Sri Aurobindo took a long leave of absence from his service in Baroda in order to engage himself in the task of awakening the country. So far he had not been participating openly in the Swadeshi Movement; the reason behind it was his absolute aversion to self-publicity. But he could not conceal himself any longer as he publicly accepted the directorship (Principal) of the Bengal National College after resigning from his service in Baroda. This was made possible thanks to his virtuous friend Raja Subodh Chandra Mullick. The fragrant fame of Subodh Chandra’s munificence is present even today all over Bengal. He was as though the Kuvera39 of the national movement. Subodh Chandra had donated one lakh (one hundred thousand) rupees to the National Education Council on condition that Sri Aurobindo should be given a post of professor in the college with a monthly salary of Rs. 150. Sri Aurobindo was then drawing a salary of Rs. 800 per month from his Baroda Service. It has been learnt that after his resignation from the National College, he used to take a sum of Rs. 50 as his salary from the Bande Mataram office.

Sri Aurobindo used to spend very little for his personal use or comfort. While he was in Baroda, a large chunk of his salary used to be spent in purchasing books. Dinendra Kumar has given a detailed account of the simple and unostentatious personal life of Sri Aurobindo in his book entitled Aurobindo Prasanga (About Aurobindo). He was a Sanyasi, enjoying nothing amid wealth, never sorrowing for want of wealth. He never nurtured any demand in his life, while no one except his own near and dear ones knew about his great sacrifice.

The reason for his taking up the professorship at the National Education Council was his conviction, which he developed due to his long association with teaching. He believed that the system of education introduced by the British did not help make a man of character; rather it created a hybrid class called the “Anglo-Indian”. Immediately after his return from England, he made straight and clear remarks regarding the state of national education in an essay published in the Indu Prakash while discussing the imperfections in the character of the Bengali youth. He clearly indicated that the national education was the foundation of the national movement. He wrote valuable essays on the subject, some of which have since been published as a book. The attempt to introduce national education was first made in the era of the Swadeshi Movement and also on the eve of the Non-Cooperation Movement, but the fact remains that we are yet to realise the paramount importance of national education. It is hoped that in independent India the educational institutions will be established in accordance with this lofty ideal.40

Sri Aurobindo could not, however, work long at the National College as disagreement with the authorities cropped up over the students’ admissions. This was an epoch where the students used to be tormented without pity. In many places, they were driven out of the school or college if they even uttered the word “Bande Mataram”. Sri Aurobindo was in favour of admitting without exception these rusticated students at the National College. But the authorities were stubborn, insisting that an educational institution should not get involved in political matters. The National Education Council sought to do away with the imperfections of the government institutions by imparting a truly nationalistic education.41 On 22 August 1907, the students of the National College bid farewell to Sri Aurobindo. On the next day (23 August), Sri Aurobindo delivered a soul-stirring address which reflects, on one hand, his profound love for the country and on the other, the deep respect and veneration he received from his students. He said, “I take it that whatever respect you have shown to me today was shown not to me, not even to the Principal, but to your country, to the Mother in me, because what little I have done has been done for her, and the slight suffering that I am going to endure will be endured for her sake.”42

With this noble resolve, Sri Aurobindo himself volunteered openly in the field of action on the one hand and on the other, a group of young men, inspired by him, took the vow to dedicate their lives to the work of the country. And within a year, the countrymen were wonderstruck at the sight of their supreme sacrifice for the country; the entire country got inundated with a fresh flow of life-force.

Sri Aurobindo had been charged with sedition for writing in the Bande Mataram even before he left the National College (16 August 1907). It was thus impossible for him to conceal himself any longer. Thanks to this charge, his fame spread like the meridian sun throughout the length and breadth of the country. He came forward as the leader of the Nationalist Party in the ideological conflict and the political battle with the Moderate Party. The first direct clash took place in the session of the Bengal Provincial Convention held in Midnapore. Midnapore was the hub of secret associations; as a result, the influence of the Nationalist Party there was absolute.

In the Calcutta Congress held in 1906 under the presidentship of Dadabhai Naoroji, the Moderate Party wanted to bring about only a few minor changes regarding the proposals on the partition of Bengal, boycotting of the British goods, boycotting the British court by settlement of disputes through popular arbitration and national education (The Nationalist Party was, however, not satisfied as they wanted the Congress to take the pledge of complete independence from the British rule). But Sri Aurobindo stood firm like a rock regarding those proposals.

Sometime earlier, a Calcutta weekly entitled the Orient, published, courtesy Hemendra Prasad Ghosh, a letter written by Surendra Nath (Banerjee) to Sri Aurobindo at the time of the Midnapore Conference. The letter was dated 7 December 1907. Surendra Nath, with a view to ironing out the differences between the “Moderates” and the “Extremists” (Nationalists), invited a few leaders of both the parties to deliberate together. But the accord was not reached; the proposals of the Nationalist Party alone were adopted in the open conference.

