Chapter Two

v

Environment, Technology,

and the Origins of War

It used to be that history textbooks about Europe described the period between 1815 and 1914 as an era of tranquility. It is true that during that time period the most powerful countries in Europe tended not to fight with each other. This tranquility contrasted strongly with the era of the French Revolution and Napoleon (1789–1815), when large numbers of Europeans fought and died for the sake of their nations and empires. By comparison, the period from 1815 to 1914 does seem relatively tranquil. The relative absence of warfare between nations allowed for a major burst in industrialization and technological development, which resulted in disruptions, to be sure, even as the overall standard of living rose in most places.

Yet this era cannot honestly be described as an era of complete tranquility. In the middle of the century, major conflicts were associated with the unification of the German and Italian nations. In response to the forces of nationalism, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire fought to stave off disintegration. Meanwhile, Britain and France—and to a lesser degree Germany, Italy, Japan, Portugal, and the United States—expanded their empires overseas. For the most part, their colonies were obtained by shedding the blood of the native inhabitants and, to a lesser extent, the blood of their own soldiers.

The building of nations, empires, and industries was the main feature of European, Japanese, and U.S. history in the period from 1850 to 1914. The times seemed peaceful from the perspective of the industrializing countries, but much of the rest of the world found itself dominated by force. It was hard to resist the industrial countries, which enjoyed a temporary advantage in weapons, communications, and medicine. They harnessed the economies of their colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific to serve their needs, while also reaping profits from investments in parts of the world that were not formally colonized, such as China and Latin America.

Technologically driven dominance fostered a sense of well-being and superiority in the industrializing countries, even as their dominance brought new hopes and miseries to much of the rest of the world. This seems to be a contradiction but many scholars have concluded that it is not. The prevailing political idea of the nineteenth-century industrial countries was liberalism. Liberals believed in the freedoms guaranteed by such documents as the U.S. Bill of Rights, like freedom of religion and freedom of speech. Liberals also believed in free trade and tended to support laissez-faire economic policies, in other words those policies that gave business owners a free hand to regulate their own affairs. Liberalism was associated with progressive causes, like the abolition of the slave trade and the emancipation of the slaves. Liberalism was also associated with revolutionary change. British liberals reformed their parliament in 1832 to make it more representative. Liberals on the European continent were associated with movements to overthrow monarchies and to form new nation-states like Germany and Italy. In the United States, liberalism was associated with the Republican Party and with the Union side in the Civil War. In Japan, liberals were led by the Emperor Meiji as they remade their country into a unified, industrializing powerhouse with a constitutional government.

Nineteenth-century liberalism is most often remembered for its positive political accomplishments, yet liberalism had its darker side. Liberal thinkers believed that free markets and unregulated businesses produced the greatest good for the greatest number of people, but many people suffered through wrenching changes in agriculture and industry. Standards of living improved overall but many people were still miserable. Many liberals turned a blind eye to industrial slums and to rural starvation, too. In the face of mass misery in Ireland during the great famines, or in the working-class neighborhoods of industrial cities like Manchester, liberals often adhered to their faith in free-market solutions, even when the free market did not appear to be helping. Liberals were even able to make themselves comfortable with the use of force to dominate less-developed countries. To liberals it appeared to be folly for Africans and Asians to resist empire-building, because the industrial countries had superior knowledge and technology. Liberal belief in free trade and free government might seem to contradict the spread of empires around the world, but the empire builders often thought that they were doing “the natives” a favor by showing them how to run things. Liberals thought that when Africans and Asians demonstrated that they had assimilated liberal ideas about good government—a process that some liberals likened to children growing up—then they might rule themselves.

With hindsight, it is possible to see that liberal imperialism contained the seeds of its own destruction. In the colonies, Americans, Europeans, and Japanese developed ideas about their own racial superiority that they began to employ in their relations with their neighbors. Many Europeans even began to think of themselves as separate races—a French race, a German race, and an Anglo-Saxon or English race—even though millennia of migrations and interactions between Western European countries made such claims historically and biologically preposterous. Familiarity with warfare against colonial “inferiors” also predisposed Americans, Europeans, and Japanese to think that their armies and navies could conquer each other’s territories.

Empires at High Tide and Low Tide

It seems extraordinary to us today that, only a century ago, most of the countries that were involved in the First World War were empires, but it must be borne in mind that empire has been the most common form of government throughout world history. Three of the principal countries involved in the First World War were governed by emperors: Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Russia. The Austrian emperor presided over a large territorial empire comprising more than a dozen nationalities, but he was limited in some ways by a constitution. The German emperor had fewer constitutional limitations over his homogeneous empire in central Europe, together with a handful of overseas territories in Africa and Asia. The Russian empire spread from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean, and from the Arctic Ocean to the Black Sea, and the Russian emperor had the authority to override all of the constitutional limits that had been placed on him.

To the south, the Ottoman Empire had been fragmenting for some decades and its sultan had recently been made a figurehead by a junta of modernizing reformers. Even so, the Ottoman Empire still held on to significant territories that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, including most of the modern Middle East. Another country, Japan, had a constitutional emperor and a small territorial empire, consisting mainly of Korea and Taiwan. Another small territorial empire was possessed by Italy, which had a constitutional monarch. And another country with a constitutional monarchy, Great Britain, possessed enormous territories overseas, some of which were already making the transition to self-government: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa. France and the United States were both republics but still retained sizeable colonial empires.

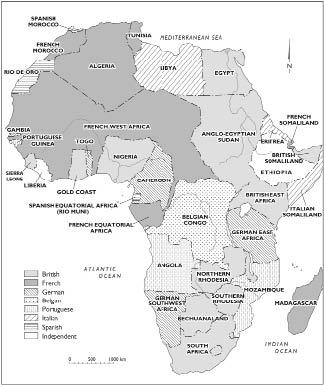

At the start of the First World War, possibly the most interesting fact about world geography was that European empires controlled 84 percent of the planet’s land surface. How was that possible? A hundred years before the war, the figure was much smaller. A hundred years after the war, colonial empires will probably be almost completely eliminated. But in 1914 Europe was at the height of its power relative to the rest of the world. Europe’s acquisition of colonies had accelerated in the 1870s. The First World War would result in defeat for the Austrian, German, Ottoman, and Russian empires. Russia descended into violent revolution, while Austrian, German, and Ottoman territories were partitioned by the Allies. The British and French empires made a net territorial gain during the First World War, even as their economies were stretched practically to the breaking point. It would not be until the Second World War that their overreaching, plus discontent in the colonies, would result in moves toward decolonization.

In each case of an empire expanding its reach, there were particular circumstances that explain colonial domination. Europeans imposed themselves on vast territories in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific for many different reasons. European businesses exploited colonial resources and asked for support in obtaining land and labor. European settlers went out to start new lives for themselves. European missionaries and philanthropists sought to save souls and improve lives.

