COLONIAL COLLEGES, 1740–1780

NEW COLLEGES FOR THE MIDDLE COLONIES

IN THE MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, COLLEGES IN the American colonies doubled in number and changed in character. The College of New Jersey (1746), King’s College in New York (1754), and the College of Philadelphia (1755) were chartered and began instruction. The new colleges on the New York–Philadelphia axis were products of the rapid growth of the economies and populations of the Middle Colonies, although each reflected the distinctive demography and religious character of its surroundings. Unlike the settings of the first three colleges, the entire region was populated by diverse peoples with differing Protestant beliefs. However, initially only a few of these groups had any interest in colleges. The growing number of Presbyterians had close roots in Scotland and Ireland, where ministers were expected to be highly educated. In the two cities, upper-class members of the Church of England sought institutions to solidify their social position and ties with English culture. Still, these foundings were interconnected. The Presbyterian initiatives in New Jersey kindled the efforts in New York and Philadelphia. The latter sought Samuel Johnson for its head before he opted to lead King’s; and William Smith’s meddling in the planning for King’s led to his appointment as provost in Philadelphia. Each of these campaigns took nearly 7 years to create a college, and these prolonged processes affected the outcomes. Ultimately, the colleges of the Middle Colonies represented the learning and spirit of the American Enlightenment. But strangely, the catalyst for these developments was the Great Awakening of evangelical religious fervor.

Historians have accorded the Awakening a large role in shaping colonial colleges. However, the most vigorous outbursts of revivalist preaching occurred in the early 1740s, and the lasting schisms they provoked in major churches overlapped with other social and political fault lines. The central figure was George Whitefield, a young Anglican minister who acquired notoriety for his revivalist preaching in London during 1738–1739 while raising funds for a Georgia orphanage. When he returned to America late in 1739, his reputation preceded him.1 Whitefield relied on the publicity of his revivalist exploits in colonial newspapers and the regular publication of his own Journal to heighten public anticipation of his appearances. The colonial equivalent of a rock star, his act and tours were thoroughly orchestrated. Starting around Philadelphia, he delivered nearly 350 sermons during 3 tours lasting through 1740. He estimated that on 61 occasions he preached to crowds of 1,000 or more, and a few reportedly as large as 20,000—more than the population of the largest American cities. He preached in every colony but achieved a huge response only in the Calvinist “revival belts,” consisting of mostly Presbyterians in the Middle Colonies and Congregationalists in Connecticut and Massachusetts—the location of his third tour.

Whitefield was clearly an orator of great talent, able to make listeners acutely aware of the perils of damnation and desperate to improve chances for salvation. He espoused a crude version of old-time Puritanism but sidestepped predestination by offering listeners the possibility of salvation through the conversion experience. The conversion of souls at these revivals was regarded as evidence of the “Work of God,” an interpretation sanctioned by the colonies’ foremost theologian, Jonathan Edwards.2 The transient appearances were part of the performance. He gave only a few well-rehearsed sermons in each locale, stirring religious passions, before moving on and leaving local clergy to deal with the aftermath of anguished souls. These and later revivals had a cumulative effect, becoming more intense in preaching tactics and spiritual impact in the following years.

Whitefield himself seems to have been an amiable fellow who got on well with a spectrum of hosts, especially in his later tours.3 He befriended Benjamin Franklin, for example, who shared none of his “enthusiasm” but admired his eloquence—and may have appreciated the boost Whitefield’s publicity gave to his printing business. Whitefield ingratiated himself with contemporary Puritans by claiming to espouse traditional Calvinism and railing against the Arminianism of Tillotson and the Church of England. However, a crucial tactic of Whitefield’s self-advertisement was to foment controversy, and here the message contained a poison pill. To dramatize his own piety compared with the laxness of existing churches, he made reckless accusations that present ministers were unconverted—lacked a conversion experience—and hence unfit to lead their parishioners to salvation. Although he was cordially welcomed at Harvard and Yale, they received the same treatment. In his published Journal he wrote, “As for the Universities [sic] … Their Light is now become Darkness—Darkness that may be felt—and is complained of by the most godly ministers.”4

Whitefield was soon followed by a succession of imitators, itinerant revivalist preachers who were more extravagant in their preaching and blatant in their attacks. Thus, the Awakening quickly evolved from an apparent Work of God to a challenge to the churches and the two northern colleges. The radicalism and blatant emotionalism of the Awakening soon divided the Reformed churches into New Light adherents and Old Light defenders. Nowhere was the schism more dramatic than at Yale College.

Whitefield spent 3 days in New Haven (October 24–26, 1740), preaching in the college and the town. He was warmly greeted by Rector Thomas Clap, who approved of the spiritual agitation he inspired in Yale students. Among the itinerant preachers who followed, Gilbert Tennent preached for a week in the spring of 1741. A leader among the New Light Presbyterians in New Jersey, he had collaborated with Whitefield, who explicitly encouraged him to “blow up the divine fire” in New England. Tennent was even more emotive than Whitefield and was especially damning toward allegedly unconverted ministers. The Awakening spawned increasing numbers of itinerant preachers, like Reverend Eleazer Wheelock (Yale 1733), who exulted after one revival, “the Whole assembly Seam’d alive with Distress[,] the Groans and outcrys of the wounded were such that my Voice Co’d not be heard.” Perhaps the worst was James Davenport, demented and self-anointed, who one knowledgeable commentator called “the wildest Enthusiast I ever saw.” Thus, the Awakening assumed a radical form that divided congregations, repudiated an educated ministry, and reduced religion to raw “enthusiasm.”5

At this point Clap had seen enough. He helped the colony promulgate a ban on itinerant preachers and eventually deport Davenport as non compos mentis. At Yale, student preaching and proselytizing had completely disrupted the college order. Clap first expelled one of the New Light leaders, David Brainerd, for allegedly saying that a tutor had “no more grace than a chair.” Then, in 1742, he was compelled to close the college and send students home. When it reopened, with the most zealous New Lights pursuing salvation elsewhere, order was restored and the crisis appeared to be over. But Clap was unrelenting against New Light influence in and around his college. He sought to discredit both Gilbert Tennent and Jonathan Edwards. In 1744 he expelled two brothers for attending a New Light service while home with their parents. Like the Brainerd affair, this arbitrary act was widely publicized and fanned controversy throughout the colonies. When the student protested that he broke no college law, Clap replied, “The laws of God and the College are one.” In truth, these were the laws of Thomas Clap, who embraced intolerance and autocracy at a time when colleges were moving in the opposite direction.6

Whitefield attracted enormous crowds in Boston, but the response of the college was much cooler.7 The Harvard faculty flatly rejected his condemnation of Tillotson, and relatively few students were affected. When Whitefield’s disparaging Journal remarks appeared, battle lines were drawn.8 Whitefield returned to New England in 1744 but was now excluded from the pulpits of Harvard and Yale. He responded with renewed attacks. On this occasion, he was answered with a “Testimony” of the president and faculty of Harvard “against the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield, and his Conduct” (1744). This pamphlet condemned him for “Enthusiasm,” for claiming “greater Familiarity with God than other men,” and for “Arrogance … that such a young Man as he should … tell what books we shou’d allow our Pupils to read.” Whitefield’s ineffectual rejoinder was countered by a more thorough denunciation by Hollis Professor of Divinity Edward Wigglesworth. In addition to a blow-by-blow refutation of Whitefield’s accusations, he upheld the college’s Calvinist credentials and accused Whitefield, despite his evasions, of antinomian heresy.9

This incident is testimony to the growing maturity of Harvard College. The appointment of its president, Edward Holyoke (1737–1769), was considered a victory for the liberal faction, and his long tenure was notable for modernizing the curriculum (discussed below). The advancing spirit of the Enlightenment was evident in the Harvard argument that “Reason, or … Revelation of the Mind of God” are better trusted than Whitefield’s “sudden Impulses and Impressions.” Harvard reflected the cosmopolitanism of a great seaport, rather than the religious enthusiasm of the common people who flocked to Whitefield. Harvard also had a professor of divinity with the authority to oppose the celebrity upstart. All these qualities were lacking at Yale.10