Just a few days later a direct confrontation between the two parties at the Surat Congress took place. Sir Pherozeshah Mehta, the well-known leader of the Congress residing in Bombay, was whole-heartedly against the Nationalist Party. He wanted to crush it by all means. In this venture, Mr. Morley, the Secretary of India in the British Cabinet of Ministers, was indirectly in his favour as the British government took the policy of strengthening the Moderate Party, and it is this policy that they pursued till the ultimate victory of the Congress. Moreover, it is by taking advantage of the neutrality of the Moderate Party that the British government administered their unopposed and unhindered repressive policy.

A huge meeting was held at Beadon Park, Calcutta, immediately after the Midnapore conference (15 December). At this meeting, the ideals of the Nationalist Party were spelt out. Here for the first time Sri Aurobindo delivered a speech in front of a large group of people. He said that as he was sent to England in his childhood for education, he could not learn his mother tongue very well and was not familiar speaking in his mother tongue either. He therefore considered it best to remain silent rather than speaking in a foreign language. And because of this reason he had not addressed his countrymen for so long.

Subsequently, he delivered quite a few memorable speeches during the period he was in the field of politics. Later, a book containing his speeches was printed. Subsequent to his speech in Calcutta, Sri Aurobindo presided over a meeting of the Nationalist Party held immediately after the bedlam created at the Surat Congress in 1907. On his way back from Surat to Calcutta, he delivered inspiring lectures in some of the cities in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh on the ideals of nationalism. He also explained in those lectures the true nature of national reawakening.

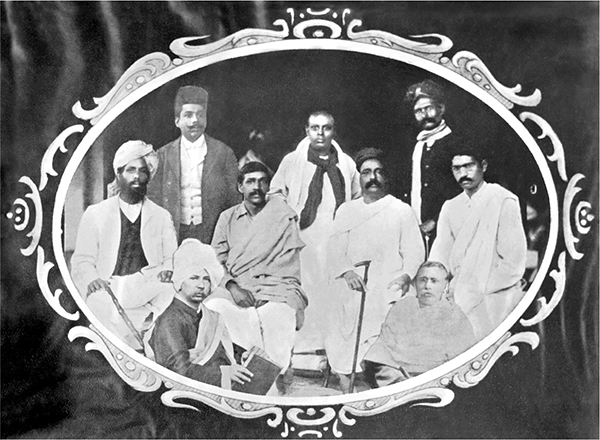

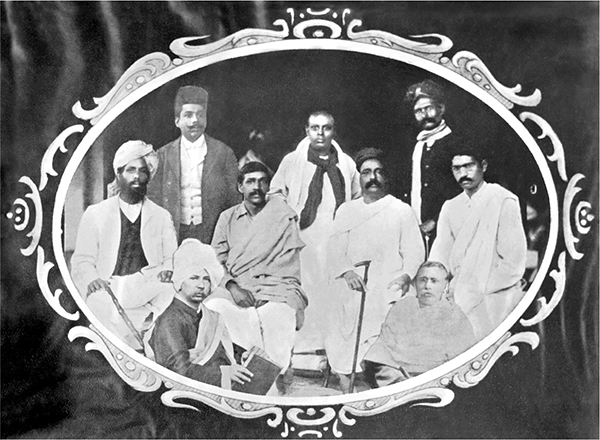

During Surat Congress, 1907. Front row: Ganesh Srikrishna Khaparde, Aswini Kumar Dutt. Middle row: Sardar Ajit Singh, Sri Aurobindo, Lokmanya Tilak, Saiyad Haider Reza. Back row: Dr. Munje, Ramaswamy, Kuverji Desai.

Actually the Surat Congress was supposed to be held that year in Nagpur, but the Moderate Party found that they would not benefit much in that city because of the overwhelming influence of the Maharashtrian politics there. Therefore, the meeting was arranged in the port city of Surat. Never before was there any sort of political activity in Surat; as a consequence, the Moderate Party thought that they would be able to carry out their business peacefully. But that did not happen because of the presence of Lokmanya and his party workers as well as the presence of Sri Aurobindo and his followers. Sri Aurobindo arrived in Surat with his colleagues of the Bande Mataram office and some other followers.

The Congress session got under way amid apprehensions of an imminent political Kurukshetra (war). In those days, the provincial committees did not have the power to elect the President of the Congress; the authorities used to select a leader beforehand as the would-be President who in the Congress session itself used to be nominated. Surendra Nath, on the part of the Moderate Party, proposed the name of Sir Rash Behari Ghosh, whereas from the side of the Nationalist Party, the name of Bal Gangadhar Tilak was proposed. This resulted in tumultuous altercations and soon pandemonium erupted. Shoes, chairs and other objects were hurled, a few leaders were hurt and the public started scurrying towards the platform where the leaders were seated. Surendra Nath, in his autobiography (A Nation in Making), has written:

As a past President of the Congress, it was my duty to propose Sir Rash Behari Ghosh as President. I had often before performed this duty with the general consensus and approval of the Congress. It was not to be this time. I remembered the incidents of the Midnapore Congress (I had stopped the disturbances there) and there were attempts to obstruct my speech repeatedly. For me this an unprecedented experience, because whenever I used to rise to the dais after the initial cheering reigned complete silence.

