Woke with a strange feeling. Quiet and deep. Difficult to describe. More intense than I’ve known with any job before.

Bracing myself to meet a massive force…

But, as always with these things, once you actually get to the reality of work, the practicality of it, the ordinariness, a different energy takes over.

Our rehearsal room is on the third floor of the new The Other Place building, and called the Gatsby Room (after Susie Sainsbury’s Gatsby Charity): a huge, open, wooden chamber, with tall windows overlooking the Bancroft Gardens and river.

This week is being referred to as an ‘extra week’. I requested it personally – to give myself a little more time. (There’s never enough for the big roles.) This is, in fact, the next phase of my rehearsal process, which began over a year ago. The main body of the company don’t join till next week, but certain actors will come in for sessions with Greg and me over the following few days.

It’s also a chance to start setting up some crucial research work, like a meeting between me and a psychologist, to analyse Lear’s ‘madness’. This needs to be as soon as possible. Our company manager, Linda Fitzpatrick, set off to do some research of her own, and find out who the right person might be.

Then the first actor came in, thank God. Graham Turner, who’s playing the Fool. I felt an instant rapport with him. He has great warmth, and straightaway mentioned the love which the Fool and Lear have to share. And he was very open to Greg’s suggestion that the Fool needs to be a professional entertainer as well as a truth-teller. I was also delighted to notice that he has something of Michael Williams’ comic-mask face.

Good, important discovery. In their first scene together (Act One, Scene Four) the reason why the Fool can get away with his merciless jokes about Lear, and his idiocy in giving away the kingdom, is because nothing bad has happened yet. The Fool’s banter is just this week’s satirical material (an episode of Have I Got News for You), and next week it’ll be something else. So Lear can laugh along with the piss-take of him. It’s what the Fool does, it’s what he’s ‘alllicensed’ to do. But then trouble does break out later in the same scene – the row with Goneril – and suddenly the Fool’s criticism of Lear is revealed to be prophetic.

Afternoon. A session with David Troughton (Gloucester) and Tony Byrne (Kent). God, it’s good to have these two RSC heavyweights at my side in this. An interesting discussion. Does Lear consult his top lords on policy decisions? Does he hold council meetings? I can’t quite picture these. Can’t see him taking advice from anyone.

Tuesday 21 June

Before rehearsals, back to the Arden Medical Centre. Syringing my ears didn’t help, and the weird echo in my head is more and more distracting. Today the doctor thought there might be a little liquid trapped behind my left eardrum, and prescribed some nose drops. Said if it didn’t clear up in a week, we’d have to think about going to an ENT specialist.

Morning. First, a session with Nia Gwynne, playing Goneril. Good to see her again – we developed a great chemistry as Falstaff and Doll Tearsheet in Henry IV Part II. Today she said she was keen to approach Goneril from the character’s own point of view, and not as one of the Wicked Sisters. I couldn’t agree more – it’s a big danger in the play.

Then a session with Mike Ashcroft (movement director) and Bret Yount (fight director), to talk about Lear’s hundred knights, who become such a bone of contention between him and his daughters after he abdicates. We’re lucky in that we’re actually going to be able to represent them more fully than most productions, because the RSC is employing twenty-four supernumeraries (or extras, as they used to be called) to fill out the stage for those scenes. But what type of men should they be? As it happens, Greg received a letter from a Shakespeare scholar recently, who said he was looking forward to our production, but had a request: ‘Please don’t show any evidence of Lear’s knights being riotous… It wrongly dignifies Goneril.’

Well… it’s a question of propaganda. Who should the audience believe? Lear claims that his followers are a team of noble and dutiful chaps (‘men of choice and rarest parts’), while Goneril is describing a gang of out-of-control squaddies (‘men so disordered, so debauched and bold’). But as Nia said earlier, it’s so much more interesting to take her point of view, to, yes, ‘dignify’ her – and that means showing the knights as she sees them. Lear is in retirement now, and having a wild old time – hunting and boozing with his buddies. All well and good, unless they’re staying in your home, and you’re having to cope with the mess and chaos they cause.

We decide to make them as wild and unruly as possible. And when the row erupts between Lear and Goneril, they should, before they leave, trash the joint. Stage management make notes about the tables and benches having to withstand being overturned.

Also, a brief discussion about Lear carrying on Cordelia at the end, for ‘Howl, howl, howl’, when she’s dead. This is going to be impossible for me – with my buggered arm. Another solution will have to be found. Greg says quietly, without anger, ‘But it’s one of the most iconic images in Shakespeare…!’

Afternoon. Solus with Greg. We read, paraphrase, and discuss.

Describing Lear’s temper, Greg put it well: ‘He can go from A to Z without the intervening alphabet.’

Big breakthrough, in Act One, Scene Four (in fact, the hundred knights scene again). I’ve been confused by Lear’s line:

O, most small fault,

How ugly didst thou in Cordelia show!

But if you think of the word ‘show’ as being ‘seem’ – and we could easily change it – things becomes clearer: Lear is acknowledging that he made a mistake in his savage treatment of Cordelia.

Which links to his line to the Fool in the next scene, ‘I did her wrong’, which has also been puzzling me.

It’s now apparent that Lear realises his mistake much, much earlier in the play than I thought.

Bedtime. I put in the new nasal drops, sniffed them down, then said to Greg:

‘This is ridiculous. The doctor said I should wait a week to see if this stuff helps my hearing. I can’t wait a week – we’re doing King Lear, for God’s sake! This is so typical. We’re a world-class theatre company with the medical back-up of a small country town. In every Shakespeare play, there are fights, dances, our voices are pushed to the limits… we need physios and specialists like dancers and singers have…!’

(This has been my argument with the RSC ever since I joined in 1982, and, soon after, snapped my Achilles tendon.)

Greg turned away impatiently: he’ll tolerate no criticism of his beloved company.

I said, ‘I should go and see an ENT specialist as soon as possible. I shouldn’t wait a week to see if these little nose drops work.’

Wednesday 22 June

A one-to-one with Ciss Berry.

She’d not seen these new rehearsal rooms yet. Stopped in the doorway, blinking with displeasure: ‘Does it have to be this big?!’

‘Uhm, yes,’ I said; ‘It has to be able to take the footprint of the main stage, and leave space all around.’

‘Huh!’ she said, and moved to the work table, her stick thumping.

And so we began. She was being a grumpy old lady, and was going to help me become a grumpy old man.

And indeed, she had some fine insights.

• Lear’s loneliness. ‘In a position of supreme power, he’s on his own. More susceptible to fears. It makes him think fast and rage fast. He can only see things in his way. He’s convinced his power will keep going. He thinks he can see everything, all the possibilities in people, but he’s not seeing clearly. He’ll learn to do this during the play.’

• Lear’s humour. She points to a line in his first speech, when he says that he’ll ‘crawl toward death’. It makes her chuckle: ‘It will happen, it will fucking happen!’

I’m no longer sure if she’s just talking about Lear, but only a ninety-year-old could help me see that line as funny.

Thursday 23 June

Afternoon. To Solihull Hospital to see an ENT specialist, Mr H. (Our new Head of Voice, Kate Godfrey, had speedily arranged this appointment.) He confirmed there might be liquid trapped behind the eardrum. Said there was a simple procedure, a little incision, which could cure it instantly: ‘We do it on children who’ve been in the pool too long.’ I said, ‘Good, let’s do it now.’ He said no – he’d have to do some tests first. Prescribed stronger nasal drops.

(They don’t get it, these ‘civvy’ doctors, they just don’t get it. We need theatre medicine-men. If there’s a simple procedure, just do it. We’re in rehearsals, there’s no time for tests.)

Friday 24 June

Jesus Christ.

Yesterday, there was a referendum. Should Britain remain in the EU or leave? (Greg and I both voted Remain.) Today, not only the result, but some results of the result:

• Britain will leave the EU.

• The Prime Minister, David Cameron, resigns.

• Calls for the Leader of the Opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, to resign.

• Scotland, who wanted to remain, intends to hold another referendum on independence.

• The pound crashes to a thirty-year low.

When we were leaving the house, Greg said, ‘Right, well, let’s go and rehearse a play about the catastrophic consequences of a country tearing itself apart.’

In the morning, another solus with Greg.

As we sat down, I said, ‘I’ve got something I’d like to talk about.’

(We’re both trying, scrupulously, to observe our principal rule when we do a show together: Only discuss work when at work.)

‘You go first,’ I said.

‘Well, it’s this idea of homeless people being in the action…’

I nodded, thinking back to the beggar woman in Rome.

