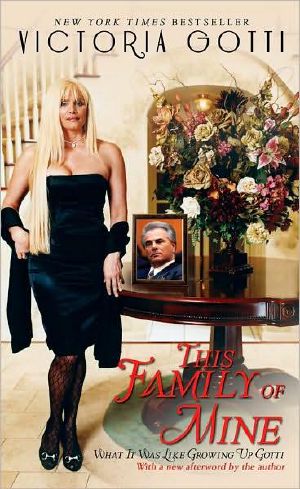

This Family of Mine · What It Was Like Growing Up Gotti

- Authors

- Gotti, Victoria

- Publisher

- Tags

- non-fiction

- ISBN

- 9781439154502

- Date

- 2009-09-29T04:00:00+00:00

- Size

- 2.34 MB

- Lang

- en

THE ASTONISHING NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

The No-Holds-Barred Truth About Life Inside the Gotti Dynasty—Told by Their Most Famous Daughter

Victoria Gotti never intended to reveal the inside story of the Gotti household—the day-to-day life of a family that has sparked scandalous rumors and sensational headlines for decades. But with the pressing need to finally set the record straight came the realization that only she can do so, once and for all. Daughter to the late John Gotti, sister to John A. “Junior” Gotti and three other siblings, single mother to three sons with whom she shared reality television stardom on Growing Up Gotti, an outspoken columnist and bestselling author, Victoria Gotti delivers a candid, colorful, and brutally honest family portrait that reads like a confidential file, filled with deeply personal reflections, bombshell revelations, and stunning insider secrets.

The explosive memoir that captures the Gottis as they are—unvarnished, raw, and real—This Family of Mine is the essential chronicle in the ultimate American family saga.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.Chapter One

"Papa Was a Rolling Stone"

Winter 1952

The door blew open with driving force; shards of wood like shrapnel sprayed the cold, cramped Brooklyn railroad flat. To a twelve-year-old, the U.S. Marshal's arrival came in the form of an unfathomable explosion that would haunt his dreams into adulthood. Two local police officers and one marshal from the housing department had been dispatched to evict a poor and hungry family of thirteen -- despite the fact that Christmas was less than one week away.

My father lay huddled with his six brothers, all forced to survive in one room, on two mattresses, in the musty three-room apartment. It was in the dead of winter and none of the Gotti children -- seven boys and four girls, ages five to sixteen -- had clothing suitable for protection against the elements. Dad would later recall that evening as being not only unbearably cold but accompanied by a dark, empty sky.

The Gotti children were accustomed to sharing tight quarters. If it seemed unnatural, even cruel, it was nonetheless preferable to sleeping on a cold bare floor "or being homeless," as my father used to say. The family bounced around in those years, from a poverty-stricken section of the South Bronx to a modest apartment in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. My grandfather, John Senior, made some money in an all-night card game and moved the family into a middle-class neighborhood; however, it wasn't long before his luck (and money) ran out. Within a few months the Gotti clan ended up in more humble surroundings, a shabby apartment in Downtown Brooklyn. "Times were hard," my father said. "And they were about to get a lot harder."

The eviction in 1952 was swift and heartless. Dressed only in worn flimsy garments, the Gotti children and their mother, Fannie, stood shivering in front of the dilapidated apartment complex that only a few minutes earlier had been their home. John Senior was out that night, off on one of his business trips. Monthly rent on the apartment was a paltry sum, but even that proved more than my grandfather could manage.

Philomena "Fannie" DeCarlo Gotti was a hardworking housewife who often took on odd jobs outside the home -- doing the neighbors' laundry, cleaning apartments, bagging groceries at a local market to help make ends meet. But lately there never seemed to be enough money. The family was barely able to keep food on the table and heat in the apartment. Conversely, my grandfather, John Joseph Gotti, was a perpetual adolescent, forever in search of excitement and fun. An avid gambler, drinker, and womanizer, he rarely held a steady job; whenever he got the "itch," as Grandma called it, he would take off for parts unknown, typically accompanied by some barmaid he'd only recently met.

There were times when Grandpa hit the road on one of his socalled "business trips" and didn't return for months. For a while he had a job as a camera grip for a major film studio and even traveled to Hollywood on one occasion. This failed to result in any sort of legitimate career, but it did produce a handful of entertaining tales. My grandfather was fond of embellishment, and so he would tell anyone within earshot of his work-related war stories, like the time he met Jane Russell.

During the filming of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Grandpa swore the gorgeous actress was attracted to him (forget for a moment the professional chasm that separated the lowly tech and the leading lady), and that she looked for excuses to talk to him. According to his story, she even winked at him on occasion.

Then there was the time he met Tony Curtis at the studio commissary. Grandpa insisted the two had become fast friends.

"That guy is a class act," Grandpa had often said. Then he would smile and laugh. "Very personable, too."

So instantaneous was their bond that Grandpa and Tony Curtis went out together that very night and took the town by storm. They drank themselves blind, eventually winding up in a seedy motel with a "couple of real lookers." Or so Grandpa claimed, anyway.