Old Lights dominated colonial government in Connecticut, and they rewarded Clap in 1745 with prompt approval of a new charter that made him a member of the trustees. Although this represented a formal elevation of Clap’s status, he increasingly behaved as if he had become sovereign ruler. In an effort to enforce religious conformity, he required all students to attend religious services in the college rather than the town. To justify this action, Clap wrote: “Colleges are Societies of Ministers for training up persons for the work of the Ministry.” And Clap himself became the arbiter of the nature of that training. He stiffened the religious tests for all teachers and denied students access to liberal books in the library. Clap’s obsessions may have been reactions to the Awakening, but they soon became more personal than theological. Withdrawing Yale students from New Haven’s First Church alienated Old Lights, but he failed to placate New Lights, even when he reversed course and welcomed Whitefield into the college in 1754. Clap’s autocratic ways earned him increasing numbers of enemies, which would be his undoing when he lost control of the college in the 1760s.11

★ ★ ★

The split between old-light and new-light Presbyterians in the middle colonies began before Whitefield’s arrival and from the outset raised the issue of ministerial education. Most local ministers had been trained in Scotland or New England, but by the 1730s their numbers could not match the rapid growth of congregations. Some new ministers, especially among recent Scots-Irish immigrants, were trained individually by local ministers, and almost all favored a new-light style of preaching. This was especially the case with William Tennent, Sr., a master’s graduate of Edinburgh who trained Gilbert and three other sons for the ministry. He then instructed additional ministerial aspirants in a log structure that adversaries dismissively called the “Log College.” The classically educated Tennent instructed his charges in Latin, Hebrew, and a good deal of Bible study; they also imbibed his fervent pietism, to the increasing displeasure of the Philadelphia Synod.12 Both factions attempted to alter requirements for ordination to either facilitate or obstruct these new-light candidates. The conflict prompted the synod in 1739 to consider establishing a school or seminary. The arrival of Whitefield inflamed these tensions and led in 1741 to the expulsion from the synod of new-light presbyteries of New Brunswick and New York. The dominant figure in the former was Gilbert Tennent, who now led the opposition of the Scots-Irish New Lights. The area around New York was home to a group of “New England Presbyterians,” led by Yale graduate Jonathan Dickinson. Each side soon sought the means to educate its own ministers.

In 1743 the Philadelphia Synod officially sponsored an academy in New London, Pennsylvania, under Francis Alison, reputedly the finest classical scholar in the colonies and an opponent of the Awakening despite his Scots-Irish background.13 The school sought to teach at both preparatory and collegiate levels, but the synod’s clear intention was to prepare old-light ministers. The school was supported by the churches and charged students no tuition. An attempt was made to have Yale award its students degrees (which would have made it America’s first branch campus), but Thomas Clap was not encouraging. Alison’s school struggled financially and never attempted to obtain a charter. After he joined the Academy of Philadelphia in 1752, the school migrated to nearby New Ark, Delaware.14

In the New York region, Elizabethtown minister Jonathan Dickinson was an articulate advocate of new-light positions similar to those of Jonathan Edwards. He was appalled by President Clap’s vendetta against the New Lights, but overcrowded Yale was no answer in any case to the need to educate more Presbyterian ministers. On the other hand, Dickinson sought a moderate approach that would bypass radical New Lights, whose excesses had tarnished the movement. This precluded a log-college type of seminary. In 1745 Dickinson formed a group of Presbyterians and Anglicans from both sides of the Hudson who pledged £185 and began formulating a charter for a prospective college. Anglicans soon fell out of this coalition, most likely over the issue of control, but this initiative seems to have planted a desire for their own institution in New York City.15 Seven Presbyterian ministers and laymen persisted and by the end of the year presented a charter to the royal governor. A staunch Anglican, the governor promptly rejected it, stating that he had no authority to authorize a “dissenter’s college.” However, he died in May, and the interim governor was advised by friends of the college. On October 22, 1746, a charter was granted to the College of New Jersey, and classes began the following May in the parsonage of Jonathan Dickinson.

The original charter named seven trustees—three New Jersey ministers and one from New York and three Presbyterian laymen residing in New York—six Yale graduates and one son of Harvard. Thus, the college from its birth was academically a lineal descendant of the New England colleges, offering a “plan of education as extensive as our circumstances will admit.”16 But its organization was distinctive. The trustees had the authority to name five additional members, and they quickly moved to invite Gilbert Tennent—who had mollified his radical views—and three other log-college ministers. By incorporating the most prominent Scots-Irish, the college presented a solid front of new-light Presbyterians stretching from New York to Pennsylvania. Nonetheless, the college proclaimed itself open to “those of every religious denomination,” which was consistent not only with New Jersey freedom of religion but also the practices of Yale and Harvard. Its all-Presbyterian trustees resembled the monolithic governing board of Yale; however, the latter represented the colony’s established church, which was not the case in New Jersey. The new governor, Jonathan Belcher, perceived the weakness of the charter, particularly in the face of Anglican opposition. A new light himself and avid supporter, he worked with the trustees to devise a stronger charter. The new charter of 1748 created a mixed board of twenty-three trustees representing the colony as well as the Presbyterian founders. The governor presided as an ex-officio member, but Presbyterians were assured of a majority. Its church-state governance now paralleled Harvard’s Overseers but had far greater control. Thus, the College of New Jersey constituted a distinctive governance model of a provincial college.

The efforts of Mid-Atlantic Presbyterians to educate ministers for their growing needs resulted, through the efforts of Dickinson, in a liberal arts college open to all. Both these traits proved invaluable for the further development of the college. Efforts to secure Presbyterian control had resulted instead in a mixed governing board that made the college a “public” institution, at least in a colonial sense. However, despite the close identification with New Jersey, it had an intercolonial board. Nor did the province ever support the college; Governor Belcher proposed a lottery to raise funds, but the New Jersey Assembly voted it down.

Jonathan Dickinson died only 4 months after opening the college, but instruction was quickly transferred to founder Aaron Burr’s parsonage in nearby Newark. At this point the college was merely an enlargement of the classical schools that both reverends had provided at their homes (an arrangement little different from Yale’s early days in Killingworth). But the college’s legitimacy was soon confirmed in 1748 when the trustees gathered in Newark for the first commencement exercise. Aaron Burr was elected president, and he then proceeded to award six bachelor’s degrees and a master of arts to Governor Belcher. The new college offered a curriculum nearly identical to that of Burr’s alma mater, Yale.17 Still, the founders were aware that a real college required a permanent home and, above all, a collegiate building. From the outset Governor Belcher had favored “Princetown” in the center of the colony. In the event, the town had to outbid rivals in order to secure the college in 1753. To raise the funds for a building, Gilbert Tennent and Samuel Davies, a new-light minister from Virginia, were sent to England for a year of fund-raising. Old-side Presbyterians and Anglicans attacked Tennent for his former radical views, but the pair succeeded by emphasizing the college’s religious freedom for English audiences and lauding its mission of training Presbyterian ministers for donors in Scotland and Ireland.18 The £4,000 they raised financed Nassau Hall, the grandest collegiate structure in colonial America. When it was occupied in 1756, the College of New Jersey achieved permanence and legitimacy. By then it also had rivals in New York and Philadelphia.

