, thought Ah Thloo, Aiya

ELEVEN

Father Rejuvenated, Mother Baptized

AH THLOO: MONTREAL, 1965

It was late on a winter afternoon, and Ah Dang and Ah Thloo were shopping downtown for Christmas presents. It would take them more than an hour to get home, so he said to his wife, “You must be hungry. Let’s go have something to eat.” She thought, Dinner out. What a pleasant treat!

Ah Dang had very pedestrian tastes in food. He ate like a Canadian teenager: Kraft peanut butter and orange marmalade on whole wheat bread, Velveeta cheese, kosher all-beef frankfurters, and applesauce. Every day, at home or at work, he drank either Red Rose or Po-Neh tea. If he was at home for an “offu day,” which is how the family referred to his day off work, he would bake an apple pie or roast a joint of beef. Unless it was at a banquet, he rarely ate in Chinatown. He used to say he was tired of eating restaurant food.

A typical “offu day” with the children, playing at the War Memorial on Park Avenue, 1956.

T.S. WONG, MONTREAL

On the shopping afternoon, he took his wife to a restaurant on St. Catherine Street. He ordered coffee and a muffin for himself and asked her what she wanted. She could not read the menu and had no idea what to order. Shocked and disappointed, all she could murmur was, “I’m not hungry.”

• • •

AH THLOO AND AH DANG: MONTREAL, 1955–1966

Ah Thloo and Ah Dang were celebrating their first Chinese New Year together when their third and last child was conceived. It was a surprise, for she was forty-four and he was fifty-three, ages when most of their predecessors had become grandparents.

For the first time, both the pregnancy and the birth were hard on Ah Thloo. She had to give birth in a hospital: she was weak and produced no milk. Their daughter was born on October 12, 1955. The hospital required that a name for the child be recorded on a birth certificate before the mother and baby could be released to go home. It was disconcerting for the parents, as they would normally have waited for the one-month Choot Ngiet Gat How ceremony to announce a name. But these were the Canadian customs.

A pregnant Ah Thloo at the Botanical Gardens with Ah Wei, 1955.

GD WONG, MONTREAL

Like her sister before her, the baby was given the middle name of Quen. Her first name was May, meaning “beautiful.” Coincidentally, the word “may” in Chinese also sounds like the word for “final” or “last.”

A month after the baby was brought home, Ah Dang wrote to inform his mother and parents-in-law about the birth of another granddaughter and enclosed money for celebratory feasts. Despite Ah Thloo’s inability to breastfeed the baby, and their initial fears for its health, the child thrived, first on formula, then on cow’s milk. Ah Dang reported that the baby was fat and active when presented to their friends, on the occasion of her one-month haircutting event.

Ah Tew May wrote back to say she was glad her Gowdoy, as she always referred to her grandson, Ah Wei, had a new playmate. Ah Shee, Ah Thloo’s mother, then aged seventy-five, wrote on behalf of Ah Poy Lim, seventy-eight, and herself, sending polite congratulations to their son-in-law and daughter. Three years later, Ah Shee would be dead, and her husband would be living as a hermit in a hut away from the village, visiting his former home only to get food. He died in 1960, at the age of eighty-three, a once proud and capable man, overcome by the unrelenting social, economic, and political upheavals of his times.

Christmas at Bagg Street, 1959.

ROBERT WONG, MONTREAL

The younger generation, when informed by Ah Thloo, responded with enthusiasm about the baby and with concerned inquiries about her health. If her daughter Ah Lai, goddaughter Ah Ngan Jean, or godson Ah Sang were surprised, no one mentioned it, and each sent a small gift along with good wishes. Not too long afterwards, Ah Lai started her own family.

Ah May’s birth rejuvenated Ah Dang. He gave her a twenty-four-carat gold charm bracelet, hung with delicately tinkling bells and small animals at her one-month ceremony, to welcome her. He now had the chance to witness a child of his grow from infancy to school age and adulthood. At first, whenever he got home from work late at night, he would relax by smoking and watching her as she slept. When she coughed each time he lit a cigarette, he stopped, “cold turkey,” a pack-a-day habit he had started more than thirty years earlier. As she grew, his hands would search for hers to hold whenever they went out. He was making up for lost time, when there was no family member he could touch and cherish. He recorded the lives of his two younger children on his camera and, later, in movies.

