Applicant arrived in Canada 11th Oct., 1921 on the “SS” [] , Port of Vancouver, BC. From Port of Entry he remained in Vancouver for eight years, then proceeded to Montreal, Que. . . . He made three trips to China for a total of three years and two months out of Canada, the last trip being from March 1947 to June 1948 and on his first trip he married in China . . . Chinese Immigration Certificate checked and found in order. Sponsors appear to be of good character and are not known or suspected of having any subversive tendencies toward the State.

NINE

Father Regroups

AH DANG: MONTREAL, 1949–53

During the voyage back to Canada, the photo of his son kept Ah Dang’s spirits buoyed, despite the emptiness he was feeling. This separation will be harder than the other two because I now have a son!

When his first child was born, she had been an unexpected surprise and delight. She could make him laugh out loud just by curling her little hands around his pinkie; he had created a family of his own. Now he had a son. He had never known he could feel this way about a child who still could not talk or walk; he felt invincible!

Thinking about his boy, he could almost, but not quite, forget his bafflement regarding his daughter. On this last visit, when she was certainly old enough to talk sensibly, he had not understood her reaction to him. He had tried hard to let her get to know him, but it was almost as if she was afraid of him. What was there to be afraid of? he wondered. While he was in the hamlet, he had never laid a hand on her in anger nor ever raised his voice.

He had watched her from a distance as she interacted with other adults. With them, she was chatty, easygoing, even happy, and he especially noticed how affectionately she treated her Ah Ngange. Yet whenever he spoke to her, she was reluctant to talk to him and tended to respond in single words, even after a whole year of living in the same house. He was proud of her though; she was always first or second in school. She was a smart one.

He thought about Ah Thloo. He did not know what he had done to deserve such a difficult wife. He had long ago learned that beating her did not change her—it only made her more ngang giang, stiff-necked and stubborn. He had given it up. He recognized and admired her gumption.

He himself had learned to fight when he first came to Canada. The British Columbia fishing and logging camps, where he had worked as a cook, attracted rough, tough guey law, devil or ghost men, hooligans. Living together in close quarters and away from civilization made them feel like prisoners, and they needed a diversion to vent their feelings. A Chink was an easy target. He was a Chink, sometimes the only one in the camp.

The first time he was picked on and beaten, he was afraid to fight back and had to stay in bed for two days, losing wages, before he could resume work. He vowed it would never happen again. The next time he was in town on leave, he bought a knuckle-duster and a leather sap, both of which he learned to use effectively, and he never left home without his protection. The hooligans got as good as they gave. Soon, Ah Dang had a reputation for being tough, earning him some grudging respect among the whites.

Ah Thloo was like that, much like Scarlett O’Hara in his favourite movie, Gone with the Wind. He had gone to the theatre to watch it at least thirteen times. Scarlett was feisty too: single-minded in getting what she wanted and not bending to anyone’s will. Fearless. His little wife had saved the village from bandit raids and the Japanese, if the stories he had heard from the neighbours were true. He believed them. He would believe anything they said about Ah Thloo. She would never boast about it to him, but he knew she was capable. That was why he wanted to keep her. He would never abandon her for another because he knew they were so much alike. He had been right to choose her.

But she could make him so angry! It took just a few well-chosen words, and his blood boiled so much that he felt his eyes popping out of his head like those fancy goldfish sold in the market. She had learned from that poisoned-tongued viper, his mother, after all. But I don’t want to think about my mother, and he shook his head to get her image out of his mind.

On this last trip to China, he had stayed away as long as he dared, fifteen months—by far the longest time he had been out of Canada. He entered his adopted country at the port of Sarnia, Ontario, on June 6, 1948. For the first time, he was not detained and humiliated by immigration officials upon landing on the shores of his chosen home, nor was he required to show his head tax receipt. Rather than being herded off, he disembarked at his leisure with the other passengers and went on his way, just like a white person. Just like a human being. It felt good!