‘… It’s the other side to life in the court, it’s the side that Edgar is forced into when he becomes Poor Tom, the side that Gloucester has to join when he’s blinded, and then Lear too, when he goes mad. So I think we should show the homeless at various points throughout the first half, and then of course in the storm…’

‘Good,’ I said, ‘That sounds good.’

‘So you’d be okay doing the “poor naked wretches” speech with them actually around you?’

I hesitated. ‘You mean… them naked?’

‘No, no, not naked.’

‘Oh. Good. Otherwise, I could be a bit upstaged.’

‘You won’t be.’

‘Good. Then it’s a terrific idea – let’s try it.’

‘Good,’ echoed Greg. ‘Your turn.’

‘Well, I was wondering if, in the mad scene, Lear turns into the Fool. It sort of explains the Fool’s disappearance from the play. It’s because Lear has become the Fool.’

Greg leaned forward. ‘But it’s what Donald Sinden did in that production… when was it?… mid-seventies?… with Michael Williams playing the Fool for the second time. Sinden did the mad scene half-dressed as Williams.’

‘I didn’t know that,’ I said lightly. (God, I hate Greg’s encyclopedic knowledge of RSC productions.) ‘But it doesn’t matter. I have a special right to turn into the Fool. Sorry, that sounds arrogant, but… I don’t mean it to be… but ever since we decided we were definitely doing Lear, I’ve had this… secret, private idea… that I should play the mad scene like I played the Fool.’

Greg frowned. ‘How exactly?’

‘Very simply. If Graham could wear a red nose…’

‘Like you did.’

‘Exactly. And…’

Greg interrupted: ‘Look, I’ve said this before – I can’t, I won’t ask Graham to play the Fool like you did!’ He softened his tone. ‘Anyway, red noses aren’t really part of our world, are they? Our pagan world.’

‘No, but if it was something less manufactured, something more natural.’

‘Like what?’

‘Like… I don’t know… a tomato.’

‘A tomato?’

‘Yes, if in the dinner scene, after the hunt, if there were tomatoes on the table, and if Graham put one on his nose, sort of squashed it on… we can do some kind of cheat, some kind of fastening…’

Greg’s frown grew. ‘And then – ?’

‘And then when I come on in the mad scene, it can be with…’

‘A squashed tomato on your nose?’

‘Well, yes… sort of… as a little echo of the red no–’

I went silent. We both did. Then Greg said:

‘Let’s think about it, shall we?’

In the afternoon, back to Solihull Hospital, for ear tests. A strange procedure, with me wearing earphones, and a technician playing short sounds at different low levels, asking me to press a button whenever I hear one, or even think I hear it.

Sunday 26 June

After lunch, phone calls to South Africa.

Joan said how much she was missing Verne. How lonely she felt.

Randall reported that Yvette has taken a sharp decline. She isn’t always compos mentis, can’t be heard or understood, shakes so much she can’t do anything for herself, stays in bed all the time. Randall said her specialist was coming round tomorrow for a big family meeting.

These calls depressed me badly. Just sat staring out at the grey drizzle and chill of this summer afternoon.

Meanwhile, tomorrow is the final and most vital phase of my rehearsal journey. Or, to put it another way, it’s…

…Week One of rehearsals proper (we have seven weeks in all), with the full company.

It’s the strangest first day I’ve ever had.

Because of my hearing.

I’m in a dream-like place, meeting new people, going through the motions of beginning…

Then Greg stands up to make his opening speech, and I force myself to focus, jotting notes.

Greg begins with a head-on confrontation: ‘Charles Lamb advised people to keep re-reading King Lear and avoid its staged travesties. Well, I’m here to tell you that the point of these rehearsals will be – precisely – to avoid staging any kind of travesty!’

Then he says, ‘Lear is elemental. If Hamlet is cold, if Othello is heat, if Macbeth is darkness, then Lear is STORM.’ He looks round the group. ‘Is Lear a story that ultimately makes moral sense? Is it a story of learning and redemption? Or is it something else altogether? Because the play ends not with order or disorder, but with a strange, profound unease.’

He goes on: ‘Samuel Beckett is sometimes mentioned in the same breath as Lear. When Beckett wrote Waiting for Godot in 1948, it was in a century which had already witnessed two world wars, the dropping of two atomic bombs, and a Holocaust of unimaginable cruelty and suffering. Beckett could no longer see the world as some kind of moral universe, with some kind of guiding principle behind it. It was bleak and absurd. The same was true for Shakespeare. The Gunpowder Plot had shown Catholics trying to murder the Protestant king, his family, and all of Parliament, so where was the moral universe? And the plague. If the plague could kill thousands and thousands of people – remember that the playhouses had to close in 1605, the year before Lear – where again was there any kind of moral universe?’

Greg talks of the fragility of life and randomness of violence in modern life: ‘The massacres on the Norwegian island, in the Moscow theatre and the Paris Bataclan, or at Columbine and Orlando… well, in Lear, Edmund has the same malignant narcissism as those killers. He believes that shit has been dealt to him – being born a bastard – so it’s justifiable for him to deal shit to others. He tries to destroy his brother, he brings down his father in the process, and he causes the deaths of Goneril and Regan. He’s not obeying any moral principle.’

When Greg relates the stage history of Lear, I’m surprised to learn something new (though it’s perhaps known to fans of one of Alan Bennett’s most famous plays): during the period when King George III was mad – 1811 to 1820 – Lear wasn’t allowed to be performed at all, not even with Nahum Tate’s happy ending. Then three years after the ban, in 1823, Edmund Kean staged it with the original ending. But audiences were so shocked that after just a couple of performances Kean was forced to revert to the Nahum Tate ending again.

Greg finishes with some quotes about the play:

Bernard Shaw spoke of the blasphemous despair of Lear, but added, ‘No man would ever write a better tragedy.’

Jan Kott said Lear was comparable to Bach’s Mass in B minor, Wagner’s Parsifal, Beethoven’s 5th and 9th Symphonies, and Michelangelo’s Last Judgement.

Harold Bloom said that Lear ‘announces the beginning and end of human nature’.

And Donald Wolfit said (when advising an actor about to play Lear), ‘Get a Cordelia you can carry, and watch your Fool!’

As I laugh along with the company, I glance at Natalie Simpson, who’s playing Cordelia. Of course I can’t carry her – in my present condition I couldn’t carry a child.

Handing over to Niki Turner, Greg mentions that the design has sought to achieve something which was said of the Russian film: ‘The power of reality, devoid of everything specific.’

Then Niki does a model-showing, and puts all the costume drawings on the wall. She really has achieved an epic simplicity.

It has a lot of impact, like Greg’s speech. You can feel the excitement in the room.

The RSC’s friendship with China continues. So, joining us for this first week, are three Chinese observers: Li Liuyi, who’ll be directing Lear in Beijing next year; Professor Daniel Yang, who’ll be doing a new Mandarin translation, helped by our own ‘translation’ (i.e. Greg’s practice of getting the whole company to paraphrase Shakespeare English into modern English); and Shihui Weng, who was on the tour, and is now one of the producers of our cross-cultural work with China.

And James Shapiro is here for the week too. To advise and share thoughts from his book 1606. I like him a lot. Tall, lanky, Jewish-blond, a playful spirit and streetwise Brooklyn manner, but a seriously good Shakespeare scholar – one of the best in the world.

He told us all the story of coming through immigration when he flew in yesterday. The officer asked what he did. He replied that he was a Shakespeare professor. She said, ‘Which is your favourite play?’

James said to us, ‘I guess just because I’m working on it at the moment – I’m advising on a production in Shakespeare in the Park – I said, Troilus and Cressida. The woman paused. I suddenly wondered if it had been a trick question. If I answered wrong, would I be refused entry? Then she grinned and said, “Mine is King Lear.”’

He also told us that, earlier this year, this big Bard year, he was interviewed by a journalist, who asked which Shakespeare character was his favourite?

He answered, ‘It’s the First Servant in the Gloucester blinding scene, the guy who challenges his master, Cornwall, who’s doing the blinding. The servant tries to stop him, and indeed wounds him mortally. I love his bravery, his sense of justice.’

Greg remarked, ‘He doesn’t even have a name.’

James laughed. ‘No. Let’s call him Harold. Harold the Avenger!’

‘And we haven’t cast him yet,’ said Greg, looking round the circle of actors. Lots of eager faces looked back – eager to play James Shapiro’s favourite Shakespeare character.

Afternoon. Sitting round a big table, we begin the long, arduous, sometimes boring process of paraphrasing every line of the play. The text is passed on, speech by speech, between the whole company, and the only rule is that you can’t do your own part.