Shortly after the birth of his daughter, Ah Dang bought a three-storey residential building on Bagg Street, a short side street off St. Laurent Boulevard, in an area of Montreal known as The Main. Since they had come to Canada, the Wong family had been living in rented rooms on de Bullion Street, but when Ah Thloo mentioned that rats had brushed her feet, scurrying around the bedroom while she fed the baby at night, it was enough to spur Ah Dang to find another place.

The house cost fourteen thousand dollars; he paid half down and got a mortgage from the vendor, Myer Patofsky, a tailor, at 6 per cent interest for the remainder, until 1972. It was thirty-four years to the month after he had landed in Vancouver, four years since he had become a citizen, and only a year since he had been elevated from a mere waiter to a restaurant keeper. Now he was a home owner!

No other Chinese lived on the street. The neighbours were older European immigrants, mostly Jewish, from Poland or Hungary, probably Holocaust survivors. Everyone there wanted to be Canadian, but nobody quite knew how; the children ate what their parents cooked—food from their countries of origin—and at home they spoke the language of their parents’ parents. Few of them spoke English. Ah Thloo did not go out to socialize with the neighbours, except to greet the elderly ones on either side of her, who always said, “Hello!” as she passed. They wouldn’t let her refuse their gifts of candies and cookies, and took every chance to pat Ah Wei’s and Ah May’s heads.

Only a few of the families had children, and all of them somehow learned to speak English, even without any native English speaker around. Ah May played with the girls who lived on the street while Ah Wei spent time with the neighbourhood boys he knew from school, but everyone was kept indoors after dusk.

All the parents kept a close eye on the children; they never went into one another’s houses. If Ah Wei or Ah May happened to be on a neighbour’s front stoop at mealtime, Ah Thloo would call out, “Ah We-iii, Ah Maa-ay, come home and eat.” Her children were expected to drop whatever they were doing and leave immediately. If they did not, she would just keep on calling. In that neighbourhood, everyone’s mother yelled out. Across the street, Muscha’s mother, an anxious Hungarian, would call out her daughter’s name every hour. They lived on the second floor and had a bird’s-eye view of the street, so Muscha just had to stand up to be seen and assure her mother she hadn’t been taken away.

The house on Bagg Street was a typical Montreal triplex, with a wooden staircase leading to a balcony on the second floor. One door off the balcony led to the second-storey apartment, while another opened to a flight of indoor stairs to the third-floor apartment. The Wongs lived on the ground floor, number 74 and leased the two upstairs apartments, mostly to Chinese families related to them in some way.

This house had rats as well, but the rodents stayed behind the walls and under the floorboards. Each evening, the family heard them scratching and scurrying from one end of the building to the other. A trapdoor in the floor of the bathroom opened into a crawl space under the house where Ah Dang, and later Ah Wei, laid rat traps baited with smelly Swiss cheese.

Ah Thloo and Ah May shared the front bedroom on one side of the main entrance hall. They slept in twin beds, facing a window that looked out to the front garden, where Ah Thloo planted vegetables. Ah Dang had a double bed in the adjoining room. There was no wall between the rooms, but a plastered crossbeam on the ceiling separated the spaces.

Ah Wei had his own room down the hall, off the living room. He had a view of the backyard—really just a dirt patch where not even dandelions grew. The three balconies faced onto the back. A sweet Jewish widow lived on the second floor of the house across from the Wongs. She used to throw down bags of candy and tried to engage Ah Thloo in conversation; Ah Thloo would eventually smile back, wave, and say, “Hello, howyu?”

The room across the hall from the front bedroom was Ah Thloo’s refuge. It stored all the precious things she had brought from China. It was also her workroom, where she could sew household items and clothes for herself and the children on a black Singer treadle machine.

One half of the room was lined with jars and tin boxes filled with traditional Chinese ingredients for health, long life, and vitality. Ah Thloo could have stocked an herbalist’s shop. There were gallon-sized Mason jars that held whole snakes pickled in brandy to fortify it for its vitalizing effects; she would ladle a small cup for the adults to sip at Chinese New Year. She also made rice wine, letting it ferment in the jars; it exuded a sour, bitter smell whenever the lid was opened. Again, the wine was drunk only on special occasions.