The odd brush with greatness apparently was far more important to my grandfather than the mundane responsibilities of family life. It seemed not to matter that he had a large family to feed, or that there was never enough money to pay the rent or heating bill. And every so often, the Gotti family was kicked to the curb.

This naturally produced a degree of cynicism in my father, who years later would erupt any time he read a cliché-ridden newspaper article or book that described Grandpa as a hardworking Italian immigrant.

"These fuckin' bums that write books -- they're worse than us," he would rail. "Lies. All lies! My father was born in New Jersey. He's never been to Italy in his whole fuckin' life. He never worked a day in his life. He was a rolling stone. He never provided for his family. He never did nothin'. He never earned nothin'. And we never had nothin'."

Dad recalled his mother's reaction while standing at the curb on the night of the eviction, in the freezing cold, wearing a tattered sweater over a worn and faded housedress. She was only in her mid-thirties, but looked closer to fifty. The years, overloading her with work and anxiety and neglect, had not been kind to her. Grandma was a "cold woman," Dad often said, hardened by years of sacrifice and disappointment. Mostly, Dad blamed his father for this. A man was supposed to take care of his family: put a roof over their heads, food in their bellies, and keep them warm in proper winter clothing. But, rather than struggle to fulfill his responsibilities and obligations, Grandpa chose instead to run -- usually to the nearest bar to drown himself in his failure as a husband and father.

On this evening my father saw that she was understandably upset. Although Grandma rarely showed weakness in front of her children, the tears streamed down her cheeks. She stared at the old apartment building, then out at the street, and then back to the apartment building. Her eyes, my father noticed, were empty and sad, and the expression on her face frightened him.

The Gotti clan stood shivering outside for nearly an hour that night, a mid-winter drizzle chilling them to the bone. "An hour," Dad said. "But it felt like an eternity."

Exhausted and fearing for the welfare of her children, Grandma finally took action, marching the entire, rain-soaked clan nearly a mile through the streets of Brooklyn to the House of the Good Shepherd, a church-sponsored residence for "wayward girls" (the facility catered to young, single women who had unplanned pregnancies). It must have been painful for Grandma to beg -- she was a proud woman, after all -- but that is what she did. For the sake of her children, she asked for mercy, and Sister Mary Margaret, dressed head-to-toe in black, responded with kindness, showing Grandma and the Gotti children to the building's attic.

In reality, it wasn't really an attic at all; it was a four-room apartment, a conversion made in the early 1940s to accommodate housing needs for the staff. Although the apartment had only an efficiency kitchenette, it was better than nothing, and Grandma saw its potential. The living room was really more of an alcove, adjacent to the kitchenette; it would likely serve as a fourth bedroom for the oldest male children. The two other rooms would be shared by Grandma and the remaining children, including my father, at least until Grandpa could find his way to the family's new home. No one knew when that would be, but at that point, one of the three bedrooms would then be used as a master, resulting in eleven children sharing two small rooms. Tight quarters, to be sure, but, as Dad explained, "It was definitely better than the alternative."

The days that followed would prove nearly as bleak. At the age of twelve, Dad was forced to hit the streets and find work, as were the other Gotti children. Everyone was expected to pull their own weight, especially the boys.

Dad combed the neighborhood looking for employment. Options, he quickly learned, were limited. A corner service station on Fulton Street had recently dismissed two mechanics in an effort to cut costs. A local deli already had two full-time day workers and three part-time night staffers. The manager at the AP supermarket offered little encouragement, telling Dad he was too young for anything but carrying bags for customers. My father gave that one a moment's consideration before spotting a crowd of eager boys fighting over customers in the parking lot. Realizing that his pay would consist only of tips, and that the store already seemed overstaffed, he walked away.

Not enough customers, not enough hours, not enough money.

Six weeks later, my grandfather ambled down the street to the House of the Good Shepherd, having easily tracked the family down through a network of friends and acquaintances. Along the way, he'd been told of the eviction and the dire circumstances faced by those whom he had abandoned. If his father felt guilt or remorse, Dad said, it wasn't readily apparent. Accountability was not high on Grandpa's list of virtues. He preferred to play the victim, forever damning the world and cursing God for having dealt him a raw hand. And so he rationalized his behavior and his vices -- the alcohol, gambling, loose women, and the nasty temper as well.

Grandpa turned up at the attic apartment late one night, itching for an argument with my grandmother. At first he rang the bell and waited patiently, but there was no answer. After three tries, he began pounding the door like an impulsive child -- pounding and kicking with such force that Sister Mary Margaret nearly called the police. Realizing who the belligerent man was she told him, "Please, sir. Use the top bell."

Meanwhile, oblivious to the commotion three stories below, my grandmother and her brood slept peacefully. Of all the Gotti children, only two were awake. Dad was restless and couldn't sleep, and one of his younger brothers, I believe Ritchie, was wide awake because he had to go to the bathroom. Since there were seven boys in a single room, and only two beds for them to share, the Gotti...