Apart from reading those lines that come my way, I speak up as little as possible. In my head, my voice is a muffled, fuzzy thing. Are the others hearing it like this? Are they thinking – and he’s playing King Lear?

In the tea break, Greg assures me that my voice sounds completely normal. But I can’t help it, I’m feeling demoralised and embarrassed. Back at home, Randall has astonishing news. At today’s family meeting with the specialist – with Yvette present and fully compos mentis – there was a unanimous decision to stop the dialysis treatment, which seems to only have negative results. This is, in effect, a death sentence. The specialist reckons about a month.

How brave of them all, especially Yvette, but how sad.

Ai, the smell of mortality again.

Tuesday 28 June

Woke in the night, thinking: I must find a solution to this hearing thing.

But then, a moment later: I might have to leave this show.

At lunchtime, a taxi took me through the rain to a hospital in Birmingham, to see my ENT man, Mr H. He said that Friday’s tests revealed that there wasn’t enough congestion behind my eardrum to warrant the quick solution, the little incision. But because the situation was urgent, he was prescribing a short but intense course of steroids. Good. They’ve worked for me before, like for the cough in Salesman rehearsals. I like fast, miracle cures. Mr H. had a good bedside manner. Looked me straight in the eyes, smiled, and said, ‘It will get better.’

Back at rehearsals, had an initial fitting with Niki and her Costume Supervisor Ed Parry. The big silver-fox fur coat. It’s going to give me a huge, powerful presence – especially when I stand to curse. But, oddly enough, it presents the same problem as Falstaff’s fat suit. Will my head look too small by comparison? And are we making it even smaller by the number-one skull crop we decided on in Italy? Also, if I’m to wear a radio mic for the storm scenes, I’ll have no hair to hide it in. Maybe in my beard? Or maybe we’ll have to abandon the number-one crop, and rethink the hair-look again?

[See Photo insert]

How fast things can overcome us. If I look back in my diary, just three weeks ago, there was no hint of an ear problem, no sign of trouble. Now suddenly we’re in big trouble. Greg is as spooked by it as I am. Tonight, it exploded:

‘You keep getting ill,’ he said; ‘You just have to change your mental attitude. This is too big a project for you to fuck up!’

Me fucking things up? This isn’t like the two of us talking.

Wednesday 29 June

In rehearsals, paraphrasing away, we discussed the Fool’s advice to Kent in Act Two, Scene Two – ‘Let go thy hold when a great wheel runs down a hill lest it break thy neck with following.’ Someone said, ‘It’s like Jeremy Corbyn’s Shadow Cabinet.’

(Over the last few days, in the wake of the Brexit vote, a lot of Corbyn’s ministers have resigned. He’s not an easy man to warm to, but I’ve found myself pitying him: it’s humiliating to witness.)

In the same scene, the group struggled to interpret Lear’s line about Goneril: ‘She hath tied / Sharp-toothed unkindness, like a vulture, here.’ In the RSC edition, the footnote explains that it’s a reference to the Prometheus legend: he was punished by having his liver gnawed by vultures. James Shapiro added, ‘In Yiddish we say, “She’s eating my kishkas out.”’ (Kishkas = intestines.)

In the coffee break, I asked him if we can have a talk about Lear’s ‘madness’. Over a cuppa in the café, I outlined my latest theory – that it’s more of a nervous breakdown, from which he recovers. James was comfortable with that. Suggested that, as well as talking to psychologists, I should interview some people in retirement. It’s a big part of Lear’s problem, he says, retirement. This is a typically Shapiro angle on Shakespeare: finding the basic, down-to-earth, recognisable demonstrations of human behaviour. Yesterday, he said in rehearsals, ‘I go to newspapers to find out what’s happening in the world; I go to Shakespeare to explain it.’

Of the Lear/Gloucester meeting (Act Four, Scene Five), he said, ‘It is Beckett writing in 1606. I think it’s the greatest scene in all of Shakespeare.’

Back in rehearsals, we were in the storm scenes. Paraphrasing the Fool’s speech – ‘The cod-piece that will house / Before the head has any’ – it was revealed to be all about penises and vaginas. Graham Turner said, ‘Oh dear, we’re not going to workshop this, are we?’ The company roared with laughter. Graham has already won everyone’s heart.

And then on to Lear’s speech about homeless people, ‘Poor naked wretches…’

James said, passionately, ‘No other king in any other play of this period ever talks like this!’

Greg said, ‘I find that speech like a shaft of light in the darkness.’ Then he told the company about his idea of showing vagrants and beggars throughout the first half. He asked Anna (Girvan, assistant director) to recruit some actors and research the subject of dispossessed people in Shakespeare’s time.

(Later, Tony Byrne, who played Worcester and Pistol in the Henries, said to me, ‘That speech – “poor naked wretches” – which is Ciss’s Marxist speech, right? – it’s the complete opposite to Falstaff’s “food for powder” speech, where the lowest in the land only exist as cannon-fodder.’)

In rehearsals, we moved on to Edgar’s entrance disguised as Poor Tom. James explained that Shakespeare borrowed some of Poor Tom’s stream-of-consciouness from Samuel Harsnett’s 1603 book A Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures (about fraudulent exorcisms conducted by Catholic priests). Poor Tom’s description of himself as a ‘wolf in greediness, dog in madness’ is Shakespeare’s version of Harsnett’s ‘the spirit of envy in the similitude of a dog; the spirit of gluttony in the form of a wolf’. And one of the devils that Poor Tom names – Modu – is also Harsnett’s word. It’s plagiarism again, and by Shakespeare himself – I love it!

Greg asked why, when Edgar/Poor Tom hears Gloucester tell Kent that he had a son who planned to murder him, he doesn’t just stand up and say, ‘Look, Dad – it’s me, and it isn’t true’?

I suggested, ‘Because it would spoil the rest of the play.’

But it’s a real problem, and rehearsals are going to have to solve it.

As we were leaving, James said to me, ‘I’m very excited about this production. I have this feeling that Greg and you are going to scale Everest in a way that some recent productions haven’t.’

‘Well, they stopped making it Everest,’ I replied; ‘The chamberpiece productions.’

Grinning, he joined in the game: ‘That’s right, they just helicoptered up to the final camp, and from there the climb to the summit is quite easy.’

Even as I laughed, I had the feeling that I’m going to regret these comments about other productions.

Hearing-wise, the steroids have made a slight improvement, but not enough – yet.

Thursday 30 June

While we tackle a mere play, the real-life dramas in this country beggar belief.

Boris Johnson, who was front-runner as the new Tory leader and PM, has been betrayed by Michael Gove, and has withdrawn from the race.

James Shapiro reveals that Johnson is writing a book about Shakespeare, and had sought his advice. They had a three-hour session together. James tells us, ‘I assumed he knew everything about backstabbing politics, but I guess today’s events show it wasn’t enough.’

I ask James if he’s writing a new book of his own? He’s found such a successful formula – 1599, 1606 – take one year in Shakespeare’s life, and a whole world opens up from it.

He replies, ‘Yeah, but they take me so long to write, they take ten years each. And I can’t use researchers. I figure if you’re gonna swim in the pool, you have to get wet.’

In our paraphrasing rehearsals, we did the blinding scene. James informed us that there were only two legal forms of torture in Shakespeare’s day: the rack, or the strappado (the poor man’s version), where you were hoisted up by your hands, tied behind your back.

(Oich, not a nice thought, and me with a bad arm already.)

And then on to Act Four, Scene Five, which begins with Edgar leading his blind father to what he describes as the edge of a cliff at Dover:

Come on, sir, here’s the place: stand still. How fearful

And dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low!

The crows and choughs that wing the midway air

Show scarce so gross as beetles: halfway down

Hangs one that gathers samphire – dreadful trade! -

Methinks he seems no bigger than his head…

Greg described it as ‘one of Shakespeare’s camera scripts’.

Gloucester jumps off the ‘cliff’ – or rather, just topples over onto flat ground – and then Lear comes on, wearing a crown of flowers, and the famous encounter ensues, between the blind man and the mad king.

This is the scene where Lear is obscene about women. Greg said to the group, ‘I don’t know of another passage in literature which is as full of visceral, misogynist disgust.’

Which led to a discussion about the sexuality in Shakespeare’s writing. James said, ‘It’s very insistent, very titillating for his audience, who don’t have modern-day pornography, but here in the theatre they get very randy love scenes, and boys dressed as girls, and… well, make up your own list. When I teach Shakespeare, I find it very difficult, all the sex – I don’t want the kids thinking of me as a dirty old man, which maybe I am, but that’s not the point. I mean, in Sonnet 116, when he writes of an “ever-fixéd mark” – I call it the “hard-on poem” – yet people read it out at weddings – I sit there blushing!’