Enclosed in individual, large, airtight tin boxes were dried abalone, sea cucumber, seahorses, shrimp, sharks’ fins, scallops, seaweed, and sea grass. There were also dried mushrooms, lily stalks, wood ear fungus, herbs, dates, red goji berries, ginseng roots, hard round teacakes, and clusters of birds’ nests. Every day, she would make delicious soups using some of these ingredients. Others were reserved for special occasions. Yen waw gaang, birds’ nest soup, and nguey chee gaang, sharks’ fin soup, were favourite dishes eaten during New Year celebrations or birthdays.

The largest item in the room was a deep blue, metal travel trunk with brass bands and studs, which Ah Thloo had brought from Hong Kong. In it was a silk-covered comforter, stuffed with cotton, used only on very cold nights. It was fuchsia-pink on one side and turquoise on the other. The inside of the trunk, lined in blue silk, had an enduring fragrance from the bags of dried cinnamon sticks stored there.

Besides the traditional Chinese medicines, Ah Thloo had brought with her many of the traditional ways of preserving foods, one of which was to use the hot Montreal summer temperatures to cure food outdoors. Ah Dang made a special pressing rack, as well as a drying box, from wood lined with chicken wire and metal mesh to keep out flies. The door swung out and was secured with a wooden dowel and extra wire. The box was hung from a hook out on the back balcony.

After marinating strips of fatty pork belly in a mixture of gin, spices, sugar, and soy sauce, Ah Thloo strung the meat on a cotton string, using a large darning needle, and hung it in the box. This cured pork belly was called lap ngoke, and a small piece was all that was needed to add rich flavour to a dish. Sometimes she hung a whole marinated duck that had been split in half and pressed flat in the homemade rack. Lap ap, the cured duck, was a delicacy that made Ah Dang’s mouth water just thinking about it.

The European neighbours, especially the nice Jewish lady across the backyard, were very interested in the processes and were always asking Ah Thloo what was in the box. However, being wary, she would feign ignorance, shrug her shoulders, and smile blandly before retreating into the house.

Ah Thloo shopped for groceries every few days. She received a portion of Ah Dang’s weekly pay and managed the household from her own bank account. Although she had a refrigerator, all Chinese like to eat fresh foods, and shopping was a good excuse to get out of the house. She had a number of expandable string bags to carry the groceries. Until Ah May joined Ah Wei at Devonshire Elementary School, she accompanied Ah Thloo everywhere.

The Warshaw Grocery on St. Laurent, where Ah Thloo bought fruit, vegetables, and staples, was only two blocks from the house. Rice and Chinese vegetables like bok choy and gai lan could then be found only in Chinatown, where the family went every weekend.

Meat was selected from the Hungarian butcher shop a few doors down the street, where the clean smell of fresh sawdust was a counterpoint to the metallic odour of blood and the aromas of various spices. Ah Thloo might buy a piece of pork, cut from a leg displayed in the cooler. The meat was wrapped in a sheet of pink paper that was waxed on the inside and tied with a piece of string.

Processed meats were sold on the other side of the store. Tubes of round sausages were displayed behind the counter: long, short, thick, thin, fatty, dry, dark, light, all suspended from a railing hung from the ceiling. The salty, spicy, savoury smells from that side of the store always tantalized Ah May’s nose and tastebuds, but Ah Thloo, unfamiliar with the food, and being frugal, never bought any.

On the counters were displays of silk stockings (the kind that were held up by a garter belt) and fine hairnets in various colours. There were European confections, hard fruit candies with liquid centres, brightly coloured marzipan that was shaped into fruits or animals, and black liquorice drops.

The next stop was on Roy Street, where Waldman’s Fish Store and Liebovich Poultry were located. At the time, Waldman’s was just a cold warehouse filled with tanks of fish and shellfish such as lobsters, crabs, and prawns. Rows of trays on long tables held different varieties of fresh fish, covered in chipped ice. Some still twitched, their mouths kissing the air, seeking water. The floors ran with water and scales and occasionally blood and guts. Ah Thloo walked around the tables, poking eyes with a bare finger and lifting gills to see how fresh the fish were. The chosen fish was wrapped in newspaper.

