And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people.

For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and saying,

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

TEN

First Christmas

AH THLOO: ALASKA, DECEMBER 24, 1954

The airplane meal was distributed not long after the flight took off from Alaska. Ah Thloo did not recognize any of the food: there was some kind of dry white meat, a mound of white, mushy starch, some green peas, and a spoonful of red sauce, and covering everything was a grey-brown sauce. No rice. She tasted a bit of everything and found it was “edible—but only just,” as Ah Tew May used to say about all of Ah Thloo’s cooking. It was very bland, except for the red sauce, which she anticipated might be spicy but turned out to be sweet.

After the meal, the stewardesses gave everyone a small gift wrapped in bright, festive paper. Ah Wei got a toy, and Ah Thloo thought, What a nice way to welcome us to Canada!

• • •

AH THLOO: CHINA AND HONG KONG, 1953–1954

It took some time for Ah Thloo to decide if she wanted to uproot herself and her family to start life anew in an alien environment. In China, she had established an independent life—quite an accomplishment for a woman. She had had to make life-and-death decisions; her family had remained intact and had survived famine, bandits, war, and revolution through her efforts. More recently, she was engaged in important work to improve the economic life of the community. People sought her opinions and her help; she had become a leader.

By 1953, she and Ah Dang had been married for almost a quarter-century, but they had spent less than five years together, much of it in conflict. Who would look forward to more of the same? However, she had to admit that he had tried harder than any other Gim San law she knew of to send money.

It was something in the first letter she received after the revolution that clinched her decision. Ah Dang told her he had received his citizenship, and could now legally apply for her and the children to go to Canada. He had told her he could not apply for his mother: Canada would not let her into the country. He also wrote, “Ah Thloo, you are my second life. I cannot go on without you.” Finally, he had written her some hiem wa, sweet words. Perhaps he had changed.

She showed the letter to her daughter. Ah Lai had known for a long time of her father’s wish for the family to join him in Canada. With his citizenship it was now possible and the declaration of love was making it more of a reality.

Ah Thloo felt it would be cruel to tell Ah Ngange (as she called her mother-in-law, now) that she had not been invited, but the older woman refused to go anyway, claiming, “I am seventy years old, too old to survive the long trip. I wouldn’t last a day living in the country of faan guey law, foreign devils! I’m staying here. I’ll die in my own home.”

She had never spoken out against her son’s wishes and his right to have his children join him in Canada. Ah Thloo knew Ah Ngange loved the children, and that the feelings were mutual. From a distance, she had watched them together; the older woman’s voice became affectionate and she actually smiled when she was with them. As a child, Ah Lai had always run to Ah Ngange first when she came in from playing outdoors, and it was no different now. When she came home from boarding school or if she was upset, she sought solace from Ah Ngange first, then perhaps practical advice from Ah Thloo. Ah Wei, ever watchful of his sister’s actions, followed suit.

While Ah Thloo had always envied their relationship, she was grateful for her mother-in-law’s help in raising the children, and she was surprised but relieved when the older woman so adamantly refused to join them in going to Canada. In her own heart, Ah Thloo nursed a hope that perhaps away from Ah Ngange, she and the children could seal the gap between them.

They were all about to leave the village for the city of Guangzhou when Ah Lai went to her mother in tears. Ah Thloo thought she was feeling sad at having to leave Ah Ngange; she knew they were very close, but she didn’t know how devoted until then.

“Ma-ma, please do not be angry at me for what I’m about to say.”

“Ah Nui, what is it? You can tell me anything.”

“I don’t want to go to Canada.”

“Don’t be afraid. I know things will be different. But I promise, we’ll be together. I’ll spend more time with you.”

“It’s not that.”

“What’s the issue, then? You’re still too young. How can I leave you behind?”

“Ma-ma, I’m eighteen years old. At this age you were married to Ah Yea.”

“We are not talking about me. Times were different then.”

“You know I want to marry Ah Haw One.”

“Ah Yea should choose a husband for you!”

“I don’t believe in that old-fashioned practice of blind marriage, and neither do you!”