As we were finishing, I said to the company, ‘I must tell you that James said to me yesterday that this Dover scene is the greatest scene in all of Shakespeare.’

James laughed, and gestured to the others, ‘Yeah, but I’ve been telling them all the same thing – about their scenes!’

As Greg broke rehearsals, the stage managers gathered round him to get tomorrow’s rehearsal call. He whispered to me, ‘I’d like to do a read-through. Can we?’

I whispered back, ‘No. I need to hear myself read this play. Just give me till Monday. And then, if the steroids haven’t kicked in… then we’ll read it, whatever my hearing’s like. Please.’

Saturday 2 July

Asked Greg if we could sit down and discuss the ear situation, maybe work out some contingency plan.

He agreed, but in a mildly hostile way. His own fear is a factor now.

I suggested I go down to London soon and get a second opinion. He said fine, he could work round that.

As I got up to phone my GP, Greg said, ‘You see, I’m just worried that you’re depressed, clinically depressed. Verne’s death… Yvette slowly dying now… the effect on Randall… and then there’s even Brexit…’

‘Brexit?!’ I said; ‘And then there’s even playing King Lear.’

He looked away. ‘Yup. A lot coming your way at the moment.’

Sunday 3 July

Randall rang. Said everything was very peaceful there. But Yvette was permanently in bed now, and no longer communicating. Randall sat with her for a long time, holding her hand. Josh, their fourteen-year-old grandson, climbed onto the bed and lay next to her. Rabbi Greg came round, and they all surrounded the bed, hands linked. He read out the sonnet we sent (Number 6o: ‘Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore / So do our minutes hasten to their end’), and will do so again at the funeral.

After the call, I went to stand at the fence in the garden, breathing deeply. The sun was half-out, the clouds half-bright, and there was a gentle lifting and lowering of the branches on the big sycamore in the field.

Greg joined me: ‘You all right?’

I answered slowly, ‘In actual fact… I’m extremely well.’

‘Hmn?’

‘Can we please do a read-through tomorrow morning?’

He turned to me in surprise: ‘Yes. Of course we can.’

‘My hearing is better.’

‘I know.’

‘How?’

‘You’ve been so happy all day.’

‘When I woke up this morning, it was gone, just gone. The echo, the fuzziness. I didn’t want to mention it…’

‘Nor did I.’

‘…in case it slipped back. But it hasn’t. It’s completely normal. I suppose the steroids just take a while.’

Greg grinned: ‘How about a G&T?’

‘Absolutely, but just let me do something…’

I went into my studio and emailed my ENT man, Mr H., and my GP, Dr P.: ‘The emergency is over.’

I’ve never been so eager for a read-through in my life. Normally, I dread them: having to present your character in front of the whole company. But this time, the mere fact that I could do it – this was a thing of great joy.

The reading went well. I did well (except for the storm scene – ‘Blow winds’ mustn’t be an aria!), and the whole company did well. Greg has cast them magnificently. So many of the parts are difficult or trap-laden, but we’re blessed by this group, blessed.

Back at home, Greg grinned: ‘I’m afraid we’re going to have to recast Lear.’

‘That’s what I’ve been trying to tell you.’

He hugged me. ‘I was very proud of you. I wish you could’ve seen the younger actors when you were reading – their faces – you raise the bar.’

But the read-through also revealed a problem. The two halves are disproportionate in length: the first lasted about two hours; the second, fifty minutes. Greg has always felt the interval should come after the blinding scene, but now feels he’ll have to make it earlier, after the mock-trial scene, when Lear is being spirited away to Dover, and in some kind of safety. Greg also wants to move the Fool’s strange monologue (‘I’ll speak a prophecy ere I go’) to this point, so that his departure from the play is a purposeful act: in despair, he’s joining the vagrants, who we’ll have seen throughout the first half.

An excellent solution.

At bedtime, I plugged in the phone at the bedside table, in case Randall needs to reach me. I can’t believe we’re going through this again. So soon?

Tuesday 5 July

Morning. We started to stage the first scene, just very roughly – but Greg was already insistent that everyone in the court, whether lords or servants, reacts to whatever enfolds. He called it ‘the amplification of the scene’. Which he explained as: ‘It’s like a blown-up balloon – it only takes one person not to concentrate, and we start losing air.’ The court’s responses need to be as reliable as lines of dialogue, even if different characters express themselves in different ways. So these cues were fixed into Lear’s opening speech today:

‘We have divided / In three our kingdom.’

(Court is surprised.)

‘While we / Unburdened crawl toward death.’

(Court wonders: is this a joke?)

‘The princes, France and Burgundy… here are to be answered.’

(Court applauds.)

Afternoon. Session with Professor Ian Stuart-Hamilton, the psychologist whom the RSC has found to help me put Lear on the couch, and analyse his ‘madness’. He seemed the perfect man for the job. He’s Professor of Developmental Psychology at the University of Glamorgan in Wales, he’s published a book called Introduction to the Psychology of Ageing for Non-Specialists, and he’s a theatre buff, who knows the play well.

Joining us, was my understudy Byron Mondahl (he plays Oswald in the production) – who happens to be South African too, a very warm soul.

Professor Stuart-Hamilton was a large, comfortable man. I liked him immediately when he began by stating: ‘All right, let me say it straightaway – I don’t believe Lear has dementia, full-stop.’

He pointed out that there are two things that demonstrate Lear’s state of mind at the beginning: he’s able to lay out very clear plans for his retirement – ‘planning is not something which a man of decaying intellect can easily do’ – and he’s in rude health: he can go hunting, he can ride through the night from one place to another, he can even run out into a storm.

As for his rash decisions in the first scene, Stuart-Hamilton identified the same syndrome as others have (like Ciss Berry): ‘This man has got whatever he wants all his life. Imagine being a person whom nobody has ever said no to. He’s never had to reason, never had to stop and think. But then suddenly, after his abdication, he can’t get his own way. It’s completely confusing to him.’

I looked up – from jotting notes – ‘So does that cause… what’ll we call it… a kind of nervous breakdown?’

‘I don’t think he has a nervous breakdown. I think he has an episode of delirium. And I think it’s very straightforward to diagnose, physically. He’s an eighty-year-old man. He’s out in a wild storm for a long time. He tears off his outer layer of clothes. He’d almost certainly catch a chill, and this would turn into a fever. It goes into the brain. He begins to hallucinate, he becomes delirious. This lasts on through the Dover scene, when he meets the blind Gloucester. But even then, he’s starting to regain some clarity: ‘I know thee well enough: thy name is Gloucester.’ A line which, I have to tell you, always makes me cry. And then, when Cordelia’s people restrain him, and the doctor tends to him, and makes him rest, he recovers, he returns to sanity. But even then, not without cost. His gentleness in the last few scenes – it’s not bred in his bones. It’s part of his learning curve in the story. And it comes, unfortunately, too late.’

I sat back, astounded. I’d just heard a perfect and completely logical explanation of Lear’s mental journey through the play. And it’s exactly the kind of thing I can respond to: ordinary human behaviour – an old man in cold weather, catching a chill, a fever, starting to hallucinate – transformed by Shakespeare into profound revelations about us all.

So. Not dementia. Delirium.

It’s something I could actively play – delirium – the fever making me shiver and sweat, the hallucinations making me flick my head, trying to clear my vision.

I thanked the professor profusely.

‘Pressure is a privilege.’

Greg likes to quote this – it was said by the tennis champion, Serena Williams – and he needs to keep reminding himself of it in his job. Like this afternoon, when he had to leave rehearsals early to dash down to London. It was for an event at 10 Downing Street: their contribution to the big Shakespeare year. Held in the garden there, it was organised by the RSC Education Department, and consisted of a selection of Shakespeare extracts performed by a mixture of RSC actors and schoolchildren. David Cameron, shortly due to move home from this famous address, made a Shakespeare-styled speech, in which he wondered whether the future (i.e. post-Brexit) would hold a ‘brave new world’ or a ‘winter of discontent’?