If the fish were deemed unworthy, Ah Thloo took Ah May to Liebovich Poultry, referred to as Lie Giek Doy, Crippled Boy’s. This store was a small space filled with old, dirty metal cages, stuffed with chickens of all shapes, colours, ages, and sizes. There were ducks, pigeons, and turkeys as well. The birds’ body heat increased the temperature and enhanced the smell of the cramped, steamy room. The aroma was a mixture of chicken droppings, warm blood, and faintly fishy, faintly burnt feathers. Ah Thloo chose not to pay the extra charge for slaughtering, so with its wings trussed and feet tied together, the clucking chicken was stuffed into a string bag.

Loaded with the makings of a meal, mother and daughter walked home. Once Ah Dang was awake, Ah Thloo went about dispatching the chicken, always a noisy job, as the chicken inevitably squawked. However, she was efficient and sure-handed with her sharp, wooden-handled cleaver, chopping the head off in a single blow.

Whatever foods Ah Thloo could not make, she bought in Chinatown. Leong Jung, at 92 De La Gauchetière West, was a favourite grocery store. A gentle-spoken, white-haired man called Ah Lee Bak and his two sons owned it. Ah Thloo’s family was always welcomed with a cup of tea, poured from an oversized ceramic pot that was kept warm in a woven and lined tea cozy. The adults would exchange news and Chinatown gossip, while Ah May wandered through the aisles.

On the floor were rows of open burlap bags overflowing with exotic-smelling herbs and spices, square metal buckets of fresh tofu swimming in water, and rectangular wooden boxes of fresh garden vegetables. On shelves along the walls were stacked large tins of preserved vegetables, meats or fish, and sauces, as well as earthen jars filled with pungent salted black beans or thick molasses. In the back corner of the store, suspended on a black hook a foot long, in a frame that looked like an upended metal coffin, hung a whole roasted pig, smelling deliciously of a special blend of spices. As the day wore on, chunks would be cut from its carcass—the most desirable parts from its savoury ribs, topped with a coat of crispy, light, crackled skin. Ah Thloo splurged on a piece of the savoury pork from time to time. From the ceiling were hung cured meats and strings of the store’s famous homemade lap cheong, Chinese sausages. They had several varieties, including, duck, chicken, pork, and even one that was like a blood sausage. At home, Ah Thloo would cut a sausage into chunks and steam them on top of rice, the rich, sweet flavour and oil permeating the whole pot. Having arrived from China with recent memories of starvation, she at first enjoyed the fatty bits. Later, when she was more health conscious, she meticulously excavated each piece of hard white fat before cooking the meat.

Occasionally, she shopped downtown, travelling everywhere by bus, making use of Montreal’s efficient transit system. A single, inexpensive fare could take her all the way across the island, transferring from one bus to another. During the ride, Ah Thloo stayed vigilant, taking note of landmarks so she could remember the way home. She shopped mostly in the department stores on St. Catherine Street. Henry Morgan’s Store and Eaton’s, where they had a “no questions asked” refund policy, were her favourites.

Although Ah Thloo took some English lessons at the Chinese Presbyterian Church, she learned much of her English from watching television and late-night movies. Ah Dang bought a small, black-and-white television set with rabbit-ear antennae. During the day, Howdy Doody was on, and in the evenings, Ah Thloo and the two children watched shows such as Red Skelton, I Love Lucy, and Ed Sullivan. Ah Thloo learned to laugh with the televised laugh track. Late at night, she watched movies, accompanied by Ah Wei on the weekends, after Ah May had gone to bed. Ah Thloo never let on how much she actually understood of the English dialogue, preferring to speak to the children in Chinese.

• • •

The year 1955 was the start of a rewarding time for Ah Dang. In addition to the birth of his daughter, he was becoming successful in his relatively new career as a businessman. For work, he groomed himself carefully. His nails were neatly trimmed and clean. He brushed his hair and added a fragrant pomade to hold it in place. He wore formal dress socks, sometimes held up with garters, and kept his leather shoes polished to a hard shine. On the way to work, he always wore a fedora, which changed with the seasons—a felt one in the winter and straw in the summer. He always wore a suit, usually grey, with a white shirt and tie, sometimes a bow tie.

At the restaurant, Ah Dang replaced his suit jacket with a white cotton jacket, trimmed in maroon, to distinguish him from the waiters, who had jackets with green accents. He worked the till at the front of the restaurant and helped serve when required, but unless he mentioned it, few customers would have known he had a stake in the business.