There were many specific circumstances that fostered European dominance in particular colonies. Some of them have been explained by authors who write about technology and the environment. Jared Diamond argues in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel that European countries were endowed with natural resources that enabled them to excel in the years after 1492, when their economies enabled them to conquer much of the rest of the world. The Western Europeans believed that they were inherently racially superior, but in fact their superiority derived from the way in which they had adapted to natural resource endowments. The peoples of Eurasia simply had more plants and animals to domesticate, while these resources—as well as disease immunities—could be easily exchanged along a natural east-west corridor. Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific, which would come to be colonized by Europeans, did not have such a corridor, nor did they have a similar set of natural resources. Diamond’s explanation helps us to understand that the European colonization of these regions was not somehow the fault of the colonized peoples for being inferior. His work does not shed much light on European empire-building in Asia, nor does he consider the many ways in which modern people have changed environments and natural resources.

A second explanation of European dominance was made in a book by Daniel Headrick called The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century. Headrick asked why imperialism intensified from 1850 to 1920, when the motivations to conquer other countries remained relatively consistent, generally speaking, from 1492 to the present. Headrick argued that, while motives remained consistent, the means of achieving those motives changed in the late nineteenth century. Before 1850, European technology was not vastly superior to the technologies available in the rest of the world. Key developments in the late nineteenth century, notably in medicine and metallurgy, gave Europeans particular, temporary advantages. Research on the causes of malaria, plus the manufacture of quinine, made it possible for Europeans to survive many parts of the tropics that were previously thought to be “White Men’s Graves.” Steam engines and steel ships allowed Europeans to dominate the world’s coasts and trade routes. The invention of the telegraph and the laying of submarine cables under the oceans made it more efficient to administer colonial governments and businesses, as did the development of better railways.

Headrick, like Diamond, places environment and technology at the center of his explanations of European dominance. From the standpoint of explaining the imperialism before the First World War, perhaps the most important developments were improvements in weapons. New weapons were used in Europe, particularly in the short wars that were associated with the unification of Germany and Italy. The struggle over the unification of the United States—the Civil War—was much bloodier, thanks in part to improvements in weaponry. The colonies conquered in the nineteenth century were also a significant proving ground for the new weapons. Firearms technology changed a great deal. Single-shot muzzle-loading pistols were replaced by six-shot revolvers in the 1840s and 1850s. The first semiautomatic pistols appeared in the 1890s and were in widespread use by the First World War. The revolution in rifles was even more spectacular. Midcentury rifles were muzzle-loaders that could be fired and reloaded from paper cartridges two or three times per minute. In the 1860s, most European armies switched to breech loaders, which could fire upwards of a dozen shots per minute, with bullets that were starting to be loaded in metallic cartridges. By the 1890s, breech-loading rifles were equipped with magazines, which increased the rate of fire even more. And the new magazine rifles were firing bullets loaded in metallic cartridges with smokeless powder, which increased the velocity of the bullet while making it easier for the shooters to conceal themselves.

Smokeless powder, metallic shell cartridges, and breech loading were increasingly features of artillery, too. But still the cannons recoiled after every shot and had to be repositioned, reaimed, and reloaded. Starting in the 1890s, new recoilless cannons were equipped with an oiled, pneumatic slide for the barrel, so that a fired barrel slid back and popped forward without rocking the carriage out of position. A cannon that did not recoil and that could be loaded from the breech could be fired a dozen times every minute without reaiming.

In the late nineteenth century rates of artillery, pistol, and rifle fire increased dramatically, but perhaps the most dramatic innovation in firing speed was the machine gun. The first machine guns were produced during the U.S. Civil War. They were hand-cranked devices with multiple barrels that were capable of firing long, dense bursts of bullets. Unfortunately they were also so heavy that they had to be mounted on artillery gun carriages. In the 1880s, heavy single-barrel machine guns were invented by Hiram Maxim. These could achieve a rate of fire upwards of five or six hundred rounds per minute. Their bulk required a team of several soldiers to serve them, and the fact that their barrels were cooled by water meant that soldiers had to continuously drain and replenish the tanks. Even so, they were used to great effect in the colonial warfare of the 1890s. By the time of the First World War, several countries had adopted lighter versions of the Maxim design, while other designs that were even lighter and more mobile were becoming available.

Several wars around the turn of the century demonstrated that the new weapons were transforming the nature of combat. In 1898, a young British army lieutenant, Winston Churchill, participated in the battle of Omdurman in Sudan. This was an engagement that pitted the British army and its Egyptian allies, on the one side, and the forces of the Mahdi on the other. In one of his first books, The River War, Churchill described the futile charge of the “Dervishes,” the followers of the late Islamic leader, the Mahdi, against the British positions. About fifty thousand Dervishes (or Mahdists), armed with outmoded rifles and bearing banners with verses from the Quran, lined up opposite a long line of eight thousand British and seventeen thousand Egyptian soldiers, who had their backs to the Nile River. The Mahdist forces began to charge across an open plain. At a range just under three thousand meters, the British and Egyptian forces opened fire. Remembering the charge of the Mahdists, Churchill wrote:

Did they realize what would come to meet them? They were in a dense mass, 2,800 yards from the 32nd Field Battery and the gunboats. The ranges were known. It was a matter of machinery. The more distant slaughter passed unnoticed, as the mind was fascinated by the approaching horror. In a few seconds swift destruction would rush on these brave men. They topped the crest and drew out into full view of the whole army. Their white banners made them conspicuous above all. As they saw the camp of their enemies, they discharged their rifles with a great roar of musketry and quickened their pace. For a moment the white flags advanced in regular order, and the whole division crossed the crest and were exposed. Forthwith the gunboats, the 32nd British Field Battery, and other guns from the zeriba opened fire on them. About twenty shells struck them in the first minute. Some burst high in the air, others exactly in their faces. Others, again, plunged into the sand and, exploding, dashed clouds of red dust, splinters, and bullets amid their ranks. The white banners toppled over in all directions. Yet they rose again immediately, as other men pressed forward to die for the Mahdi’s sacred cause.

The charge continued. As the Mahdists drew closer, British and Egyptian troops began firing at them from Maxim guns and rifles, too. Churchill continued:

Eight hundred yards away a ragged line of men were coming on desperately, struggling forward in the face of the pitiless fire—white banners tossing and collapsing; white figures subsiding in dozens to the ground; little white puffs from their rifles, larger white puffs spreading in a row all along their front from the bursting shrapnel. . . . The tiny figures seen over the slide of the backsight seemed a little larger, but also fewer at each successive volley. . . . The empty cartridge cases, tinkling to the ground, formed a small but growing heap beside each man. And all the time out on the plain on the other side bullets were shearing through flesh, smashing and splintering bone; blood spouted from terrible wounds; valiant men were struggling on through a hell of whistling metal, exploding shells, and spurting dust—suffering, despairing, dying.1

By the end of the Battle of Omdurman, more than ten thousand Mahdist soldiers lay dead. Thousands more were wounded or taken prisoner. By contrast, on the British and Egyptian side, forty-eight were killed and several hundred wounded.