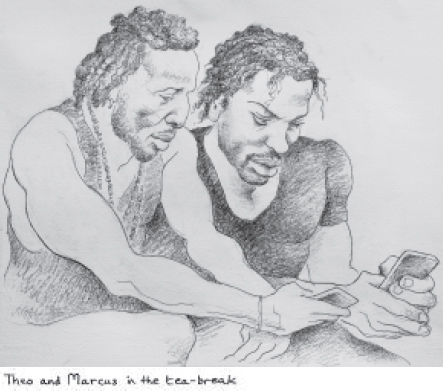

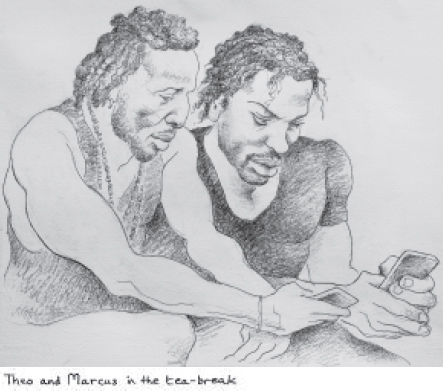

We’ve got two giants in our cast. Marcus Griffiths and Theo Ogundipe. Both tall and strongly built. Fine actors too. Marcus is a formidable Laertes in Hamlet; and a few years ago, in Greg’s African Julius Caesar, Theo played the Soothsayer as a sangoma in direct contact with the spirit world – when he said ‘Beware the Ides of March’, you better believe it! In Lear, Marcus is France and Theo is Burgundy, and then they play a series of smaller roles. But they bring such power to these – just as we roughly stage some scenes – they prove what I said the other day: we’re blessed with this company of actors.

Later. Evening. I’d never say this aloud, and hesitate even to write it down, but the hearing problem is coming back. Not as fuzzy as before, but the echo is there again. The steroids must’ve only provided a temporary cure. But at least it allowed me to do the read-through – and gave me a big boost psychologically. Now I’m just going to have to do what sportsmen do, when they talk of ‘playing on an injury’.

Thursday 7 July

When I walk into the rehearsal room this morning, I find one wall transformed. Covered with sheets of paper: some with images, some with text. It’s the research that Anna has led, about the homeless in Shakespeare’s time. Much of it is from two books by Gamini Salgado: The Elizabethan Underworld and Cony-catchers and Bawdy Baskets.

Reading the extracts, I learn that the failure of harvests in the 1590s, and subsequent shortage of food, led to the Enclosure Acts, where people were thrown off common land and deprived of their livelihoods. Some turned to petty crime, while others took to roaming the countryside.

This is the population that Greg wants to represent, as a kind of chorus, in the production.

I go over to my bag, find a picture, and stick it up among the others on the wall. It’s the one of Prince Philip which I sketched about a year ago – showing him in some kind of discomfort during an official ceremony.

Good. Now the display shows both sides of the world we’re trying to create. The poor naked wretches and the burden of monarchy.

Oddly, both sides represent the Dispossessed.

Odder still, Lear has brought it on himself.

In rehearsals of the storm scenes, I confessed that I didn’t know what to do with ‘Blow winds’. I said, ‘Let’s take the reality. A man is shouting in a storm. You wouldn’t be able to hear him. He probably wouldn’t be able to hear himself…’

(Hear himself… was I talking about Lear or me?)

‘…We’ve solved how to do it in performance – we’ll be using mics – but how do we rehearse? I can’t just stand here, yelling. I’ll strain my voice.’

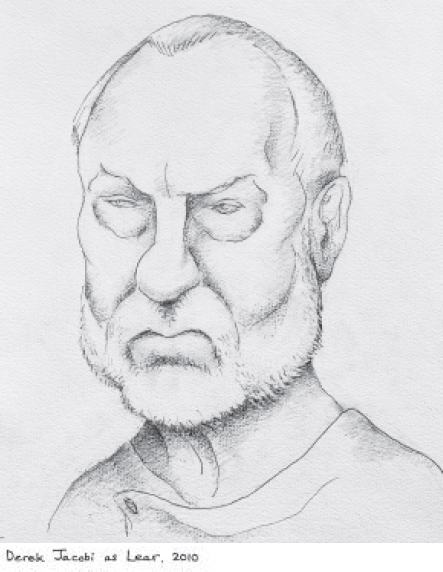

I mentioned the brilliant solution which Michael Grandage and Derek Jacobi found in their 2010 Donmar production. When you first saw Lear in the storm, you heard the full cacophony of it. But as he lifted his head to speak, all the sound was abruptly cut, and he whispered the speech: ‘Blow winds…’ It was, as Lear describes in his next scene, ‘The tempest in my mind’.

‘Couldn’t we borrow that?’ I suggested tentatively.

‘Absolutely not,’ said Greg; ‘Much too recent. And anyway, that was a chamber-piece production and that was a chamber-piece solution, and we’re not doing a chamber-piece.’

He then came up with his own, striking scenario for the scene. He suggested that maybe the winds aren’t blowing – yet – and the speech is a desperate plea (‘Blow winds, I beg you!’), not simply a description of what’s already happening (‘Yeah, go on winds, blow!’)…

… And so we created a narrative to the speech:

• A subsidence in the storm prompts, ‘Blow winds…’

• A flash of lightning prompts, ‘You sulphurous and thoughtexecuting fires…’

• A crash of thunder prompts, ‘And thou, all-shaking thunder…’

We can put these cues into rehearsals, we can create the other character in the scene – the storm – for me to play against.

Stage management made precise notes: they’ll find some recordings from stock (for now) to play when we next rehearse the scene.

For me this was, potentially, a solution to the hardest part of the role.

Then we moved onto the first Poor Tom scene. Oliver Johnstone really went for the mad tumble of language in his speeches. (It’s not just Beckett who owes a debt to Shakespeare, it’s James Joyce too.) I was also intrigued to note that Olly had a new range of movements – some of them twisted and jerky, almost like cerebral palsy – and new sounds too: mumblings and stutters. This was all from his ‘secret’ rehearsals with Greg. Which is a technique Greg used with the witches in Macbeth. He’d work with them privately, so that we, the rest of the cast, never knew what they were thinking or what motivated them. It made them more mysterious, more powerful.

I think, in fact, it’s originally a Mike Leigh method. I experienced it when I did his stage play Goose-Pimples (1980, Hampstead and Garrick). Each of the characters was developed separately, in one-to-ones with Mike, so that when he started to bring us together and create a storyline, we encountered one another as strangers. After all, in real life you know little or nothing about people you meet for the first time.

I remember that the long Goose-Pimples improvisations, and later the equally long Auschwitz exercises that Richard Wilson devised to rehearse Primo (2004, National Theatre and Broadway) can make your head go to a very funny place. I was angry with both Mike and Richard after the sessions – because of where they’d taken me – yet my anger was totally unjustified: I could’ve stopped at any point, and walked away. Except I couldn’t, really – it becomes a kind of selfhypnosis.

Today, I wondered how much Edgar loses himself in the Poor Tom disguise? But, of course, I wasn’t allowed to ask.

Olly had a question for me though, in the mock-trial scene: had Lear been planning this cross-examination for a while, ever since his daughters turned against him after the abdication?

‘That’s an interesting thought,’ I said; ‘There must’ve been people yesterday…’ (when the Chilcot Inquiry into the Iraq War was published) ‘…who’ve become obsessed with the idea that Tony Blair should be put on trial for… what’s it called?… humanity… what’s the phrase?’

Someone suggested, ‘Crimes against humanity?’

‘Exactly!’ I cried; ‘That’s what Lear has been obsessing about. Except in his case, it’s crimes against the king!’

Leaving rehearsals, Greg and I happened to bump into Jonathan Ruddick, our sound designer, and discussed what the storm should be like. Jonno is a fellow South African, so he knew exactly what we meant when we talked about the electrical storms you get on Joburg afternoons: dark, hot, tremendously violent affairs, with hailstones the size of ice cubes, alarming sheets of lightning, and thunderclaps that sound like they’ve rolled across all of Africa.

Friday 8 July

Wasn’t called till noon. So went through all the lines, the whole part. An increasingly dull exercise, made worse by my hearing condition – which I now call Lear’s Ear – being bad again. These lines, these bloody lines, which I’ve been learning since God knows when (Salesman?), echoing, banging, slowly round my fucking skull.

In rehearsals, Lear’s Ear got worse. And it was the Dover scene. Which James Shapiro called the greatest scene in Shakespeare. But which today, in my trapped head, sounded like just generalised madness, useless stuff.

(I certainly made no further mention of wearing either a red nose or a tomato-nose in the scene!)

In the car home, I said to Greg: ‘Y’know, we’re going to have to sort out this ear thing. If we don’t, it’s going to hit us hard when the pressure’s really on. Final run-throughs, first previews…’

Greg said nothing, just stared ahead grimly. He thought the problem was solved. (Me too.) He can’t believe it isn’t. (Me neither.)

But at home, everything changed again. A call from Randall:

‘Well, it’s all done. At about 11.30 this morning… I was in the living room… I thought, “I must give Mida a break.” As I got to the door of the bedroom, Mida held up her hand – it’s happening. By the time I reached the bed, Yvette was gone. Looking very calm.’