★ ★ ★

The founding of these two colleges was triggered by the events in New Jersey, and each followed a different path to a similar outcome. The New York Assembly authorized a lottery to raise funds for a college the day after the first New Jersey charter was signed, and the Pennsylvania effort followed quickly upon the college’s 1748 consecration. Both Anglicans and old-light Presbyterians were threatened by what they called the “Jersey College,” since, in their apocalyptic views, a monopoly of collegiate education by New Lights could undermine their churches. However, behind the churches in both cities stood emerging social elites, increasingly aware of the cultural advantage of colleges; if there were to be colleges, these groups felt that they should control them. They were defined by their considerable wealth, in most cases derived originally from commerce but also by positions in government and society that consolidated their status. In New York, many of the key figures were vestrymen in the Anglican Trinity Church—the men who managed the affairs of the Church. In Philadelphia, a party coalesced among supporters of the Proprietor, Thomas Penn, against the Quakers who dominated the local Assembly. Besides holding important official posts, they became trustees of the College of Philadelphia and belonged to other exclusive organizations.19 Finally, elite plans for these colleges did not go uncontested; in each city they were challenged and influenced by individuals with different ideas about education. In the end, though, wealth and social status prevailed.

When the possibility of a New York college arose, Anglicans in the region took the lead.20 Neither the established church in the province nor more than one-seventh of the congregations, they nonetheless regarded the Church of England as an extension of royal government and a natural leader of society. Foremost among them was Samuel Johnson of Connecticut. Following his notorious 1722 conversion, Johnson became a settled minister in Stratford, where he vigorously promoted the Church among hostile Congregationalists. He was responsible for preparing 5 percent of Yale graduates to become Anglican ministers (1725–1748). He also spearheaded Anglican condemnation of the “strange, wild enthusiasm” of the Awakening and regarded the Jersey College as a “fountain of Nonsense.” As a leading colonial intellectual, Benjamin Franklin avidly sought to recruit Johnson to the Philadelphia Academy and published his philosophical treatise, Elementa Philosophica (1752). Prominent Anglicans initially debated the best location for the college. However, the lottery funds were voted by the Assembly rather than the royal governor and consigned to a commission. The location issue was resolved in 1752 when Trinity Church offered to donate a choice piece of real estate on what was then the northern fringe of the city.21

At this juncture a formidable adversary emerged in the person of William Livingston, scion of wealthy upstate landholders, a Yale graduate (1741), and with family ties to the College of New Jersey. He embraced Enlightenment views toward liberty and intellectual progress, and he seemed equally opposed to the presumptuous hegemony of Trinity Church and the Anglican families that dominated its vestry. In 1753 he and his associates launched a journal of opinion, the Independent Reflector, to oppose the planned college. A member of the Lottery Commission himself, Livingston condemned Anglicans for seeking to establish a “Party-College” or the “College of Trinity Church.” As an alternative, he advocated the creation of a public, nondenominational institution. Since the college was funded with public lottery funds, he argued, it should be controlled by the legislature. That body should elect the trustees, who would in turn choose a president. The college should not teach the doctrines of any sect, and students would be free to attend the church of their choice. Anglicans responded that the established church, as they considered themselves, deserved preference in the college. For much of the year this war of words escalated. There was zero likelihood of establishing a nondenominational college governed by the popularly elected legislature, but the anticlerical arguments of the Reflector found considerable sympathy among the majority of non-Anglicans. Thus, as in New Jersey, the controversy shaped the organization of the college.

Behind the scenes, the Anglican elite pressed their advantage. They silenced the Independent Reflector by forcing its printer out of business. They secured the support of the Dutch Reformed Church, traditionally a close ally. Finally, they issued an ultimatum that the college must have an Anglican president and liturgy or else the land would revert to Trinity Church. When this stipulation was accepted by the lottery commission (largely the same individuals), the founding of the college was assured. Samuel Johnson began teaching the first class in July 1754, and several months later lieutenant governor James De Lancey (another ally) signed the charter in the name of the King.

The “College in the Province of New York … in the City of New York in America … named King’s College” conceded several points to its critics. It granted assurances that it would be open to all Christian believers and would not attempt to impose the beliefs of any sect upon its students. These were principles that President Johnson had long upheld and fought for in Connecticut. The college was governed by forty-one trustees who represented the public, though not the elected assembly that Livingston had championed. Seventeen ex-officio members included the royal governor, holders of several public offices, and the senior ministers of Trinity Church and the Dutch Reformed, Presbyterian, French, and Lutheran churches. Twenty-four governors were named in the charter to serve without term, their successors to be chosen by the board. This latter group consisted largely of Trinity vestrymen and their Dutch Reformed allies. They and their successors would hold a firm majority for the life of the college. King’s was thus not the instrument of the Anglican Church that its initial proponents had sought and that its critics had denounced. Only three Anglican clerics sat among the governors—the Archbishop of Canterbury (in absentia), the rector of Trinity Church, and the Anglican president. King’s College instead was owned and operated by the powerful families that patronized Trinity and the Dutch Reformed churches. Moreover, the charter gave the governors powers ordinarily exercised by colonial college presidents, such as choosing the books that would be used and presiding over meetings of the board.22 But why did these gentlemen feel the need to control a college?

A modern answer would be for social reproduction. No less than Massachusetts Puritans a century before, the dominant figures in New York’s hierarchical society hoped a college would perpetuate their community and the social order. By the 1750s, though, cultural ideals had changed. The New York elite envisioned some combination of learning, gentility, virtue, and piety with which to imbue the next generation of lawyers, judges, merchants, and statesmen. Although New York was noted for its philistine preoccupation with business, the spirit of Enlightenment had taken root. Several of King’s founders had amassed enormous libraries, and a few had signed on to Benjamin Franklin’s inchoate philosophical society. William Livingston, among the younger elite (and no less elitist than his foes), had organized a “Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge.” Learning had become an expected adornment of a gentleman. The English model of gentility represented another cultural ideal for social climbers in the provinces, one tangibly exemplified in the aristocracy of the mother country. Familiarity with the classics and literature was deemed essential for forming the manners and taste of a gentleman. “Virtue” was an explicit, if less concrete, outcome expected from the college. This meant producing “truly good men” guided by devotion to duty, selflessness, and righteousness. Samuel Johnson placed foremost the goal of offering a “truly Christian education,” but this was inextricably linked with the inculcation of virtue at King’s and elsewhere. Indeed, the entire college curriculum was infused with moral purpose stemming from this association of piety and virtue. More practically, the college was intended to produce the professionals who would be leaders of society. The legal profession had clearly emerged as the pathway to elite positions in and out of government. Even as the college was forming, New York lawyers established the requirement of a bachelor’s degree to become an apprentice. In the next decade, the King’s College Medical School was organized in an effort to dominate that profession. Thus, there was a direct connection between the cultural ideals the college was expected to cultivate and entry into the upper ranks of New York society. This social reality, more than denominational doctrines or interests, lay behind the bitter controversy over the organization of the college.23

In one sense, the critics’ polemics against the college proved to be self-fulfilling: they so tarnished the enterprise that almost no students from outside Anglican and Dutch Reformed circles chose to attend. However, Anglican hopes were disappointed too. The college failed to provide the ministers needed for Anglican congregations, producing an average of just one per year. Nor did Anglicans from other colonies send their sons to New York. Of the 226 students who matriculated from 1754 to 1776, three-quarters resided within 30 miles of the college, most within walking distance. Fully one-quarter of students were related to governors of the college, and others came from the same social circles. King’s charged the highest tuition of any colonial college and, unlike the College of New Jersey, insisted on 4 years of matriculation to graduate. These factors no doubt helped to depress the graduation rate to near 50 percent.24 Moreover, the governors were unperturbed by this situation. A narrow gateway to the upper ranks of society certainly suited their family interests, but they also regarded it as part of the natural order—as did their counterparts in Philadelphia.