The new weapons made it very difficult for an army to rush an opponent’s position. In order to attack successfully, armies would have to adapt their tactics. Ideally, attacking forces would need to have numerical superiority. They would also need to precede an attack with a heavy artillery bombardment. It appeared that the new weapons gave defenders a significant advantage. This was seen at Omdurman and time and time again in colonial warfare during the late nineteenth century. It was also seen as early as the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865) and as recently as the war between Russia and Japan (1904–1905). Yet in the years before the First World War, Europe’s armies were not taking these lessons fully into account. Western European soldiers discounted these examples, as they took place outside of Europe, where the professionalism of armies was called into question.

The German Question

In the late nineteenth century, Britain was not the only country to harness new ideas and new technologies to expand its territory. France gained huge new territories in Africa that stretched from the Mediterranean to the Congo, as well as the present-day countries of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Asia’s rising power, Japan, conquered Korea and Taiwan at the expense of the declining Chinese empire. The United States defeated the declining Spanish empire in a short, sharp war in 1898 that resulted in the transfer of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and other islands in the West Indies, plus the Philippines. To many people in the United States and Japan, the old empires of Spain and China seemed ripe for the picking. The United States made promises to nationalists in all their colonies that imperial rule would result in self-governance, but the United States also fought a brutal war against Philippine guerrillas who wanted to achieve independence quickly, on their own terms. Japanese rule in Korea and Taiwan was generally repressive and was deeply resented by Chinese and Korean nationalists.

The American, British, French, and Japanese empires appeared to be on the rise. Several empires, like the Chinese and Spanish, as well as the

Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires, appeared to be in trouble. None had embraced industrialization as quickly or as extensively as the rising powers. The Russians fought the Japanese from 1904 to 1905. The Japanese navy sank a large portion of the Russian navy at the battle of Tsushima while the Japanese army inflicted heavy casualties on the Russians at the battle of Mukden. Russia faced challenges within its borders, too, both from moderate politicians who wanted to put constitutional limits on the tsar and from socialist revolutionaries. National groups within the Russian empire, including Finns, Poles, and Ukrainians, clamored for independence, while the empire’s large Jewish population experienced—and resented—terrible periods of persecution known as “pogroms.” Many Jews turned to Zionism, the belief in the creation of a separate Jewish state. Independence movements were strong in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, too. Ties of personal loyalty to the Catholic, German-speaking Austrian emperor no longer appeared likely to keep in check the national aspirations of the empire’s Catholic Croatians, Czechs, Hungarians, Italians, Poles, Slovaks, and Slovenes, not to mention its Orthodox Serbs, its Bosnian Muslims, and a number of other ethnic groups who were Catholic, Orthodox, and Muslim.

The new empire of Germany sought to find a role for itself in the era of industrialization and empire-building. Germany was industrializing rapidly and was exceeding all other nations in the quality and volume of its productivity. All the while, German agriculture remained highly productive. German universities were generally recognized to be the best in the world, while German literature, music, and philosophy were widely admired, too. Yet this was not enough for many Germans, who wished their country to have a colonial empire as well as a dominant army and navy. The First World War’s origins stem largely from the rise of Germany to the status of a great power. For this reason Germany’s rise requires careful explanation.

Before the 1840s, the German-speaking people of Central Europe did not have their own national government. Instead, Germany was divided into many different countries with many different sorts of governments. Between the 1840s and the 1870s, Germany was united by the government of Prussia, a state centered around Berlin in the northeastern part of Germany. Prussia was led by kings from the Hohenzollern family with the help of brilliant aristocratic politicians like Otto von Bismarck, who led the negotiations for Germany’s new federal constitution.

Prussia united the small, German-speaking states of Central Europe into one federation by means of alliances and warfare. The final war of 1870 resulted in the incorporation of the southwestern state of Bavaria. This move was resisted by the French emperor, Napoleon III. The French were defeated by the Prussians, who seized the French provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, on the west side of the Rhine River. Major upheavals in France resulted in the collapse of Napoleon III’s government. Napoleon’s imperial government was replaced by a republic, while French nationalists nursed a grudge against Germany for seizing French territory. A French man, Robert Poustis, recalled that “When I was a boy, in school and with the family, we often spoke about the lost provinces—Alsace-Lorraine, which had been stolen from France after the war of 1870. We wanted to get them back. In the schools the lost provinces were marked in a special color on all the maps, as if we were in mourning for them.”2 This widely shared sense of grievance was palpable and it even found its expression in imaginative geographical representations on maps. These imaginative representations flew in the face of some complex realities. Alsace and Lorraine contained many German-speakers as well as quite a few people who spoke both German and French. Like many parts of Europe, it was an ethnic and linguistic hodgepodge that became subject to strident nationalist claims.

After defeating the French and incorporating Bavaria, the German federation was renamed the German Empire. Germany faced two related problems, one internal and one external. The external problem had to do with geography and the frequently expressed aim of French nationalist politicians to regain Alsace and Lorraine. So long as Germany held Alsace and Lorraine, it could count on France to be an enemy. With an enemy on the western border, the Germans had to make sure that they had good relations with their neighbors to the east, in Russia, and their neighbors to the southeast, in Austria-Hungary. The Austrians at least shared a common language with Germany and, in many respects, a common culture. That was not the case with Russia. It became a central preoccupation of German diplomacy in the 1870s and 1880s, as the German government worked to ensure that Russia remained friendly—or at least neutral. Relations with Britain were important, too. Britain possessed the world’s largest navy, which could easily choke off Germany’s access to the North Sea and the wider world. Britain had a long-standing policy of avoiding alliances with other countries. This made an alliance between Britain and Germany unlikely. It was also important for Germany to remain on cordial terms with Britain, so that Britain would not be driven to change its policy and ally itself with France.

Germany’s external, geographical predicament was tempered by an internal political problem. In 1848, revolutions swept western and central Europe, with socialists playing prominent roles in the upheavals. Socialist threats to abolish private property and to have governments own farms and factories frightened the middle classes, who were prospering as Europe industrialized. In order to fend off socialism, middle-class Germans threw their support behind the unification of Germany under Prussian leadership, even though this meant that they would be governed by autocratic emperors and their supporters in the Prussian military. Government by soldiers and emperors was preferable to government by socialists—at least the emperor would not take away middle-class property.

The downside to this bargain for educated, middle-class Germans was that the new government was not fully accountable. The legislature was divided into two parts. The upper house comprised representatives of the states. The lower house was elected by all males over the age of twenty-five. The legislature had the right to approve the imperial budget and to regulate the size of the military. It authorized numerous national institutions, including the full range of national bureaucracies. But beyond domestic affairs its powers were limited. The legislature had no control over the army, navy, or foreign affairs, which were the prerogative of the kaiser. He continued to appoint all officers in the Prussian army, who swore an oath of personal loyalty to him, not to the imperial government. The imperial armed forces were dominated by Prussia, although leaders of the other states appointed their own officers. The Prussian king’s chief minister, the minister-president, managed civil and foreign affairs, but even he had little influence over the generals, who answered directly to the king. As Prussia formed the new German Empire by federating itself with more German states, the king of Prussia became the German emperor, or kaiser, and his minister-president became the German chancellor. Each state retained its own government, law, and tax system, although a national tax was also put into place in most states. Most states also participated in national postal and telegraph systems. All state armies were commanded by the kaiser, who took control of collective foreign policy, too.