By now, the whole family was there, supporting one another.

We lit a candle for Yvette. There were no more of those yahrzeit candles left, so we just used a night-light. It didn’t matter – I don’t know what the real Jewish ritual is anyway, but we do our version, and it’s comforting.

Saturday 9 July

Slept badly – in fact, hardly slept at all. Some of the night, sat by the night-light – it was in the big window, with big blackness outside. Thought back over the last year. Uncanny. It’s been dominated by preparations for Lear, and characterised by Lear-like obsessions: physical weakness (ailments) and the smell of mortality (death). Real life has certainly provided plentiful research material for playing Lear, but it hasn’t felt useful. Just too close for comfort.

Today was like a déjà vu of last weekend: me trying to email various doctors.

I invited Greg to read my email to my GP, Dr P., before I sent it: to check that he agreed with my assessment of the situation.

It began: ‘Either we find a cure or I’ll have to leave the show.’

Greg stood up sharply. He said, ‘I’ve never understood it in those terms.’

(Correct. I’ve never said the words aloud to him.)

He walked out of the room.

Then came back and asked for a talk.

Said: ‘This is very hard for me. I’m in three different positions here. Your partner. The director of the show. The Artistic Director of the company. If you do have to leave… I don’t know which of me goes into action. I think I may have to talk to Catherine and ask for help…’ (Catherine Mallyon, the Executive Director.) ‘…I’m in an impossible situation. The private and professional relationships have got impossibly entangled. What do we do?’

We sat in silence.

Then he mentioned that Michael Pennington was currently touring Lear round the country.

‘So… he knows the lines?’ I asked slowly.

‘He knows the lines, yes.’

(In 1999, when Greg was doing Timon of Athens with Alan Bates, and Bates had to withdraw for health reasons, it was Pennington who stepped in at the last moment, heroically saving the day.)

Greg continued: ‘Anyway, it would be an insult to ask him. He’s a great actor, a seriously great actor. And he’s angry with me. He wanted me to bring the Lear that he did in Brooklyn, at Theatre for a New Audience, to Stratford. But I wouldn’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because I thought the RSC was doing it with you!’

We stared at one another bleakly. A kind of disbelief. Was this happening? After years and years of preparation, was this really happening?

And if I did leave, what would I do? Where would I go? I couldn’t stay here, in Stratford, while they rehearsed and opened. So – Islington, I suppose. But what would I do? Curl up in a corner…?

Dr P. rang. (Having received my email.) Unfortunately, his favoured ENT man is on holiday, but he’ll find someone else. For some time next week. Which puts all our decisions on hold for now.

Spoke to Randall. He was peaceful, but said things felt odd. I said that we’d be thinking of them during the funeral on Monday. My voice was breaking up, but Randall ignored it kindly, taking on his role as older brother: ‘I know – I feel your strength.’

So our lives continue: half-crazy, half-normal.

Down to London for Richard Wilson’s eightieth birthday party.

Arrived at our Islington home in time to watch the last hour of the Wimbledon men’s final. When Andy Murray won, his demeanour was fascinating. No apparent joy, no great elation. Just a rather blank look of exhaustion and relief. He had attempted a mighty feat, achieved it, and now it was over. Reminded me of press nights.

Richard’s party was at the Wallace Collection at Hertford House in Manchester Square, Marylebone: a grand art gallery which is hired out for private functions. Richard’s seventy-fifth was held here too, in 2011. On that occasion I found myself chatting to two Lears: Ian McKellen, who played it in 2007, a massive production on the RSC main stage, and then a world tour, and Jonathan Pryce, who was about to play it the following year, 2012.

‘Where?’ asked Ian.

‘The Almeida,’ Jonathan replied.

‘Oh, easy!’ said Ian; ‘You can’t fail in a small space.’

I saw Jonathan frown. We changed the subject.

Tonight, I was with the two of them again. I said, ‘I can’t believe that I’m up against, of all people, Glenda Jackson!’

‘And me,’ said Ian briskly.

I was intrigued. I knew Ian hadn’t been happy in his previous production.

I asked, ‘When? Where?’

‘Next year,’ he replied; ‘Chichester, in the Minerva, the studio.’

I glanced at Jonathan: he chose not to say, ‘Oh, easy!’

Ian continued, ‘Well, it is a domestic tragedy, after all.’

I changed the subject.

Greg and I saw Jonathan play it at the Almeida. And, despite the confined space, he gave a fine performance: not just his trademark danger, but real, painful depths. I was very moved by my former Liverpool Everyman colleague.

Stratford.

This week we’re putting the whole play on its feet, doing ‘the big sketch’ as Greg likes to call it. This is the moment when he discovers if his instincts about the production, forged over months of thought, discussion and meetings, are proving sound and true. In a way, rehearsals are simply the test drives of a vehicle that has been built beforehand. You can make adjustments or even major changes, but the basic structure already exists.

(I wish this wasn’t the case. I wish the whole company – the director, the designer, the composer, and all the actors – could collaborate from the beginning. But that’s not possible – on a major production of a major classical play. Not in this country, at any rate. Arts funding in Europe allows for months and months of rehearsals. Here we’re lucky if we get six weeks.)

Greg used today’s big sketch to put groups of homeless people into the action. They’ll be crouched around the stage as the audience arrive, and then shooed away when the court enters… At Goneril’s home, they’ll be gathered at the back door, for a distribution of leftover food… When Edgar is chased through the night by guards, they’ll be seen darting away, keeping out of trouble… And they’ll be in the storm…

I felt excited by the work, and tried to ignore an onset of Lear’s Ear.

(My appointment with the second-opinion ENT man is booked for Wednesday.)

Rang Randall, and heard about today’s funeral. It was very emotional, he said, but good. Apparently, Rabbi Greg read our sonnet so well that Randall suggested a season at the RSC.

Tonight a hedgehog came into our garden. In the half-dark, it looked like a strange, squiggly little thing. Greg whispered to me, ‘It’s so rare to see them – when I was growing up in Lancashire, they were everywhere – but now any sighting is like a little blessing.’ He crawled out with the camera and a saucer of water. He gets such joy from things like this. I love him for that joy.

Rehearsed the stocks scene (Act Two, Scene Two).

The other day, Professor Stuart-Hamilton mentioned ‘elder-speak’ (the equivalent of ‘baby-talk’), which staff in old-age homes are forbidden to use. But today that’s exactly how Kelly Williams (Regan) was addressing Lear, and it worked perfectly. ‘O sir, you are old,’ she cooed at me in a kindly tone; ‘Nature in you stands on the very verge / Of her confine.’ I don’t know how, but she managed to make this insult sound sympathetic. It was very subtle, very clever. It allowed Lear to be fooled and ambushed by Regan in a way that he never is with Goneril.

And indeed, when Goneril entered the scene now – Nia Gwynne – the tension immediately rose. Then I suddenly became tender with her, on the line, ‘But yet thou art my flesh, my blood, my daughter.’ We both fumbled into an embrace – it’s not something this father and child ever do. Though not for long. Lear’s bile spilled out again: ‘Or rather a disease that’s in my flesh / Which I must needs call mine: thou art a boil / A plague sore…!’ By now the embrace had turned into me holding her in a vice-like grip, from which she was fighting to free herself. (I hadn’t planned to do any of this, so hadn’t warned her, and yet she simply went with the idea – her acting instincts are fantastic.)

The moment was an example of what Greg calls ‘crossroads’. Where things may go a different way, even in these overfamiliar plays, these stories which we think we know inside out. What if Lear and Goneril reconciled? Pursuing these crossroad moments is one of Greg’s strongest insights as a Shakespeare director, because they enliven and endanger the action. They reveal the choices which your character has. They allow you to be truly in the moment, without knowing what the next one holds.

Afterwards, sitting in the break-out room, where actors wait between scenes, Nia and I discussed the Lear/Goneril relationship. Why is it so toxic? They can’t seem to lay eyes on one another without breaking into a row. And the language that Lear uses to her…! Not just the ‘disease, boil, plague sore’ rant, but his curse on her womb. It’s ugly stuff. The only other time in the play that Lear speaks like this is his obscene description of female genitalia. What is the connection between his basic misogyny and Goneril in particular?

Nia thought for a moment, then said, ‘Well, it’s probably quite simple, isn’t it?’

‘Which is what?’

‘She wasn’t born a boy…’

I sat forward. ‘Of course!’

‘…His eldest child – he needed it to be a boy.’

Later, I said to Greg, ‘D’you think… to really understand Lear… you need to have kids?’