This was true enough. Having been a victim of such a union, Ah Thloo had been actively promoting women’s rights since the revolution, but she wasn’t going to let her daughter catch her with that argument. However, she had met Ah Haw One many times and tacitly approved of her daughter’s choice. She had worked with his mother on some of her committees, so she knew something of his background. His father was also a sojourner, to Southeast Asia.

“In Canada, life will be better. There’re no famines or droughts, no food shortages.”

“How can life be better in a country that hates us? It has kept our family apart! In the four years since Gai Fong, our own lives have improved here. The murderous Japanese have been defeated. The warlords who roamed the country raping the land have been executed. Landlords no longer hold all the wealth in their corrupt hands. The people, peasants like us who work the land, now have rights and power.”

It was a long speech, like something the girl had practised for a school recital. It reminded Ah Thloo of the long passages she had had to memorize during her few years at school. Inwardly, she agreed with everything her daughter had said and was proud that the girl had learned her history so well.

Ah Lai continued, her words tumbling out faster and faster, like hot pebbles burning her tongue. “I’ve just been accepted into college. I’ve worked to stay in first or second place at school! I can get a good education here. I want to help rebuild my country. This isn’t the right time for me to leave! I can’t even speak the language in Canada, and I’ll be too old to start school all over again. My little brother will have his chance. You must go for his sake.”

It was obvious her daughter had thought hard about this, and Ah Thloo could not find any fault in her reasoning. She was right: for four-year-old Ah Wei, everything was still new and no matter where he lived, he would adapt. He would also grow up living with his father, important for a boy.

Finally, Ah Lai said, “Also, there is Ah Ngange. It will break her heart to have her grandson taken away from her. I think she still needs me.” Ah Thloo understood that her daughter had chosen Ah Ngange over her. It must have been as hard to say as it was to hear, but the decision had been made, and was to have long-term consequences.

After their discussion, Ah Thloo cried herself to sleep every night. Ah Lai was away at school. When she came home on the weekends, Ah Thloo acted as if everything was back to normal and never again brought up the subject of going to Canada.

Ah Thloo made plans to go to Guangzhou, where the Chinese emigration offices were located. She did not know how long it would take for the government to grant her and her son leave to emigrate, but Ah Dang had told her to anticipate a long wait, both in various offices, where she had to be interviewed in person, and between meetings, while decisions were being pondered.

Ah Dang had sent money to buy goods in the city, so Ah Thloo packed only what she could carry in one suitcase. There wasn’t much from their lives in their home village that would be useful in Canada anyway. She took a change of clothing, the least faded and tattered of their belongings; they had been patched so often that even she couldn’t tell what colour the original fabric had been.

She left all of the bed coverings she had so carefully embroidered for her wedding. Although they had been cleaned and stored away with mothballs, after almost a quarter-century, they too had inevitable stains and holes. Besides, they were too bulky to carry. Nothing from the kitchen either, except for their ivory chopsticks. Ah Ngange would need everything else.

Ah Thloo had let the neighbours know of their intention to leave, if not the exact date. Every family had had members leave, so it was not an unusual event. Still, everyone loved sweet little Ah Wei, and Ah Thloo’s contributions to the county were well recognized; they would both be missed. Each neighbour family came to the house to say goodbye with gifts—folded paper packages of loose tea or herbs, trinkets for her son—and letters to their overseas relatives to be sent from Hong Kong.

Some of them, like her neighbour, Ah Chiang Hoo, would themselves be going to Montreal, so they would meet again there. Still, it was hard to say goodbye. Ah Thloo nodded when the families told her they would look after Ah Ngange, although she thought it more likely the old woman would be looking after them. She wasn’t the person for whom Ah Thloo’s heart was as heavy as a bushel of damp grain.

As for her own parents, Ah Thloo did not feel the need to bid them a final farewell. She had left their household when she married, and though she had visited them annually, she still felt ostracized by them. They had made that clear during the worst of the war with Japan, when they had denied Ah Thloo and her family food. Time enough to inform them of her move after she had settled in Canada.