The Prussian system worked well enough so long as the kaiser was dependable. Dependability was certainly one of the traits of Kaiser Wilhelm I, who ruled from 1858 to 1888. He was an authoritarian who relied on his highly resourceful, conservative minister-president, Bismarck, to achieve German unification. After unification was achieved in 1870, Bismarck crafted a foreign policy that recognized Germany’s geographic vulnerabilities. The enmity of France was guaranteed, so Bismarck secured treaties with Germany’s other neighbors that aimed to isolate France and to protect Germany’s southern and eastern borders. The key to security in the south and east was to prevent conflict between Austria-Hungary and Russia over former Ottoman territories in the Balkans. In 1873, Bismarck orchestrated an agreement between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia called the Three Emperors League. This was not a formal alliance, but an undertaking on the part of Austria-Hungary and Russia to allow Germany to mediate their disputes. The league faded in the late 1870s but was renewed in 1881. In the meantime, in 1879 Bismarck negotiated an alliance with Austria-Hungary, the Dual Alliance, which expanded to include Italy in 1882 and then was known as the Triple Alliance. The Austrians and Russians were not willing to sign an alliance, but, to avoid war with Russia, in 1887 Bismarck negotiated the Reinsurance Treaty, which stated that, if either Germany or Russia were attacked, the other country would remain neutral. Given the limitations of geography, the enmity of France, and the hostility between Austria-Hungary and Russia, this was the best possible diplomatic solution.3

German foreign policy was controlled by the kaiser, who delegated authority to the chancellor. Chancellor Bismarck served at the pleasure of Kaiser Wilhelm I. When Wilhelm I died in 1889, he was succeeded by his son, Friedrich, who died after only three months. Friedrich’s son, the thirty-year-old Wilhelm II, then succeeded to the imperial throne. Kaiser Wilhelm II was aggressive and unbalanced. An accident at birth left him with a crippled left arm. He compensated for his physical disability by making public appearances in a wide array of fancy naval and military costumes; by making a point of excelling at riding, shooting, and other physical activities that were not easy with one arm; and by gaining a reputation as a domineering yet superficial conversationalist and speechmaker. He was overbearing and insecure—not the sort of dependable leader who could be relied upon to manage Germany’s delicate internal and external problems.

Kaiser Wilhelm II clashed immediately with Bismarck over social policy. Wilhelm favored social reforms as a way of persuading working-class voters to turn away from socialism; Bismarck favored repression. In 1890, after socialists made gains in the elections to the legislature, Wilhelm fired Bismarck. Bismarck’s successor as chancellor, Leo von Caprivi, persuaded Wilhelm that the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy was inconsistent with the Reinsurance Treaty between Germany and Russia. They dropped the Reinsurance Treaty and strengthened the Triple Alliance. Almost immediately, Russia began to negotiate with France. France and Russia drew closer over the course of the 1890s, and by 1899 the two countries had signed a military alliance. They pledged to attack Germany if either country were attacked by Germany. Even if Germany or its allies mobilized their armies, France and Russia pledged to mobilize theirs.4 The alliance between France and Russia was Bismarck’s geographical nightmare come true: Germany was now surrounded by enemies working together.

This fundamental problem in diplomacy and geography came to dominate the thinking of Germany’s military planners. It was related to a fundamental problem in manpower. The German army was recruited mainly from the countryside. The officers tended to be the sons of landowners while the enlisted men tended to be the sons of peasants. Composing the army in this way ensured that it remained conservative; including large numbers of city-dwellers might make it more liberal. When France and Russia threatened to surround Germany, one possible response would have been to draft more recruits from the city as well as from the country. Such a move did not meet with the approval of most German generals. Urban, middle-class officers were likely to be more critical of policy, while urban working-class men might “infect” the army with socialism. Fearing such a result, the kaiser and his generals tried to make do with the army they had. This decision meant that the German government had to encourage the military reliability of its allies, Austria-Hungary and Italy. And the army would have to plan and train as well as adopt new technologies in order to maximize its efficiency in strategy, operations, and tactics.5

In the minds of some prominent Germans, efficiency was a necessity for survival. A professor and popular lecturer from the University of Berlin,

Heinrich von Treitschke, wrote in the late 1890s that “Without war no State could be. All those we know of arose through war, and the protection of their members by armed force remains their primary and essential task. War, therefore, will endure to the end of history, as long as there is multiplicity of States. The laws of human thought and of human nature forbid any alternative, neither is one to be wished for.” For Treitschke, war was a natural and positive state. His thoughts were echoed by the German general Friedrich von Bernhardi, who believed that war was a natural and positive part of human evolution. In his popular book, Germany and the Next War, Bernhardi wrote:

This aspiration [for the abolition of war] is directly antagonistic to the great universal laws which rule all life. War is a biological necessity of the first importance, a regulative element in the life of mankind which cannot be dispensed with, since without it an unhealthy development will follow, which excludes every advancement of the race, and therefore all real civilization. “War is the father of all things.” The sages of antiquity long before Darwin recognized this.

The struggle for existence is, in the life of Nature, the basis of all healthy development. All existing things show themselves to be the result of contesting forces. So in the life of man the struggle is not merely the destructive, but the life-giving principle. “To supplant or to be supplanted is the essence of life,” says Goethe, and the strong life gains the upper hand. The law of the stronger holds good everywhere. Those forms survive which are able to procure themselves the most favorable conditions of life and to assert themselves in the universal economy of Nature. The weaker succumb. . . . The man of strong will and strong intellect tries by every means to assert himself, the ambitious strive to rise, and in this effort the individual is far from being guided merely by the consciousness of right.6

Not all Germans believed this kind of rhetoric, in which warfare was described as natural and positive. It is significant, though, that Treitschke and Bernhardi were popular and had followers in the military. If enough people came to believe that war was a natural and biologically essential activity, then when a crisis came it would seem natural to take steps toward conflict.

Planning for War

When German generals realized that there was a real possibility of a simultaneous war against France and Russia, they began to develop a plan that maximized the use of available manpower. Manpower— and the capacity of the state to manage it—became the central environmental factor of the war that followed. Another key factor in war planning and war fighting involved soldiers in responding creatively to the challenges of geography and technology. As we have seen, weapons such as quick-firing field artillery, machine guns, and breech-loading rifles were making warfare more lethal. Already, in the U.S. Civil War and in the Russo-Japanese War, soldiers had responded to the new weapons by digging trenches. Keeping armies in trenches for long periods of time was expensive, while waging war without achieving objectives was unpopular. These problems were familiar to generals, politicians, and intellectuals. Karl Marx’s collaborator, Friedrich Engels, predicted in 1887 that there would soon be a devastating war in which eight to ten million people would die. Helmuth von Moltke, retiring as Germany’s chief general in 1890, warned German legislators that wars between European states were no longer going to be small. In the future, there would be a devastating “people’s war” lasting for years. The Polish banker, Ivan Bloch, warned specifically about the deadliness of the new weapons. He predicted that a future war would feature trench warfare, high mortality, and economic ruin. Sadly, Bloch concluded that the nations of Europe would appreciate the nature of the problem and do everything possible to prevent war’s outbreak.7

To make matters more challenging, the French had built heavy fortifications along their relatively short border with Germany and also in the vicinity of Paris. By contrast, Russia, which then shared a long border with Germany, was a vast country. In 1812, when Napoleon invaded, the Russians used their geography as a weapon. They burned their own people’s farms and towns, calculating that Napoleon’s army could not march all the way to Moscow carrying their own supplies. The Russians were correct. Napoleon’s army was defeated and only a remnant made it back to Paris alive.