The Proprietary Party in Philadelphia faced a more amiable foe. Self-made and self-educated Benjamin Franklin was exquisitely sensitive to the gradations of social hierarchy that he himself had surmounted but also somewhat skeptical toward colleges, which he had ridiculed as a young man. As an indefatigable proponent of intellectual advancement, Franklin naturally came to address the city’s educational vacuum. His principal concern was to establish an English-language school that would teach modern languages, history, and science, thus preparing students “for learning any Business, Calling or Profession, except such wherein Languages are required.” He broached such a project in 1743, the same year he launched the American Philosophical Society, but found no support. Assured of backing in 1749, he published an extensive Proposal to establish such an academy that would provide all students with a thorough grounding in the English language and, he conceded, instruction in Latin and Greek for those aspiring to “Divinity … Physik [or] Law.” In November, twenty-four trustees gathered to draw up a “Constitution for the Public Academy in the city of Philadelphia” following Franklin’s plan. These self-perpetuating trustees represented the non-Quaker elite of the city: three-quarters were Anglicans; the others were powerful old-side Presbyterians, plus Franklin as president, and one token Quaker. It soon became apparent that the trustees were far more interested in classical than English schooling. Nonetheless, the Academy opened in early 1751 with three instructors responsible for “schools” in Latin and Greek, mathematical subjects, and English. It was described by contemporaries as a “collection of schools.”25

From the outset, the trustees envisioned a higher institution, but the path to creating a college had to be trod carefully.26 When Thomas Penn received Franklin’s Proposal, he initially found it too ambitious, likely to “prevent … application to business,” where only a “good common School education” was needed. But Penn needed supporters on the ground in his struggles with the Quaker-dominated Assembly, and the trustees were his natural allies, soon to be known as the Proprietary Party. He consecrated their work in 1753 by issuing a charter for the Academy, including a Charity School. By then, Francis Alison had been hired and was already teaching collegiate subjects in the “philosophical school.” At this juncture, the Philadelphia project intersected with coeval efforts in New York in the person of William Smith.

A product of Aberdeen University, Smith came to New York in 1751 as a tutor. He quickly inserted himself into the college controversy by publishing a pamphlet supporting the Trinity party, the faction most likely to advance his own situation. He then wrote a more ambitious piece, A General Idea of the College of Mirania (1753). The first American treatise on higher education, it described an educational system for mythical Mirania that embodied Enlightenment values still novel in America. Miranians divided the population into “two grand classes.” Those designed for the learned professions, including the “chief offices of the state,” received thorough training in Latin and some Greek to prepare them for college. The first 3 years of the College of Mirania provided extensive coverage of classical authors, mathematics, contemporary philosophy, and science. A final 2 years were devoted to applying this knowledge, first through polishing speaking and writing skills and finally by studying agriculture (applied science) and history (applied philosophy). All subjects were suffused with natural religion, which provided such a solid base that “revealed religion” in the form of “the general uncontroverted Principles of Christianity” was touched on only once a week on Sunday evenings. As for the rest of the Miranians, they were educated in a Mechanic’s School that is “much like the English School in Philadelphia, first sketched out by the very ingenious and worthy Mr. Franklin.”27 This volume so impressed Franklin and the trustees that Smith was recruited to teach in the philosophical school. But first, Smith returned to England to be ordained as an Anglican priest. His ordination appears to have been a reward for his efforts on behalf of King’s College rather than a reflection of his piety, but he also considered this status appropriate for leading a college. More important, Smith met with Thomas Penn and struck a deal: Penn would support Smith and the establishment of a college, and Smith would work as the Proprietor’s unofficial agent in Philadelphia. In May 1754, Smith was appointed provost; a year later a new charter established the “College, Academy, and Charitable School of Philadelphia, in the Province of Pennsylvania.” The founding of the college was an amicable, consensual affair, but Smith’s new role ensured that this would not be the case for long.

The College of Philadelphia was unique in having neither religious nor government ties. It was led by its assertive provost, who was a political rather than a theological Anglican. He was balanced by vice provost Francis Alison, a committed old-light Presbyterian who shared Smith’s disdain for religious enthusiasm. The college was open to all denominations, as promised in its charter. It considered itself a public institution, despite being governed by a self-perpetuating board of individuals who represented only themselves. Moreover, the trustees exerted tight control over the institution. They created no president, and they reserved to themselves all powers over admissions, appointments, and finance. In this respect, the college was dominated by a social elite as much as King’s, but only some of the outcomes were the same. The college was, by comparison, a thriving, multitiered institution. Around 1760, Smith reported 100 students altogether in the college and Latin and Greek schools, plus an additional 90 students studying English and mathematics in the academy. But like King’s, the college produced few graduates—just 154 from 1757 to the Revolution. More than one-third came from Philadelphia, and many of them were related to the trustees. But the college also drew Anglicans and Presbyterians from the hinterland and surrounding states. Some 20 percent of graduates became ministers, 14 Presbyterian versus 12 Anglican. Some sons of wealthy families attended for several years but felt no need to graduate before pursuing careers.28 Taken as a whole, including the charitable elementary schools for boys and girls, the institution provided substantial education for the region and especially the city, while also serving the purposes of its elite governors. No doubt it could have done more.

By the time the College of Philadelphia was chartered, William Smith had already plunged into provincial politics on behalf of his patron. In anonymous pamphlets, soon unmasked, he attacked the democratic nature of the assembly and advocated greater authority for the proprietor. This offensive included gratuitous slurs of Franklin, who was backing the other side. This struggle grew more acrimonious as additional issues accentuated the polarization. Most important here, Smith’s aggressive Anglican and proprietary positions gave the college a political coloration, which was confirmed when the trustees stood behind him. Franklin was eased out of the board presidency in 1756. He later complained, “Everything to be done in the Academy was privately preconcerted in a cabal…. The Trustees had reaped the full advantage of my head, hands, heart and purse … and when they thought they could do without me they laid me aside.”29 The bitterness of this conflict was exemplified in 1758, when the assembly had Smith jailed for alleged complicity in a libelous attack. The trustees authorized him to teach his students from his confinement, thus thumbing their noses at the assembly. Smith had to go to England to be absolved of the charges, where he was honored with doctorates from the universities of Oxford and Aberdeen. Smith apparently assumed, correctly, that he was protected in his aggressive behavior by the backing of the trustees and proprietor. But the college was not so fortunate. Both Alison and Franklin complained that Smith’s strident Anglicanism was the cause of low enrollments and dwindling participation in its lotteries. As Smith made himself “universally odious,” in Franklin’s words, he could scarcely help but make the college appear partisan.

The irony of this situation was that, aside from its political association, the College of Philadelphia had in Alison and Smith the strongest faculty of any colonial college, save Harvard. Both provost and vice provost were products of the Scottish Enlightenment and introduced the moral philosophy of Francis Hutcheson (discussed below). Smith was the most progressive college leader of the colonial era. His College of Mirania was informed by the midcentury curricular reforms at the University of Aberdeen. In a Postscript to the second edition (1762), he explained that the Mirania plan had been implemented at the College of Philadelphia. Only the first 3 years of the Miranian scheme were taught, but this streamlining of the college course was in itself a significant innovation.30 Smith personally focused on belles lettres and science. A poet himself, he stressed the importance of mastering composition and style in English; he also organized student plays, which were forbidden elsewhere, for public audiences. For science, he became a patron of the famous instrument maker David Rittenhouse and collaborated in gathering data from the celebrated 1769 transit of Venus. The printed course of study for the college was accompanied by a long list of “books recommended for improving the youth” during “private hours,” including “Spectator, Rambler, &c. for the improvement of style and knowledge of life.” Thus, the College of Philadelphia had the potential to provide intellectual leadership for the American colonies, a role that the College of New Jersey would belatedly fill. However, given the predominance of dissenters, few wished to follow a truculent, self-serving Anglican. The hollowness of Smith’s strategy would become apparent when the crisis with Britain arose.31

The founding of the three mid-Atlantic colleges established a pattern that had not been apparent before 1740, when just three dissimilar institutions existed. This pattern, though, did not consist of simple characteristics but rather of a series of appositions that reflected the tacit spread of Enlightenment thinking. First, either formally or in public opinion, they were considered public institutions, but they operated as if owned by particular groups. Ownership was vested in the external boards, or the faculty in the case of William & Mary; but although there could be differences of opinion among these owners, their collective authority was never shaken under colonial rule. Second, the general acceptance of Enlightenment notions of toleration coexisted with a distinct denominational commitment—“toleration with preferment” in the words of historian Jurgen Herbst.32 Thomas Clap’s atavistic resistance—and its ignominious failure—was the exception that proves this rule, as will be seen. Within the colleges, students largely managed to deal with whatever tensions might arise from differing creeds (at least post-Awakening), but contradictions were never entirely resolved among external constituencies, especially where Anglicans were involved. Finally, the spread of Enlightenment doctrines forced the colleges to assimilate the new knowledge into cultural and curricular templates that had been shaped by ancient Greece and Rome. Coming to terms with the American Enlightenment was the most dynamic influence shaping colonial colleges before the Revolution.