Surendra Nath continues after presenting an account of the Surat turmoil:

Even though the public rushed towards the dais I remained seated there. Some of my friends saved me. Later, Sir Pherozeshah Mehta and some other were taken at the rear of the tent and the police cleared out all the people from the pandal. In this way ended a memorable chapter of the Congress and another epoch commenced.

(Translated from the Bengali text in the book and not a verbatim reproduction of the original speech in English.)

At this new juncture, the Congress began to inch towards independence and gradually became so strong that it could last through innumerable trials and tribulations for its ultimate goal—a free India. The nation completely shunned the policy of supplication and the fame of the Congress spread all over the world. In due course, the Congress turned out to be exclusively a peoples’ party. But very few people of today would remember that this transformation of the Congress was set in motion through the actions of Sri Aurobindo and Tilak.

Be that as it may, Sri Aurobindo remained calm and collected in the midst of the chaos and commotion at Surat. Barindra Kumar has written that at a time when a section of the people attending the meeting started crying for blood, and shoes, sticks, chairs, etc., were brandished about viciously, Sri Aurobindo was seen seated with a serene and still face, not showing the least sign of being perturbed; he did not even care for his own protection. Eventually, as the police came and made the pandal free from the disorder, Sri Aurobindo along with a few of his colleagues came out in the open. A meeting of the Nationalist Party was convened immediately thereafter and Sri Aurobindo was invited to preside over it. Rash Behari Ghosh failed to get an opportunity to deliver his speech. His speech was later published in the Bande Mataram with the heading “Undelivered Masterpiece”.

Apparently it would seem on the surface of it that the internal strife of the Congress Party undermined the cause of the country, but the subsequent events that took place in the next few years proved this strife actually resulted in providing the national movement a firm footing. It is true that after the Surat session, the Congress Party dimmed for a few years; this is because the Nationalist Party was in disarray on account of the repressive measures of the British government. But no sooner had Tilak returned from exile than the movement of Swaraj was set in motion and, with him, the Home Rule Movement by Annie Besant kept the country agog. Thereafter came Gandhiji and then started the Non-Cooperation Movement ending up with the freedom movement. Until 1916, the Congress Party was in the hands of the Moderates but in the Lucknow Congress held in the same year, the Congress was united after a temporary pause in “groupism”. However, seven years before this union, when the political factionalism was at its height, Sri Aurobindo made a startling revelation, indicating this unity in an essay published in the Dharma. Such was his political foresight. However, realising that the heat of politics was increasing to a degree, the Moderates could not any longer remain in the Congress Party. In 1917, on the occasion of the Calcutta Congress, factionalism started and in the very next year, the Moderate Party abandoned all contact with the Congress and founded a separate political party. But from then on, the influence of the Moderate Party started dwindling and at present [1939] there is no trace of it. After independence every one joined the bandwagon of the Congress Party.

After returning from Surat, Sri Aurobindo started propagating the ideals of the Nationalist Party with renewed ardour and intensity. He delivered a few touching speeches on the ideals of the Nationalist Party in Bombay and in some places in Madhya Pradesh explicating therein why the factionalism in the Congress Party was inevitable. About a month before he was arrested, on 10 April 1908, in an address delivered in Calcutta on the united Congress, Sri Aurobindo declared that it was by God’s will that the Surat Congress ended in a fiasco and that if the Congress could reunite, then it would happen by His will. He threw light particularly on the fact that the Congress was not broken because of any personal reasons; the factionalism came to the fore because of a few obvious basic problems. Firstly, irregularity in the election of the President; secondly, efforts made by certain parties to negate the four proposals agreed upon in the Calcutta Congress the previous year (1906); thirdly, the attempt to change the fundamental ideal of the Congress by trampling the stronger (Nationalist) party by virtue of superior numbers of the local (Surat) party. In a situation like this, there was no other alternative but a direct confrontation. Tilak proposed that in order to constitute the Congress according to the rules, a separate committee had to be formed and it is this committee that would elect the President of the session. The other party, that is the Moderate Party, without giving an opportunity to Tilak to raise the proposal, suddenly declared that Rash Behari Ghosh had been unanimously elected President. When there were concrete differences of opinion in this respect, then how could it be said that the President was elected unanimously?

Thereafter, Sri Aurobindo observed that the Nationalist Party was ready to overlook all these irregularities on condition that the other Party agreed to form a Joint Congress and accept the proposals adopted at the Calcutta Convention. If they declined, then they would be held fully responsible for creating an institution of a fragmented group breaking away from the Congress. He remarked, “Our policy is that we will work in our establishment as a separate party but we want a Joint Congress for the whole nation.”