Bagg Street house (boarded up after a fire). It has since been restored, 2004.

MAY Q. WONG, MONTREAL

Ah Dang with two of China Garden’s wait staff

(standing on right is Ah Chiang Hoo’s son).

UNKNOWN PHOTOGRAPHER, MONTREAL

The China Garden Café was located in the heart of Montreal’s shopping and business area and served Chinese-Canadian food to a varied clientele. Facing Dominion Square, it was a popular lunch spot for downtown office workers and shoppers. An ad published in the October 10, 1958, issue of the Canadian Jewish Review claimed the restaurant was “very convenient for ladies to meet their friends while shopping.” At night, clients came from surrounding establishments, such as the elegant Windsor Hotel, for a quick bite before catching a movie or for a more leisurely meal after a cabaret show. The restaurant could also be booked for parties.

The front part of the establishment was set up with large booths that could seat six people comfortably. On the wall in each booth was a small jukebox that played the latest North American hit songs. There was a dining room in the back, which could accommodate fifty to seventy people. The banquet menu had such items as war siew guy, stuffed crispy chicken. This was a rich and time-consuming dish to make, served on special occasions. It recreated a chicken, with a meat mixture that was stuffed into a whole chicken skin, then deep-fried. Ah Dang sometimes took one home for the family’s New Year’s dinner party. The restaurant also made the city’s best egg rolls and almond cookies.

The kitchen was on the ground floor at the back of the restaurant, where it opened onto a back alley and a private parking lot. The floors were raised on a wooden platform, and two gas ranges held four or five large woks each. A set of stairs led down to the basement, to the refrigerators, coolers, and preparation room. That was also where the office was located and where the resident mousers lived. The cool dimness of the underground room was a haven in the hot, humid summers.

The noise, from the waiters shouting orders, the whoosh of the gas flames, the clanging of metal spatulas flipping food in the metal woks, the hiss of wet fresh vegetables in hot oil, the bock ! of a sharp cleaver on wooden chopping blocks, and the shouts of cooks calling up plates of steaming hot food was a show in itself, but Montreal had more than enough entertainment.

The restaurant was a few doors from a strip club and a number of jazz bars. By the mid-1950s, the city was at the tail end of its heyday in the Golden Era of music as the place to be for the likes of Peggy Lee, Oscar Peterson, and Frank Sinatra. Montreal was becoming known as Sin City, its bars, brothels, and strip clubs run by gangsters. Open twenty-four hours a day, the China Garden was a favourite place for midnight snacks or late-night munchies between sets. Many of the clients were Americans who thought they were immune to Canadian laws, but Ah Dang proved them wrong. He worked the night shift and saw the worst of the offenders.

Ah Dang looked innocuous enough in his work clothes, but he was the enforcer in the restaurant. Every few weeks, he would get home late because someone had tried, unsuccessfully, to eat and run—literally, without paying for his meal. But Ah Dang would not let the culprit leave. He owned two items not normally packed by a restaurateur—a knuckle-duster and a leather sap, which he had learned to use effectively many years earlier.

Only five feet four inches tall, with arms akimbo, holding his sap, eyes bulging with indignation, he could look fierce, like a raging pit bull terrier. He worked too hard to let anyone take advantage of him by not paying. He would block the front door and tell his colleagues in the back to call the police. Sometimes there were scuffles and he was hurt, but never seriously; he still remembered how to protect himself.

The restaurant treated the local beat cops well, giving them free hot coffee and perhaps a meal or two; they always responded quickly. Ah Dang pressed charges when they arrived, which meant he had to go to small claims court the next morning, and this made for a long day. Although he was one of the owners, he never took an extra afternoon or evening off to make up for the court time. He did it all to be sure he got justice.

In the mornings, he came home around the time that most other fathers would be having breakfast or leaving for work. Ah May was always at the door to greet him. Quickly bussing his scruffy cheek, she would wrap her arms around his neck for a tight hug that was the high point of his day, and he would think, It’s all worth the effort—just for this!

• • •

Just as Ah Dang was helped by his adoptive father and Ah Ngay Gonge to settle in Canada, he in turn assisted others. Many people were given a hand to adjust; some were even related.

