The great seasonal festivals of the year have their origins in the rhythm of the earth and the primitive religion of people whose natural instincts were for self-preservation and racial survival. Before science explained nature, mysteriously the seasons brought food for life’s survival. But equally difficult to understand was why one year there was plenty and the next year not enough. So they kindled a symbolic bonfire in the hope that it would please the life-giving sun. They offered sacrifices of thanksgiving, and performed many symbolic acts which they hoped would encourage nature to treat them kindly. When it did, they believed that their actions had been correct. Superstition, sacrifice, myth, magic and folklore, relating to nature, was their religion.

Though they were simple nature-worshippers, indulging in what are now regarded as naive practices, their motivation was entirely logical, and their emotions about nature extremely powerful. They were not just happy when winter ended and spring began, or sad when summer faded into autumn, they worshipped this progress of the yearly cycle. It was a cause of adoration and reverence, that life should be followed by death, followed by rebirth. The yearly cycle of life, death and resurrection gave them their faith. Each group of peoples took a consensus on what seemed to be the most effective rites and ceremonies which then became their distinctive beliefs and dogmas.

Living on the islands which now make up the UK, there was an amalgam of racial strains of primitive peoples in different permutations, and in different proportions, which eventually created four distinct nations within a comparatively small area. In Scotland, the predominant racial strain was Celtic. There was also a strong mixture of Scandinavian blood from the Norse colonies in Caithness, Orkney and Shetland plus a few ‘pirate nests’ in the Hebrides and along the coasts. Though there were other racial strains (Northern English, Flemish and Norman) there were no wholesale conquests in this primitive period of Scottish history, and so the great festivals of the ancient Celtic and Norse people in Scotland became firmly established and nationally distinct.

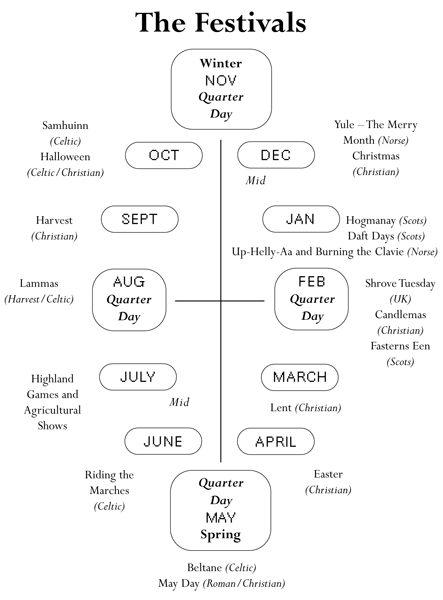

While the Norse sea reivers followed the movements of the sun and the moon, celebrating their festivals according to the solstices and equinoxes, the romantic, mystical, poetical Celts divided their year according to the movement of flocks from lowland pasture to highland pasture and vice versa. In the Celtic calendar, Beltane (1 May) was the beginning of summer while Samhuinn (31 October) was the beginning of winter; 1 November was the end of the old year and the beginning of the new. The Celtic New Year began at sunset on 31 October.

It’s a variation in the division of the year which continues to this day, with the Scottish Quarter days occurring in February, May, August and November while in England they are in March, June, September and December.

Among the ancient Celts, the most influential nature worshippers were the Druids, though they were by no means the only cult. Christian missionaries discovered several others, as well as many popular superstitions and magical practices which pre-dated the Druids. But compared with the early beliefs of other primitive peoples, Druidism was a sophisticated, civilizing force, practising divine worship and involving priests who were regarded as philosophers and theologians. They had a powerful esoteric attraction and practised secret priestly rites. They took on the management of order in the community, educating children as well as taking responsibility for settling disputes and deciding rewards and penalties. Unlike non-Celtic Europe, which had polytheistic systems, the mystical nature-worship of the Celtic Druids proved to be much more compatible with the new Christian faith which arrived in Scotland with St Ninian at the Isle of Whithorn (fourth century) and St Columba on Iona (sixth century).

In the first century, the Christian church celebrated only Sundays, Easter and Pentecost. In the second century, Lent was initiated and in the fourth century there was the institution of Saints’ days. Though the Nativity of Christ is mentioned in the second century, it was not until the sixth century that it became a universal celebration.

During the early days of Christian mission, the priests had great difficulty converting the people from sun worshipping to worshipping a God of love and forgiveness who had nothing to do with the practical needs of day-to-day self-preservation. Of course the church failed, and the people continued to carry on with the old familiar rites and ceremonies. Which is hardly surprising, considering that these customs had been regarded as vital to their survival since the beginnings of existence. The solution for the Christian church was to accept defeat. The times of the nature festivals would be preserved, some of the less barbaric rites and ceremonies of the nature-worshippers could continue, but they would all be given a Christian significance. Yule, the northern nature-worshippers’ midwinter festival and the Roman Saturnalia, would become a celebration of the Nativity of Christ, while Midsummer’s Day would celebrate the life of St John the Baptist instead of the radiant sun god, the Norse Baldur.

In Scotland, the celebration of the Celtic spring goddess Bride, would become Candlemas Eve, the eve of the Purification of the Virgin; the Beltane rites in May of summer’s beginning, would be dedicated to the Holy Cross; Lammas in August would continue to celebrate the grain harvest but with Christian rites in churches with loaves of bread and the end of summer, Samhuinn, the most deeply significant festival of the Celtic nature-worshippers, would become a night when all the Christian saints would be hallowed.