Rainwater drummed against the high stained glass windows of Redwall Abbey. It had poured down since midnight of the previous day. Even the hardiest of workbeasts had left their outdoor tasks for dry ones indoors. Mhera and her faithful friend Gundil emerged from the kitchens to sit upon the cool stone steps to Great Hall. Brushing a paw across her brow, the ottermaid blew a sigh of relief. “Whooh, goodness me, it’s hot in there, Gundil!”

The mole undid his apron and wiped the back of his neck. “Yuss, marm. If’n oi’d stayed thurr ee moment longer they’m be ’avin’ ee roastified mole furr dinner. Hoo aye!”

Filorn’s call reached them from the kitchens. “Mhera, Gundil, come and take this tray, please.”

She met them just inside the kitchen entrance. Filorn was no longer a young ottermum. Her face was lined and she stooped slightly, but to her daughter she still looked beautiful. Mhera, who was now much taller than Filorn, touched her mother’s workworn paw gently.

“Why don’t you finish in there for the day? Go to the gatehouse and take a nap with old Hoarg in one of his big chairs.”

Filorn dismissed the suggestion with a dry chuckle. “Food doesn’t cook itself, you know. I’m well able for a day’s labor. Huh! I can still work the paws from under either of you two young cubs!”

Gundil tugged his nose in courteous mole fashion. “Hurr, you’m surpintly can, marm. Boi ’okey, you’m a gurt cooker, all roight. But whoi doan’t ee take a likkle doze?”

Filorn presented them with the tray she was carrying. “If I listened to you two I’d never get out of bed. Now take this luncheon up to Cregga Badgermum, and be careful you don’t trip on the stairs. Gundil, you carry the flagon and Mhera can take the tray.”

*

Cregga was dozing in her chair when she heard the approaching pawsteps. “Come right in, friends,” she called. “Gundil, you get the door. Put the flagon down in case you drop it!”

They entered, shaking their heads in wonder. Cregga patted the top of the table next to her overstuffed armchair. “Put the tray down here, Mhera. Mmmm, is that mushroom and celery broth I can smell? Filorn has put a sprinkle of hotroot pepper on it, just the way I like it.”

She checked Gundil. “Don’t balance that beaker on the chair arm. Put it there, where I can reach it easily.”

The mole wrinkled his snout. “Burr, ’ow do ee knoaw, Creggum? Anybeast’d think you’m ’ad ten eyes, ’stead o’ bein’ bloinded.”

She patted his digging claw as he replaced the beaker. “Never you mind how I know. Hmph! That door has swung closed again. Open it for me, please, Mhera my dear. This room can get dreadfully stuffy on a rainy summer’s day.”

Mhera opened the door, but it would not stay open. “Warped old door. It’s starting to close again, Cregga.”

The badger blew on her broth to cool it. “Have a look in the corner cupboard. I think there’s an old doorstop in there, on the bottom shelf.”

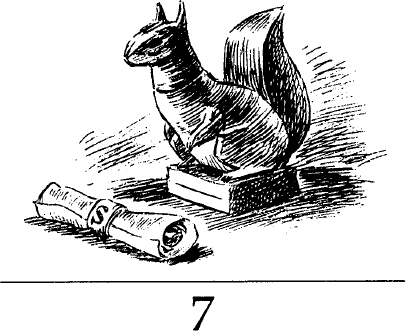

Mhera did as she was bidden, finding the object immediately. “Oh, look, it’s a little carved squirrel, made from stone, I think. No, it’s made from heavy dark wood. Where’s it from?”

Cregga dipped a barley farl in her broth and took a bite. “It belonged to Abbess Song. Her father, Janglur Swifteye, carved it from a piece of wood he found on the seashore. That was longer ago than I care to remember. Though I do recall that when Song was old she used it as a doorstop too. She gave it to me before she passed on. Why don’t you take it, Mhera? When Song was young she was a lot like you in many ways. I was going to leave it to you when my time comes, but you might as well have it now.”

Mhera took the carved statuette to the window and turned it this way and that, admiring it. “Thank you, Cregga, it’s lovely. Abbess Song’s dad must have been a very skilled carver, it looks so alive. What a pity it ended up as just a doorstop. Here, Gundil, take a look.”

The mole took hold of the carved squirrel and inspected it closely, sniffing and tapping it with his digging claws. “Burr, wunnerful h’objeck. ’Tain’t no doorstopper, tho’. This ’un’s a bokkle.”

Mhera looked at her molefriend curiously. “A bottle? You mean a sort of flagon?”

Gundil nodded sagely. “Ho urr. Oi see’d one afore. Moi ole granfer ’ad one shapened loike ee moler. Kep’ beer in et ee did.”