Germany’s leading generals dreaded the prospect of a two-front war against Russia and France, but, in the event that this should happen, the German general staff made contingency plans. Before the 1890s, such plans were almost entirely defensive. The generals believed that it would prove impossible to break through France’s defenses. Instead, they prepared to defend Germany from a French invasion. In the east, they planned to advance into Russian Poland and build fortifications. An advancing Russian army would hopefully be defeated, but pursuit into the Russian heartland was thought to be a bad idea. When the German generals imagined how to fight a two-front war, they concluded that geography forced them to fight defensively.

In 1891, as the French and Russians were drawing closer to each other, the new chief of the German general staff, General Alfred von Schlieffen, began to work on a bold new plan that would allow the German army to go on the offensive. First the German army would throw most of its weight at the French, whose army could mobilize—or get to the battlefield—relatively quickly. Then, after defeating France, the Germans would transport most of their army to the east, where they would defeat the slow Russian army. German troops would have to be moved quickly to the border with France and then quickly to the border with Russia, a plan that depended heavily on railroads and telegraphs. This could be done according to complex timetables created by German officers. The trick lay in defeating France very quickly.

Schlieffen dedicated his tenure as chief of staff to imagining and planning for this two-front war. During the mid-1890s, he worked on the details of a plan to use heavy artillery to demolish French forts. Much to his chagrin, testing revealed that this might not work quickly enough. Next Schlieffen sketched plans for the German army to go around French fortifications by invading through Luxembourg and the south of Belgium. This would violate the neutrality of these countries and possibly draw Britain into the conflict—Britain guaranteed the neutrality of Belgium by treaty. Britain was likely to have practical problems with a German occupation of Belgium. Belgian ports were only a stone’s throw across the North Sea from the east coast of England. The possibility of provoking the British caused the German generals some concern, but, as the British army was small, Schlieffen discounted it as a short-term threat.

As Schlieffen developed his plan in 1905, he calculated that he needed to strike France even harder than he had thought previously. Now most of the manpower of the German army would line up against France. The left wing, in the south, would withdraw from Alsace-Lorraine back to defensive positions in Germany while the right wing, to the north, would move through all of Belgium and Luxembourg, plus the southernmost corner of the Netherlands, and drive toward the coast. Near the coast, it would turn south in a giant hooking motion to surround Paris from behind. The French army would be surprised and defeated. Paris would fall to the Germans, who would then send most of their troops back east to face the Russians.

Schlieffen’s plan was a gamble. The gamble was based on elaborate calculations about the movement of army units by rail and road, yet even with all the careful study there were few certainties. With training, the German army could be relied upon to mobilize quickly. With planning, the German railroads could carry troops to their destinations. But how hard would the French resist? Would the small Belgian army surrender? Or would it fight and thereby stall the Germans? Would Britain intervene more quickly than was thought possible? Britain and Belgium could only put small forces in the field, but all they had to do was to delay the Germans. If the German attack on France slowed down even by a few days, the Russians might be able to capture Berlin.

The most important variable was the speed of Russian mobilization: how quickly could the Russians get an army into the field and across the German border? Schlieffen calculated that the Germans had forty-two days to defeat the French. The Austro-Hungarian army would help to pin down Russian forces, but only in the southeast. By forty-two days, the Russians would be on the eastern border of Germany, within striking range of Berlin. The massive attack on France made it necessary to leave only a small part of the German army in the east, where it would be used only for defensive purposes. With the Russians bearing down on Berlin, there was no room for error in France. A delay of a day or two could cost Germany its own capital city.

Schlieffen became obsessed with his plan’s details. The key element involved sufficient manpower traversing geography, a basic environmental and technological problem. In a short period of time, was it possible to funnel enough German troops and supplies through Belgium in order to ensure a forty-two day victory in France? The Belgians and French would destroy their railroads, making it necessary for German soldiers to advance on foot. Could the roads hold all of them? On the right or northern wing, Schlieffen planned to deploy thirty army corps, approximately one million men plus their equipment and horses. This was the figure thought to be necessary to defeat France, yet there were geographical limitations to their deployment. Each army corps consisted of two divisions, each with 17,500 men. In ideal circumstances, an army corps did not advance in one long column but in multiple columns running in parallel. If a corps had plenty of parallel roads, it could advance between twenty-nine and thirty-two kilometers in a day. If the corps started at dawn, by dusk the tail end of the column would have enough time to catch up with the head. In Belgium and northern France, parallel roads could be found within one or two kilometers of each other but the front only extended three hundred kilometers. This left only ten kilometers of front for each army corps. Given that there might only be between five and ten parallel roads, a corps could not advance the full twenty-nine to thirty-two kilometers in a day and still have the tails of the columns catching up to the heads. Based on this evidence, the historian John Keegan concludes that Schlieffen’s plan was a geographical impossibility. Schlieffen himself recognized that too few troops were assigned to the northern, right wing. He urged the addition of eight army corps, even though he knew that the roads could not carry them quickly enough.8

After Schlieffen’s retirement in 1906, the German general staff was led by Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, so-called because he was the nephew of the elder Helmuth von Moltke, who had died in 1891. Moltke the Younger diminished some of the military and political risks of Schlieffen’s plan. In the original plan, the German army withdrew from Alsace-Lorraine in order to ensure the strength of the northern flank. Now Moltke hesitated to make Germany vulnerable to a French thrust across the Rhine and made plans to hold Alsace-Lorraine, reinforcing it with several divisions taken from the north. The original plan had the German army crossing through the southernmost corner of the Netherlands, an act that would have created another small but significant enemy for Germany. Moltke’s revision to Schlieffen’s plan eliminated this move. The north wing would not move through the Netherlands, only through Belgium and Luxembourg. With the north wing reduced in mobility and size, it was expected not to range as far into French territory, but it was hoped that its size was still sufficient to defeat the French. Even the revised plan was still offensive and inflexible.

From the 1890s to 1914, French and Russian planners also shifted from defensive to offensive operations. And like the Germans, they adopted inflexible plans that played down the realities of geography and technology. The French made plans between 1898 and 1909 that all involved deploying troops defensively along the French border, with the later plans placing larger numbers of troops near Belgium. The later plans also relied more heavily on the use of army reservists. In 1911, the leading French general, Victor Michel, proposed further modifications along these lines: completely incorporating the reserves with active-duty forces and planning for a preemptive strike into Belgium. Still, even under Michel, the French plans remained basically defensive in nature. But later in 1911, France’s new right-wing government sacked the left-leaning Michel and replaced him with General Joseph Joffre. Joffre developed a plan, known as Plan XVII, that committed the French army to an offensive in order to recapture Alsace and Lorraine. Having restored French prestige, they would then punch into the center of Germany. From there it would be a long, deadly march to Berlin. The French army chose offense over defense for political reasons—right-wing politicians hoped to restore the glory of France. They hoped that they could make such a rapid advance that they could overcome the German army and the defensive firepower of the new weapons.