On the evening before they left, Ah Thloo walked through the tiny hamlet, trying to memorize everything about the place she had called home for the past twenty-four years. As she strolled, the stand of tall houses already seemed to have turned their backs on her. All she could see were flickering yellow lights from kerosene lamps and kitchen cooking hearths, as the women, including Ah Ngange, prepared their evening meals. The smells of burning grass, firewood, and coal mixed with those of hot peanut oil, browning garlic, and soy sauce. The sudden crackle of oil indicated the addition of wet greens to a hot wok. She caught the pungent smell of haam nguey, dried salted fish, as it was steamed over rice, from several homes. From the bamboo garden, she heard the rustling of leaves and could imagine the bamboo swaying in unison as a breeze blew through it.

The children, including Ah Wei, were playing outside, climbing trees and chasing each other, or the chickens, dogs, and piglets, around the yard. Ah Thloo had not told the youngster anything about the trip. She did not want to upset him with the knowledge of parting from his beloved sister or grandmother. He played innocently, giggling, lighthearted, and happy among his friends.

The men sat on low stools outside their doors in the laneway, gong goo-doy, telling stories, or napping. Later, they would bring out their tea and water pipes and continue their men’s gossip. After dinner, Ah Ngange helped Ah Wei get ready for bed; she would stay with him through the night. Ah Thloo washed the dishes and tidied up. Then she brought a three-legged wooden stool out to have a last chat with the moin how, front door, neighbour. There was nothing much more to say about the upcoming journey; they just talked about this and that to pass the evening. When Ah Thloo finally retired, she tossed and turned for a long time before falling into a restless sleep.

The three family members left home at dawn the next morning, quietly and without much fuss. They would need the time to make their connections. Ah Ngange insisted that she piggyback her grandson all the way to Hien Gong Huy, the market village, where the next part of the journey would take place. He did not protest; he loved to ride on her back whenever he had the chance. She did not need to use the via aie, baby sling, to carry him. “That’s for babies!” he had protested. “I’m big now!” He hung on tightly, wrapping his arms around her neck and his legs all the way around. Her torso was so skinny that he could hook his feet together without crushing her.

It was about eight kilometres to Hien Gong Huy, and Ah Wei slept for most of the journey. Ah Ngange was hardly out of breath—she had walked everywhere all her life and was used to carrying burdens on her back for long distances. She did not consider her grandson to be a burden.

Ah Thloo walked behind her along the dirt path between the rice fields, carrying the suitcase. As they passed through the fields, the sharp smell of recently spread night soil followed them all the way.

A regularly scheduled bus stopped in the market village to take people to the riverside city of Thlam Fow, where Ah Thloo and her son would board the boat taking them up the river to Guangzhou. Ah Ngange would go back home from there, and when she stopped walking to let Ah Wei down, he started to cry, howling loudly. His little arms, wrapped around her neck, now refused to let go.

“Don’t cry, my Gowdoy; you are big now. Your Ah Yea won’t like to see you cry. I’ll see you soon.”

Wrenching his hands apart, Ah Ngange turned him to face her and hugged him fiercely. It was the first time Ah Thloo had seen her mother-in-law cry. Tears seeped out of the corners of her eyes, but before she released the boy, she wiped them from her face, leaving sooty streaks. Straightening up, she opened Ah Thloo’s hand and deliberately transferred the small boy’s struggling fingers to his mother’s strong grasp. Without another word, she turned and headed home.

Ah Thloo felt her own hot tears stream down her cheeks as she attempted to quell the heartache her son was sharing so loudly; it was hard not to empathize with the old woman. Also, she was feeling the anxiety of what was to come.

• • •

In Guangzhou, they rented a room in a large house, recommended to them by a neighbour from their hamlet. It was a surprisingly modern home, and Ah Thloo was especially impressed by the conveniences of indoor plumbing. Rather than having to draw water from a well, it came from a tap inside the house. She had used one of these before when she and Ah Dang had come to the city a few years earlier.

Here, though, she saw something truly amazing: an indoor toilet. It consisted of a raised ceramic area on the floor with a hole over which a person squatted. Water from a bucket was ladled over it to flush, and Ah Thloo assumed the waste was collected wherever the drain ended. The landlady just laughed when Ah Thloo asked about it and assured her the drains emptied into the harbour. Imagine a place that no longer required its night soil as fertilizer! She was starting to experience a new world.

