Matthew Nicholls

Traces of the huge Roman empire remain all over Europe, from northern Britain to Syria and the coast of north Africa. Anyone who walks the length of Hadrian’s Wall, for example, following it for the 80 miles (130 km) or so from coast to coast through the windswept countryside of northern England, is traveling through what was once a far-flung Roman frontier. Yet even here, hundreds of miles north of Rome’s Mediterranean heartland, there is much of Rome in evidence. The Wall itself, and its string of neat, symmetrical forts, with characteristic bathhouses and headquarters buildings, speak of the power and organization of the Roman army, and its formidable architectural and technological capacity—and also of Rome’s desire to impose itself on new territory, by force if necessary. In and around these outposts, finds of pottery, coins, clothing, altars, and even private letters show how the soldiers and settlers brought with them ways of living, eating, trading, worshipping, thinking, and writing that began to transform Britain—along with many other parts of Europe, north Africa and the Middle East—into a Roman province, leaving a lasting legacy. Such small finds from this great military monument also remind us that historical events are made up from thousands of smaller, private, stories.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, Roman statesman, philosopher, lawyer, and scholar. Remembered as one of the greatest orators and his writings are the epitome of Roman Prose.

This picture is repeated at hundreds of sites, military and civilian, public and private, all over the empire. We also have a rich body of surviving literature from Roman times, transmitted over the centuries in copies of copies—so we can set Hadrian’s Wall in its context by reading what ancient historical writers and poets said about Rome’s conquest of Britain. From epic poetry to history, from speeches to medical treatises to recipes, this rich body of literature allows scholars to explore very different aspects of Rome’s long and colorful history—and newly discovered texts are still turning up, in the dry sands of Egypt, in carbonized books from Herculaneum, and in old libraries.

The Roman empire still imposes on to the modern world with Hadrian’s wall, the defensive fortification in northern England, cutting its way across the landscape nearly 2000 years since its creation.

This study reveals a fascinating people. At times the Romans can seem similar to us, with their concern for home comforts—central heating, proper water supplies, and drains—and their passion for urban life, for good communications, for fine food and wine, for literature, entertainment, and status. But they were also very different. Think of slavery and gladiatorial combat, their world of gods and sacrifices and worship of the living emperor. The grand statues and monuments that filled their public spaces set the mold for many modern cities, but speak of a triumphalism that has now fallen from fashion. In truth, the Romans were both familiar and foreign, which makes the study of their lives and times endlessly fascinating. The contributors to this book ably and enthusiastically take on the challenge of bringing to vivid life the very best and the worst of this ambitious, inventive, cultured, and at times brutal and licentious episode in western history.

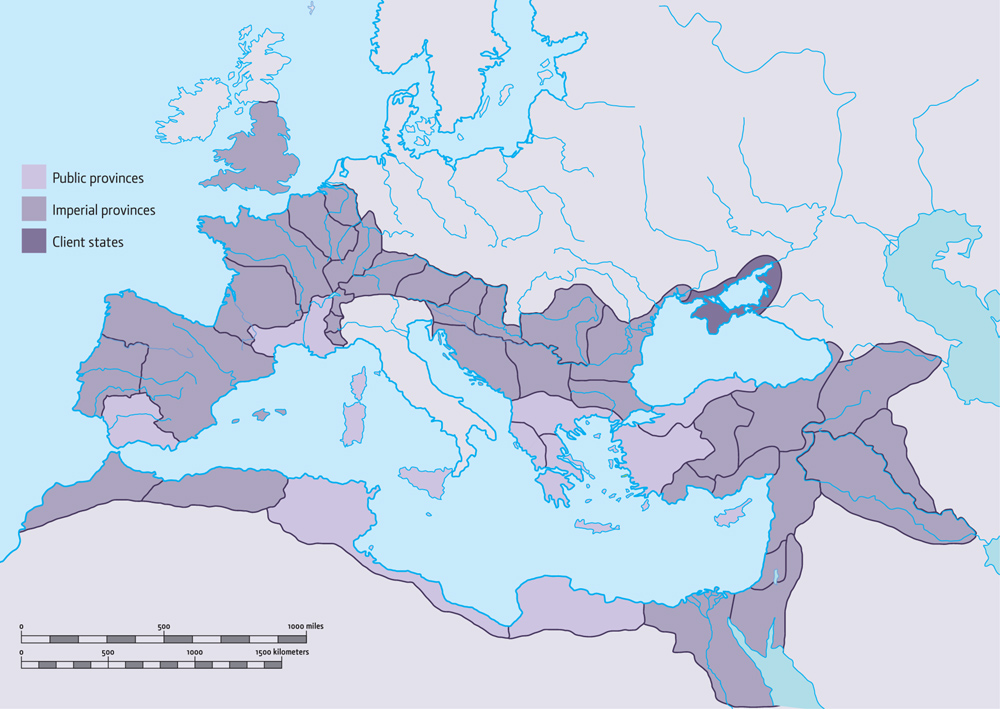

The history of ancient Rome lasted well over a thousand years, from its legendary foundation on April 21st 753 BCE through to the fall of the (western) Roman empire on September 4th 476 CE. Its empire covered much of Europe and parts of north Africa and the Middle East. Its legacy in almost every area of human activity remains to the present day.