The Russians resisted French pressure on them to mobilize quickly. Russian generals recognized that the size of Russia and its relative technological backwardness would delay sending the country’s active-duty troops into the field. Its reserve forces could take months. Between 1910 and 1914, the Russian army pledged to help France by mobilizing its most efficient units to attack Germany within sixteen days.9

As the French persuaded the Russians to make specific commitments to deploy troops, they also met with the British, even though the British were not formally allied with them. In 1911, France’s chief general, Joseph Joffre, met with his British counterpart, Sir Henry Wilson, to discuss how Britain’s army of six divisions might be included in Plan XVII in case war broke out on the continent. Wilson began to plan for a British deployment to Belgium. Wilson did not make any definite commitments to Joffre yet it increasingly appeared that Britain would join France against Germany. Many people in Britain saw France as a historic enemy. And the British people, with their ancient rights and liberties guaranteed by their government, were loath to ally themselves with Russia’s autocratic tsar. The British drift toward Russia and France can be explained, in part, by the kaiser’s diplomacy. His desire to challenge British naval supremacy put a real strain on Anglo-German relations.

The Naval Arms Race

Manpower, geography, and technology were the prime considerations as Germany, France, and Russia planned for war. One of the most sensible ways for Germany to overcome the challenges of geography and technology would have been to foster an alliance with Britain. The British government even approached the German government on several occasions. In 1895, Britain floated the idea of an Anglo-German partition of the Ottoman Empire; in 1898, as the French and Russians were moving close toward formalizing a military alliance, Britain and Germany had preliminary discussions about forming one of their own. Such an alliance would have made sense for a number of reasons. Britain’s power at sea and its colonial empire would have complemented Germany’s power on land and its dominance of central Europe. The countries had dynastic ties, too. The British royal family was of German descent. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s mother was the daughter of Queen Victoria, who was married to a German, Prince Albert.

Yet family ties could only help so much. The kings and queens of Britain had influence in British politics but little real power. By contrast, Kaiser Wilhelm II controlled Germany’s army and foreign policy, although, practically speaking, his superficiality enabled his generals and diplomats to run things on a day-to-day basis. If anything, Wilhelm’s personality was an object lesson in the need to saddle monarchs with constitutional limits. One of Wilhelm’s personal quirks was that he simultaneously envied and hated Britain. His animosity was personal. His left arm was deformed because of an accident at birth; he blamed his mother’s physician, who was British. His mother was a pro-British liberal; Wilhelm rejected his mother by becoming an anti-British conservative. Wilhelm embraced German national romanticism, whose adherents typically believed that, while Germans improved themselves by cultivating the arts and philosophy, the British were a crass and materialistic nation of industrialists and merchants.

Wilhelm’s antiliberal, anti-British sentiments, coupled with his impulsiveness, kept Britain and Germany apart. During the late 1890s, without properly consulting German diplomats, Wilhelm publicly supported South Africa’s Boers, many of whom were resisting Britain’s efforts to incorporate their independent republics into a British-dominated South African confederation. As much as Wilhelm criticized British imperialism, he was like many prominent Germans in that he himself was an imperialist. But by the time that Wilhelm II took power in 1888, there was not much left to acquire. Bismarck had initially been skeptical about controlling overseas territories, but in the early 1880s he persuaded Wilhelm I to acquire several colonies in Africa, including the countries known today as Cameroon, Namibia, Tanzania, and Togo. In the Pacific, Wilhelm I also acquired the northeast part of Papua New Guinea as well as several island groups to the north. Under Wilhelm II, Germany acquired several more islands in the Pacific. In 1898, he acquired a more significant possession: the port of Jiaozhou on the north coast of China, which Germany developed as a naval base. In 1899, Germany averted a naval clash with Britain and the United States over the islands of Samoa, when Wilhelm agreed to a partition.

Disputes over small islands in the Pacific were indicative of a larger problem: a naval arms race between Britain and Germany. Between 1890 and 1914, German naval policies challenged Britain’s leadership at sea, thanks in large part to Wilhelm II. He had spent childhood summers with his English relatives at Osborne House, a royal residence on the Isle of Wight, near the Royal Yacht Club at Cowes. Wilhelm became an avid sailor, a hobby that he pursued for the rest of his life. For several years after he became kaiser, he raced yachts at Cowes, where his membership was sponsored by his uncle, the future King Edward VII. The Royal Yacht Club lay only a few miles away from the Royal Navy’s base at Portsmouth. Wilhelm’s visits to the ships inspired him to build a great navy for Germany. In 1904, on the occasion of King Edward’s visit to the German naval base at Kiel, Wilhelm reminisced with his dinner guests: “When, as a little boy, I was allowed to visit Portsmouth and Plymouth hand in hand with kind aunts and friendly admirals, I admired the proud English ships in those two superb harbors. Then there awoke in me the wish to build ships of my own like these someday, and when I was grown up to possess as fine a navy as the English.” The German chancellor, Bernhard von Bülow, altered the transcript of the speech for the press. He removed the kaiser’s anecdotes, lest the kaiser’s juvenile remarks jeopardize the budget for naval construction.10

Naval ships had become very costly, thanks to a revolution in construction. In the early part of the nineteenth century, navies relied on wooden sailing ships. Large, triple-decker ships of the line, bristling with ninety cannons, fought the main battles. Faster, lightly armed frigates patrolled the seas and protected merchant vessels. At midcentury, sails were replaced by steam engines; wooden hulls were replaced by steel; and cannons peering through portholes were replaced by gun turrets rotating on the main deck. The battleships of the 1880s and 1890s typically mounted four large guns with a diameter of eleven or twelve inches, two per turret, plus varying numbers of medium and small guns. At the end of the nineteenth century, the British navy dwarfed all other navies, while for the most part its ships were technically superior.

Battleships were costly to build, maintain, and operate, yet Wilhelm and his chief admiral, Alfred von Tirpitz, were determined to build a navy that would rival Britain’s. In 1898 they persuaded Germany’s parliament, the Reichstag, to fund the construction of twelve battleships. In 1900, they obtained a long-term commitment to build nineteen. The German construction program, coupled with the kaiser’s support for the Boers, assured that the British would respond in kind. A naval arms race began, shaped by a technological revolution in naval architecture.

As a rule, larger guns fire farther and more accurately than smaller guns. For this reason, around 1900 naval architects began to contemplate eliminating most of the smaller guns from battleships. In a battle, the most decisive shooting would be done by big guns at long distances. In 1905, Britain began work on a new, revolutionary battleship, the Dreadnought. The ship was bigger than most previous battleships, with a new hull design, heavy armor plating, and new engines with turbines that were faster and more reliable than the older battleships’ piston engines. Most impressively, the Dreadnought mounted ten twelve-inch cannons on five turrets.