ENLIGHTENED COLLEGES

As provincial outposts of the British Empire, the American colonies were slow to appreciate the rich outpouring of ideas from eighteenth-century Britain. When these doctrines were assimilated with dissenting religious traditions, the resulting fusion of ideas has been called the Moderate Enlightenment.33 For new ideas to leap from the pages of books requires individuals to espouse them, a context in which they are meaningful, and institutions in which to embed them. For the colonial colleges, this process first needed the conviction that the new ideas should be taught, then the instructors, books, and materials to teach them. From the 1730s to the 1760s this process gradually accelerated, as trans-Atlantic communication, immigration, and domestic printing all increased. Spearheading this transformation and legitimating other forms of new knowledge was the Newtonian revolution in natural philosophy.

Incorporating Newtonian physics into American classrooms required three pedagogical advances. Explicating the Newtonian universe was perhaps the most basic. Next came the need to demonstrate physical principles through experiments performed with “philosophical apparatus.” Most challenging was to elevate the teaching of mathematics to conic sections and trigonometry and, ultimately, to calculus. The Hollis Professorship of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy created the first such opportunity. Harvard graduate Isaac Greenwood, who was instrumental in obtaining the Hollis gift, studied Newtonian science in London from 1724 to 1726. Upon returning to Boston, he privately offered “An Experimental Course of Mechanical Philosophy” that included “Three Hundred Curious and Useful Experiments” to acquaint his audience “with the Principles of Nature, and the Wonderful Discoveries of the Incomparable Sir Isaac Newton.”34 Greenwood was appointed to the Hollis chair immediately afterward and began teaching the same material to Harvard students (almost 40 years after Newton published the Principia). Essentially a talented popularizer, he presented a general account of Newton’s “Wonderful Discoveries” and employed the philosophical apparatus, also donated by the Hollis family, to demonstrate physical principles in experimental lectures. Telescopes that the college had acquired were employed to teach astronomy. Greenwood upgraded the teaching of mathematics and authored a basic textbook. Dismissed in 1738 for intemperance, he was replaced by John Winthrop, who held the Hollis chair until his death in 1779. Winthrop was easily Colonial America’s foremost professional scientist, continually engaged in observation and inquiry. He published papers in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society and led an expedition to Nova Scotia to observe the 1761 transit of Venus. In the classroom he employed a growing trove of instruments in experimental demonstrations. With Winthrop, Harvard set a standard for teaching natural philosophy that other colleges could only hope to emulate.

Harvard accumulated, through donations from the Hollis family and others, an extensive collection of philosophical apparatus.35 These consisted of assorted balances, pulleys, and inclined planes to demonstrate mechanical principles; air pumps and vessels for creating vacuums; optical instruments to show Newton’s theories of light and colors; as well as microscopes, thermometers, and barometers. Winthrop demonstrated experiments with electricity in the 1740s, before Franklin popularized that subject. For the foremost Newtonian science, astronomy, Harvard acquired a collection of telescopes. Another Hollis gift supplied an orrery—a mechanical model of the solar system that showed the relative movements of the planets. When Harvard’s large collection was destroyed in the 1764 Harvard Hall fire, it was more than replaced by timely donations from 150 different individuals. By that date, the scientific demonstration lecture had become an expected part of the college course. Such apparatus was deemed essential by all the colonial colleges, and they devoted scarce resources to acquire them. However, teaching this subject now required special skills. Creating these positions and finding competent teachers proved more difficult.

At the College of Philadelphia, William Smith was proficient in mathematics and astronomy and later taught natural philosophy to medical students. He employed another math teacher as well. The first professor Samuel Johnson appointed to teach these subjects was a Winthrop student, but he died after 3 years, and his replacement proved inadequate.36 William Small, Jefferson’s mentor at William and Mary, provided scientific instruction for the few years he was present (1758–1762). Later, the college commissioned him to purchase $2,000 of the latest philosophical apparatus. These instruments were used by the future president, Reverend James Madison, a 1772 graduate who became professor of natural philosophy and mathematics in 1773. At Yale, President Clap was an enthusiastic astronomer. After his departure a professorship for natural philosophy was established in 1770, but the incumbents, when the position could be filled, were competent teachers at best. A chair of natural philosophy was a high priority for the College of New Jersey’s new president, John Witherspoon, which was filled in 1771. That same year, Witherspoon purchased the famous Rittenhouse orrery, originally intended for the College of Philadelphia, which then had to wait for a copy to be made. The significance and prestige of Newtonian science altered college teaching by introducing the experimental lecture employing apparatus, creating a demand for specialized professors and establishing the expectation that the curriculum should incorporate new knowledge.

The legacy of John Locke followed a more circuitous route into the curriculum of American colleges. Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding was being read in the colleges by the 1730s, but the problem of reconciling his empiricist conception of knowledge with prevailing theology was largely ignored. In Scotland, however, moralists wrestled with the implications of Locke’s doctrines. The most influential interpretation was offered by Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), a Glasgow professor whose writings on moral philosophy became widely appreciated in the 1740s and 1750s. As a moderate Presbyterian, Hutcheson’s views were compatible with the dissenting American colleges. His moral philosophy epitomized the Moderate Enlightenment’s synthesis of reason and religion, which became the preferred approach in prerevolutionary colleges. Hutcheson posited that the human mind was not a Lockean tabula rasa but rather possessed an inherent moral sense, analogous to human physical senses like touch and smell. A moral sense that distinguished between right and wrong was compatible with revealed and natural religion, while also invoking reason to sharpen these distinctions, especially where the public good was concerned. For subsequent interpreters, this foundation for ethics was “common sense,” and that term came to represent this Scottish approach to moral philosophy that would later predominate in American colleges. For Presbyterians on both sides of the Atlantic, it provided a cogent marriage of reason and religion.

Hutcheson’s moral philosophy was first propounded in America by Francis Alison at the College of Philadelphia, who led students through a literal explication of his writings.37 Philadelphia students began moral philosophy in the middle of the second year and continued it into the first term of the third (final) year. In addition to basic ethical issues, Alison later included Hutcheson’s views on natural rights and social questions. Hutcheson drew upon the “Whig canon” in justifying natural rights, balanced government, and the right of resistance to tyranny; Alison, too, taught these doctrines in his classroom and later invoked them for the patriot cause. More influential in elevating moral philosophy to a central role in the curriculum and Republican ideology was John Witherspoon, the Scot who became president of the College of New Jersey in 1768. Witherspoon lectured the seniors on moral philosophy, thereby enshrining it as a “capstone” of the college course. He taught the basic doctrines of Hutcheson but was considerably more eclectic. He included recent enlightened thinkers, such as David Hume, if only to refute them; and he encouraged students to read current authors in the college library, often in the volumes that he had brought from Scotland. In Witherspoon’s worldview, moral philosophy was as much a part of nature as Newtonian science. He looked forward to “a time … when men, treating moral philosophy as Newton and his successors have done natural, may arrive at greater precision.”38 A historian of the American Enlightenment judged that Witherspoon’s “theology, philosophy, and politics were exactly appropriate to their time and place”; and his introduction of the Common Sense philosophy, in particular, was “the first promulgation of the principles that were to rule American college teaching for almost a century.”39