The landlady was known simply as Ah Law Ah Hoo, Old Granny. She had jat giek, bound feet. She was a well-to-do widow whose only son and daughter-in-law had died recently, leaving a daughter whom Old Granny was raising on her own. They were a loving pair, each taking care of the other. Ah Thloo was reminded, with heartbreaking clarity, of her own dear Ah Ngange and herself as a young girl.

They quickly all got to know one another and started to share meals. The girl, Ah Ngan Jean, was a few years younger than Ah Lai, and the two girls met when Ah Thloo sent her daughter tickets to come to Guangzhou for a holiday. Ah Lai had just graduated from high school and the trip was to celebrate her hard work and success. Ah Thloo hoped that she and her daughter would use the time for a reconciliation.

Ah Lai stayed for a month; it was her first visit to the city. They had to be careful with money but managed to sample the dim sum at a different restaurant once a week. They ate simply, but Ah Thloo treated the children to an occasional fresh fish, pork, and haam toy, pickled vegetables.

The three spent their days exploring the city. At home and in the market town, travellers’ choices in transportation were mostly based on human power—feet or occasionally bicycles. In Guangzhou as well, the roads had more bicycles than motor vehicles, but city buses went everywhere. For a few tien, coins, they could ride the bus for miles, gazing out in amazement at the seemingly endless metropolis, totally under cover, sheltered from the weather. Passing the residential areas inland from Whampoa Harbour, they caught glimpses of European architectural influences, in the Western-style mansions of former shipping barons.

It was easy to spend hours at the markets, where they shopped for food every day. The markets were much larger than any they had been to at home. There was so much to see and do—every sense was bombarded by variety and novelty. Ah Wei was easily bored and tired, so mother and daughter took turns to piggyback him during their walks. Ah Thloo saw that Ah Wei loved having his big sister with him and that they doted on each other.

The place they liked best was a park just a few blocks from the house. It was built around a tranquil lake, dotted with fragrant gardens, tall pagodas, and delicately arched bridges. It was very peaceful and they spent a lot of time there. Sometimes they included Ah Ngan Jean and her grandmother on their outings.

One day, Ah Thloo took her daughter shopping to buy a special graduation present with money sent by Ah Dang for this express purpose. They chose a short-sleeved, A-line dress, in a multicoloured flower print. The next day, with her hair tied in ribbons, wearing the dress, embroidered ankle socks, and a new pair of black Mary Jane shoes, Ah Lai had her picture taken. Knowing the photo was for her father, she stood tall and straight, smiled shyly, and looked thoroughly modern. Over the month, Ah Thloo felt she and her daughter had come to an understanding, and they had a warm, though weepy, leave-taking.

While Ah Thloo waited another few months for travel documents, she filled the time by getting to know Ah Ngan Jean. She had developed a soft spot in her heart for the youngster. Ah Ngan Jean was a serious girl, content with life. She was also smart, with a bright future ahead of her, if given the opportunity of an education. Having spent time with Ah Lai, the younger girl was also keen on the idea of schooling.

Old Granny was a traditionalist and had not considered it necessary for the girl to be educated. After meeting Ah Lai, however, she saw that schooling had not spoiled the girl’s manners. Ah Thloo couldn’t know how long Old Granny would live, but when she died, Ah Ngan Jean would be left on her own, without anyone to guide or sponsor her. Ah Thloo felt she had to do something. She sought agreement from her husband to contribute to Ah Ngan Jean’s education, which helped pursuade the older woman to allow her granddaughter to go to school. Through a pledge, Ah Thloo became the girl’s kai ma, godmother.

Again, when the time came for their next move, Ah Thloo did not tell her daughter beforehand that they were leaving for Hong Kong, in the British Territories. Ah Lai had to learn from Ah Ngan Jean that her mother and little brother had left the country. No one knew when any of them would ever see one another again.