A number of single women stayed with the family before they got married. One young woman who maintained close ties was Ma Toy Yee, Ah Thloo’s eldest sister’s daughter. Ah Yee came to Montreal from Hong Kong in 1960, as a bride to Wong Chuck Min (distantly related to Ah Dang), who worked as a cook at China Garden. At twenty-two, Ah Yee was vivacious, glamorous, and great fun, and Ah May, then only five, thought she was her big sister.

The family accompanied the newlyweds on their honeymoon to Niagara Falls, because Ah Dang had to interpret for them; neither of them spoke any English at the time. When each of their first three children was born, it was Ah Dang who took his niece to the hospital and awaited the birth, and it was Ah Thloo who taught her niece how to bathe, change, and feed her first baby.

Back, left to right: Ah Thloo, Ah Min, and Ah Wei.

Front, left to right: Anna, Ah Yee with Helen, and Truman, circa 1960s.

MAY Q. WONG, MONTREAL

By the time their fourth and last child was born, Ah Min was able to accompany his wife on his own. At first the couple shared an apartment with Ah Min’s elder brother, but the growing family needed more room, and they moved to the third-floor apartment on Bagg Street as soon as it was available. Ah Thloo and Ah Dang were surrogate grandparents for the children, a wellspring of wisdom, toys, and adventures.

Although Ah Dang had moved away from Chinatown, he never forgot those who had stayed behind. He and Ah Thloo regularly took Ah Wei and Ah May to visit different Ah Baks, Elder Uncles, who may or may not have been actually related.

Mostly, they lived in dark rooming houses above the stores that lined Chinatown, with rickety, dark stairways leading to rooms resembling rabbit warrens, but with less air. The men shared cooking, cleaning, and bathroom facilities. Each had a small personal space, enough for a single bed, a chair, a dresser, a small table, and shelves to hold non-perishable foods, a book or two, and perhaps some photographs. The rooms weren’t always totally contained; sometimes there were only half-walls on either side, with a cloth curtain drawn across the front of the cubicle for privacy. The men could hear their neighbours snoring, coughing, talking to visitors, snapping a newspaper, or listening to the radio. The place smelled of stale sweat, unwashed bodies, and cigarette smoke. Always, they lived alone. Their wives and families, if they had any, were in China.

A part of Chinese etiquette was to bring siu thlem, a small gift, whenever one visited another person’s home. Usually, it was oranges. When the Wong family visited the Ah Baks, they would bring a little more, perhaps a piece of char sui, Chinese barbequed pork, or half a roast chicken, for the men’s meals that evening. Ah Dang also brought them packages of tobacco and cigarette paper.

The men made a fuss over the children, marvelling at how big they were and telling them to be studious, and to hiang wa, listen to being told, be obedient. They missed being able to tell their own children these universal lessons.

One very old Ah Bak lived in a laundry on St. Hubert Street, close to the city’s downtown area. Ah Dang always brought extra gifts whenever the family went to visit, which was about every three months. In a large paper bag, Ah May would see her father pack a bottle of whisky, a dozen oranges, a string of Chinese sausages, a large tin of tobacco, and a variety of cooked meats from Chinatown that would have fed their own family for a week. It wasn’t until decades later that she figured out he was the Ah Ngay Gonge who had helped her father come to Montreal.

Nor did Ah Thloo or Ah Dang forget the families they had left behind in China. Ah Dang sent money to Ah Lai and his mother. Ah Thloo’s Christian instruction taught her that forgiveness was right, and she had forgiven her mother, her brother, and his wife for the time during the war with Japan, when they had turned their backs on her. She understood that they had made a mistake in judgment then—desperate times had made them do it. She taught her children filial duty by supporting her family. Faithfully, every month, Ah Thloo sent a portion of the money she had set aside from Ah Dang’s weekly pay to purchase a bank draft from the Nanyang Commercial Bank in Hong Kong, with instructions for the dispersal of funds to her parents and other relatives. While the amounts were diminished after the deaths of her parents, she sent money to China each spring for Qing Ming, Grave Sweeping Day.

Ah Thloo did not adhere to the traditional Chinese attitudes toward boys and girls in families. She had always considered her younger brother as part of her family, just as her married daughter was still counted as her daughter. Blood was a stronger tie than tradition. Blood transcended lapses in judgment.