The origins of the political philosophy that underpinned the Revolution are more diffuse. Historian Bernard Bailyn has explained the intellectual roots of the American Revolution as the fusion in “the decade after 1763, [of] long popular, though hitherto inconclusive ideas about the world and America’s place in it … into a comprehensive view, unique in its moral and intellectual appeal.” Sometimes called the Whig canon, it conflated and drew what seemed relevant from three congeries of thought: first, notions of natural rights and social compact drawn from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century political theorists; second, the concept of balanced government drawn from historical examples of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy; and third, belief in the inherent liberties of Englishmen and the English constitution, shaped by that nation’s tumultuous history. American colleges taught some of these constituent materials throughout the eighteenth century, added more enlightened authors by the 1760s, and allowed or encouraged students by the 1770s to explore this ideology on their own. Thus, while the colleges had little direct input to the Whig canon, they provided a milieu in which its multiple components could reinforce one another.40

Political theorists who rationalized theories of natural rights and the consent of the governed were read sparingly in the curriculum. Locke’s Two Treatises on Civil Government was not used before the prerevolutionary years and then was only recommended. The widest arrays of these writings were recommended at the colleges of New Jersey and Philadelphia. Witherspoon and Smith explicitly advocated outside reading as an essential component of education and provided lists of titles that students should peruse for their own “improvement.” In addition, Hutcheson’s Moral Philosophy reinforced the Whig canon where it was taught. Undoubtedly, political theory became more pertinent as the crisis with Britain deepened after 1765. In the readings pursued on their own, students often favored histories, including the English saga of opposition to government tyranny from the Commonwealth to the Glorious Revolution. At Harvard, where there is some documentation, students read a broad spectrum of modern histories. Typically for the period, such works were written from inherently moral perspectives.41 This was even truer of the Latin and Greek classics that had been the staple of the college curriculum since Henry Dunster.

A large part of this literature is concerned with political themes. The Greek states of the fifth century BCE, were preoccupied with wars and issues of governance; the most read Latin writers dated from the two centuries after 50 BCE that witnessed the fall of the Republic and the vicissitudes of early Empire. After 1750 college assignments included greater coverage of historical works that directly addressed such issues. Caesar’s Commentaries and the histories of Sallust and Tacitus were now added to Cicero’s political orations; in Greek, the historical writings of Herodotus, Thucydides, and Plutarch were now read. These writings were filled with republicanism, civic morality, and observations on government, which became more relevant as the crisis deepened.42 College students in these years appeared to embrace classical studies enthusiastically, and this interest laid a foundation for the doctrine of republicanism that dominated the new nation from the time of the Revolution. Students in the enlightened colleges of the 1760s and 1770s found immediate relevance in the ancients even as they sought to assimilate the new learning of their own century.

The intellectual currents of the eighteenth century favored the increasing attraction of belles lettres in prerevolutionary colleges. The term encompasses work in the English language—literature as well as the perfecting of writing and speaking that was also called rhetoric. Literature included imaginative writings, particularly drama, history, and essays. Especially popular were the writings of Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in The Spectator, a short-lived literary journal (1711–1714) that was widely reprinted. The Spectator was admired for its literary style, for popularizing basic Enlightenment ideas, and for applying them to everyday life. William Smith reflected this perfectly when he recommended students read it for self-improvement. Smith was an early advocate of belles lettres, making command of the English language a goal of both the College of Mirania and the College of Philadelphia. Belles lettres thus connoted both the cultivation of useful skills, particularly public speaking, and assimilation of the sophisticated culture of the mother country. These objectives were so attractive to students that they pursued them independently through the organization of literary societies (discussed below). Harvard students showed increasing interest in plays, poems, and novels, and they organized a drama club in 1758. The restocked Harvard library after the Harvard Hall fire contained ample works of contemporary literature, and in 1771 Harvard created a chair in rhetoric and oratory.43

Yale students were late in manifesting an interest in politics but took a lively interest in belles lettres. These interests were encouraged by two tutors, future president Timothy Dwight (Y. 1769) and the poet John Trumbull (Y. 1767). They challenged the prevailing view that “English poetry and the belles-lettres were … folly, nonsense and an idle waste of time.” Students responded by petitioning the Yale Corporation to allow Dwight to offer special instruction in rhetoric and belles lettres.44 Trumbull produced a remarkable satire of the traditional Yale student, “The Progress of Dulness or the Rare Adventures of Tom Brainless.” The protagonist is a country boy prepared and sent to college by his parents. Incapable of benefiting from the experience, he

Read ancient authors o’er in vain,

Nor taste one beauty they contain.

Four years at college doz’d away

In sleep, and slothfulness and play.

Tom graduates despite these failings and, unfitted for anything else, becomes a teacher:

He tries, with ease and unconcern,

To teach what ne’er himself could learn.

Tom’s natural progression is to become a soporific country preacher, who

On Sunday, in his best array,

Deals forth the dullness of the day.45

Trumbull’s mockery of what had hitherto been the modal Yale student reveals how Enlightenment culture had displaced orthodox Calvinism in the late-colonial colleges.

I see

Freedom’s established reign; cities, and men,

Numerous as sands upon the ocean shore,

And empires rising where the sun descends!——

The Ohio soon shall glide by many a town

Of note; and where the Mississippi stream

By forests shaded, now runs weeping on,

Nations shall grow, and states not less in fame

Than Greece and Rome of old!

Originally justified to polish the speaking skills of ministers and statesmen, belles lettres transcended that role, capturing the imagination and enthusiasm of collegians to craft their own indigenous literature.46

★ ★ ★

Finally, medical education provides an entirely different example of the impact of trans-Atlantic learning on American colleges. Interest in establishing medical schools arose among physicians in New York and Philadelphia in the 1760s. In both cases, impetus came from recent medical graduates of Edinburgh University. The medical school in Edinburgh had been organized only in 1726, but it quickly became renowned for its excellent instruction and the favored locus for American students. Few university-trained MDs practiced in colonial North America, and almost all were located in the largest cities. They competed there against practitioners with various levels of training and even more varied approaches to healing. University-educated MDs possessed higher status and wealthier patients—as well as an inflated confidence in their own medical acumen.47 Thus, young men with European training seized the initiative to upgrade medical instruction in American cities.

William Shippen Jr. and John Morgan were sons of elite Philadelphia families who took MDs at Edinburgh in 1762 and 1763, respectively. Shippen returned to Philadelphia and began offering private lectures in anatomy. Morgan capped his education with a grand tour of the Continent, where he discussed medicine with famous physicians and had audiences with both the Pope and Voltaire! He returned to Philadelphia with a detailed plan to establish medical education in conjunction with his alma mater, the College of Philadelphia. Morgan’s social standing eased acceptance of his plan. He brought letters of support from Franklin, Thomas Penn, and several college trustees. In 1765 he was appointed Professor of the Theory and Practice of Physick. Shortly thereafter, Shippen was given a similar appointment in Anatomy and Surgery. Other appointments followed of physicians with similar backgrounds, including Edinburgh graduate Benjamin Rush, who later became the most authoritative figure in early American medicine. By 1769 a full medical faculty of five was offering courses—all Edinburgh graduates. Nor was the medical school a financial burden to the college; the professors’ only compensation came from student fees.48