• • •

More than ever before, Ah Dang was eager to have his family join him in Canada. He had not been able to watch his daughter grow up, and now she was a stranger to him; he did not want that to happen with his son. For a time, he kept trying to apply for permission from the Chinese government for his children to join him, but in the spring of 1949, he decided to work at getting his Canadian citizenship. He had lived in the country for twenty-five years, thus establishing himself as a resident.

The process entailed eight steps and took almost two years. The first step was for Ah Dang to submit a Declaration of Intention. The purpose of this was to show how and when he had arrived in Canada, list his trips back and forth to China, indicate identifying marks on his person, and provide information about his family. His signature on the form indicated his willingness to renounce any allegiance to any foreign sovereign or state. On May 25, 1949, the form was notarized by a justice of the peace. The declaration had to be accompanied by two other corroborating documents: a memo from a commissioner of the Immigration Branch, to confirm Ah Dang’s original date and port of entry into Canada, which took a month to be processed; and a confidential report by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which took two months. The RCMP conducted an investigation and interviews with Ah Dang, as well as with two “prominent British subjects” who vouched for the applicant and confirmed he was recognized as “being of good character.”

Not unlike banns for a marriage in some churches, the Canadian Citizenship Act required the declaration to be posted at the courthouse in a public and “conspicuous place” for three months. This was done starting August 25, 1949.

However, it was not until a year later, on August 8, 1950, that a Petition for Citizenship, in which the applicant “humbly prays” that a Certificate of Citizenship be issued to him and to his minor children, was granted by Judge J.G. Magnan. Ten days later, the petition, attesting to the fact that Ah Dang was “a fit and proper person to be naturalized,” was forwarded to the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration for a final decision. Approval by the Registrar of Canadian Citizenship was granted on November 26, 1950. On January 26, 1951, Ah Dang finally became a Canadian citizen, swearing true allegiance to His Majesty King George the Sixth.

• • •

By the 1950s, Montreal was bustling, becoming the country’s financial centre. Quebec was attracting workers to its growing industrial sector. In the latter half of the decade many in the Chinese community were bringing their wives and children, so the province’s Chinese population rose from 1,904 to 4,794, most of it concentrated in Montreal.

When Ah Dang was in China, he had listened to the locals and the townsfolk discussing the civil war. While he was careful about what he said, to whom he said it, and within whose hearing he spoke, he gained enough information to make a choice. He had been a strong supporter of Dr. Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang Party, and although he had not joined any political associations in the Chinatowns of Canada, he had purchased bonds and donated to the local KMT chapter. But he was outraged when, soon after the Japanese surrender in 1945, General Jiang had used Japanese soldiers to fight the Communists. That action had made him stop donating to the KMT Party.

When Ah Dang had last been in China, he had seen the widespread corruption and carpet-bagging greediness of KMT officials. In seeking a solution to his children’s immigration situation, he had given the suggested bribes, but still, nothing had happened. The KMT’s economic policies, intended to curb runaway inflation, were disastrous. In 1937, a hundred yuan could purchase two oxen; by 1949, it could buy only a sheet of paper. In 1948, when the KMT attempted a currency reform measure to create the “gold yuan,” prices rose eighty-five thousand times within a six-month period. Ah Dang held little hope for a continuing government under the KMT.

He could have stayed neutral, for he had chosen Canada as his country, but he had to safeguard his family in China, in case, for whatever unthinkable reason, they could never join him. He decided to learn more about the Communists for himself, so, on his last trip, he had attended some of Ah Thloo’s meetings and work parties.

Ah Thloo had told him how different the Communists were from any other soldiers who had come through the countryside, hardworking and helpful. Ah Thloo introduced him to some of the Communist soldiers. As they did not wear uniforms, but the same clothes as the locals, it was at first hard to distinguish them. However, as Ah Dang watched, he noticed an aura of authority about them, indicating training and discipline. They looked genuine to him.

Having been a victim of the peasant feudal system, he could see the positive intent of, and benefits being produced by, the land reform program. By sharing tools, seed, and labour, his family and neighbours also shared in the diversity of the harvests. Perhaps China had a future with the Chinese Communist Party in government. He made his first donation to the CCP before he left China.