Cregga poured herself cold mint tea. “Tell us then, Gundil, how can a statue be a bottle? How would you get anything into it? Where’s the top, where’s the neck?”

The mole grinned from ear to ear with delight. “Hurrhurr, marm, see, you’m doan’t be a knowen everythin’ arfter all. Ee top is ee head an’ you’m turn ee neck. Lukkee!” He twisted the statuette’s head, and it came away from the neck. Inside had been cunningly carved out to form a bottlelike container.

Gundil passed it to the badger, and Cregga felt it all over with her huge paws. The Badgermum’s voice went hoarse with excitement. “Mhera, your paws are daintier than mine. There’s something inside. Can you reach in and get it out?”

Mhera’s paw fitted easily into the cavity. She brought forth a scroll, held by a ribbon with a red wax seal. “It’s an old barkcloth parchment with a ribbon and seal!”

Cregga abandoned her lunch and sat up straight. “Is there a mark upon the seal?”

Mhera inspected the seal. “Yes, Cregga, there’s a letter S with lots of wavy lines going through it. I wonder what it means?”

The Badgermum knew. “The Abbess’s real name was Songbreeze. Her sign was the S with breezes blowing through it. Can you see properly, Mhera? The light in here means nothing to me. Gundil, run and fetch a lantern, please. Hurry!”

Clearing the tray from the table, they placed both lantern and scroll upon it. Cregga felt the seal with her sensitive paws. It had stuck to both scroll and ribbon.

“What a pity to break this lovely thing. I would have liked to keep it, as a memento of my old friend Abbess Songbreeze.”

“Yurr, you’m leaven et to oi, marm, oi’ll get et furr ee!” From his belt pouch, Gundil took a tiny flat-bladed knife, which he used for special tasks in the kitchen. It was as sharp as a freshly broken crystal shard. Skillfully he slit the faded ribbon of cream-colored silk and slid the blade under the wax, cleverly lifting it away from the scroll in one undamaged piece.

Mhera held it up admiringly. “Good work, Gundil. It looks like a scarlet medallion hanging from its ribbon. Here you are, Cregga.”

Taking it carefully, the Badgermum smiled with pleasure. “I’ll treasure this. Thank you, Gundil. I’m sure nobeast but you could have performed such a delicate operation!”

Gundil scratched the floor with his footpaws, wiggling his stubby tail furiously, which moles will often do when embarrassed by a compliment. “Hurr, et wurrn’t nuthin’, marm, on’y a likkle tarsk!”

Mhera was practically hopping with eagerness. “Can we open the scroll now, Cregga!”

The blind badger pulled a face of comic indifference. “Oh, I’m feeling a bit sleepy. Let’s leave it until tomorrow.” She waited until she heard her friend’s sighs of frustration. “Ho ho ho! Go on then, open it. But be sure you read anything that’s written down there loud and clear. I wouldn’t miss this for another feast. Well, carry on, Mhera!”

The barkcloth had remained supple, and Mhera unrolled it with meticulous care. There were two pieces. A dried oak leaf fell out from between them, and she picked it up.

“There’s two pages of writing. It’s very neat; Abbess Song must have been really good with a quill pen. A leaf, too.”

Cregga held out her paw. “Give me the leaf.” Holding it to her face, she traced the leaf’s outline with her nosetip. “Hmm, an oak leaf. I wonder if it’s got any special meaning? What does Song have to say? Come on, miz otter, read to me!”

Mhera began to read the beautifully written message.

“Fortunate are the good creatures,

Dwelling within these walls,

Content in peaceful harmony,

As each new season falls.

Guided in wisdom by leaders,

One living, the other long dead,

Martin the Warrior in spirit,

And our chosen Abbey Head.

’Tis Martin who chooses our Champion,

Should peril or dangers befall,

Or Abbot to rule Redwall?

I was once your Abbess,

A task not like any other,

To follow a path in duty bound,

I took on the title of Mother.

Mother Abbess, Father Abbot,

They look to you alone,

For sympathy, aid, and counsel,

You must give up the life you’ve known.

To take on the mantle of guidance,

As leaders before you have done,

Upholding our Abbey’s traditions,

For you alone are the One.”

There was a brief silence, then Cregga repeated the last line. “For you alone are the One!”

Mhera looked perplexed. “Me?”

Gundil climbed up and sat on the arm of Cregga’s chair. “Wull, et surrpintly bain’t oi. This yurr moler wurrn’t cutted owt t’be no h’Abbess, no miz, nor a h’Abbot noither!”