The announcement of the medical appointments in Philadelphia galvanized a group of university-trained physicians in New York to follow this “laudable Example.” They included both newly minted and established MDs. In 1767 their proposal to establish six chairs in a medical school was accepted by the King’s College trustees. These professorships—anatomy, surgery, theory and practice of medicine, chemistry, materia medica (or pharmacy), and obstetrics—paralleled the course at Edinburgh and (its model) the University of Leyden.49 At both King’s and Philadelphia, the new professors had an elevated conception of their mission and, as a result, made degrees difficult to obtain. The first degree was a bachelor of medicine, which required a complete course of lectures, general examination, knowledge of Latin and natural philosophy, and apprenticeship—in at least 3 years. The MD required another round of courses and examinations, plus publication and public defense of a “treatise.” Ten or twelve students earned BM degrees from King’s and two of them proceeded to an MD; at Philadelphia, thirty-one students took the first degree and five, the second. At King’s the vitality of the medical school waned after the first few classes, but attendance at Philadelphia topped thirty students before the Revolution forced a suspension of classes.50

Physicians in the eighteenth century “became stratified primarily by the amount and nature of education” they received; however, patients “rarely benefited … in proportion to the amount of training of the physician.”51 In fact, medical science made little progress during the Age of Enlightenment. Physicians, whether practitioners or professors, made diagnoses on the basis of superficial symptoms, like fever, and were hopelessly muddled regarding causation and cures. These failures, and fanciful theories of disease, made it difficult for physicians to learn from their own cases. The single area in which education and training might improve results was surgery, which was still severely constrained by ignorance of infection and anesthesia. Under these conditions, perhaps it is understandable that neophyte, European-trained doctors were overconfident about the efficacy of medical arts. This was the case with John Morgan and especially Benjamin Rush, a zealous “bleeder” who obstinately defended his convictions and was continually engaged in controversy. But the desire to introduce the “unequalled Lustre” of European medical education no doubt increased enthusiasm for medical schools. Sincerely trusting in their own knowledge, they hoped to raise the standard of medical practice and their own standing as well. Rush noted that his professorial appointment in 1769 “made my name familiar to the public ear … [and] was likewise an immediate source of some revenue.”52 Beyond serving their professors, the schools met with limited success. They raised the bar too high for new MDs and thus constrained access to what little knowledge the professors could offer. And the public never shared their own confidence in their art. Consequently, control over medical licensing was generally withheld from educated doctors. This tension between medical schools, the wider medical profession, and the licensing of doctors would bedevil the field for another century.

COLLEGE ENTHUSIASM, 1760–1775

When Reverend Ezra Stiles, future president of Yale, learned of the chartering of Dartmouth College, he noted that three more colleges were in the planning stage in Georgia, South Carolina, and his own city of Newport, Rhode Island: “College Enthusiasm!” he wrote in his diary.53 Stiles was reacting to a growing public interest in colleges, particularly in places where they were lacking. This same concern had already brought existing colonial colleges under increased public scrutiny. Internal and external pressures were pushing them toward reform and modernization. The spread of Enlightenment thinking was only part of the changing environment. Expectations of religious toleration were now paramount among these church-linked institutions. More immediate, the colonial elites that composed their governing bodies were sensitive to changing conditions in colonial society. In the 15 years before the Revolution, the first six colonial colleges were prodded to adapt to rapidly changing conditions, while “college enthusiasm” produced three additional institutions. The waning of the old order was most vigorously resisted at Yale.

Thomas Clap had spent much of the 1740s opposing the New Lights of the Awakening, but in the 1750s his regime was challenged from the opposite direction—by the spreading acceptance of Enlightenment views.54 Clap upheld contrary convictions: he rejected religious toleration within the college, censored library holdings, and argued that colleges are primarily for training ministers. This fundamental divergence lay at the heart of the Yale controversy, but it was grounded in the fractured religious polity of Connecticut and further confounded by the issue of the colonial government’s authority over the college. The Old Lights, who remained a powerful force in Connecticut politics, represented the moderate wing of the Congregational churches, increasingly open to toleration and reason; and these views were further supported by a growing Anglican presence. Clap soon rejected his former allies and embraced the New Lights. But they, too, had changed and were now led by New Divinity preachers—college-educated zealots inspired by Jonathan Edwards and Samuel Hopkins. The New Divinity energized Yale’s dwindling number of ministerial candidates. However, their approach proved too extreme—and esoteric—for most congregations. So here, too, Yale’s sectarian emphasis was out of tune with much of Connecticut society.55

The campaign against Clap began in earnest in 1755 with the publication of a critical pamphlet. The not very anonymous author was Benjamin Gale (Y. 1733), a prominent physician and scientist, member of the Assembly, and staunch secularist. He was closely associated with his father-in-law, Reverend Jared Eliot, the foremost critic of Clap on the Yale Corporation.56 Gale’s pamphlet first addressed Yale’s finances, showing that the college had no need of the annual £100 subsidy it received from the colony. He then attacked Clap’s attempts to force students to attend church services within the college and the proposed appointment of a professor of divinity—steps he called establishing an “Ecclesiastical Society.” Gale found no justification in the statutes for a college church. Yale College was established by the Assembly as a secular institution for the instruction of youth, “either in Divinity, Law, Physick, or some other Profession.” The Assembly, furthermore, was the “Overseer” responsible for the college. Gale’s argument echoed Livingston’s campaign for “public” governance of King’s College, but in this case Clap was actually instituting the kind of denominational hegemony that Livingston had hypothetically imagined. The political question was whether or not the Assembly, as Overseers, would appoint a committee of visitation that would almost certainly undo Clap’s policies.

In the event, the Assembly withdrew Yale’s annual grant but went no further. Clap then proceeded to fulfill his plan. He raised funds for a professorship of divinity and brought in Naphtali Daggett (Y. 1748), who was duly installed after a trial period and intensive interrogation (1756). Despite Yale’s limited faculty, Dagget’s job was to preach, not teach. Yale still had no professors to assist the president in teaching substantive subjects. Clap also succeeded in creating a separate church within the college, over the opposition of Jared Eliot and several other trustees. The president had now alienated his former supporters and at this point turned to the New Light/New Divinity Party for support. He had succeeded in establishing a sectarian college but one that represented only a minority of Connecticut Christians. More ominous, opposition to Clap and his rule, led by Gale, continued to build throughout the province.

Despite the hyperbole over religious intolerance, students seemed little affected. If anything, their behavior reflected the sinking reputation of the president. College discipline degenerated in rising absenteeism, wanton vandalism, and open defiance of Clap. Despite repeated requests to intervene, the Assembly was reluctant—either to confront Clap or become embroiled in religious controversy or both. Finally, in 1763, a petition from leading citizens could not be ignored: It complained of the “arbitrariness and autocracy of the President, the multiplicity and injustice of the laws … and the unrest of the students”; and it requested that the Assembly review the college laws and send a visitation committee.57 Both sides were invited to state their cases to the Assembly. Before a hall packed with spectators, Clap presented a masterful defense. Whereas his opponents assumed that the Assembly was the legal founder of the college and thus its rightful overseer, Clap provided an alternative history: the school was begun a year before the 1701 charter by a meeting of Connecticut ministers, who pledged their own books to found the college. This story was elaborated with legal citations to form an apparently convincing case. Clap further alleged that the charges of the petitioners and the (supposedly exaggerated) disorders in the college were instigated by his long-standing enemies. When the new-light-leaning Assembly declined to intervene, Clap emerged triumphant. Moreover, his dubious account of Yale’s founding was long held to establish the private nature of the college.58 But none of this lessened his problems in New Haven.

Disorder in the college continued to escalate, finally reaching open rebellion.59 In 1766 nearly all the students signed a petition of grievances to the corporation. When the corporation declined to act, they boycotted classes and became violent. The tutors were forced not only to resign but to flee New Haven. The corporation declared an early spring vacation, but when the college reopened (with no tutors), few students returned. Faced with the ruin of the college, Clap had no choice but to resign. The rest of the school year was effectively canceled, and Clap presided over a subdued commencement as his last act. Perhaps the most consequential student rebellion before the 1960s, student resistance had succeeded where Clap’s many enemies had failed. But compared with the growing vitality of other colonial colleges, Yale for long was unable to keep pace.