This huge span of geography and history can be hard to navigate, but the timeline here shows some major landmarks in Roman history and provides a framework of reference for the rest of the book. Likewise the map, which shows the empire at its greatest extent in the early second century CE, locates Rome itself and charts the Mediterranean world in which its influence eventually spread from the draughty outpost marked by Hadrian’s Wall to the borders of modern Iraq.

753 BCE Foundation of Rome

Legendary foundation date—but, according to some modern archaeology, not far off the mark.

509 BCE Formation of Roman republic

Expulsion of the last of Rome’s kings: a new republican constitution delivered safeguards against excessive individual power.

fifth–third C BCE Growth of Roman power

Roman power spread across Italy through warfare and treaties.

A series of three draining wars against Carthage, Rome’s greatest rival; final victory allowed Rome’s Mediterranean empire to expand.

ca.133–44 BCE Crisis of the republic

A period of unrest and repeated civil war, as Rome’s republican constitution struggled to contain imperial expansion, individual political ambition, and inequality.

Political alliance of three of Rome’s greatest figures: Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus.

March 15th, 44 BCE Death of Julius Caesar

Rome’s dictator felled by senators resentful of his dominance, triggering further civil war.

31 BCE–14 CE Reign of Augustus

Rome’s first emperor. Expansion and consolidation of empire; foundation of a long-lived system of one-man rule.

31 BCE–68 CE Julio-Claudian dynasty of emperors

Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero.

68–97 CE Flavian dynasty

Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian.

Rome’s “best emperor;” under his rule, the empire reached its fullest geographical extent.

96–192 CE Adoptive/Antonine emperors

Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus, and Commodus were emperor by adoption, rather than the transmission of power from father to a son: a largely stable, prosperous period.

193–235 CE Severan Dynasty

A dynasty of African emperors who came to power after a period of civil war.

235–284 CE Third-century crisis

Short-lived emperors, inflation, plague, invasion, discord, and rebellion.

293–313 CE Tetrarchy

Diocletian’s new system of rule by four emperors, which helped to put an end to crisis.

306–337 CE Rule of Constantine

Rome’s first Christian emperor; founded Constantinople (Byzantium) as an eastern capital.

476 CE End of western Roman empire

Waves of invaders brought the western empire to its knees but the eastern empire of Byzantium survived until 1453.

In university departments across the world, specialist classicists and ancient historians cover very diverse aspects of Rome’s life and legacy, studying language and literature, history, art and architecture, and archaeology. The seven chapters of this book aim, very broadly, to explore these key areas.

Compressing this richness into just 50, single-page, topics was difficult, but my hope is that readers will find here both the familiar—legions, gladiators, aqueducts, emperors—as well as new concepts, such as rhetoric, divination, and the way Romans treated people in death as well as in life, suggesting something of the fascinating wealth of material that the archaeological and written records provide.

Each entry is, like Caesar’s Gaul, divided into three parts. The main 30-second history sets out the topic at hand. In a single sentence, the 3-second summary offers a quick synopsis, while a separate panel, the 3-minute excavation, provides a further aspect or something to ponder on. You can dip in and out of the chapters or read them through; each one is prefaced by a glossary to help with unfamiliar terminology and concepts. There are also profiles, one per chapter, of key individuals who, in their time, proved highly influential on society at large, beginning with Caesar himself.

The first chapter, Land & State, opens with the legendary foundation of Rome, and charts its political development from kingdom to republic to empire; it ends with a look at the famous legions that powered Rome’s rise from city-state to global capital. People & Society explores aspects of the way Roman society operated, from the status and interrelation of citizens and slaves, men and women, to the framework of law and governance that bound the empire together. Roman Life considers some of the ways in which these people lived and worked; the fabric of the ordinary and economic life is increasingly as much of interest to ancient historians as the emperors and elite. The succeeding chapters, Language & Literature and Thought & Belief, show us how Roman society spoke, thought, and wrote about itself. The final chapters, Architecture, Monuments & Art and Buildings & Technology reveal the practical side of Roman achievement, its temples, circuses, mosaics, bathhouses, and roads whose monumental remains—like Hadrian’s Wall—cannot fail to captivate and impress the traveler. All roads led to Rome, and we hope that this book will also take you there, by a variety of different routes.

Augustus, the founder of the Roman empire and its first emperor. Best known for the huge expansion that enlarged the empire, but was successful in reforming taxes, developing road networks and rebuilding much of the city of Rome.