He said, ‘Is this another proposal? Like with our marriage.’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘I don’t think it’s a factor, no. Any more than it is for the actor who plays Macbeth to have committed a murder. In Lear, I think the family feel is important, that visceral feel – how love can turn to hate and back again in a flash – but we all know that.’

Graham Turner and I did some preliminary tests on the little platform which will lift us into mid-air for ‘Blow winds’ – quite high, on a level with the circle. We’ll be wearing security belts, with lanyards attached, and it’s up to Graham to clip these to the floor.

He said, ‘So is it the same principle as the safety instructions on a plane – put on your own oxygen mask before helping anyone else?’

‘No, it’s opposite,’ said George (Hims, deputy stage manager); ‘Tony’s standing, Graham’s kneeling, so Graham has to attach Tony before he attaches himself.’

I said to Graham, ‘Looks like I’m going to have to buy you lots of drinks during this run.’

Everyone laughed, but I think this is going to be quite a scary stunt.

Wednesday 13 July

Long day. Down to London and back, to get a second opinion from the ENT specialist, Professor W. He was very thorough, and explained everything carefully, using pictures and models of the ear. Did more hearing tests and an MRI scan. Thought there might be something wrong with the mixture of fluid in my inner, inner ear: the coiled, shell-like bit. Prescribed some sodium-type tablets, and promised to report fully to both Dr P. and me.

Back in Stratford, the TV news shows the real world in farce: the UKIP leader Nigel Farage has resigned (mind you, was he ever of the real world?), while at Number 10, David Cameron has moved out, and Theresa May in. And even Boris Johnson has bounced back – he’s the new Foreign Secretary. But he’s a clown, who isn’t respected abroad. You couldn’t make it up.

Thursday 14 July

Because I missed rehearsals yesterday, all my middle scenes were scheduled today.

Fruitful discovery in the hovel scene. The moment Poor Tom appears, Lear seems to lose interest in the Fool. It’s like Poor Tom replaces the Fool, becoming Lear’s new confidant, a new font of wisdom, or, in Lear’s own words, ‘my philosopher’. As the old man slips into his delusional state, the Fool’s gags and ditties no longer provide enough stimulation; Poor Tom’s surrealist visions make for much headier stuff. Rehearsing the sequence, I tried focusing on Poor Tom intently, obsessively, and being increasingly aggressive towards the Fool, turning my back when he spoke, or shoving him away. (All of which could also, of course, contribute to the Fool’s exit from the play.)

When we staged the mock-trial, Greg experimented with putting vagrants into this scene as well. They’re sheltering from the storm in a barn or outhouse when Lear’s group suddenly arrives, and then they become a bemused audience to the crazy court case that ensues. We found it worked well if Lear actually used some of them as the accused – Goneril and Regan – and even as his pet dogs, Trey, Blanch and Sweetheart.

The actors’ instincts were to run away from me whenever I dragged them into the spotlight, but no matter. I continued to see them where they had been. They were swimming in and out of focus – the hallucinations which Professor Stuart-Hamilton talked about last week.

This led to me half-collapsing. Then, when Gloucester said, ‘I have o’erheard a plot of death upon him’, he and Kent put me onto a little wooden cart, to spirit me away to Dover.

The rehearsal was clearly yielding results – everyone could feel Lear losing his grip.

But never mind the royal old loony, I needed to be on the psychiatrist’s couch today. On Tuesday I was working at full pelt, but today Lear’s Ear was so bad it was like being disabled again. My spirits go up and down with this fucking thing! This is the strangest rehearsal period of my life.

However, there was a moment this afternoon…

In between scenes, I was pacing around, preoccupied with my own troubles, when I walked through the break-out room, and found it full of actors learning lines. A particular atmosphere. Almost as still as a library, except for discreet whispering coming from every side, nobody wanting to disturb their neighbour. They were practising their understudy lines: as well as playing their own roles, most of them will also understudy one of the principals. At the centre of them all was Byron Mondahl – in the show, he’s a very original Oswald, stocky and brutish, but now he was learning Lear. I don’t think people have any clue how much work goes into this process, and it’s boring, repetitive work, it’s swotting for school exams. But there’s no easy way round, because any one of them might have to go on for real – at a moment’s notice. And there will also be an understudy performance, open to the public, when they’ll do the whole play, and there’ll be no scripts allowed, no prompts.

Looking round the room today, with them all deeply focused – it was like they were in a choir, singing, or rather, mouthing different tunes – it struck me that, unless I get my act together, these people are going to be thrown into a lot of chaos, and a lot of their hard work could be wasted.

Feeling humbled, I went back into rehearsals. And discovered there is a plus side to my present condition: Lear’s character is becoming angrier than ever – both he and I are very trapped, very reckless.

Friday 15 July

A good day.

Working on the Dover scene, there was a moment when Greg’s face lit up with excitement – as if he was reading the text for the first time.

‘Lear’s supposed to be mad at this stage,’ he said; ‘Yet look at these lines when he’s talking about his courtiers…’ He pointed to the text:

LEAR: To say ‘Ay’ and ‘No’ to everything that I said ‘Ay’ and ‘No’ to was no good divinity.

And then:

LEAR: They told me I was everything:’tis a lie.

Greg laughed. ‘That’s not madness talking, that’s sanity! Madness was when he was living as a demi-god. Now, in this scene, we’re starting to realise how much Lear has learned.’

We also had an excellent session with Natalie Simpson – on the Lear/Cordelia relationship. Previously, we’ve already decided there were probably two Mrs Lears, which at least explains the gap between the pair of older daughters and the younger one. But the interaction of Lear and Cordelia remains very complicated. They have the first scene when Cordelia refuses to play along with Lear’s game – Who loves me most? – and all hell breaks loose. Then they don’t see one another for the next three acts (about two hours in playing time), and then, after their reunion, there has to be great tenderness. Natalie can do this effortlessly – real tears, real laughter – which makes it effortless for me too. I keep remembering James Shapiro saying that it’s what Lear really wanted for his retirement: just to be with Cordelia. In fact, Lear actually states it at the beginning: ‘I loved her most, and thought to set my rest / On her kind nursery.’ So now, at the end, when they’re sent to prison together, it holds a curious joy for him: ‘We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage.’

But not for long, unfortunately.

Given that I can’t carry Cordelia onstage for ‘Howl, howl, howl’, Greg has devised something else which could still deliver an iconic image.

I’ll be sitting on the little wooden cart – which took me to Dover – with Cordelia’s dead body in my arms.

A kind of Pietà.

A mirror of Lear’s spectacular first entrance, but in broken form.

On the evening TV news, watched a report on the terrorist massacre in Nice last night. The brutality of mowing down that number of people with a truck.

And people say Lear is too violent.

Four weeks of rehearsals left.

The weather’s turned: the heat today is intense.

Dr P. has received Professor W.’s second-opinion report. We speak on the phone. Dr P. proceeds delicately:

‘He says there’s nothing really wrong with your hearing. He wondered if it was… anxiety… about the role.’

I go silent.

(My mind flicks back to an exchange with Professor W. last Wednesday. He said to me, ‘Presumably you’ve played Lear before?’ I gave a small laugh: ‘Good God, no – you wait a lifetime to play Lear.’)

Dr P. continues: ‘I told him you were a seasoned professional. You’re not anxious about it, are you?’

‘Well, I suppose… well, yes… in a way… an appropriate way… you don’t do these things lightly. I mean, Andy Murray couldn’t have gone out to play the final without some anxiety. He wouldn’t be a living, breathing human being if he did. But then professionalism kicks in, and…’

I trail off.

Dr P. suggests I continue taking the sodium tablets. We discuss a few more things, and finish the call.

I put down the phone. In a strange state: shock and anger.

Anxiety…?!

People really don’t understand what it’s like.

My point about Andy Murray was very good.

Of course there’s anxiety!

But on the other hand, Andy Murray doesn’t develop a mysterious illness that threatens to stop him playing altogether.

So… Professor W. thinks it’s anxiety… psychosomatic… (a potent topic in the light of Yvette’s life…)

Greg said something similar a couple of weeks ago: ‘You just have to change your mental attitude.’

Psychosomatic. Such a difficult thing to work out. I mean, insomnia – is that psychosomatic? What else can it be? It’s only you preventing you from sleeping. Yet there’s something respectable about the word ‘insomniac’ and something disgraceful about ‘psychosomatic’, something unbalanced…

…Does it mean that Lear isn’t the only mad one around here? Joining Greg for supper, I just gave a vague account of the phone call, without mentioning Professor W.’s theory. Then I ate in silence. I felt confused, unsure what to do with this new information, or even if it was information. I mean, who says it’s true? I’ve put so much preparation and passion into this, why would I deliberately (if subconsciously) sabotage myself? It makes no sense. Or does it? I have had struggles with work before – which I’ve written about openly – like stage fright. And I’ve done some projects that have felt like mistakes, and that I’ve considered leaving. I actually did leave one (Cleo, Camping, Emmanuelle and Dick at the National), which I’m not proud about. But I can honestly say that, until the deafness made the job seem undoable, I nursed no secret desire to escape Lear. So no, it doesn’t make any sense at all.