Cregga chuckled, stroking the mole’s furry head. “You’ve got a point there, friend. I couldn’t imagine you in the robes of an Abbot.”

Gundil folded his digging claws over his plump stomach. “Nor cudd oi, marm, gurt long flowen garmunts, oi’d trip o’er an’ bump moi ’ead!”

Mhera held up a paw for quiet. “There’s writing on this other page too, that’s if you want to hear me read it?”

Gundil spoke out of the side of his mouth to Cregga. “Yurr, she’m a h’Abbess awready, bossen uz pore beasters abowt. We’m best lissen to miz h’otter!”

Mhera gave them a look of mock severity and coughed politely. “Ahem, thank you. Now, there are several things written down here. First of all it says this. Oak Leaf O.L.”

Cregga passed her the leaf. “Here’s the oak leaf. Take a close look at it, Mhera.”

The ottermaid inspected it. “O.L. It’s a bit faded, but Abbess Song wrote those two letters here on the leaf.”

Gundil cast his eye over the two carefully inked letters. “Ho urr. O.L. stan’s furr h’oak leaf. Wurr ee h’Abbess a-tryen to tell us’n’s sumthink?”

Cregga gave his back a hearty pat. “That’s sound mole logic, my friend. Read on, Mhera!”

The next lines Mhera read affirmed what Gundil had guessed.

“Though I am no longer here,

I beg, pay heed to me,

O.L. stands for Oak Leaf,

A.S. leaves you her key.

A.S.”

Cregga caught on fast. “A.S. Abbess Song! It’s simple really.”

Mhera interrupted her. “Not as simple as you think. Listen to the second verse.

“If you would rule this Abbey,

G.H. is the place to be,

At the T.O.M.T.W.

Look to the L.H.C.”

Gundil scratched his snout in puzzlement. “Hoo urr, they’m a gurt lot o’ letters!”

Mhera smiled confidently. “Let’s go down to the gatehouse and find out, shall we!”

Cregga eased herself from the big armchair. “Gatehouse?”

Mhera took her friend’s paw. “Of course. G.H., gatehouse. Lend a paw here, Gundil.”

Even with their help, the Badgermum had great difficulty managing the stairs. When they reached the bottom step Cregga sat down, shaking her huge striped head.

“You two carry on to the gatehouse. I’ll wait here. I’m not as spry as I once was. Don’t get that parchment wet with rain.”

Mhera tucked the scroll carefully into her apron pocket. “But Cregga, don’t you want to come with us and find out what it all means?”

The blind badger sighed wearily. “I’ll only slow you down. You can let me know what you found out when you come back. Go on now, you two.”

When they had gone, Boorab, who had been banished from the kitchens, sauntered by. The gluttonous hare was munching on a minted potato and leek turnover, which he hid hastily as he caught sight of Cregga.

“Er, how dee do, marm? Bit of inclement weather, wot wot?”

She held out her paw. “Help me up, please.” As the badger was hauled upright, she sniffed the air. “I smell mint. Have you been plundering in the kitchens again?”

The hare’s look of injured innocence was wasted on a blind badger. His earbells tinkled as he shook his head stoutly. “Shame on you, marm. I haven’t been within a league of your confounded kitchens. I was down in Cavern Hole, composing a poem to your wisdom an’ beauty an’ so forth. But I’ll bally well scrap the whole thing now. Hmph! Accusin’ a chap of my honest nature of pinchin’ pastries, wot!”

Cregga shrugged. “But I can still smell mint and I know that Friar Bobb is baking minted potato and leek turnovers for dinner tonight.”

Boorab sniffed airily. “Well, of course you can jolly well smell mint. I always put a dab or two of mint essence behind each ear after my mornin’ bath. Gives a chap a clean fresh smell, doncha know?”

Cregga inclined her head in a small bow. “Then forgive me. I apologize heartily. We’ll share a turnover or two at dinner this evening. I like them best when the crust is dark brown and the potatoes have melted into the leeks.”

Boorab fell into the trap unthinkingly. “Well, they’re not quite at that stage yet, marm. The potato is still a bit lumpy and the crust is only light brown.”

As he bit his lip, the badger patted Boorab’s pocket, squashing the turnover against his stomach. “Aye, I’d leave them to cook properly, if I were you,” she growled. “As far as I’m concerned, you’re still on probation at Redwall.”

The hare watched her lurch slowly off. Dipping his paw into the mess inside his pocket, he sucked it resentfully. “Fifteen blinkin’ seasons’ probation. Bit much for any chap, wot!”

*

Grass squelched underpaw in the rain as Mhera and Gundil hurried across the front lawns to the little gatehouse by the Abbey’s main outer wall entrance. Gundil was about to knock when old Hoarg opened the door.

