1 President Kennedy watching a TV broadcast of the first U.S. manned spaceflight, of Alan Shepard, on May 5, 1961. With Kennedy, from left: Vice President Johnson; Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.; Admiral Arleigh Burke; Kennedy; First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. They are in the office of Kennedy’s secretary, Evelyn Lincoln.

2 President Kennedy speaks to NASA staff in Houston, in front of an early mock-up of the lunar module, during a tour of NASA facilities on September 11 and 12, 1962. Kennedy is holding a small model of the Apollo capsule that NASA staff gave him. Just to his left, behind him, is NASA administrator James Webb.

3 Charles Stark Draper, a legendary MIT professor, researcher, and pilot, led the invention and refinement of the navigational equipment that allowed Apollo to fly to the Moon.

4 Doc Draper with Ralph Ragan, one of his senior managers for MIT’s Apollo program. MIT had the contract to design the computers and navigation equipment for Apollo, supervise their construction, and write the computer programs that flew the spacecraft to the Moon. Draper and Ragan are in front of Wolfie’s in Cocoa Beach, Florida, a well-known 1960s deli, attached to the Ramada Inn, near NASA’s Cape Kennedy launch facilities.

5 Under the shroud is a secret inertial navigation unit being installed on a B-29 bomber, part of a fleet used by MIT. In February 1953, the unit guided the plane coast-to-coast without any outside information, and without the pilot touching the controls, proving the practicality of inertial navigation.

6 A factory worker at Raytheon in Waltham, Massachusetts, hand-weaving a “rope core” memory unit for the Apollo computer. Using this painstaking technique, it took six weeks to manufacture the software for a single Apollo computer.

