Chapter 6

Finding Feminism

Up to this point, Gloria’s journalism career had been a way to pay the bills. She still wasn’t writing about issues that mattered to her. Issues like equality, injustice, the role of women, and racism. But even though she wasn’t paid to report on these things, Gloria began working hard to make the world a better place.

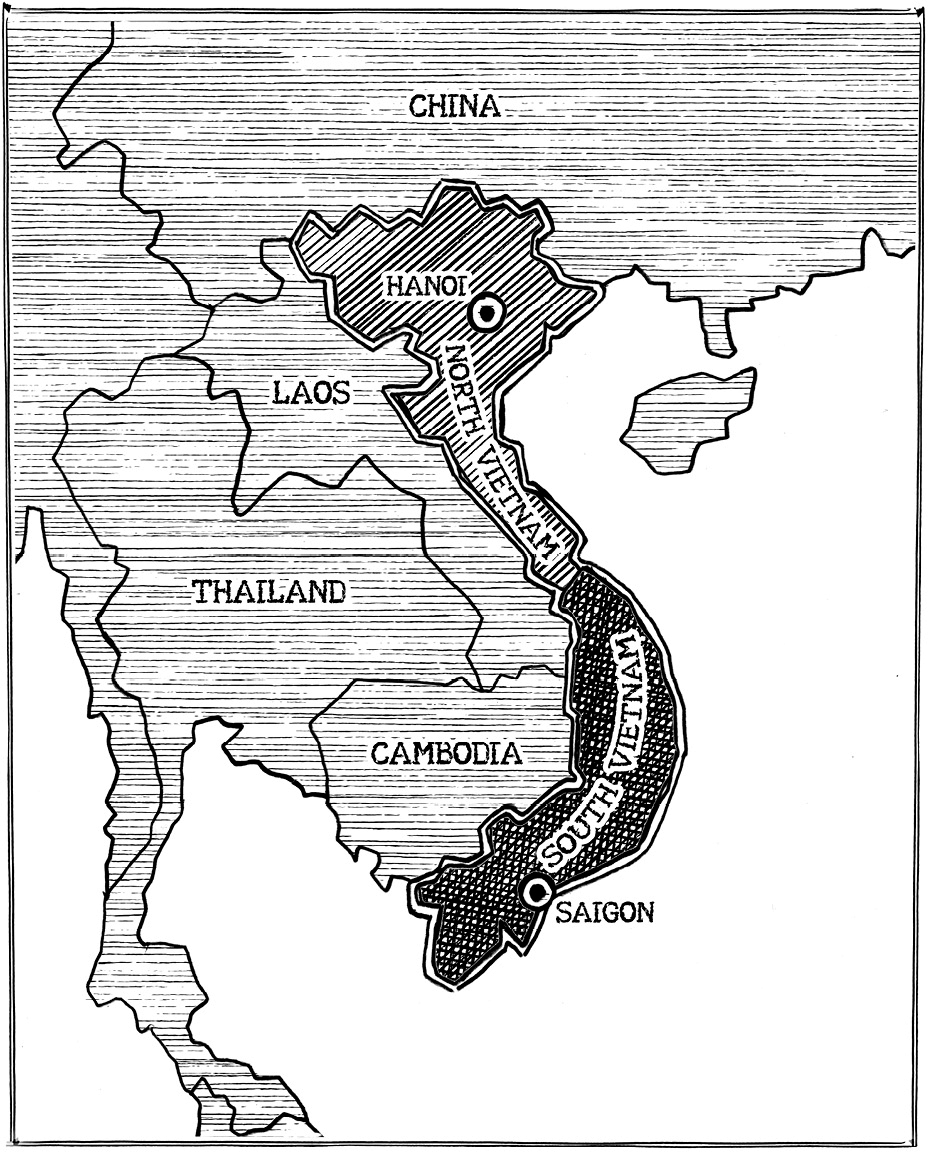

At the time, the United States was involved in the Vietnam War.

The US government had sent troops to help South Vietnam stop North Vietnam from combining the two parts into one communist country. Many people did not want the United States to take part in the war. Gloria was one of them. In 1967, she marched in an antiwar rally in Washington, DC, called Women Strike for Peace.

Gloria also passionately supported the civil rights movement. When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Gloria went to Harlem. She visited this mostly African American neighborhood in New York City to learn how his death had affected the people there.

And Gloria’s interest in women’s rights was never stronger. Women’s issues were becoming important topics in the 1960s. Betty Friedan, who had also gone to Smith College, had written a book called The Feminine Mystique in 1963. The book was getting a lot of attention.

In 1968, Clay Felker, a friend and colleague of Gloria’s, left his job at Esquire magazine. He began developing a magazine called New York that focused on life in New York City. Clay hired a group of writers, including Gloria, to help him get the magazine started. He recognized Gloria’s talent as a writer. He also knew that she understood politics. Gloria became New York’s political columnist.

Finally, Gloria had the opportunity to cover subjects that she cared deeply about. She was determined to report on issues that affected women and other groups that weren’t previously covered in important magazines.

Suddenly Gloria was covering big stories. She wrote about the presidential campaign, the Democratic National Convention, the struggles of the migrant workers’ union, and the growing feminist movement.

Writing about important causes showed Gloria that women were far from being treated equal to men. And this frustrated her. The leader of the migrant workers’ union, Cesar Chavez, thought women should remain wives and mothers. Women attending the Democratic National Convention were not even allowed to give speeches to delegates! And women working on the presidential campaign were still given the least important jobs.