The Dreadnought’s trials at sea demonstrated its superiority to the old design. Between 1906 and 1913, the British produced thirty Dreadnought-style battleships, with increasingly powerful armaments: by 1913, the new battleships were mounting fifteen-inch guns. Britain also produced ten Dreadnought-style battle cruisers, ships that had weapons and engines that were similar to the battleships but which had less armor. Less armor resulted in greater speed at the cost of greater vulnerability.

Germany responded by building its own Dreadnought-style battleships and battle cruisers. This posed a problem: the ships would be too large to pass through the Kiel Canal, which connected the North Sea to the Baltic Sea. The Reichstag funded the widening of the canal as well as the enlargement of previously authorized battleships. In 1908, the Reichstag passed another “Naval Law” that allowed for the construction of three Dreadnought-style battleships each year. All told, from 1906 to 1913 Germany built nineteen Dreadnought-style battleships and seven battle cruisers. Germany was not able to match Britain battleship for battleship, but now the German navy did pose a significant threat to British dominance at sea. Other countries got into the act, too. Austria-Hungary built four; France built seven; Italy built six; Japan built six; Spain built three; Russia built seven; the United States built fourteen. Argentina bought two from the United States; Brazil bought three from Britain.

Britain met the challenge from Germany but the numbers of Dreadnought-style battleships do not tell the whole story. Many navies relied on smaller ships, too, including medium-sized cruisers and smaller destroyers. These could move more quickly than battleships and were better suited to protecting coastlines and trade routes. Smaller destroyers and a new type of ship, the submarine, could lay mines and fire torpedoes. These were weapons that posed a significant threat to all ships, including battleships.

All battleships were not created equal, either. Germany had fewer battleships, but they were better-designed and better-built than their British counterparts. German guns were lighter and made from better-quality steel. They fired shells propelled by better-quality powder that was contained in safer casings. German gun turrets were safer, too. German ships also had better armor than the British ships, as did the ships of Japan and the United States. Recognizing that heavy shells fired from long distances could hit the sides and also plunge onto the decks of ships, German, Japanese, and American designers armored the top decks, while the top decks of British ships remained relatively thin. German machinery and optics were superior, too. Even though many Germans thought that they had lost an expensive arms race against Britain, in fact their fleet was quite formidable. Used in the right ways, it could pose a significant threat to Britain.

The construction of the German navy damaged relations with Britain, a country that would have made a useful ally, given that Kaiser Wilhelm II’s botched diplomacy had resulted in an alliance between France and Russia. To the east and west and now out on the North Sea, Germany faced determined enemies. Germany’s main allies, Austria and Italy, were not completely reliable. Germany’s geographic predicament fostered insecurity. Its industrial, military, and naval achievements made it formidable. And its leaders made it dangerous.

The Crisis of 1914

The diplomatic crisis during the summer of 1914 has been the subject of detailed investigations by many scholars. Most agree that the war resulted from unfortunate decision-making on the part of civilian and military leaders who were rushed by the nature of war plans. The war plans, as we have already seen, were created as a way to harness manpower and modern technologies and apply them to the problems of geography and politics. At no point did these plans somehow determine that war would happen in 1914. Even so, awareness of these plans tended to rush decision-making in an era when there was not an international organization, such as a United Nations Security Council, where potential conflicts might be delayed and even defused by discussion.

The First World War began in Bosnia, an obscure province in the southeastern corner of Austria-Hungary. The province, home to Bosnian Muslims, Catholic Croats, and Orthodox Serbs, was acquired by Austria from the Ottoman Empire in 1878 and formally annexed in 1908. Nationalist Serbs resented the annexation, hoping to unite Bosnia with the neighboring, independent country called Serbia. On June 28, 1914, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, Sophie, visited the capital of Bosnia, Sarajevo. As Franz Ferdinand and Sophie were riding in their car, a nationalist Serb, Gavrilo Princip, shot them to death. Princip had connections to the Serbian intelligence agency, as the Austrian investigators learned soon after.

Austrians perceived that their empire’s honor was at stake. On July 23, the Austrian government sent an ultimatum to Serbia, demanding that the Serbian government cease anti-Austrian activities. Austria also demanded that Serbia try the Serbs implicated in the plot against Franz Ferdinand, with Austrian officials supervising the proceedings. The Austrians expected a decision in forty-eight hours. These sorts of demands were thought likely to cause a war, but just a war between Austria and Serbia. The Serbs had some public support in Russia but the Russian government did not have a reason to fear for its security if Austria attacked Serbia. The Austrian leadership might have confined the war to Serbia, had they not been concerned that the European alliance system might lead to war with Russia. Austria asked Germany for support, which it got: the kaiser promised Austria that it would have “Germany’s full support.” However, he did not believe that Russia and France would be drawn into the conflict; otherwise he probably would not have taken a vacation on the royal yacht immediately after giving Austria the “blank check.”

Facing these demands from the confident Austrians, the Serbs might have capitulated or they might have given in to most of the demands and negotiated Austrian supervision of their courts. Instead, the Serbian ambassador to Russia sensed that the tsar and his advisers were becoming supportive. He wrote to his home government in the Serb capital, Belgrade: “The Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs [Sergei Dmitrievich Sazonov] sharply criticized the ultimatum of Austria-Hungary. Sazonov told me that the ultimatum contains demands that no state could accept. He said we could count on Russian help, but he did not explain what shape or form that help would take. Only the tsar could decide, and they have to cooperate with France as well.”11 On July 25, just before Austria’s forty-eight hour deadline was about to expire, the Russian government announced that it was taking preliminary steps to mobilize its armed forces, initiating what it called the “Period Preparatory to War.” Russian soldiers were put on alert, while the reservists in some western districts were told to report for duty. This was not a full mobilization, but it emboldened the Serbians, who rejected the Austrian demands.

It appeared that Serbia and Austria-Hungary would go to war and that Russia might go to war against Austria-Hungary on the side of Serbia. In the next several days, Russia took steps to make ready about half of its army. This half-readiness had to be improvised—plans only existed for full mobilization against both Austria-Hungary and Germany at the same time. Troops were not made ready near the border with Germany, only near the border with Austria-Hungary.

Partial mobilization did not satisfy the generals in Austria-Hungary, Russia, or Germany, all of whom wanted the strongest possible defense against external aggressors. Behind the scenes, generals pressed politicians for full mobilization, even as diplomats from many countries scrambled to initiate peace talks. Some of the strongest initiatives for peace came from Germany. Kaiser Wilhelm exchanged telegrams with Tsar Nicholas, while the German chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, pressed his Austrian counterpart, Count Leopold Berchtold, to negotiate with Russia. Russia’s mobilization was only partial but it did still threaten to put millions of soldiers on the border with Austria-Hungary. Austrian generals sought to respond by fully mobilizing their own smaller army.