“What’re you two doin’ out in this? Yore wetter’n fishes in water. Come in, come in!” He tossed them a big towel to dry their faces. “So then, what brings ye here, Miz Mhera?”

Taking the parchment from her pocket, Mhera spread it on the table and told the ancient dormouse gatekeeper the whole story to date. Placing small rock crystal spectacles on the end of his nose, Hoarg inspected the document, staring at it for what seemed an age. The two friends maintained a respectful silence. Hoarg sat in an armchair and mused awhile. “Well then, you’ve come to my gatehouse to search for clues?”

Gundil sounded a trifle impatient. “Yurr, uz ’ave, zurr. May’aps you’m ’elp us’n’s?”

The old dormouse nodded sagely. “Oh, I’ll help ye all right. But first tell me, Mhera, do you think wisdom, patience, an’ the ability not to rush at things would be good qualities in an Abbess?”

Mhera was very fond of the old gatekeeper. “Oh, I do, sir. Why d’you ask?”

Pursing his lips, Hoarg stared out of the window at the rain. “Hmm. Learning, too, I wouldn’t wonder. Gatehouse is one single word, you know, not two separate ones. So this place would only be referred to as a single G on your scroll. Now I want you to take your time and think. Name me a place at Redwall Abbey that starts with the two letters G and H.”

Mhera slammed her paw down on the table as realization hit her. “Great Hall, of course. Come on, Gundil!”

Hoarg’s voice checked them as they dashed for the door. “There you go, rushin’ off without thinking. I never make a move before I think anythin’ out. I’ve solved the next bit of that puzzle. I know what T.O.M.T.W. means.”

Mhera grabbed the scroll and stuffed it in her apron pocket, her paws aquiver with excitement. “Oh, tell us what it is, sir, please please tell us!”

“Only if you promise to go a bit slower in the future and stop to reason things out, instead of hurtlin’ ’round like madbeasts.”

“You’m roight, zurr. Us’n’s be loike woise snailers frumm naow on, oi swurr to ee!”

Hoarg removed his spectacles and put them away slowly. “I could be wrong at such short notice, but I think that T.O.M.T.W. means Tapestry Of Martin The Warrior.”

With his cheek still damp from the kiss Mhera had planted on it, Hoarg sat back in his armchair. He heard the door slam and the two sets of footpaws pounding away over the drenched lawn toward the Abbey building. The dormouse chuckled. “Ah, the speed and energy of younger ones. I’m glad I lost it a long time ago.”

Closing his eyes, he went into a comfortable doze.

*

On entering the Abbey, wet and panting, the two friends spied Cregga. She was sitting on the floor of Great Hall, gazing up at the tapestry. Mhera skidded to a halt beside her.

“Cregga, how could you! Listen to that rain out there. You let us run all the way to the gatehouse and back!”

The Badgermum turned her sightless eyes toward them. “It came to me while I was sitting on the stairs, but you two had already charged off. What did Hoarg have to say?”

Gundil flopped on the floor and began drying his face on Cregga’s habit sleeve. “Lots o’ things abowt gooin’ slow an’ payin’ ’tenshun an’ lurrnen t’be woisebeasts, marm.”

The badger dried Mhera’s face on her other sleeve. “Good old Hoarg. I remember he was slow and methodical even when he was a Dibbun. Well, here we are. G.H. Great Hall, and there it is, T.O.M.T.W., the Tapestry Of Martin The Warrior. But I haven’t the foggiest notion of what L.H.C. means, have you?”

Mhera stared up at the likeness of Redwall’s greatest hero, armor-clad and armed with a sword. “No, I’m afraid not. There’s one other thing that puzzles me also. What are we supposed to be searching for?”

Cregga put out a paw and touched the tapestry. “Wisdom maybe, knowledge perhaps, L.H.C. certainly, but where do we find it?”

“Hurr, marm, mebbe us’n’s jus’ sit ’ere an’ arsk Marthen ee Wurrier. Thurr wurr never ee woiserbeast than ’im.”

Mole logic won the day again. They sat staring at the mouse warrior, each with their own thoughts.

L.H.C.

Lower Hall Cavern?

Little Hot Cakes?

Lessons Have Commenced?

Let Him Choose?

The image of Martin began to swim and shimmer in front of Mhera’s eyes. It had been a long hard day, working in the kitchens, dashing about with trays, helping Cregga downstairs, rushing to and from the gatehouse. Cregga was already dozing as Mhera leaned her head against the badger’s lap and fell into slumber, still pondering the puzzle.