a flat two-dimensional look. These simple drawings show simplified versions of landscape shapes showing volume because of the shadow side. As you are painting, think of trees as spheres, tree trunks as cylinders, rocks and mountains as cubes, and evergreen trees as cones. Plan your light to come from the side so that the opposite side ends up with a darker side. Make sure that when you include animals, vehicles, people and buildings, you place them at a 3⁄4 position and have two different sides in two different values. All these factors accentuate to nullify the flatness.

In real life, the eye will see equal color intensity in a field of grass in the foreground compared to hundreds of yards away. Unless it is a muggy day, atmospheric perspective takes effect and becomes noticeable, not hundreds of yards away, but almost a mile away. We know the brain has its own mechanism to sense depth. Painted exactly as it appears, the grass will not recede enough in a painting. To achieve recession, reduce color intensity at the end of the field in case the colors of trees and grass are the same up front and in the distance. The color intensity in the bush was pumped up a bit to bring it closer compared to the one behind it. The furthest grass has been grayed down by adding Violet to the same mixture used in the foreground.

When areas of equal color and value are placed somewhere else and are disjointed, the top portion seems to hover above instead of receding.

In the first version of the painting, the snow patch in the distant mountain is the same value and color as the waterfall. It seems like two white poker chips on top of each other in the same stack separated by other colors.

In the corrected version, the snow was darkened. Now it seems that area recedes at least one mile. There is a better sense of field depth.