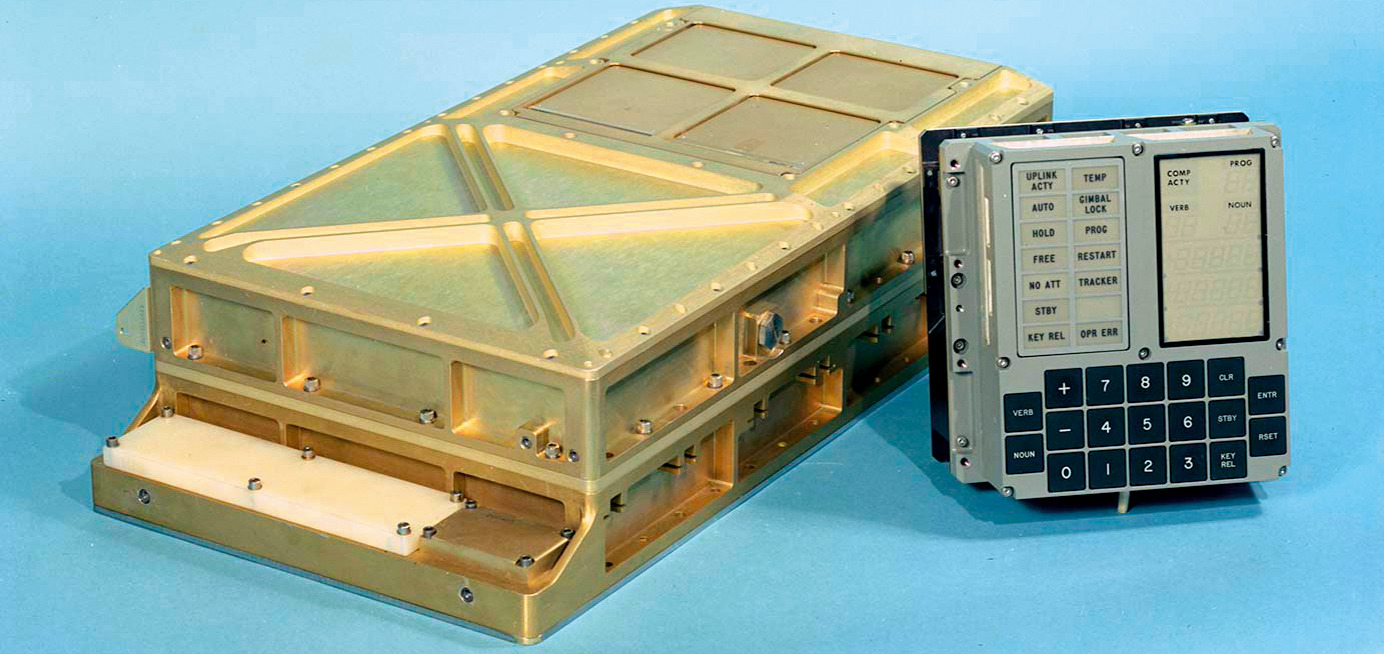

7 Apollo’s flight computer and the display and keyboard used to run it. The computer weighed seventy pounds with the metal case, and was two feet long and one foot wide. At the time, it was one of the smallest, fastest, most nimble computers ever.

8 NASA engineer John Houbolt explaining an innovative technique to fly astronauts to the Moon and back. Houbolt fought a years-long battle to get NASA to seriously consider this idea for flying to the Moon. The method Houbolt advocated, called “lunar-orbit rendezvous,” was ultimately the one NASA used.

9 NASA engineer Bill Tindall, left, in Mission Control during an Apollo mission, with flight director Gene Kranz. Tindall—almost never photographed or written about—was critical to mastering the orbital mechanics necessary to fly to the Moon, and to helping MIT get the flight software written. Right, Tindall in a flight simulator for the Space Shuttle, which he worked on after Apollo.