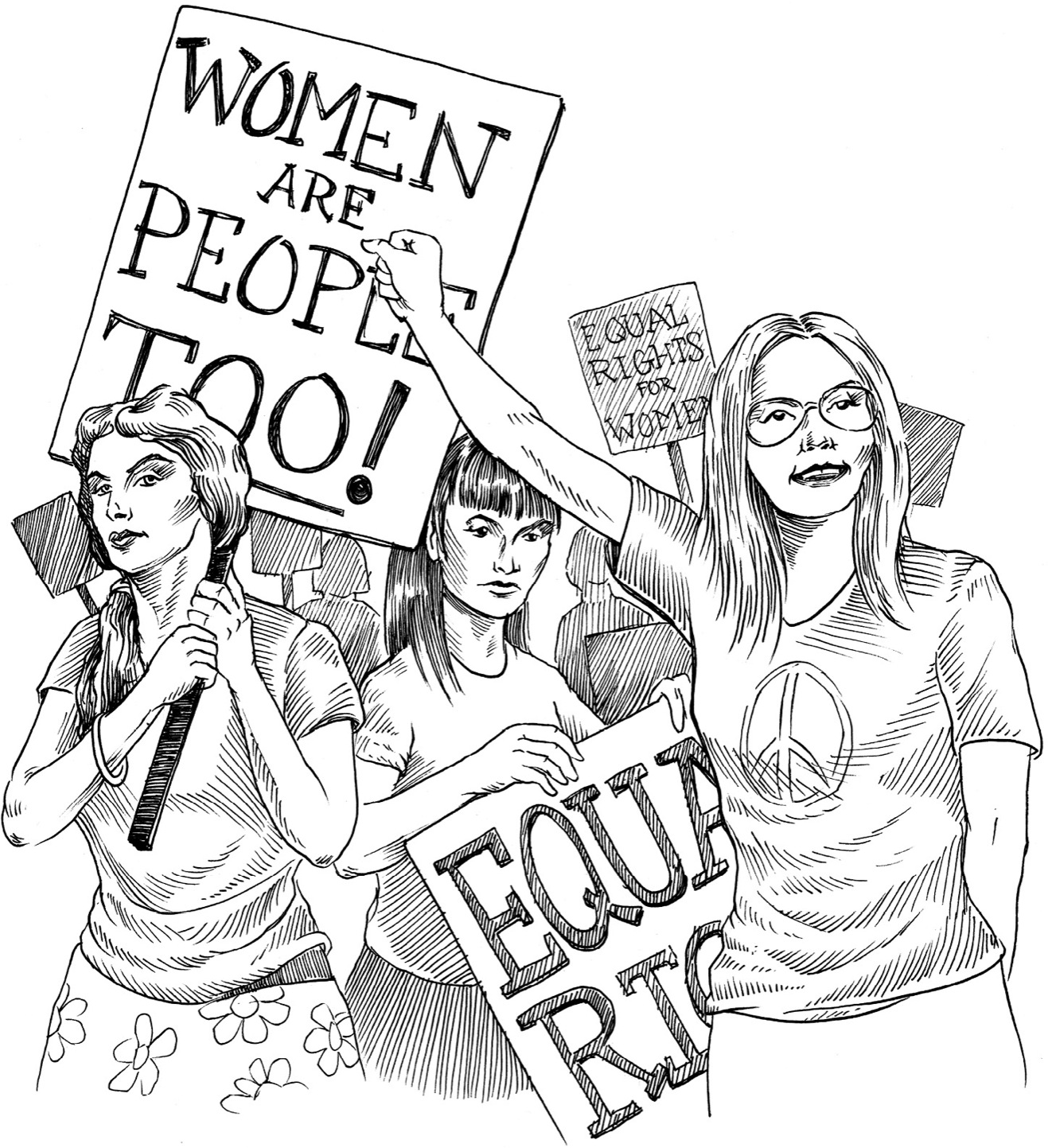

In March 1969, New York magazine asked Gloria to cover a rally. The rally was organized by an outspoken feminist group called the Redstockings.

Gloria was just there to report on the meeting. But it turned out to be an eye-opening event for Gloria and a turning point in her life’s work. Gloria listened to the Redstockings talk about their experiences as women. She realized their stories about having to overcome hardships and prejudice were also her story.

After the meeting, Gloria wrote her first feminist article for New York. It was called “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation.” She talked about how the civil rights movement and the women’s rights movement should work together. Gloria believed that if the two movements supported each other—black and white, men and women—they would both succeed. The article won the prestigious Penney-Missouri Journalism Award, as one of the first reports on the new wave of feminism in the United States.

But some of Gloria’s male coworkers questioned her work. Why had she chosen to write about these “crazy women” instead of something serious and important? They asked her why she wanted to cover “women’s stuff” when she had worked so hard to get “real assignments.” For Gloria, women’s rights were the most “real” assignment.

Those comments confirmed Gloria’s dedication to the feminist movement.

From that point on, no one thought of Gloria Steinem without thinking of the word feminist. Gloria realized that she could also help spread the word about women’s rights by speaking to people. It was a way to “get the word out” when many magazines and newspapers did not want to publish articles about feminism.

Gloria was sometimes nervous about speaking in public. But her desire to spread the word about feminism was stronger than her fear. In September 1969, Gloria spoke to the Women’s National Democratic Club about her prizewinning article. She asked her friend Dorothy Pitman Hughes, an African American feminist, to speak with her. Hughes had opened a child-care center for working mothers—something that was rare in the 1960s. Gloria and Dorothy believed their partnership would show that the women’s movement applied to all women, no matter their age or the color of their skin.