The problems of diplomacy and war-planning were inextricably linked in Germany, too. The lead general, Moltke, worried that if Russia had some troops ready on the Austrian border they might throw off the complicated timing of Schlieffen’s plan. As it was, the German generals feared that they might not be able to defeat France quickly enough to send troops back east and fight the Russians who would be advancing on Berlin. If the Russians got a head start of even one or two days, Germany could lose the war. On July 30, Moltke went over the head of the kaiser and communicated directly with Austria’s chief general, Baron Conrad von Hötzendorf, telling him that if Austria would order full mobilization, Germany would surely follow. This had not yet been decided by the kaiser, actually, but it persuaded the Austrian leaders to order a full mobilization on July 31. Simultaneously, Russia’s chief ministers and generals, together with the French ambassador, Maurice Paléologue, met with the reluctant Tsar Nicholas to persuade him to order general mobilization. They made the argument that partial mobilization was proving impracticable from a military standpoint. They hoped for a general mobilization, even though they realized that Germany would interpret such an act as a provocation. Without an immediate general mobilization, the generals feared they might suffer greater losses in a war with Germany, especially if Germany sided actively with Austria-Hungary in a war against Russia over Serbia.

By this point, both sides had reached an impasse. On July 29, Nicholas decided to issue the order, but hesitated because of an exchange of telegrams with Kaiser Wilhelm. Wilhelm pressed Nicholas to refrain from intervening in Austrian actions against Serbia. On July 30, Nicholas’s advisers persuaded him that any further hesitations would be dangerous to Russian forces. The next day, July 31, Nicholas ordered all Russian reservists to report for duty. At this point Nicholas sensed that, for diplomatic and technical reasons, mobilization could not be stopped. He sent a telegram to Kaiser Wilhelm stating that “it is technically impossible to stop our military preparations which were obligatory owing to Austria’s mobilization,” even though he also believed that “we are far from wishing war.”12

Learning of Russian mobilization, the German government issued an ultimatum to Russia that proved to be the final straw: in twelve hours, Germany would begin to mobilize unless Russia stopped. A further note was sent from Berlin to Paris. Since France and Russia were bound to fight together against Germany in the event of German mobilization, then war between Germany and France was bound to happen if Russia did not stop its mobilization. Germany gave France eighteen hours to renounce its obligations to Russia and declare its neutrality. France and Russia ignored Germany’s demands. On August 1, Germany declared war on Russia. On August 2, Germany gave Belgium a day to grant permission for German troops to cross its territory. The Belgians did not agree and German troops began to enter Belgium. That day, August 3, Germany declared war on France.

France did not have a formal alliance with Britain, just a cooperative relationship. For several years, the British and French military authorities had been involved in joint planning. In spite of these tentative plans, during the crisis of July 1914 the British cabinet had members who hesitated to enter the war on the side of France. The prospect of a French defeat, coupled with the prospect of German domination of Western Europe, did not sit well with British economic and political interests. Even so, some politicians still doubted whether a German victory over France would provide Britain a pretext for war. The German invasion of Belgium provided that pretext: Britain had signed a treaty guaranteeing Belgium’s territory, and, more importantly, German occupation of Belgian ports threatened the east coast of England. On August 4, the British government gave Germany a day to cease operations against Belgium, or else Britain would declare war. Germany ignored the demands and Britain carried out its threat. The wealthiest and most powerful European countries were now at war. Out of all the great European powers, only Italy held back—for a time.

Europe’s military and political leaders all worried that, if they delayed mobilization, other nations might get the jump on them. As Kaiser Wilhelm said in a telegram to Tsar Nicholas on July 31, “I now receive authentic news of serious preparations for war on my eastern frontier. Responsibility for the safety of my Empire forces preventive measures of defense upon me.”13 All major European countries had complex plans for rapid mobilization, while Germany and France were particularly committed to complex offensive plans. The timing of the plans pushed them toward quick mobilization. As John Keegan and other historians have shown, throughout late July and early August of 1914, leaders could have chosen to negotiate rather than to mobilize. And even after mobilization, the war plans could have been thrown away. For all his bluster, the kaiser considered doing just this. On August 1, he calculated that, if Germany did not attack France through Belgium, Britain would not enter the war, and that Germany could order most of its troops east to engage the Russians. The kaiser was probably right, but Moltke persuaded him that Schlieffen’s plan was Germany’s best hope for victory and that reversing the plan would be too complicated. Hesitation to implement war plans would result in negative consequences. As the French General Joffre explained to Adolphe Messimy, his minister of war:

It is absolutely necessary for the government to understand that, starting with this evening, any delay of twenty-four hours in calling up our reservists and issuing orders prescribing covering operations, will have as its result the withdrawal of our concentration points by from fifteen to twenty-five kilometers for each day of delay; in other words, the abandonment of just that much of our territory. The Commander-in-Chief must decline to accept this responsibility.14

Political and military leaders gambled that they could win in spite of what they knew about the realities of geography and technology. Previous wars had demonstrated the effectiveness of muzzle-loading rifles, while giving a foretaste of newer weapons that were still in early stages of development, such as ironclad warships, single-shot breech-loading rifles, recoilless artillery, and hand-cranked machine guns. These wars in the mid- and late-nineteenth century also illustrated the costs of warfare in the industrial age. It was common knowledge among Europeans that the new weapons gave advantages to defenders. Defenders had such an advantage that it was thought necessary for attackers to have as many as three to five times as many soldiers as defenders for an attack to have a chance at success. At no point did the Entente or the Central Powers have an advantage of three to one. The new weapons should have caused Europeans to hesitate before attacking each other. Such are the judgments made possible by hindsight.

Starting a war was made risky by the realities of defensive technologies. War was made more likely by geographical fantasies. The Schlieffen Plan assumed that the way to get around numerical parity between French and German forces was to attack through Belgium. Yet German planners downplayed a major problem: it was unlikely that sufficient forces could be pushed through the narrow Belgian and French frontier in time to outmaneuver enemy armies. Enough territory would be gained to ensure a conflict. Defensive technologies ensured that it would be difficult for the Belgians, French, and their allies to get it back.

The German leaders were not the only ones to engage in geographical fantasies. The leadership of every country in the Entente or the Central Powers aimed to gain territories, either in Europe or overseas. Overseas, military and naval technologies helped to make these fantasies possible. They remained fantasies, however, because territories were obtained at a time when anticolonial nationalism was building in many places. At the end of the war, newly obtained colonies would be placed under international supervision—under the League of Nations—and almost all of them would become independent nations within fifty years. It would prove difficult for nations weakened by the world wars to hang on to colonial territories.

All of this lay in the future, and, of course, it was impossible to predict the future. This was true except in the case of Grigorii Rasputin, the disreputable faith-healer who had become close to Russia’s royal family. On the eve of war, and suffering from stab wounds received in an attempted assassination, Rasputin wrote to Tsar Nicholas: “Dear friend, I will say a menacing cloud is over Russia lots of sorrow and grief it is dark and there is no lightening to be seen. A sea of tears immeasurable and as to blood? What can I say? There are no words the horror of it is indescribable.”15 Rasputin used natural metaphors: a menacing cloud, a sea of tears, to describe the indescribable. Europe was starting a war in which natural metaphors would be used extensively to convey suffering and misery. In 1914, Europe’s leaders were aware of the perils of launching a massive war. They all gambled against the odds. They all lost.

Africa in 1914

Europe in 1914

The Schlieffen Plan of 1905