• • •

Friends in Guangzhou arranged accommodations for Ah Thloo and Ah Wei in Hong Kong, where they had one bed in a small room in a large, crowded apartment building. The cooking area and washing facilities were at the end of a hall, which they shared with families on the same floor. Everything was so cramped that only one person could cook at a time. Mealtimes were hectic, as all the women jostled for space, screeching at one another if they didn’t get their way. Ah Thloo preferred to wait till everyone was finished. It was easier, even if they had to eat much later.

Ah Thloo, Ah Wei, and goddaughter, Ah Ngan Jean, 1952.

UNKNOWN PHOTOGRAPHY STUDIO, CHINA

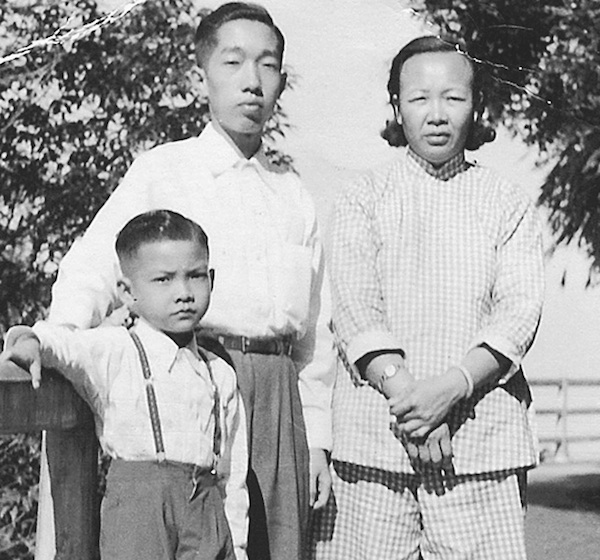

Ah Thloo, Ah Sang, and Ah Wei, 1953.

UNKNOWN PHOTOGRAPHER, HONG KONG

They were in Hong Kong for almost a year and a half, waiting for Canada’s response to their visa application. It was a strange, lonely, and uncertain time—m’loy, m’heuy, they weren’t coming or going.

Their saving grace came in the form of a young man, Ah Sang, the son of one of Ah Thloo’s housemates from the nui oak in her home village, who was waiting for his own travel visa to go to Australia. Ah Thloo was grateful to have a contact in case she needed help but did not expect him to do much. How much attention and time would an eighteen-year-old boy give to an old married woman and a child?

What a surprise it was when Ah Sang showed up at their door one day and asked if they had time to go out. He was like an angel to them during that period and an attentive big brother to Ah Wei. He took them sightseeing several times. One exciting adventure was a trip up to the exclusive lookout at Victoria Peak. Ah Wei clutched his mother’s legs and hid his head as they rode the cable tram up the steep hill. The higher they rode, the broader grew the view—of the city, the harbour, and the islands of Lantau and Lamma. Even more stunning were the sprawling mansions perched on the hillside.

“Yes, those are actually houses,” Ah Sang confirmed when Ah Thloo asked.

“They live like the old emperors!” It was hard to believe the Chinese Revolution had not extended this far.

They had pictures taken on the promenade. Ah Wei was posed in front of an expensive-looking sedan, smart in his white shirt, short pants, and suspenders. Unfortunately for them, Ah Sang’s visa came through in 1953 and he left them to start his new life in Australia. Before he left, he pledged to keep in touch with Ah Thloo, and although they did not formalize their relationship as Ah Thloo had done with Ah Ngan Jean, they acted as if they had, for the rest of their lives.

• • •

Throughout this time in limbo, as the bureaucratic wheels advanced one slow cog at a time, Ah Thloo tried to keep busy. In Canada, Ah Dang was reinventing himself again. They kept in touch by mail.

Ah Dang encouraged her to enrol Ah Wei in school; it would give the boy some structure and a head start in learning English. He suggested the English name of “Robert” for his son, in the event the school required one for enrolment.

Ah Thloo found a good school a short bus ride from their apartment. Ah Wei’s teacher told her that the boy was an obedient student but got frustrated when he didn’t understand a new concept.