Back in Canada, Ah Dang followed the progress of the Communist People’s Liberation Army in the civil war. Significant battles continued in key locations, including Beijing, Nanjing, the KMT capital, and Chengdu, to which Jiang retreated after resigning as president of China on January 21, 1949. On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China. On December 10, 1949, Jiang left China for Taiwan.

Following the formation of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese newspapers reported that many well-to-do citizens were fleeing to Hong Kong and Macau, where living conditions were far from ideal. Relatives in foreign countries feared that China’s new collectivist principles meant that much-needed remittances would be confiscated, but Ah Dang did not have to worry on that account. He had left Ah Thloo the bulk of his savings, and he knew she would keep the money safe and spend it wisely. But he needed her and their children here. Armed with his new citizenship rights, he set about bringing his family to Canada.

• • •

AH THLOO: CHINA, 1949–1952

The war is over! Have you heard—the war is over?! The joyous cries were almost as ubiquitous as the greeting “Have you eaten rice yet?” Especially in Tiananmen Square.

Built during the Ming Dynasty, Tiananmen, the Gate of Heavenly Peace, is where imperial edicts were issued or announcements of great import made. On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong stood on the viewing balcony of the gate to hoist up the new flag of China—five gold stars on a sea of red—and declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Below, on the square, thousands of people cheered, waving banners, lanterns, and scarves. Beijing was once again the capital.

Earlier that day, Mao was appointed chairman of both the Central People’s Government and the People’s Revolutionary Military Committee. Zhou Enlai was appointed premier of the Central People’s Government Council and minister of foreign affairs.

In most parts of the country, a collective sigh was exhaled; outright battles would now stop. However, pockets of resistance by KMT forces and their sympathizers would continue to be a problem for the next few years.

From 1949 to 1952, the Central People’s Government concentrated on rehabilitating the national economy. The state seized control of everything. Private businesses were condemned, and their owners, if they had not managed to flee the country, were in jeopardy. The state took over customs, banks, mines, factories, and transportation systems. Inflation was brought under control. Supplies of basic necessities, such as food, cotton, cloth, coal, and salt, and staples such as grain and seed were all centralized. Transportation systems, including railways, shipping lines, and roads, were revived.

More importantly in the countryside, the government took over all the land and private property. Landlords, considered corrupt and a bane to peasants, were stripped of their wealth and persecuted. Although Ah Thloo and her parents had owned land, they had worked it and not leased it to others, so they were not considered landlords.

In fact, Ah Thloo worked on the land redistribution project, helping to ensure that landless tenants and the poorest peasants gained the most while absentee landlords lost the most. Groups of poor peasants gathered together to celebrate the burning of their rental bills, which had been charged in produce and disguised as taxes and duties. By 1952, more than three hundred million peasants had received forty million hectares of land and were exempted from rents of more than thirty-five billion kilograms of grain.

It is not now known how much land Ah Thloo and her family received in the redistribution, but it was soon irrelevant. By then, Ah Lai had returned to school, this time to a boarding school. Soon afterwards, her family experienced a drastic shift.

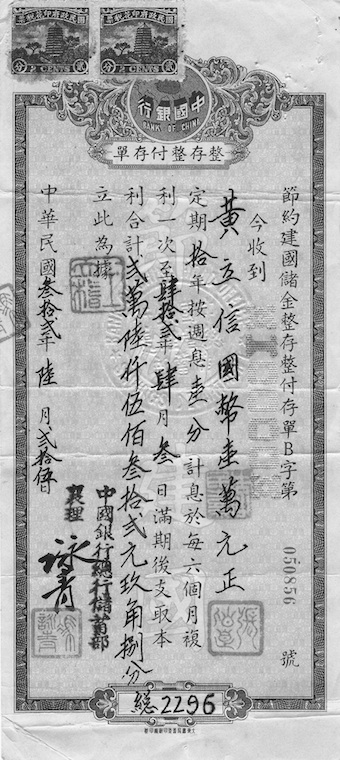

Chinese war bond.