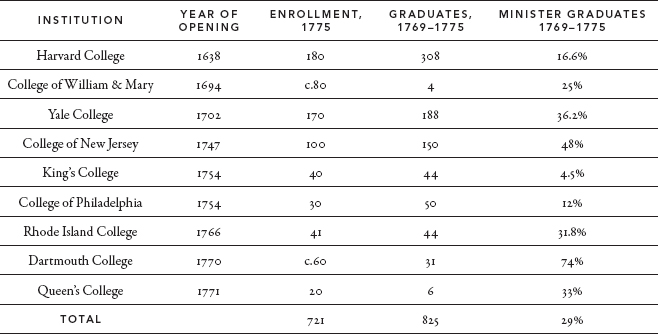

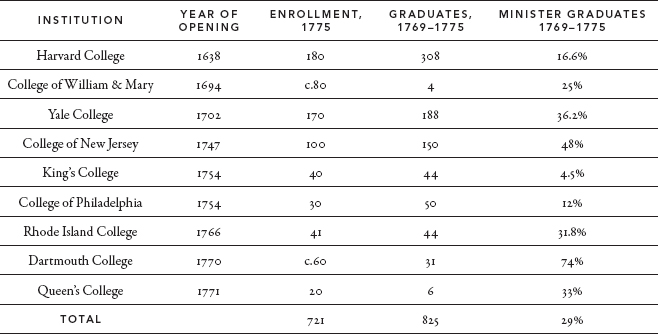

Unable to find a suitable replacement who would accept the position, the corporation named Daggett acting president. The scholarly Daggett had aptitude neither for administration nor for governing students, and the Corporation signaled their lack of confidence in him by closely managing college affairs, choosing the tutors, for example. Daggett, unlike his predecessor, made few enemies, and the college slowly recovered. But he had previously taught only divinity, and even as the college’s sole professor did not lecture to students. Not until 1770 was an undistinguished professor of math and natural philosophy appointed to cover Clap’s subjects. The college did manage to appoint effective tutors in these years (Dwight and Trumbull), who seem to have carried the instructional load. Nonetheless, the college benefited from a geographical monopoly.60 Throughout the turmoil of the Clap years, it enrolled around 170 students. Attendance fell to almost half that number during and after the collapse but gradually rose to the previous level by the Revolution. By then, students were expecting more from their education (see below). Confronted with increasing student disorder, Daggett resigned the presidency in 1777, although not his professorship. Yale was the second largest colonial college, at times exceeding Harvard in enrollment (table 1), and was reasonably well furnished; but at best Yale offered perfunctory pedagogy and contributed nothing to learning.

Harvard prospered under the placid presidency of Edward Holyoke (1737–1769) from before the Awakening until the pre-Revolution turmoil. Ezra Stiles, who rated all the college presidents he had known, described Holyoke as having “a noble commanding presence … [and] great Dignity”; “Yet not of great erudition.” Holyoke’s own judgment on his career was more negative: “if any man wishes to be humbled and mortified, let him become President of Harvard College.”61 He never explained if this statement reflected his treatment by students or Overseers, but the progressive changes in the college during his tenure largely originated with the latter.

Harvard still retained much of the arts course of a Puritan college when Holyoke assumed the presidency, but it also had unique strengths. The two Hollis professorships ensured that college teaching would reflect up-to-date scientific knowledge and moderate interpretations of religious doctrines. A large and inventive student body found ways to pursue their intellectual interests, as will be seen in the next section. And the Board of Overseers by the 1750s contained “unusually intelligent and cultivated gentlemen” who were sensitive to educational trends. Still, a later president observed that the college adjusted “tardily” to the “impulses given to science and literature in England, during the reign of Queen Anne”; and “it was not until after the middle of the eighteenth century, that effectual improvements were introduced.”62 Beginning in 1754 the Overseers voiced concern for student attainments in oratory and classical learning. In a series of steps that were often resisted in the college, they established public exhibitions of forensic disputations—the kind of public speaking valued by gentlemen like themselves, and by students too. New prizes were awarded based on merit. It took until 1766 for these practices to become the law of the college, but then created an eighteenth-century version of accountability.63 In the meantime, the Overseers began to reorganize instruction.

In a prescient move, the Overseers resolved around 1760 to create more professorships for the college by finding donors of endowments. They obtained six such pledges, all in wills. Only one was realized immediately, the Thomas Hancock Professorship of Hebrew and Oriental Languages. It was awarded in 1765 to Thomas Sewell, an accomplished linguist and instructor in Hebrew, who was rewarded for proposing a plan to upgrade the teaching of classical languages. A second appointment that year installed Edward Wigglesworth Jr. to succeed his father as Hollis professor of divinity. He was a biblical scholar but, unlike his father, not an ordained minister. He also broke precedent by being eager to teach in the college. At this same time, the Overseers decided that “tutors should function differently than they do now.” A reorganization the following year assigned each tutor to teach a single subject to each class, rather than teaching all subjects to a single class. The four tutors were made responsible for Latin, Greek, philosophy (logic, ethics, metaphysics), and science (math, astronomy, natural philosophy). Each also served like a homeroom teacher, providing instruction to a single class in English language skills (elocution, rhetoric, and composition). With these reforms Harvard formalized a faculty that distinguished between introductory and advanced instruction—a structure that could accommodate both basic instruction and some advanced learning.64

★ ★ ★

The three Anglican colleges all had direct or indirect ties with England, although these relationships differed from New York to Philadelphia to Virginia. These colleges also wrestled with issues of curriculum and institutional control. Despite the difficulties in relations with England in the wake of the Stamp Act crisis, Anglicans aggressively upheld the interests of their colleges. Their confidence stemmed from a superficial perception of growing strength.65 Culturally, as the upper classes of colonial cities increased in wealth and sophistication, they became more Anglicized in material goods, social conventions, intellectual culture, and church membership. Politically, the notion of a cosmopolitan British Empire was more appealing than parochial colonial assemblies. And although the Anglican Church in America was relatively weak and fragmented, its leaders usually occupied the heights of the colonial social hierarchy. They believed the Church of England deserved a privileged position in British Imperial society, and for them the colleges were strategic institutions.

At Philadelphia, Provost William Smith fully shared the outlook of the mostly Anglican Trustees, whose interests were aligned with those of Proprietor Thomas Penn. The college was officially nonsectarian and included old light Presbyterians among both faculty and trustees. The issue of religious balance was nonetheless delicate. When concerns were raised about Anglican domination in 1764, the trustees issued a declaration that the existing denominational representation in the college would be permanent. This step assured Anglican advantage but not for proselytizing. Smith was a virtual Deist, who dismissed theological doctrines as “Rubbish.” Philadelphia was by far the most enlightened college, and that in itself may have lured students toward the lenient tenets of the Anglican Church.66

By the end of the 1760s William Smith was at the pinnacle of his social and intellectual eminence in America’s largest and wealthiest city. He was the leading figure in the Anglican Church and the College, an author, scientist, and office-holder in numerous organizations. Typically, he staged public student dramatic presentations—the first being Alfred, A Masque, a glorification of Alfred the Great that concluded with the singing of Rule Britannia. When the American Philosophical Society was resuscitated in 1768, Smith became its permanent secretary. Although he could not match the social and financial status of the proprietary gentry, he was part of the same social circles, and so was the college. Besides attracting the sons of the non-Quaker gentry, the college drew students from large landholders in Maryland and the South. Compared with other colleges, its students paid high fees, had a low rate of graduation, and were notably youthful. Wealthy parents tended to provide thorough and early educational preparation, creating the ironic situation that one of the youngest bodies of students was taught the most advanced curriculum. Graduation was not a high priority for students whose careers would be determined by families, not credentials. The college was financed primarily through fund-raising—another art that William Smith mastered. Both the College of Philadelphia and its Provost were ideally adapted to the Anglophile social and cultural milieu that would soon be challenged by the Revolution.67