Ah Dang sent her two pieces of the best news in December 1953. The first was that the Canadian Immigration Department had approved their applications. He sent her instructions for the next steps in the process: she would have to meet with the superintendent of Canadian Immigration, bringing passport-type photographs, and arrangements would be made for free medical exams, including X-rays. His other news was that he had joined some Chinese friends to run a restaurant. The group had just bought an existing business and was fixing it up to open in the coming year. He noted that one of the partners had a son the same age as Ah Lai and a daughter the same age as Ah Wei; they could all be friends. He wrote, “You are making my dreams come true. First my family will be together. Now I will be a businessman! I hope you and our son will be in Canada in time to help me celebrate the opening.”

Ah Thloo wrote back to congratulate him but was sad to report that for some reason, there were to be delays of several months at the Immigration Office. She sent her husband a photo of them at the Peak.

Ah Dang reported on the official opening of the restaurant. The China Garden Café, Ltd., at 1240 Stanley Street, across the square from the Sun Life Building, started business on March 23, 1954. The full-sized window facing the street was filled with congratulatory baskets of bright flowers from surrounding businesses. All day and night, people kept coming in to buy a cup of coffee and have a free almond cookie. Some even stayed for a meal. Ah Dang said they were right not to go to Hong Ngange gai, Chinatown, where only Chinese people shopped; the Thlai Ngange, Western people, spent more money on eating meals out.

Ah Thloo was happy to hear of his success but also expressed her hope of living in Chinatown, if that was where she could converse with people of her own kind. “What is coffee?” she added.

Ah Dang told her he had found a second-storey walk-up apartment on de Bullion Street, just a short bus ride from Chinatown. He warned her that it was not as spacious as their house in China, but it was all he could afford for now.

Ah Thloo’s next news was not good. The Canadian Immigration Office had sent a letter with an appointment for August 24, 1954, requiring Ah Thloo and Ah Wei to show evidence of immunity from smallpox within the last three years, but they had no such papers. She was arranging for vaccinations.

Ah Dang was worried that by the time she came to Canada, the weather would be getting cold and instructed her to purchase the warmest woollen coats she could find. Hoping against hope, he also sent her money to buy airplane tickets.

China Garden Café’s grand opening, 1954.

UNKNOWN PHOTOGRAPHER, MONTREAL

On November 22, 1954, Ah Thloo, with the family name of Wong (née Jang), and her given names anglicized as Tue Sue, and Ah Wei, renamed Robert Yuet Wei Wong, were approved to go to Canada. At long last.

• • •

AH THLOO: ALASKA, DECEMBER 24, 1954

Ah Thloo had had many firsts along the journey thus far; the airplane ride literally launched her into the twentieth century. The flight stopped in Alaska, where the plane was refuelled after all the passengers had disembarked. Ah Thloo had looked forward to getting out of the stuffy plane, and breathing some fresh air, but when it landed and she looked out the window, everything was covered in white. Ah Dang had told her about snow, but until that moment, she had not really believed that it could blanket the world. When she and Ah Wei stepped out the door, he laughed at what he thought was smoke coming out of her nostrils, but it was just her breath. He was surprised and delighted to see it coming out of his nose and mouth too.

Their hot meal was loaded in Alaska, and they were served dinner as soon as the plane had reached its cruising altitude. Ah Thloo did not realize they had just tasted their first Christmas turkey dinner. Neither did she understand, at the time, the significance of the date of her arrival, December 24. In the Christian calendar, she later learned, Christmas is a celebration of the birth of hope.

Reunited at last with his family (a part of it, at least), this was the best present Ah Dang could have received. They all posed among his friends in Montreal’s Dorval Airport. In one hand, Ah Dang held his fedora, while the other clasped his young son’s arm. As he looked down at the boy, a grin of happiness and pride lit up his face. His days of being a part-time husband had ended. Even better, he was now the full-time father of his son.

Ah Wei, the object of his father’s attention, was solemn. His big, round eyes looked directly at the camera. The six-year-old looked like a little gentleman in his modern suit, but the impression was offset by the jauntily worn Santa cap on his head.

Ah Thloo stood behind the boy, also looking quite modern with her head of short, carefully permed hair, her expression enigmatic.