After our meal, Greg suddenly produced one of his perfectly timed surprises: a DVD of The Producers – the film of the musical. For two hours, we roared with laughter.

Now that was what the doctor ordered.

Tuesday 19 July

This morning there was productive work on what we call the busstop scene (Act One, Scene Five).

Greg never countenanced me and Graham doing it like Gambon and I had – as a front-cloth scene – but I think it’s retained some small element of that. While the knights saddle the horses, I’m sitting on a stack of our luggage, very troubled. Graham bravely sits right next to me. Starts telling jokes. I don’t respond. But then he breaks my resolve (he knows me so well) and I chuckle. Now we go back and forth, him sometimes making me laugh, me sometimes lost in dark thoughts. At the end I implore him: ‘Let me not be mad… keep me in temper.’ Which means, keep up the jokes.

(Like: keep showing me The Producers.)

We also worked on the storm, with there being more story in the chaos.

Despite my muffled hearing, I sensed that my voice had power. At the end of the day, Kate (Godfrey, Head of Voice) complimented me on it.

Today was the hottest day of the year. At the theatre, the airconditioning broke down, and they had to cancel the Hamlet performance. A pity. The show is sold out, so tonight’s audience got their money back, but not another chance to see it.

Wednesday 20 July

Costume fitting. At first, the fur coat makes Lear super-huge… then he slowly diminishes… just the tunic for the storm… just underclothes for the rest… the audience will watch him go from giant god to little man.

Niki and Sandra (Smith, Head of Wigs) liked the sketch I did in Italy, of the cropped-hair look. Today, we created an impression of it by me wearing a tight stocking on my head – and it didn’t seem disproportionately small against the big coat. Maybe we can still use it…

Spoke to Randall. Said he keeps thinking, ‘Must ask Yvette about so-and-so’ and then realises he can’t. It’s making him jumpy. Well, of course – they were married for fifty years. And he’s unsettled by not being able to sell the house immediately and move to a flat. The ones he’s looked at are all very small. And they have to be pet-friendly – his beloved dog, Duke – which rules out about ninety per cent of them.

Friday 22 July

Cymbeline returned to the repertoire today, after five weeks off, so a lot of the Lear cast were involved in line-runs, etc.

But Greg and I had a good solus session.

In the scenes after Lear’s abdication, we noted his confusion as things start to go wrong. It’s the confusion of royalty trying to figure out the ordinary world. How little he says during Goneril’s long tirade in the post-hunt dinner scene. He can’t believe it’s happening, that she’s talking to him like this, and in public.

Slow confusion is so much more interesting than instant tantrum.

I think it’s a significant breakthrough.

I’ve been falling into a familiar Shakespeare trap. There’s so much flair and swagger to the writing – like Lear’s rages – that you can just be swept away on high by it, rather than dig deeper.

A perfect example is the ‘O, reason not the need’ speech. It’s so famous, you assume you know what it means, but it’s actually quite complex. Today we inched our way through it, line by line:

‘O, reason not the need’

(Don’t question what is absolutely necessary.)

‘Our basest beggars / Are in the poorest thing superfluous’

(Even the poorest beggars own something, however meagre, which is more than they essentially need.)

‘Allow not nature more than nature needs, / Man’s life is cheap as beast’s.’

(If you don’t acknowledge individual requirements and yearnings, people are like animals.)

…And so on we went.

On the TV news, another massacre – in Munich. This thing is on a terrible roll. I’m glad we’re not in London at the moment. Mind you, Stratford, in this special year, would make a prime target, a major story. ISIS isn’t squeamish about attacking cultural targets – their own, especially – but maybe they just don’t know about Shakespeare.

Later. We sat in the garden, watching the amazingly fast ascent of an enormous, blood-red moon through the trees at the far end of the field. I’ve not been mentioning Lear’s Ear, knowing it alarms Greg, but now he invited me to discuss it.

I said, ‘I don’t know what to think about it, say about it, any more.’

Then I finally told him about Professor W.’s theory – that it was possibly just anxiety.

He was sympathetic: ‘You’ve been through a lot – two deaths in the family – that’s a lot.’ Suggested I speak to my former psychotherapist, Marietta Young, maybe on Skype.

Monday 25 July

Thank God, it proved very simple and quick to arrange a session with Marietta – not on Skype, but by phone – and we did it at 6.15 p.m. this evening.

(I met Marietta when I was in a clinic for cocaine dependency in 1996. Her expertise was art therapy. For obvious reasons, we clicked. I continued to see her for many years after the clinic, and only stopped quite recently.)

It was good hearing her voice again now, wise and humorous, with its faint trace of her Czechoslovakian roots.

I gave her a quick outline of the hearing condition. Then:

‘…But this new specialist, he thinks it may just be anxiety.’

‘And how do you feel about that?’ Marietta asked carefully.

I took a long time to answer. ‘To be honest… totally honest… it has occurred to me too.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s not the first time that my body’s tried to help me out when my mind is under pressure.’

‘When was it before?’

‘Well, I’m sure I’ve told you in the past…’

‘Tell me again.’

I felt embarrassed, but kept going:

‘My bar mitzvah…’

(Even as I started the familiar old story, I felt I was in a Woody Allen script.)

At your bar mitzvah, you have to sing a portion of the Torah, but I’m tone-deaf… So for a year, in 1962, aged twelve, I was humiliated by a sadistic teacher, Bitnoen, in front of a class of sniggering boys… On the weekend before my big day, Bitnoen came round to our house, to tell my parents it was no good, I’d just have to speak the portion… Two mythic figures, the Bar Mitzvah Teacher and the Jewish Mother locked horns, and guess who won?… I would sing!… During the days before the event, I became ill, a kind of flu… Then I managed to stagger through the ceremony, and afterwards, people said, ‘He did well, considering.’

I told Marietta that over the last few weeks, whenever I’ve passed my big autobiographical painting, The Audience, which hangs in our Stratford house, I’ve found myself stopping, to glare at the portrait of Bitnoen – bloated, toad-like – looming over the portrait of me as a teenager, hunched and ashamed, wearing my little bar mitzvah suit, with yarmulke and tallis. ‘I want to hit Bitnoen,’ I say to Marietta; ‘Stab him, vandalise the painting.’

Then we had one of those exhilarating sessions of old, where we become like a pair of sleuths solving a mystery.

At his bar mitzvah, a boy comes of age; it’s his passage into manhood.

When an actor plays Lear, it’s another coming-of-age.

At my bar mitzvah, my (singing) voice wasn’t up to it.

With Lear, my private fear has been that my (speaking) voice wasn’t up to it either.

Marietta suggested I try and use all my current problems, and put them into the work itself.

Use my anxiety. Lear has anxieties too.

Use my deafness. Lear has failing powers too.

Lear is a strong character, but operating inside a crumbling old body.

I’m a strong actor, but with some infirmities.

We finished the phone call by giving my condition a new nickname, something that I could mock and dismiss it with – no longer Lear’s Ear, now FAKE DEAFNESS.

After the call, I went into Greg’s study.

‘How was it?’ he asked.

I nodded: ‘Yup, she’s pretty good, Marietta.’

[See Photo insert]

Tuesday 26 July

On waking…

Will my hearing be completely normal? (Because of the call with Marietta.)

Yes!

No.

In fact, in rehearsals – of Act One, Scene One, ‘Division of the Kingdom’ – I had one of my worst days ever. My deafness was deafening. It was like something out of The Exorcist. The demon had been ruthlessly exposed, and was saying, ‘Right, now let me show you what I can really do!’ But I felt relaxed. I was just stuck with it, this FAKE DEAFNESS. It’s amazing what we can inflict on ourselves – what thing is sitting in my brain, closing or opening valves in my ears? – and amazing how we can get used to them. Like with my bad arm, I’m learning to live with my erratic hearing. I mean, in today’s rehearsal, I knew my voice was soaring out of my deafness, and felt encouraged.

So – I’ve turned the corner.

In the play, Lear has his delusional phase. In real life, I’ve had mine. And it’s over.

I’m not leaving this production. There’ll be no further thought or talk of that – which I told Greg this evening. We have three weeks of rehearsals left. I’m not wasting any more time dwelling on my hearing. I’ve just got to go for this.