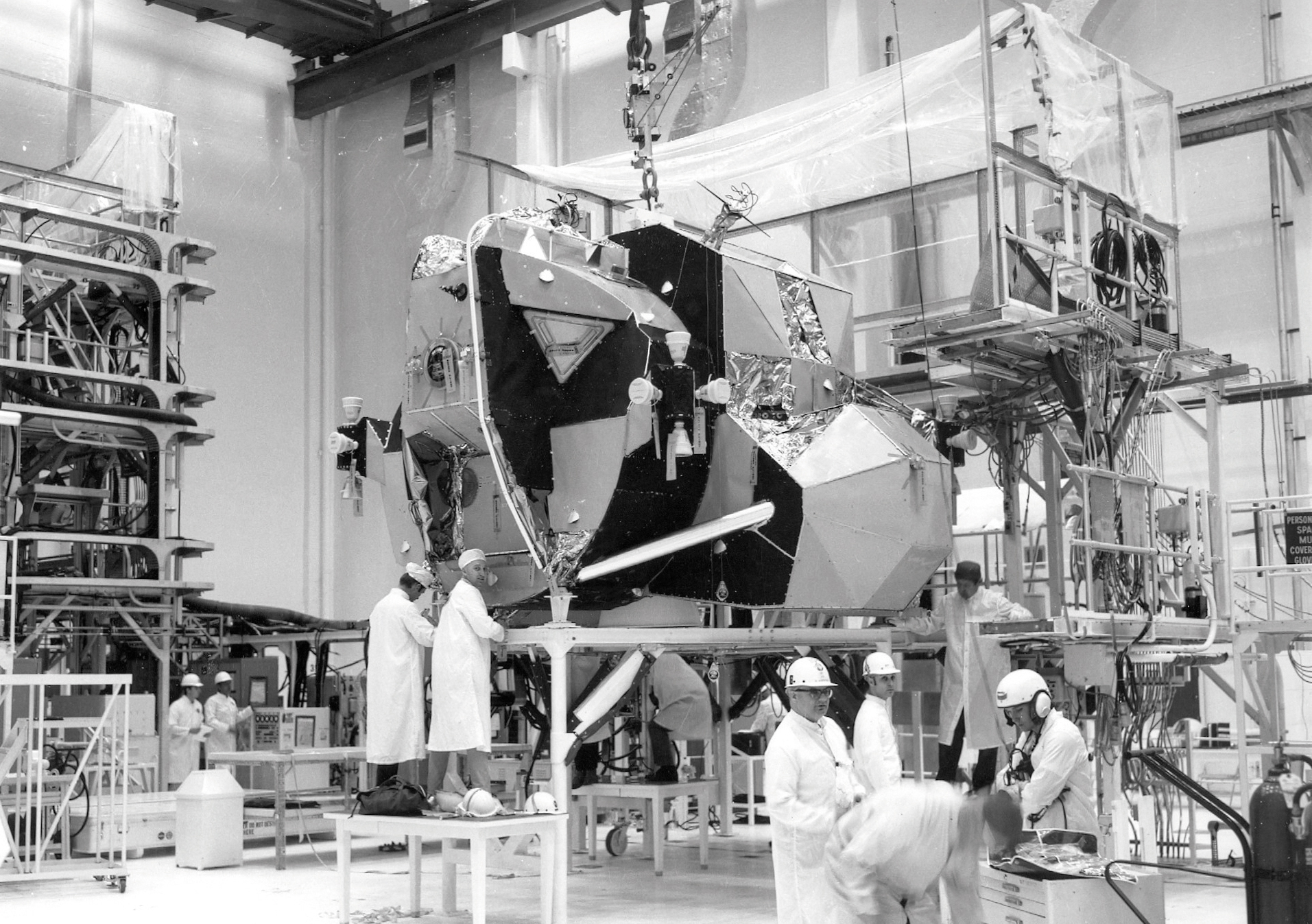

10 The lunar module under construction in clean-room conditions at the Grumman factory on Long Island. Top, an LM upper stage, outer skin in place. It contained the crew compartment, and had its own engine and fuel tank (the big sphere visible uncovered in the lower photo), for blasting off from the Moon.

Below, the entire LM, with upper stage mated to the boxy descent stage. Visible are struts for mounting the LM’s legs, not yet installed.

12 The lunar module more fully assembled, with some areas covered in the characteristic shiny Mylar insulation, suspended from a crane in the assembly building. The LM was often referred to as “spindly” or “gawky,” but astronauts said that in space it handled like a sports car.

13 A rare picture of Thomas J. Kelly (white shirt, in front), chief engineer for the LM at Grumman, whom NASA called “the father of the lunar module.”

In this photo from Apollo 11, Kelly is staffing a support room in Mission Control. To his left is Owen Maynard, his counterpart as LM project manager for NASA. Said Kelly of the LM, whose design and construction he oversaw: “How I wished to be a stowaway in that tiny cabin.”

14 When the Apollo 11 LM computer started sounding alarms, Jack Garman had twenty seconds to assess how serious they were. Garman, at right in the top photo, had created a handwritten list of computer alarm codes (above right) so he would know how serious any alarm was. He gave the okay, helping save the Apollo 11 Moon landing seconds before touchdown.

Top, Garman receiving an award from Chris Kraft, head of Mission Control. Below, the Mission Control support room where Garman worked during flights—he is in the front row of consoles, second from left, in a sport coat.

16 An astronaut at the controls of his spaceship: Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, Apollo 11 LM pilot and the second man on the Moon, in the cockpit of Eagle. Clearly visible are the LM’s distinctive triangular windows, and between them the spaceship’s main control panel. Above Aldrin’s head is a rolled-up sunshade for the left-side window. Note the paper floating near the top of the cockpit. Apollo astronauts carried paper checklists, mission plans, and star charts to the Moon. At bottom center are two white bags, to the left and right—spacesuit helmets, stowed in their protective covers.

Aldrin is floating in the ship during an initial inspection in lunar orbit. This is a mosaic of seven photos, shot by Neil Armstrong on July 19, 1969, and assembled by Jon Hancock. (The ghostly image of Aldrin’s “extra arm” is an artifact from one of those photos, in which Aldrin was facing the other way.)