• • •

In August 1961, Ah Lai married her high school sweetheart, Guan Haw One, following the new conventions of the People’s Republic of China. Wearing similarly plain outfits consisting of a new, homemade, button-down blouse for her and shirt for him, dark pants, and sturdy leather shoes, the couple was joined in matrimony before a government registrar. Again, following the new custom of equality between the sexes and recognizing that women were no longer chattels, Ah Lai signed the certificate using her own family name—Wong Lai Quen. It was not until a month later, after she had completed her studies, that the couple could travel back to their home villages to celebrate with Ah Ngange and her husband’s mother. At their respective homes, the couple made obeisance at the family shrines, and feasts were held, to which all the neighbours were invited. Some old conventions were hard to break. Ah Lai’s and Ah One’s first daughter was born on April 20, 1963.

In Montreal, on April 21, 1963, Ah Thloo and her two younger children were baptized by Reverend Paul Chan and officially inducted into the Chinese Presbyterian Church. “Isn’t it funny, we used to worship inanimate things, like rocks and the tombs of ancestors!” said Ah Thloo. Although she never lost her fascination with rocks and natural things, she no longer believed they harboured spirits or represented gods. Instead, she saw God’s hand in their creation. And while she continued to send money to China for Ching Ming, to keep the grave markers from being swallowed by the surrounding vegetation, she did so as a gesture of respect for her elders, rather than as ancestor worship. After her baptism, she no longer bought and burned incense in the house. “The Church teaches us about Jesus, who died but now lives again. He is a living God. I didn’t know any better—no wonder I was so miserable before I converted.” Her faith helped her learn to forgive her parents, but she was still learning how to deal with her husband.

Ah Dang was baptized into the United Church of Canada, but on March 28, 1965, he transferred to the congregation of the Chinese Presbyterian Church. He was not a particularly religious man; he hardly ever attended church services. Nevertheless, the church became the family’s spiritual and cultural centre. The children attended Chinese School on weekends and church services on Sundays. Between 1965 and 1986, Ah Thloo worked with, and later supervised, the ladies of the Women’s Missionary Society, cooking for the annual tea and bazaar fundraiser.

In August 1963, Ah Dang bought 12014 St. Evariste Street, a two-storey duplex with an unfinished basement and underground garage, for twenty-two thousand dollars, half down. The remainder was mortgaged at 7.5 per cent till June 1, 1965. He had decided it was time to move to a newer part of town, but he hadn’t consulted much with Ah Thloo.

The new duplex, in the French-Canadian suburb of Cartierville, was just one example of Ah Dang’s lack of communication. He had chosen it because of the fresh air and sunshine in the open fields behind the house, and because moving to the suburbs was a mark of upward mobility. One of their fellow church members and his family lived across the street. However, the liveable space in the duplex was smaller than the house on Bagg Street, and it was far away from the shopping and cultural areas frequented by Ah Thloo. As always, she adjusted.

Before Ah Thloo came to Canada, she had thought her time here would be short. Her intention had been to deliver Ah Wei to his father and return to China when the boy became more independent. However, her plans were unexpectedly changed by the birth of their last child. Now that she was to be in the country for a bit longer, she hoped Ah Dang would discuss matters with her before making major decisions, but hope needs to be translated into communication, understanding, acquiescence, and action. All of these take practice. Their wedding night had sown a seed of ill will, and Ah Dang’s two subsequent short visits, limited as they were by the threats of war in China and the fear of expulsion from Canada, had not allowed the couple the opportunity to learn how to talk with, or listen to, each other, or to work together as a unit. Certainly, Canada’s exclusionary laws, which did not allow Ah Thloo to join her husband, had not helped their situation, forcing them to become independent of each other and to be self-sufficient. Misunderstanding and recrimination were too firmly etched in their relationship to be changed in their middle years.

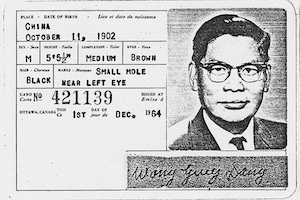

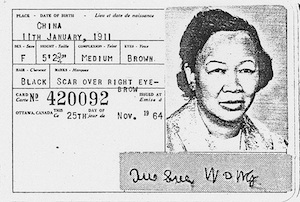

Guey Dang Wong’s and Tue Sue Wong’s citizenship certificates.